Vision Language Action Models for Robotics

The core of computer vision for robotics is utilizing deep learning to allow robots to perceive, understand, and interact with the physical world. This report explores Vision Language Action (VLA) models that combine visual input, language instruction, and robot actions in end-to-end architectures.

- Introduction

- Background on VLAs

- RT-2 (Google Deepmind)

- OpenVLA (Stanford, UC Berkeley, Toyota Research Institute)

- Octo (UC Berkeley)

- Discussion

- Limitations

- References

Introduction

The core of computer vision for robotics is utilizing deep learning to allow robots to perceive, understand, and interact with the physical world. However, training models to understand the physical world has proven to be extremely difficult, with issues stemming from the lack of training embodied data (robot centric videos, human interactions in tasks). Models also struggle with relating semantic information to the physical world to conduct actions and generalizing or extending to new environments. Vision language action models recently emerged at the forefront of end-to-end models handling visual input, language instruction, and outputting robot actions.

Background on VLAs

Various models typically utilized at most two of these three components: vision, language and action. For example R3M which is a universal visual representation utilizing video and language during training, but only serves as a backbone and relies on training a separate downstream policy for robot action. Another example is Track2Act, which utilizes Vision and Action, with 2D track predictions for trajectories of objects without language/explicit goal set.

Vision Language Action models utilize all 3 in a multimodal pipeline, to concurrently process image/video + language (captions) to output a robot action. Drawing inspiration from transformers, VLA models use a fine tuned vision language model to output actions instead of text answers. In this report, we discuss and compare RT-2 (55B param), OpenVLA (7B param) which use vision language backbones, with Octo, a compact (93M param) generalist robot policy that omits a vision language backbone.

RT-2 (Google Deepmind)

Overview

RT-2 was the first model to indicate success with using pretrained vision language models to directly output robot actions. RT-2 utilized PaLI-X (larger model, overall better performance) and PaLM-E (smaller, performed better on math reasoning) for its backbone. Building on its predecessor, RT-1, which directly trained on robot data, RT-2 draws inspiration from RT-1 on the concept of discretization of action as tokens, demonstrating that robot action can be represented similarly to how VLMs tokenize and process natural language for generation.

