Visual Counting

Repetition of a task is quite common in our day to day life ranging from a simple pendulum to the periodic day and night pattern of earth, everything repeats. Counting repetitions through time from a video has interesting applications into healthcare, sports and fitness domains for tracking reps in exercises, shots in a badminton rally etc. Through this project, we would like to explore existing literature towards class agnostic counting from video and specifically apply/invent to a scenario of counting paper bills(currency) from a video. Although machines exist for this particular task, being able to do the same just by using a smartphone camera has its advantages of being widely accessible and availability at low cost. We believe that this task is also a perfect fit for this course as it needs both human and AI collaboration!. We also like to mention that this seemingly simple task might be ambitious to achieve and thereby planning to explore other directions to mould existing counting mechanisms which process video as a whole towards real time counting systems, so that they can be used in day to day life.

- Introduction

- Related Work

- Dataset Collection

- Frequency variation tests

- 1x-Training

- 2x-Training

- Results

- Synthetic/Augmented Data

- Making RepNet Live

- Conclusion & Future Work

- Code & Data

- Note

- References

Introduction

We find that the ability to count repetitive tasks from a video is interesting enough. It has associated challenges that the repetition may not be exact, non-uniform period length of the repeating task, being class agnostic for varied actions, handling high to low frequency task variations and feel it is worth exploring and applying to scenario of counting currency. We think that this task of counting currency is achievable because with introduction of sufficient slow motion in the video, human beings are able to count the number of paper bills exactly (We tried this and are able to do it). As humans(processing power of around 24 fps) are able to do this and latest smartphone camera captures vary around 30-60 fps, we hope its not impossible to achieve this task.

Related Work

In our quest for a system which could possibly count currency flippings from a video, we have come across an interesting paper Counting Out Time: Class Agnostic Video Repetition Counting in the Wild [1] which uses a specialised neural net architecture called ‘RepNet’ to count the repeating task in a video. Below we will go through a brief study of this paper, describing its architecture, training, results and its performance on our expected task of counting.

RepNet: Class Agnostic Video Repetition Counting in the Wild

Architecture

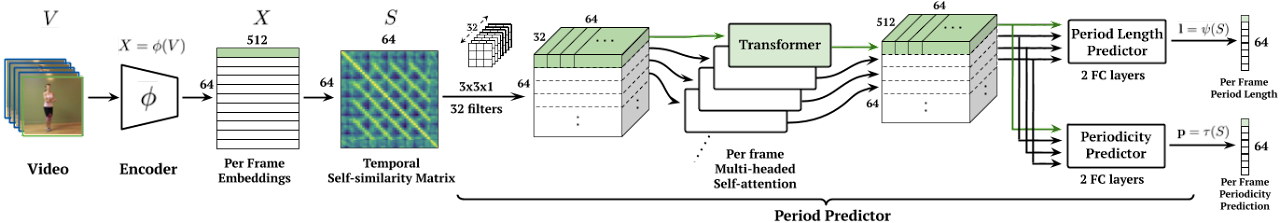

Figure 1. RepNet Architecture [1]

Figure 1. RepNet Architecture [1]

The first part of the architecture is to embed the input frames into a 512 dimentional feature vector and create a Temporal Self Similarity Matrix(TSM). A TSM can be thought of as an indicator to measure similarity of the video frames within itself, essentially the \((i, j)'th\) element of TSM \((TSM[i][j])\), represents the similarity score between frame \(i\) and frame \(j\) in the input video. This particular idea of using a TSM differentiates this work from others and accounts for its class agnostic nature, we do not need to care about the task which is going on, all we need is its similarity through time!!

The next part is to pass the created TSM as an input to a Transformer based deep neural network(referred as ‘Period Predictor’) to predict the period length and periodicity for each frame. Period length is a discrete quantity \(\in \{2,3,...,\frac{N}{2}\}\) where \(N\) represents the number of input frames, where as Periodicity is a binary quantity \(\in \{0,1\}\) indicating whether a frame is part of the repeating task or not.

Data && Training

In order to train this network, they have created a synthetic dataset called Countix, consisting of real life repeating actions covering diverse set of periods and counts. The dataset is synthetic in a sense that certain actions from Kinetics[2] dataset are selected and their annotated segments are used to create repetition videos by joining same segment multiple times by varying in frequency, reversing the action video etc. The created videos are approximately around 10 seconds. The model is trained for 400K steps with learning rate of \(6e^{-6}\), using ADAM optimizer and bacth size of 5 videos each with 64 frames.

Evaluation Metrics

The existing literature uses two main metrics for evaluating repetition counting in videos:

Off-By-One (OBO) count error: If the predicted count is within one count of the ground truth value, then the video is considered to be classified correctly, otherwise it is a mis-classification. The OBO error is the mis-classification rate over the entire dataset.

Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of count: This metric measures the absolute difference between the ground truth count and the predicted count, and then normalizes it by dividing with the ground truth count. The reported MAE error is the mean of the normalized absolute differences over the entire dataset.

Results

The paper presents promising results on some actions like jumping jacks, squats, slicing onion etc. The counts are also near perfect in cases of varying periodicity and change of tempo in the repetitions. It also mentions lower error metrics, MAE and OBO of 0.104 and 0.17 respectively while comparing with other methods. Some of the tasks on which the count is accurate are shown below.

Figure 2. RepNet results [1]

Figure 2. RepNet results [1]

Performance on our task

We have tested the model on our task of counting currency. As currency bundles are not easily available :(, we just have 1-2 videos of currency flipping for now. Instead of currency, we are targeting the count of paper flippings. Below we show the results of running RepNet on few videos related to our case. AC stands for Actual Count, PC for Predicted Count.

currency - normal speed

30 fps | AC > 41 | PC = 28

book pages - slow

30 fps | AC > 0 | PC = 0

book pages - very slow

30 fps | AC = 20 | PC = 18

Figure 3. Videos showing performance of RepNet on currency/book-page-flip counting task

Dataset Collection

As currency notes are not widely available, we stick to predicting count in paper flipping videos of books, which could be easily generalised later to currency counting as both the tasks share similar structure. As a first step, we have collected 50 videos of book-page flipping by varying the books, backgrounds, flipping-speed from the UCLA Library and around 20 videos from various places. Then, we carefully labelled the ground truth count for these videos by appropiately slowing down the videos. The video links in the following table summarises some of our data collection. This short video dataset will be used for analysis and evaluation purposes.

| duration | fps | flip-freq | repnet-count | actual-count | details-(human) | repnet-link | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VID_slow | 21s | 30 | 1 | 17 | 21 | not slowed | here |

| VID_medium | 21s | 30 | 1.47 | 15 | 31 | 21s - 1.24s slowed(25%) | here |

| VID_fast | 22s | 30 | 1.95 | 32 | 43 | 22s - 1.28s slowed(25%) | here |

| VID_ultrafast | 22s | 30 | 4.91 | 40 | 108 | 22s - 3.36s slowed(10%) | here |

| VID_workout | 30s | 30 | 0.67 | 16 | 20 | not slowed | here |

Table 1. A sample of videos from book-dataset with corresponding attributes

Complete book-dataset collected from UCLA Library can be found here

Frequency variation tests

Let us take a task on which the RepNet works well. Try speeding up the video so that the task looks more frequent and check the performance. Also will pick a task from above on which the performance is poor (VID_medium), slow down the video to see if the predictions improve.

