On the Evolution of Reasoning in Large Language Models

Large language models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable performance across a wide range of tasks, increasingly attributed to their ability to perform multi-step reasoning. This paper surveys the evolution of reasoning in LLMs, organizing the literature into four main categories: internal representations, structured prompting, reinforcement learning, and supervised fine-tuning. We explore how reasoning can emerge from scale, be encouraged through prompt design, be enhanced through interaction and reward signals, and be explicitly taught through labeled reasoning traces. We discuss the advantages, limitations, and trade-offs of each method and analyze how these strategies influence model performance, generalization, interpretability, and scalability. Together, these advances reflect a growing understanding of how to build LLMs that not only generate fluent text but also reason through complex problems in a structured and effective manner.

- Introduction

- Internal Representations

- Structured Prompts for Multi-Step Reasoning

- Reasoning by Reinforcement Learning

- Supervised Learning From Reasoning Traces

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Large language models (LLMs) have become increasingly sophisticated for complex tasks. One of the key mechanisms by which this has emerged is through a technique called ‘reasoning’ whereby an LLM, like a human, will walk through the steps of a problem before outputting its response. In practice, various implementations of reasoning have demonstrated remarkable improvements in various complex benchmarks, including sophisticated coding and mathematical tasks.

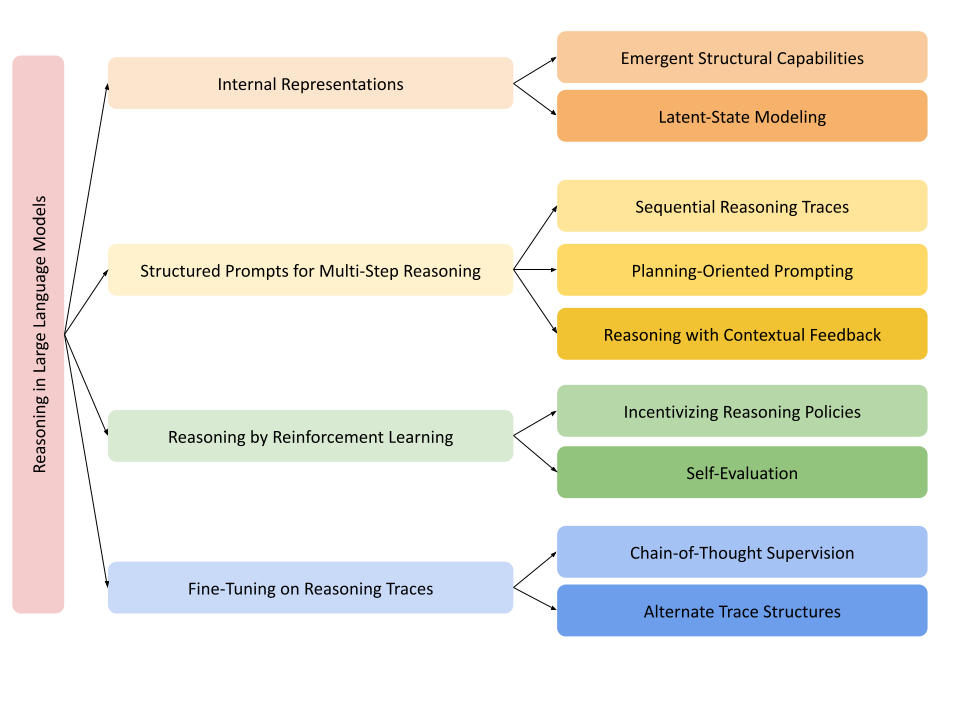

This article is organized using the following taxonomy. We cover four key sections: 1) Internal Representations, 2) Structured Prompts for Multi-Step Reasoning, 3) Reasoning by Reinforcement Learning, and 4) Fine-Tuning on Reasoning Traces.

Fig 1: Taxonomy of Reasoning Approaches

Internal Representations

As language models become more complex, research has identified that LLMs are able to perform sophisticated reasoning tasks without explicit instruction or task-specific training. In fact, reasoning ability can emerge naturally from the scale of a model’s architecture and structured instructions or become represented as latent computations within the model’s internal representations.

