Introduction to Camera Pose Estimation

Camera pose estimation is one important component in computer vision used for robotics, AR/VR, 3D reconstruction, and more. It involves determining the camera’s 3D position and orientation, also known as the “pose” in various environments and scenes. PoseNet, MeNet, and JOG3R are all various deep learning techniques used to accomplish camera pose estimation. There are also sensor-based tracking like LEDs and particle filters. We focus on geometric methods, specifically Structure-from-Motion (SfM).

- Introduction to Camera Geometry Basics

- Structure-from-Motion Overview

- Methods

- GLOMAP

- Visual Geometry Grounded Deep SfM

- InstantSfM

- Emerging Alternatives Beyond SfM

- Conclusion

- Sources

Introduction to Camera Geometry Basics

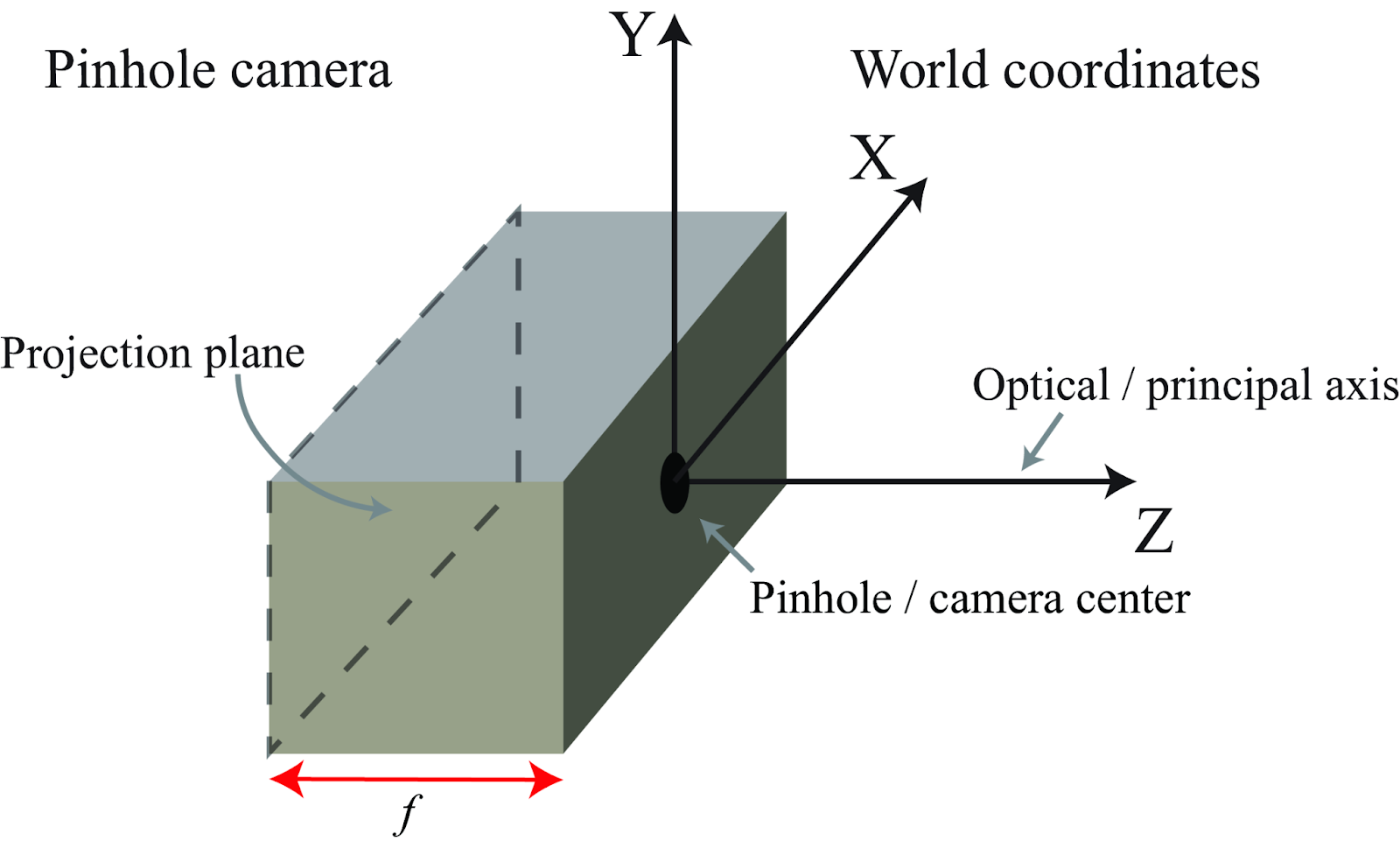

Camera geometry is necessary to map out the relationship between 3D points in the real world and the corresponding 2D projection which are pixel coordinates. There are a few technical terms we will use. First, the process of projecting 3D coordinates to 2D is typically modeled by the Pinhole Camera Model as shown in the figure below. This model describes the mathematical relationship of the projection where the pinhole is the center of projection and the origin of a Euclidean coordinate system and the Z axis is the image plane or focal plane [2.]

