Anime Sketch Colorization and Style Transfer

In this project I explore how to color a sketch in the style according to another colored image.

- Introduction

- Theory

- Dataset

- Methodology

- Results

- Discussion

- Demo and Highlight Video

- Reference

- [8] Te-Lin Wu, Shao-Hua Sun, ACGAN-PyTorch, (2017), GitHub repository, https://github.com/clvrai/ACGAN-PyTorch

Introduction

This project is based on the paper “Style Transfer for Anime Sketches with Enhanced Residual U-net and Auxiliary Classifier GAN” by Zhang et al.

Theory

U-Net

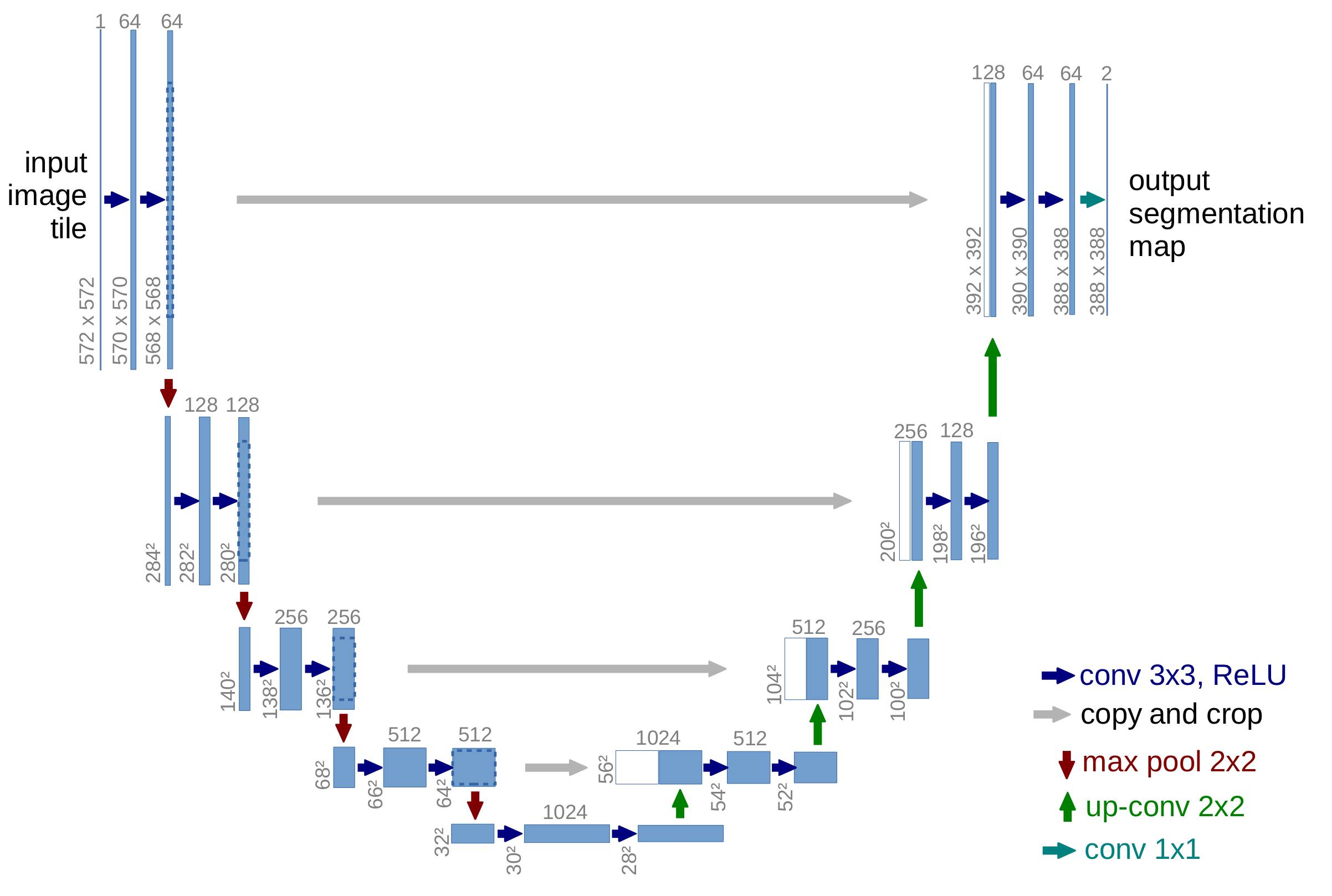

The U-Net is initially proposed by Ronneberger et al. in 2015 to be used for biomedical image segmentation [1]. In a segmentation task, a class label should be assigned to each pixel, so it is important for localization. In a typical convolutional network, the later layers have a receptive field that essentially encompasses the whole image, which goes against the idea of “localization”. As such, in addition to the normal contracting layers of convolutional neural networks, Ronneberger et al. proposed appending an expanding branch to the normal contracting layers of convolutional networks. Furthermore, there are “skip connected layers”, where feature maps from earlier layers skip over layers and gets concatenated to the expanding branch, which should “reintroduce” the local features to those layers. This architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: This is the model architecture as proposed in the original U-Net paper. [1]

AC-GAN

AC-GANs is a variant of the GAN architecture in which every image is generated using a particular class label in addition to the noise vector. The discriminator then gives both a probability distribution over whether the image is generated or not (the source) and a probablility distribution over the class labels [7]. The loss function, as such, also changes. It is composed of two parts, the log-likelihood of the correct source \(L_S\), and the log-likelihood of the correct class, \(L_C\).

\[L_S=\mathbb{E}[\log P(S=real \mid X_{real})]+\mathbb{E}[\log P(S=fake\mid X_{fake})]\] \[L_S=\mathbb{E}[\log P(C=c \mid X_{real})]+\mathbb{E}[\log P(C=c\mid X_{fake})]\]The discriminator is trained to maximize \(L_S+L_C\) as the discriminator wants to maximize being able to guess the correct source and the correct class label. On the other hand, the generator is trained to maximize \(L_C-L_S\), which would entail maximizing \(L_C\) and minimizing \(L_S\). This makes intuitive sense, as we want the generator to generate an image that fits the given class as close as possible while having it look like a real image.

The Sketch Colorization Model

Zhang et al. modifies the AC-GAN architecture for the sketch coloring task. The generator portion of the AC-GAN is built on top of the U-Net, as coloring can be loosely thought of as a segmentation task (i.e. attaching three numbers to each pixel). The noise vector used in AC-GANs in this case is the sketch, while the class label is the “style vector”, the flattened output to VGG’s convolutional layers.