The following table summarises frequency variation for a humming bird

Figure 4. Visualisation of humming bird in 1x and 8x respectively

| 1x-speed | 2x-speed | 3x-speed | 4x-speed | 8x-speed | 16x-speed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VID_humming | here | here | here | here | here | here |

| actual-count | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 |

| repnet-count | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 0 |

| video-time | 10s | 5s | 3.3s | 2.5s | 1.25s | 0.625s |

| frequency(reps/sec) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 12.8 |

Table 2. Working of RepNet on varied frequency of humming bird task

Similarly, we slow down one of our fast videos(of paper flipping) and see how repnet performs.

Figure 5. Visualisation of one of the book page flipping video which is slowed for frequency variation tests

| 1x-slow | 2x-slow | 4x-slow | 10x-slow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VID_medium | here | here | here | here |

| actual-count | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 |

| repnet-count | 15 | 16 | 16 | 14 |

| video-time | 21s | 42s | 1:25s | 3:31s |

| frequency(reps/sec) | 1.48 | 0.74 | 0.36 | 0.15 |

Table 3. Working of RepNet on varied frequency of book page flipping task

From the above observations, it seems that even varied frequency videos has similar prediction. So the inherent issue with bad prediction for paper-flip counting is possibly because of 2 reasons.

-

Flipping is not actually a full periodic motion(the pages won’t come back to original position), but successive flipping has similarities (may be we can call it pseudo-periodic). So the similarity calcultion between frames might not be as good as for periodic motions.

-

The trained network might not have seen this kind of videos (or fast ones in general), and TSM’s for these might not be obvious for the network to predict correct count.

Based on the above assumptions, the first one can only be handled by including book-flipping like pseudo-periodic tasks in the training set. The dataset we have currently(~50 videos) is not concretely enough to capture all variations and we will explore this in later sections as time permits. In order to account for the second reason, we next train the network using higher frequency videos.

1x-Training

We have reproduced the model in PyTorch so that we have much more flexibility to modify according to our needs for making it live(as Tensorflow models have significant issues running on normal computers), as well as for high-frequency training.