Figure 1. Pinhole Camera Model [1]

Second, we define world coordinates as representations of a location in the World Cartesian coordinate system. The 3D position of a point P in this world is set to P = (X, Y, Z). Second, camera coordinates represent the coordinate system in the virtual camera plane. The planes x and y are parallel to the world coordinates axes X and Y but run in opposite directions. The signs of the coordinates will stay the same meaning both images in the world and camera coordinates are identical except for a flip. Assuming the distance from the pinhole to the sensing plane is represented by f also known as the focal length, then we can define the following equations:

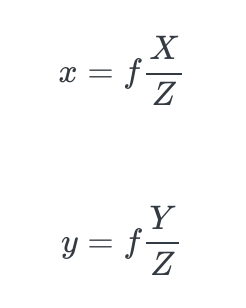

Figure 2. Perspective projection equations [1]

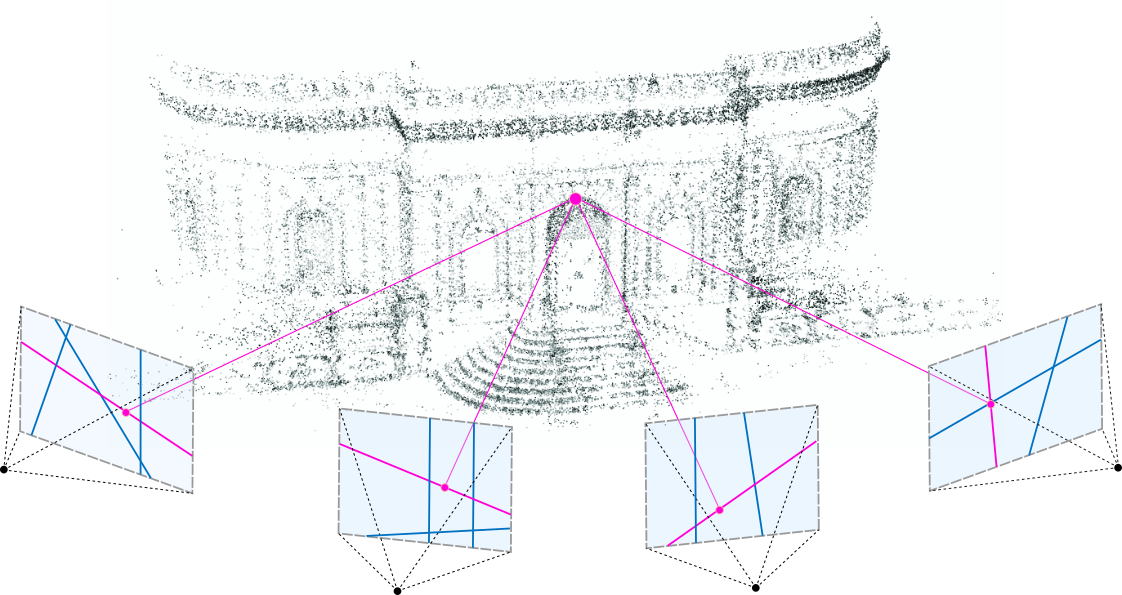

Based on the perspective projection equations which are from the notion of similar triangles, we can map the 3D point [X, Y, Z]T to the coordinates [x, y]T on the image plane. We also add a fourth coordinate to get P = (X, Y, Z, 1)T to get homogeneous coordinates. We can confirm that we get the perspective projection if we multiply P with the matrix K as shown below [2].

Figure 3. Perspective projection of 3D point p [1]

Then we can transform the homogeneous coordinates scaled by the camera’s focal length f to convert it to heterogeneous coordinates and divide by Z into 2D coordinates. As a result, the 2D projected coordinates can be labeled as p.

Structure-from-Motion Overview

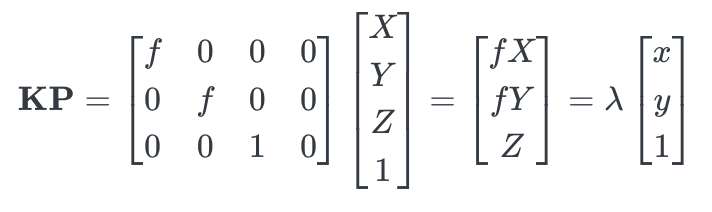

SfM is the geometric method of recovering the 3D structure and camera motion through a collection of images which addresses a fundamental problem in computer vision. SfMs are applied to novel view synthesis which generates images of a specific scene or subject from a certain point of view given that the only available information of the specific scene or subject is images taken from different points of view than the one we are trying to synthesize. SfMs are also used for cloud-based mapping and localization which involves using powerful cloud servers for generating dynamic mappings of surrounding environments often used for autonomous vehicles and robots.

Figure 4. Structure from Motion point cloud [4]

SfM works by analyzing how various points in the images shift and change relative to one another as the camera angle and position changes. This is typically done through motion parallax which reconstructs the scene or subject’s 3D structure and camera orientation and position for each image taken at different point of views. Going more in detail, the first step involves taking multiple overlapping photos to capture either a scene or subject. Photos must be taken in well-lit lighting conditions with all features visible in multiple photos and no reflective surfaces. Then, software processes the photos to distinguish individual features such as textures and corners. Then, the software analyzes the 2D movement of all these features across all the images with the algorithm inferring the camera’s movement and the 3D position of the features. This perception is similar to how humans perceive depth such as how objects closer to the observer moves faster than objects further away move. Finally, the 3D points are reconstructed to build a 3D model that is typically in the form of point clouds [11].

