Video Grounding

Topic: Video Grounding

- Video Presentation

- Github Code Link

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Video grounding models

- Experiments on 2D TAN

- Baseline Results:

- Transfer learning for Animal Kingdom:

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- References

Video Presentation

Github Code Link

Abstract

In this project, we analyze one prominent video grounding model to explore in depth: 2D-TAN [1]. We analyze the performance of this model on ActivityNet [5], Charades-STA [6], and TACoS [7] datasets based on provided pre-trained checkpoints. In addition, we introduced a novel dataset, Animal Kingdom [8], to analyze the extensibility of the 2D-TAN model to a new video domain by evaluating the results of the pre-trained models on this novel dataset. To further improve the results, we used transfer learning on the best-performing model, then evaluated and analyzed the final results. The results showed low extensibility from the untuned pre-trained models, but with transfer learning, the fine-tuned model performed quite well on the novel dataset. We conclude that though the baseline pre-trained 2D-TAN models fail to generalize across domains, small amounts of transfer-learning and fine-tuning can quickly scale 2D-TAN across novel applications.

Introduction

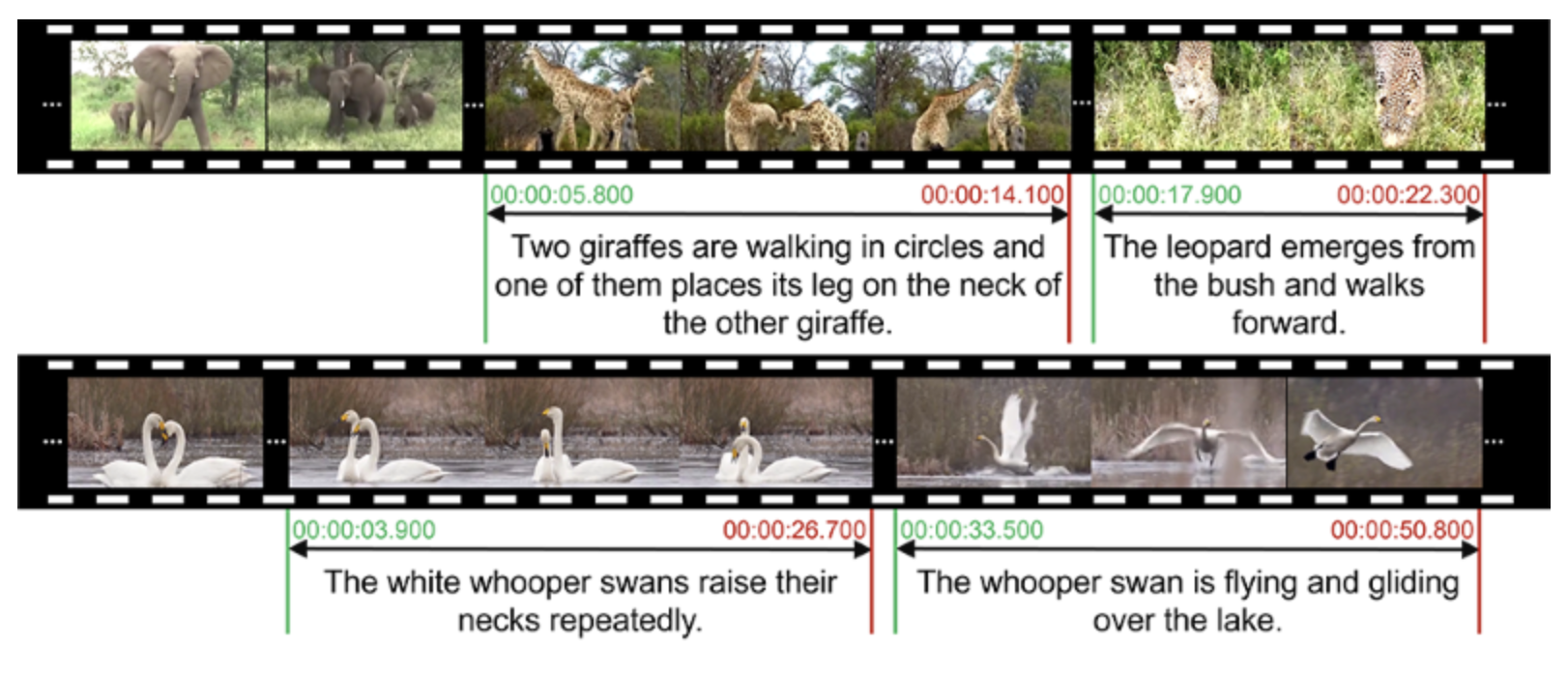

Video grounding is the task of grounding natural language descriptions to the visual and temporal features of a video. The requirement to tie together and reason through the connections between these 3 domains makes this task highly complex. However, it proves very useful in applications such as video search, video captioning, and video summarization.