Emergent Structural Capabilities

Chain-of-Thought

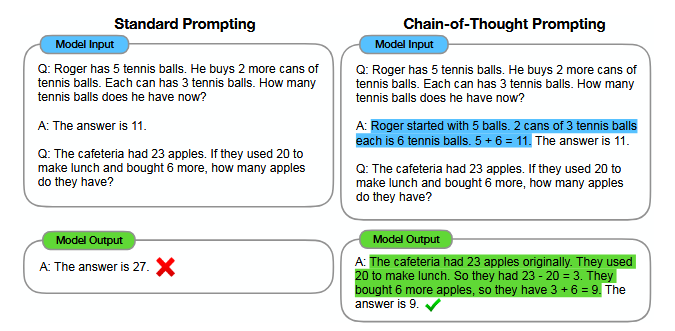

Perhaps the most fundamental approach to reasoning is through a prompt structure called “Chain-of-Thought” (CoT) prompting. Introduced by Wei et al., CoT prompting involves demonstrating several examples of reasoning in the text input to the LLM which encourages the model to follow the pattern in their response. They identify that with this pattern, large-scale models (at least 100 billion parameters), can correctly perform arithmetic, commonsense, and symbolic reasoning [10].

Fig 2: Chain-of-Thought Prompting

Their approach is both simple and accessible. Without modifying the underlying weights of the model, this “prompt engineering” approach helps models reason so long as the user prompts it in the correct direction. Wei et al. find that even when the test examples were out-of-domain (OOD) or otherwise different from the examples in the prompt, CoT helped the model generalize its reasoning process by harnessing the models priors obtained from the internet-scale training set [10].

However, CoT is not without drawbacks. First, it increases the number of tokens generated to answer a query, making the latency to get a solution longer. This is especially relevant for simple queries, like basic fact look-ups, where reasoning is not necessary. Also, CoT is sensitive to the quality of the provided examples in the prompt, making reproducibility and reliability an issue.

Nonetheless, the overall format for CoT has become highly influential formed the basis of many other approaches for language model reasoning.

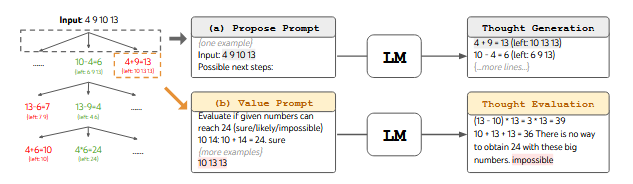

Zero-Shot Prompting

One such approach is zero-shot prompting, proposed by Kojima et al., where a model is encouraged to perform this reasoning without including any examples [6]. They observe that, without any examples, LLMs perform poorly with multi-step reasoning tasks. While CoT addresses this, accumulating the examples and explaining rationale for the examples is costly and takes up precious tokens in the context window of the model. Kojima et al.’s insight was that a simpler way to encourage models to reason was to simply add the phrase “Let’s think step by step”. While this approach is not as effective as few-shot CoT prompting, it performs dramatically better than the prompt where this phrase was omitted for arithmetic, commonsense, and symbolic reasoning tasks [6].

Fig 3: Zero-Shot Prompting

Latent State Modeling

Latent Reasoning Optimization

Considering that modern LLMs have been pre-trained on practically humanity’s entire history of written text, many surmise that they already inherently have the ability to reason and it is only a matter of fine-tuning the model to develop latent representations that encourage the generation of reasoning. Recent work demonstrates that this can be done entirely by LLM in a process called ‘self-rewarding’ [1].

Chen et al. introduce “Latent Reasoning Optimization” (LaTRO), which explores this exact premise. When fine-tuning on specific question-answering (QA) datasets like GSM8K, their model samples various reasoning paths, called rationales, computes a log-likelihood for that rationale leading to the correct answer, and updates its parameters to encourage the generation of the best rationale without deviating too much from the original pre-trained model (for regularization). At inference time, the model is able to generate latent representations of the necessary reasoning steps [1].