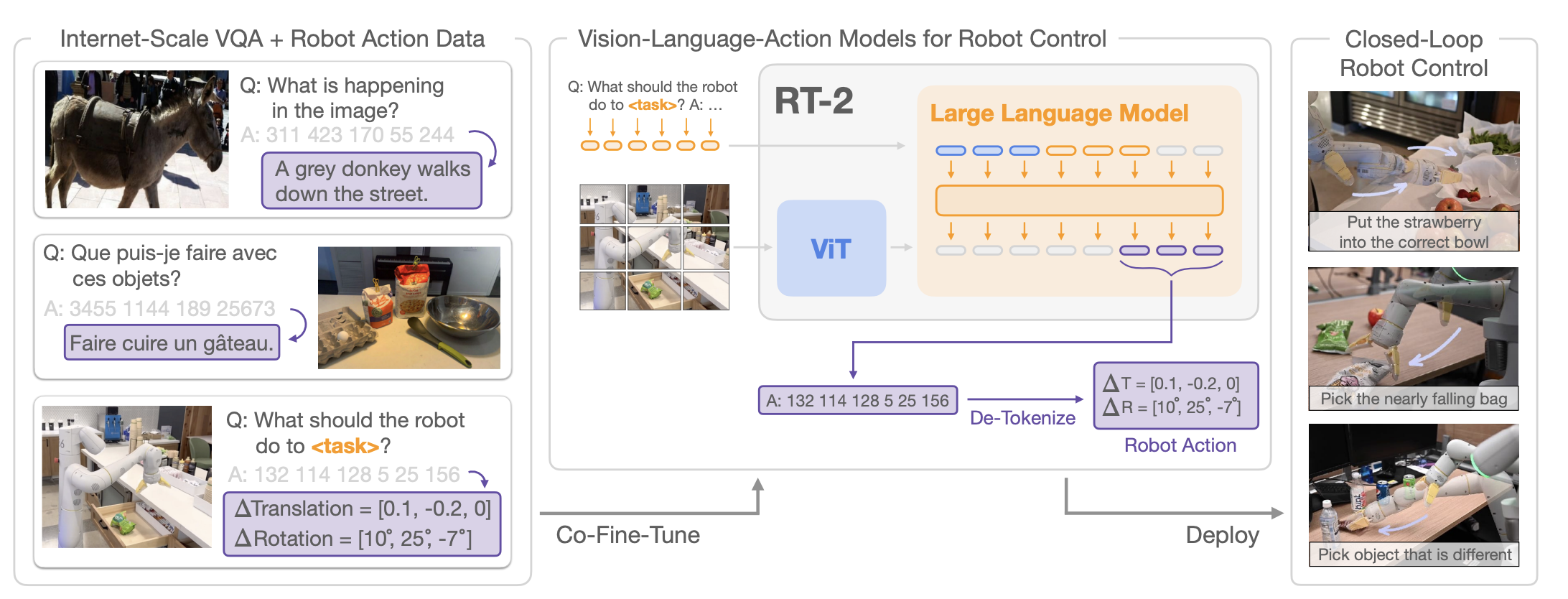

Fig 1. RT-2 Architecture: Vision Language Model adapted for robot action generation.

Architecture

| Component | RT-2-PaLI-X-55B | RT-2-PaLM-E-12B |

|---|---|---|

| Vision Encoder | ViT-22B | ViT-4B |

| Language Model | UL2 (32B encoder-decoder) | PaLM (decoder-only) |

| Total Parameters | 55B | 12B |

Vision Encoder:

Processes robot camera images into patch embeddings (e.g., 16×16 pixel patches) Can accept sequences of n images, producing n × k tokens per image, k is number of patches per image which are passed into a projection layer Pretrained on web-scale image data

Language Model Backbone:

For PaLI-X, the projected image tokens and text tokens are jointly fed into encoder, and the decoder autoregressively generates output For PaLM-E, projected image tokens are concatenated directly with the text tokens, decoder processes the combined stream Pretrained on web-scale vision-language tasks

Tokenization Method and Action Output

Drawing inspiration from discrete representations for action encodings in RT-1, RT-2 represents the range of motion, into 256 distinct steps, otherwise known as bins. The action space consists of 8 dimensions (6 positional, rotational displacement, extension of gripper, command for termination) are discretized into 256 bins uniformly excluding the termination command. These 256 action bins are mapped to existing tokens in the VLM’s token vocabulary. For example “128” could represent a quantity of speed, so when processing an instruction like “put the apple down” the VLM would output a string of 8 discrete tokens per timestep (e.g.”1 128 91 241 5 101 127 217”). This allows the model to be trained using the standard categorical cross-entropy loss used for text generation, without adding new “action heads” or changing the model architecture.

Training for Next Token Generation

Utilized co-fine-tuning strategy where training batches mix original web data along with robot data for more generalizable policies since it exposes the policy to abstract visual concepts from web data and low level robot actions, instead of just robot actions like in RT-1. Vision language data comes from WebLI dataset, consisting of ~10 billion image-text pairs across 109 languages, filtered down to the top 10% (1 billion examples) based on cross-modal similarity.

Robotics data comes from RT-1 dataset (Brohan et al., 2022), which includes demonstration episodes collected on a mobile manipulator. These episodes are annotated with natural language instructions covering seven core skills: “Pick Object,” “Move Object Near Object,” “Place Object Upright,” “Knock Object Over,” “Open Drawer,” “Close Drawer,” and “Place Object into Receptacle”.

Training Configuration

| Parameter | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Loss Function | Categorical Cross-Entropy (Next Token Prediction) |

| Optimization | Gradient Descent (Backpropagation) |

| Learning Rate | 1e-3 (PaLI-X), 4e-4 (PaLM-E) |

| Batch Size | 2048 (PaLI-X), 512 (PaLM-E) |

| Gradient Steps | 80K (PaLI-X), 1M (PalM-E) |

OpenVLA (Stanford, UC Berkeley, Toyota Research Institute)

Overview

OpenVLA is an open-source alternative to RT-2, employs the same architectural structure, utilizing a VLM backbone repurposed to handle action tokens, but at a smaller scale. However, notable differences include training purely on the Open-X-Embodiment dataset which contains 1.3M robot trajectories, utilizing a duel vision encoder structure to capture spatial features. OpenVLA also explores fine-tuning strategies for it’s components unlike RT-2, which kept the backbone pretrained weights frozen.