Our project goal was to first replicate and explain the results of the 2D-TAN model across the given pre-evaluated datasets(ActivityNet, Charades-STA, and TaCOS). But because all of these datasets were human-focused, we wanted to also analyze the results of these 2D-TAN video grounding models on another domain, the animal kingdom. In fact, we wanted to leverage a novel dataset, Animal Kingdom, on this video grounding model to see how 2D-TAN could generalize to a new, unseen domain, namely annotations and videos of animals doing activities. Video grounding for animal actions is an important task for zoologists, biologists, behavioral ecologists, or even pet owners that seek to identify animal-based events in video.

Our initial hypothesis for the data was that the pre-trained models out of the box would perform worse on the Animal Kingdom dataset due to a couple factors. The first is that word embeddings may have difficulty encoding some of the very specific animal classes in our Animal Kingdom data, which would lead to more difficulty identifying groundings for the novel data. Secondly, as the models were pre-trained on human activities, it would perform worse on these animal activities that it had never seen before. Our second hypothesis was that we could generalize the 2D-TAN model through transfer learning and fine-tune the 2D-TAN model for this downstream task, allowing for substantial performance increases for the downstream task.

Video grounding models

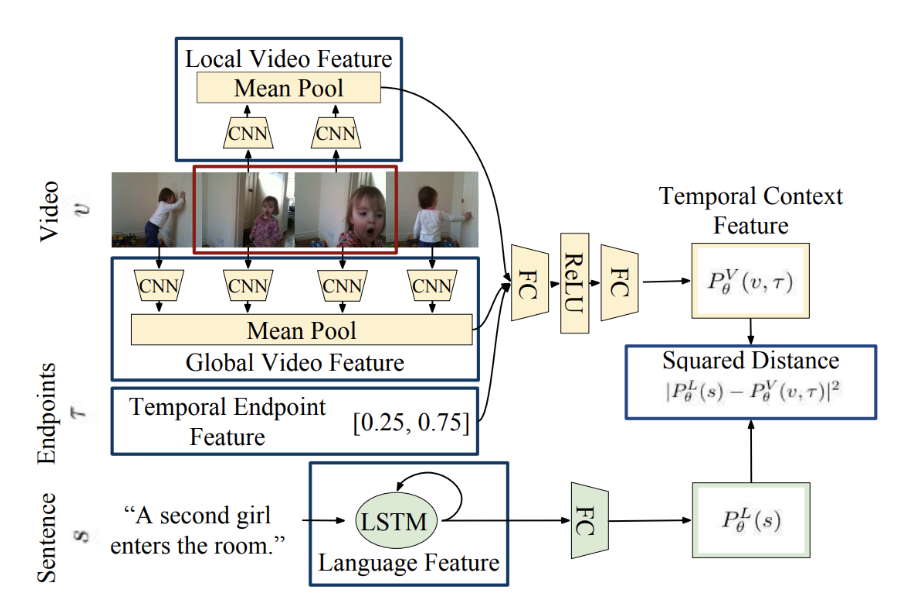

Moment Context Network

The Moment Context Network (MCN) [2], proposed by Hendricks in 2017 is one of the earliest models for the video grounding task.

First, sampled frames of the video are passed through a vgg model to extract rgb features. It can also be passed through [4] to extract optical flow features. This paper demonstrates a fusion method where both the rgb features and optical flow features are used for an increase in performance, however they can also be used separately. These features are expected to help identify attributes and objects.

Adding Global Context

One of the central challenges of video grounding comes from temporal context within videos. For example, the query: “the girl jumps after falling” is different from “the girl jumps for the first time”. However, the ground truth clips may look similar, both including the girl jumping.

In MCN, the local features of a clip are represented with the output of a mean pool applied across the features extracted from frames within a clip. To incorporate global context, the local video feature is passed in with a global video feature which is extracted by applying mean pool to all frames of the entire video. In addition, a temporal encoding, which represents the relative time position of a clip normalized between 0 and 1, is passed in.

Making Predictions

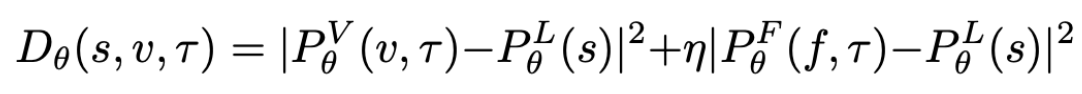

The final prediction output of a clip is created with a sum of squares.

