Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training Applications and Extensions

With the strong data-driven nature of training Computer Vision models, the demand for reliably annotated data is quite high. Manually labeling datasets is very time consuming and a bottleneck to progression. Another bottleneck comes from training large, specialized models from scratch on these big datasets, which is computationally expensive. In the mid 2010s, the method of pretraining deep ConvNets on ImageNet before fine-tuning on a specific downstream image classification task was popular. This effectively set a baseline of visual features that newer models could build off of. However, multi-modal relationships between image and text weren’t strong enough and there was still the need to fine-tune models. We focus this blog on exploring CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training). The purpose of CLIP is to perform zero/few-shot learning (the ability to classify images seeing little to no prior examples). The idea is that fine-tuning would not be compulsory. CLIP achieved state of the art results in zero shot. Also, CLIP has been extended and improved, we’ll go into deeper detail below. CLIP opened the door for CLIPScore, a unique and preferred evaluation metric for image captioning. CLIP’s rich text encoder is also used in latent diffusion models (LDM) for text conditioning. FALIP also brought improvements and variations to the original CLIP.

- Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision (CLIP)

- FALIP: Visual Prompt as Foveal Attention Boosts CLIP Zero-Shot Performance

- CLIPScore

- Running the CLIP Codebase

- Implementing Our Own Ideas: Text-to-Image Search with CLIP

- Reference

Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision (CLIP)

Background

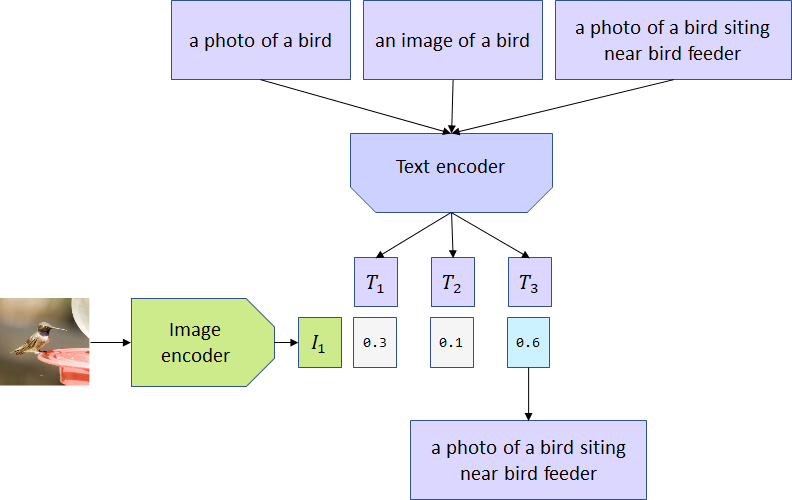

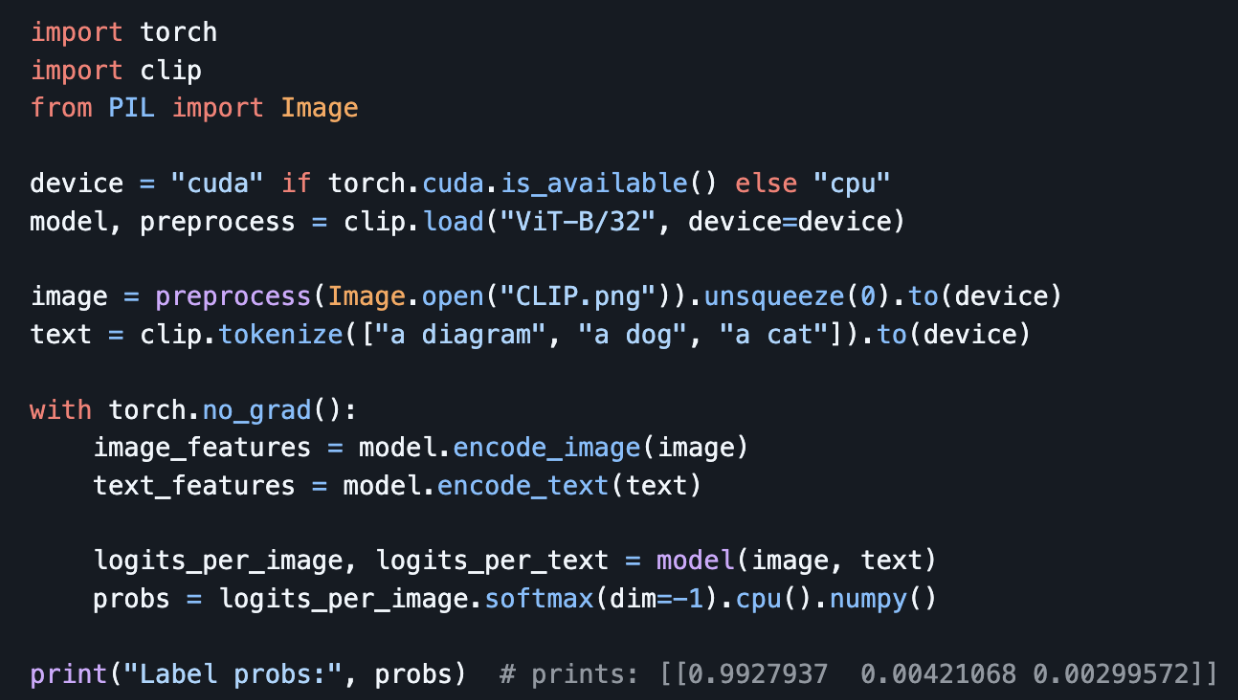

CLIP refers to Contrastive Language Image Pretraining, which is a method in which two models: the image and text encoders, are trained jointly, with the purpose of being able to classify (or essentially caption) images, even if they do not fall into preset class categories present at training time. In this paper, the authors propose the CLIP method as a more efficient zero-shot solution, allowing for almost double the accuracy for labeling on ImageNet over traditional zero-shot methods such as bag-of-words and transformer language models. CLIP accomplishes this via maximizing the similarity between correct image and text embedding pairs and minimizing the similarity for incorrect matches, using labeled data. Training involves the usage of image-text pairs, that the model maps to the same embedding space, and can calculate similarity scores. Overall, CLIP serves as a significant improvement over traditional Zero-Shot approaches via contrastive learning using a shared embedding space for text and images.

Methodology

In the paper, the authors propose training CLIP via building a dataset of 400 million image-label pair samples as they noted the varying and sparse nature of metadata available for other major image caption datasets. The next consideration is the models to use for the text and image encoders. In the paper, the authors experiment with various Resnet models as well as vision transformers for the image encoders, and use the transformer presented in “Attention is All You Need” for the text encoders. For the training process, firstly, the (image, text) pairs are created via taking the class label for each image, and treating it as text (rather than a one-hot encoded class). Then, they feed the text through the text transformer while feeding the input image through the image encoder (either Resnet or ViT), resulting in feature embeddings for both the text and image separately. Then, the concept of a “shared” embedding is implemented via calculating cosine similarities between the features for the image and text embeddings. Then, cross-entropy loss is utilized on the predicted similarities, optimizing for greater similarity between correct image-text labels and lower similarity between incorrect labels.

Fig 1. Clip model example input. [3].

