Representation and Prediction for Generalizable Robot Control

Vision-based learning has become a central paradigm for enabling robots to operate in complex, unstructured environments. Rather than relying on hand-engineered perception pipelines or task-specific supervision, recent work increasingly leverages large-scale video data to learn transferable visual representations and predictive models for control. This survey reviews a sequence of recent approaches that illustrate this progression: learning control directly from video demonstrations, pretraining universal visual representations, incorporating predictive dynamics through visual point tracking, and augmenting learning with synthetic visual data. Together, these works highlight how representation learning and prediction from video are enabling increasingly generalizable robot manipulation capabilities.

- Introduction

- Video Learning

- Generalizable Visual Representations

- Context Expansion

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgements

- Reference

Introduction

Vision has become a primary interface through which robots perceive, reason, and act in the physical world. As robots leave structured factory floors and enter human environments, hand-engineered perception pipelines and narrowly specified rewards increasingly fail to scale. Recent research instead treats video as a unifying supervision signal, leveraging its richness to learn perception, dynamics, and control jointly or modularly.

This post surveys a sequence of representative approaches that illustrate this trajectory. We begin with methods that directly convert human videos into executable robot behaviors, then move toward approaches that decouple perception from control through reusable visual representations. We conclude by examining predictive, object-centric models that anticipate future scene evolution. Together, these works outline a shift toward generalizable, context-aware robot control grounded in visual experience.

Video Learning

A natural starting point for learning robot behavior from vision is direct imitation from video. Rather than decomposing perception and control into separate modules, recent work investigates whether robots can acquire complex, environment-aware skills simply by observing humans act in the world. VideoMimic represents a strong instantiation of this paradigm, demonstrating that monocular human videos can be converted into transferable, context-aware humanoid control policies.

