Super Resolution

Super Resolution is an image processing technique that enhances/restores a low-resolution image to a higher resolution. Researchers have proposed and implemented many methods of tackling this classical computer vision task over the years, and improvements have been rapid in the last decade with the boom in deep learning. However, one of the major pitfalls of both CNN and standard transformer-based models is an inability to capture a wide range of spatial information from the input image. We will look at the design and architecture of one of the current cutting-edge models, HAT, which combats this problem by utilizing channel attention, self-attention, and cross-attention. Then we will apply the HAT model to novel input images to test its performance.

Introduction

Single Image Super-Resolution (SISR) is a fundamental low-level problem in computer vision and image processing that aims to reconstruct high-resolution images from their low-resolution counterparts. This problem has wide-ranging applications in a variety of distinct fields such as medical imaging, security surveillance, satellite image analysis, and computer graphics. Although the problem has been studied for decades, it has not been until recently that models have reached a level of performance that allows it to be widely used. The difficulty with earlier attempts lay in the difference between the simplistic classical model of image degradation that these models relied on and the much more complex degradation of real-world images.

The classical model of degradation is written as

\[\textbf{y} = (\textbf{x} \otimes \textbf{k}) \downarrow_{s} + \textbf{n}\]where the high-resolution image \(\textbf{x}\) is convoluted by the blur kernel \(\textbf{k}\), the output of this convolution is downsampled by a factor of \(\text{s}\) (for every s x s patch in the image, one pixel is kept), and finally the white Gaussian noise \(\textbf{n}\) is added.

While this model is succinct, the mechanics of image degradation in reality are much more complicated. Thus, it was not until the advent of deep learning methods, in particular, the CNN and then the transformer, that significant progress was made. In the rest of this paper, we will focus on the incremental improvement of these deep learning models, utilizing the PSNR and SSIM metrics for comparison. PSNR, which stands for peak signal-to-noise ratio is a very commonly used metric that compares the pixel values of the reference image to the degraded image using MSE. It is measured in decibels. SSIM (structural similarity index measure) is another metric that compares a reference image and a degraded image, measured from 0 to 1. Its difference from PSNR lies in the fact that instead of just measuring the absolute error, it measures the structural similarity, taking into account factors such as luminance and structure.

We will start with the introduction of SRCNN, the early convolutional neural network for this task. More recently, transformers have gained attention in SISR for their ability to model long-range dependencies. Of the recent transformer-based models, we will discuss SwinIR, which utilizes the Swin transformer architecture. Then we will conclude with an in-depth look at the focus of our paper, HAT, which improves the ability of sliding window transformers to perform cross-window information interaction, thus achieving state-of-the-art results.

Related Works

SRCNN

In order to tackle the problem of having multiple solutions for SISR for any given image, earlier methods mainly focused on constraining the solution space using strong prior information, such as assumptions or characteristics of the high-resolution image. This was mainly achieved using a pipeline for an example-based strategy that exploited internal similarities within an image or by learning mapping functions from external low- and high-resolution exemplar pairs.

To address these limitations more effectively, SRCNN was developed in 2014. Deep convolutional neural networks are essentially equivalent to the pipelines of example-based methods; however, hidden layers are utilized to implicitly learn the mappings and further handle tasks such as patch extraction and aggregation.

Methodology

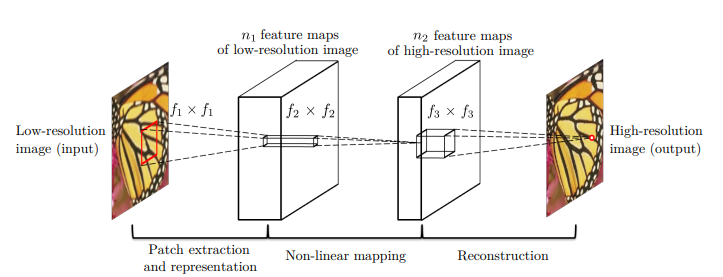

SRCNN is composed of three main operations: patch extraction and representation, non-linear mapping, and reconstruction. All three operations are implemented using convolutional layers.

The patch extraction and representation layer extracts overlapping patches from the low-resolution image and represents each patch as a set of feature maps. This is achieved through a convolutional layer with \(n_1\) convolutions on the image using a kernel size of \(c \times f_1 \times f_1\). Thus, the output is composed of \(n_1\) feature maps.

The non-linear mapping operation maps each high-dimensional vector onto another high-dimensional vector. Conceptually, each vector is a representation of a high-resolution patch. While it is possible to add more layers to this operation, doing so increases the training time.

The reconstruction layer aggregates the high-resolution patches to generate the final high-resolution image. This is accomplished through a convolutional layer that acts as an averaging filter. If the representations are in another domain, this convolutional layer will first project them back into the image domain. The output is expected to closely resemble the ground truth.

To learn the network parameters, Mean Squared Error (MSE) is used as the loss function because MSE favors a high PSNR.

Fig 1. An overview of the SRCNN architecture [1].

Fig 1. An overview of the SRCNN architecture [1].

Experiments and Results

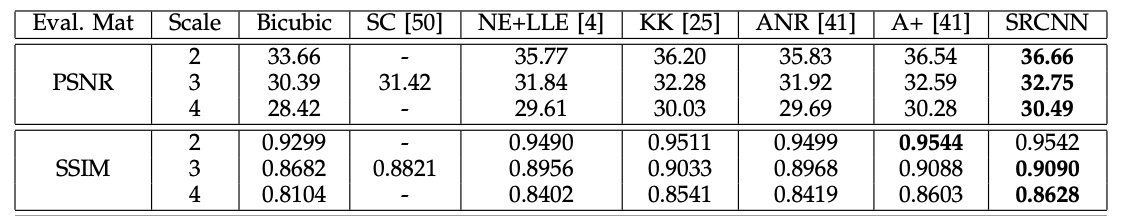

In terms of benchmark datasets, SRCNN showed superior performance to state-of-the-art methods in most evaluation scores. Specifically, SRCNN achieved average gains on PSNR up to 0.17 dB higher than the next approach as shown in the table below, which gives test scores from the Set5 dataset. This improvement was consistent across other datasets.

