Character Generation - StyleGAN for Pokémon

Character design is a challenging process: artists need to create a new set of characters tailored to the specific game or animated feature requirements while still following the basic anatomy and perspective rules. In this project, we try to utilize automation to ease the creation process. We add discriminator branches to StyleGAN and incorporate the idea of SemanticGAN to make the character generation process more human controllable.

Motivation

To create a new and unique character for games, anime, etc. it takes years of art training to master drawing skills and digital art software for virtualizing the design ideas. Even acquiring these skills, the process of designing a character takes days, even months, to refine and finalize the design. If we can employ automation, we can ease the creation process. For example, some research uses a neural network based model to do automatic coloring for sketches or line art. If we provide masks such as segmentation maps, some models can generate the illustration. Models like GAN can generate characters’ pictures to have a starting point for designing a character or even characters that can be directly put into practice.

The challenge is when people are trying to design a new character for new work, it is a new concept of art. There are only few data to reference. We are wondering if we can still utilize automation to help with the character design. For example, Pokemon series tends to have a unified color for a Pokemon due to the type system. Also, the line art of Pokemon is cleaner compared to Digimon. To design a new Pokemon, there are only 905 existed Pokemon for us to train. We want to investigate if we can distill knowledge from all similar designs and apply them to new concept arts.

Related Work

Line Art Recognition

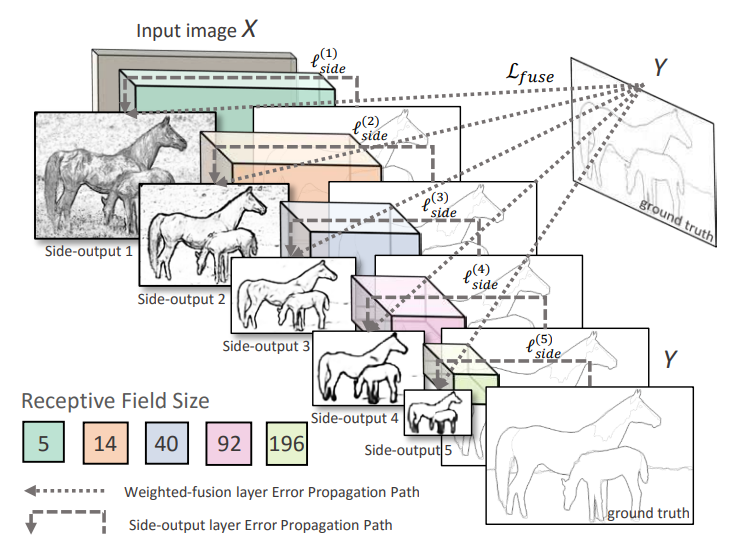

HED [1] utilizes a new edge detection algorithm. It generates line art by image-to-image prediction with a deep learning model. The structure of HED is shown in Fig 1. The input image will go through several convolutional layers. For each convolutional layer, HED has a side-output layer along with deep supervision to guide the side outputs towards edge predictions with the characteristics we want. Therefore, The outputs of HED are multi-scale and multi-level.

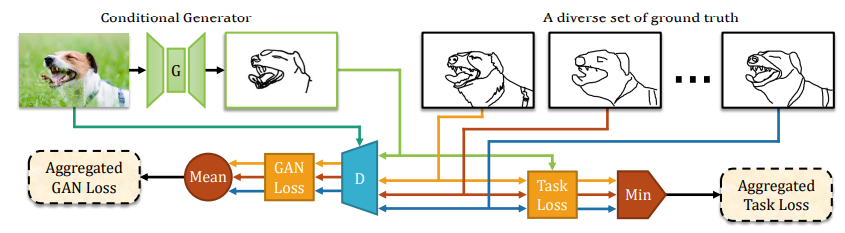

Other than HED, PhotoSketch [3] is another model for people to extract sketch of images. This model is released in 2019 and also gained a lot of attention. HED cannot capture the edge well when the colors of items are close in the image. PhotoSketch uses conditional GAN to predict the most salient contours in images and reflects imperfections in ground truth human drawing, which is different from traditional edge detection algorithms. As shown in Fig 2, PhotoSketch is trained on a diverse set of image-contour pairs that generate conflicting gradients. The discriminator will average the GAN loss across all image-contour pairs, while the regression-loss finds the minimum-cost contour to pair with the train image.

Sketch to Image

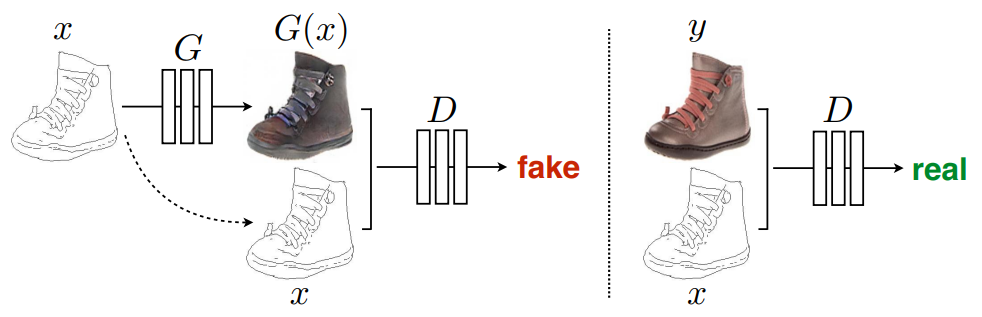

Isola et al. [5] propose Pix2Pix to transform a sketch into an image. Pix2Pix is an example of image-to-image translation. It uses a conditional generative adversarial network (cGAN) to learn the mapping between edge and photo. The idea is shown in Fig 3. The discriminator, D, learns to distinguish between fake (synthesized by the generator) and real {edge, photo} tuples. The generator, G, learns to trick the discriminator. The problem with this model is that it requires a sketch image as input. If we want to have a mass generation such as 1000 characters, we have to provide 1000 sketches. Our proposed model makes the input sketch optional. We allow the mass generation without the user input.