Here, $s$ is sentence query, $v$ is the input video frames, and tau represents the temporal position. $P^V$ represents the temporal context output for the rgb features, $P^F$ represents the temporal context output for optical flow features, and $P^L$ represents the output from the language model.

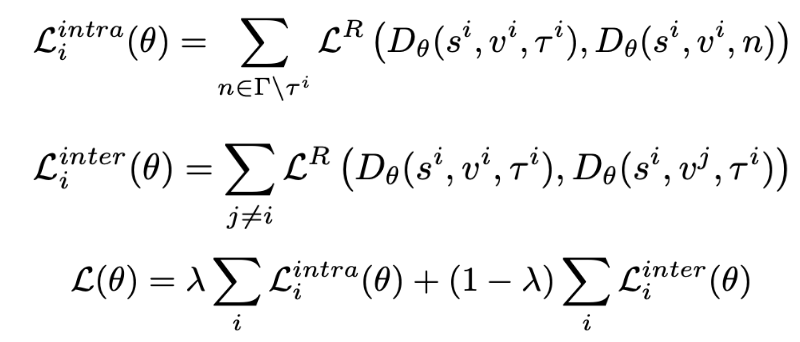

Calculating Loss

The loss between the model proposal and the ground truth is found by considering the loss across two different domains: inter-video (across all different videos) and intra-video (within the same video).

This is necessary because comparing moments only within the same video will lead to the learning of distinctions between subtle differences. However, it is important that the model also learns the semantic difference between broad concepts like “girl” vs. “sofa.”

Limitations of MCN

The MCN introduced the important idea of evaluating intra-video temporal meaning. However, the MCN lacks flexibility. The paper mentions that each video is split into 5 second clips, with ground truth labels of their custom dataset also being made on these 5 second intervals. This means that only certain custom datasets can be used to train this model. More critically, temporal proposals will be inaccurate. We do not get flexibility to make 1 second proposals or 1 minute proposals.

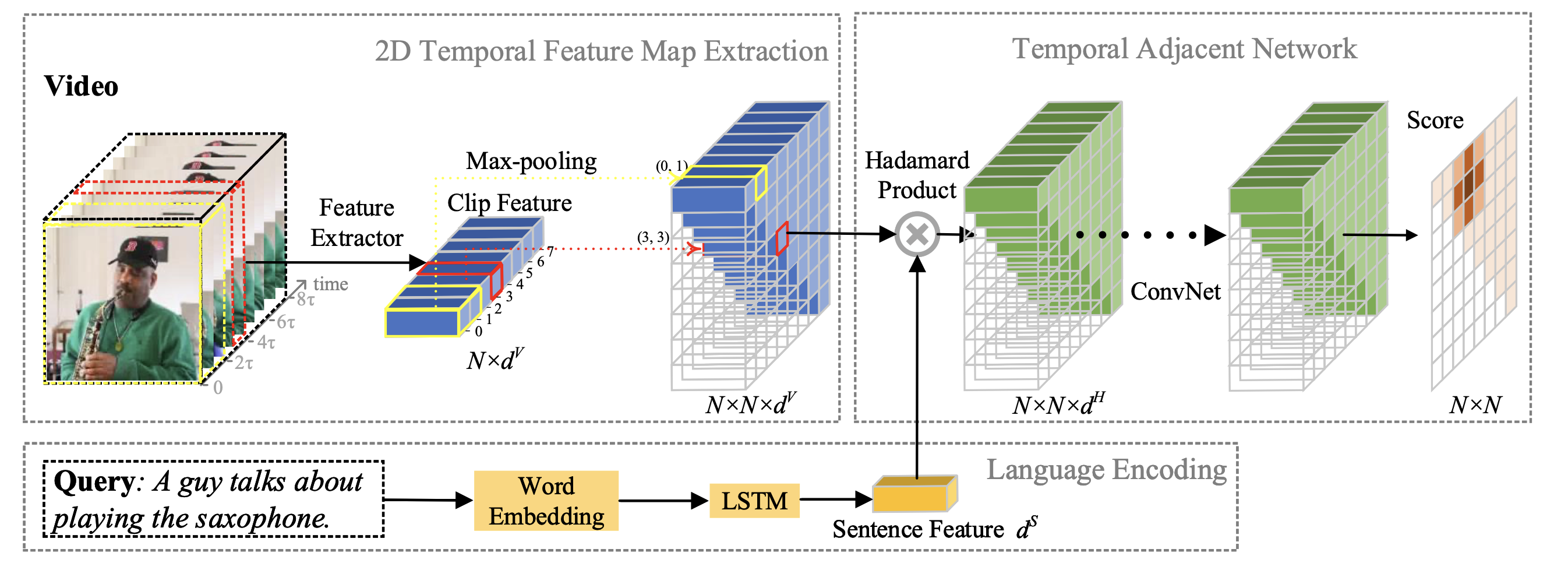

2D Temporal Adjacent Network

The 2D Temporal Adjacent Network (2D TAN) [1] introduces a novel method to address the lack of flexibility in MCN. This is done by creating a 2d feature map with one dimension representing start time, and another dimension representing stop time. The highest score here will predict a clip of variable length.