Fig 2. PSNR and SSIM comparison of SRCNN and other SR models [1].

Fig 2. PSNR and SSIM comparison of SRCNN and other SR models [1].

Overall, SRCNN provided a foundation for using CNNs in SISR, marking a significant step forward in the field. However, despite their pioneering role, SRCNN still has certain limitations. These limitations can be addressed with more advanced methods such as residual blocks, dense blocks, and attention. The implementation of these techniques has led to the creation of new architectures that are more powerful than SRCNN. Two of these architectures, SwinIR and HAT are discussed below.

SwinIR

SwinIR (Swin Transformer for Image Restoration) represents a significant leap in the advancement of image restoration tasks as it overcomes many key limitations of traditional CNN-based architectures. Most notably, SwinIR utilizes the self-attention mechanisms within the Swin transformer to allow for content-based interactions, efficiency with long-range dependencies, high-resolution inputs, and overall better performance over CNNs.

Methodology

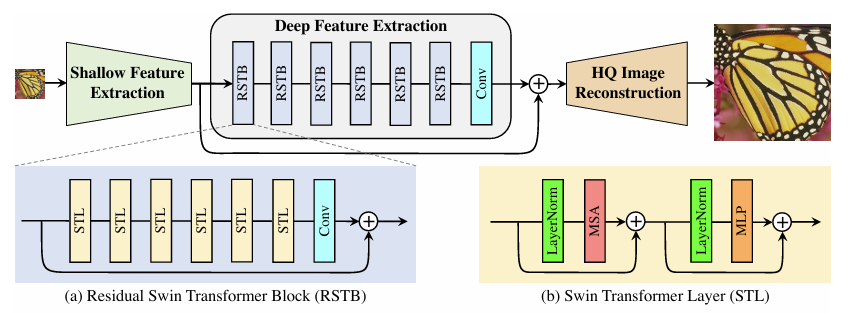

The SwinIR model is designed with a modular architecture comprising three distinct stages: shallow feature extraction, deep feature extraction, and high-quality image reconstruction. This hierarchical design ensures that both low- and high-frequency information is effectively captured and utilized during image restoration.

First, the shallow feature extraction stage employs a single 3x3 convolutional layer to extract low-level features from the input image. Denoted as \(F_0\), these features preserve the low-frequency components of the image, which are crucial for maintaining structural integrity. This stage ensures stable optimization and prepares the input for subsequent deep feature extraction.

Then, the deep feature extraction module makes up the core of the SwinIR architecture, designed to recover high-frequency details and complex patterns within the image. It comprises a stack of Residual Swin Transformer Blocks (RSTBs), each containing several Swin Transformer layers. Key components of these blocks include:

- Swin Transformer Layer (STL): Within each RSTB, STLs operate on non-overlapping local windows, computing self-attention separately for each window. There is a shifted window mechanism that alternates between regular and shifted partitions which allows for cross-window interaction while maintaining computational efficiency.

- Residual Connections: Each RSTB also has residual connections that bypass intermediate layers which helps stabilize training and gradients. The final output of each block is refined with a 3x3 convolutional layer to help enhance the inductive bias of the features learned and establish a stronger foundation for combining both shallow and deep features later on in the network.

Fig 3. An overview of the SwinIR architecture [2].

Fig 3. An overview of the SwinIR architecture [2].

Finally, in the reconstruction stage, the learned shallow and deep features are fused to generate a final high-quality output. This fusion is represented as:

\[I_{RHQ} = H_{REC}(F_0 +F_{DF})\]where \(H_{REC}\) denotes the reconstruction function. For super-resolution tasks, SwinIR employs a sub-pixel convolution layer to upscale the fused features, ensuring spatial alignment and efficient upsampling.

Results

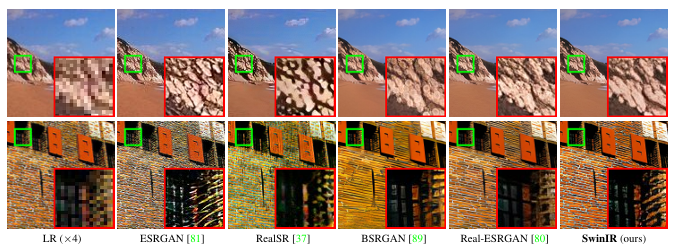

SwinIR achieves state-of-the-art performance across a range of super-resolution tasks. Evaluations on benchmark datasets (e.g., Set5, Set14, BSD100, Urban100, and Manga109) demonstrate its superiority over CNN-based models (e.g., RCAN, HAN) and other Transformer-based methods (e.g., IPT). Analyzing the quantitative results, SwinIR delivers higher PSNR and SSIM scores across various scaling factors (x2, x3, x4), with PSNR gains up to 0.26 dB over leading methods. Due to its efficient use of parameters and faster inference times, SwinIR is also a very competitive model compared to leading lightweight image SR methods and reaches a PSNR improvement of up to 0.53 on different benchmark datasets.

Fig 4. Comparison of various real-world image SR architectures to SwinIR [2].

Fig 4. Comparison of various real-world image SR architectures to SwinIR [2].