Methods

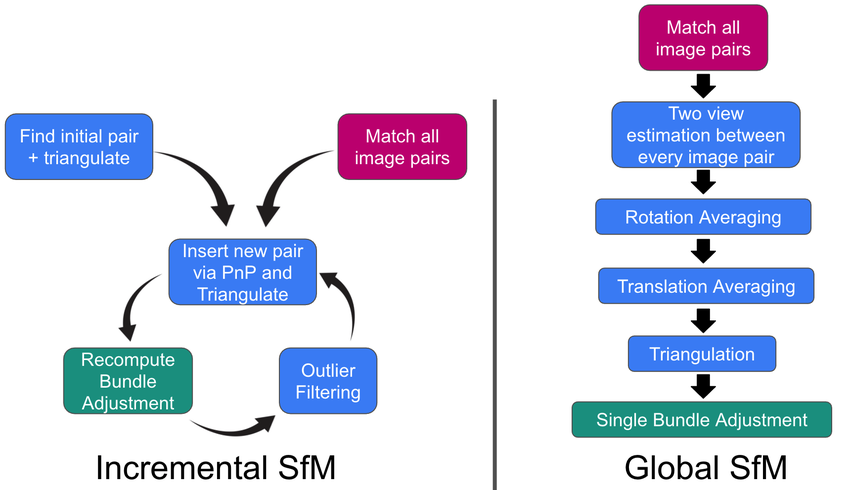

There are two methods of SfM: incremental and global. Incremental SfM starts with a pair of images and creates a 3D model by adding cameras and points step by step to estimate a similar pose of the existing construction. Then, it seeds the pair selection to form an initial reconstruction also known as triangulation. This creates a robust and more accurate model. On the other hand, global SfM considers all images and their relationship with each other to be a single optimization problem and attempts to reconstruct the camera poses and points simultaneously. First there is a feature mapping process for all the images that then builds a view graph. Finally, through various rotation and translation averaging, we get a global optimization and a 3D model. Global SfM is more scalable and efficient for large scale mapping but is not as accurate than incremental nor is it as robust if there are outliers or missing data such as if the graph is not fully connected.

Figure 5. Incremental SfM vs. Global SfM [3]

GLOMAP

GLOMAP Overview

GLOMAP is a recent global SfM system by Pan et al. that addresses challenges encountered in global SfM. At a high level, GLOMAP is a general-purpose pipeline designed to improve the accuracy and robustness of global SfMs while retaining its scalable and efficient characteristics of global SfM. In fact, Pan et. al report that GLOMAP produces on par with or even superior to COLMAP (the incremental gold standard) in accuracy, yet is orders of magnitude faster. For example, on a large-scale dataset LIN from LaMAR of 36,000 images, GLOMAP obtained ~90% correct camera pose recall at 1m error and reconstructed the scene in approximately 5.5 hours, while COLMAP had only ~50% recall and took more than 7 days to process the same data. These results highlight a significant step forward for global SfM methods.

Challenges of Global SfM

The key difficulty in global SfM lies in how it handles noise and outliers when combining all pairwise relations simultaneously. In particular, the global translation averaging step is the main cause of global SfM’s shortfall in robustness. After estimating relative motions between image pairs (the view graph), global SfM does rotational averaging, which estimates all camera orientations from pairwise relative rotation. To obtain consistent global camera positions from noisy pairwise translations, however, is the more challenging problem.

When estimating motion between two images, only the direction of the translation can be recovered and not the distance. This means that every pair of cameras have an unknown scaling factor. This introduces scale ambiguity that requires multiple loops or triplets of views to resolve. Furthermore, if those triplets form “skewed” geometric configurations, the scale estimates become very noise-sensitive. [9]

Another challenge is the global SfM’s heavy dependence on camera intrinsics. This information is needed so that global SfM can decompose two-view geometry into a direction and scale, and if there is any calibration error, the translation direction becomes highly inaccurate. [7]

In scenarios with nearly collinear motion (e.g. walking forward with a front-facing phone, driving down a street, etc.) the geometry does not provide enough information for translation averaging, and this can cause reconstructions to become unreliable. [9]

GLOMAP Contributions

The key innovation introduced by GLOMAP is jointly estimating all camera positions and 3D points, which replaces the translation averaging step. In other words, instead of first computing camera translations in isolation and then triangulating points, GLOMAP merges these into one optimization problem in a step the authors call global positioning. This approach is fundamentally different from prior global SfM systems, which typically did a rotation averaging step, followed by translation averaging, and then triangulation. GLOMAP’s joint global position step replaces the fragile process with one unified optimization that solves for camera positions and 3D points at the same time.

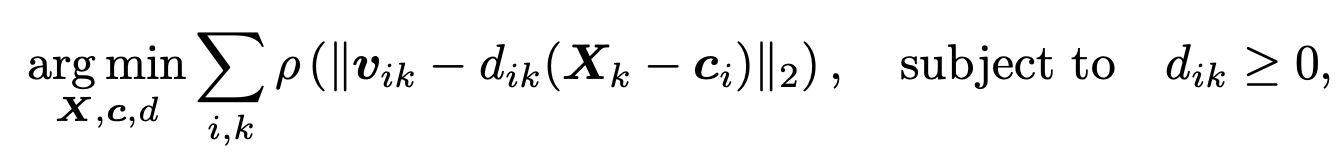

This optimization is achieved by minimizing a robust objective function over all camera centers ci, 3D points Xk, and depth scaling factors dik. Specifically, the method minimizes the misalignment between the observed viewing direction vik, derived from feature tracks and known intrinsics, and the predicted ray from the estimated camera position to the 3D point:

Here, ρ(⋅) is a robust loss function, and the constraint dik ≥ 0 makes sure that the points lie in front of the corresponding cameras, a basic requirement for valid geometry. This formulation removes the need for a separate translation averaging step by treating the scene structure and camera positions as a part of one problem and solving for both the 3D points and camera positions together. As a result, this approach avoids relying on noisy or ambiguous pairwise translations. It uses feature tracks across multiple views to enforce geometric consistency, and this makes it more reliable under real-world conditions like straight-line motion or inaccurate intrinsics.