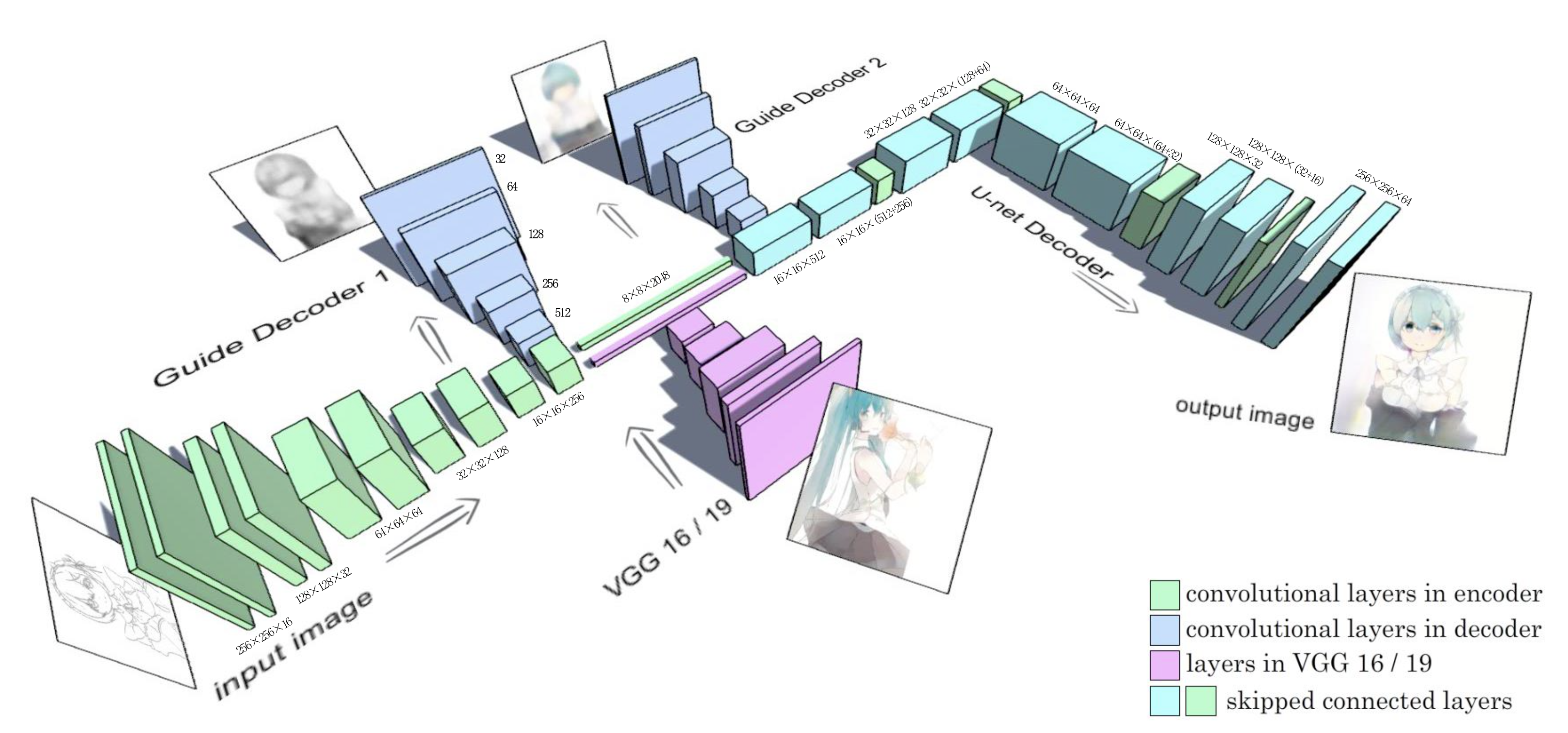

The exact generator model architecture is illustrated in Figure 2. The immediate noticeable features in this architecture is the addition of the style vectors later in the generator (rather than in the beginning with the sketch). The reasoning is that at the end of the contracting branch of the U-Net, we would have a vector that is a high-level, global representation of the sketch. By adding the VGG style vector, we would be adding color into this representation, and so when we go through the expanding branch, we would reconstruct the original sketch with the colors added.

Figure 2: The sketch colorization model architecture proposed in Zhang et al’s paper. [2]

Another addition to the U-Net that Zhang et al. made is the addition of guide decoders. These are added to prevent the vanishing gradient problem. They are added at the entry and exit of mid-level layers. The decoder at the entry of the mid-level layer produce a monochrome image, as colors have not yet been introduced, and the one at the exit creates the colored image, after color addition.

Since the overall architecture is a AC-GAN, we use the loss proposed in the original AC-GAN mentioned before. However, this is not sufficient for our task, as we want the output image to look as close as the “correctly colored image” (addressed later) as possible. As such, we further add another \(\lambda L_G\), where \(\lambda\) is a scalar hyperparameter. \(L_G\) is given as follows:

\[L_{G}=\mathbb{E}_{x,y\sim P_{data}(x,y)}[\lVert y-G_f(x,V(x) \rVert_1+\alpha\lVert y-G_{g_1}(x)\rVert_1+\beta\lVert T(y)-G_{g_2}(x,V(x))\rVert_1]\]where \(x\) is the input sketch, \(V(x)\) is the output of the VGG 19 layer (refer to the Architecture section below), \(G_f(x,V(x))\) is the model’s output colorized image, \(G_{g_1}(x)\) and \(G_{g_2}(x)\) are the outputs of the two guide decoders, \(y\) is the label colorized image, \(T(y)\) is the grayscaled label colorized image. \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) are