Image Generation

Due to the success of StyleGAN [3] and StyleGAN2 [4] on the photo and anime-style art generation, we are going to focus on the extension and analysis of StyleGAN in this process. In this section, we introduce what is StyleGAN and the direction discovery that can be performed on StyleGAN.

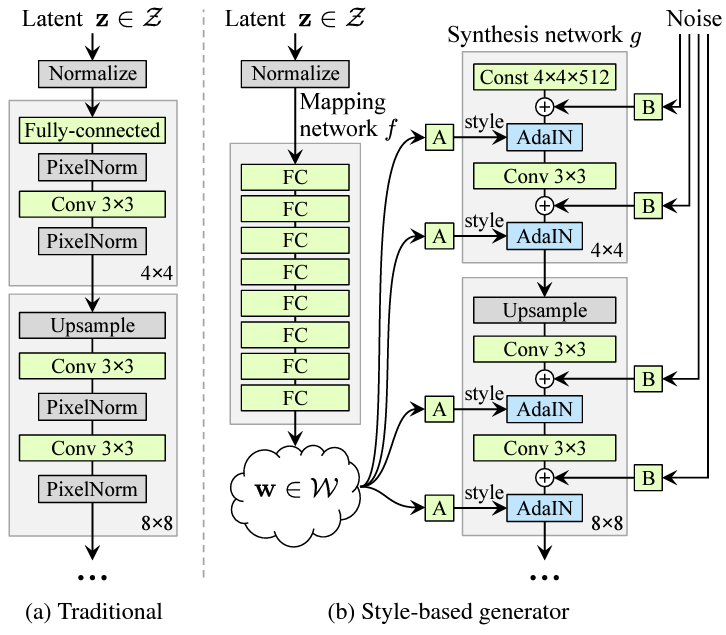

Unlike the traditional GAN where the generator takes a random latent input \(z\), StyleGAN generator takes a constant input of size 4x4x512, and its latent input \(z\) is only used to generate the styles. Specifically, \(z\) is mapped to an intermediate late space \(\mathcal{W}\), whose vector \(w\) will be affine transformed into style \(y\). We can see in Fig 4 that these feature map-specific styles are used to modulate adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN) operations.

Another type of input for StyleGAN generator is the noise image injected into each layer of the network (module B in StyleGAN). These noises are introduced to generate stochastic scale-specific details (i.e. hair and freckles) into the image generation.

