Pretraining Multilingual Foundation Models

Multilingual pretraining in large language models (LLMs) may confer cognitive benefits similar to those observed in multilingual humans, including enhanced reasoning and cross-linguistic generalization. Models often learn better when exposed to linguistic diversity rather than monolingual data, but the optimal balance remains unclear. In this study, we systematically investigate the impact of multilingual exposure by training LLaMA 3.2-1B models on varying ratios of English-Chinese data, characterize the performance changes across multiple benchmarks, and find that 25% multilingual exposure yields optimal results—improving logical reasoning and code synthesis by up to 130% while preventing catastrophic forgetting, though with some trade-offs in fairness metrics.

Introduction

Human multilingualism is widely associated with enhanced cognitive flexibility, improved executive control, and a broadened conceptual repertoire [1,2]. Languages encode distinct semantic frameworks and cultural logics, granting multilingual individuals access to diverse cognitive strategies [3]. Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have prompted the question of whether similar benefits can emerge in artificial systems through multilingual pretraining.

Transformer-based LLMs have demonstrated strong performance across a wide spectrum of reasoning, generation, and inference tasks [4,5]. However, the potential impact of multilingual training on their cognitive alignment and generalization capacity remains underexplored. This work investigates whether multilingual exposure confers systematic benefits to LLMs in reasoning, fairness, and cross-linguistic generalization, and whether these effects are comparable to the cognitive advantages observed in multilingual humans.

Specifically, we examine whether multilingual pretraining improves logical and cognitive reasoning, introduces emergent capabilities relative to monolingual baselines, mitigates social bias, and enhances generalization to low-resource languages. We further address disparities in language representation by comparing the effects of multilingualism across high- and low-resource settings under matched data and model conditions.

Related Work

Multilingual pretraining has shown strong empirical gains across cross-lingual transfer, zero-shot inference, and comprehension tasks [6,7]. Studies such as “Language Models as Multilingual Chain-of-Thought Reasoners” [6] demonstrate that multilingual LLMs can engage in structured reasoning across multiple languages, often outperforming monolingual models on tasks requiring abstraction and inference. Bandarkar et al. introduced the Belebele benchmark, revealing systematic gains in comprehension for MLLMs exposed to linguistic diversity [7].

The underlying mechanism is often attributed to cross-lingual knowledge transfer, wherein shared representations across languages allow models to generalize from high-resource to low-resource settings. Large-scale parallel corpora, such as WikiMatrix [8] and the UN Parallel Corpus [9], have been instrumental in supporting these findings. Further, reinforcement learning and instruction-tuning methods have revealed emergent capabilities in multilingual settings [5], analogous to transfer learning and conceptual blending in human cognition [1,2].

Despite these advances, key open questions remain. In particular, it is unclear to what extent the observed gains are attributable to multilingualism itself, rather than confounding factors such as total data scale, domain overlap, or token distribution. Furthermore, continual pretraining techniques—though widely adopted—have not been systematically evaluated in multilingual contexts for their impact on reasoning or fairness.

Our work seeks to isolate the causal effect of multilingual exposure under controlled conditions. We pretrain LLaMA 3.2–1B models on a balanced parallel corpus using carefully tuned sampling ratios and evaluate them on standard benchmarks for reasoning, fairness, and multilingual generalization.

Experimental Design

Model and Pretraining

We use the LLaMA 3.2–1B architecture, a compact, decoder-only transformer model pretrained primarily on English. All models are trained from the same initialization using full-parameter finetuning and identical hyperparameters. Pretraining is conducted using DeepSpeed (Stage 3), with 1 epoch over our custom multilingual datasets, employing gradient checkpointing and fused AdamW optimization.

model_name_or_path: meta-llama/Llama-3.2-1B

learning_rate: 2e-5

num_train_epochs: 1.0

cutoff_len: 2048

gradient_accumulation_steps: 8

per_device_train_batch_size: 8

warmup_ratio: 0.15

lr_scheduler_type: cosine

bf16: true

tf32: true

This consistent configuration ensures that observed differences in performance can be attributed to variations in multilingual exposure rather than architectural or training changes.

Language Splits

We divide our training data into two sets:

| High-resource (Set A) | Low-resource (Set B) |

|---|---|

| Chinese (zh) | Farsi (fa) |

| Hindi (hi) | Swahili (sw) |

| Arabic (ar) | Bengali (bn) |

| Spanish (es) | Yoruba (yo) |

Set A consists of widely resourced languages with substantial parallel corpora. Set B comprises lower-resourced languages with less digital representation. This division allows us to assess the differential impact of multilingual training across language strata.