magic constants that are 0.3 and 0.9, respectively. These numbers are tested to be optimal empirically by Zhang et al. [1]. Note that the contribution to the loss function by the first guide decoder is the difference between its output and the grayscaled colorized image. This is because the first guide decoder, as noted before, would generate a monochrome image.

Dataset

The original Zhang et al. paper did not mention the exact dataset they trained the dataset by. However, this project is continued to be explored by Zhang and his group of researchers [3]. In the paper that outlined the third-generation of this model, they mentioned training using data scraped from the Danbooru database [4]. The Danbooru database is a large-scale anime image database with user-annotated tags [6]. Although the third generation of the model has a significantly different architecture (it utilizes two U-Nets instead of just one), due to the similarity of the task, the same training data would be used for this project. As such, for this project, we scraped all images that satisfies the following criteria: (1) it is part of the Danbooru 2021 512 by 512 pixels dataset, (2) it has a “s”, meaning Safe-For-Work, rating, and (3) it has the tag white_background. The white_background tag typical portraits, those with a character on a white background. The need for a blank background is because the model is not designed to color arbitrary anime characters in any settings. Zhang et al. posited that there are other model architectures that are more suitable to colorize manga or images with background [3]. After all of these images are scraped, they have to be vetted first, as the Danbooru dataset pad the images with black borders when the image is not a perfect square. All images that have either height of width go below 256 by 256 after the border removal are left out of the final dataset. All images that have both height and width greater than 256 are then resized to 256 by 256.