Real-to-Sim-to-Real from Monocular Video

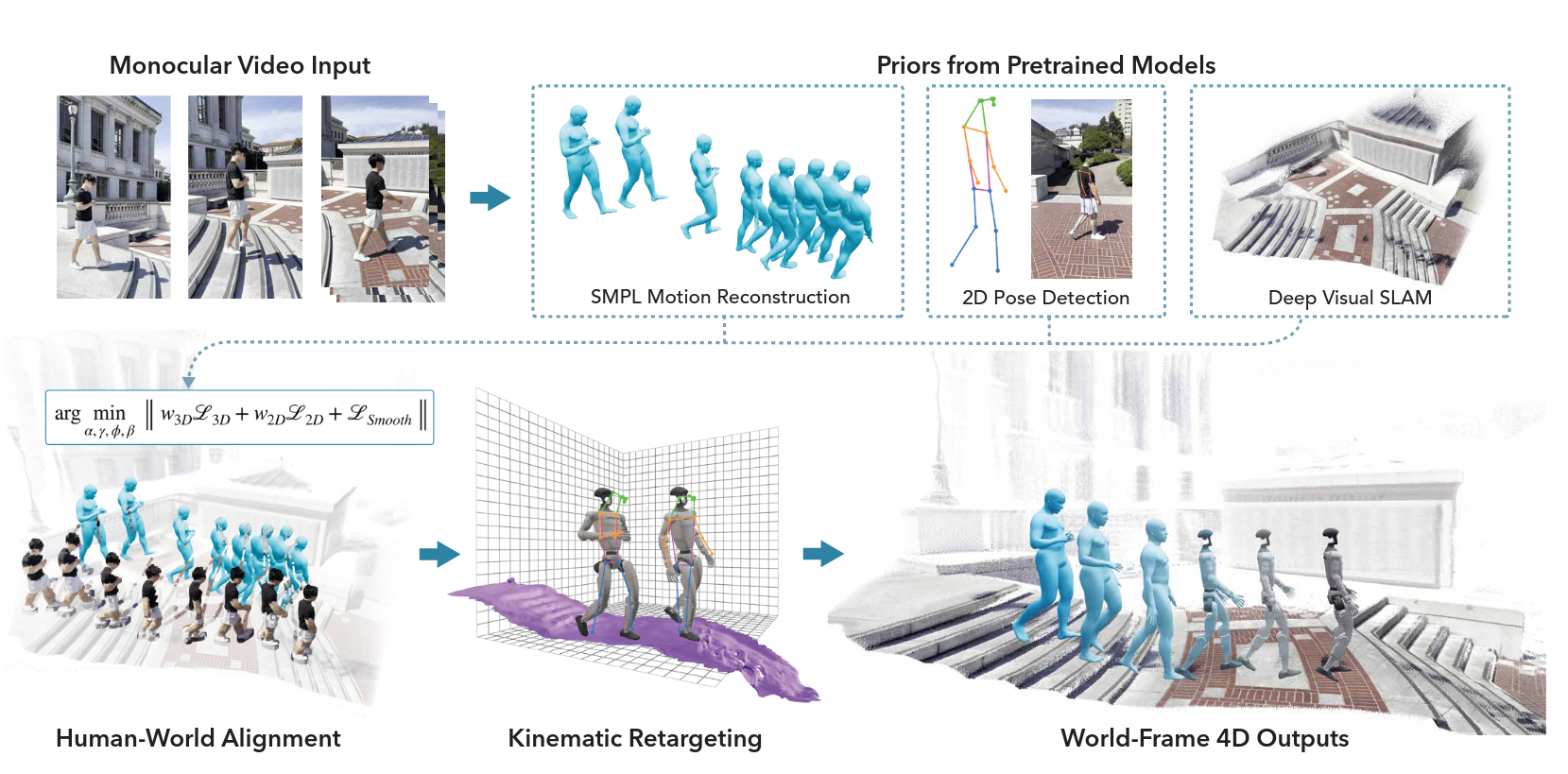

VideoMimic introduces a real-to-sim-to-real pipeline that transforms casually recorded RGB videos into whole-body control policies for humanoid robots. Given a monocular video, the system jointly reconstructs 4D human motion and static scene geometry in a common world frame. Unlike earlier approaches that reconstruct only the person or assume simplified environments, VideoMimic explicitly recovers both the human trajectory and the surrounding physical context, such as stairs, furniture, or uneven terrain, at metric scale.

This joint reconstruction enables downstream learning to reason about environment-conditioned behavior, rather than memorizing isolated motion patterns.

Joint Human–Scene Reconstruction

Given an input video, VideoMimic estimates per-frame human pose using a parametric body model and reconstructs scene geometry via monocular structure-from-motion. The key challenge is metric alignment: monocular reconstructions are inherently scale-ambiguous.

VideoMimic resolves this by jointly optimizing human motion and scene scale using a human-height prior. Let

- \(\gamma_t\) denote the global human translation at time \(t\),

- \(\phi_t\) the global orientation,

- \(\theta_t\) the local joint angles,

- and \(\alpha\) the global scene scale.

The optimization objective is:

\[\min_{\alpha, \gamma_{1:T}, \phi_{1:T}, \theta_{1:T}} \; w_{3D} \mathcal{L}_{3D} + w_{2D} \mathcal{L}_{2D} + \mathcal{L}_{\text{smooth}}\]where:

- \(\mathcal{L}_{3D}\) enforces consistency between reconstructed and lifted 3D joints,

- \(\mathcal{L}_{2D}\) penalizes reprojection error in image space,

- \(\mathcal{L}_{\text{smooth}}\) regularizes temporal motion jitter.

This optimization yields world-frame human trajectories and gravity-aligned scene meshes suitable for physics simulation.

Fig. 1. VideoMimic real-to-sim-to-real pipeline. Monocular videos are reconstructed into human motion and scene geometry, retargeted to a humanoid, and used to train a single context-aware control policy. [1]

Motion Retargeting and Physics-Aware Imitation

The reconstructed human motion is retargeted to a humanoid robot under kinematic and physical constraints, including joint limits, collision avoidance, and foot-contact consistency. These retargeted trajectories serve as reference motions for reinforcement learning in simulation.

Policy learning follows a DeepMimic-style formulation, where the robot tracks reference motion while respecting physics. The reward is defined entirely through data-driven tracking terms, avoiding handcrafted task rewards:

\[r_t = w_p \| p_t - p_t^{*} \| + w_q \| q_t - q_t^{*} \| + w_{\dot{q}} \| \dot{q}_t - \dot{q}_t^{*} \| + w_c \, \mathbb{I}_{\text{contact}} - w_a \| a_t - a_{t-1} \|\]where starred quantities denote reference motion targets. An action-rate penalty discourages exploiting simulator artifacts and promotes physically plausible behavior.

To improve stability, policies are pretrained on motion-capture data, then fine-tuned on reconstructed video motions, mitigating noise and embodiment mismatch.