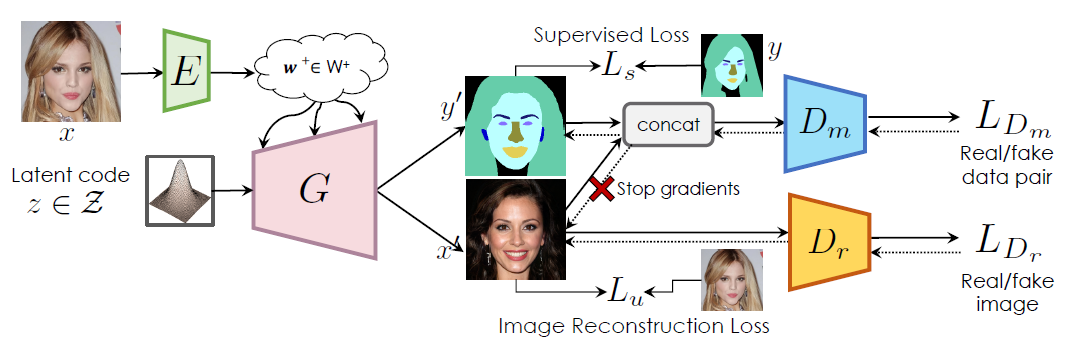

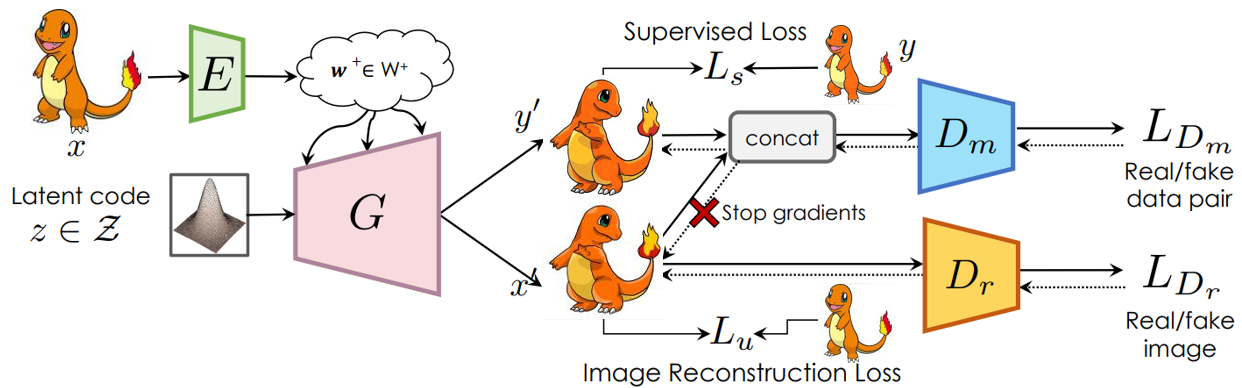

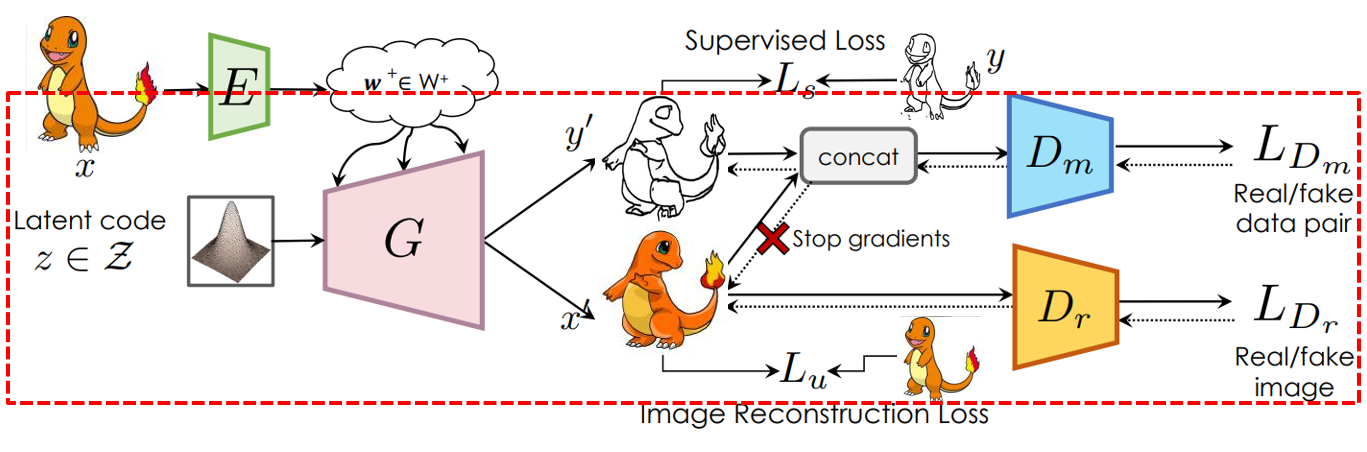

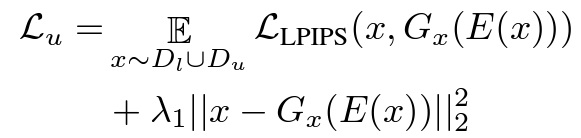

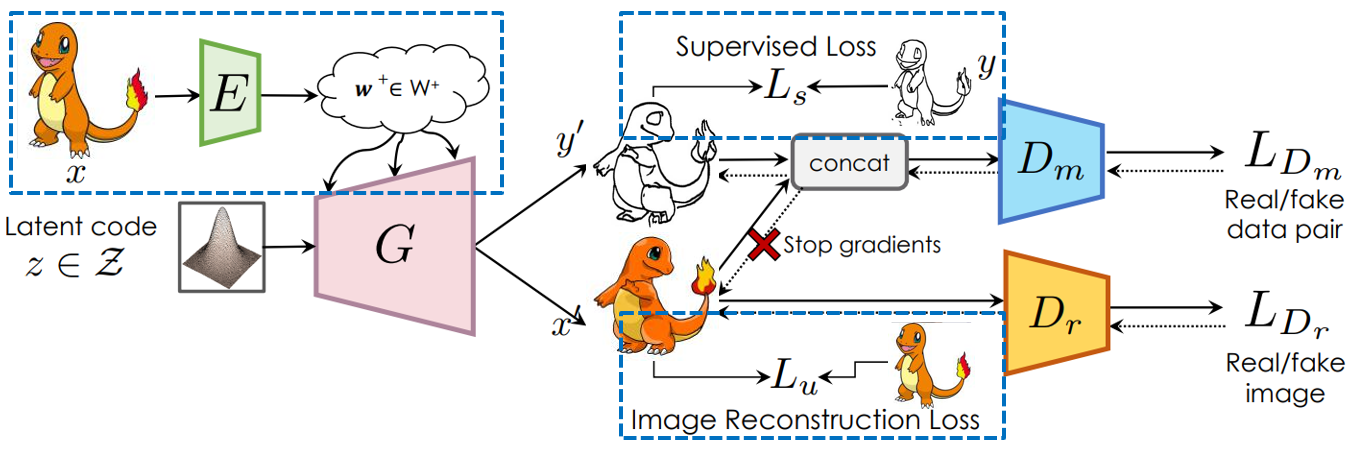

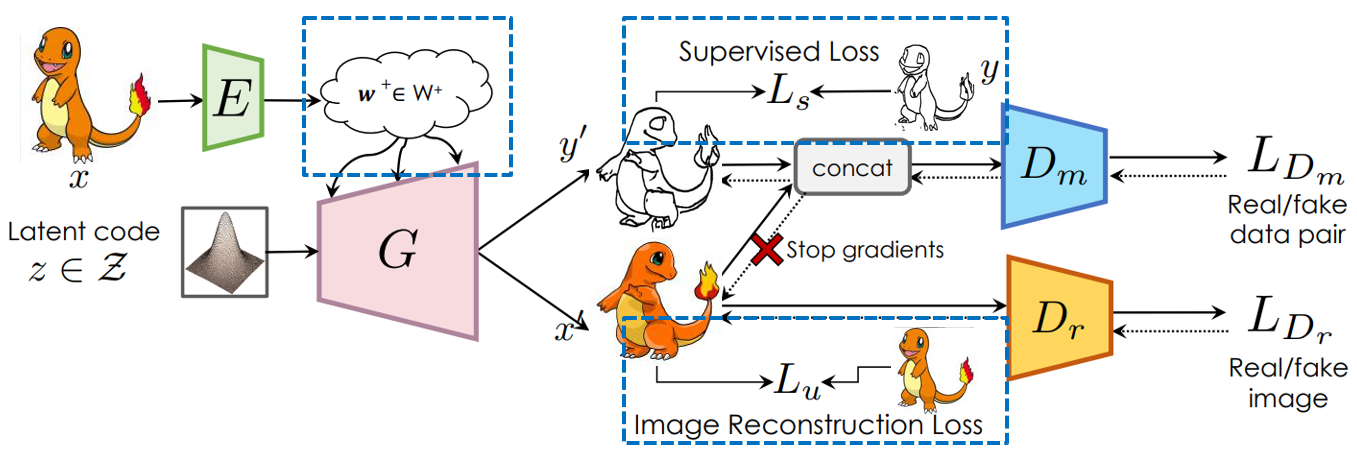

In the practical application of StyleGAN, people usually have insufficient labeled data to train the model. To obtain a better generation ability for StyleGAN, Li et al. [6] propose a novel framework for discriminative pixel-level tasks built on top of styleGAN2, which is called SemanticGAN. It adds a label synthesis branch that generates image labels during the test time. The encoder added is to help with mapping the user inputs to the latent space. It is trained with the supervised loss and the image reconstruction loss as shown in Fig 5. This model is an example of semi-supervised learning. Our model is based on this structure.