Using this method and help from a script written by user Atom-101 on Github, a total of 31187 images are scraped [6]. We then carry out border removal and resizing on the 31187 images, after which 30837 images remained. These images are colored images, and so they serve as our “colorized” images (the labels). The database doesn’t actually have the sketch version of these images, so these have to be extracted from these colorized images. The sketch images (part of the input) are extracted from the original image by applying a grayscale, an inversion, and a Gaussian blur. Zhang et al. specified that their dataset is extracted using a neural network trained by Zhang et al. [4]. However, due to the slow speed of the model (it takes two second to process an image), this option was abandoned.

We have now obtained the sketches (i.e. the noise vector) that we will use to train the generator, but we still need the style images (i.e. class label) and the label image to get our loss function. We note that there is not an easy way to obtain these style images, as the Danbooru dataset does not have multiple colorized version of a sketch, each with a different style. Furthermore, there is no objectively “right answer” to what a “sketch that is colorized according to a particular style” is. As such, we notice that the colorized images that we used to exact the sketchs from are by definition sketches colored to the style of itself. As such, we use the original, colorized images as both the style image and the label image.

Methodology

Implementation of Original Model

The model architecture is implemented as closely as possible to the original paper. However, due to the paper not having the clearest illustration and verbal descriptions, some parts have to be inferred and this might have caused some discrepancy between this project’s implementation and the original implementation. These inferences (including placement of ReLU layers, pooling methods, padding methods, and depths of skipped connected layers) are educated guesses based on the architecture of the original U-Net [1,2]. Efforts are made to salvage the original model by scouring the GitHub repositories by Zhang, but the original source code used to train the model had never been published, and the pre-trained model also seemed to be lost since 2018 [3]. The PyTorch implementation is as outlined below:

class Generator(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super(Generator, self).__init__()

self.downsample_128 = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(3, 16, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 16 * 256 * 256

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(16, 16, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 16 * 256 * 256

nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2), #16 * 128 * 128

nn.Conv2d(16, 32, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 32 * 128 * 128

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(32, 32, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect') # 32 * 128 * 128

)

self.downsample_64 = nn.Sequential(

nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2), #32 * 64 * 64

nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 64 * 64 * 64

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 64 * 64 * 64

)

self.downsample_32 = nn.Sequential(

nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2), #64 * 32 * 32

nn.Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 128 * 32 * 32

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(128, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 128 * 32 * 32

)

self.downsample_16 = nn.Sequential(

nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2), # 128 * 16 * 16

nn.Conv2d(128, 256, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 256 * 16 * 16

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(256, 256, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 256 * 16 * 16

)

self.bottom_8 = nn.Sequential(

nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2), # 256 * 8 * 8

nn.Conv2d(256, 2048, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 2048 * 8 * 8

)

self.vgg = VGG_19_fc_1_output()

self.vgg_2048 = nn.Linear(4096, 2048)

self.upsample_16_1 = nn.ConvTranspose2d(2048, 512, kernel_size=2, stride=2) # 512 * 16 * 16

self.upsample_16_2 = nn.Sequential(

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 512 * 16 * 16

)

self.upsample_32 = nn.Sequential(

nn.ConvTranspose2d(512 + 256, 128, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 128 * 32 * 32

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(128, 128, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 128 * 32 * 32

)

self.upsample_64 = nn.Sequential(

nn.ConvTranspose2d(128 + 128, 64, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 64 * 64 * 64

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 64 * 64 * 64

)

self.upsample_128 = nn.Sequential(

nn.ConvTranspose2d(64 + 64, 32, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 32 * 128 * 128

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(32, 32, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 32 * 128 * 128

)

self.upsample_256 = nn.Sequential(

nn.ConvTranspose2d(32 + 32, 64, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 64 * 256 * 256

nn.ReLU(inplace=True),

nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 64 * 256 * 256

nn.Conv2d(64, 3, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1) # 3 * 256 * 256