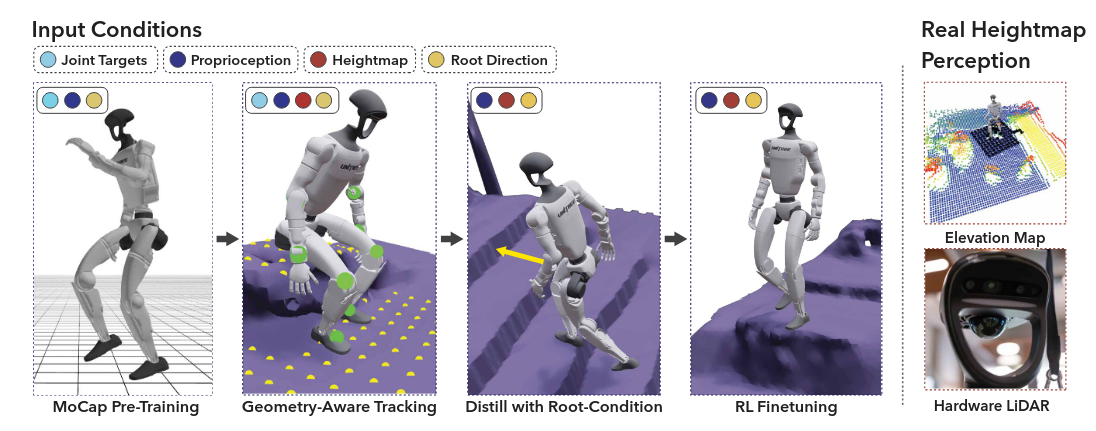

Context-Aware Control via Policy Distillation

A central contribution of VideoMimic is the distillation of multiple motion-specific policies into a single unified controller. After imitation training, the policy is distilled using DAgger into a form that no longer depends on target joint angles.

At test time, the controller observes only:

- Proprioceptive state,

- A local \(11 \times 11\) height-map centered on the torso,

- A desired root direction in the robot’s local frame.

Formally, the deployed policy is:

\[\pi(a_t \mid s_t, h_t, d_t)\]where \(s_t\) is proprioception, \(h_t\) is the terrain height-map, and \(d_t\) is the root-direction command. This enables the robot to autonomously select behaviors like walking, climbing, sitting purely from environmental context, without explicit task labels or skill switching.

Fig. 2. Scene-conditioned imitation learning and policy distillation. [1]

Generalizable Visual Representations

While VideoMimic shows that robots can learn context-aware control directly from reconstructed video demonstrations, its policies remain closely tied to the specific motions and environments observed during training. A complementary direction asks whether vision can be separated from control by learning reusable visual representations that transfer efficiently across tasks, robots, and environments.

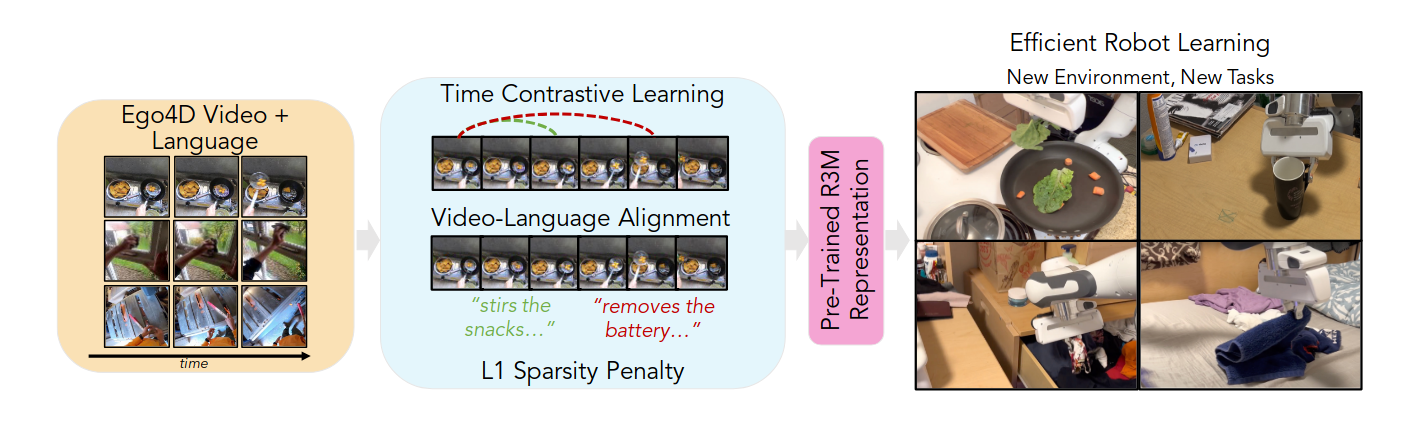

R3M (Reusable Representations for Robotic Manipulation) represents a clean instantiation of this idea. Rather than learning actions, rewards, or dynamics, R3M focuses exclusively on perception. It learns a frozen visual embedding from large-scale human video that can be reused across downstream robot learning problems. This separation of representation learning from control enables strong generalization while remaining easy to integrate into standard imitation or reinforcement learning pipelines.