Key Functional Features

The key functional difference between CLIP and other Zero-Shot models is that traditionally, zero-shot had been using semantic features as the way to embed descriptive information about images. CLIP improved on this by using natural language as the semantic features to match with the images, as this allows for a much stronger and generalizable embedding than a fixed algorithm for feature extraction. The second innovation is the way the CLIP model utilizes attention mechanisms to accomplish its image-text correspondence goal. The use of attention in the vision transformer to encode the image into descriptive features and the text encoder transformer allows for extracting more descriptive information from the input, and in the context of the text, can develop relationships between the different words. This further contributes to the strength of the CLIP models because by the time the cosine similarity between the embeddings is calculated, there is a sense that the embeddings themselves are strong descriptors for the inputs.

Applications

The applications of the CLIP model are numerous, as the ability to match text embeddings to images allow for powerful real-world implementations. The first such implementation would be in the realm of exactly what CLIP was trained for: giving a trained model an arbitrary image (that was not trained on) and having it give a text description for that image. This could be integrated into applications such as search engines, where an image is dropped and can perform a search for similar such images, or use the reverse process to go from the text to the image. Another application could be with fine tuning CLIP models for more specific applications. For example, if one wanted to train a CLIP model in a different language, it would be possible to replace the training set with translations of the labels. Or in the case of a more specialized requirement, such as labeling various types of fish in the sea, the current CLIP model could be finetuned with data resembling (fish image, fish text label) in order to be more specialized for that task.

Results and Discussion

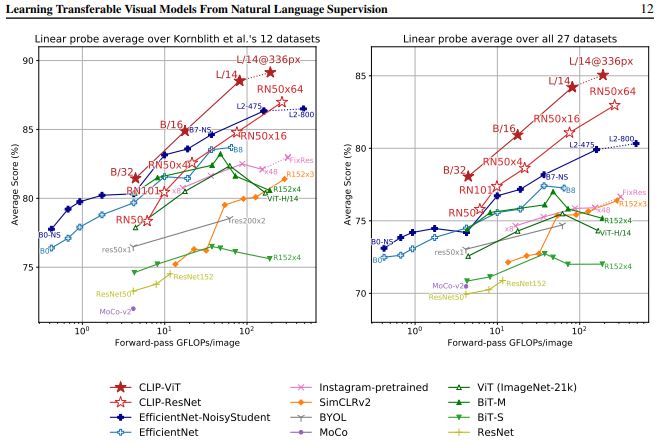

CLIP’s results are quite strong, demonstrating a large improvement from other zero-shot and general image classification models in the past. Below are these improvements visualized, showing the relative accuracy compared to other competitive models on a 27-dataset test (to demonstrate CLIP’s ability to tackle a broad range of problems).

Fig 2. Clip vs other CV Models on 27-dataset evluation. [1].

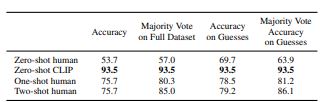

In addition, the researchers of the paper explored how CLIP performs compared to humans. Particularly, they both evaluated on the Oxford IIT Pets dataset, and the CLIP model outperformed the humans significantly, by around 18% in terms of accuracy. However, the researchers did note one pitfall of CLIP compared to humans, and it is that with just one extra class sample, humans had a remarkably better ability to learn the class. This reveals that humans are more robust at generalizing to new tasks, even provided with very few samples. However, considering the broad range of data that CLIP was trained on, CLIP performs better overall. This implies that there might be other methods that allow a model to generalize as well, and as efficiently as humans can.

Fig 3. Clip vs humans on Oxford IIIT Pets Dataset. [1].

Overall, CLIP is a revolutionary concept in the area of zero-shot learning that allows for processing of large quantities of data for significant underlying understanding of the relationship between text and images. The results of the paper demonstrate that the usage of attention and contrastive loss in a shared embedding space is key to furthering understanding in multimodal (text, image) relationships.

FALIP: Visual Prompt as Foveal Attention Boosts CLIP Zero-Shot Performance

Background

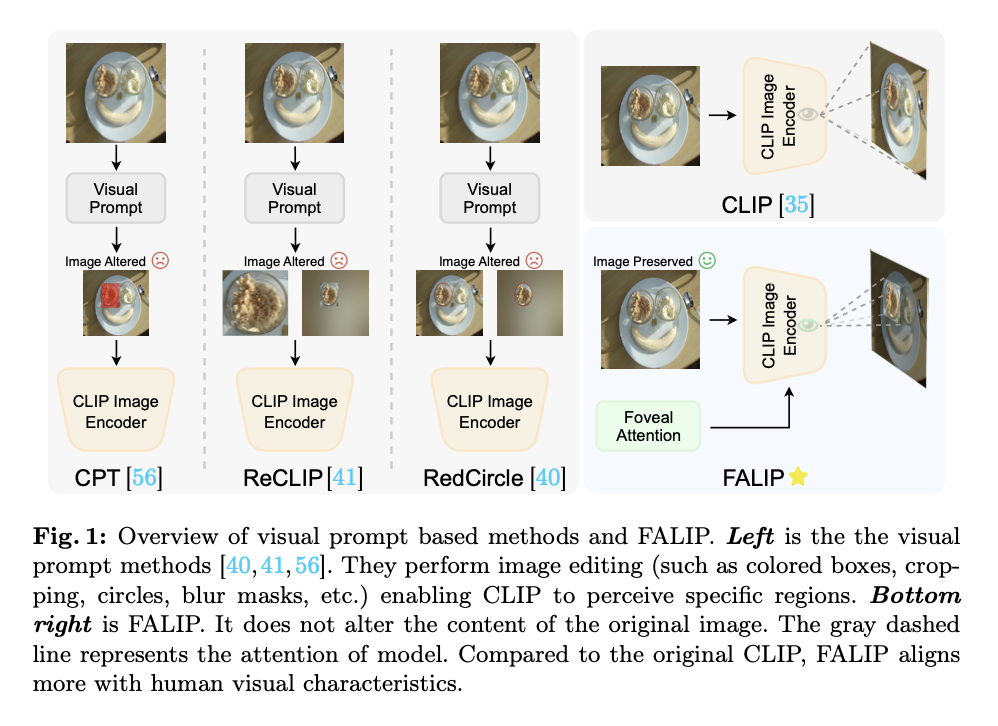

FALIP is introduced in this paper as a novel method to enhance the zero-shot performance of the CLIP model. Its key strength lies in achieving this enhancement without modifying the original image or requiring additional training. While the baseline CLIP model already demonstrates impressive zero-shot performance across various tasks, previous methods have sought to improve it by employing visual prompts, such as colored circles or blur masks, to guide the model’s attention mechanisms. These visual prompts can effectively direct the CLIP model’s focus to specific regions of the image. However, they compromise the image’s overall integrity, creating a trade-off between preserving image fidelity and boosting model performance.