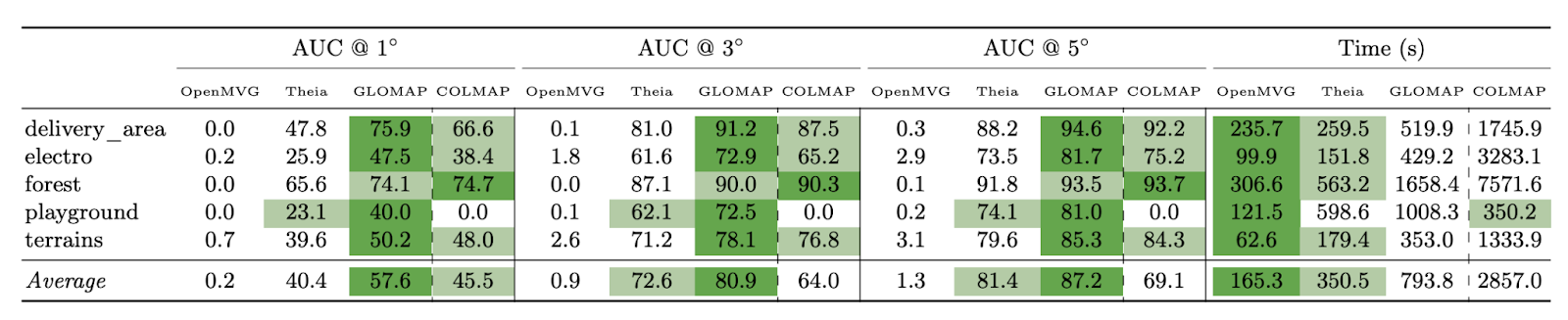

Interestingly, GLOMAP doesn’t require any special initialization for either the 3D points or the camera centers. All positions are initialized randomly within a broad volume, and the optimizer is still able to converge to an accurate solution. In practice, the optimizer is able to reliably converge from random initial values, possibly due to the stability of the bounded angular loss used. This is a major contrast with incremental SfM systems, which usually rely on careful seeding with a strong image pair to get started. To evaluate the effectiveness of GLOMAP, the authors conduct extensive experiments across several benchmark datasets, including ETH3D, LaMAR, IMC 2023, and MIP360. In particular, Figure 6 shows results from the ETH3D MVS (rig) benchmark, comparing GLOMAP against three state-of-the-art SfM systems: OpenMVG, Theia, and COLMAP. GLOMAP achieves the highest average accuracy across all angular thresholds (1°, 3°, and 5°). For example, it obtains an average AUC @ 5° of 87.2, compared to 81.4 for Theia and just 69.1 for COLMAP. Despite its accuracy, GLOMAP remains computationally efficient. It completes reconstructions in an average of 793.8 seconds across the scenes, which is over 3 times faster than COLMAP (2857.0 seconds on average). These results demonstrate GLOMAP’s ability to produce both higher-quality reconstructions and faster runtimes than prior global and incremental methods, and they showcase GLOMAP as a scalable and robust general-purpose SfM system.

Figure 6. Performance of GLOMAP on ETH3D MVS Benchmark [7]

GLOMAP is a significant step forward in balancing accuracy, speed, and robustness in Structure-from-Motion. While traditional systems tend to be strong in one or two of these areas, GLOMAP achieves strong performance across all three. It avoids reliance on carefully selected initialization pairs, handles large-scale reconstructions efficiently, and remains robust under noisy conditions. These characteristics make GLOMAP a practical and adaptable solution for modern SfM tasks.

Visual Geometry Grounded Deep SfM

VGGSfM Overview

VGGSfM is a deep learning-based SfM pipeline designed to be fully differentiable end-to-end. It is conceptually closer to a global SfM approach since it estimates all camera poses jointly, but it avoids the typical weaknesses of classical global SfM such as noise-sensitive averaging of rotations and translations. Instead of relying on separate rotation/translation averaging steps, VGGSfM uses learned neural modules (e.g. Transformers) to recover camera parameters collectively, which helps avoid the instability that traditional global methods can face due to noisy pairwise estimates.

Challenges with Current Incremental SfM Systems

Traditional incremental SfM systems, like COLMAP, build up 3D reconstructions one step at a time starting with a good image pair and then gradually adding new views. While this works well in many cases, it also introduces a number of weaknesses. One main issue is that these systems rely heavily on chaining pairwise keypoint matches into longer feature tracks. Small errors in matching can add up over time, and this leads to a “drift” in the reconstruction, especially on long sequences. The pipeline also consisted of many disconnected steps, like matching, RANSAC filtering, PnP pose estimation, triangulation, and bundle adjustment, which makes it difficult to train or tune the entire system as a whole.

Since most of these steps are not differentiable, there is no way to optimize them end-to-end. Another challenge is that these systems require a strong initialization in order to work properly. Oftentimes, a carefully chosen pair of images with lots of shared features is needed for initialization. If the initial pair is weak or mismatched, the whole reconstruction can fail or break down. Finally, traditional pipelines struggle in scenes with low texture or repetitive patterns, where keypoint detection and matching may become unreliable. In such cases, the system may not be able to find enough consistent matches between images, which prevents it from building the 3D structure.