Architecture

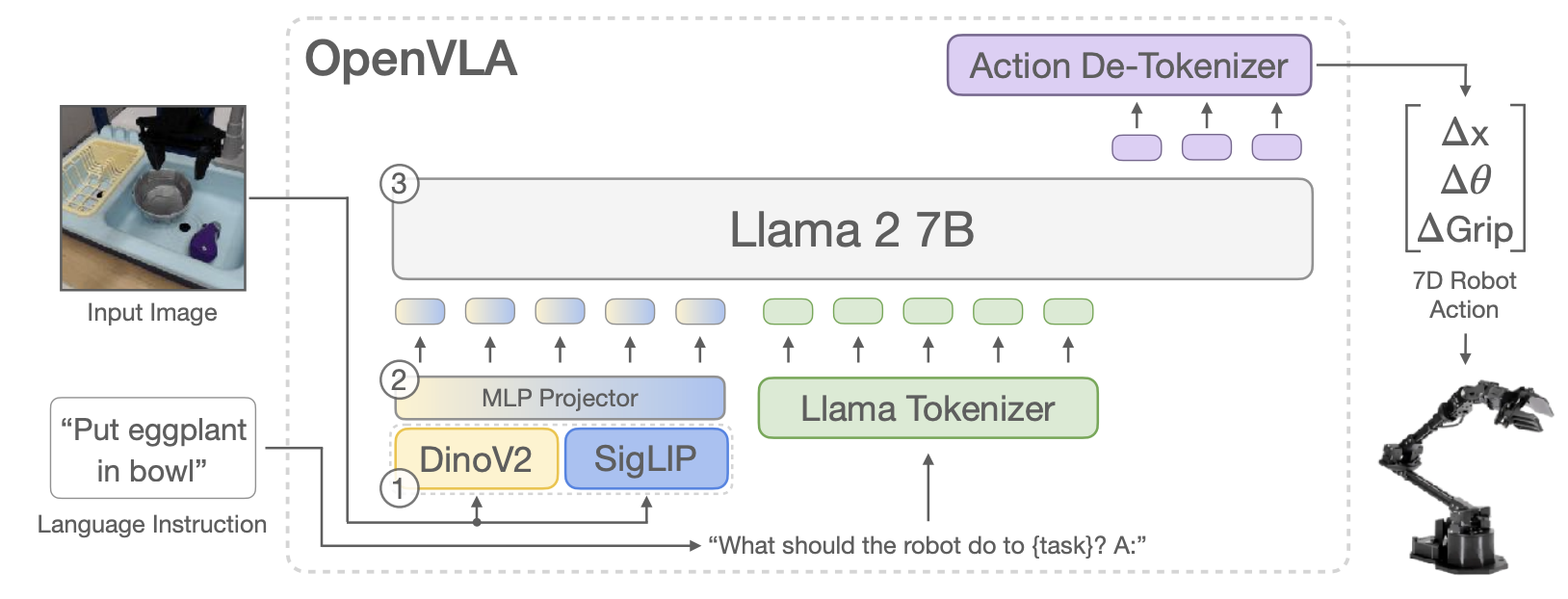

OpenVLA uses a dual-encoder vision system combined with a large language model backbone to process visual inputs and generate robot actions.

Fig 2. OpenVLA Architecture: Dual vision encoders with Llama 2 backbone for action generation.

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| Vision Encoders | DINOv2 (ViT-L/14) + SigLIP (So400m) |

| Projector | 2-layer MLP |

| Language Model | Llama 2 (7B) |

| Total Parameters | ~7B |

Dual Vision Encoders:

- DINOv2 (ViT-L/14): Self-supervised encoder for low-level spatial and geometric features (“where things are”)

- SigLIP (So400m): Contrastive vision-language encoder for high-level semantic understanding (“what things are”)

- Features from both encoders are concatenated channel-wise to create a rich visual representation

- Both encoders pretrained on web-scale data

Projector:

- 2-layer MLP

- Maps fused visual features into the language model’s embedding space

Language Model Backbone:

- Llama 2 (7B parameters, decoder-only)

- Processes concatenated visual tokens and text instruction tokens

- Generates action tokens autoregressively

- Pretrained on web-scale text data

Action Representation

OpenVLA adopts RT-2’s “action-as-language” strategy of discretizing dimensions of robot actions into 256 bins. Since Llama’s tokenizer only reserves 100 “special” tokens, the authors chose to override the 256 least used tokens in the vocabulary for simplicity.

Dedicated Action Tokens:

- Each token represents a discrete bin of continuous motion, preventing semantic interference between “language words” and “action words”

- Quantization: Same 256-bin uniform discretization per action dimension as RT-2

- Output Format: Generates action tokens that are decoded back to continuous values

Training

Dataset:

970,000 trajectories from Open X-Embodiment dataset

Data Curation:

Carefully filtered for high-quality subsets, removing idle actions and low-quality demonstrations to improve training efficiency and model performance.