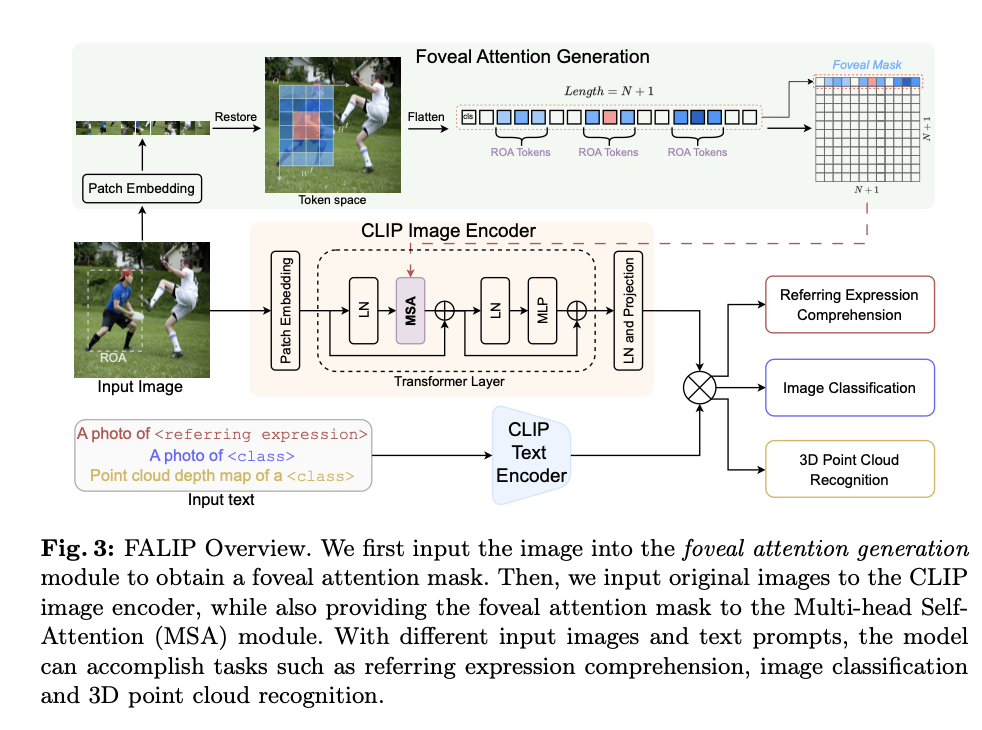

Methodology

The FALIP method for enhancing the CLIP model’s zero-shot performance involves multiple steps. First, the method applies a foveal attention mask to highlight the regions of attention (ROA) in the image. This mask is then integrated into CLIP’s multi-head self-attention module, which is used to conceptualize the relationships between various regions of the image. Finally, the model’s attention is aligned with human-like visual perception, focusing on specific regions without directly modifying the image.

Key Functional Features

The key functional distinctions between the CLIP model and the FALIP method proposed in this paper provide FALIP with a significant advantage over the standard CLIP pipeline. First, FALIP features a plug-and-play design, enabling the direct integration of CLIP models into the FALIP methodology without requiring substantial modifications to the model architecture. Additionally, the computational cost of this modified approach is considerably lower compared to other methods proposed for enhancing the CLIP model. Finally, preserving image integrity is a cornerstone of the FALIP method. It achieves this by guiding the model’s attention while maintaining the essential fidelity of the input image. This is accomplished through adaptive attention guidance, the core of the FALIP method, which inserts foveal attention masks into the multi-head self-attention module, enabling task-specific focus for the model.

Applications

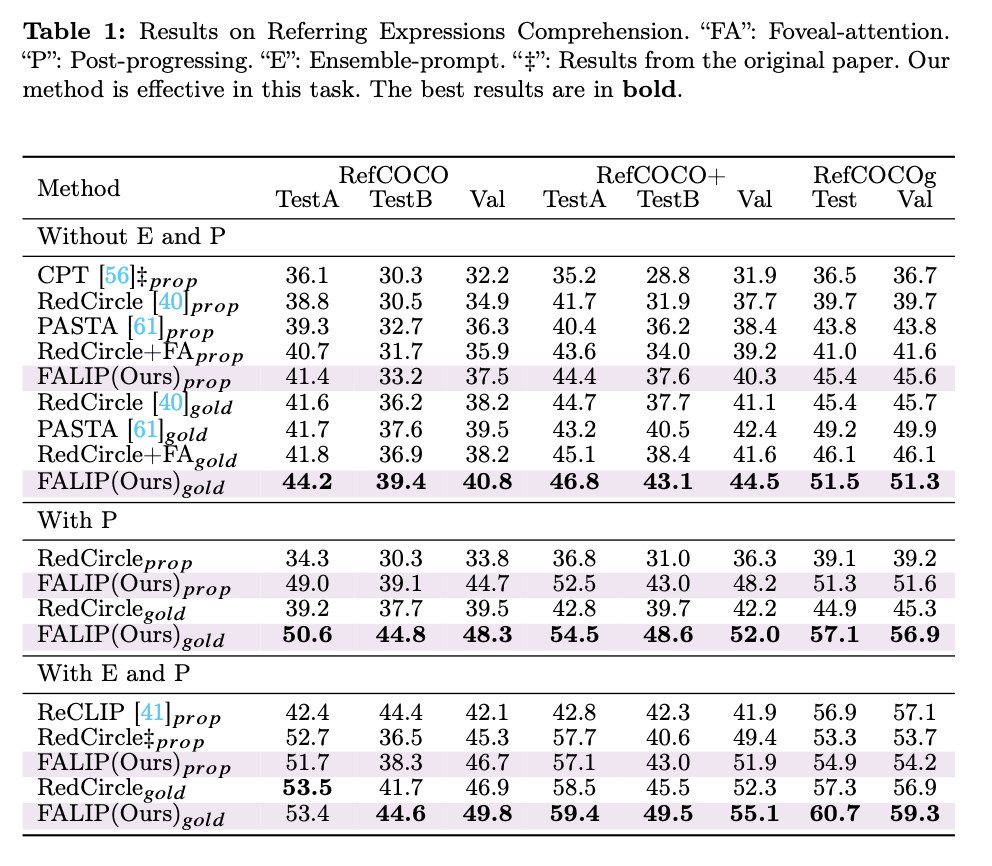

The FALIP protocol was evaluated on several zero-shot tasks, including Referring Expression Comprehension (REC), image classification, and 3D Point Cloud Recognition. For the Referring Expression Comprehension (REC) task, a five-stage process was employed to identify an image region based on a textual description. First, the input, consisting of an image with bounding boxes and a textual description, was processed through the pipeline, where the bounding boxes were transformed into masks. Next, the similarity between the text and the image regions was calculated. A “subtract” operation was then applied to reduce the weights of less relevant similarities. Finally, the best-matching region was selected based on the computed scores. The Image Classification task followed a slightly modified process. In this case, the bounding boxes were converted into a single mask. The protocol then calculated similarity scores by comparing the image to each category’s textual description to determine the best match. For 3D Point Cloud Recognition, the 3D point cloud was projected into six 2D depth maps. The foreground portions of these depth maps were converted into masks, and similarity scores were computed between each view and the category texts. The views were then weighted and combined to produce the final prediction. By evaluating the FALIP protocol across these zero-shot tasks, its effectiveness and versatility in diverse applications were demonstrated.