Importantly, this “self-rewarding” loop does not require external feedback or additional labeling. This allows it to scale much better than mechanisms like reinforcement learning through human feedback (RLHF), which require costly, human-labeled responses. Chen et al. also mention that LaTRO outperforms supervised fine-tuning (SFT) approaches where a human provides a ‘gold rationale’, likely due to improved exploration and robustness. However, this fully automated approach has major limitations, especially with respect to human preference. While RLHF and SFT are grounded in outputs that a human would prefer, Chen et al. explain that LaTRO may not always align with human judgment, especially in tasks without a single correct answer, like creative applications. In general, they note that LaTRO struggles to scale tasks such as math, science, and logic [1].

Chain of Continous Thought

Another approach for reasoning in the latent space is presented by Hao et al. in their paper “Training Large Language Models to Reason in a Continuous Latent Space” [4]. Their approach, “Chain of Continuous Thought” (COCONUT), breaks a key limitation in the fundamental CoT approach by building this chain in the latent space as opposed to natural language. During reasoning, COCONUT does not produce the next token, instead directly feeding forward the last hidden state of the neural network as a “thought vector” which summarizes the model’s reasoning. In this way, Hao et al. explain that COCONUT need not commit to a single chain as in CoT, instead enabling a breadth-first search-like approach to keep many reasoning paths alive represented in their latent thought vector [4].

To train such a model, Hao et al. use a multi-stage curriculum. They start with regular CoT language data to build a foundation for reasoning, and gradually replace the start of the reasoning change with a thought vector until the entire process is done in the latent space. This allows them to keep the causal autoregressive structure of decoder-only transformers while also enabling the model to “internalize” initial steps (which tend to be simpler) before moving on to the rest [4].

In their evaluation, Hao et al. find that COCONUT had similar or better performance than existing CoT methods while generating significantly fewer tokens—up to an order of magnitude less. They also determined there were similar scaling laws with the number of “thoughts” in the reasoning process; chaining together more thought vectors meaningfully improved the performance on mathematical, logical, and planning-heavy benchmarks. Yet, despite its performance, it still depends heavily on supervised CoT training data, loses interpretability by hiding its reasoning in latent vectors, and, due to the sequential nature of hiding reasoning steps in training, is difficult to parallelize [4]. This makes it so COCONUT may be more difficult to scale with more data compared to other approaches.

Structured Prompts for Multi-Step Reasoning

Beyond just CoT prompting, there exist many alternative approaches in the literature to encourage models towards reasoning responses. Many of these techniques utilize creative manipulations of the prompt to rephrase reasoning as different tasks that incentivize LLMs to reason in specific, nuanced ways.

Sequential Reasoning Traces

One of the simplest ways to structure a prompt for sequential reasoning is to explicitly include a sequence of step. CoT, an approach discussed previously uses exactly this approach to guide the model to imitate this in their response. Then, the trace of reasoning steps ideally helps the model reach the correct answer [10].

Self-Consistency

A key limitation with CoT is this notion of greedy decoding with the decoder-only transformer architecture. That is, the model picks the most likely word at each step, often leading to reasoning paths which tunnel in on incorrect paths. To address this, Wang et al. describe a new method called “Self-Consistency” where multiple rationales and their corresponding answers are generated. Then, the actual answer is the most common, or consistent, outcome. They surmise that if many different ways of thinking lead to the same answer, then that answer is more likely to be correct [9].

While this has many of the same benefits of CoT with the extra strength in numbers, this approach suffers from dramatic increases in latency. Wei et al. explain that the method does achieve accuracy gains of up to nearly 20% on reasoning benchmarks compared to vanilla CoT, they obtain this by sampling responses from 20-40 outputs per prompt [9]. Moreover, their approach has no mechanism to intelligently search for the correct reasoning and instead assumes the most common answer is correct.

Planning-Oriented Prompting

Another approach to address the greedy decoding issue with vanilla CoT is to design a structure by which an LLM can plan its approach at each step. Then, instead of diving into a single line of reasoning, an LLM might consider various different paths at each step and, using some external code or evaluation, choose to reason in the most promising way.