VGGSfM Contributions

A major innovation in VGGSfM is its approach to correspondence tracking. Traditional SfM pipelines typically rely on chaining two-view matches across image pairs to form multi-view feature tracks. However, this process is prone to error accumulation and drift. VGGSfM replaces this process with a learned 2D point tracking module that operates across the entire image set. Instead of depending on manually designed feature descriptors like SIFT or SuperPoint, it is able to use deep feature extractors and a transformer-based matching module to track points at the pixel level. This results in dense, accurate, and consistent multi-view correspondences, without needing explicit pairwise chaining. Because the point tracking is learned and is end-to-end differentiable, it can adapt during training to improve consistency and coverage, especially in hard conditions like wide baselines or low-texture scenes. The tracker is also able to predict per-point confidence and visibility. This helps the system to focus only on matches that are high quality during reconstruction stages later in the process.

Another major contribution of VGGSfM is how it handles camera pose estimation. Instead of registering cameras one at a time like in incremental SfM or solving for relative orientations and positions in traditional global SfM, VGGSfM uses a transformer model that processes all images and track features and predicts all camera poses simultaneously. This allows the system to reason globally about spatial relationships while avoiding the instability and scale ambiguity that comes with pairwise translation estimation. After pose prediction, VGGSfM initializes 3D points and refines the structure and motion using a differentiable bundle adjustment module. Unlike traditional bundle adjustment, which depends on external solvers like Ceres, VGGSfM includes a version that’s differentiable and built directly into the neural network, the second-order Theseus solver. Because of this, the model can learn to improve earlier steps, like point tracking or camera pose estimation, so that the final optimization is more accurate. By combining steps such as tracking, pose recovery, triangulation, and refinement into one system that can be trained together, VGGSfM builds a more consistent and reliable SfM pipeline compared to traditional approaches.

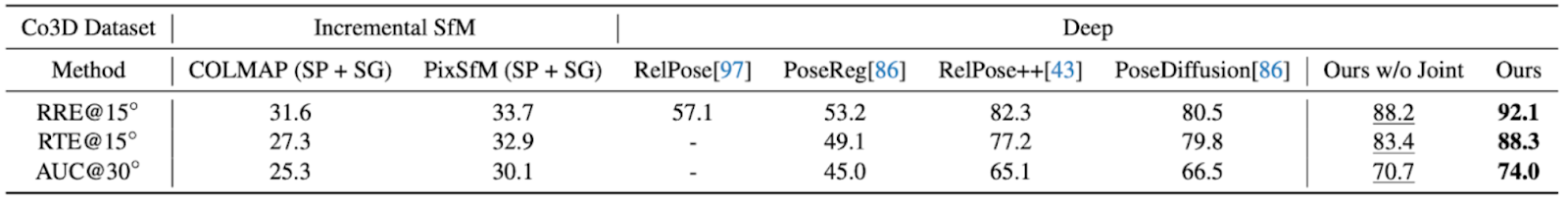

In practice, VGGSfM achieves strong results on the 3D computer vision CO3D dataset. As shown in Table 1, it outperforms other existing SfM methods. VGGSfM reaches an RRE @ 15° of 92.1 and an RTE @ 15° of 88.3, which is significantly ahead of COLMAP (31.6 and 27.3) and PoseDiffusion (80.5 and 79.8). These results are especially notable given the wide baselines in CO3D, which often cause traditional pipelines to fail. Even without joint training, VGGSfM performs well, but training all components together provides the best accuracy overall.

Figure 7. Performance of GLOMAP on ETH3D MVS Benchmark [8]

InstantSfM

InstantSfM Overview

With different SfMs comes with different CPU computational costs that InstantSfM aims to decrease. InstantSfM is a comprehensive system that utilizes a fully sparse and parallel SfM pipeline to improve GPU acceleration in order to achieve significant speedup benefits while preserving performance. This is done through adding additional PyTorch operations that provide native and easy-to-use support directly for users.

Challenges with Current COLMAP and GLOMAP 3D Reconstruction Software

COLMAP and GLOMAP require bundle adjustment (BA) or global positioning (GP) which all increase the computational overhead especially when attempting to scale to handle large data scenarios. This leads to a performance tradeoff in order to gain speed in SfM. Additionally, COLMAP and GLOMAP are implemented in C++ which restrains it from benefitting from different external optimization methods. VGGSfM using feed-forward methods for 3D reconstruction, they are still unable to be scalable. For instance, VGGSfM struggles with thousands of input views inputted simultaneously due to a spike in GPU memory usage.

To address this issue, InstantSfM explores the potential in GPU parallel computation in order to gain significant speedups for each critical stage of the entire SfM pipeline. InstantSfM’s design builds on top of the sparse-aware bundle adjustment optimization which helps improve BA and GP processing. In fact, through the team’s extensive research, they were able to gain 40x speedup for COLMAP performance without sacrificing accuracy and they even saw improvements in the reconstruction accuracy.

InstantSfM Contributions

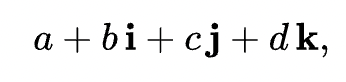

To achieve such GPU acceleration, Zhong et al. developed a comprehensive SfM optimization pipeline in PyTorch that builds a customized Lie group and Lie algebra. They implemented quaternion addition which extends complex numbers typically seen in the form shown below.