Data Source and Preprocessing

We use the ParaCrawl English–Chinese v1.0 dataset [10], a large-scale, web-mined corpus with approximately 14 million aligned sentence pairs. ParaCrawl was selected for its breadth of domains, sentence-level alignment quality, and scalability, avoiding the domain-specific biases present in datasets like CCAligned [12] or OpenSubtitles [13].

To explore the impact of multilingual exposure, we construct five variants of the training data by varying the proportion of Chinese-to-English examples (zh_ratio ∈ {0.0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0}). This controls for total dataset size and domain while modulating language diversity:

zh_ratio = 0.0: Monolingual Englishzh_ratio = 0.25–0.75: Mixed bilingualzh_ratio = 1.0: Monolingual Chinese

Each sample is selected with the specified probability from the aligned pair. All examples are filtered for language quality, deduplicated, and converted to JSON format compatible with LLaMA-Factory’s pretraining pipeline [14].

Evaluation

We evaluate all models on a suite of tasks probing logical reasoning, fairness, common sense, and multilingual understanding. Our benchmarks include:

- Logical Reasoning: GSM8K [15], MATH [16], HumanEval [17], GPQA Diamond

- Fairness: TruthfulQA [18], AgentHarm [19], TOXIGEN [20]

- Common Sense: HellaSwag [21], SuperGLUE [22], BIG-Bench Hard

- Multilingual Understanding: MMMLU, Belebele [7], MGSM [6]

These tasks were chosen to evaluate both task-specific and general reasoning improvements, as well as the extent to which multilingual exposure reduces bias and improves robustness across domains.

Results

Optimal Split

As shown in Figure 1, we see that the optimal split for performance was using the 0.25 data split. This appears to retain the models initial performance and prevents catastrophic knowledge collapse.

Fig 1. Model performance across different zh_ratio splits

Benchmark Performance

Overall, as shown in Figure 2, all the benchmarks evaluated seem to increase in performance, except for hellaswag. The highest relative gain we see is in humaneval with over 130% performance boost.

Fig 2. Relative performance gains across benchmarks

Detailed Benchmark Specific Performance

To further understand the nuance driving these performance changes, dive into the specific subtasks for each benchmark.

Belebele: As shown in Figure 3, 3/4 of the sub tasks are improved. With the biggest increases seen in languages like Urdu, Southern Pashto, and Lithuanian. The languages that see the largest decrease in performance are Standard Tibetan, Macedonian, and Macedonian. Surprisingly, while the training data was in Chinese, that is not where we see the biggest gain.

Fig 3. Belebele benchmark performance by language

Math: For math, as shown in Figure 4, we see increase in subtopics like geometry, algebra, and probability. On the other hand, performance in prealgebra, number theory, and precalculus diminish in score.