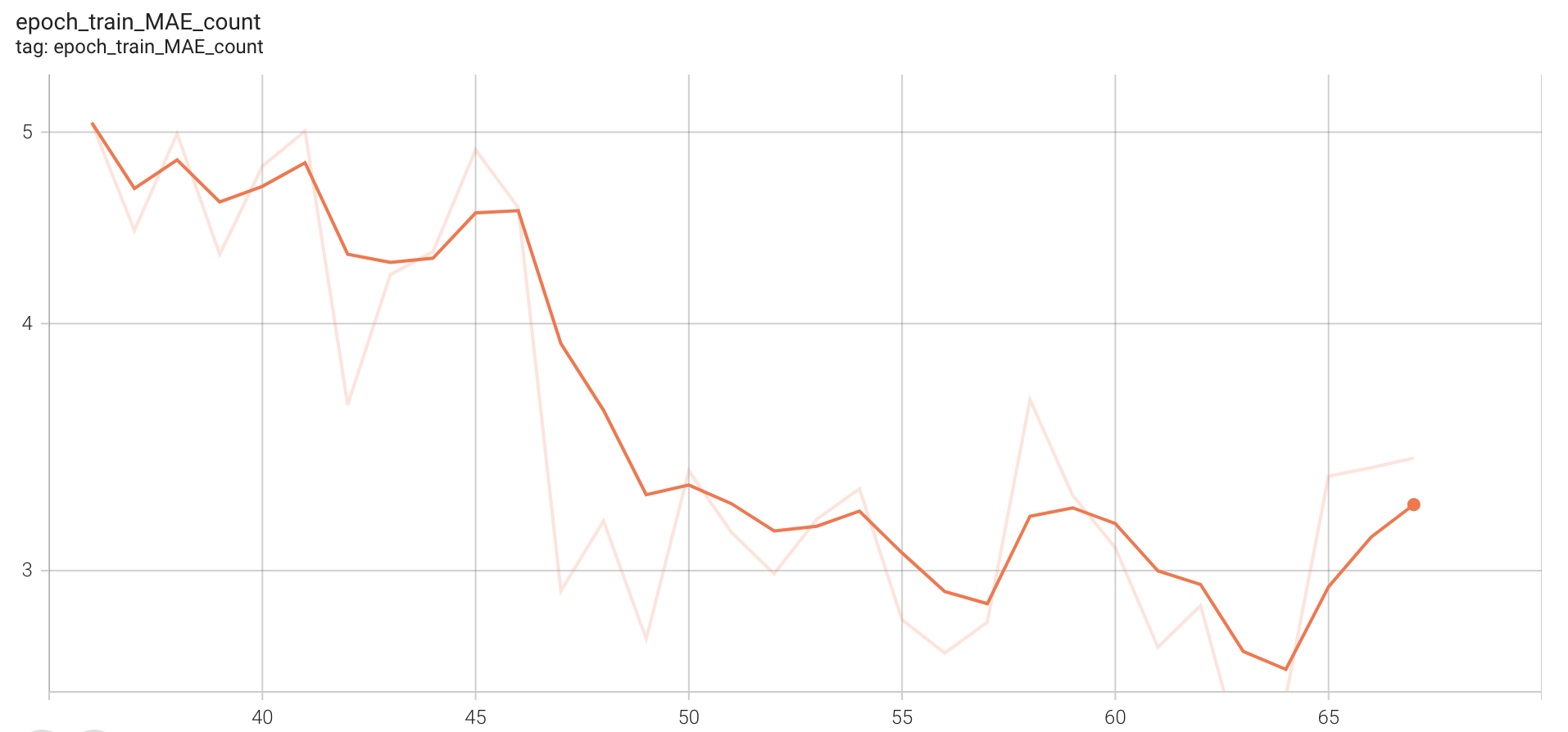

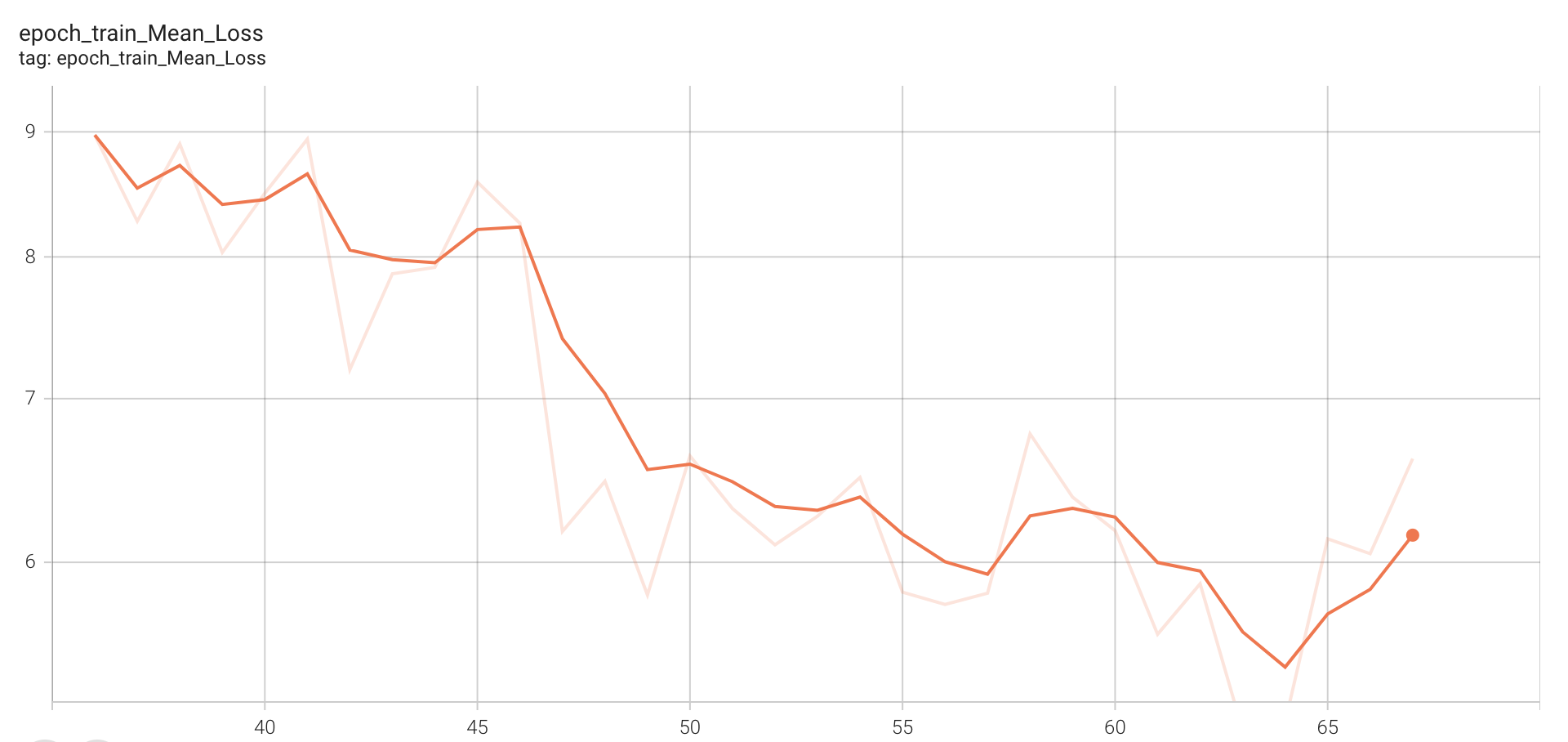

For this, we used the Countix dataset which consists of ~4800 train and ~2400 test videos of various repeating actions. A training data point consists of 64 frames(at equal distance) sampled from the video and their label is the per frame period (total frames/actual count). Using ADAM optimizer with learning rate of \(5e^{-6}\), batch size of 8, we were able to train the model for 67 epochs in total on half the Countix dataset. Each epoch takes approximately 40 minutes and hence we are limited by the resources we have. Below figures show our train curves for Mean Absolute Error(MAE) of count, period and total loss respectively.

