Weak Supervision with Heterogeneous Annotations

Fully-supervised Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have become the state-of-the-art for semantic segmentation. However, obtaining pixel-wise annotations is prohibitively expensive. Thus, weak supervision has become popular to reduce annotation costs. Although there has been extensive research in weak supervision for semantic segmentation, prior methods have focused solely on a single type of weak annotation (e.g. points, scribbles, bounding boxes, image tags), otherwise known as homogeneous annotations. This results in rigidity, often forcing researchers to either use a combination of multiple algorithms or throw out valuable weak labels of a different type. Universal weak supervision methods attempt to remedy this by being compatible with several types of weak labels. Despite this, there has been little to no study on the effects of heterogeneous annotations when using universal weak supervision methods. In this work, we use the state-of-the-art universal weak supervision method, Universal Weakly Supervised Segmentation by Pixel-to-Segment Contrastive Learning (SPML), to study the effects of heterogenous annotations. We show extensive results for several types of heterogeneous annotations and compare these results with their homogeneous counterparts. In addition to this, we explore how information in the language domain can significantly improve weak annotation results while requiring no further cost in annotations.

Introduction

With the recent advances of deep learning, groundbreaking results have been achieved in the field of computer vision. Despite this, training deep learning models require large amounts of data that must be meticulously annotated by human workers. Not only is this tedious for such workers, manual annotations are time-consuming and expensive. This is further exacerbated for the semantic segmentation, which required pixel-wise annotation. To reduce this annotation cost, we employ universal weak supervision and use the state-of-the-art method SPML [1]. More specifically, we study the effects of heterogeneous weak labels as a means of maximizing the flexibility and efficiency of weak supervision. In addition to this, we develop two novel modifications that significantly improve the segmentation results produced by SPML. Both these modifications augment the vision problem using information in the language domain. We applied our approach to the PASCAL VOC2012.

Overall, our contributions are as follows:

- We study the effects of heterogeneous labels when using universal weak supervision methods. In particular, we study two different types of heterogenous labels: mixed labels (where each point of data has one weak label but the dataset is comprised of different types of weak labels) and combined labels (where each point of data is a union of two or more different types of weak labels).

- We incorporate a novel word similarity loss which utilizes class names as a form of weak supervision.

- We use the state-of-the-art language-image model, Contrastive Language-Image Pre-Training (CLIP) [2], and take advantage of its zero-shot capabilities as a novel post-processing method, further improving the results of SPML.

Note that contributions 2 and 3 improve our segmentation results while requiring no additional annotations.

For the rest of our report, we will now go over related work, methodology, and experimental results. We conclude the report with a brief discussion concerning future research directions.

Related Work

There have been several papers in weak supervision for semantic segmentation. Previous work has utilized an oversegmentation and labeled unlabed segments based on similarity to labeled segments. In [3], labels are generated based on alternating optimization of network predictions and groundtruth proposals, incorporating similarity of low-level image features for different segments. In [1], the researchers incorporate more relationships between segments - including semantic cocurrence and feature affinity - and optimize a constrative learning framework.

Rather than labeling segments, other work has focused on labeling pixels. In [4], the researchers utilize a DenseCRF loss to optimize pixel-level groundtruth proposals based on low-level image features. They use an alternating optimization framework to optimize network parameters and groundtruth proposals. In [5], pseudo semantic-aware seeds are generated, which are formed into semantic graphs. The graphs are passed to an affinity attention layer designed to acquire the short- and long- distance information from soft graph edges to accurately propagate semantic labels from the confident seeds to the unlabeled pixels. In [6], image pixels are represented as a graph with edge weights corresponding to low-level and high-level image features. An affinity matrix is generated from its minimum spanning tree which is used to assign labels to unlabeled pixels

There are only two works ([1] and [5]), which can use image tags, bounding boxes, scribbles, and point annotations for weak supervision. However, no prior work has explicitly focused on heterogeneous annotations and, additionally, also incorporated information from the language domain to improve segmentation performance.

Methodology

In this section, we formulate our proposed methods. First, we will briefly go over the SPML algorithm, which we use as a base model. Next, we formulate our novel word embedding loss and its incorporation into the baseline algorithm. Finally, we detail the CLIP post-processing step. For a more detailed description of the SPML algorithm, please refer to the original paper [1].