Fig 4. Mathematics performance by subtopic

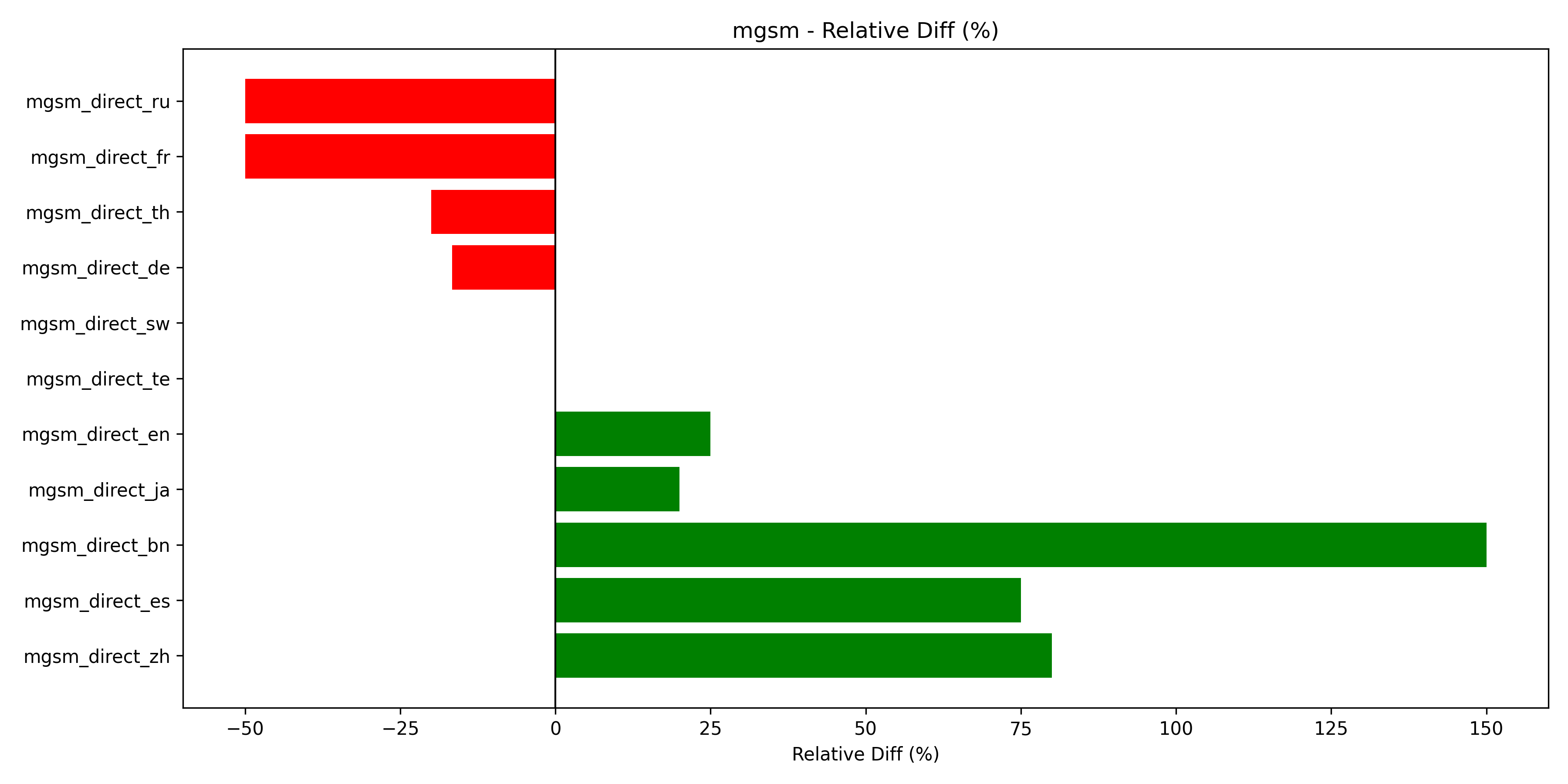

MGSM: MGSM is delineated across languages. As shown in Figure 5, we see big performance gains in Chinese, Spanish, and English. On the contrary, Russian, French, and Thai.