Train MAE count

Figure 6. Training curve representing MAE count

Figure 6. Training curve representing MAE count

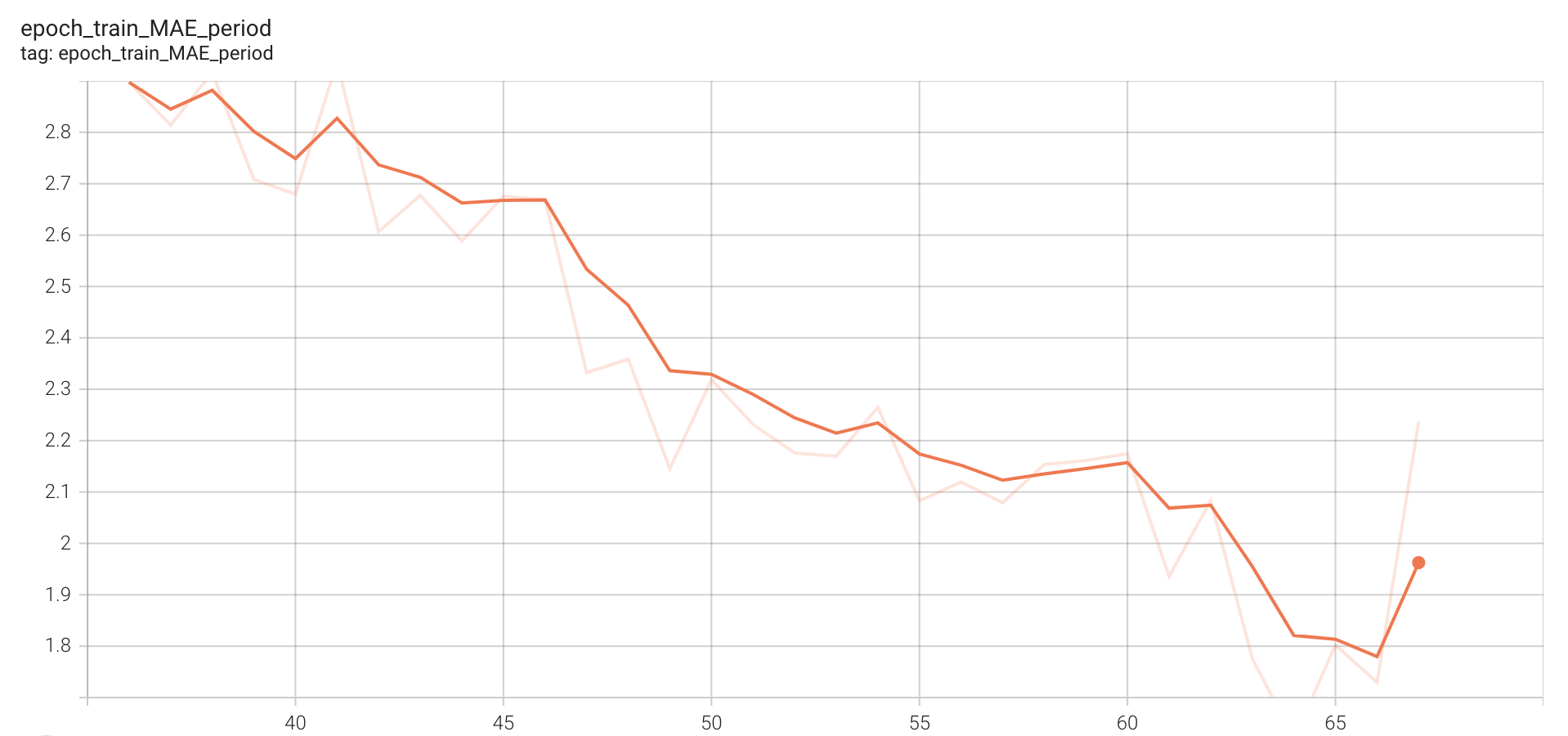

Train MAE period

Figure 7. Training curve representing MAE period

Figure 7. Training curve representing MAE period

Train Mean Loss

Figure 8. Training curve representing mean overall loss

Figure 8. Training curve representing mean overall loss

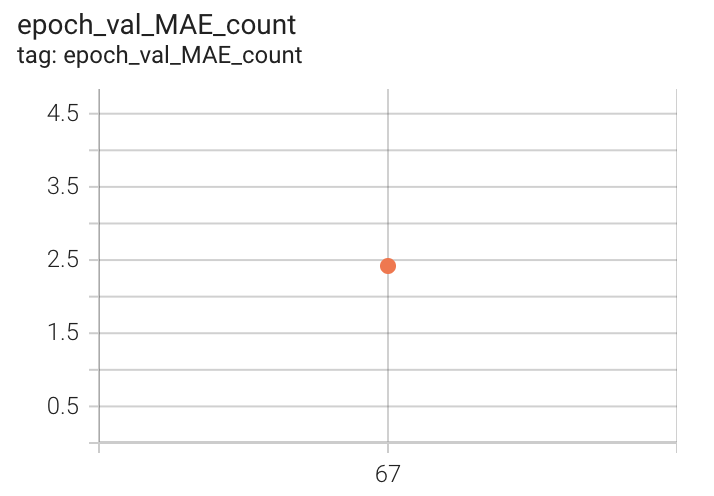

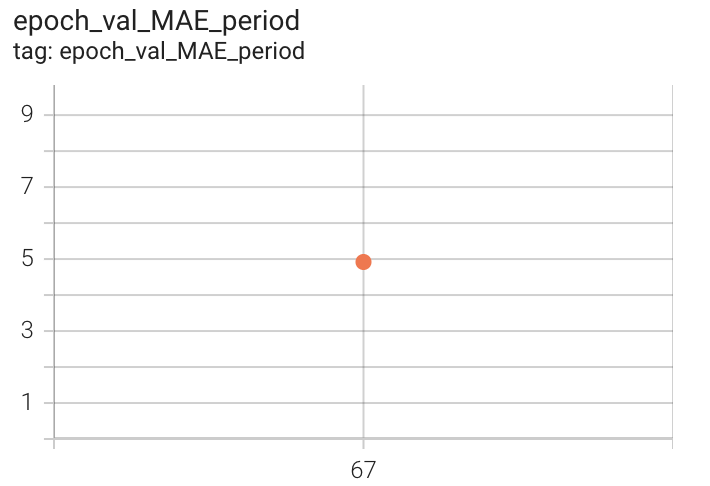

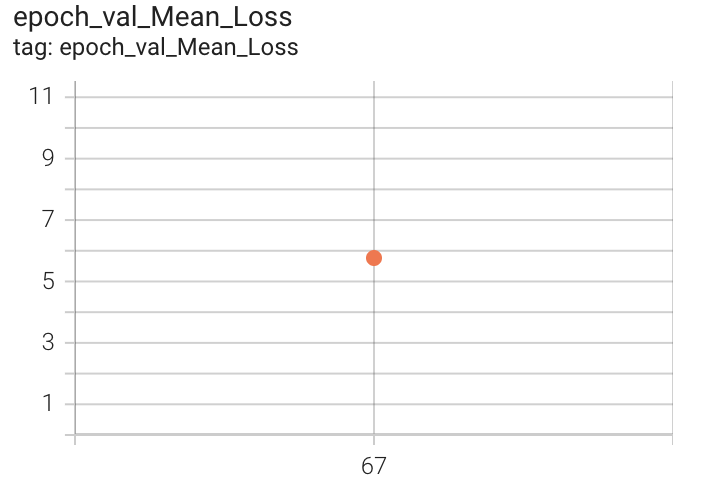

The final MAE on count for train data is around 3.5. Due to resource constraints, we have only validated our model on the test set at end of 67 epochs. The following figures show various losses on the test(validation) set(~2400 videos).

| Validation MAE count | Validation MAE period | Validation Mean Loss |

|

|

|

Figure 9. MAE count, period and Mean Loss Countix Test set after 67 epochs of 1x-training

The RepNet paper reports a validation MAE count of around 0.3 on training for ~400K steps, we see that our validation MAE count is around 2.5, which is a reasonable score to attain by just training for 67 epochs. We have spent around 8-12 days for this training as colab-pro has resource/session limitations. Code for dataset, train, inference and evaluation related to our 1x-training can be found here

2x-Training

To train the model on high frequency tasks, we have used a technique to double up the count in each video by making it 2x faster within the 64 frames. We take a single video, concatenate the video with itself to create longer one with double the count and sample 64 frames from this longer video. Effectively, we get a 2x faster video having 2x action repetitions in the same 64 frame length. Below, we show a training sample from original setting and our 2x-setting.