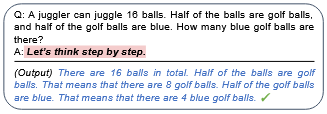

Tree-of-Thoughts

One paradigm which implements this is the Tree-of-Thoughts (ToT) framework, first described by Yao et al.. In their approach, they structure reasoning as a tree-search problem. Using an LLM, they can generate steps of reasoning which are then evaluated by the LLM as promising or not. This process is repeated as many steps as necessary to generate a final response [11].

Fig 4: Tree-of-Thoughts Prompting

Yao et al. observe that ToT dramatically outperforms CoT on tasks which require non-trivial planning like the Game of 24 and Mini Crosswords. In particular, GPT-4 with CoT was only able to solve 4% of Game of 24 tasks, while ToT could solve 74% of the questions. Perhaps more interesting is that this approach generalizes to tasks without concrete solutions like creative writing [11].

The downsides of ToT are unsurprising. Generating and evaluating many different options requires significantly more prompts that CoT and zero-shot reasoning, leading to much slower reasoning. Moreover, the evaluation signal for which thought is most effective is based entirely on the LLM itself, making it noisy and sensitive to prompt design. Of course, the actual implementation details for making this function are significantly more complex than previous approaches, especially with regards to the number of structure prompts to design.

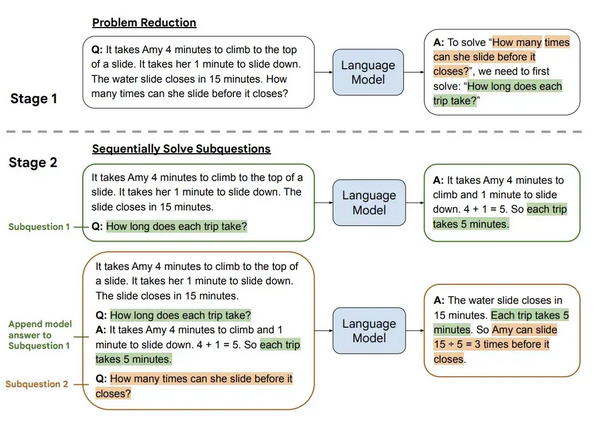

Least-to-Most Prompting

Another planning approach is presented by Zhou et al. where a complex problem is broken into subproblems which can be solved in order and used as building blocks to solve the full problem. This approach, called Least-to-Most prompting is a two-stage process: 1) the model is prompted with few-shot prompting for problem decomposition, and 2) each subproblem is solved and serves as context for the next step. In this way, the reasoning for the problem is built bottom-up, allowing the model to build a correct foundation for a larger, more complex problem [13].

Fig 5: Least-to-Most Prompting

Importantly, this addresses an issue with CoT prompting when the test problem is significantly more complex than the in-context examples. Instead of following patterns in the examples, Least-to-Most solves this by teaching the structure behind reasoning, and generalizes better to deeper or more compositional problems. Specifically, Least-to-Most yields small gains over standard CoT in arithmetic problems, but yields dramatically improved performance on the SCAN benchmark (99.7% vs. 16%), a repository of tasks to map sentences to action sequences [13].

Its limitations are almost identical to vanilla CoT: the output is sensitive the prompt design, prompts are non-transferrable between domains, and the approach is still fundamentally in-context learning. This means that gains are ephemeral and require re-prompting to observe similar results between sessions.

Reasoning with Contextual Feedback

Many applications require the concept of an “agent” which can take actions in a particular environment. For example, an LLM might want to search through a Wikipedia article or click on web pages to fulfill their task. This new environment becomes contextual feedback that guides future reasoning steps.