Structure

The video feature extractor here is largely the same as in MCN. The differences are: 1. This paper does not use the fusion method, however it could be applied. 2. Clips in MCN are extracted through mean pooling. This paper uses either max pooling or a more complex stacked convolution method [3] (this will be discussed further later).

Differences in this model come from the different selection of features extracted. While pooling was applied over fixed clip proposals used in the MCN, 2D TAN extracts features and performs pooling to fill the 2D Temporal Feature Map. This includes both short and long moments. As mentioned earlier, position (a,b) on the map represents the moment from time a to time b. This is what gives 2D TAN its flexibility for clip length, which improves accuracy.

Similar to MCN, the language encoding in 2D-TAN is also done by an out-of-the-box method.

Code for creating map (which is the critical/novel part here):

dense.py:

class PropMaxPool(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, cfg):

super(PropMaxPool, self).__init__()

num_layers = cfg.NUM_LAYERS

self.layers = nn.ModuleList(

[nn.Identity()]

+[nn.MaxPool1d(2, stride=1) for _ in range(num_layers-1)]

)

self.num_layers = num_layers

def forward(self, x):

batch_size, hidden_size, num_clips = x.shape

map_h = x.new_zeros(batch_size, hidden_size, num_clips, num_clips).cuda()

map_mask = x.new_zeros(batch_size, 1, num_clips, num_clips).cuda()

for dig_idx, pool in enumerate(self.layers):

x = pool(x)

start_idxs = [s_idx for s_idx in range(0, num_clips - dig_idx, 1)]

end_idxs = [s_idx + dig_idx for s_idx in start_idxs]

map_h[:, :, start_idxs, end_idxs] = x

map_mask[:, :, start_idxs, end_idxs] += 1

return map_h, map_mask

(Note: This is simplified, because in practice we make sparse proposals for efficiency)

Making Predictions

To make predictions, a Hadamard product (or element wise product) is applied to the outputs of the sentence feature and 2D temporal map features. This creates a 2d map of weights where the most likely video segment is highlighted with the highest weight.

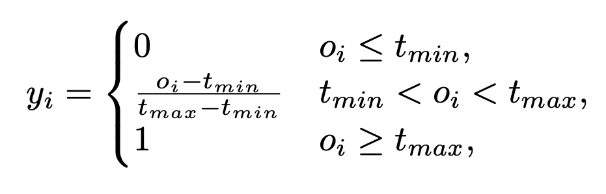

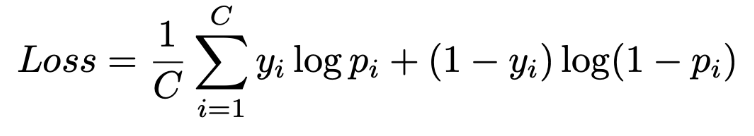

Calculating Loss

Loss is calculated using a scaled IoU over the time proposal. The IoU scaling can help keep scores more uniform across the different lengths of ground truth labels. Then, cross entropy loss is applied to minimize the loss.

$o_i$ is the IoU value. $t_{min}$ and $t_{max}$ are thresholds used to scale.

Experiments on 2D TAN

The flexibility of the 2D TAN model made it promising for a wide range of video grounding applications. Because of this, we decided to reconstruct the model, first replicating the results in order to ensure correct model performance. We first analyzed the model on the three sets of data used in the paper: Charades-STA, ActivityNet Captions, and TACoS. Then, we introduced the model to a new dataset, AnimalKingdom to study the extensibility of 2D-TAN.

Creating features using VGG and C3D:

To pass the AnimalKingdom dataset into the Charades-STA and TACoS pretrained models, we must extract the features of each video using a pretrained VGG model and pretrained C3D model, respectively. To do this, we wrote the following code to extract features.

VGG

For our VGG features, we sampled every 8 frames of each video. We use this sparse sampling technique and tuned this number so that we could get a good representation of a video, while increasing efficiency.

To prevent distortion for each input frame, we utilized a method that first resized the shorter height dimension to 224, then took a center cropped region of 224x224.

def main():

"""

Main function.