Fig 5. MGSM multilingual math performance

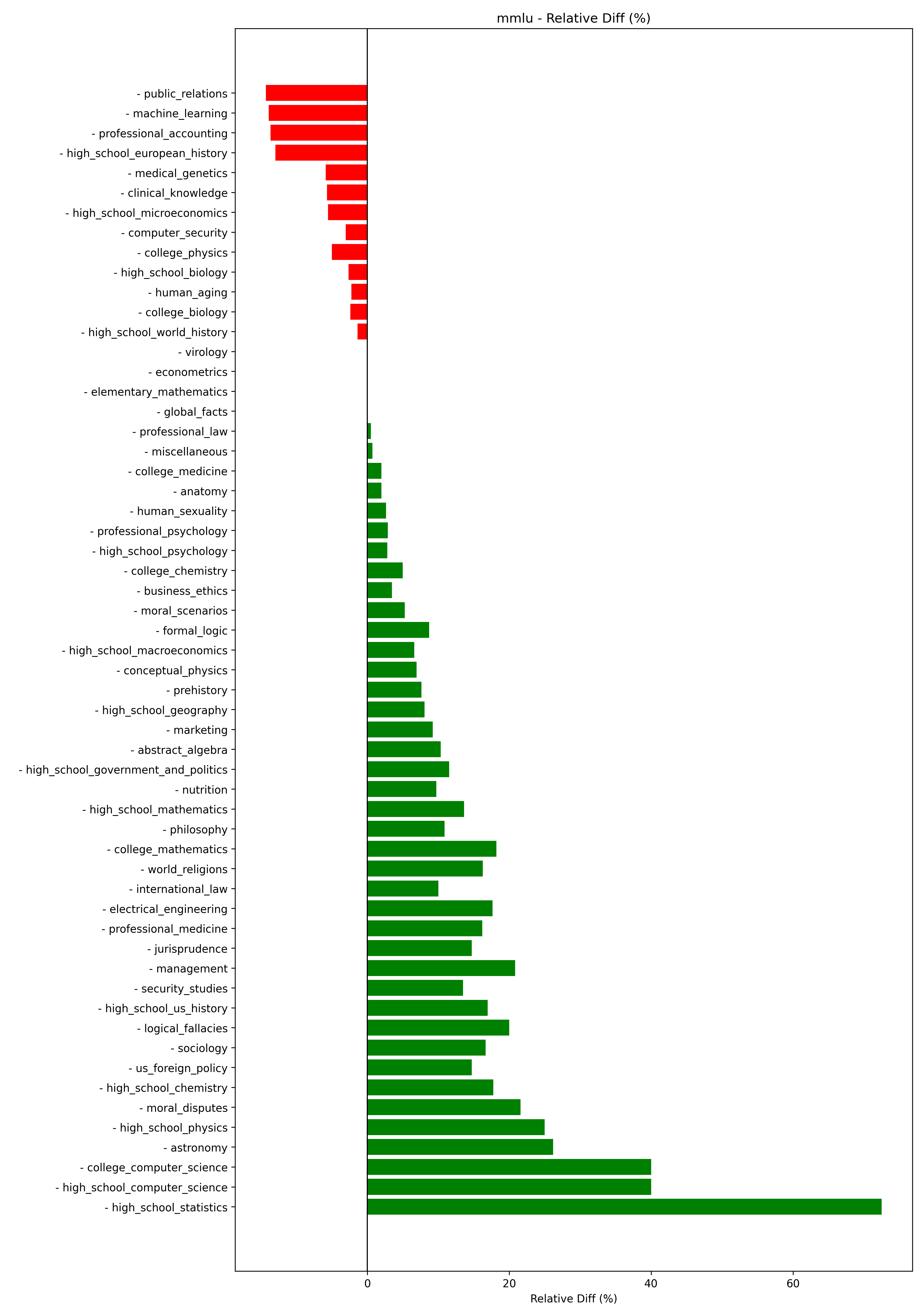

MMLU: As shown in Figure 6, logical topics like statistics, computer science, and astronomy, see big performance gains. However, public relations, machine learning, and accounting see diminishing performance.