Fig. 3. R3M pre-training pipeline. Visual representations are learned from large-scale egocentric human video using temporal and semantic objectives, then reused as frozen perception modules for downstream robot manipulation. [2]

Problem Setup

R3M assumes access to a dataset of human videos paired with natural language descriptions. Each video consists of RGB frames

\[[I_0, I_1, \dots I_T]\]and an associated text annotation describing the activity. The goal is to learn a single image encoder

\[F_\phi : I \to z\]that maps an image \(I\) to a continuous embedding \(z\). After pre-training, \(F_\phi\) is frozen and reused across downstream tasks. Robot policies consume the visual embedding concatenated with proprioceptive state rather than raw pixels.

This formulation intentionally isolates representation learning from control and dynamics.

Learning Objectives

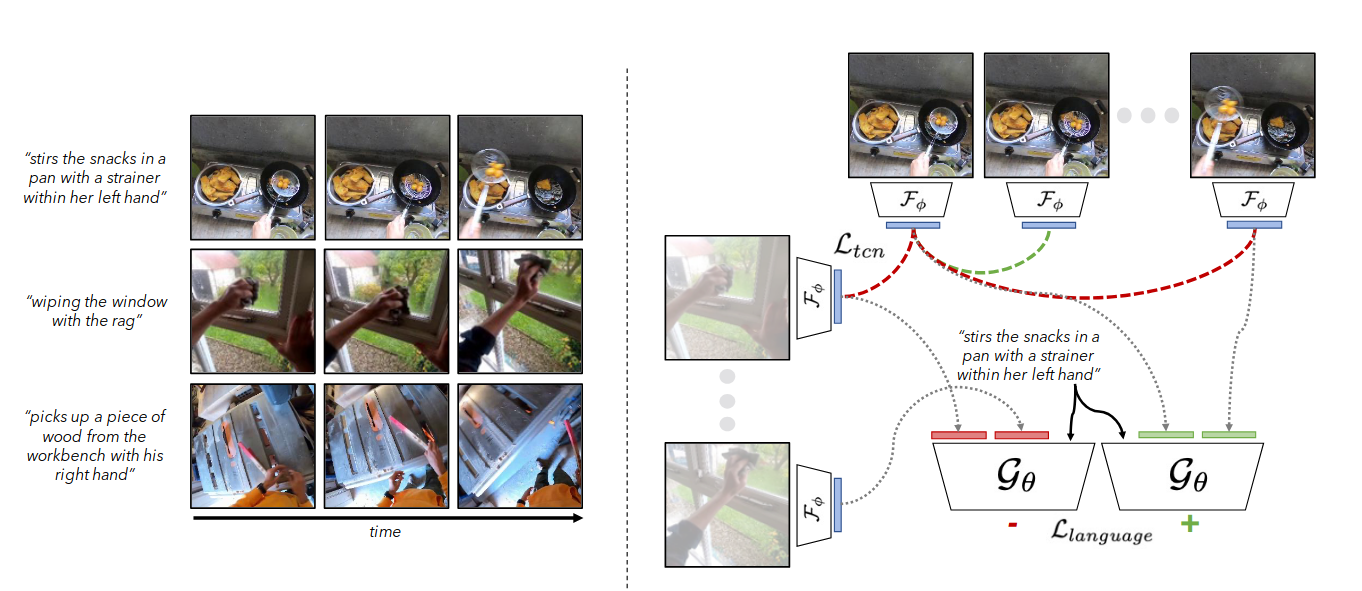

R3M is trained on Ego4D, a large-scale egocentric video dataset covering diverse everyday activities. The representation is optimized using three complementary objectives that target properties useful for robotic manipulation.

Temporal Contrastive Learning

To encourage the representation to encode scene dynamics rather than static appearance, R3M uses time-contrastive learning. Frames close in time are encouraged to map to nearby embeddings, while temporally distant frames or frames from different videos are pushed apart.

The temporal contrastive loss has the following formulation:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{TCN}} = - \sum_{b \in \mathcal{B}} \log \frac{\exp(S(z_i^b, z_j^b))} {\exp(S(z_i^b, z_j^b)) + \exp(S(z_i^b, z_k^b)) + \exp(S(z_i^b, z_{i'}))}\]where \(z = F_\phi(I)\), indices \(i, j, k\) correspond to frames with increasing temporal distance, \(z_{i'}\) is a negative sample from a different video, and \(S(\cdot,\cdot)\) denotes similarity computed via negative L2 distance.