"""

# get pretrained model

net = models.vgg16(pretrained=True)

net.classifier = nn.Sequential(

*list(net.classifier.children())[:-1],

)

net.cuda()

net.eval()

for video_path in os.listdir("./dataset"):

vid = visionio.read_video("./dataset/"+video_path)[0]

vid_features = torch.zeros(((len(vid)+7)//8,4096))

for i in range(0,len(vid),8):

frame = vid[i]

# resize frame to 224x224

frame = torch.permute(frame, (2, 0, 1))

# perform resize

frame = transforms.Resize(224)(frame)

# get 224x224 center region. This method prevents distortion.

frame = fn.center_crop(frame, output_size=[224])

frame = frame[None, :]

frame = frame.float()

frame = frame.cuda()

with torch.no_grad():

vid_features[i//8] = net(frame)

torch.save(vid_features,"./vgg-features/"+video_path+".pt")

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

C3D

For our C3D features, we sampled clips of 16 frames each every 8 frames. This matches the original specifications used for TACoS in the original paper, and gives a good representation of all segments of the video.

We also employed the same resize method as used for the VGG feature extractor.

def main():

"""

Main function.

"""

# get C3D pretrained model

net = C3D()

net.load_state_dict(torch.load('c3d.pickle'))

net.cuda()

net.eval()

for video_path in os.listdir("./dataset"):

vid = visionio.read_video("./dataset/"+video_path)[0]

vid_features = torch.zeros(((len(vid)+7)//8,4096))

for i in range(8,len(vid)-7,8):

clip = vid[i-8:i+8]

clip = torch.permute(clip, (0, 3, 1, 2))

# resize clip

clip = transforms.Resize(224)(clip)

# centrally crop (outputs 224x224 clip)

clip = fn.center_crop(clip, output_size=[224])

clip = torch.permute(clip, (1, 0, 2, 3)) # ch, fr, h, w

clip = clip[None, :]

clip = clip.float()

clip = clip.cuda()

with torch.no_grad():

vid_features[i//8] = net(frame)

torch.save(vid_features,"./C3D-features/"+video_path+".pt")

torch.cuda.empty_cache()

Creating a custom data loader:

In order to utilize these generated features, we wrote a custom data loader to package our features, timestamps, and annotations to our model to provide our ground truth data. This involved splitting based on train and test data, and reading from reference files in order to correctly group video duration times, annotations, and timestamps. As a final step of the data loader, we wrote a feature loader function that loaded in each of the featurized images onto the GPU for processing.

""" Dataset loader for the AnimalKingdom dataset """

import os

import json

import h5py

import torch

from torch import nn

import torch.nn.functional as F

import torch.utils.data as data

import torchtext

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from . import average_to_fixed_length

from core.eval import iou

from core.config import config

import numpy as np

class AnimalKingdom(data.Dataset):

vocab = torchtext.vocab.pretrained_aliases["glove.6B.300d"]()

vocab.itos.extend(['<unk>'])

vocab.stoi['<unk>'] = vocab.vectors.shape[0]

vocab.vectors = torch.cat([vocab.vectors, torch.zeros(1, vocab.dim)], dim=0)

word_embedding = nn.Embedding.from_pretrained(vocab.vectors)

def __init__(self, split):

super(AnimalKingdom, self).__init__()

self.vis_input_type = config.DATASET.VIS_INPUT_TYPE

self.data_dir = config.DATA_DIR

self.split = split

self.vid_to_idx = {}

self.features = None

annotations = []

# adding annotations, start/end to list

with open(os.path.join(self.data_dir, '{}.txt'.format(split)),'r') as f:

for l in f:

hashtag = l.split("##")

sentence = hashtag[1].rstrip('\n')

vid, start,end = hashtag[0].split(" ")

annotations.append((vid,float(start),float(end),sentence))

vid_to_durations = {}

# adding durations to info

with open(os.path.join(self.data_dir,'ak_vg_duration.json'),'r') as f:

video_durations = json.load(f)

for pair in video_durations:

vid_to_durations[pair["vid"]] = pair["duration"]

anno_pairs = []

# adding all of the information into annotation pairs

for vid,start,end,sentence in annotations:

duration = vid_to_durations[vid]

if start < end:

anno_pairs.append(

{

'video': vid,

'duration': duration,

'times':[max(start,0),min(end,duration)],

'description':sentence,

}

)

self.annotations = anno_pairs

def __getitem__(self, index):

video_id = self.annotations[index]['video']

gt_s_time, gt_e_time = self.annotations[index]['times']

sentence = self.annotations[index]['description']

duration = self.annotations[index]['duration']

word_idxs = torch.tensor([self.vocab.stoi.get(w.lower(), 400000) for w in sentence.split()], dtype=torch.long)

word_vectors = self.word_embedding(word_idxs)

visual_input, visual_mask = self.get_video_features(video_id)