Fig 6. MMLU performance across subjects

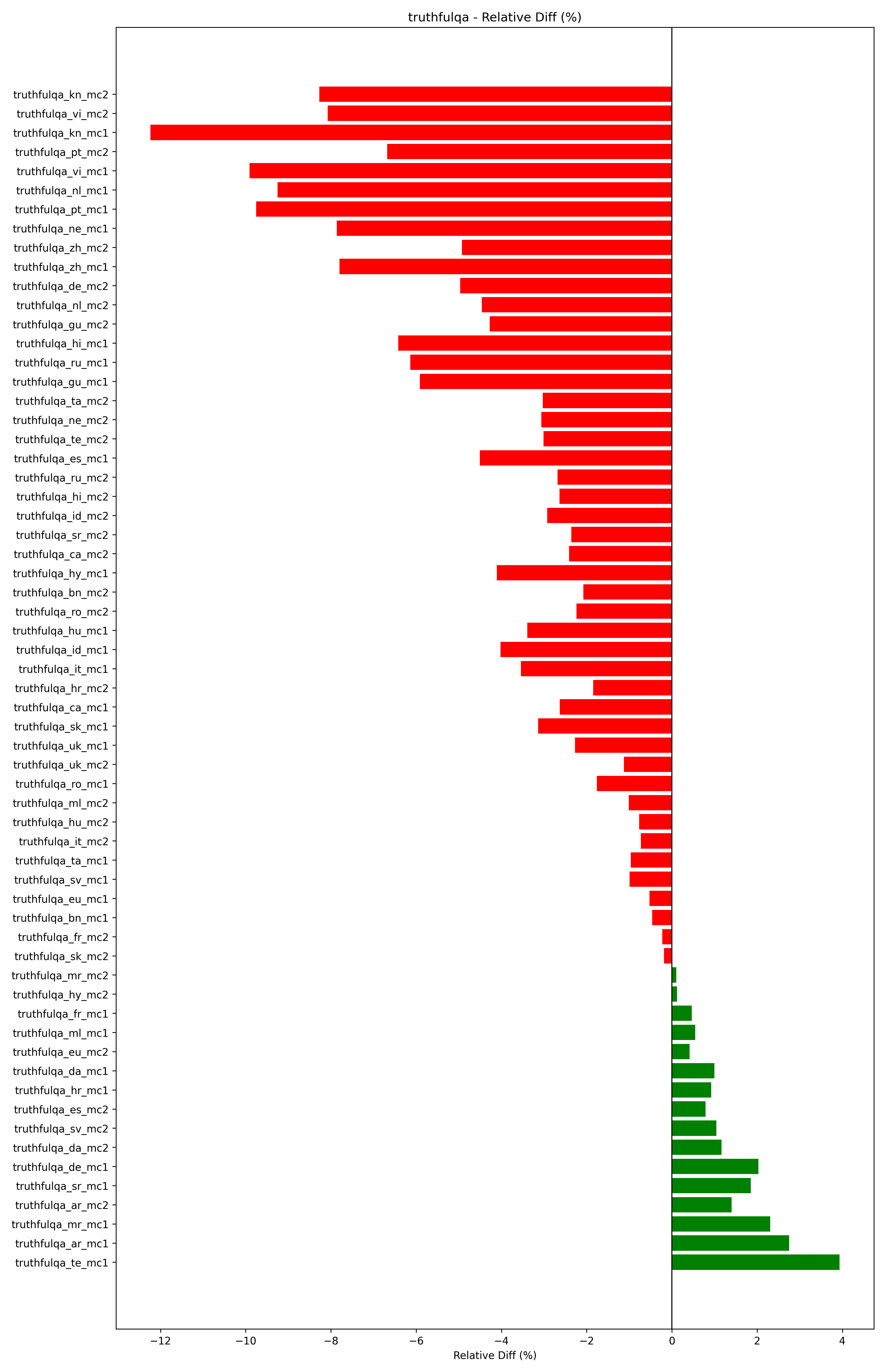

TruthfulQA: As shown in Figure 7, this metric sees the most decrease in performance; with over a third of the scores decreasing. Surprisingly, we see performance decrease even in the language of interest, Chinese.

Fig 7. TruthfulQA performance changes

These nuanced patterns underscore the interplay between linguistic typology and task semantics. Multilingual exposure enhances certain cognitive pathways while occasionally introducing distributional biases that affect domain‑specific tasks.

Conclusion

This study provides the first causal investigation into the cognitive parallels between human multilingualism and multilingual LLM pretraining. Under matched data, compute, and architectural settings, introducing moderate multilingual exposure (25% non‑English data) yields consistent gains in logical reasoning, code synthesis, and cross‑linguistic generalization, validating the cross‑lingual knowledge transfer hypothesis. These enhancements mirror cognitive benefits documented in polyglot human speakers, including flexible abstraction and resistance to knowledge erosion.

However, not all tasks uniformly benefit: declines in fairness benchmarks (TruthfulQA) and specific common‑sense challenges (HellaSwag) highlight potential trade‑offs. Future work should explore adaptive sampling strategies, continual pretraining techniques, and curriculum learning to maximize multilingual gains while mitigating biases. Additionally, extending analysis to larger architectures and more typologically diverse corpora will further clarify the generality of our findings.

By bridging cognitive science theories of multilingualism with empirical LLM evaluation, our work paves the way for designing more robust, fair, and versatile language models that harness the full spectrum of human linguistic diversity.

References

[1] Perlovsky, L. (2009). Language and cognition. Neural Networks, 22(3), 247–257.

[2] DeKeyser, R., & Koeth, J. (2011). Cognitive aptitudes for second language learning. In Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning.

[3] Bialystok, E., & Poarch, G. (2014). Language experience changes language and cognitive ability. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft: ZfE.

[4] Hurst, A., Lerer, A., Goucher, A. P., Perelman, A., Ramesh, A., Clark, A., … Radford, A. (2024). GPT-4o system card. arXiv.

[5] Guo, D., Yang, D., Zhang, H., Song, J., Zhang, R., Xu, R., … Bi, X. (2025). DeepSeek-R1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in LLMs via reinforcement learning. arXiv:2501.12948.