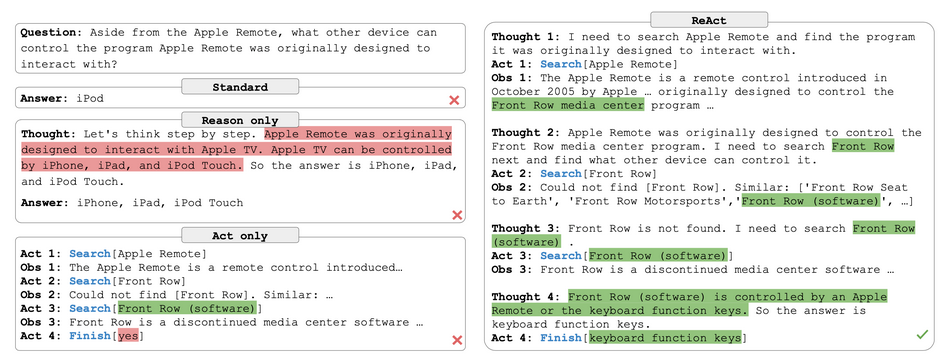

ReAct

Yao et al. discuss the premise that between any two actions, a human agent may need to reason in language to track progress, handle exceptions, and/or adjust the current plan based on context in the environment. They hypothesize that LLMs can benefit from the same paradigm where an LLM can generate reasoning traces based on prior reasoning and observations from an environment. Then, they may take better actions in this environment which continues this feedback loop [12].

They describe a particular example where an LLM is asked a question about Apple Remotes. With only reasoning, the LLM suffers from misinformation that is not grounded in truth provided by an external environment. Similarly, with only actions, the model can only search for answers and therefore lacks the reasoning necessary to synthesize the searched information into a coherent answer [12].

Fig 6: ReAct Example

This approach combines the best between reasoning and acting and gives LLMs a grounded reality to base their reasoning on. Moreover, Yao et al. observe that the greedy decoding from the LLMs lacks enough exploration and can get stuck in reasoning loops, repeating the same thoughts or actions. They explain that this makes it difficult for ReAct to recover from poor initial reasoning [12].

Reasoning by Reinforcement Learning

Several works have opted to tackle this issue of reasoning beyond modifying prompts and instead using reinforcement learning (RL) to incentivize reasoning in particular ways. By explicitly rewarding effective reasoning, measured by correctness, consistency, success, etc., RL-based approaches have seen strong success. Through interacting with environments, tools, or evaluators, models can refine their strategies through feedback, enabling more robust behavior than purely supervised approaches. Moreover, by modeling success through a reward instead of similarity to a desired outcome, RL-based approaches tend to avoid the scaling limitations that come with SFT.

Incentivizing Reasoning Policies

DeepSeek-R1

DeepSeek AI et al.’s paper was the first open work to demonstrate that reasoning capabilities in LLMs can emerge from reward-driven training alone. Their initial approach, using only RL to fine-tune a base model, DeepSeek-V3, included rewards for accuracy and correctly formatting their response to include <think> tags in the response. This model, called DeepSeek-R1-Zero, implicitly learns many techniques which other works explicitly describe or implement. Behaviors like CoT reasoning, self-verification, and re-evaluation are all emergent properties of DeepSeek-R1-Zero [3].

Naturally, there are limitations with a purely RL-based approach dependent on emergent learning. Importantly, DeepSeek AI et al. observe that DeepSeek-R1-Zero tends to include non-sensical or otherwise unhelpful reasoning with the <think> tags. To address this, they describe a multi-stage RL pipeline they used to develop their superior reasoning model, DeepSeek-R1.

DeepSeek-R1’s post-training starts with SFT using high-quality CoT responses. Only once the model has learned what coherent CoT rationale looks like, RL is used to incentivize reasoning and boost its accuracy. Then, through a process called “rejection sampling”, only the best generations of the model are kept and used as new training data for multiple rounds of SFT [3].

They show that using RL to unlock autonomous reasoning in LLMs, DeepSeek-R1 is competitive against other LLMs against many sophisticated benchmarks like competitive mathematics and advanced programming. Yet, the DeepSeek AI researchers reveal that, compared to its base model, DeepSeek-V3, DeepSeek-R1 struggles with interactive dialogue or agent-based tasks [3]. Perhaps its specialization in reasoning has limited its flexibility for general use cases.