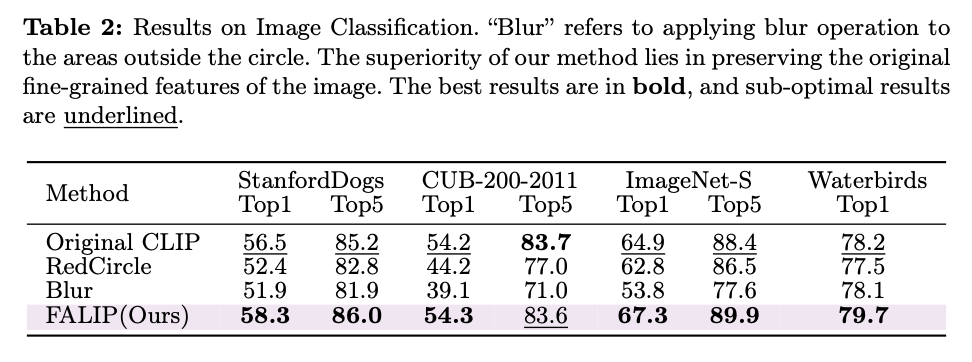

Results and Discussion

The FALIP protocol, as outlined in this paper, has demonstrated competitive results across numerous datasets for tested zero-shot tasks, underscoring its efficacy as a novel and improved method for zero-shot learning with CLIP. At its core, the modification of attention head sensitivity forms the foundation of the proposed technology. This approach was motivated by the discovery that CLIP models exhibit significant variability in their responses to visual prompts and that the attention heads in CLIP possess differing levels of sensitivity to the visual cues provided as input. This variability in sensitivity, which serves as a tunable hyperparameter, offers opportunities for further improvement by enabling testing and adjustment to enhance the effectiveness of visual prompts. Moreover, FALIP’s adaptability for domain-specific problems represents a critical area of interest for researchers and practitioners looking to apply it to other fields of study or industry applications. Overall, these results and insights highlight FALIP’s potential as a powerful and flexible approach for enhancing CLIP’s zero-shot capabilities across various visual understanding tasks, while also paving the way for future advancements in vision-language models.

CLIPScore

Background

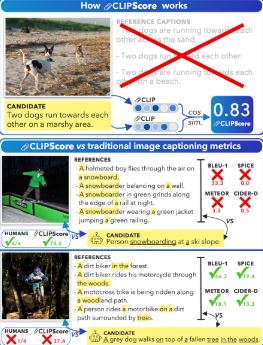

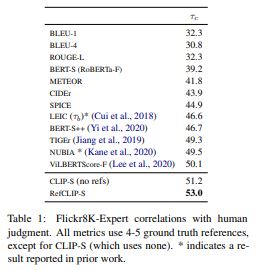

Traditionally, image captioning is evaluated in a reference-based manner, where captions created by machines are compared with those written by humans. This is different from the way humans evaluate captions, which is in a reference-free way. Humans merely see an image and a respective caption before judging its appropriateness. The CLIPScore metric emulates human judgement, evaluating captions without references.

CLIPScore serves as a useful metric to compute vision and language alignment for text-to-image generation models, beyond scores that assess image quality. This helps assess and advance language control in text-to-image generation.

Methodology

Computing CLIPScore goes as follows: Given a candidate caption and image, you pass both through their respective CLIP feature extractors. Then, calculate the cosine similarity of the resultant embeddings.

\[\texttt{CLIP-S}(\textbf{c}, \textbf{v}) = w \times \max(\cos(\textbf{c}, \textbf{v}), 0)\]Where $c$ is the textual CLIP embedding, $v$ is the visual CLIP embedding, $w$ is commonly set to 2.5

If given references, CLIPScore can be extended to incorporate them. Each reference caption will be passed through CLIP’s text encoder, generating a set of embeddings $R$. RefCLIP Score can be computed as:

\[\texttt{RefCLIP-S}(\textbf{c}, \textbf{R}, \textbf{v}) = \text{H-Mean}(\texttt{CLIP-S}(\textbf{c}, \textbf{v}), \max(\max_{\textbf{r} \in \textbf{R}} \cos(\textbf{c}, \textbf{r}), 0))\]Compared to popular $n$-gram matching metrics such as BLEU, CIDEr, SPICE, etc. CLIPScore outperforms them in terms of correlation with human judgement.

Key Functional Features

The key functional features of this protocol include reference-free evaluation, overcoming the limitations of n-gram matching, and providing complementary information. To begin with, the reference-free evaluation feature of CLIPScore enables it to assess caption quality by analyzing both the image and the candidate caption. This process mirrors the human ability to interpret the contextual meaning of captions when provided with images. For example, when babies learn to identify concepts, they are often shown an example of an object (ex. chair) and a verbal command describing the concept, and being able to generalize the concept chair to chairs of different shapes and sizes. Moreover, the feature of overcoming n-gram matching limitations addresses the challenges posed by traditional metrics, which rely on exact word matching with a reference. Finally, the complementary information feature is demonstrated through CLIPScore’s ability to provide additional insights to existing reference-based metrics, as evidenced by information gain experiments.

Results + Applications

The applications of using CLIPScore are numerous, and extend beyond just being used in training for CLIP models. For example, for text-to-image retrieval tasks, CLIPScore could be utilized in order to rank the ability of a search engine to perform this task. Furthermore, CLIPScore can be an additional metric to assess the performance and semantic alignment of text-to-image generative models. In the end, we want to build more intuitive, controllable systems for image generation tasks. One of the key aspects of aligning to human thought is through language. CLIP, which provides a rich source of multimodal (image, text) embeddings can serve as a strong fusion of knowledge towards bridging the gap between user preferences and model generation.

Furthermore, CLIP can be extended to additional modalities. For example, there is CLAP, which is a contrastive language and audio foundation model. This can be similarly used for augmenting text-to-audio generation models and serve as a powerful evaluation metric (CLAP score) for assessing text-to-audio generation alignment with user preferences (e.g. fireworks and people cheering, 90s retro synth).

As demonstrated by the table from the paper, CLIPScore performs much better than adversarial evaluation metrics in determining similarity between text and image embeddings.

Running the CLIP Codebase

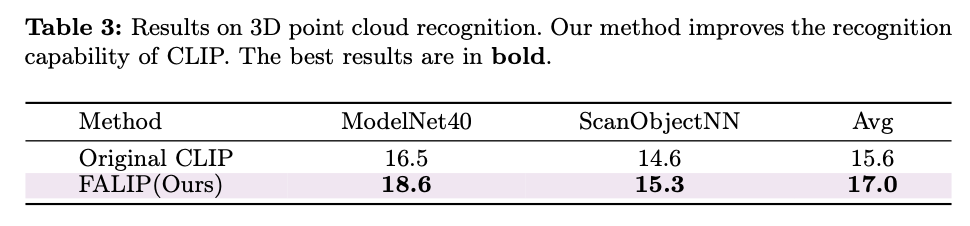

Here we run the CLIP codebase from this GitHub repository to reproduce the results locally.

Test #1

Given an image of a diagram and the labels, “a diagram”, “a dog”, and “a cat”, after running the below code, we get the following predictions. After reproducing this locally, we get similar results.