Contributions

- Curate a clean collection of Pokemon image data from 8 generations on Kaggle and include available generation 9 and Arceus Pokemon images in the dataset.

- Generate line art and color maps as labels.

- Extend the existing StyleGAN model with more discriminator branches of different prediction tasks.

- Allow humans to decide whether they want to provide the sketch to generate the new Pokemon.

Implementation

Data

| Dataset | Image Number | Link |

|---|---|---|

| Veekun Sprites 256x256 | 819 | kaggle link |

| Images without label | 7357 | kaggle link |

| Online Images | 324 | Pokemon Database |

We combined the images from different datasets found on Kaggle. Most of the pictures in the dataset are Pokemon from generations 1 to 6. Therefore, we self-collected images of Pokmon from generation 7 to 9 and Pokemon from Arceus to increase the size of input images. We unify the size and the format of Pokemon images from different datasets. The images are resized according to the width and height ratio, and then we add padding to make each image 256x256 pixels.

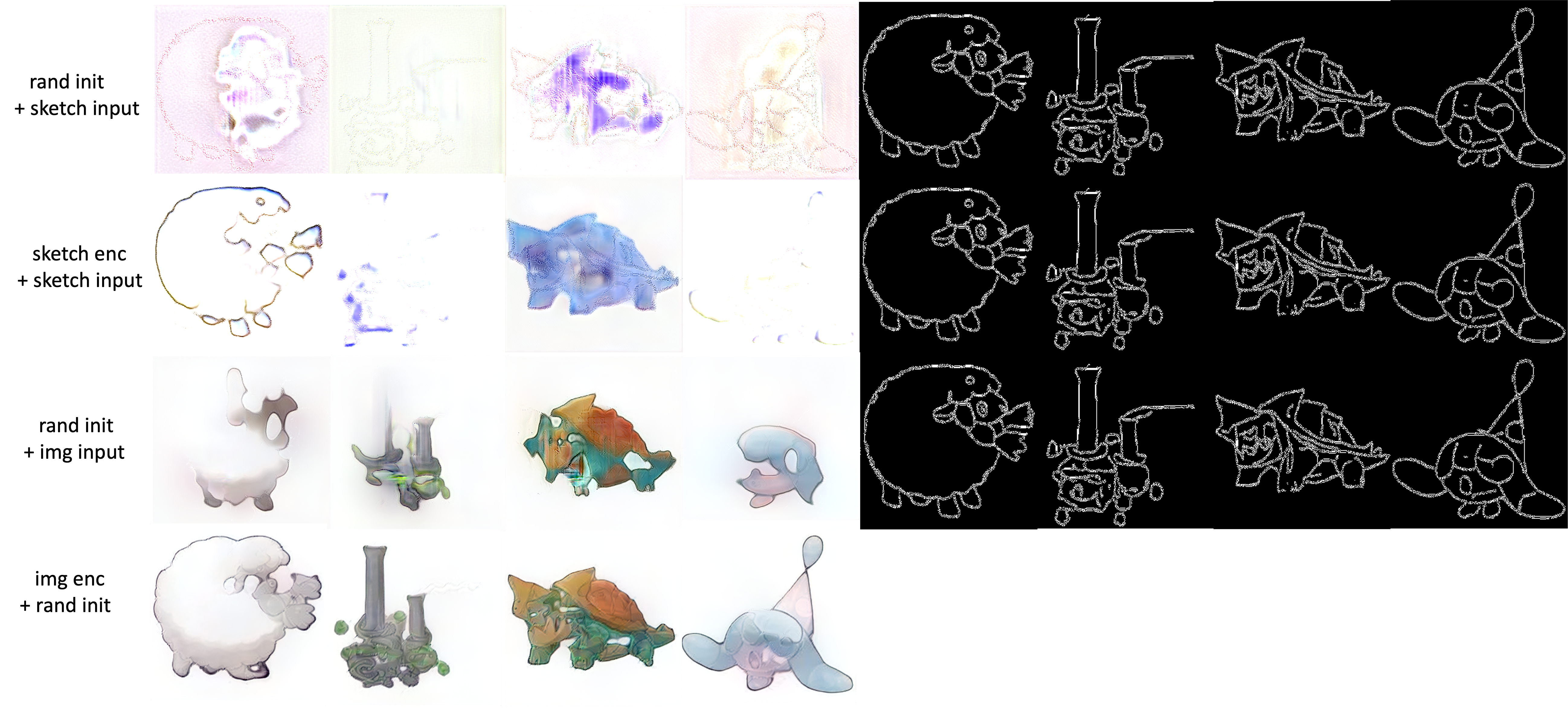

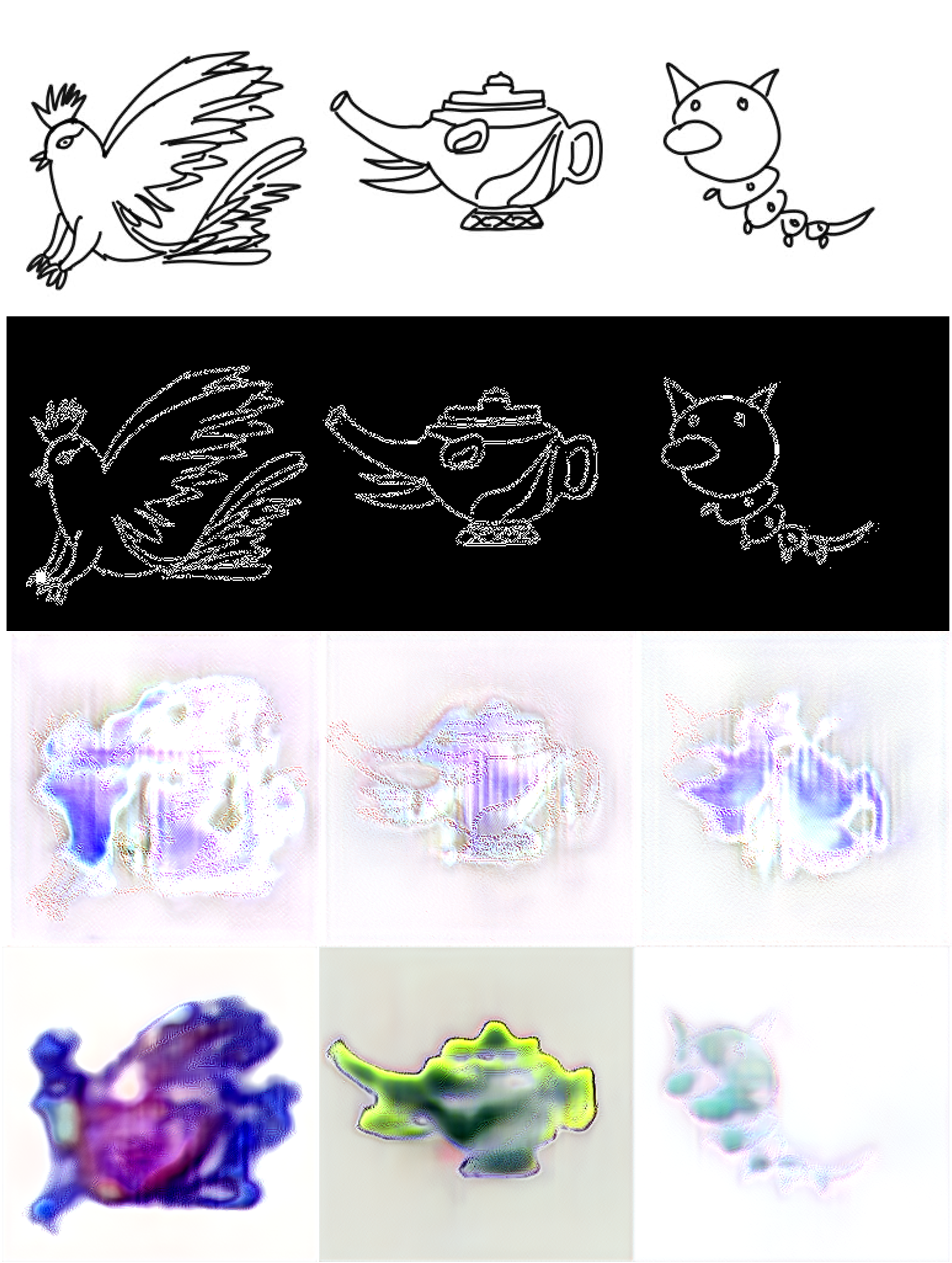

Sketch

We apply HED and PhotoSketch to extract the line art of the images to be the labels. The results are shown in Fig 6. The first row is the original image. The second row is the sketch generated by HED, and the last row is the sketch rendered by PhotoSketch. Unlike HED, PhotoSketch’s result is more like human-drawing line art. Since not most people have well-trained art skills. Given a limited time, it is common for people, especially us, to draw the line art in PhotoSketch’s style. Therefore, we choose to use the PhotoSketch’s sketch as labels, the input to the branch.

Color Maps

In the proposal, we were thinking of generating semantic maps as labels. However, Pokemon have different kinds of forms. The design of Pokemon is based on items, animals, or humans. It is hard for us to define the body, hand, or foot of Pokemon, not even the eyes, nose, or mouth. Thus, we decide to generate color maps as a substitution. Our idea is to choose several colors as the base color and transform the original image into the image consisting of the chosen colors. At the same time, we believe this idea is able to extend to the application that the user can use the color map to decide the color of the final generated Pokemon. Therefore, we want to choose the color commonly used in drawing. We found the list of the colors that Crayola Crayon Colors. Jenny has organized the color list of 64 Crayola Crayon Colors in 2017 [7] and 73 Crayola Crayon Colors in 2020 [8]. We decide to experiment with these two lists.