Training Details:

- Fixed learning rate: 2e-5

- AdamW optimizer with gradient descent (backpropagation)

- Significantly more epochs (27) compared to typical VLMs (1-2 epochs)

- Compute: 64 A100 GPUs for approximately 14 days

Authors attributed increases in performance to fine-tuning the vision encoder, which captures more fine-grained spatial details about scenes for precise robotic control. Another notable change was utilizing 27 epochs at the final vision language model seeing improvement at each iteration, when in the past, vision language models typically trained on 1-2 epochs through the entire dataset.

Training Configuration:

| Parameter | Configuration |

|---|---|

| Loss Function | Categorical Cross-Entropy (Next Token Prediction) |

| Optimization | Gradient Descent (Backpropagation) |

| Learning Rate | 2e-5 (fixed) |

| Epochs | 27 |

| Compute | 64 A100 GPUs (~14 days) |

Octo (UC Berkeley)

Overview

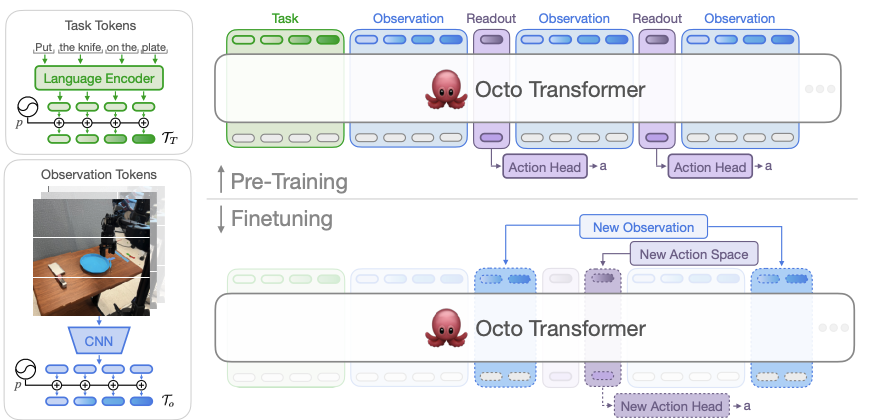

Octo is an open-source Generalist Robot Policy with a fundamentally different approach from VLAs like RT-2. Rather than adapting a massive pretrained VLM, Octo is trained from scratch as a compact transformer designed specifically for robot action. Octo aims to address the flaws of large robot policies trained on diverse datasets such as constrained downstream policies (e.g. restrictive inputs from single camera view) and serve as a “true” general robot policy, allowing different camera configurations, different robots, language vs goal images, and new robot setups.

Fig 3. Octo Architecture: Compact transformer with diffusion-based action decoder.

Architecture

Octo features a custom transformer architecture with modular input-output mechanisms:

| Component | Octo-Small | Octo-Base |

|---|---|---|

| Transformer Parameters | 27M | 93M |

| Vision Encoder | ViT-Small (CNN Stem) | ViT-Small (CNN Stem) |

| Language Encoder | T5-Base (frozen) | T5-Base (frozen) |

| Action Head | Diffusion | Diffusion |

Vision Encoder:

- Transformer Backbone (ViT-Style) with a lightweight CNN Stem (SmallStem16) for tokenization

- Processes images into patch embeddings

- Supports multiple camera views (e.g., third-person and wrist cameras)

- Trained from scratch on robot trajectories

Language Encoder:

- Frozen T5-Base model (111M parameters)

- Encodes natural language instructions into embeddings

- Language conditioning is optional as Octo can also accept goal images

Transformer Backbone:

- Custom transformer (27M for Small, 93M for Base)

- Processes concatenated vision and language tokens

- Block-wise Attention Masking: Handles missing modalities (e.g., robots without wrist cameras) by masking specific input groups during training

- Trained from scratch on robot data (no web pretraining)

Diffusion Action Head:

- Replaces the language modeling head with a diffusion decoder

- Outputs continuous actions rather than discrete tokens

- Iteratively denoises Gaussian noise into precise action trajectories

Action Representation

Octo converts language instructions ℓ, goals g, and observation sequences o₁,…,oₕ into tokens [Tₗ, Tᵧ, Tₒ] using modality-specific tokenizers which are processed by the transformer backbone and fed into a readout head to output desired actions. The block-wise masking forces tokens to attend to tokens from same or earlier timesteps, and tokens corresponding to non-existing observations are completely masked to handle missing modalities. Unlike RT-2 and OpenVLA which discretize actions into tokens, Octo outputs continuous actions via diffusion, utilizing denoising for action decoding for the prediction of action “chunks” ( e.g., chunk of 4 timesteps).