SwinIR significantly advanced the field of image restoration by integrating the Swin Transformer into a modular and efficient architecture. Its ability to balance local and global attention mechanisms, coupled with hierarchical feature extraction, established it as a benchmark for super-resolution and other restoration tasks. However, while SwinIR excels in many aspects, it is not without limitations, particularly in scalability and computational demands for very high-resolution images or real-time applications. In the next section, we will explore how HAT builds upon the foundations laid by models like SwinIR, addressing its limitations and pushing the boundaries of image restoration even further.

HAT

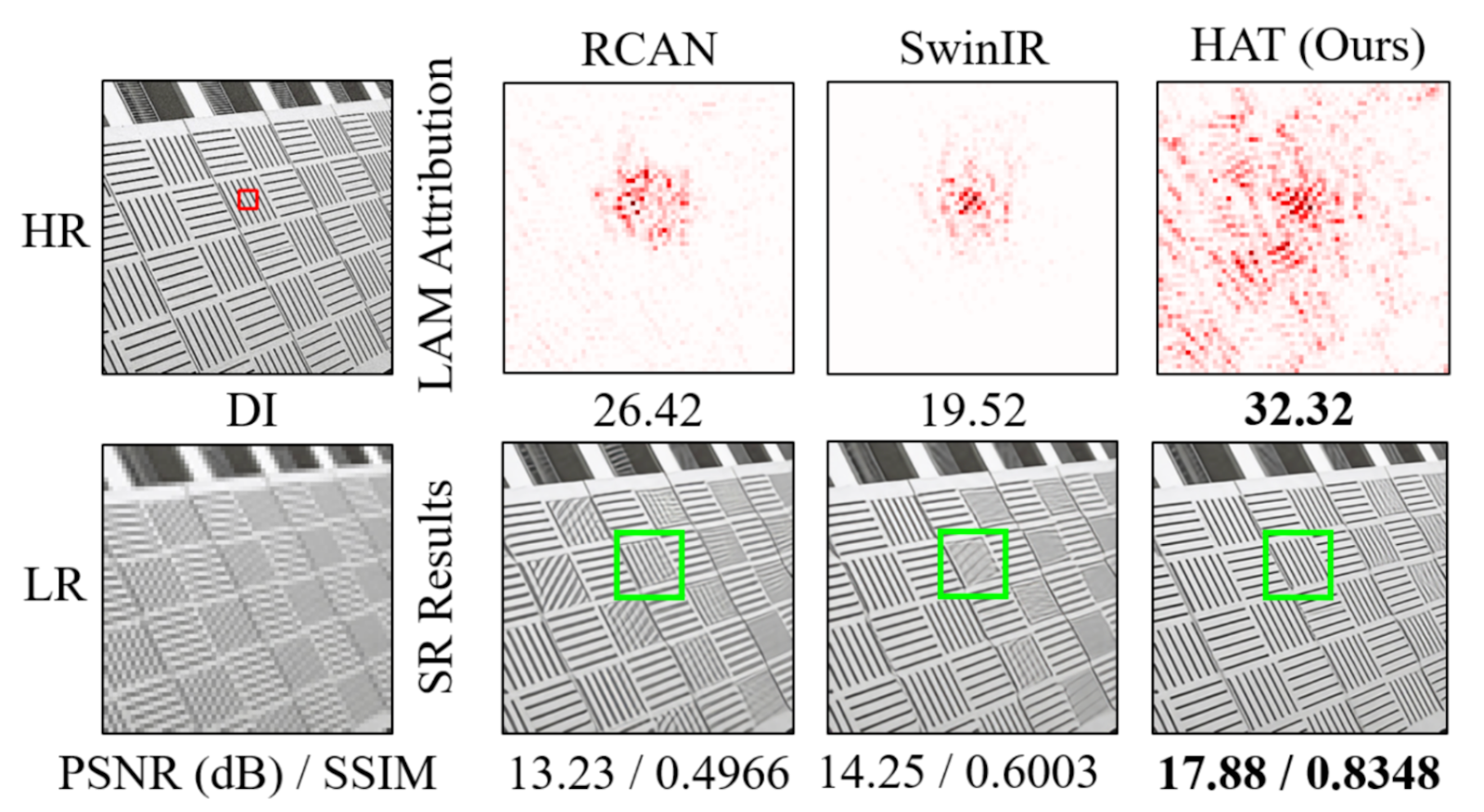

Intuitively, SwinIR performs better than CNN-based models because the self-attention mechanism captures global information better than convolution-based approaches. However, attribution analysis using LAM contradicts this intuition: SwinIR activates the same if not less pixels compared to CNN-based networks like RCAN, and its shift window mechanism causes blocking artifacts and weak cross-window interactions. To address these issues, the Hybrid Attention Transformer (HAT) introduces hybrid attention mechanisms that combine channel attention and self-attention. HAT incorporates self-attention, channel attention, and overlapping cross-attention to improve pixel activation. Additionally, HAT leverages pre-training on large datasets (ImageNet) to enhance its performance, achieving state-of-the-art results in SISR.

Visualizing Pixel Activation Using LAM

Super-resolution networks are different from classification networks in that classification networks output the class that is global to the whole image, while SR networks output images that spatially correspond to the local pixels in the input image. Local Attribution Map (LAM) is a technique to interpret super-resolution networks based on the integrated gradient method.