Furthermore, they implemented large matrix multiplication operations which were not previously supported by PyTorch. Through their work, InstantSfM provides user-friendly endpoints that allow users to seamlessly integrate it into their work without worrying about the underlying details as they are abstracted away. As a result, InstantSfM is able to tackle the computation bottleneck to provide state-of-the-art accuracy with significant efficiency, allowing SfM technology to be scalable for datasets containing thousands of images.

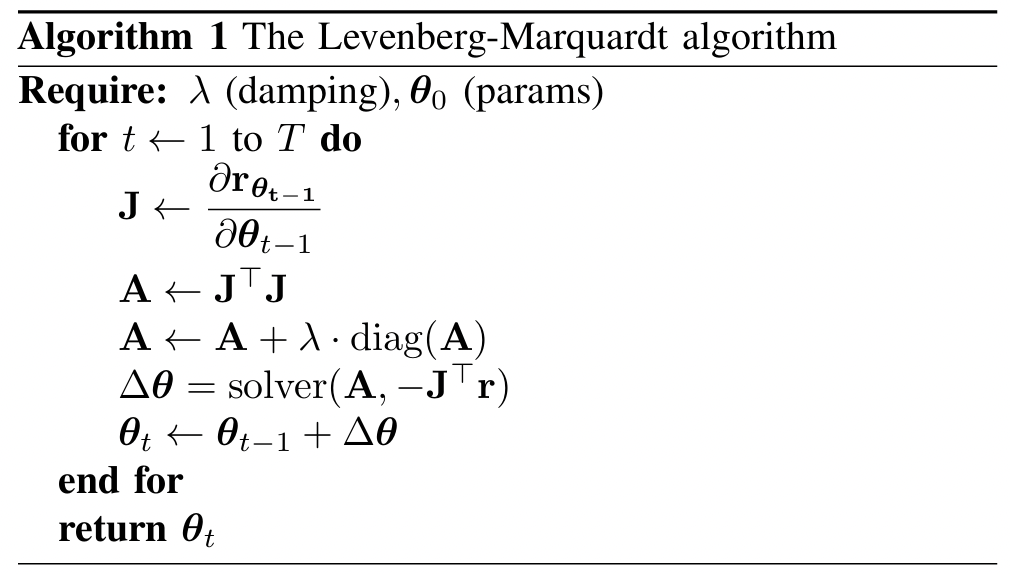

Additionally, the team extended sparse-aware bundle adjustment to GP in PyTorch to provide the latest global SfM system. This allows readjusting and refining the 3D coordinates during reconstruction and improving the estimates of the 3D geometry and camera poses. This is done through minimizing the reprojection error which measures the difference between the observed 2D image coordinates and the projected 2D coordinates estimated from the 3D points and camera parameters. The team utilized the Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm to optimize GP and BA. This algorithm is as follows:

Figure 8. The Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm [12]

This algorithm uses the Jacobian where each row of the matrix contains the gradient of the 2D reprojection with respect to all the parameters. Hence, this matrix is large by nature which restricts it from being utilized by the GPU. InstantSfM was able to extend the sparse data structure to create a unified framework. They extended the standard 2×7 and 2×3 Jacobian blocks to also provide depth constraint terms by implementing special block assembly routines that handle the geometric constraints while ensuring matrix efficiency. Extending spare-aware bundle adjustment allows scalability to run full bundle adjustment operations on large datasets that contain thousands to millions of images within an appropriate timeframe that allows SfM systems to truly scale.