)

# Guide decoders

self.guide_dec_1 = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(256, 512, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 512 * 16 * 16

nn.ConvTranspose2d(512, 256, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 256 * 32 * 32

nn.ConvTranspose2d(256, 128, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 128 * 64 * 64

nn.ConvTranspose2d(128, 64, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 64 * 128 * 128

nn.ConvTranspose2d(64, 32, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 32 * 256 * 256

nn.Conv2d(32, 3, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1) # 3 * 256 * 256

)

self.guide_dec_2 = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(512, 512, kernel_size=3, padding=1, stride=1, padding_mode='reflect'), # 512 * 16 * 16

nn.ConvTranspose2d(512, 256, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 256 * 32 * 32

nn.ConvTranspose2d(256, 128, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 128 * 64 * 64

nn.ConvTranspose2d(128, 64, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 64 * 128 * 128

nn.ConvTranspose2d(64, 32, kernel_size=2, stride=2), # 32 * 256 * 256

nn.Conv2d(32, 3, kernel_size=1, padding=0, stride=1) # 3 * 256 * 256

)

def forward(self,x):

sketch, style = x

skip_128 = self.downsample_128(sketch)

skip_64 = self.downsample_64(skip_128)

skip_32 = self.downsample_32(skip_64)

skip_16 = self.downsample_16(skip_32)

self.vgg.eval()

with torch.no_grad():

vgg_4096 = self.vgg(style)

vgg_hint = self.vgg_2048(vgg_4096).unsqueeze(2).unsqueeze(3)

bottom_8 = self.bottom_8(skip_16)

bottom_sum = vgg_hint + bottom_8

up_16_1 = self.upsample_16_1(bottom_sum)

up_16 = self.upsample_16_2(up_16_1)

up_32 = self.upsample_32(torch.cat([up_16, skip_16], dim=1))

up_64 = self.upsample_64(torch.cat([up_32, skip_32], dim=1))

up_128 = self.upsample_128(torch.cat([up_64, skip_64], dim=1))

# turn decoder 1 result into grayscale

grayscale_dec_1 = torch.mean(self.guide_dec_1(skip_16), dim=1).unsqueeze(dim=1)

return grayscale_dec_1, self.guide_dec_2(up_16_1), self.upsample_256(torch.cat([up_128, skip_128], dim=1))

Note that the forward() function returns the output of the guide decoders and the actual output image. This is for convenience of calculating the loss function. The VGG_19_fc_1_output() is the pre-trained VGG-19 model, except given an image, it produces a vector of size 4096 (the input to the first fully connected layer). This is in accordance to the design outlined by Zhang et al. in their paper [2].

Before the images are fed into the model, the pixels are normalized to values between 0 and 1 as per standard practice.

Innovations made to previous model

In addition to the above models, we explored making several modifications to the model, including:

- Remove the guide decoders entirely and replace them with batch norm between each convolutional layers instead

- Normalizing the sketch and/or style image using ImageNet means and standard devations before they are given to the model

- Utilizing a style vector from Inception v3.

The reasoning behind modification 1 is that although not theoretically understood, batch norm empirically seems to be capable of stabilizing the training of the network and help propagate the gradient. As such, since the guide decoders are there to help mitigate the vanishing gradient problem, we replace them with batch norm layers in an attempt to make the model slightly simpler.

VGG, a network trained on ImageNet, is trained by normalizing the input to mean = [0.485, 0.456, 0.406] and std = [0.229, 0.224, 0.225]. The original Zhang paper did not specifically mention whether their style image was normalized before extracting the style vector, so a comparison between normalizing and not normalizing the style was made. Furthermore, in the original paper it seems like the sketch image was not normalized at all, which might be problematic, as the style vector were extracted from a normalized image then added to an unnormalized image. As such, we explore the method of normalizing the sketch, adding normalized style vector, reconstructing the image in the normalized image, then “undoing” this color normalization.

In Zhang’s paper, the global style vector of length 4096 is first passed through a trainable 2048 linear layer before being added to the \(8\times 8\times 2048\) stage of the U-Net via NumPy broadcasting. It seems that the flattened 4096 style vectors lack spatial information to begin with, and the fact that it is broadcasted may further exacerbate this issue, which we hypothesize would impact the resulting image. As such, we try to use the last layer from Inception V3, as it coincidentally has the same spatial \(8\times 8\times 2048\) shape, which would simultaneously eliminate the need to flatten and broadcast, the very two steps that might result in losing spatial information. Note that when extracting the Inception style vectors, the style images have to first be padded to the minimal required size of \(299 \times 299\) using reflection.