SPML

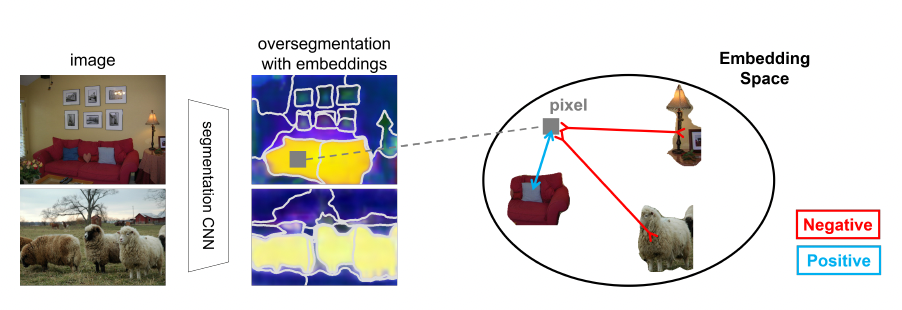

The SPML models generates pixel-wise embeddings from a semantic segmentation CNN with contrastive learning between pixels and segments. It utilizes 3 types of contrastive relationships between pixels and segments in the feature space, capturing low-level image similarity, semantic annotation, and semantic co-occurrence. An overview of how the pixel embeddings are generated from the segments can be seen below.

The pipeline for the model is as follow. For each batch of input images, spherical K-means clustering is performed on the segmentation CNN embeddings (output of second to last layer) and pixel coordinates to oversegment each image in the batch. For each pixel in the batch of images, contrastive learning relationships are applied to label segments as positive or negative.

For low-level similarity loss, the pixel’s image segment is labeled positive and other segments are labeled as negative. For semantic annotation loss, all batch segments with the pixel’s label (except the pixel’s own) are labeled as positive and segments without the pixel’s label are labeled as negative (unlabeled segments are ignored). For the semantic co-currence loss, if any images in the batch share any semantic labels with the pixel’s image, then all the batch segments in the pixel’s image and those images are labeled as positive and all other segments are labeled as negative. The loss function for the model is

\[L(i) = \lambda_I L_{SegSort+}(i, V^{+}, V^{-}) + \lambda_C L_{SegSort+}(i, C^{+}, C^{-}) + \lambda_O L_{SegSort+}(i, O^{+}, O^{-})\]Word Embedding Loss

We devise a novel word embedding similarity. For each image in the batch, we generate word embeddings for all the provided semantic image tags using a pretrained BERT model. For each image tag, we find the most similar tag by applying apply cosine similarity to the word embeddings.

For each pixel in the image, all batch segments with the pixel’s label and the most similar label are labeled positive and segments with different labels are labeled as negative. Thus the new loss function is

\[L(i) = \lambda_I L_{SegSort+}(i, V^{+}, V^{-}) + \lambda_C L_{SegSort+}(i, C^{+}, C^{-}) + \lambda_O L_{SegSort+}(i, O^{+}, O^{-}) + \lambda_{W} L_{SegSort+}(i, W^{+}, W^{-})\]Inference and CLIP Post-processing