This objective biases the embedding toward encoding how scenes evolve over time.

Video–Language Alignment

Temporal structure alone is insufficient. A useful representation must focus on semantically meaningful elements such as objects, interactions, and task-relevant state changes. R3M therefore aligns visual embeddings with natural language descriptions.

Given an initial frame \(I_0\), a future frame \(I_t\), and a language instruction \(l\), a scoring function \(G_\theta\) predicts whether the transition from \(I_0\) to \(I_t\) completes the described activity. Training uses a contrastive objective:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{Lang}} = - \sum_{b \in \mathcal{B}} \log \frac{\exp(G_\theta(z_0^b, z_t^b, l^b))} {\exp(G_\theta(z_0^b, z_t^b, l^b)) + \exp(G_\theta(z_0^b, z_i^b, l^b)) + \exp(G_\theta(z_0', z_t', l^b))}\]This objective encourages embeddings to capture objects and relations referenced by language, which are directly relevant to manipulation.

Fig. 4. R3M pretraining. R3M is trained on Ego4D video–language pairs using temporal contrastive learning and video–language alignment to produce semantically grounded, temporally coherent visual embeddings for robotic manipulation. [2]

Sparsity and Compactness

R3M additionally encourages compact embeddings through explicit regularization. Sparse representations reduce sensitivity to background clutter and improve robustness in low-data imitation settings.

This is enforced via L1 and L2 penalties:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{Reg}} = \lambda_3 \| z \|_1 + \lambda_4 \| z \|_2\]Full Training Objective

The complete pre-training objective combines all components:

\[\mathcal{L}(\phi, \theta) = \mathbb{E}_{I \sim \mathcal{D}} \left[ \lambda_1 \mathcal{L}_{\text{TCN}} + \lambda_2 \mathcal{L}_{\text{Lang}} + \lambda_3 \|F_\phi(I)\|_1 + \lambda_4 \|F_\phi(I)\|_2 \right]\]The encoder \(F_\phi\) is implemented as a ResNet backbone and trained on Ego4D. After training, the encoder is frozen and reused without further adaptation.

Downstream Policy Learning

For downstream tasks, R3M embeddings are concatenated with robot proprioceptive state and used as input to a policy trained via behavior cloning:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{BC}} = \| a_t - \pi([z_t, p_t]) \|_2^2\]where \(z_t = F_\phi(I_t)\) and \(p_t\) denotes proprioceptive features.

Empirical Results and Implications

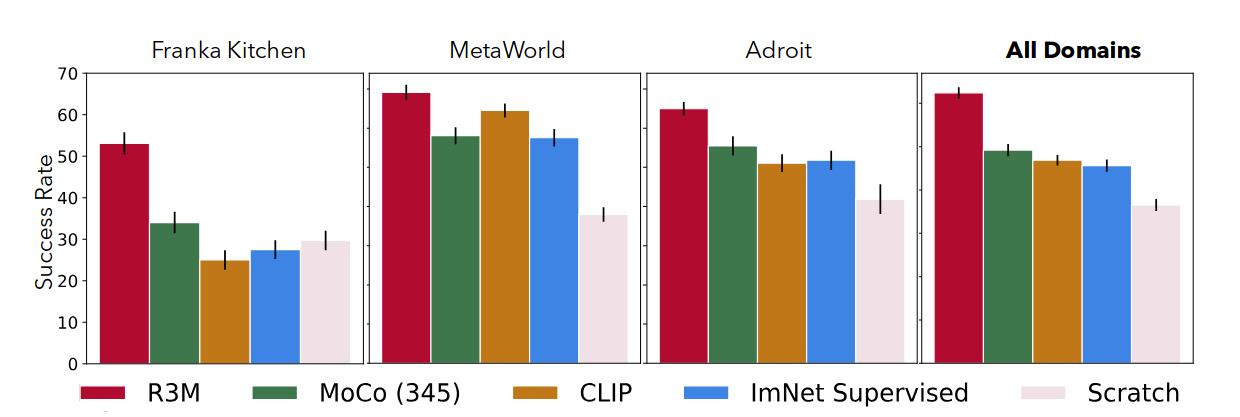

Across manipulation benchmarks such as MetaWorld, Franka Kitchen, and Adroit, R3M substantially improves data efficiency relative to training from scratch and outperforms prior visual backbones such as CLIP and ImageNet-pretrained models. These gains hold despite R3M never observing robot data during pre-training.