[6] El-Kishky, A., Chaudhary, V., Guzmán, F., & Koehn, P. (2020). CCAligned: A massive collection of cross-lingual web-document pairs. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2020.

[7] Lison, P., & Tiedemann, J. (2016). OpenSubtitles2016: Extracting large parallel corpora from movie and TV subtitles. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2016) (pp. 923–929).

[8] Barrault, L., Bojar, O., Costa-jussà, M. R., Federmann, C., Fishel, M., Graham, Y., … Monz, C. (2019). Findings of the 2019 Conference on Machine Translation (WMT19). ACL.

[9] Schwenk, H., & Douze, M. (2019). WikiMatrix: Mining 135M parallel sentences in 1620 language pairs from Wikipedia. arXiv preprint.

[10] Ziemski, M., Junczys-Dowmunt, M., & Pouliquen, B. (2016). The United Nations Parallel Corpus v1.0. In Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation.

[11] Cobbe, K., Kosaraju, V., Bavarian, M., Chen, M., Jun, H., Kaiser, L., … Nakano, R. (2021). Training verifiers to solve math word problems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.14168.

[12] Hendrycks, D., Burns, C., Kadavath, S., Arora, A., Basart, S., Tang, D., … Steinhardt, J. (2021). Measuring mathematical problem solving with the MATH dataset. arXiv.

[13] Chen, M., Tworek, J., Jun, H., Yuan, Q., de Oliveira Pinto, H., Kaplan, J., … Brockman, G. (2021). Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.03374.

[14] Yang, Z., Zhang, S., Thoppilan, R., … (2023). Measuring massive multitask language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.16863.

[15] Lin, S., Hilton, J., & Evans, O. (2021). TruthfulQA: Measuring how models mimic human falsehoods. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.07958.

[16] Li, X., Xu, W., Zhang, Z., McGuffie, K., Gao, T., Henderson, P., … Chang, K.-W. (2023). AgentHarm: Evaluating harmfulness of conversational agents. arXiv preprint.

[17] Hartvigsen, T., Goel, S., Röttger, P., Glaese, A., & Rae, J. (2022). ToxiGen: A large-scale machine-generated dataset for adversarial and implicit hate speech detection. In ACL 2022.

[18] Zellers, R., Holtzman, A., Bisk, Y., Farhadi, A., & Choi, Y. (2019). HellaSwag: Can a machine really finish your sentence? In ACL 2019.

[19] Wang, A., Pruksachatkun, Y., Nangia, N., Singh, A., Michael, J., Hill, F., … Bowman, S. R. (2019). SuperGLUE: A stickier benchmark for general-purpose language understanding systems. In Proceedings of NeurIPS 2019.

[20] Bandarkar, L., Liang, D., Muller, B., Artetxe, M., Shukla, S. N., Husa, D., … Khabsa, M. (2024). Belebele benchmark: Parallel reading comprehension dataset in 122 language variants. ACL. URL: https://aclanthology.org/2024.acl-long.44

[21] Shi, F., Suzgun, M., Freitag, M., Wang, X., Srivats, S., Vosoughi, S., … Wei, J. (2022). Language models are multilingual chain-of-thought reasoners. arXiv preprint. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.03057

[22] ParaCrawl Project. (2024). ParaCrawl English–Chinese v1.0. Retrieved from https://web-language-models.s3.amazonaws.com/paracrawl/bonus/en-zh-v1.txt.gz

[23] Liu, B., Liu, X., & Ji, H. (2020). ParaMed: A parallel corpus of medical research articles for Chinese-English translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.09133. URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.09133

[24] Zhang, J., Xue, B., Liu, S., & Zhou, G. (2024). Web-crawled corpora for English–Chinese neural machine translation: A systematic comparison. Electronics, 13(7), 1381. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13071381

[25] Wu, J., Wei, J., & Duan, W. (2021). A bilingual Chinese-English parallel corpus of financial news articles. Journal of Open Humanities Data, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.5334/johd.62

[26] Zheng, Y., Zhang, R., Zhang, J., Ye, Y., Luo, Z., Feng, Z., & Ma, Y. (2024). LlamaFactory: Unified efficient fine-tuning of 100+ language models. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 3: System Demonstrations) (pp. 400–410). https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/2024.acl-demos.38