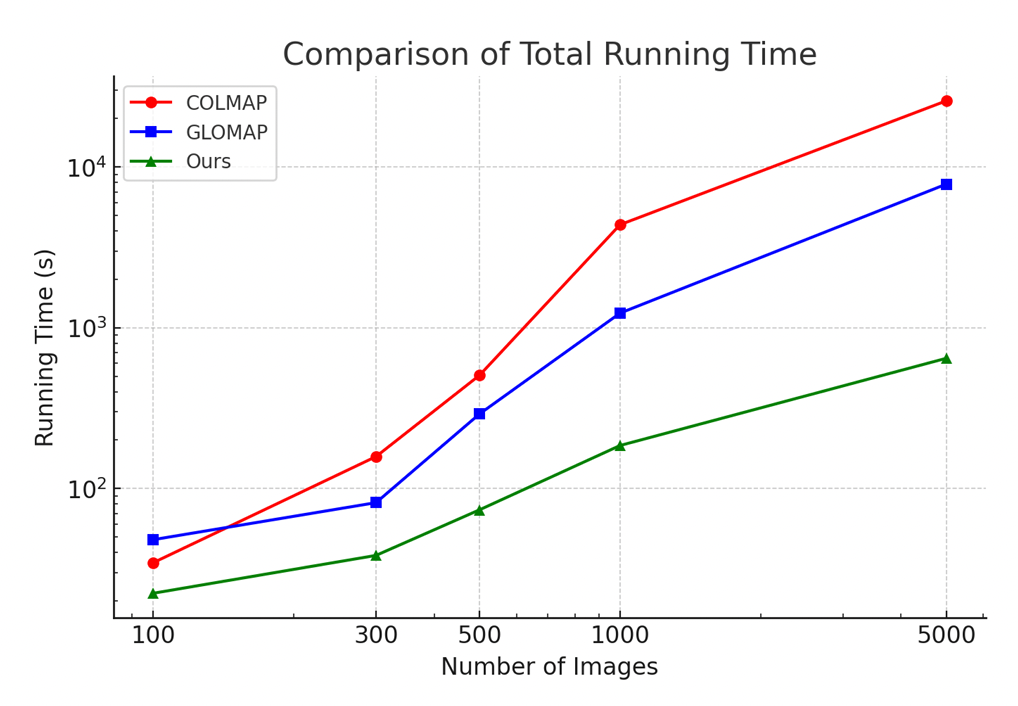

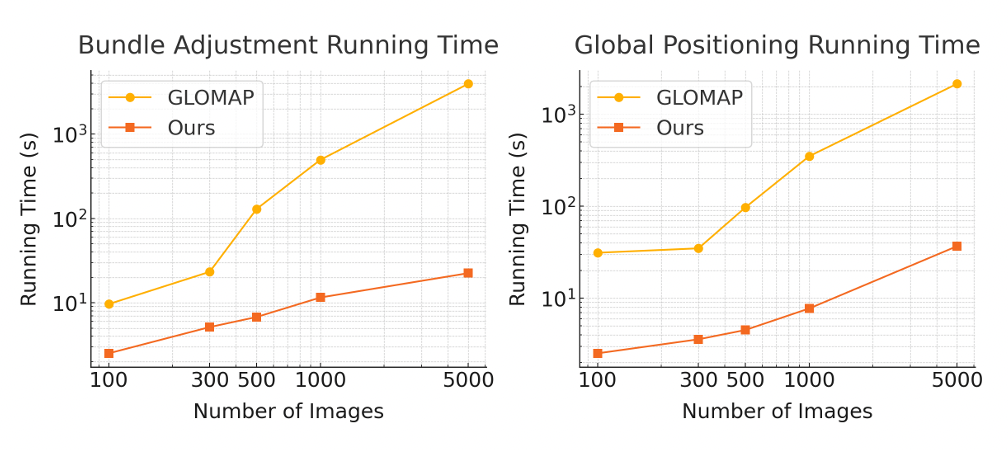

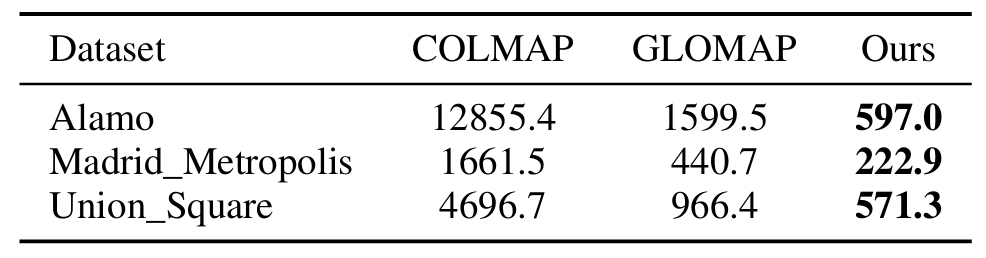

Diving deeper into InstantSfM benefits compared to COLMAP, GLOMAP, and VGGSfM, the team used Nvidia’ H200 GPU to test against camera pose estimation, quality of rendering with 3D Gaussian splitting to develop photorealistic 3D scenes from 2D input like images or video, and accuracy of 3D map reconstruction. Below are graph depicting the speedup seen with InstantSfM.

Figure 9. Comparison of SfM running time among COLMAP, GLOMAP, and InstantSfM [12]

Figure 10. Comparison of GLOMAP vs. InstantSfM on Bundle Adjustment and Global Positioning [12]

From these comparisons, it is evident with the amount of time InstantSfM is able to save. The team tested from input ranging from 100 to 5,000 images taken from the MipNeRF360 dataset. Additionally, there are significant GPU savings

Figure 11. GPU runtime comparison [12]

By leveraging sparsity awareness operations in PyTorch directly, InstantSfM is able to provide a fast and simple user interface. As seen from the GPU runtime comparison table, InstantSfM is able to accomplish significant speedups compared to current existing SfM approaches in improving robustness in these systems and reconstruction quality.

Emerging Alternatives Beyond SfM

With the rapidly developing field of 3D reconstruction, there have also been emerging alternatives beyond SfMs. Some notable examples include Dense Matching-based Pose estimation, DUSt3R, and MASt3R.

Dense Matching–Based Pose Estimation helps tackle human pose estimation problems with learning the dense correlation between RGB images and different human body surfaces. Such technologies are applicable to human action recognition, human body reconstruction, and human pose transfer. Previously, human pose estimation methods were expanded from Mask R-CNN frameworks that handle top-down operation by first conducting object detection to identify the bounding boxes for each person. Then, matching of the dense correspondence is done with each bounding box. These approaches were not robust as they heavily relied on the Mask R-CNN detection with runtime growing worse as the number of humans in the input image increased. With Direct Dense Pose (DDP), it allows significant speedups. It first predicts the instance mask and the global IUV representation and then aggregates them together [10]. Additionally, DDP incorporates a 2D temporal-smoothing scheme to minimize the temporal jitters when processing video input [6].

DUSt3R is a novel system that provides a way for Dense and Unconstrained Stereo 3D Reconstruction of arbitrary image collections to improve geometric 3D vision and make them easier to operate. Previously, multi-view stereo reconstruction (MVS) generated 3D models from many 2D images by identifying corresponding coordinates across many different points of views using depth triangulation and photogrammetry principles. However, the caveat to this was a tedious and cumbersome process. Thus, DUSt3R approaches geometric 3D vision in a different way by operating without prior information about the camera’s positioning and calibration process. DUSt3R is based on Transformer encoders and decoders to express pairwise pointmaps in a unified common reference frame. This differs from traditional SfMs that rely on geometric-based approaches to computer vision tasks.