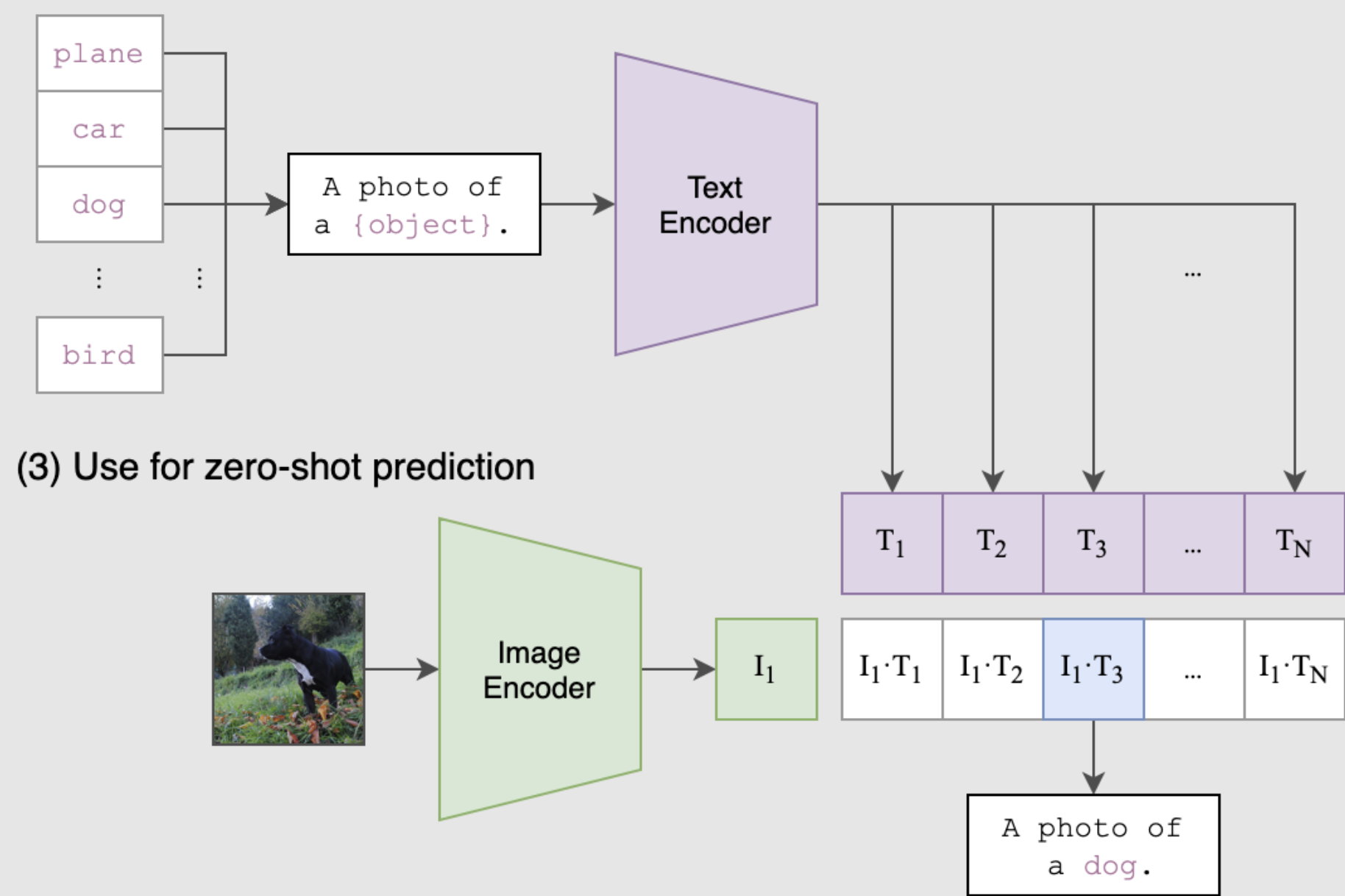

For inference, we generate segments on both the training set and inference set. We predict labels on the inference segments based on KNN on the labeled training segments. Additionally, we use CLIP to influence the vectors for KNN by penalizing segmentations for classes that are unlikely to appear in the image.

CLIP is a neural network trained on image-text pair and is valuable in the weak supervision setting because additional annotations are unneeded. As shown below, CLIP takes in as input an image along with text describing the contents of the image. The model outputs a prediction of whether or not the sentence is true.

We provide a sentence for each possible class to get softmax probabilities for the image using the CLIP model. We adjust the feature affinities based on the CLIP probability that the tag is in image.

Let us denote the feature embeddings obtained from the inference set as \(I \in R^{n \times c}\) where \(n\) is the size of the inference set and \(c\) is the embedding dimension. Let us also denote \(T \in R^{m \times c}\) as the feature embeddings obtained from the original training set, where \(m\) is the size of the training set and \(c\) is defined as before. We can then obtain the feature affinity matrix by \(F = I T^T\).

Next, let us denote \(t \in R^m\) as the generated training set labels and \(p^{CLIP} \in R^{20}\) as the softmax probabilities provided by CLIP for the 20 classes in PASCAL VOC2012 for an arbitrary image. We can then compute our adjusted feature affinities by

\[F_{ij}^* = F_{ij} + \alpha 1 [t_j = k] p_k^{CLIP} \ \forall \ i \in [n], \forall \ j \in [m], \forall \ k \in [20]\]where \(1[.]\) is the indicator function and \(\alpha\) is a user-defined scaling factor. For our experiments, we found \(\alpha = 0.005\) to provide good performance. With this augmented feature affinity matrix, we then perform KNN as before.