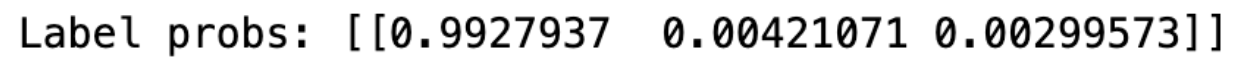

Here are the results we get after running this locally (the scores correspond to diagram, dog, cat respectively)

Test #2

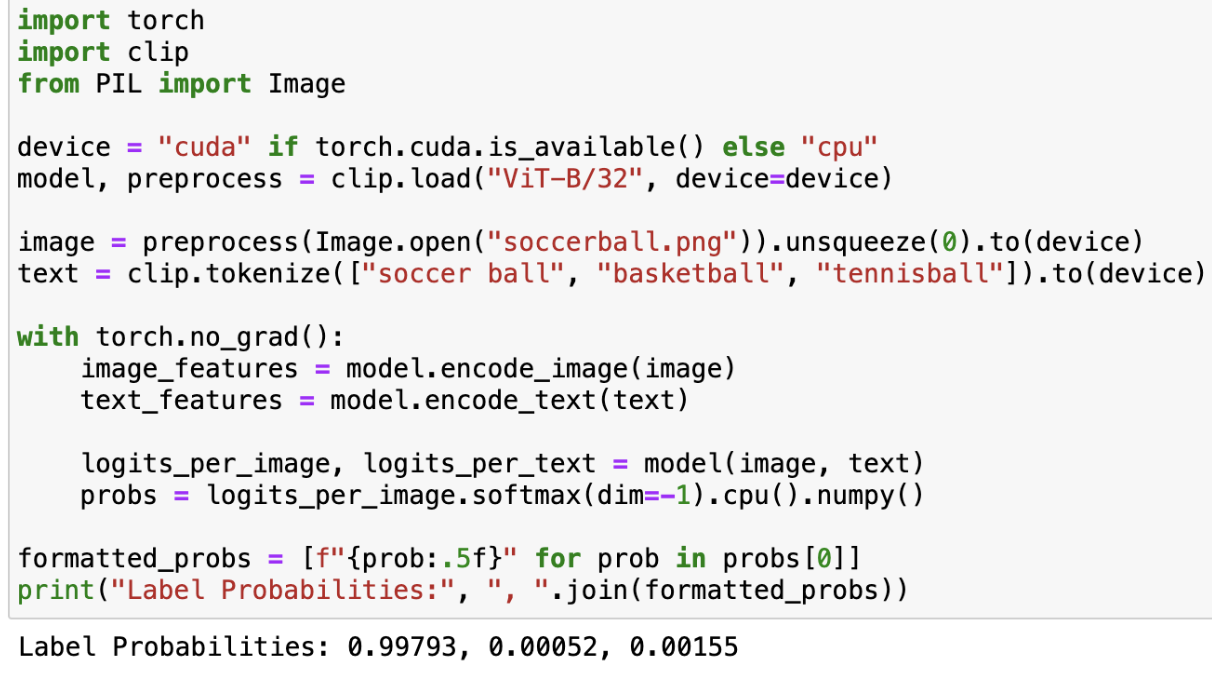

We give a new image of a soccer ball and the labels “soccer ball”, “basketball”, and “tennis ball” (in this order).

Input image:

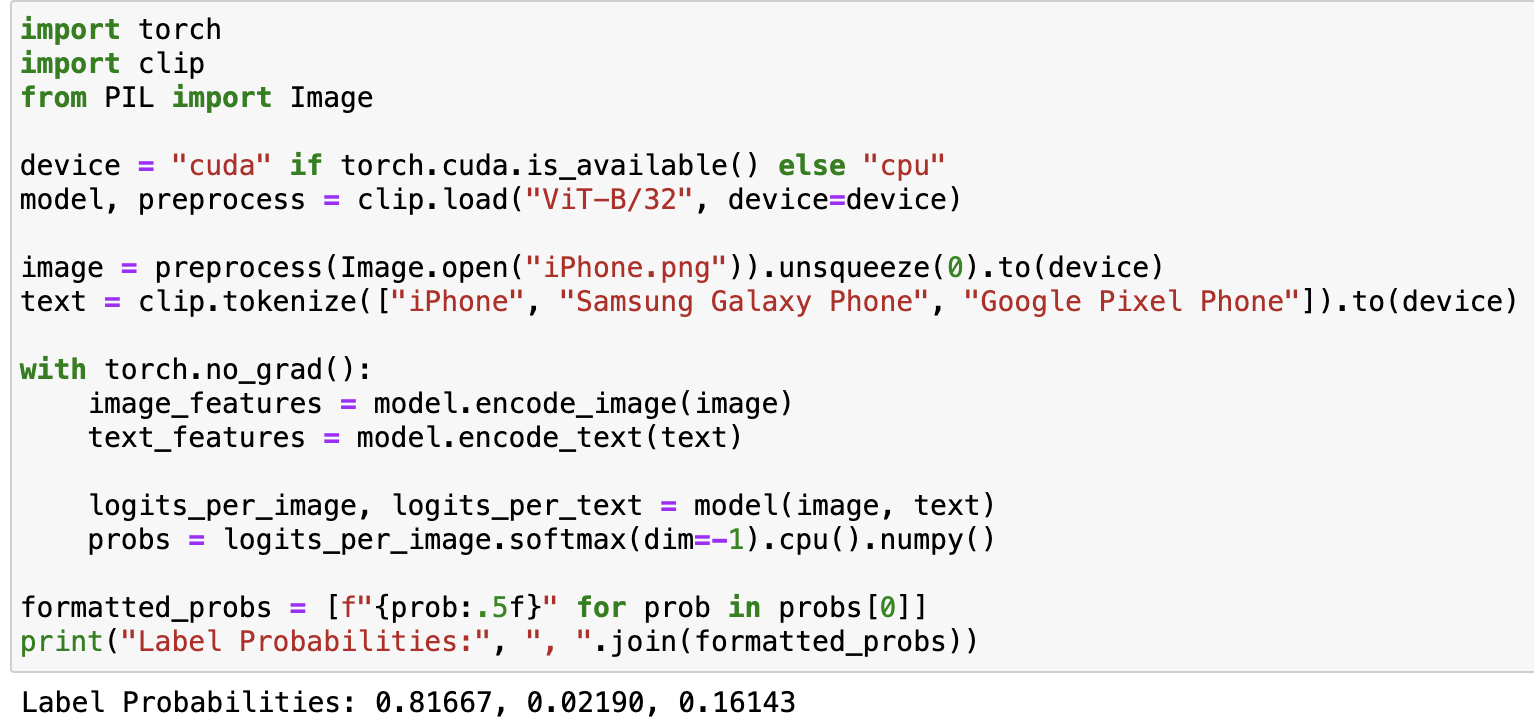

Test #3

We give a new image of an iPhone and the labels “iPhone”, “Samsung Galaxy Phone”, and “Google Pixel Phone” (in this order).