To calculate pixel activation, LAM takes the input image and a baseline image, which is a blurred version of the input, and then uses a progressive blurring path function \(\gamma_{\text{pb}}\) to calculate the path integrated gradient along the path to change the baseline image to the input image. The blurring path function \(\gamma_{\text{pb}}\) defines a path to change the baseline image to the input image, so the activation can be observed by comparing the change from the baseline to the input. In practice, the integration is approximated with a sum of the gradient at each step of \(\gamma_{\text{pb}}\), as shown below.

\[\text{LAM}_{F,D}(\gamma_{\text{pb}})_{i}^{\text{approx}} := \sum_{k=1}^{m} \frac{\partial D \big(F(\gamma_{\text{pb}}(\frac{k}{m}))\big)}{\partial \gamma_{\text{pb}}(\frac{k}{m})_{i}} \cdot \big(\gamma_{\text{pb}}(\frac{k}{m}) - \gamma_{\text{pb}}(\frac{k+1}{m})\big)_{i}\]Here, the summation adds the gradients from \(k=1\) to \(k=m\), and each k value represents a step in the path to modify the baseline image to the input image.

When comparing the LAM result between RCAN, SwinIR, and HAT, the HAT model activates significantly more pixels than previous models due to its novel hybrid attention blocks.

Fig 5. The LAM results for various networks illustrate the significance of each pixel in the input LR image when reconstructing the patch outlined by a box. The Diffusion Index (DI) measures the range of pixels involved in the reconstruction process, with a higher DI indicating a broader range of utilized pixels. HAT uses the largest number of pixels for reconstruction. [3].

Fig 5. The LAM results for various networks illustrate the significance of each pixel in the input LR image when reconstructing the patch outlined by a box. The Diffusion Index (DI) measures the range of pixels involved in the reconstruction process, with a higher DI indicating a broader range of utilized pixels. HAT uses the largest number of pixels for reconstruction. [3].

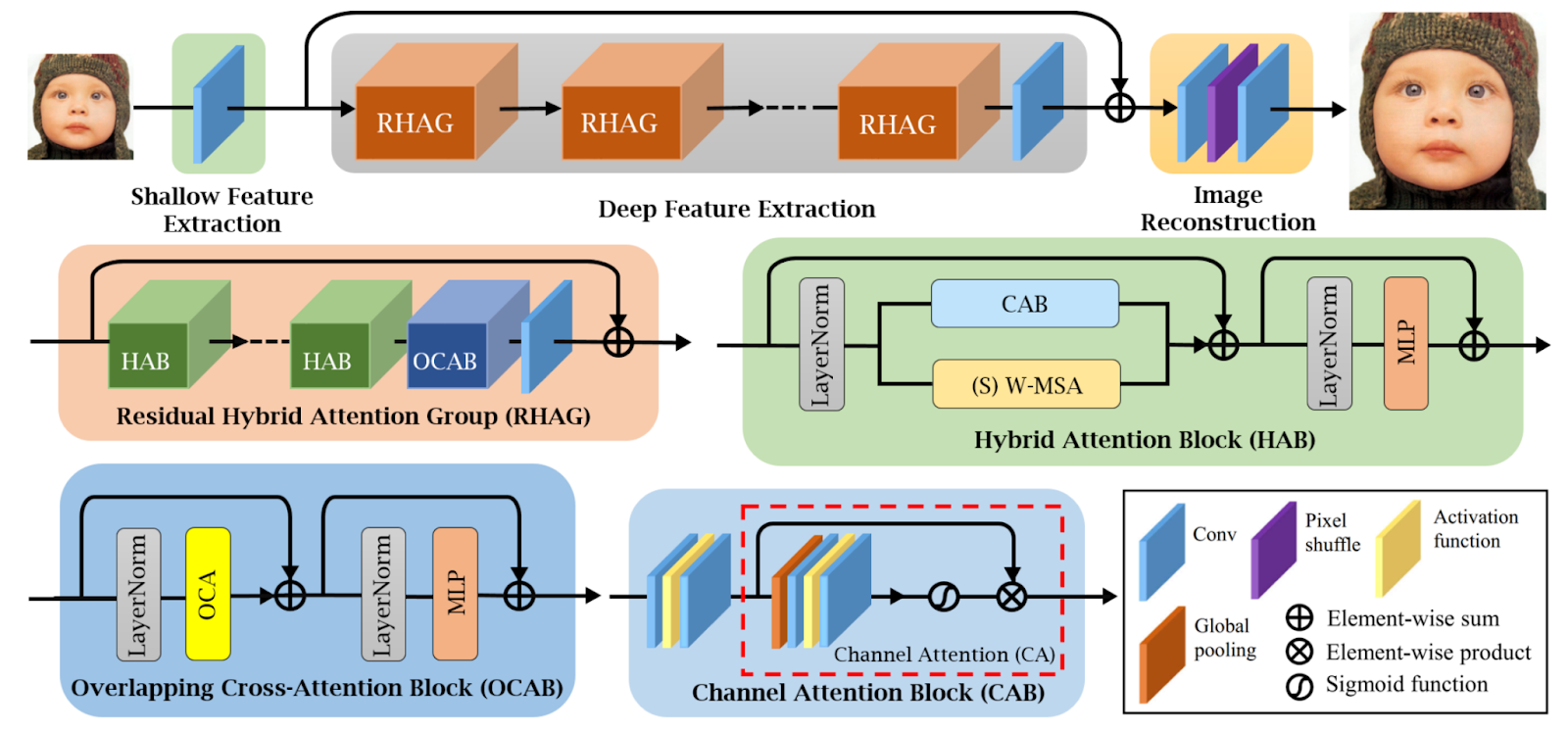

Fig 6. The overall architecture of HAT and the structures of RHAG and HAB [3].

Fig 6. The overall architecture of HAT and the structures of RHAG and HAB [3].

Given an input low-resolution image, the network first uses a convolution layer to extract shallow features. Then, the model applies a series of Residual Hybrid Attention Groups (RHAG) to attend to deep features that are very specific to the variations in the data sample. Another convolution layer is used to extract deep features at the end of the deep feature extraction block. A global residual connection is used to fuse the shallow and deep features. At the end, transpose convolution layers are used to reconstruct the image.