Training

Unlike RT-2 and OpenVLA which fine-tune massive pretrained VLMs, Octo is trained entirely from scratch on robot data. This design choice trades web-scale semantic knowledge for:

- Faster training (14 hours vs. days/weeks for VLAs)

- Smaller compute requirements (single TPUv4-128 podvs. multi-pod setups)

- Full control over the learned representations

Dataset:

800,000 trajectories from Open X-Embodiment dataset covering 9 distinct robot embodiments

Training Details:

- AdamW optimizer, inverse square root learning rate decay

- Weight decay 0.1, gradient clipping 1.0

- 300k steps, batch size 2048 on TPUv4-128 (~14 hours)

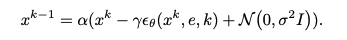

Diffusion denoising process for action generation

The action head is trained with the standard denoising objective loss function:

\[\mathcal{L}(\theta) = \mathbb{E}_{t, x_0, \epsilon} \left[ \|\epsilon - \epsilon_\theta(x_t, t)\|^2 \right]\]This trains the model to predict the noise \(\epsilon\) added to clean actions \(x_0\), enabling iterative denoising at inference time. The diffusion formulation for action generation is:

\[X^{k+1} = \alpha X^k - \gamma \epsilon_\theta(X^k, e) + \sigma z\]where \(X^k\) is the result of the previous denoised stage of the action, \(k\) is the current denoising step, \(e\) is the output embedding from the transformer, and \(\alpha\), \(\gamma\), \(\sigma\) are hyperparameters for the noise schedule.

Why Diffusion Over Alternatives:

Simple MSE was also tried but didn’t perform as well since it incentivizes the robot to an “average” behavior, and can’t handle uncertainty or scenarios with multiple correct choices. Likewise, with discretization/cross-entropy, the robot was observed with less precision, moving to the nearest predefined bin. Diffusion treats actions as continuous values to retain precision and force the denoising process into a specific valid action.

Discussion

| Aspect | RT-2-X (55B) | OpenVLA (7B) | Octo (93M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | 55B | 7B | 93M (Base) |

| Architecture | VLM (PaLI-X) | VLM (Llama 2) | Transformer (Scratch) |

| Vision Encoder | ViT-22B (Pre-trained) | SigLIP + DINOv2 (Fused) | CNN + Transformer (Scratch) |

| Action Output | Discrete (256 bins) | Discrete (256 bins) | Continuous (Diffusion) |

| Training Data | 130k Robot + Web | 970k Robot (OXE) | 800k Robot (OXE) |

| Open Source | No | Yes | Yes |

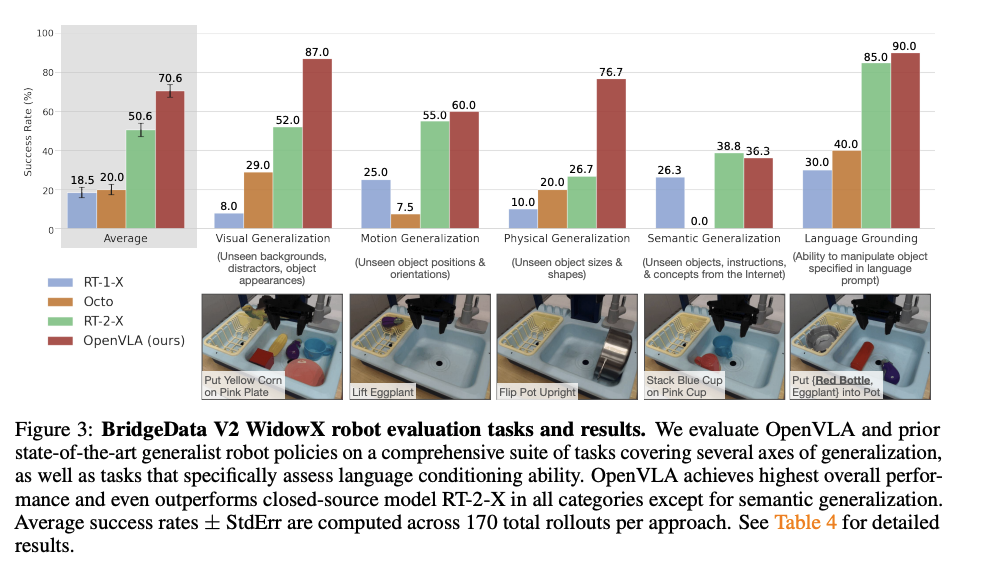

| Overall Success Rate (tasks on WidowX Robot) | 50.6% | 70.6% | 20.0% |

| Key Strength | Semantic Generalization | Physical Generalization | Inference Speed / Motion |