Input image:

More Zero-Shot Prediction Examples

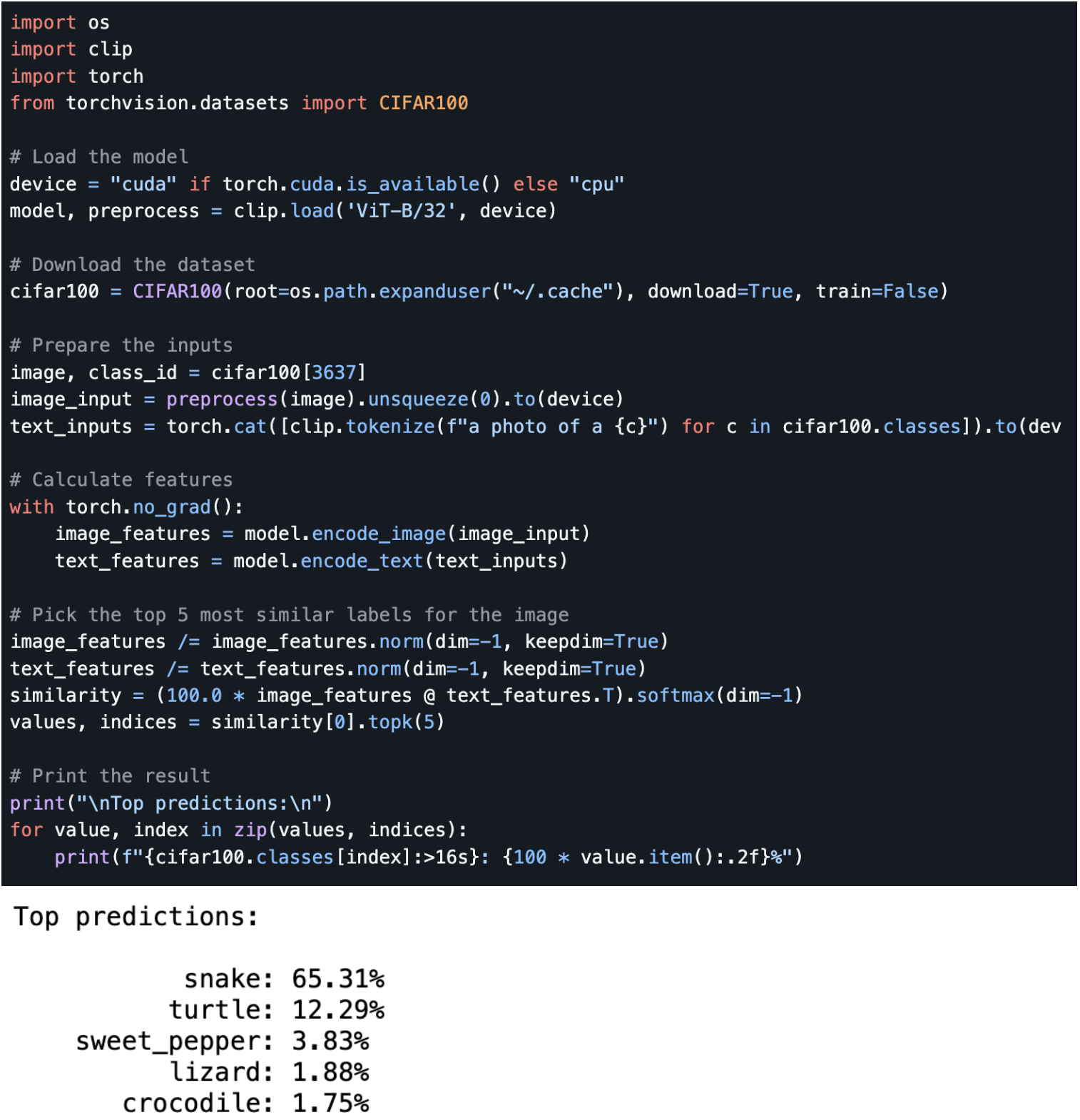

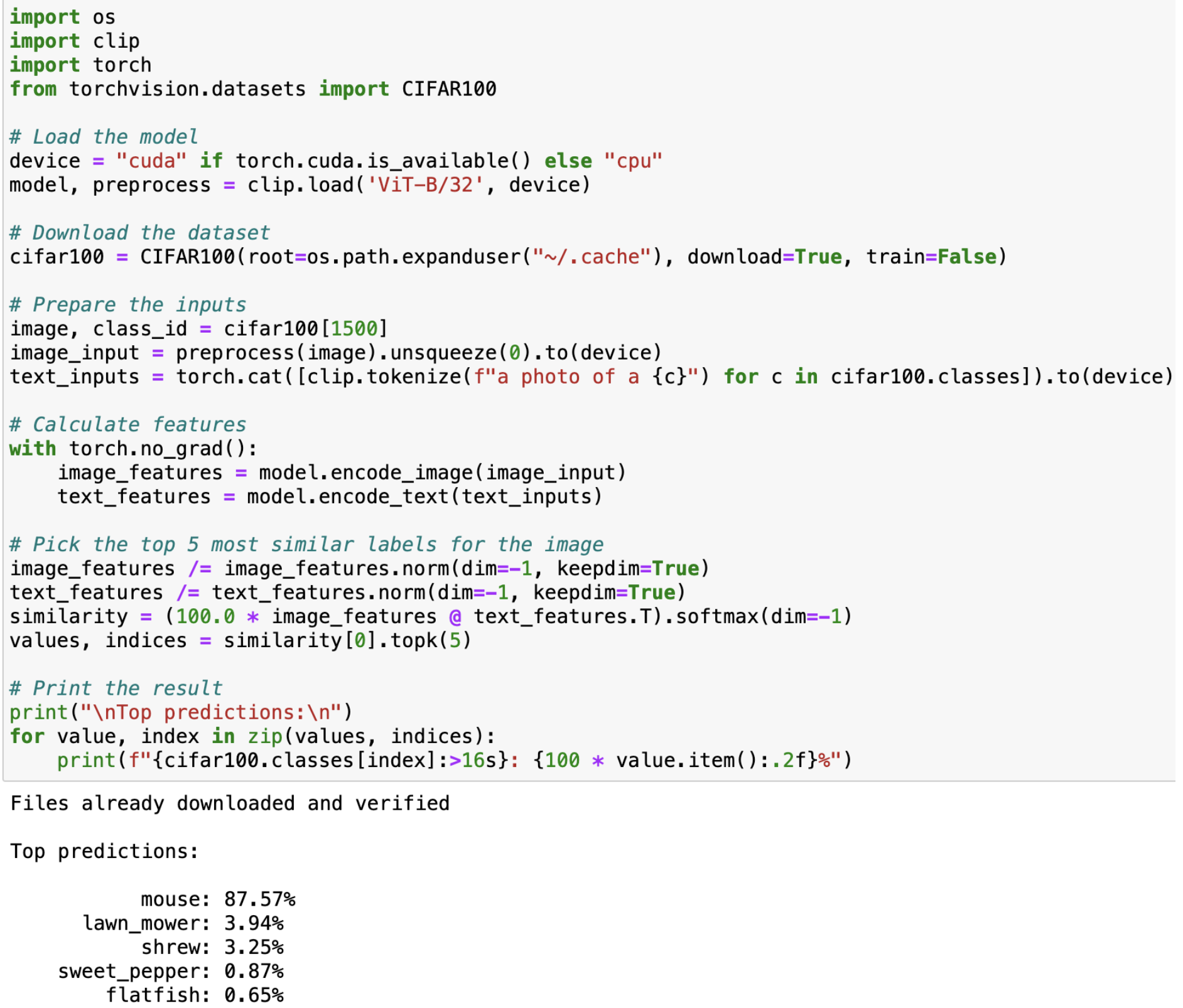

Here we locally reproduce the zero-shot capabilities of CLIP. We take a random image from the CIFAR-100 dataset and predict the top 5 most likely labels among the 100 labels from this dataset.