Implementation of the HAB

To improve pixel activation, RHAG also uses an Overlapping Cross-Attention Block (OCAB) to establish connections across windows by computing cross-attention. RHAG also utilizes a novel Hybrid Attention Block (HAB) that incorporates a Channel Attention-based Convolution block (CAB) along with the original Window-based Multi-head Self-Attention (W-MSA) to help the transformer block to get better visual representation ability. HAB can be implemented in Pytorch as below.

class HAB(nn.Module):

"""Hybrid Attention Block with convolutional and attention mechanisms."""

def __init__(self, dim, input_resolution, num_heads, window_size=7, shift_size=0, conv_scale=0.01):

super().__init__()

self.norm1 = nn.LayerNorm(dim)

self.attn = WindowAttention(dim, window_size, num_heads)

self.conv_block = CAB(dim) # convolutional attention block

self.norm2 = nn.LayerNorm(dim)

self.mlp = Mlp(dim, hidden_features=int(dim * 4))

self.shift_size = shift_size

self.conv_scale = conv_scale

def forward(self, x, x_size):

h, w = x_size

shortcut = x

# convolutional feature extraction

conv_x = self.conv_block(x)

# cyclic shift and window attention

if self.shift_size > 0:

x = torch.roll(x, shifts=(-self.shift_size, -self.shift_size), dims=(1, 2))

x_windows = window_partition(x, self.window_size)

attn_x = window_reverse(self.attn(x_windows), self.window_size, h, w)

# combine features and feed through MLP

x = shortcut + attn_x + self.conv_scale * conv_x

x = x + self.mlp(self.norm2(x))

return x

In the implementation, the hybrid attention block includes a window-based self-attention module to interpret deep features and then uses a channel attention block for local feature extraction and global context modeling. HAB also uses cyclic shift to improve information flow across windows and a learnable scaling factor to balance the contributions of convolutional and attention outputs.

Internally, the channel attention block uses adaptive average pooling to compress spatial information into a global descriptor for each channel. It then squeezes and unsqueezes along the channel dimension through convolution to encode important channel-wise semantic information, as shown in the implementation below.

class ChannelAttention(nn.Module):

"""Channel attention used in RCAN."""

def __init__(self, num_feat, squeeze_factor=16):

super(ChannelAttention, self).__init__()

self.attention = nn.Sequential(

nn.AdaptiveAvgPool2d(1),

nn.Conv2d(num_feat, num_feat // squeeze_factor, 1, padding=0),

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(num_feat // squeeze_factor, num_feat, 1, padding=0),

nn.Sigmoid())

def forward(self, x):

y = self.attention(x)

return x * y

Results

During the training of HAT, same task pre-training on the full ImageNet is shown to improve model performance. The model is then fine-tuned with the DF2K dataset for evaluation. Two super-resolution scales, SRx2 and SRx4, are trained.