Fig. 5. Data-efficient imitation learning. Success rates on 12 unseen manipulation tasks show that R3M consistently outperforms MoCo (PVR), CLIP, supervised ImageNet features, and training from scratch, with standard error bars reported. [2]

In real-world experiments on a Franka Panda robot, R3M enables complex tasks such as towel folding and object placement in clutter with significantly fewer demonstrations. The results show that large-scale human video can serve as a strong perceptual prior for robotics.

However, the representation remains static. It encodes the current scene but does not explicitly model future evolution or action-conditioned dynamics. This limitation motivates subsequent work on predictive visual representations, such as Track2Act, which explicitly reason about how scenes change over time to support generalizable robot manipulation.

Context Expansion

The progression from VideoMimic to R3M reflects a shift from direct imitation toward reusable visual representations. However, both approaches primarily reason about the present: VideoMimic reconstructs a demonstrated trajectory, and R3M encodes the current scene into a static embedding. Neither explicitly models how a scene will evolve under interaction. Track2Act addresses this limitation by introducing predictive, object-centric representations that enable generalizable robot manipulation.

Rather than predicting actions or generating RGB video, Track2Act learns to predict future point trajectories that describe how objects move when manipulated. This abstraction captures the geometric and temporal structure necessary for manipulation while avoiding the brittleness of full video synthesis. As a result, Track2Act occupies an intermediate position between static visual embeddings and full world models: it anticipates future states without modeling pixels directly.