# Time scaled to same size

if config.DATASET.NUM_SAMPLE_CLIPS > 0:

# visual_input = sample_to_fixed_length(visual_input, random_sampling=True)

visual_input = average_to_fixed_length(visual_input)

num_clips = config.DATASET.NUM_SAMPLE_CLIPS//config.DATASET.TARGET_STRIDE

s_times = torch.arange(0,num_clips).float()*duration/num_clips

e_times = torch.arange(1,num_clips+1).float()*duration/num_clips

overlaps = iou(torch.stack([s_times[:,None].expand(-1,num_clips),

e_times[None,:].expand(num_clips,-1)],dim=2).view(-1,2).tolist(),

torch.tensor([gt_s_time, gt_e_time]).tolist()).reshape(num_clips,num_clips)

# Time unscaled NEED FIXED WINDOW SIZE

else:

num_clips = visual_input.shape[0]//config.DATASET.TARGET_STRIDE

raise NotImplementedError

# torch.arange(0,)

item = {

'visual_input': visual_input,

'vis_mask': visual_mask,

'anno_idx': index,

'word_vectors': word_vectors,

'duration': duration,

'txt_mask': torch.ones(word_vectors.shape[0], 1),

'map_gt': torch.from_numpy(overlaps),

}

return item

def __len__(self):

return len(self.annotations)

def get_video_features(self, vid):

# load vgg features from video into torch tensor

features = torch.load(os.path.join(self.data_dir, "c3d-pytorch/vgg-features/"+vid+".mp4.pt"))

if config.DATASET.NORMALIZE:

features = F.normalize(features,dim=1)

vis_mask = torch.ones((features.shape[0], 1))

return features, vis_mask

Baseline Results:

Charades-STA

Charades-STA [6] is a new dataset built on top of Charades by adding sentence temporal annotations. The Charades dataset is composed of 9,848 videos of daily indoors activities with an average length of 30 seconds.

| Method | Rank1@0.5 | Rank1@0.7 | Rank5@0.5 | Rank5@0.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool | 40.94 | 22.85 | 83.84 | 50.35 |

| Conv | 42.80 | 23.25 | 80.54 | 54.14 |

ActivityNet Captions

The ActivityNet Captions dataset [5] is built on ActivityNet v1.3 which includes 20k YouTube untrimmed videos with 100k caption annotations. The videos are 120 seconds long on average.

| Method | Rank1@0.3 | Rank1@0.5 | Rank1@0.7 | Rank5@0.3 | Rank5@0.5 | Rank5@0.7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool | 59.45 | 44.51 | 26.54 | 85.53 | 77.13 | 61.96 |

| Conv | 58.75 | 44.05 | 27.38 | 85.65 | 76.65 | 62.26 |

TACoS

The TACoS [7] dataset consists of 127 videos of household tasks and cooking with multi-sentence descriptions.

| Method | Rank1@0.1 | Rank1@0.3 | Rank1@0.5 | Rank5@0.1 | Rank5@0.3 | Rank5@0.5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool | 47.59 | 37.29 | 25.32 | 70.31 | 57.81 | 45.04 |

| Conv | 46.39 | 37.29 | 25.17 | 74.46 | 56.99 | 44.24 |

Transfer learning for Animal Kingdom:

As discussed above, we decided to apply transfer learning on the Animal Kingdom [8] dataset. This dataset consists of 50 hours of annotated videos to localize relevant animal behavior segments in long videos for the video grounding task, which correspond to a diverse range of animals with 850 species across 6 major animal classes.

The ActivityNet pretrained model used compressed C3D features that were difficult to generate and work with given the time constraint of the project, so we decided to use the TACoS and Charades-STA models to perform video-grounding.

To generate the data, we first featurized the Animal Kingdom dataset into C3D features to align it with the TACoS pretrained model, and VGG features to align it with the Charades-STA pretrained model. We decided to first run the Animal Kingdom dataset on the TACoS and Charades-STA pretrained weights to get a baseline of performance before attempting to fine-tune the models.