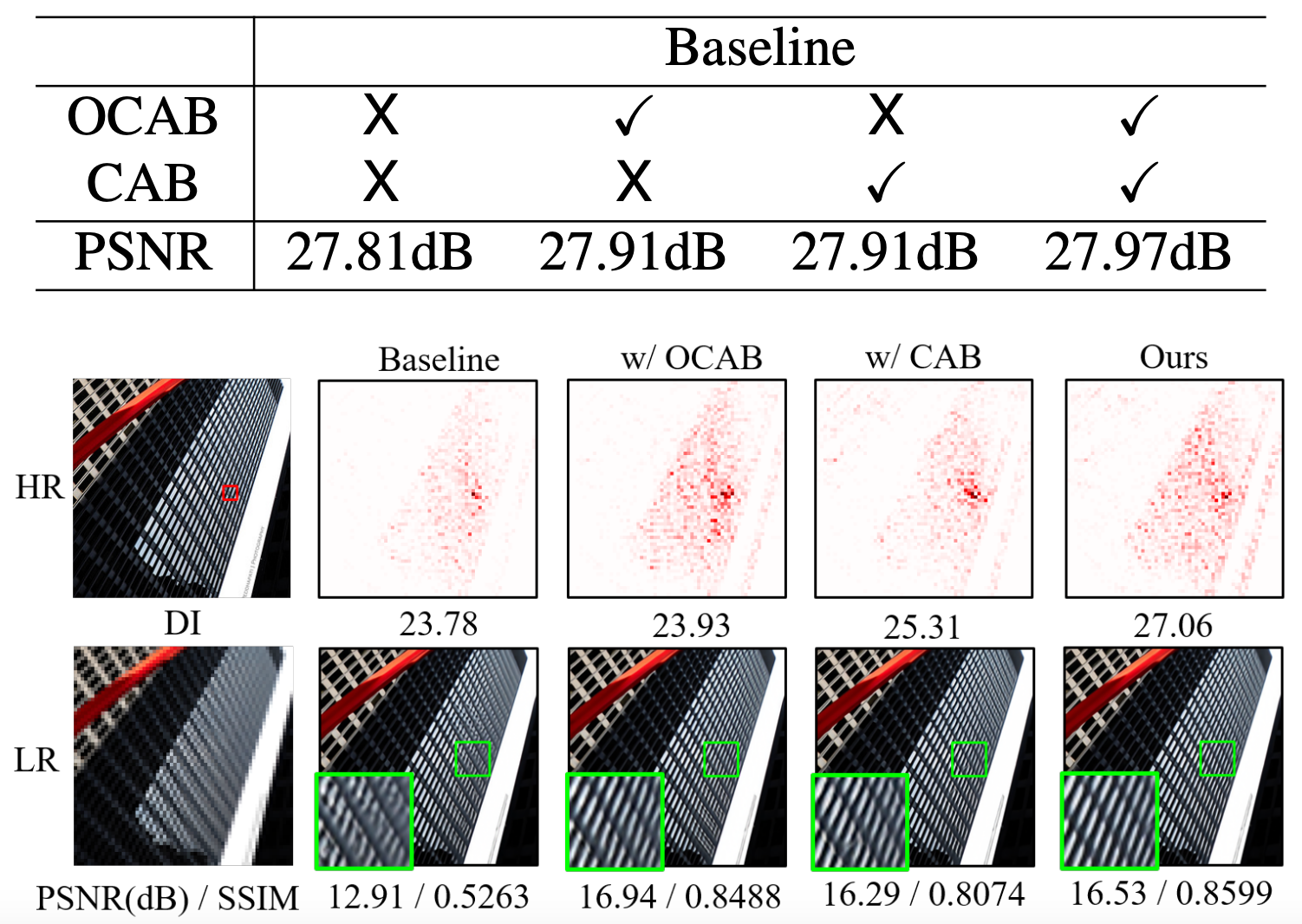

The effectiveness of CAB and OCAB are evaluated in a controlled environment and found to improve the performance in peak signal-to-noise ratio by 0.1 dB.

Fig 7. The effectiveness of OCAB and CAB on pixel activation and PSNR [3].

Fig 7. The effectiveness of OCAB and CAB on pixel activation and PSNR [3].

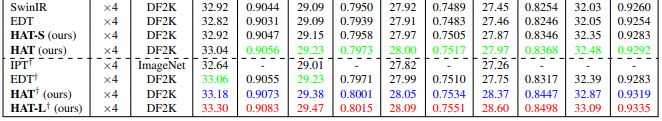

Furthermore, the PSNR and SSIM of HAT on the Set5 dataset using SRx4 are shown below.

Fig 8. PSNR and SSIM metrics of various SR models on various testing datasets [3].

Fig 8. PSNR and SSIM metrics of various SR models on various testing datasets [3].

The fourth and fifth columns give the PSNR and SSIM scores on the Set5 dataset. Of note are SwinIR’s scores of 32.92 and 0.9044 at the top and HAT’s scores at the bottom. The HAT models listed differ only in size and pre-training strategy. These show a marked improvement over SwinIR by every HAT model, with the best model giving an improvement of 0.38 dB in PSNR and 0.0039 in SSIM. Additionally, both of these models show a drastic improvement over SRCNN.