Performance vs Scale

The comparison of 3 models with various different parameter counts demonstrates that scaling parameter count alone doesn’t necessarily determine model performance the most, as architectural decisions and fine-tuning, and other strategies still play an important role. For leveled comparisons, since RT-2 is significantly larger and trained on a different dataset, comparisons are made against the RT-2-X model (trained on 350k trajectories in Open-X-Embodiment) so all 3 models use the same dataset. For example, in OpenVLA fine-tuning the weights in vision encoder portion and uses much more epochs, whereas RT-2 keeps the frozen weights in vision encoder, and although undisclosed, likely used significantly less epochs due to model size, yet Open-VLA on overall performed 20% better than RT-2-X. Another factor that could be considered between these two models was OpenVLA’s data curation strategy from the Open-X-Embodiment compared to RT-2’s co-mixing of robot and web scale data.

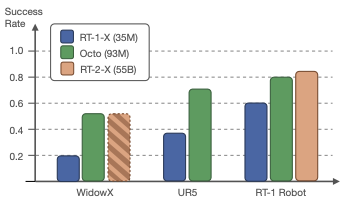

Out-of-the-Box-Evals.

Discrete Tokens for Actions vs Continous Diffusion

The decision represents a tradeoff primarily between high-level semantic reasoning with a large vision language model backbone and precise low-level control with a diffusion policy. Octo was also evaluated using goal image conditioning and found it had 25% higher success rate than when being evaluated with language conditioning.

Comparisons between Octo and other models.

Since RT-2-X is closed-source comparisons required a hybrid approach where RT-2-X metrics were directly sourced from literature, Octo’s authors collabed with Google Deepmind to run Octo on the RT-1 robot. Another factor is the evaluated tasks were seen during pre-training, which likely explains the strong performance here compared to RT-2-X compared to the out-of-the-box evaluations shown earlier. Regardless, Octo still demonstrates the ability of flexibility running on various different robots, as well as it’s efficiency with 93M params compared to 55B in RT-2-X.

Accessibility

A key distinction between these models is accessibility. RT-2 remains closed-source with no public weights, training code, or fine-tuning support—limiting its use to Google’s internal research. On the other hand, OpenVLA and Octo released full model weights, training pipelines, and fine-tuning scripts with public github repositories. OpenVLA additionally supports LoRA fine-tuning on consumer GPUs (single RTX 4090) and 4-bit quantization for deployment, reducing the barrier to entry for robotics researchers without datacenter-scale compute.

Limitations

For RT-2, despite incorporating web-scale data along with its robot data, it is still unable to learn any new motions and is limited to skills seen in the robot data, rather learning new ways to apply those skills. Computations in real-time inference can become a bottleneck due to the sheer size of the model and requires direct integration with TPU-specific hardware.

For OpenVLA, the authors discuss only being able to process single-image input, despite most modern robots having multiple camera views so surrounding spatial awareness is actually limited despite having Dinov2 as an additional image encoder. Inference time was another cited issue especially in high-frequency setups, same as RT-2. Both RT-2 and OpenVLA also share the issue of quantization error for extremely fine-grained and precise movements that can’t be represented in the 256 bins.

For Octo, the authors attributed issues to fine tuning due to the characteristics of training data, performing better in specific camera views despite being general purpose. As illustrated earlier, another limitation was it’s lack of semantioc reasoning capabilities that come from web-scale pretrained VLMs, greatly affecting its performance on language conditioned policy compared to goal conditioned policy.

Some shared limitations include all three models primarily being evaluated on tabletop manipulation with 7-DoF arms, but generalizations to other robot embodiments remains unexplored, (humanoids, quadrupeds, mobile manipulators)

References

[1] Kim, Moo Jin, et al. “OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.09246 (2024).

[2] Octo Model Team, et al. “Octo: An Open-Source Generalist Robot Policy.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.12213 (2024).

[3] Brohan, Anthony, et al. “RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Control.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.15818 (2023).

[4] Sapkota, Ranjan, et al. “Vision-Language-Action Models: Concepts, Progress, Applications and Challenges.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.04769 (2025).