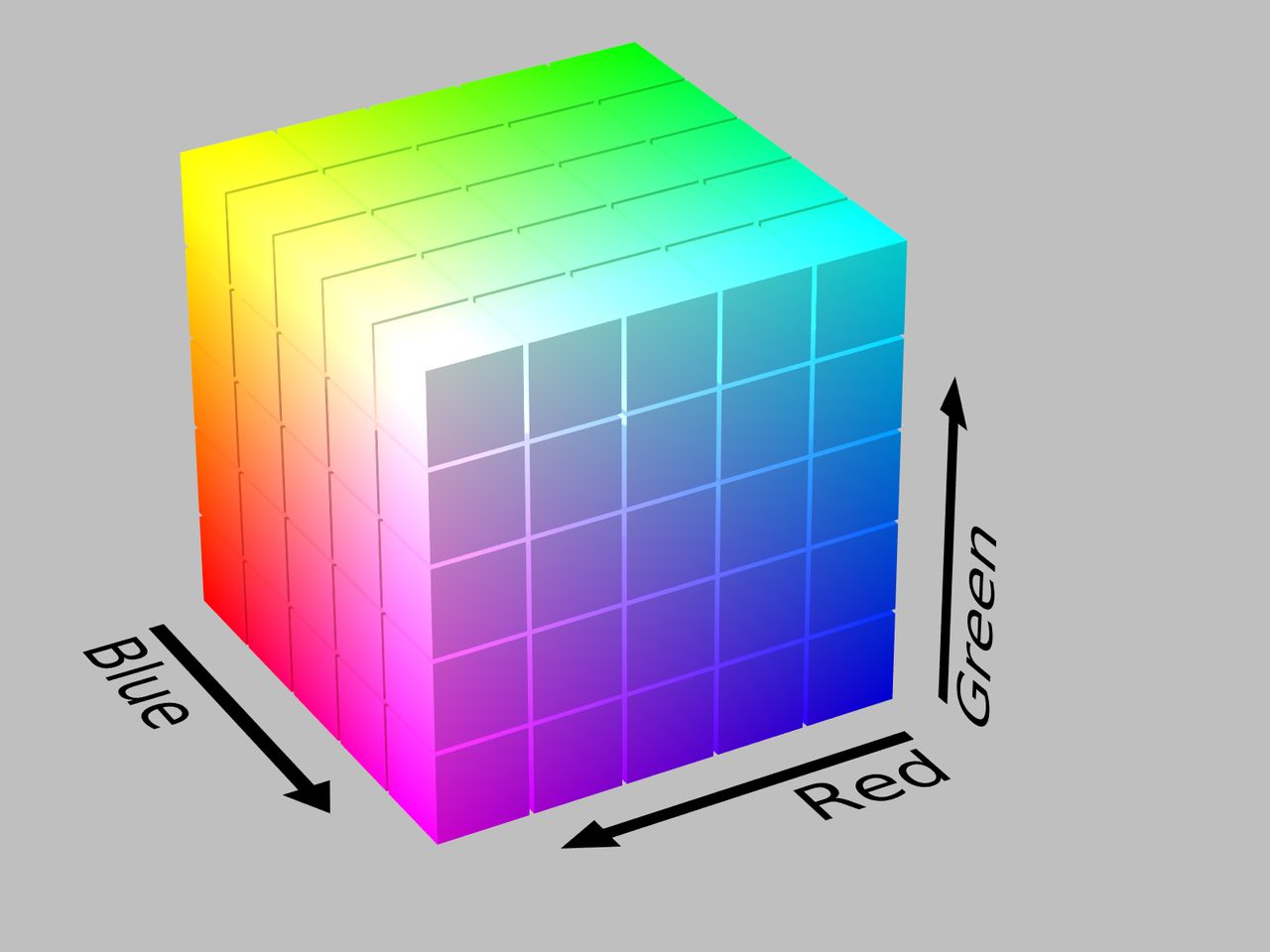

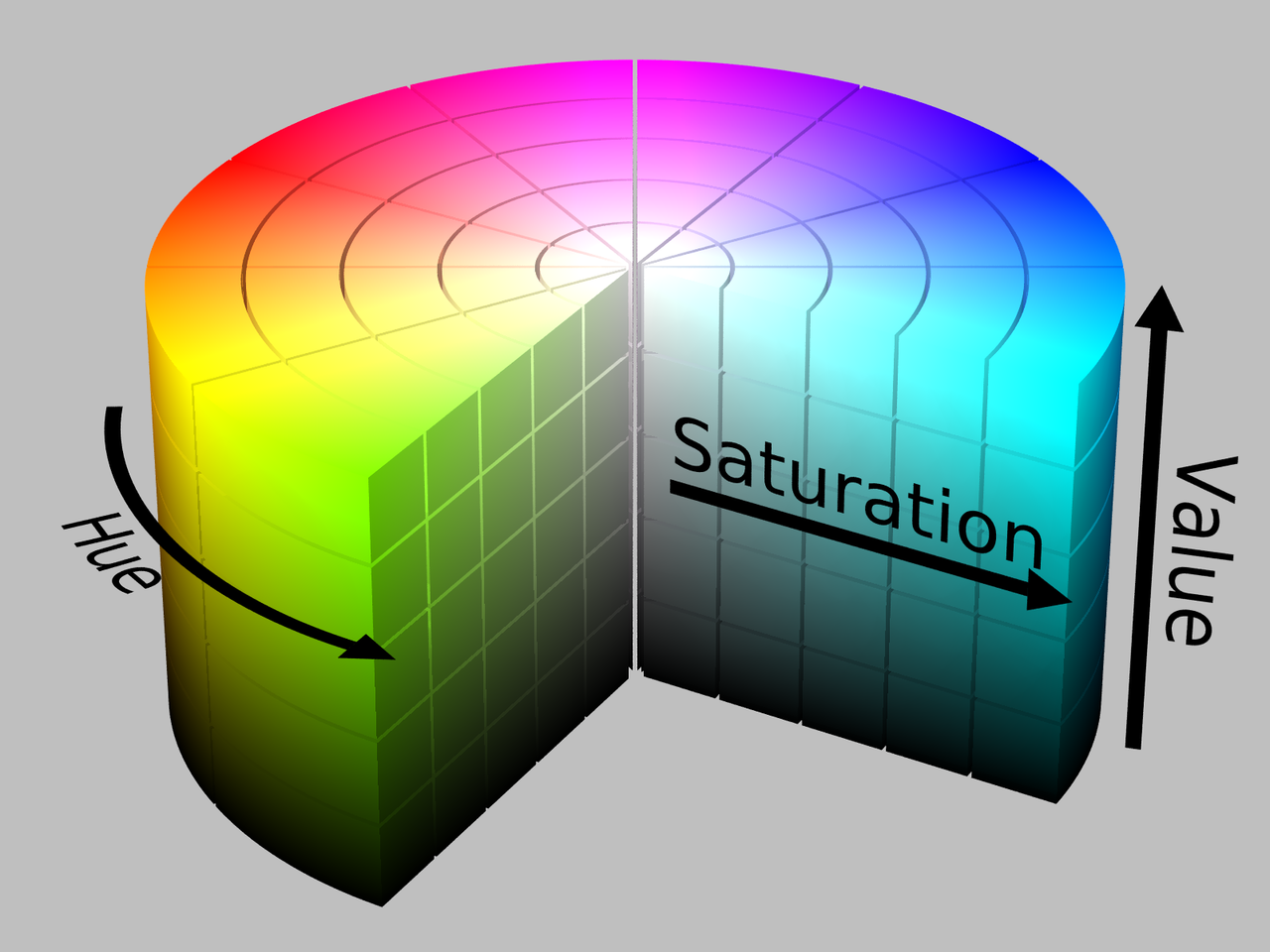

To convert the original images to color maps, we go over each pixel of the original image and replace the pixel’s color with the closet color in the color list. The problem is that calculating the closest color is conceptually wrong because the shortest distance in the color space does not imply that two colors are visually similar. However, this is the best approach for us to generate color maps. To minimize the errors, we experiment with calculating the shortest distance in two different color spaces, which are RGB color space and HSV color space. RGB color space uses three values to mix three lights, which are red, green, and blue, in different proportions. The higher the value is, the brighter the light is. HSV color space uses three values to control three different aspects of the color. The hue (H) specifies the angle of the color on the RGB color circle (hue wheel). The saturation (S) controls the amount of color used. The value (V) controls the brightness of the color. To have an interactive example for different color space, we recommend to visit the website, Color models and color spaces.

For RGB, we calculate the distance using the following formula:

\[distance = sqrt(dr^2 + dg^2 + db^2)\]

For HSV, we calculate the distance using the following formula:

\[HueDistance = min(abs(h_1-h_0), 360 - abs(h_1-h_0))\] \[dh = HueDistance / 180\] \[ds = s_1 - s_0\] \[dv = v_1 - v_0\] \[distance = sqrt(dh^2 + ds^2 + dv^2)\]The results of the different combinations of color lists and color spaces are shown in Fig 9 and Fig 10. We think the color map of RGB 73 is closer to the original image, so we chose to calculate the closet distance in RGB color space from 73 Crayola Crayon Colors in 2020.

Modified StyleGAN/SemanticGAN

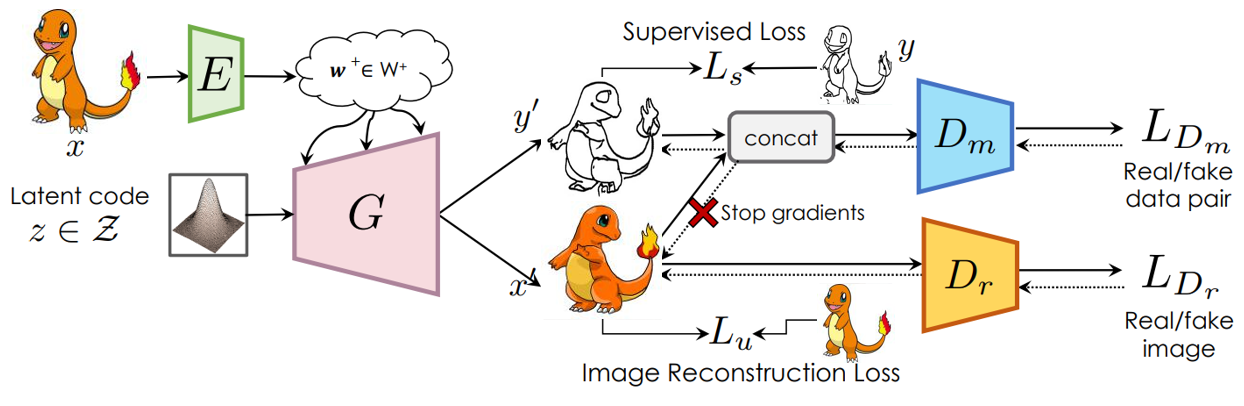

Since we do not have segmentation for Pokemon images, and it is hard to define the segmentation of Pokemon, we decide to replace the segmentation part of SemanticGAN with sketches or color maps. The structures of our model are shown in Fig 11 and Fig 12. The training process of our model is divided into 3 phases.

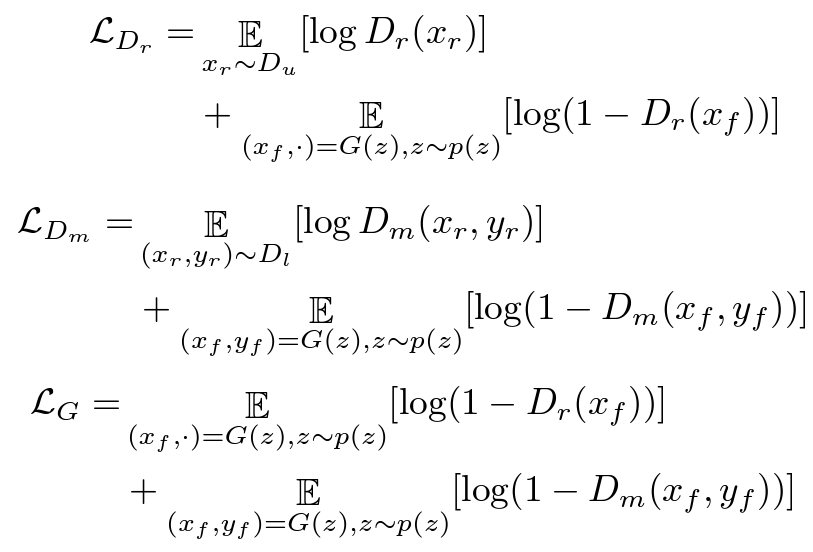

Phase 1: GAN training

The phase 1 is training GAN model. Just like the training of the original StyleGAN or any other GAN model, the two discriminators \(D_r\) and \(D_m\). \(D_r\) is a normal real or fake image discriminator while \(D_m\) is to distinguish between a real or fake pair of image and label map. in this phase, we are simply training StyleGAN with an additional semantic map branch. All the losses are normal GAN losses and are listed below. The only difference is that the mask and image pair discriminator will not pass its gradients back into the image generation branch. You can think of it as the mask generation branch needs to fool the discriminator on its own.