Lastly, MASt3R tackles problems with image matching, which is a key component to 3D vision performance and algorithms. Although traditionally image matching is considered a 3D problem, it can still be solved through a 2D approach through the utilization of DUSt3R. MASt3R extends pointmap regression to improve the robustness in matching views and coordinates with extreme viewpoint changes. Although there is limited accuracy to what MASt3R can provide, it demonstrates potential in improving image matching to handle a diverse set of viewpoints to handle practical real-life applications. Furthermore, MASt3R solves the quadratic complexity with dense matching that serves as a huge speedup liability if not solved. Through MASt3R, a fast matching scheme is available that outperforms current existing approaches by about 30% [5]. MASt3R also differs from SfM systems by having dense matching and outputting dense 3D point clouds which contrasts against SfMs sparse explicit feature matching approaches and sparse 3D point clouds.

Conclusion

Camera pose estimation plays an important role in creating 3D reconstructions from video and image data, with applications ranging from augmented reality to robotics. Recent developments have introduced new approaches that go beyond the limitations of traditional incremental SfM pipelines. GLOMAP represents a key advance in global SfM by jointly estimating camera positions and 3D options in a single optimization step to address challenges such as scale ambiguity and collinear motion. VGGSfM demonstrates how end-to-end differentiable pipelines can improve the SfM pipeline by making it trainable end-to-end. It uses learned point tracking and jointly estimates all camera poses which helps to reduce drift and improves the performance in challenge scenes (e.g. limited texture information). The approach introduced by VGGSfM shows how combining learning and geometry can lead to improved SfM pipelines. In addition to the developments made by GLOMAP and VGGSfM, InstantSfM offers significant GPU speedups while preserving reconstruction accuracy and also at times improving it. Together, these approaches reflect the growing diversity of SfM methods and the progress made towards making camera pose estimation more accurate and scalable.

Besides SfMs, there are also many approaches that tackle camera pose estimation and derive 3D structures that are fundamentally different from SfMs. Direct Dense Pose, DUSt3R, and MASt3R are all different approaches that differ from the geometry approach SfMs approach computer vision and 3D reconstruction. These various approaches nurture a diverse range of solutions for various problems in computer vision that allow society’s technologies to advance and be robust to handle different use cases.

These various advancements from various types of SfMs to DUSt3R have many applications to the real world such as being critical pieces of technology for self-driving cars, industrial robotics, and mixed reality. Furthermore, with more efficient and highly accurate technology, safety and wellbeing improves. For instance, drones can be equipped with cameras that can rapidly reproduce disaster sites with 3D reconstruction to help rescue teams accurately map out regions for safe entry and identifying structural risks. Furthermore, with 3D reconstruction, humanity as a whole can preserve cultural and heritage sites in the digital space by developing digital twins of historical sites and artifacts, making cultural exploration more accessible to millions of more people. Lastly, 3D reconstruction empowers medical imaging and helps plan out complex procedures with ease by developing 3D models of the human body. The field of 3D reconstruction and camera pose estimation is a promising field with very much practical applications to society to have immense potential in improving all facets of human life.

Sources

- [1] “5 Imaging – Foundations of Computer Vision.” – Foundations of Computer Vision, visionbook.mit.edu/imaging.html#eq-perspctiveProj. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

- [2] “39 Camera Modeling and Calibration – Foundations of Computer Vision.” – Foundations of Computer Vision, visionbook.mit.edu/imaging_geometry.html. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

-

[3] Chen, Jerred. System Diagrams of Incremental vs. Global SFM. Download Scientific Diagram,www.researchgate.net/figure/System-diagrams-of-Incremental-vs-Global-SfM_fig2_364126762. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025. - [4] Joshi, Manish. “Structure from Motion.” LinkedIn, 30 Oct. 2022, www.linkedin.com/pulse/structure-from-motion-manish-joshi/.

- [5] Leroy, Vincent, et al. “Grounding Image Matching in 3D with MAST3R.” arXiv.Org, 14 June 2024, arxiv.org/abs/2406.09756.

- [6] Ma, Liqian, et al. “Direct Dense Pose Estimation.” arXiv.Org, 4 Apr. 2022, arxiv.org/abs/2204.01263.

- [7] Pan, Linfei, Zixin Luo, Zhaopeng Cui, and Marc Pollefeys. “Global Structure-from-Motion Revisited.” Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). 2024.

- [8] Qian, Yiming, Changjian Wang, Yinda Zhang, et al. “Visual Geometry Grounded Structure from Motion.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.04563 (2023).

- [9] Tao, Jianhao, Yuchao Dai, Xinghui Liu, and Hongdong Li. “Revisiting Global Translation Estimation with Feature Tracks.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2024.

- [10] Wang, Shuzhe, et al. “DUST3R: Geometric 3D Vision Made Easy.” arXiv.Org, 2 Dec. 2024, arxiv.org/abs/2312.14132.

- [11] “What Is Structure from Motion?” MATLAB & Simulink, www.mathworks.com/help/vision/ug/what-is-structure-from-motion.html. Accessed 13 Dec. 2025.

- [12] Zhong, Jiankun, et al. “InstantSfM: Fully Sparse and Parallel Structure-from-Motion.” arXiv.Org, 15 Oct. 2025, arxiv.org/abs/2510.13310.