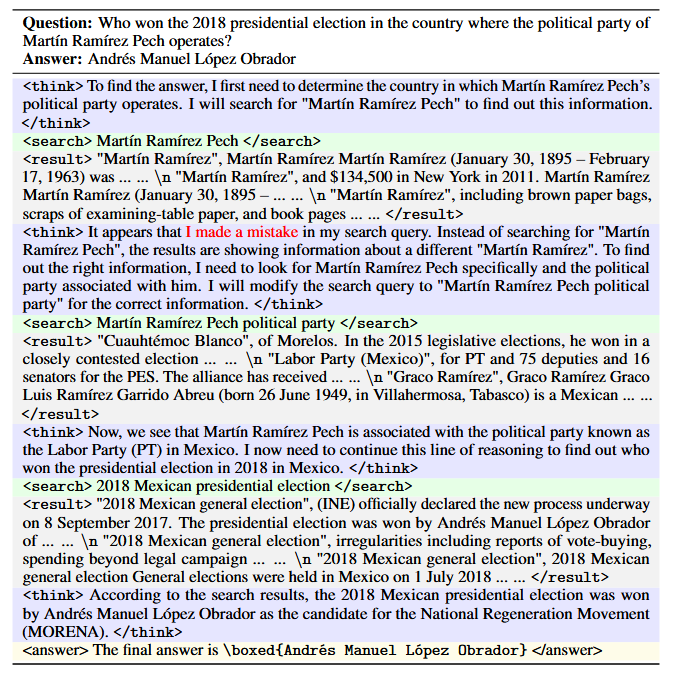

ReSearch

Another work focused on combining reasoning and actions (web searching) is ReSearch, introduced by Chen et al.. Using RL, the model can learn when to use reasoning and/or web searches through tags like <search>, <result>, <think>, and <answer>. The model is only rewarded for getting the correct answer and using the correct format, just like with DeepSeek-R1-Zero [2].

Under this approach, Chen et al. observe emergent capabilities like reflection and self-correction in the model’s output, enabling state-of-the-art (SotA) performance on multi-hop QA benchmarks, outperforming other baselines by up to 22%. In particular, although it was only trained on one of these benchmarks, MuSiQue, its performance generalized across other datasets like HotpotQA, 2WikiMultiHopQA, and Bamboogle [2].

Fig 7: ReSearch Example

Interestingly, ReSearch relies entirely on RL for its fine-tuning step. Future work could explore approaching the problem with a hybrid post-training step with both RL and SFT and evaluate its performance on the same benchmarks.

Self-Evaluation

Self-Evaluation is a convenient way for an LLM to improve its reasoning capabilities by leveraging a key benefit from RL: labeled data is not necessary to incentivize reasoning. Other works have approached self-evaluation to sample the most effective rationale paths, but in practice, self-evaluation can be utilized under an RL framework to learn a policy which encourages reasoning [1,9].

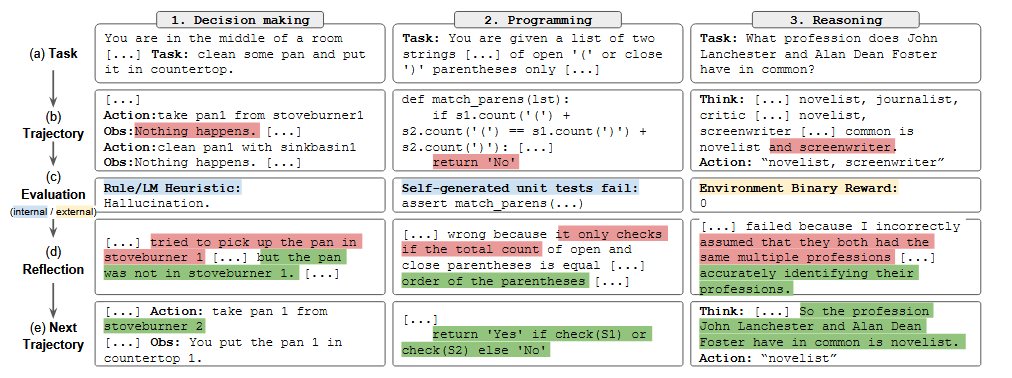

Reflexion

Shinn et al. create Reflexion, a method for improving LLMs by having the LLM generate its own feedback as a reward signal for RL. Yet, instead of traditional RL, Reflexion performs a form of language-native reward modeling whereby an actor model generates a response, the environment returns a scalar reward, and then a third self-reflection model translates the response and rewards into verbal advice. This advice is stored in an episodic memory module and used as additional context for future responses [8].