Results

We obtain results for two types of heterogeneous weak annotations - mixed labels and combined labels - and homogenous weak annotations for comparison. All our models were trained with a batch size of 4, and for a total of 30000 iterations. Images from the PASCAL VOC2012 dataset were downsized by 50% for memory purposes. For training, we used a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti.

Mixed Labels

For mixed labels, we perform the following experiments:

- 50% of training images with scribbles and 50% of training images with bounding boxes

- 50% of training images with scribbles and 50% of training images with image tags

- 50% of training images with bounding boxes and 50% of training images with image tags

Combined Labels

For combined labels, we perform the following experiments:

- each training image has one scribble and one bounding box

- each training image has one scribble and semantic class names

Analysis

Experimental Results

Below, we showcase the results for each type of annotation. Homogeneous results are shown for image tags, bounding boxes, and scribbles to serve as a baseline (BL). To quantify accuracy, we use multi-class intersection over union (mIoU), a common metric for evaluating multi-class image segmentation.

| Annotation | Validation mIoU (%) |

|---|---|

| Tags (BL) | 64.22 |

| BBox (BL) | 65.77 |

| Scribbles (BL) | 67.89 |

| 50% Scribbles + 50% Bbox | 66.89 |

| 50% BBox + 50% Tags | 64.95 |

| 50% Scribbles + 50% Tags | 64.65 |

| Scribbles + BBox | 68.48 |

| Scribbles + CLIP | 68.38 |

| Scribbles + WE | 68.47 |

| Scribbles + CLIP + WE | 69.11 |

From the baseline results, we observe that scribbles perform the best and bounding boxes and image tags performing worse in that order. The poor performance of image tags match our expectation because they require the least annotation effort. Our mixed label annotations perform comparably to their homogeneous counterparts. As expected, each models trained on mixed labels are in the range of the models’ performances trained on each of the homogeneous labels that they consist of.

Our combined label consisting of scribbles and bounding boxes exceeds the performance of all homogeneous and mixed labels. This makes sense intuitively because combining weak labels results in higher quality annotation for network supervision.

Finally, we observe that our word embedding loss and CLIP post-processing both improve the performance of homogeneous scribbles. In fact, the performances for each modification are roughly equivalent to the performance of the models trained on combined scribbles and bounding boxes. We note that the best performance is achieved when combining both the word embedding loss and CLIP post-processing procedure. This shows that the benefits of each language-domain modification may compound and may provide a more cost-effective performance boost than other annotation types.

Below, we show two examples of our language-domain modifications to SPML’s segmentation. Notice that for each example, the segmentation produced by homogeneous scribbles contain classes that do not belong to ground truth. When including the word embedding loss, we see a clear improvement for the example in the first row while the example in the second row completely removes the incorrect class prediction. Adding the CLIP post-processing completely remedies the incorrect class prediction in the first example while for the second example, the motorcycle rear-view mirror is better segmented. Overall, we observe excellent improvements when incorporating language-domain information to the vision task. Again, these results are exciting because there is virtually no additional annotation cost.

Error Analysis

Next, we perform an error analysis for our top performing methods (as well as related approaches) by observing the class accuracies as shown below. Each row constitutes the segmentation accuracies (%) for a specific class with the last row being the mIoU (%) for the overall method. The highest metric for each class is bolded. As shown below, we can see that there is a relatively even distribution in the best performance by classes for the shown methods.

We notice that the vast majority of these classes contain accuracies that are relatively similar to eachother (within +/- 2%). When comparing SC+BBox to homogeneous scribbles and bounding boxes, we notice that there is an overall improvement for most classes. For example, model performance on Boat, Bus, Dining Table, and Motor Bike is better in the combined setting. Additionally, certain classes that perform poorly for either label type tend to not perform as poorly in the combined seting (e.g. Chair).