|

|

| 1x-setting | 2x-setting |

| frames : 64 | frames : 64 |

| count : 7 | count : 14 |

Figure 10. Same training sample from 1x, 2x training respectively

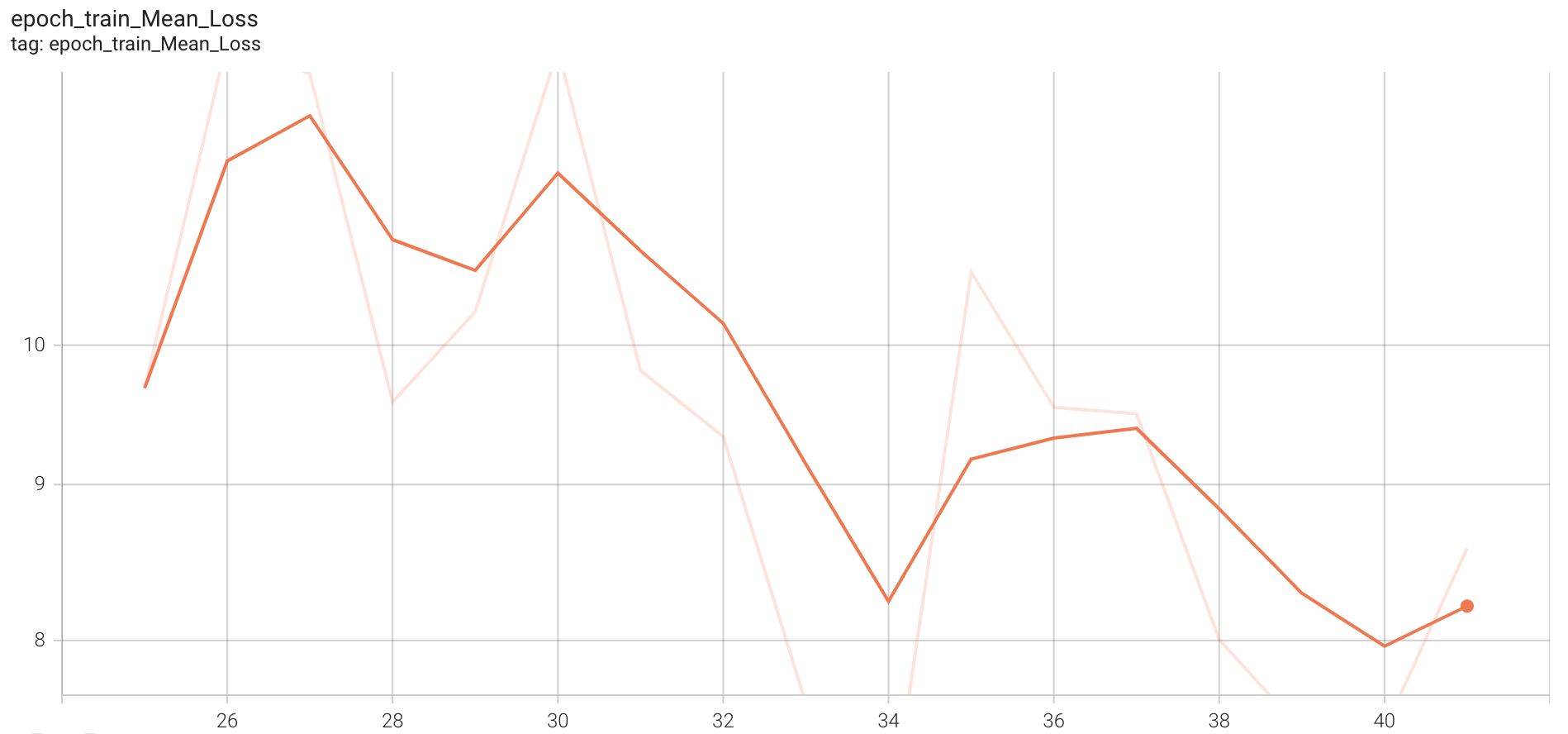

For training, similar parameters as earlier were maintained except that we trained on whole of Countix dataset this time. Each epoch took around 1 hour on colab-pro and we have trained for a total of 41 epochs. Below figures show the training curves from epoch 25 as we had lost the metrics in between due to errors and had to correct learning rate.