Experiments

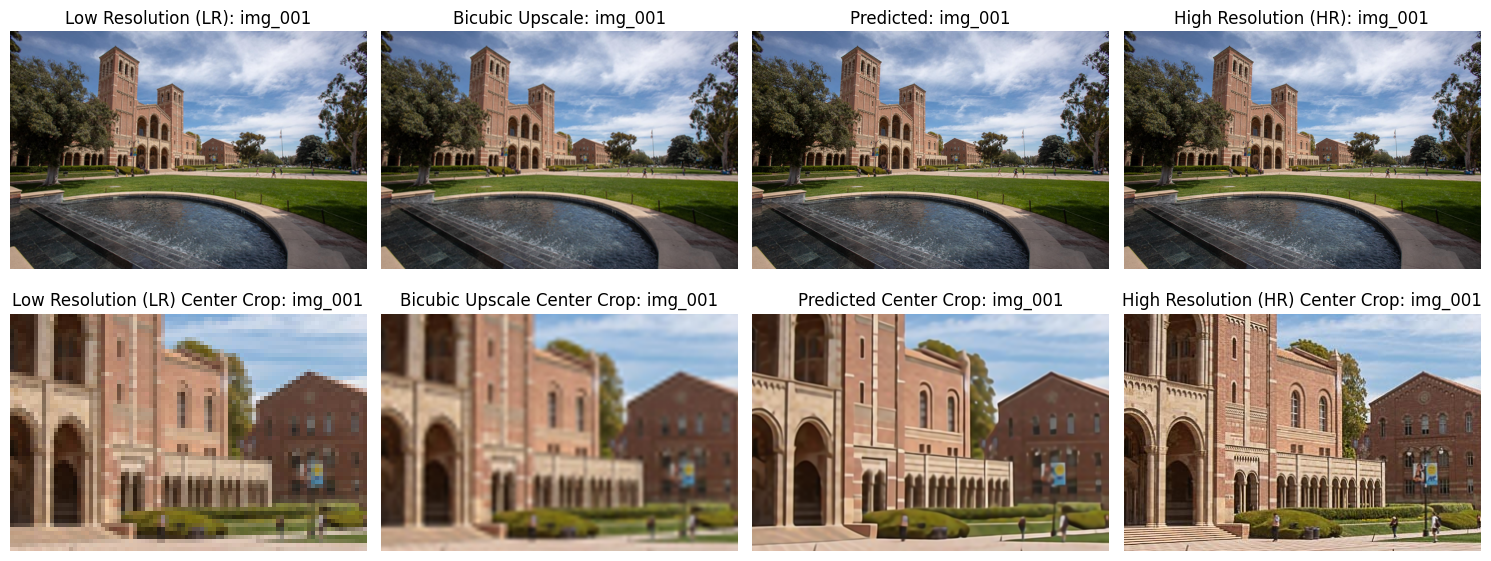

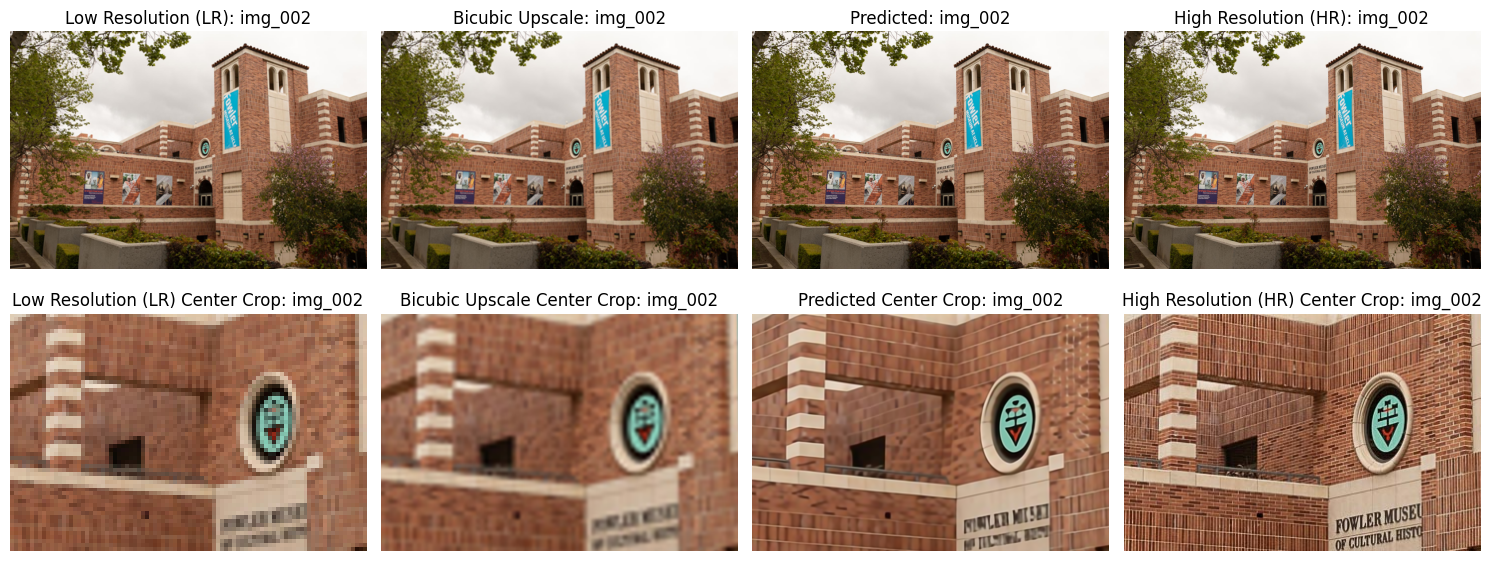

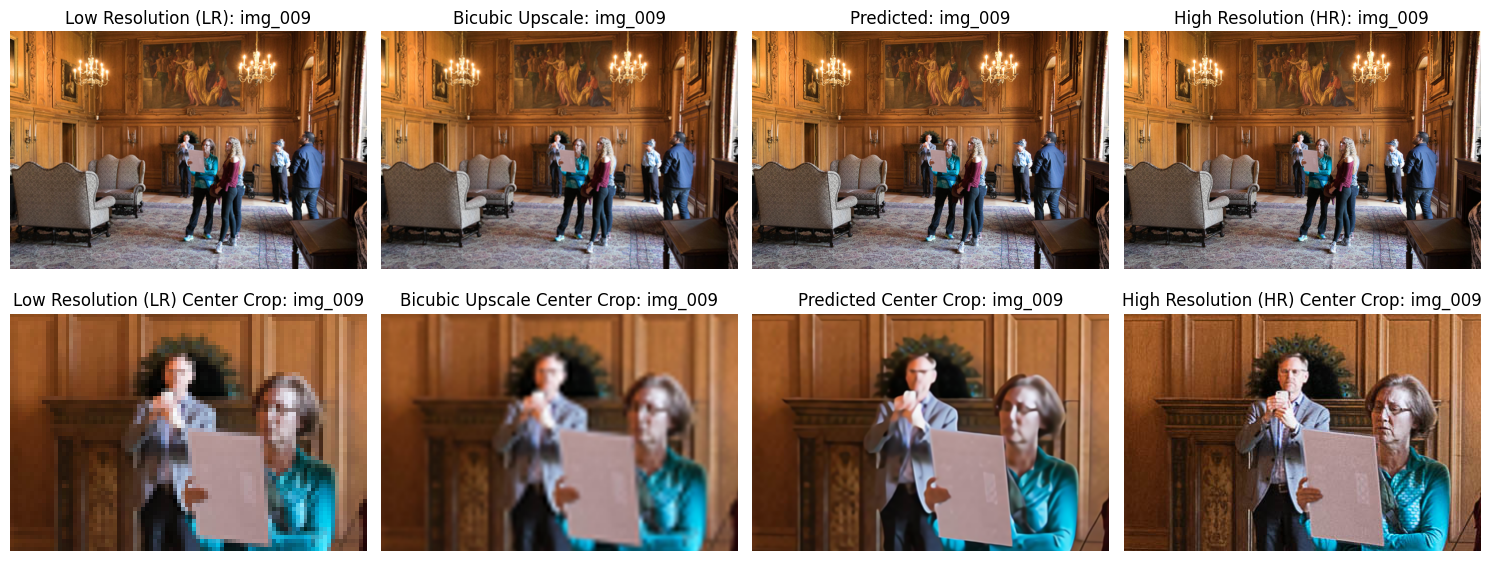

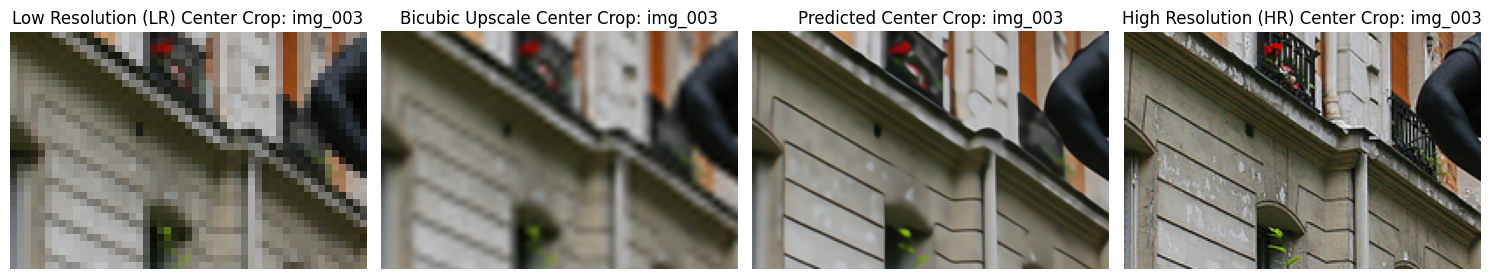

We applied the HAT model to a few open-source images found on the UCLA newsroom website including images of campus architecture and people, as well as the Urban100 SRx4 (upscaling by a factor of 4) test dataset. We used the bicubic interpolation method to downgrade the high-resolution images and applied the HAT SRx4 model pre-trained on ImageNet.

From the results, we see that the model is better at reconstructing objects including buildings and architecture as compared to humans and faces. We think this is due to the characteristics of the pre-training dataset ImageNet, which contains a large amount of objects compared to humans. We expect that finetuning the model with few-shot learning would make it perform better at reconstructing these images. Some examples of reconstructed UCLA images and their center crops are shown in the figure, and they are compared to the input low resolution, the baseline bicubic interpolation upscaling, and the ground-truth high-resolution image.

Fig 9. Reconstruction results of HAT SRx4 ImageNet pre-trained model on images of UCLA.

Fig 9. Reconstruction results of HAT SRx4 ImageNet pre-trained model on images of UCLA.

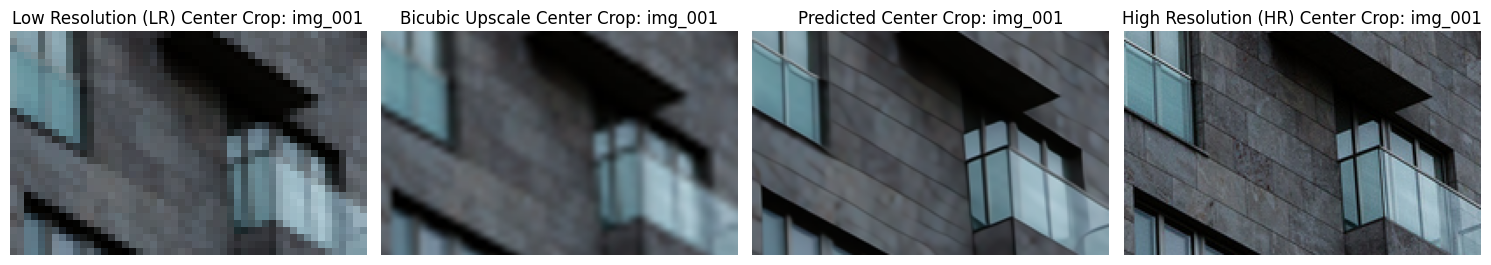

Below are additional results from testing on the Urban100 dataset since we observed that the model is better at reconstructing architectural results.

Fig 10. Reconstruction results of HAT SRx4 ImageNet pre-trained model on Urban100 dataset.

Fig 10. Reconstruction results of HAT SRx4 ImageNet pre-trained model on Urban100 dataset.

| PSNR | SSIM | |

|---|---|---|

| UCLA | 27.0516 | 0.7833 |

| Urban100 | 28.3642 | 0.8445 |

Fig 11. The result metrics of our tests on UCLA and Urban100.

As can be seen above, the model achieves great, albeit not perfect, performance. The predicted images in both datasets show a slight lack of granularity and fine detail. Overall, however, the experiments support the claim that more pixel activation in the input image would lead to a better reconstruction result in the super-resolution task.