By far the largest differentials are produced by our best method, SC+WE+CLIP, when compared to the homogeneous scribbles baseline for the classes horse, sheep, and cow. These classes possess an accuracy improvement of approximately 5%, 9%, and 11%, respectively. Interestingly, all these classes are animals. As many animals possess similar qualities (e.g. quadrupedal, tails, etc.), we suspect that distinguishing these classes purely from visual differences may be challenging. In addition to this, all these animals are farm animals and therefore, most likely to possess similar backgrounds, eliminating any contextual help for the model. Here, an explicit confirmation of the animal through language-domain information clearly helps the segmenter. We also notice that SC+WE outperforms SC on these classes as well but does not have as high of performance as SC+WE+CLIP, reinforcing the notion that the benefits of our language-domain modifications may compound.

| Class | BBoxes (BB) | Scribbles (SC) | SC+BB | SC+WE | SC+WE+CLIP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background | 91.06 | 91.54 | 91.76 | 91.71 | 91.45 |

| Aeroplane | 76.24 | 79.35 | 75.36 | 78.99 | 76.41 |

| Bike | 35.30 | 34.73 | 35.12 | 33.84 | 33.38 |

| Bird | 81.55 | 80.63 | 80.83 | 78.95 | 77.44 |

| Boat | 61.57 | 63.47 | 66.17 | 60.54 | 60.00 |

| Bottle | 63.96 | 71.12 | 72.52 | 72.99 | 72.31 |

| Bus | 83.25 | 86.94 | 87.08 | 86.84 | 86.75 |

| Car | 80.38 | 83.38 | 82.00 | 81.31 | 81.12 |

| Cat | 82.23 | 83.72 | 83.98 | 85.81 | 85.44 |

| Chair | 25.56 | 32.19 | 29.74 | 30.61 | 30.54 |

| Cow | 58.99 | 61.53 | 65.56 | 66.94 | 72.50 |

| Dining Table | 53.90 | 47.92 | 55.18 | 52.35 | 54.98 |

| Dog | 76.19 | 79.42 | 79.05 | 80.63 | 80.33 |

| Horse | 65.96 | 66.31 | 66.17 | 69.08 | 71.27 |

| Motorbike | 71.82 | 74.86 | 76.11 | 75.96 | 75.71 |

| Person | 75.78 | 78.81 | 77.89 | 79.19 | 79.19 |

| Plant | 51.37 | 54.00 | 52.29 | 52.92 | 53.09 |

| Sheep | 66.73 | 65.27 | 70.61 | 71.11 | 74.12 |

| Sofa | 39.00 | 43.01 | 41.88 | 43.99 | 45.27 |

| Train | 73.73 | 78.31 | 78.06 | 79.63 | 79.63 |

| Television | 65.80 | 69.77 | 70.77 | 69.69 | 70.47 |

| mIOU | 65.77 | 67.89 | 68.48 | 68.47 | 69.11 |

Conclusion

In this project, we studied the effects of heterogeneous weak labels in the form of mixed and combined labels using the SPML model. We show that mixed labels produce comparable results with their homogenous counterparts while combined labels had improved performance. In addition to this, we developed two novel modifications to the SPML algorithm that incorporate language-domain information in the form of a word embedding loss and CLIP post-processing procedure. We show that both methods individually improved the performance for homogeneous scribbles and when combined, compounded these benefits for further performance boost. In future work, we hope to explore more significant differences in architectures (especially those used by A2GNN) to see if we can extrapolate better performance. Additionally, we hope to utilize active learning to suggest annotation types that may be beneficial to model performance, thus further reducing annotation costs.

References

[1] Ke, Tsung-Wei, Jyh-Jing, Hwang, and Stella X., Yu. “Universal Weakly Supervised Segmentation by Pixel-to-Segment Contrastive Learning”, arXiv, 2021.

[2] Radford, Alec, Jong Wook, Kim, Chris, Hallacy, Aditya, Ramesh, Gabriel, Goh, Sandhini, Agarwal, Girish, Sastry, Amanda, Askell, Pamela, Mishkin, Jack, Clark, Gretchen, Krueger, and Ilya, Sutskever. “Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision”, arXiV, 2021.

[3] Lin, Di, et al. “Scribblesup: Scribble-supervised convolutional networks for semantic segmentation.” Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2016.

[4] Tang, Meng, et al. “On regularized losses for weakly-supervised cnn segmentation.” Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision. 2018.

[5] Zhang, Bingfeng, et al. “Affinity attention graph neural network for weakly supervised semantic segmentation.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2021).

[6] Liang, Zhiyuan, et al. “Tree Energy Loss: Towards Sparsely Annotated Semantic Segmentation.” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2022).