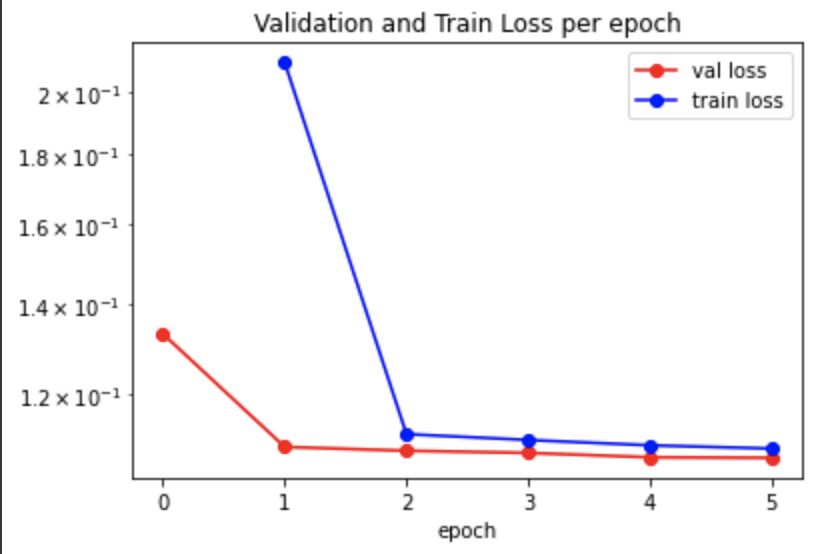

After generating the results seen below, we decided to fine-tune on Charades-STA for two reasons. The first, practically speaking, was because of our limited budget. We ran into many issues with GPU memory, RAM, and overall computation power when trying to run substantial training with TACoS. The second was because TACoS is purely about household tasks and cooking videos, while Charades-STA involves a much broader set of tasks, and also that TACoS is a much smaller dataset than Charades-STA. Thus, we decided to fine-tune our model on Charades-STA pretrained weights.

TACoS Pre-Trained Model on Animal Kingdom: |Method |Rank1@0.1 |Rank1@0.3 |Rank1@0.5 |Rank1@0.7 |Rank5@0.1 |Rank5@0.3 |Rank5@0.5 |Rank5@0.7| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |Pool|33.21|15.87|7.66|2.61|64.95|40.01|24.83|11.55| |Conv|33.05|17.12|7.90|3.04|72.02|45.91|26.94|11.36|

Charades-STA Pre-Trained Model on Animal Kingdom: |Method |Rank1@0.1 |Rank1@0.3 |Rank1@0.5 |Rank1@0.7 |Rank5@0.1 |Rank5@0.3 |Rank5@0.5 |Rank5@0.7| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |Pool|22.89|11.36|4.99|2.03|84.37|55.53|29.98|12.80| |Conv|30.91|16.70|6.91|2.32|71.43|47.24|24.42|11.04|

Transfer learning on Charades-STA |Method |Rank1@0.1 |Rank1@0.3 |Rank1@0.5 |Rank1@0.7 |Rank5@0.1 |Rank5@0.3 |Rank5@0.5 |Rank5@0.7| — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |Conv|53.16|24.64|11.42|4.89|81.45|50.00|31.35|17.71|

Discussion

TACoS pretrained weights work better for Rank1 while Charades pretrained weights work better for Rank5 (w/o finetuning)

Though TACoS is a dataset centered around cooking videos, it performed higher than Charades without fine-tuning on Rank1 observations. One possible explanation for this is due to the features used as input. TACoS uses C3D, which are convolutional 3D features, that might help capture spatio-temporal relations better than a traditional convolutional network such as VGG that captures spatial-visual features. Another possible humorous hypothesis is that there is some overlap between the animals being cooked for eating in TACoS and the (alive) animals in Animal Kingdom.

However, we see some benefits in using a more general dataset such as Charades in the Rank5 observations, which perform better than TACoS. Though TACoS enjoys a slight edge in terms of Rank1 observations, Charades seems to perform better generally speaking in being able to identify the clip moment in an initial set of guesses, indicating the model might be an overall more robust model. It is also possible that Charades action labels for humans are analogous to animal actions, which helps boost the model in general.

Possible Room for Improvement

As we used a Charades-STA model that takes input as VGG features and also used VGG features for our Animal Kingdom dataset, this might lead to some performance losses. VGG only captures spatial-visual features and operates on a single frame, while other models like C3D may be able to better capture spatial-temporal features. When we compare the Charades-STA model to the ActivityNet model based on C3D features, we can see performance benefits in using the ActivityNet model, some of which is likely due to using spatial-temporal features. In addition, VGG, though not obsolete, is an older model, and using a newer model might better be able to capture the video features.

The second possible studies for improvement are around our word embedding process. Though our work has focused on the visual aspect of 2D-TAN, the query process is arguably just as important. To generate the embeddings for the queries, the queries are passed through a Word2Vec model. The issue with this is that there is possibly (and almost certainly) some amount of semantic loss from using this model to embed these queries, particularly in reference to Animal Kingdom, with its diverse 850 species of animals. Word2Vec is known to have an inability to handle unknown or out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words, and with this number of species, the likelihood of rare animal names and species is higher. A possible hypothesis/scenario would be that Animal Kingdom has very low probability/out of vocabulary words with rare species of animals and the word embeddings generated by Word2Vec may be random or contain low semantic meaning. Then, when 2D-TAN tries to map the query to a location, it has difficulty mapping a low semantic query to a specific location. Thus, to improve the performance, using a better language model to create features from the input queries may show some performance increases when training the models. Or, fine-tuning a word embedding model like Word2Vec on an animal-focused corpus might help the model better “understand” the different queries and lead to less semantic loss.