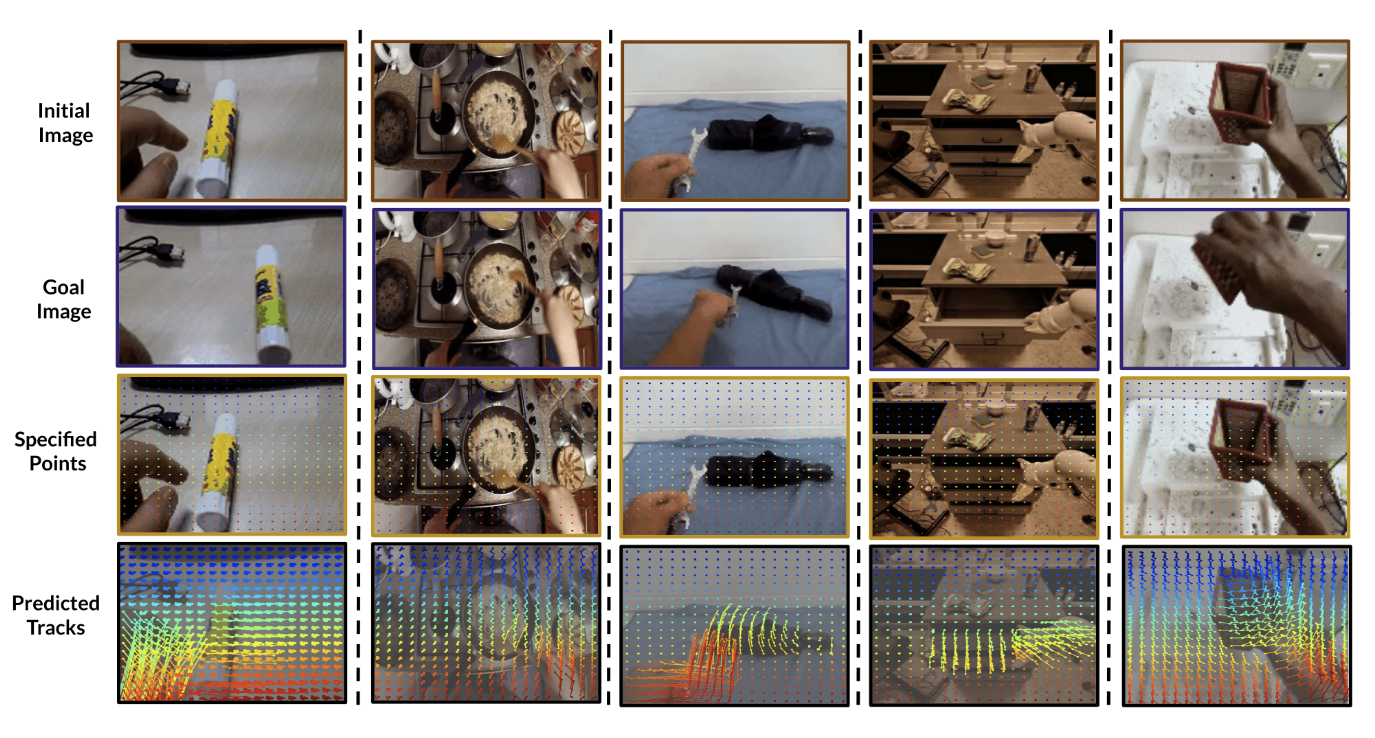

Predicting Object Motion via Point Tracks

Track2Act takes as input an initial image \(I_0\), a goal image \(I_G\), and a set of two-dimensional points specified on the object in the initial frame. Given \(p\) points and a prediction horizon \(H\), the model outputs a trajectory for each point, producing a set of object motion tracks:

\[\tau_{\text{obj}} = \left\{ (x_t^i, y_t^i) \;\middle|\; i = 1,\ldots,p,\; t = 1,\ldots,H \right\}\]These tracks form a correspondence-preserving representation of how the object should move to satisfy the goal. Because supervision is obtained from passive web videos using off-the-shelf tracking algorithms, the model scales naturally with diverse, uncurated data. By predicting motion instead of appearance, the representation abstracts away texture and lighting while retaining physically meaningful dynamics.

Fig. 6. Predicted point trajectories between an initial and goal image. [3]

From 2D Tracks to 3D Rigid Motion

To convert predicted tracks into an executable manipulation plan, Track2Act lifts the two-dimensional motion into three dimensions. Given a set of 3D object points from the first frame \(P_0^{3D}\) and camera intrinsics \(K\), the method solves for a sequence of rigid transforms \(\{T_t\}_{t=1}^H\) such that:

\[K \, T_t \, P_0^{3D} \;\approx\; \{(x_t^i, y_t^i)\}_{i=1}^p\]This optimization can be solved using standard Perspective-n-Point solvers and is well-constrained because a single rigid transform must explain the motion of multiple points. The resulting transforms describe how the object should move in the scene, independent of any specific robot embodiment.

Open-Loop Execution

After bringing the robot end-effector into contact with the object and executing a grasp, the predicted rigid transforms are converted into an open-loop end-effector trajectory. The nominal action at time step \(t\) is defined as:

\[\bar{a}_t = T_t \, e_1\]where \(e_1\) denotes the end-effector pose at the moment of grasp. This produces a complete manipulation trajectory without requiring any robot-specific training data. However, open-loop execution is sensitive to prediction errors, imperfect grasps, and unmodeled contact dynamics.