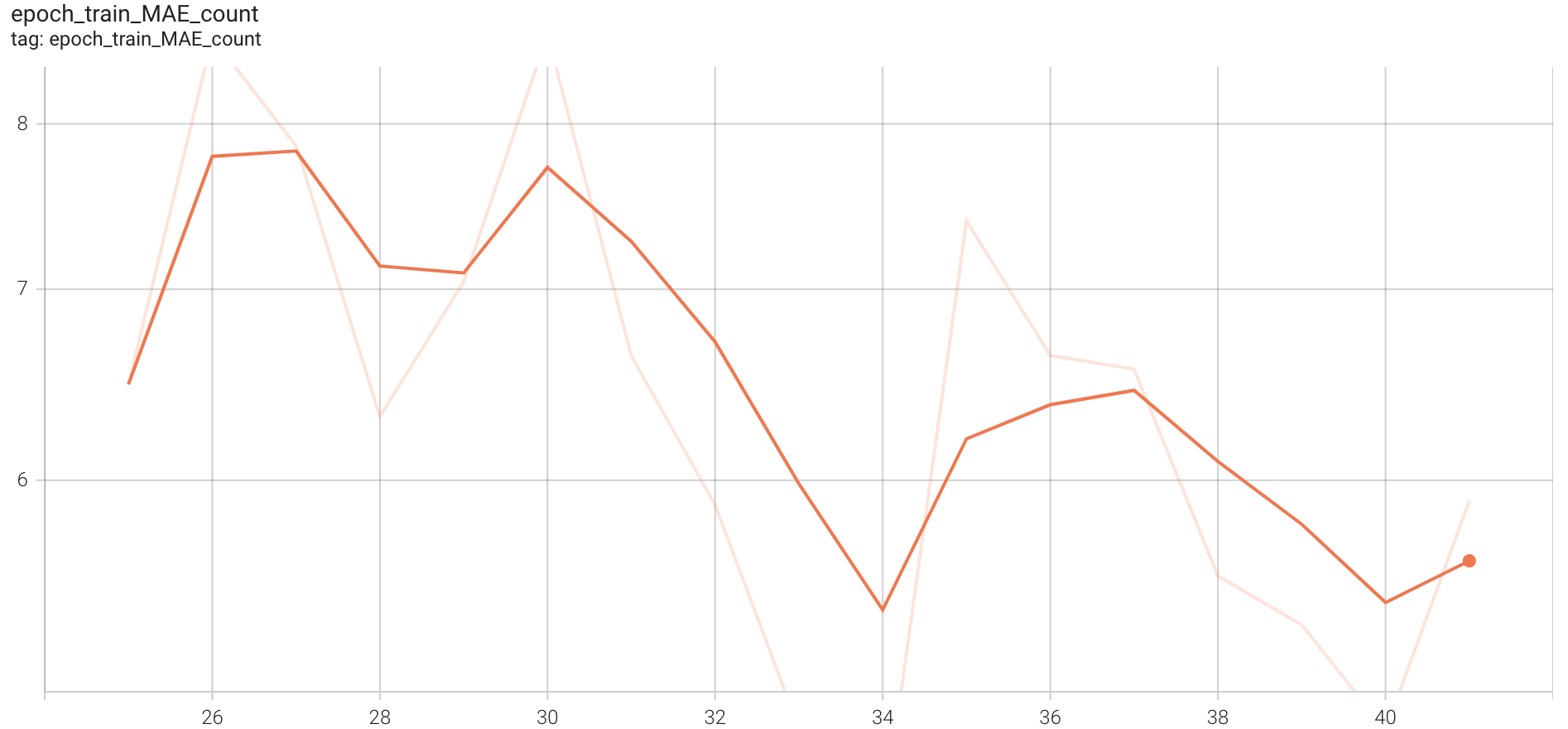

Train MAE Count

Figure 11. Training curve representing MAE count

Figure 11. Training curve representing MAE count

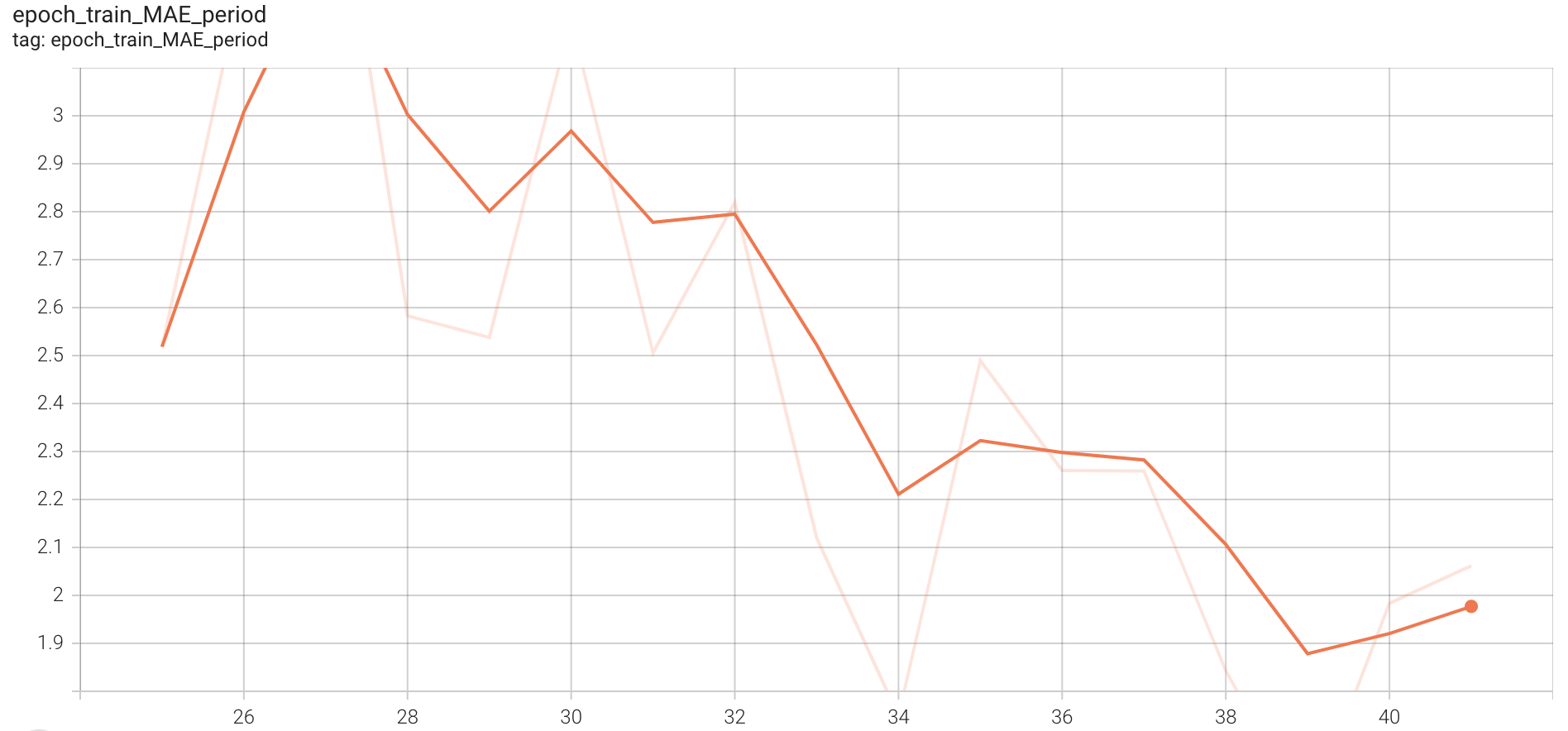

Train MAE Period

Figure 12. Training curve representing MAE period

Figure 12. Training curve representing MAE period

Train Mean Loss

Figure 13. Training curve representing mean overall loss

Figure 13. Training curve representing mean overall loss

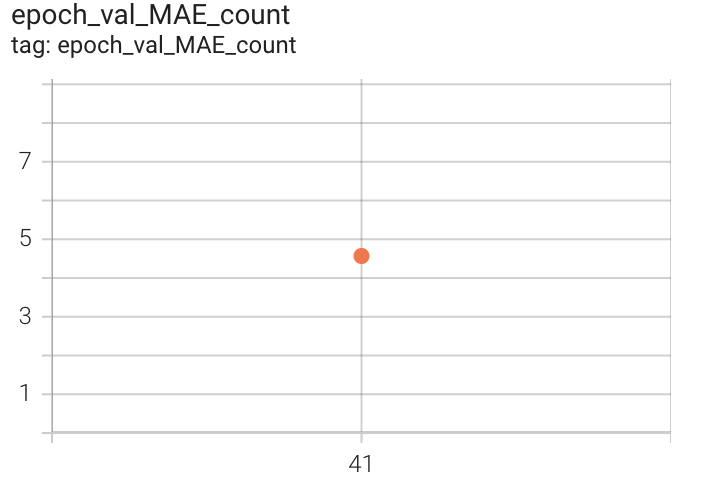

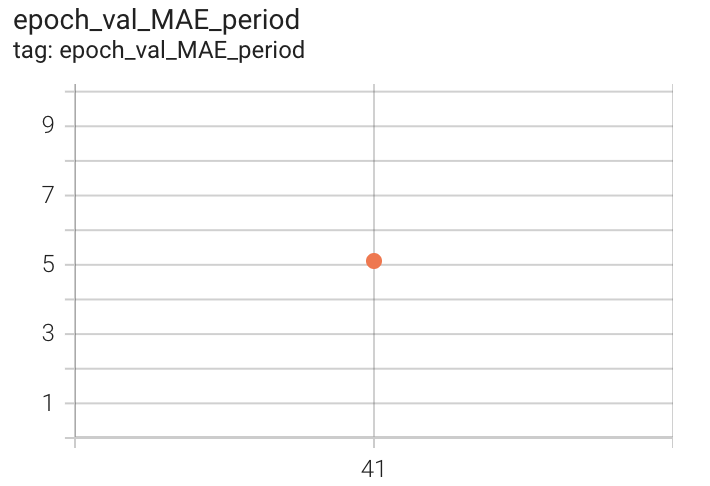

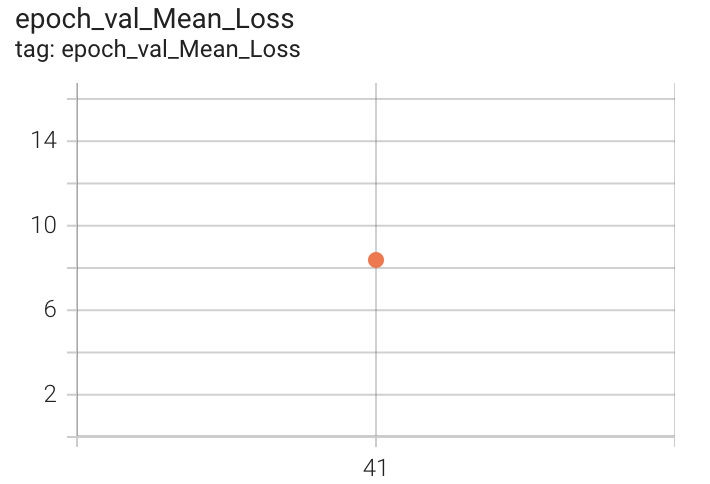

The final MAE on count for train data is around 5.6. The following figures show various losses on the test(validation) set(~2400 videos) of this model after 41 epochs.

| Validation MAE count | Validation MAE period | Validation Mean Loss |

|

|

|

Figure 14. MAE count, period and Mean Loss on Countix Test set after 41 epochs of 2x-training

The obtained validation MAE count is 4.5. Code related to our 2x-training can be found here

Results

After finishing the 1x-training and 2x-training to 67 and 41 epochs respectively, we have tested both the models on our collected book-dataset. The following table summarises MAE count.

| Countix Test Data | Book Dataset | |

|---|---|---|

| 1x-training | 2.5 | 4.35 |

| 2x-training | 4.5 | 3.95 |

Table 4. Results of 1x-training, 2x-training on Countix Test, Book-Dataset