Training

All the models are trained using the Adam optimizer using default PyTorch parameters (lr=0.001, betas=(0.9, 0.999), eps=1e-08). 80% of the total 30837 images is used as the training set, 10% as the validation set, and 10% as the test set. Models are trained for at least 10 epochs each, with a batch size of 32. For each epoch, there are 6 checkpoints, and the images are evaluated over the validation dataset using MSE from the output image to the label image. The training process is heavily derived from the AC-GAN implementation of Joseph Lim’s group at USC [8].

Results

The model is trained with the Adam optimizer using default PyTorch parameters (lr=0.001, betas=(0.9, 0.999), eps=1e-08). The “best” models (i.e. those that achieved the best performance on the validation set at checkpoints throughout the training process) are saved, and we show the output of the best models from three model architectures. One is the original model proposed by Zhang with the guide decoders (model 1), another one uses batch norm and normalized style vector (model 2), while the last one uses batch norm, normalized style and sketch vector, and Inception_v3 style vectors (model 3).

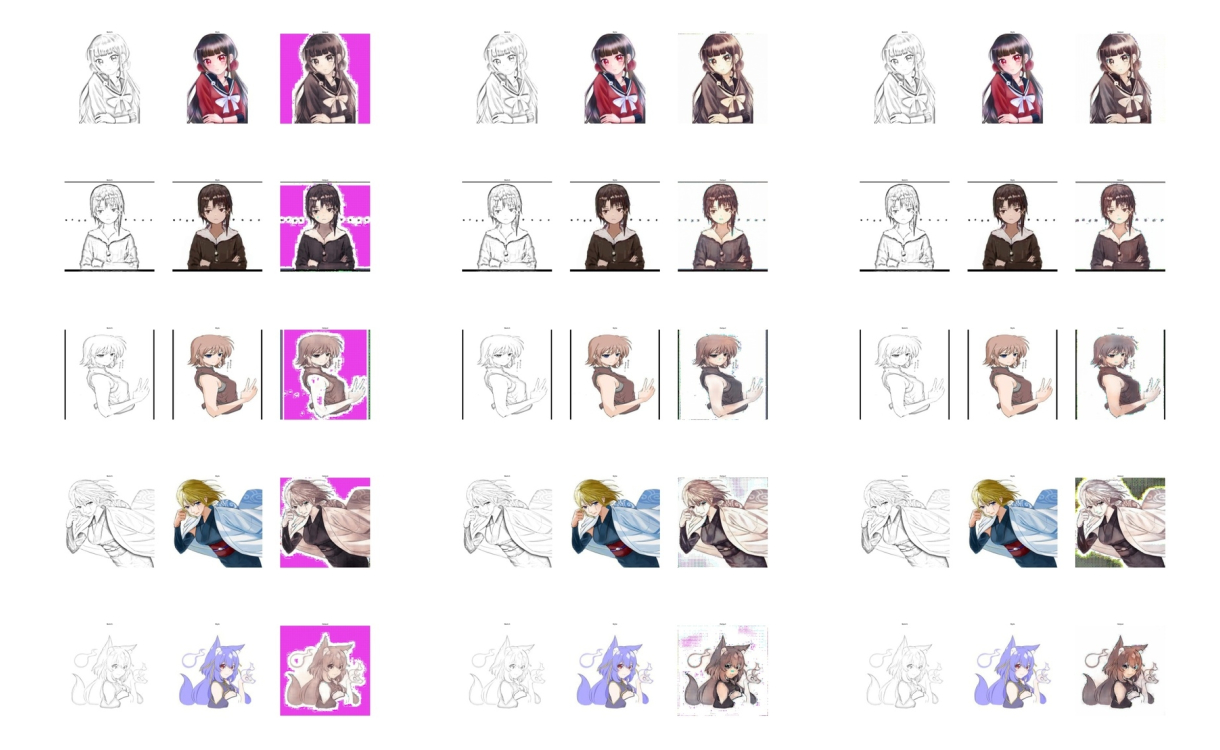

Figure 3: The output image of the different model architectures over the same five images from the test dataset. The columns from left to right are images produced by models 1, 2, and 3, respectively. In each column, there are three sub-columns, which again from left to right are the sketch image, style image, and output image. Ideally, the style and output image should be identical. [1]