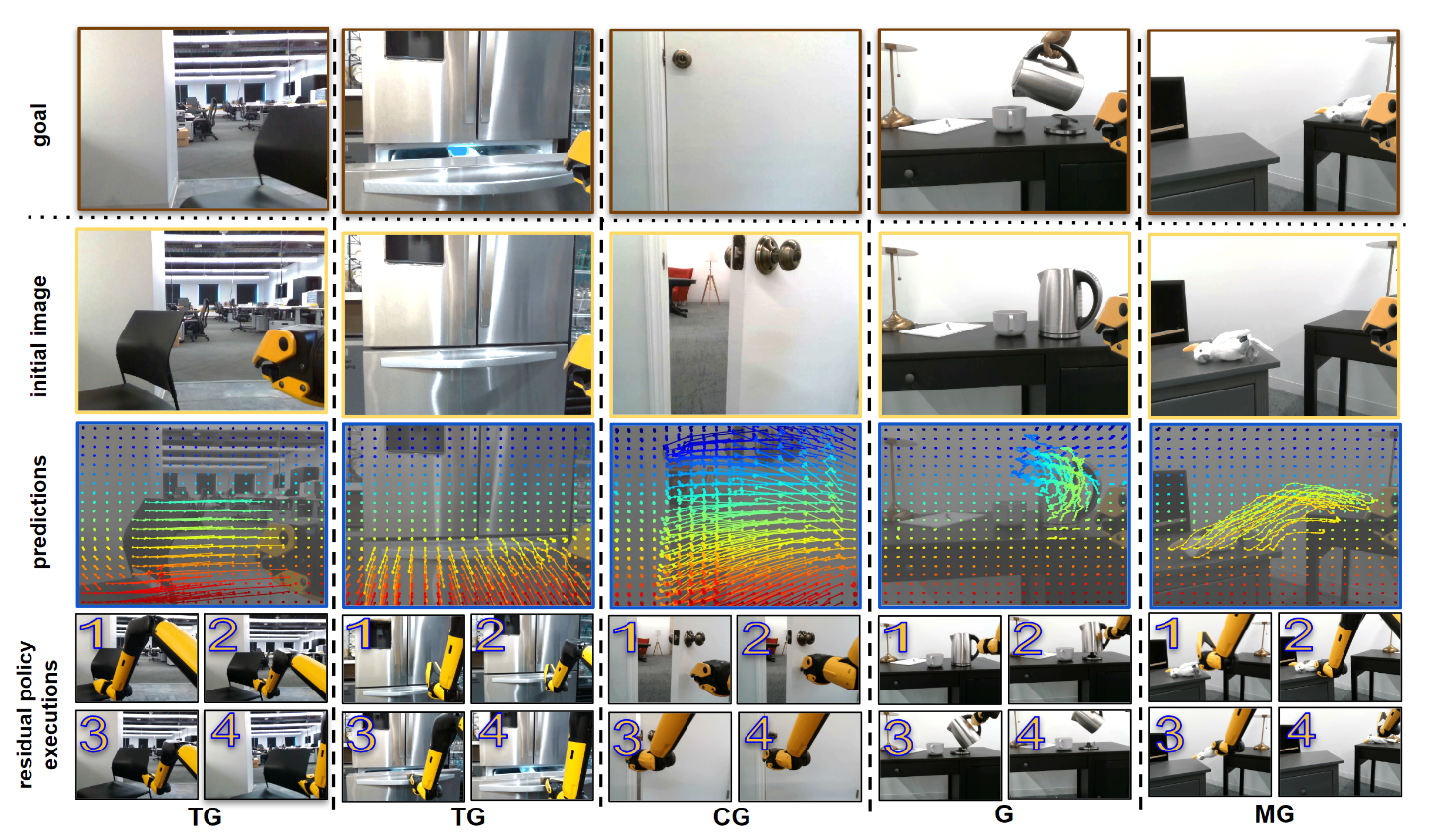

Residual Policies for Closed-Loop Correction

To improve robustness, Track2Act introduces a residual policy that corrects the open-loop plan during execution. Instead of predicting full actions, the policy outputs a correction term added to the nominal action:

\[\hat{a}_t = \bar{a}_t + \Delta a_t\]where the residual action is given by:

\[\Delta a_t = \pi_{\text{res}} \left( I_t,\; G,\; \tau_{\text{obj}},\; [\bar{a}]_{1:H} \right)\]The residual policy is trained using behavior cloning on a small amount of embodiment-specific data. Because it only learns to correct deviations from a predicted plan, the policy generalizes effectively across unseen objects, scenes, and task configurations.

Fig. 7. Open-loop execution from predicted rigid transforms with closed-loop residual correction. [3]

Conclusion

Across these approaches, a clear progression emerges in how vision supports robot control. VideoMimic demonstrates that richly structured behaviors can be transferred directly from monocular human videos when reconstruction and physics-aware learning are tightly integrated. R3M shows that large-scale video can instead be used to pretrain perceptual representations that generalize broadly across tasks, improving data efficiency without entangling vision with action learning. Track2Act bridges these paradigms by introducing prediction as a first-class component, using object-centric motion forecasts to guide manipulation while remaining agnostic to embodiment.

Taken together, these methods suggest that generalization arises not from a single monolithic model, but from carefully chosen abstractions aligned with physical interaction. Future progress will likely come from unifying these abstractions into systems that reason about uncertainty, contact, and long-horizon consequences while remaining deployable on real robots.

Acknowledgements

We thank the TAs of the Computer Vision this course for providing the class with relevant materials to supplement all of our chosen topics for the final project.

Reference

[1] Arthur Allshire, Hongsuk Choi, Junyi Zhang, David McAllister, Anthony Zhang, Chung Min Kim, Trevor Darrell, Pieter Abbeel, Jitendra Malik, Angjoo Kanazawa: “Visual Imitation Enables Contextual Humanoid Control”, 2025; [https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.03729 arXiv:2505.03729].

[2] Suraj Nair, Aravind Rajeswaran, Vikash Kumar, Chelsea Finn, Abhinav Gupta: “R3M: A Universal Visual Representation for Robot Manipulation”, 2022; [https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.12601 arXiv:2203.12601].

[3] Homanga Bharadhwaj, Roozbeh Mottaghi, Abhinav Gupta, Shubham Tulsiani: “Track2Act: Predicting Point Tracks from Internet Videos enables Generalizable Robot Manipulation”, 2024; [https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.01527 arXiv:2405.01527].