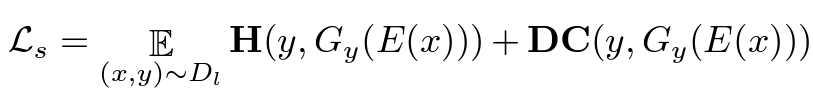

Phase 2: Encoder for Initialization

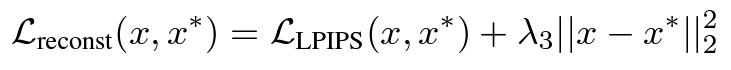

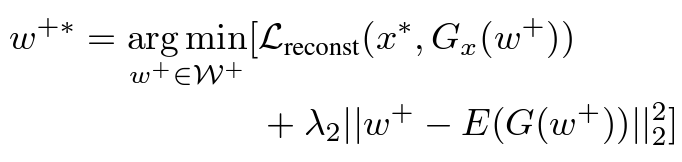

The phase 2 of the training process is to train an encoder that can map a user input image or sketch into the embedding space. When we enter into this phase, the generator is freezed and will not be impacted in this phase. Since StyleGAN are found to perform better with different style modulations for different layers, the encoder \(E\) generates a latent vector \(\mathcal{w}\) for each layer. The objective of this encoder is to find a good latent vector that can make StyleGAN generate an image or sketch similar to the input. This encoder is trained with supervision loss on the mask branch, which includes pixel-wise CE loss and Dice loss. While the image generation branch produces a image reconstruction loss that contains LPIPS a deep perceptual similarity loss based on VGG and a MSE loss.

Phase 3: Infer w+

In phase 3, we will use either a ramdomly sampled or an encoder output as an initial \(\mathcal{w}^+\) in the latent space. Then we would still need to perform some inference steps with the reconstructive loss as a local optimization objective. We have tried to use either the reconstruction loss or relabel loss as the objective when the input is a sketch. And there are more results in the following sessions.

Results

Training Samples

Although the GAN training samples does not have much meaningful shapes, the encoder validation results are rather consistent despite the poor quality of the GAN.

Inference Results

It is obvious that under all settings, the edge map generation result is very accurate. Yet just like what we’ve seen in the sampled results from the training process, the StyleGAN does not have a very meaningful result and it is hard for the encoder to find a good latent vector that both satisfies the edge outline and the high-quality image requirements. And from the top row random initialization setting, we can see that there is latent space where the outline can be very realistic and is slightly shown in the image, but the coloring is completely decoupled from the outline.

Since the sketch encoder is trained to find a latent vector that can both find realistic sketches and images, some coloring is shown on the boundaries of Pokemon. Yet without color information, it is hard for the inference process to find outputs with concrete colors.

When directly using an image to find similar images in the generation. It is obvious that similar images can be found through the encoder initialization and the inference process. Compared to “Sketch Your Own GAN”, the reason that it is hard for our encoder with fewer input signals to find desirable generation seems to be caused by both the decoupling of outline and coloring in the GAN latent space (sketch cannot be an indicator of perceptually equivalent to the image), and the lack of data also make encoder performance deteriorate for unseen data. We can see that the sketch encoder performs rather well for validation data in the previous section. Yet the obvious performance drop in the test data looks like another side effect of data deficiency.

The above plots show more results of image generaion based on our own sketches.

Conclusion

For the results image, we do not achieve a perfect-looking Pokemon. There are three possible reasons. First, the dataset is not large enough, yet the official art of Pokemon is limited. To augment the training dataset, we can try to include the fanart, but the art style might not be the same as the official art. Also, we will need better hardware resources to speed up the training process. The second reason is that we do not train the model long enough. We can tell that the shape and color of Pokemon are gradually formed during the training process. Given the limited time, we only train our model for about a week. We tried to train the model until the due date of the project. However, we encounter environment issues and disconnect from the server we used. If we were able to train the model for a longer time, we might get a better result based on the trend show from the current results. Lastly, color maps may contain too many colors. In the original SemanticGAN paper, their segmentation consists of about 8 colors. 73 colors may be too complicated as labels leading to less generalization of labels.

Nevertheless, our project allows human control in the Pokemon generation process. Humans can choose whether they want to provide the labels to control the output result. To improve the results of this work, we can try to increase the training dataset, increase the train time, label with color maps with a lower number of colors, or come up with different methods to substitute segmentation. Also, having more latent space analysis for SemanticGAN can allow humans to use sliders to control the changing directions of Pokemon. These are the directions for future work to improve the project.

Acknowledgments

Due to personal reasons, Jiayue has to drop this class. However, she contributes to this project a lot, including brainstorming, discussing ideas, and implementing the portion of the project, so I choose to keep her as one of the authors.

Reference

[1] Xie, Saining and Tu, Zhuowen. “Holistically-Nested Edge Detection” Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). 2015.

[2] Li, Mengtian, et al. “Photo-Sketching: Inferring Contour Drawings from Images.” WACV. 2019.

[3] Karras, Tero, Samuli Laine, and Timo Aila. “A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2019.

[4] Karras, Tero, et al. “Analyzing and improving the image quality of stylegan.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2020.

[5] Isola, Phillip, Zhu, Jun-Yan, Zhou, Tinghui, and Efros, A. Alexei. “Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks.” 2016.

[6] Daiqing Li, Junlin Yang, Karsten Kreis, Antonio Torralba, and Sanja Fidler. “Semantic Segmentation with Generative Models: Semi-Supervised Learning and Strong Out-of-Domain Generalization.” 2021.

[7] Crowther, Jenny.” Complete list of Prismacolor Premier Colored Pencils.” Jenny’s Crayon Collection. 2017.

[8] Crowther, Jenny.” Complete list of Prismacolor Premier Colored Pencils.” Jenny’s Crayon Collection. 2020.