Discussion

It is quite obvious that all three models failed in the very basic task of coloring the sketch with its original images. Model 1, with the unnormalized style vector, seems to color all the background with pink, and this pink seems to stay constant across all output images. Furthermore, although the specific color scheme are not applied to any of the output image, a sensible shading is applied to different parts of the image, such as a lighter shading to the face and a darker shading to the clothing. However, the similar color scheme used in all the images suggests that the model simply averaged the color in different parts of the image and applied them to all images. The pink background suggests that without normalizing the image before inputting it into the VGG network, the style vector’s information would be reduced.

The most noticeable difference between model 2 and model 1 is that model 2 is able of coloring the background white, like the input image. This reinforces the importance of normalizing the style image before extracting the style vector. However, aside from being capable of correctly removing the color from the background, there is not a noticeable difference in the character in the sketches. That is, the characters are still colored with the same average color scheme across the dataset. However, the similar property of the shading quality suggests that batch norm layers are indeed capable of handling the vanishing gradient problem that the guide decoders are designed to handle.

The difference between model 2 and model 3 is almost nonexistent. As illustrated in the top three rows, for most of the image, the colorization quality are essentially identical. Both model correctly identifies the white background while applying a sensible shading with no colors. Row 4 is an example of model 2 outperforming model 3, as seen by the noisy background in model 3’s output. However, row 5 is an example of model 3 outperforming model 2, where it is model’s 2 output that has a slightly noisy background. As such, in terms of the colorization capability, the two models are relatively similar. This seems to suggest that the concern of the flattened broadcasted style vector reducing spatial information is not that important. However, one noticeable improvement that is not shown in the output image is the speed and compactness of Inception. Model 3 can process each batch in 40% less time than model 2 during training. Furthermore, model 3 takes less than 30% of the storage that model 2 takes up.

Future work on this topic is being pursued by Lvmin Zhang and his group [4]. However, we are still unable to recreate the results promised by his paper from 2017, where rich colorization and effective style transferring is possible. There are still many parameters that are still unexplored during training such as increasing the magnitude of \(\lambda\) in the loss function (i.e. punishing the model more when the pixels are different). Learning rate decay can also be explored to see if it can lower the loss even more. Furthermore, one can also explore using better style extractors. Both VGG and Inception are networks that are trained using ImageNet for classification, so the features extracted by these networks would intuitively be more focused on the semantics rather than the color scheme. As such, one can consider finetuning the pretrained VGG and Inception v3 (rather than freezing them like rigth now) to get a more colorful representation of the input images.

Demo and Highlight Video

The link to the project is here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1Cx3XkDEC53U4vfb4ZdJp8-FBDsENqoBb?usp=sharing. You can find the demo Colab notebook titled “Demo” there.

The highlight video can also be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1FOws3vS4QxQe_gpuK07pDYWxG5k4nb4y/view?usp=sharing.

Reference

[1] Lvmin Zhang, Yi Ji, Xin Lin. 2017. Style Transfer for Anime Sketches with Enhanced Residual U-net and Auxiliary Classifier GAN. arXiv:1706.03319

[2] Olaf Ronneberger, Philipp Fischer, Thomas Brox. 2015. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. arXiv:1505.04597

[3] The Style2PaintsResearch Team, Style2Paints, (2018), GitHub repository, https://github.com/lllyasviel/style2paints

[4] Lvmin Zhang, Chengze Li, Tien-Tsin Wong, Yi Ji, and Chunping Liu. 2018. Two-stage sketch colorization. ACM Trans. Graph. 37, 6, Article 261 (December 2018), 14 pages. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3272127.3275090

[5] Atom-101, Danbooru Dataset Maker, (2020), GitHub repository, https://github.com/Atom-101/Danbooru-Dataset-Maker

[6] Anonymous, The Danbooru Community, & Gwern Branwen; “Danbooru2021: A Large-Scale Crowdsourced and Tagged Anime Illustration Dataset”, 2022-01-21. Web. Accessed February 20, 2022 https://www.gwern.net/Danbooru2021

[7] Augustus Odena, Christopher Olah, Jonathon Shlens. 2017. Conditional Image Synthesis with Auxiliary Classifier GANs. arXiv:1610.09585