It is also important to note that Charades-STA consists of exclusively indoor scenes while AnimalKingdom consists almost entirely of outdoor scenes of wild animals. Since outdoor clips may have brighter lighting on average, and very different types of scenery, there is a difference in domain which could further explain poor results before applying any transfer learning.

Why Transfer Learning Works:

Overall, the Video Grounding tasks for Charades-STA and AnimalKingdom are similar enough so pretrained knowledge from Charades-STA is adaptable to AnimalKingdom. In the conv model which we fine tuned, the weights that are updated during transfer learning are held in the stacked convolution which is used to extract clip features, the final convolutional net, and the last fully connected layer.

We hypothesize that the tuning of the stacked convolution plays an insignificant role in improving the model, as it is more of a “clip summary” mechanism which should hold up relatively well across different domains.

So, it is likely that performance increases mainly due to large domain differences becoming accounted for in the final convolutional net and the subsequent fully connected layer which become better at learning overall structure as well as temporal dependencies for this unique domain.

Ablation Study: Stacked Convolutional Layers vs Pooling Layers

One ablation study we ran as a consequence of replicating the results was comparing the results of using a convolutional layer vs a pool layer in the 2D-TAN model. We came to similar conclusions as the authors, that there were little to no performance benefits to using convolutional layers despite the extra cost and time required for convolutional layers as compared to pooling layers. Comparing ActivityNet, Charades-STA, and TACoS, ActivityNet performs slightly better with convolutional layers, TACoS performs slightly better with pooling layers, and Charades-STA performs similarly, depending on the metric. Thus, based on the baseline results, convolutional layers seem not to be worth the extra cost.

However, we came to an interesting finding after applying the same study to our application of the two baseline models to Animal Kingdom, overall both perform better using stacked convolutional layers. This indicates that the extra cost was not in vain, and that the additional computation and cost of learning convolutional parameters causes additional robustness in the model, when applying these baseline models to other relatively unseen domains. Further study will need to be done in this area, as time did not permit us to run more extensive ablation studies on this specific issue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we analyzed one prominent video grounding model, 2D-TAN. In addition to confirming its strong performance on pre-used datasets, we introduced a novel dataset, Animal Kingdom, to analyze the extensibility of the 2D-TAN model to a new video domain. Our results showed that 2D-TAN is a highly performant and tunable backbone to perform video grounding on a wide array of video domains. Further analysis is proposed in using alternate input features to 2D-TAN, such as more recent models that encode spatial-temporal features, and also training a base model from scratch on Animal Kingdom. Though we suggest more studies on 2D-TAN parameters and possible layers, our results indicated 2D-TAN is a robust structure for video grounding, able to take small amounts of transfer-learning and fine-tuning to quickly scale 2D-TAN across novel applications.

References

[1] Zhang, Songyang, et al. “Learning 2d Temporal Adjacent Networks for Moment Localization with Natural Language.” ArXiv.org, 26 Dec. 2020, https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.03590.

[2] Hendricks, Lisa Anne, et al. “Localizing Moments in Video with Natural Language.” ArXiv.org, 4 Aug. 2017, https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.01641.

[3] Zhang, Da, et al. “Man: Moment Alignment Network for Natural Language Moment Retrieval via Iterative Graph Adjustment.” ArXiv.org, 17 May 2019, https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.00087.

[4] Wang, Limin, et al. “Temporal Segment Networks: Towards Good Practices for Deep Action Recognition.” ArXiv.org, 2 Aug. 2016, https://arxiv.org/abs/1608.00859.

[5] F. C. Heilbron, V. Escorcia, B. Ghanem and J. C. Niebles, “ActivityNet: A large-scale video benchmark for human activity understanding,” 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 2015, pp. 961-970, doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298698.

[6] Gao, Jiyang, et al. “Tall: Temporal Activity Localization via Language Query.” ArXiv.org, 3 Aug. 2017, https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.02101.

[7] Regneri, Michaela, et al. “Grounding Action Descriptions in Videos.” Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, vol. 1, 2013, pp. 25–36., https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00207.

[8] Ng, Xun Long, et al. “Animal Kingdom: A Large and Diverse Dataset for Animal Behavior Understanding.” 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2022, https://doi.org/10.1109/cvpr52688.2022.01844.