Note that no data from book dataset is used during training. The results indicate that 2x-training is not that better on regular videos, but is slightly better in case of the book dataset we collected which contain faster repetitions. However, we cannot take this as enough improvement as many counts are still off from the ground truth and more interesting error metrics like Off By One(OBO) might be useful for further conclusion.

Surprisingly, we have obtained MAE count of 8.5 on book-dataset using the trained model made available by the authors of RepNet. It looks like our training procedure somehow benefits or is better at book-dataset count predictions :)

Synthetic/Augmented Data

To address the issue of pseudo-periodic motion rather than periodic ones(as described in earlier sections), it might be useful to include such data during training. Also the current Countix dataset do not have any flipping like actions, so adding page flipping videos along with ground truth might help the model learn better for these scenarios. However we do not have enough data in this regard. Here, we propose a new method to generate 10x more videos from existing dataset.

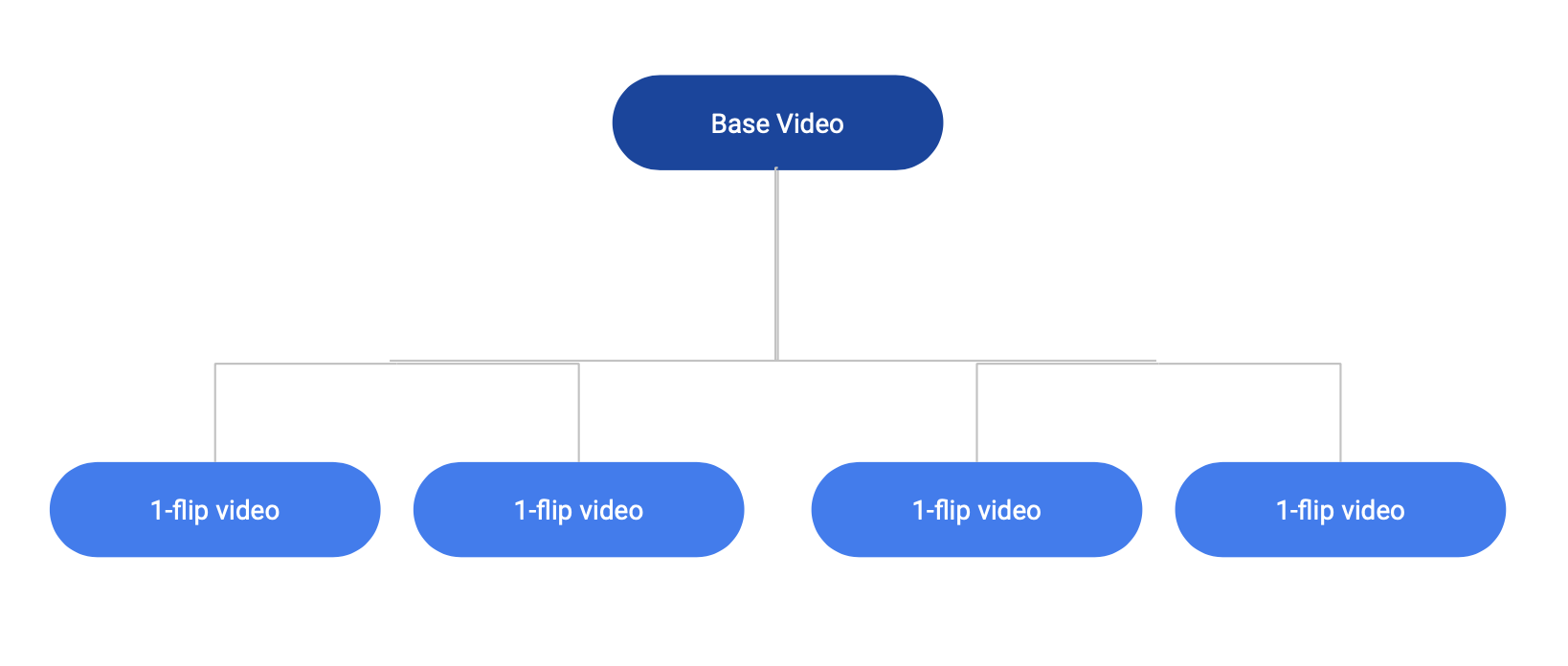

From a base video of original book page flipping, we label several segments(~10) each of which containing a single page flip(we call it 1-flip from now). We trim out these 1-flip videos from the base video into a pool for further usage. Next we repeat the following steps to genrate multiple videos containing varied flip-speeds and counts.