Test #1

Input image:

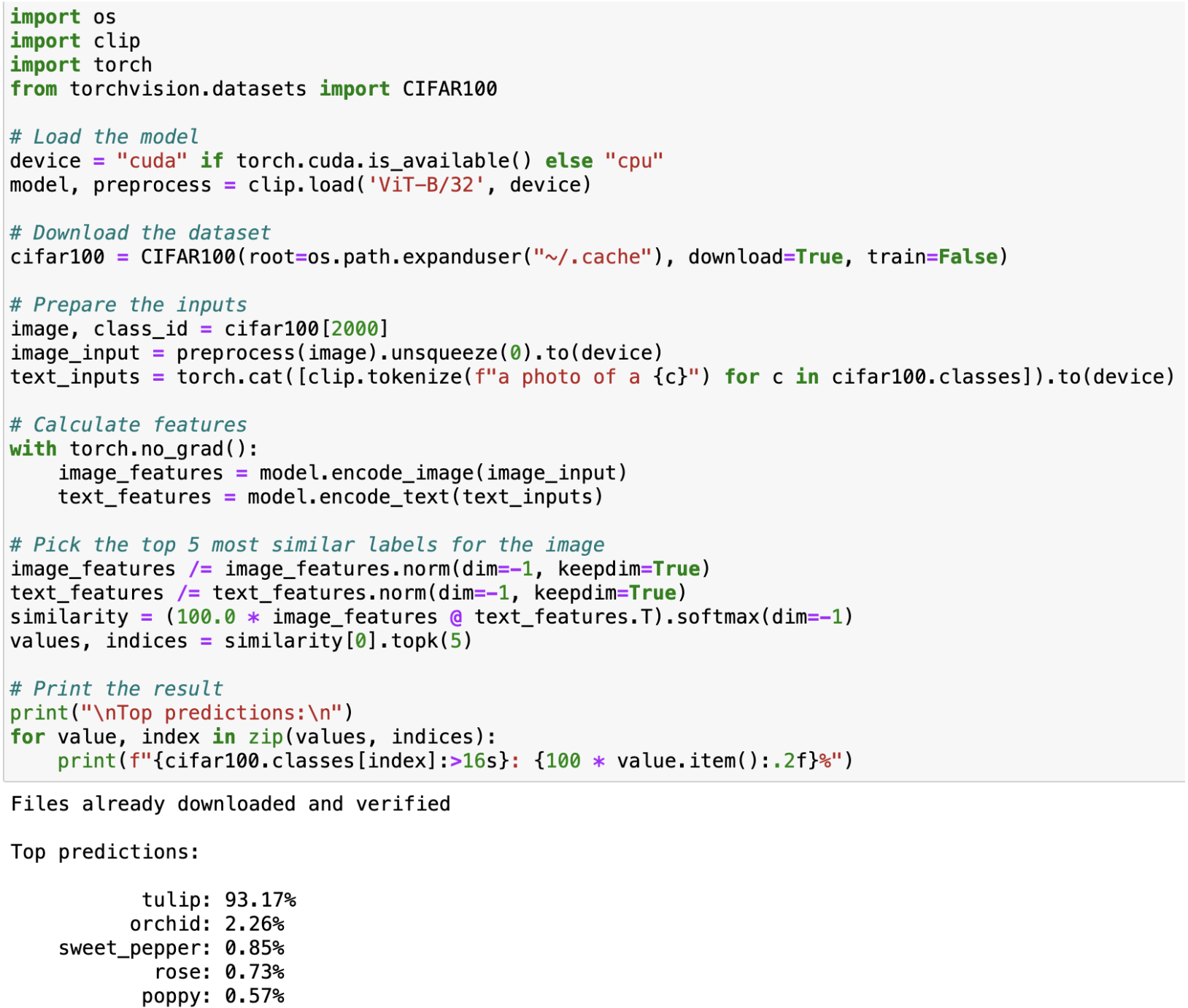

Test #2

Input image:

Test #3

Input image:

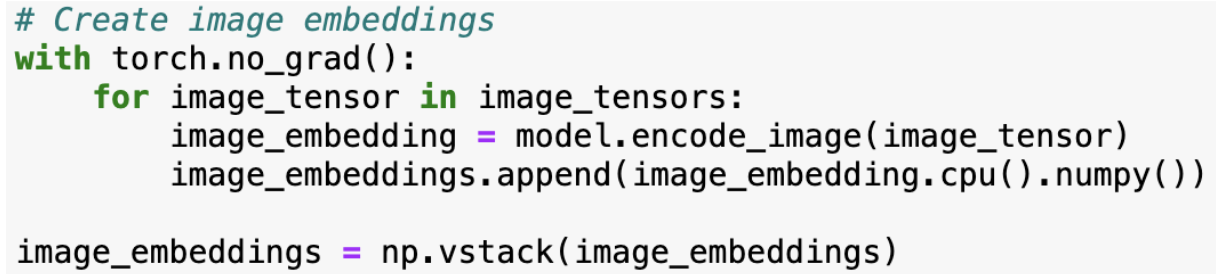

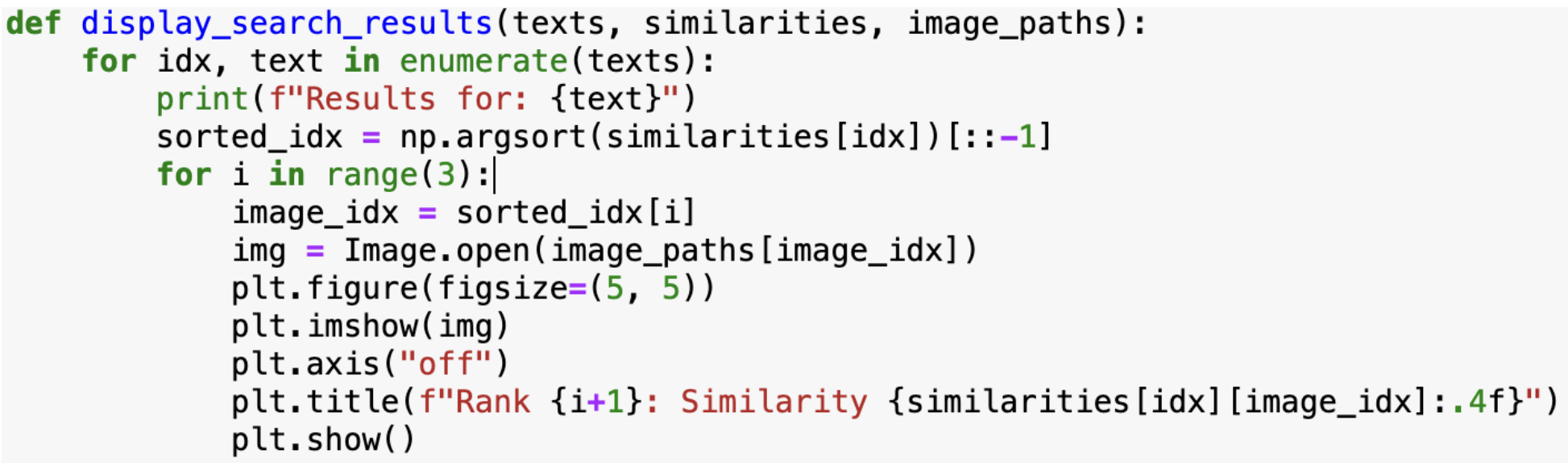

Implementing Our Own Ideas: Text-to-Image Search with CLIP

We implemented a new capability on top of CLIP: text-to-image search. This tool can be used to query for relevant images given some text prompt

First, we load a dataset of images and preprocess these images. Our dataset included images from different categories such as sports, nature, animals, consumer products, etc.