Fig 8: Reflexion Example

They evaluated Reflexion on sequential decision-making, reasoning, and programming benchmarks, demonstrating that compared to baselines such as ReAct or CoT, Reflexion was shown to improve performance by as much as 25%. However, as is common with many of these textual approaches, these self-reflections bloat the context window and could limit the amount of reflection possible. Moreover, the performance is highly dependent on the quality of the reflection. Finally, Shinn et al. explain that the reward function is task specific, so unlike other RL approaches, Reflexion is not as “plug-and-play” [8].

Supervised Learning From Reasoning Traces

Although reasoning was initially done through in-context prompting, supervised learning on these reasoning traces has emerged as a method to generate CoT-like outputs even without needing to manually prompt the model with few-shot prompting. By fine-tuning in this way, LLMs are exposed to complex reasoning approaches, enabling them to internalize these patterns and “learn” deductive and inductive reasoning.

Chain-of-Thought Supervision

LLM Self-Improvement

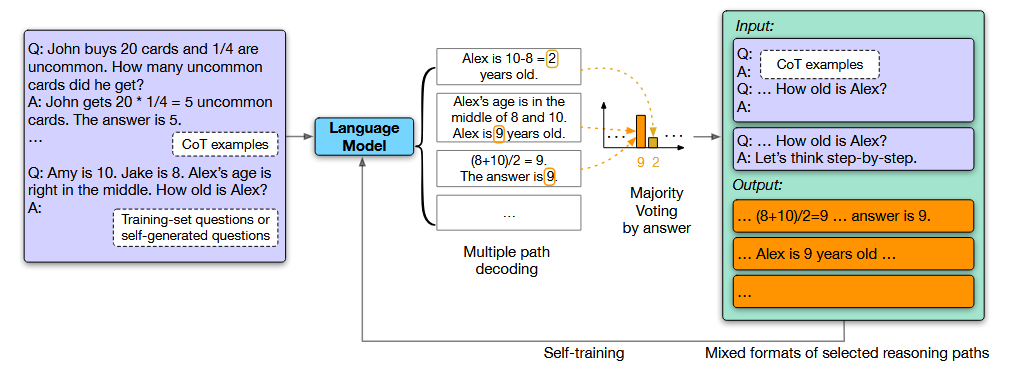

In Huang et al.’s work, they acknowledge that producing large, labeled datasets of reasoning traces to perform SFT is expensive and not scalable. Yet, they observe that such traces can be obtained automatically by repeated prompting an LLM and using self-consistency (majority vote) to automatically obtain high quality data. This pipeline, called Language Model Self-Improvement (LMSI) achieved SotA performance on many reasoning benchmarks, like ARCC, OpenBookQA, GSM8K, and more, all without using human-labeled data for SFT [5].

Fig 9: Language Model Self-Improvement Example

In addition to achieving outstanding performance on training tasks, benchmarking on unseen tasks, like on StrategyQA and MNLI showed that LMSI could be used to improve out-of-domain reasoning as well. That is, LMSI enables more general forms of reasoning that function in a broad variety of seen and unseen tasks. Additionally, although LMSI is especially potent for large models, distillation to smaller models is shown to maintain much of the performance. Yet, relying on self-consistency for correctness is imperfect and can create emergent failures in domains which depend on factual accuracy like law or medicine.

Alternate Trace Structures

Although CoT is by far the most common and broadly applicable form of reasoning, there exists a body of work exploring alternate strategies to encourage reasoning in language models. These methods tend to follow more structured formats, as opposed to the generality of CoT, and yield meaningful performance improvements in particular tasks or domains.

Additional Logic Training

Morishita et al. identify that LLMs fail at generalizable reasoning in deductive logic tasks, especially as a result of low representation of logical reasoning in the training corpus. As a result, they propose Additional Logic Training (ALT) to fine-tune LLMs on synthetically generated logical reasoning samples from their new logical reasoning dataset, Formal Logic Deduction Diverse (FLDDx2), focused on symbolic logic theory. They generate these samples using natural language templated (e.g. If F, then G), and construct examples using 4 design principles: 1) Reasoning with unknown facts, 2) Including illogical examples, 3) Diverse reasoning rules, and 4) Diverse linguistic expressions. The goal of these principles is to allow the LLM to generalize beyond memorized content, to prevent overgeneralization, to improve the coverage of all rules, and to improve linguistic robustness respectively [7].