Figure 15. Graphical representation of synthetic data generation process

Figure 15. Graphical representation of synthetic data generation process

- Pick a random count(>1)

- For count number of steps

a. Pick a 1-flip video at random from the pool.

b. Modify the speed of 1-flip(make it 2x, 3x faster or slower) at random.

c. Add minimal random noise throught all the frames so that we do not miss the flip-action. - Join all the above 1-flip videos to create a brand new book page flipping video.

Figure shows a graphical description of this process. Because the videos we are joining contains a single flip, we precisely know the ground truth count for each of the generated video. We can use the above method to genrate at least 10 or more varied videos from a single base video. The following videos are generated using the above method.

count : 9

count : 21

Figure 16. Two of the synthetically generated videos

Clearly the generated videos look a bit realistic and we stongly believe that these can be used for training. Our collected dataset has ~50 videos, and using the above method we can generate and make around 750 videos which should be good enough for basic training. We could not setup this training yet due to the immense hardness/time bound to label single page flips from base video for all 50 videos.

Early code related to synthetic-data generation can be found here

Making RepNet Live

Next, we describe our efforts to make the model live so that people can run it on their laptops or mobile devices without the need for costly computational resources like GPU.

Limitations with the existing model

Existing model first takes the complete video then do the counting on it. It would be widely useful in a wide variety of applications in fitness domains etc. to make it real time. We wanted the counts to be shown at the same time when the video is being recorded which the current model lacks.

Approach to make the model live

The existing model is in Tensorflow. We faced a lot of issues with the existing Tensorflow model as the Tensorflow models are not compatible with M1 mac chip. Moreover, on normal laptops it was taking high memory and high amount of time for inference. So we moved to Pytorch based model and trained for 67 epochs on half size dataset of Countix.

Current Model takes about 0.98 seconds for inference on 64 frames. So if we do it sequentially by capturing the live video and call the inference every 64 frames, we need to drop several frames to account for the inference time (camera capture frezees until the inference is complete).

To avoid the drop of frames, we took the Parallel processing approach. We started two processes and established a communication pipe between these two processes. One process was responsible for recording the video from webcam and sending the recorded frames to another process through the communication pipe. The other process will receive the frame , keep checking the length of the frames and as it gets 64, it will call the function to calculate the counts till the current time.

This approach was succesful in making the model live. We observed that due to the communication between two process the frames are not sent at the same speed as they are being recorded so our model was live but still it has a bit of lag.

Approaches taken to make the model faster

We also tried out the pruning technique hoping to reduce the inference time further. It turned out that, it only reduced the compressed model size(compression algorithms are extremely efficient at serializing patterns containing strides of zeroes.) but did not reduce the inference time. A dense tensor filled with zeroes is not any faster to compute, it needs to be converted to a sparse tensor. This would be fine if PyTorch had robust support for sparse tensors, but unfortunately this is not the case currently.

Demo

After setting up the whole pipeline from model training to parallel processing, here we show a demo of the live model on a normal computer(Mac Book Pro) with i5-processor and 8 GB RAM.

Figure 17. Demo video of Live counting

Transferring the model to mobile

We are also working to transfer our model to a mobile app. As we are not that experienced with mobile app development, we had to do a significant background research which we discuss below.

Scripted model Generation

Pytorch provides tools to incrementally transition a model from a pure Python program to a Torch Script program This provides a way to export the model via TorchScript to a production environment where Python programs may be disadvantageous for performance and multi-threading reasons.

Optimizing the trained model for mobile inference

To decrease the inference time of a model, Conv2D + BatchNorm fusion is an important technique. Fusing adjacent convolution and batch norm layers together is typically an inference-time optimization to improve run-time. It is usually achieved by eliminating the batch norm layer entirely and updating the weight and bias of the preceding convolution [0]. The idea behind this optimization is to see that both convolution and batch norm (as well as many other ops) need to save a copy of their input during forward for the backward pass. For large batch sizes, these saved inputs are responsible for most of the memory usage, so being able to avoid allocating another input tensor for every convolution batch norm pair can be a significant reduction.

ReLU and hard tanh fusion which rewrites graph by finding ReLU/hardtanh ops and fuses them together also helps in inference time reduction. There is also Dropout removal technique which removes dropout nodes from this module when training is false.

Saving the model in the lite interpreter format

PyTorch Lite models are basically ZIP archives that contain mostly uncompressed files. In addition, a PyTorch Lite model is also a normal TorchScript serialized model. It can be loaded as a normal TorchScript model using torch.jit.load.

Deploy in mobile app using PyTorch Mobile API - Pytorch Live

The final step is the deployment with the help of Pytorch Live. PyTorch Live is a set of tools to build AI-powered experiences for mobile. It’s apps may target Android 10.0 (API 21) and iOS 12.0 or newer versions.

Conclusion & Future Work

We started with an interesting and challenging task of counting currency/book-paper flips. We have made decent enough progress in that direction. Our contributions include collecting and labelling a dataset of book-page flipping videos, reproducing existing model in PyTorch, better results on book-dataset using 2x-training, a method to generate augmented/synthetic data for page flipping videos and successfull conversion of the existing model to live model. In future, we plan to finish our section labelling task and use the synthetic data for training. Also, currently our model is live on laptop, we have done all the background research to move the model to mobile application. We hope to develop a mobile app which can do live counting.

Code & Data

- Book-Dataset - Google Drive Link

- 1x-training - Colab Link

- 2x-training - Colab Link

- Synthetic-Data-Generation - Colab Link

- Live Counting Repository - Github Link

- RepNet Testing - Colab Link

Note

We are open for ideas, suggestions for this project. Feel free to comment or reach out in case you have some related interesting things to discuss or if you find any papers which might be relevant to solving this particular problem :)

Contact : srinath@g.ucla.edu, soniajaiswal@g.ucla.edu

References

[1] Dwibedi, Debidatta, et al. “Counting out time: Class agnostic video repetition counting in the wild.” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2020.

[2] Kay, Will, et al. “The kinetics human action video dataset.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1705.06950 (2017).

[3] https://pytorch.org/mobile/home/

[4] Yu, Liguo. (2009). Operating System Process Management and the Effect on Maintenance: A Comparison of Linux, FreeBSD, and Darwin.

[5] Vadera, Sunil, and Salem Ameen. “Methods for pruning deep neural networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.00241 (2020).

[6] https://github.com/confifu/RepNet-Pytorch.git