Next, given a dataset of images, we create image embeddings via CLIP’s image encoder.

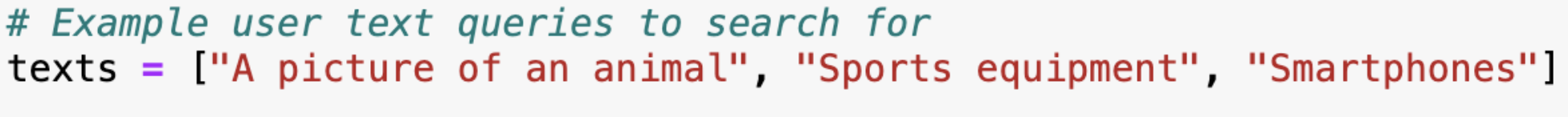

We have a list of example user text queries such as the following:

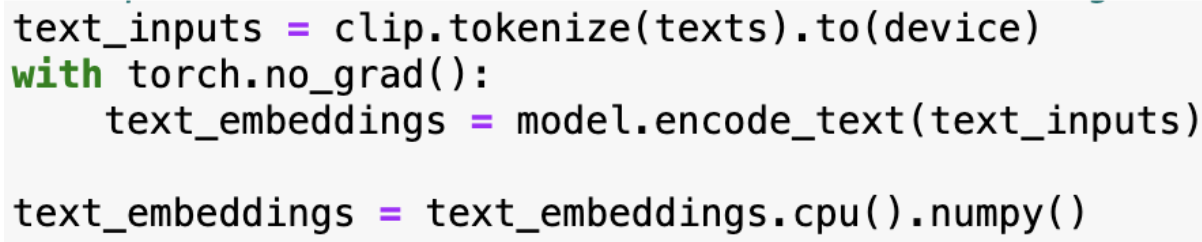

Using this list of text prompts, we use CLIP’s text encoder to create text embeddings in the shared image-text embedding space.

Once we have embedded both the dataset of images and user text queries in this shared embedding space, we can calculate the similarities between a given text prompt and an image using cosine similarity. An image embedding vector and a text vector will have a high cosine similarity if they are related to each other because CLIP embeds both of these in a shared embedding space.

We calculate cosine similarity between text and image embedding vectors with the following:

Finally, we write a function to take the top k most similar images to a given text prompt. We choose k=3 for this example.

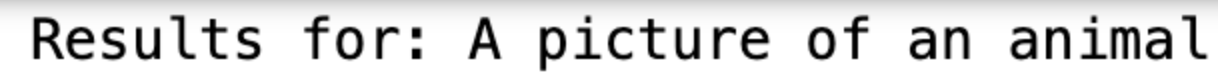

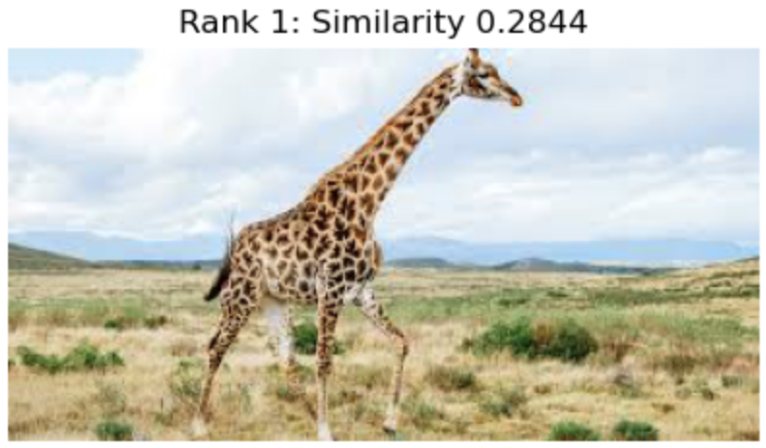

These are the results we get:

![]()

Overall, our implementation of a text-to-image search algorithm using CLIP had overall good results. We think it can be extended to different domains and use cases. For example, if we have a very large dataset of medical scans for different parts of the body, with some extra finetuning, doctors can potentially use this text-to-image search tool to search for these scans with a textual query.

Reference

Please make sure to cite properly in your work, for example:

[1] Radford, A., Kim, J., Hallacy, C., Ramesh, A., Goh, G., Agarwal, S., Sastry, G., Askell, A., Mishkin, P., Clark, J., Krueger, G., & Sutskever, I. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2103.00020

[2] Zhuang, Jiedong, Jiaqi Hu, Lianrui Mu, Rui Hu, Xiaoyu Liang, Jiangnan Ye, and Haoji Hu. (2024). FALIP: Visual Prompt as Foveal Attention Boosts CLIP Zero-Shot Performance. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2407.05578

[3] Frolov, V. (2021, January 14). CLIP from OpenAI: what is it and how you can try it out yourself. Habr. https://habr.com/en/articles/537334/

[4] Hessel, J., Holtzman, A., Forbes, M., Le Bras, R., Choi, Y. (2022). CLIPScore: A Reference-free Evaluation Metric for Image Captioning. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2104.08718

[5] Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, L., & Polosukhin, I. (2017, June 12). Attention Is All You Need. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762

| [6] Pierce, F. (2020, May 17). From A-Z, how a soccer ball reaches a consumer’s doorstep, by Kewill | Procurement. Supply Chain Digital. https://supplychaindigital.com/procurement/z-how-soccer-ball-reaches-consumers-doorstep-kewill |

[7] Refurbished iPhone 13 128GB - Pink (Unlocked) - Apple. (n.d.). Www.apple.com. https://www.apple.com/shop/product/FLMN3LL/A/refurbished-iphone-13-128gb-pink-unlocked

[8] Giraffes: Diet, Habitat, Threats, & Conservation. (n.d.). IFAW. https://www.ifaw.org/uk/animals/giraffes

[9] Wikipedia Contributors. (2018, November 29). Elephant. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elephant

[10] Smith, C. (2019, February 7). Bird Feature: Eastern Bluebird. Nature’s Way Bird Products; Nature’s Way Bird Products. https://www.natureswaybirds.com/blogs/news/bird-feature-bluebird#&gid=1&pid=1

[11] Tennis ball. (2019). Nature’s Workshop Plus. https://www.workshopplus.com/products/tennis-ball

[12] Wikipedia Contributors. (2022, May 23). Basketball (ball). Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basketball_%28ball%29