They evaluate this on many benchmarks from logical reasoning, math, programming, and natural language inference, finding that all domains are improved with ALT, especially in logical reasoning which found a 30 point improvement. However, it is critical to note that the logical reasoning ability is only in reasoning, and has no bearing in real facts. That is, ALT does not improve tasks which depend on knowledge, but can improve an LLMs ability to reason about existing knowledge.

Conclusion

In this survey, we explored the evolution of reasoning in LLMs and examined the process by which emergent reasoning capabilities were found in LLMs and the modern strategies by which this reasoning can be harnessed in more automatic and sophisticated ways.

Altogether, the evolution of reasoning in LLMs is based on a rich interplay of prompting, post-training, and architectural design strategies, each offering different trade-offs between interpretability, latency, generalization, and scalability. Future work should analyze how these approaches can be combined and augmented to enable LLMs to reason with both precision and flexibility, across domains and modalities.

References

[1] Haolin Chen, Yihao Feng, Zuxin Liu, Weiran Yao, Akshara Prabhakar, Shelby Heinecke, Ricky Ho, Phil Mui, Silvio Savarese, Caiming Xiong, and Huan Wang. Language models are hidden reasoners: Unlocking latent reasoning capabilities via self-rewarding, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.04282.

[2] Mingyang Chen, Tianpeng Li, Haoze Sun, Yijie Zhou, Chenzheng Zhu, Haofen Wang, Jeff Z. Pan, Wen Zhang, Huajun Chen, Fan Yang, Zenan Zhou, and Weipeng Chen. Research: Learning to reason with search for llms via reinforcement learning, 2025. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.19470.

[3] DeepSeek-AI et al. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning, 2025. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2501.12948.

[4] Shibo Hao, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, DiJia Su, Xian Li, Zhiting Hu, Jason Weston, and Yuandong Tian. Training large language models to reason in a continuous latent space, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2412.06769.

[5] Jiaxin Huang, Shixiang Shane Gu, Le Hou, Yuexin Wu, Xuezhi Wang, Hongkun Yu, and Jiawei Han. Large language models can self-improve, 2022. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.11610.

[6] Takeshi Kojima, Shixiang Shane Gu, Machel Reid, Yutaka Matsuo, and Yusuke Iwasawa. Large language models are zero-shot reasoners, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.11916.

[7] Terufumi Morishita, Gaku Morio, Atsuki Yamaguchi, and Yasuhiro Sogawa. Enhancing reasoning capabilities of llms via principled synthetic logic corpus, 2024. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2411.12498.

[8] Noah Shinn, Federico Cassano, Edward Berman, Ashwin Gopinath, Karthik Narasimhan, and Shunyu Yao. Reflexion: Language agents with verbal reinforcement learning, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.11366.

[9] Xuezhi Wang, Jason Wei, Dale Schuurmans, Quoc Le, Ed Chi, Sharan Narang, Aakanksha Chowdhery, and Denny Zhou. Self-consistency improves chain of thought reasoning in language models, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2203.11171.

[10] Jason Wei, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Maarten Bosma, Brian Ichter, Fei Xia, Ed Chi, Quoc Le, and Denny Zhou. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2201.11903.

[11] Shunyu Yao, Dian Yu, Jeffrey Zhao, Izhak Shafran, Thomas L. Griffiths, Yuan Cao, and Karthik Narasimhan. Tree of thoughts: Deliberate problem solving with large language models, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2305.10601.

[12] Shunyu Yao, Jeffrey Zhao, Dian Yu, Nan Du, Izhak Shafran, Karthik Narasimhan, and Yuan Cao. React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2210.03629.

[13] Denny Zhou, Nathanael Sch¨arli, Le Hou, Jason Wei, Nathan Scales, Xuezhi Wang, Dale Schuurmans, Claire Cui, Olivier Bousquet, Quoc Le, and Ed Chi. Least-to-most prompting enables complex reasoning in large language models, 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2205.10625.