Demo

The results from above can be replicated using the demo Colab notebook in the Code section below. First, download the HAT folder from the Google Drive link below and add it to your own Google Drive. Then, follow the instructions in the Colab Notebook. The provided folder already has the results of our own tests in the results folder. It also comes with some models and datasets pre-downloaded.

Code

HAT Codebase: GitHub

HAT Demo: Colab

HAT Folder: Drive

Conclusion

The results of our experiments with HAT demonstrate the extraordinary potential of super-resolution models. Our images show that the model performs admirably on diverse datasets. The potential impact of this technology on society is difficult to quantify, as it has the potential to save lives if successfully applied to areas such as medicine or surveillance, although as with any technology, there are moral concerns to consider. HAT is not without its limitations, as can be seen in some of the predicted images, particularly the ones involving people. Due to the limitations of the training dataset, it was difficult for the model to predict intricate details in its reconstructions of our test sets. Further research is already being conducted to solve these issues, and only a year after the release of HAT new models have been released that outperform HAT in certain datasets, such as HMA and DRCT, showing that the future of image super-resolution is bright.

References

[1] Dong, Chao, et al. “Image Super-Resolution Using Deep Convolutional Networks” arXiv:1501.00092. 2014.

[2] Liang, Jingyun, et al. “SwinIR: Image Restoration Using Swin Transformer” arXiv:2108.10257. 2021.

[3] Chen, Xiangyu, et al. “Activating More Pixels in Image Super-Resolution Transformer” arXiv:2205.04437. 2023.

[4] Zhang, Kai, et al. “Deep Unfolding Network for Image Super-Resolution” arXiv:2003.10428. 2020.

[5] Gu, Jinjin, et al. “Interpreting Super-Resolution Networks with Local Attribution Maps” arXiv:2011.11036. 2020.