Module 1: Human-AI Collaborated Generation: From Programming to Creativity

In this report, we focus on a special topic in Human-AI Collaboration: Human-AI Collaborated Generation, including Human-AI Programming and Human-AI Co-Creation. We aim to answer 2 questions: 1). To what extent is the ongoing collaboration between human and AI systems? 2). Does AI or human contribute more to the collaboration task? Through a thorough survey of related works, we find currently human plays the leading role in both tasks, but the level of collaboration differs in the two tasks. Future works need to strengthen AI’s abilities on generation tasks as well as improve the communication between humans and AI during collaboration.

Introduction

In recent years, Artificial Intelligence(AI) technologies’ striking performance has drawn people’s attention to a new area “Human-AI Collaboration”, where human and AI work together towards a shared goal. Various forms of collaboration were achieved on an array of tasks, including programming, artistic creation, medical diagnosis, virtual assistants, autonomous driving, teaching, and decision-making. These tasks could further be categorized as the classification task and generation task. The former usually requires a “human+AI” team to make correct predictions before taking action, while the latter needs human-AI teamwork on producing fit-for-purpose or creative content.

In this survey, we will focus on human-AI collaborated generation tasks, where human and AI work jointly to create visual, audio, or text contents, such as code, stories, poems, paintings, and music. Generation tasks are challenging for both human and AI, as it involves multiple steps before completion, communications between teammates, observations of existing work, imitations of examples, and production of new content. It is also hard to have explicit criteria of “good generations” in many situations, which leads to difficulties in improving human-AI collaborated generation. Delving into such a challenging but intriguing area, we hope to answer 2 questions:

-

To what extent is the ongoing collaboration between human and AI on generation tasks?

-

Does AI or human contribute more in human-AI generation tasks?

Our investigation was centered on two streams of generation tasks: human-AI programming and human-AI co-creation. We will introduce the current progress, as well as the limitations and future directions. We hope to extract common insights from these two streams of tasks, and shed light on the future of human-AI collaboration.

Human-AI Programming

Computer programming is the process of performing a particular task by building an executable computer program. Once a programmer knows what to build, the act of programming can be thought of in 2 steps: 1). breaking a problem down into simpler problems; 2). mapping those simple problems to existing code (libraries, APIs, or functions) that already exist1. The latter is often the least fun part of programming (some repetitive/redundant work) and the highest barrier to entry (depends on proficiency in a programming language). This makes people think: can AI help human do programming such “boring” yet important tasks? The answer is affirmative. With the eye-catching success of AI models (especially large language models) in many domains[1-6] and the presence of code in large datasets[7], as well as the resulting programming capabilities of language models trained on these datasets[8], these models have also gradually been applied to program synthesis[9], i.e. AI models collaborate with human to do programming, namely Human-AI Programming

Current Progress

Traditional program synthesis is usually from a natural language specification through utilizing a probabilistic context free grammar (PCFG) to generate a program’s abstract syntax tree (AST)[10-13]. With the resurgence of deep learning and the success of large language models[14, 15], large-scale Transformers have also been applied to program synthesis. CodeBERT[16] is based on Transformer neural architecture and has been trained with a hybrid objective function, to learn general-purpose representations that support downstream applications such as code search, code documentation generation, etc. PyMT5[17] is a text-to-text transfer transformer especially for the PYTHON method, to translate between all pairs of PYTHON method feature combinations(non-overlapping subsets of signature, docstring, body). Similar in spirit to PyMT5[17], Codex[18] is a GPT language model fine-tuned on publicly available code from GitHub, which displayed strong performance on HumanEval dataset (including a set of 164 hand-written programming problems).Codex[18] is most capable in Python, but it is also proficient in over a dozen languages including JavaScript, Go, Perl, PHP, Ruby, Swift and TypeScript, and even Shell, whose descendants power GitHub Copilot2, an AI pair programmer that helps human write code faster and with less work. More recently, AlphaCode[19] shows more complex programming ability, which focuses on competition-level code generation and achieves on average a ranking of the top 54.3% in competitions on the Codeforces platform. CODEGEN [20] is a conversational program synthesis approach via large language models, which casts the process of writing a specification and program as a multi-turn conversation between a user and a system, outperforming Codex [18] on the HumanEval benchmark.

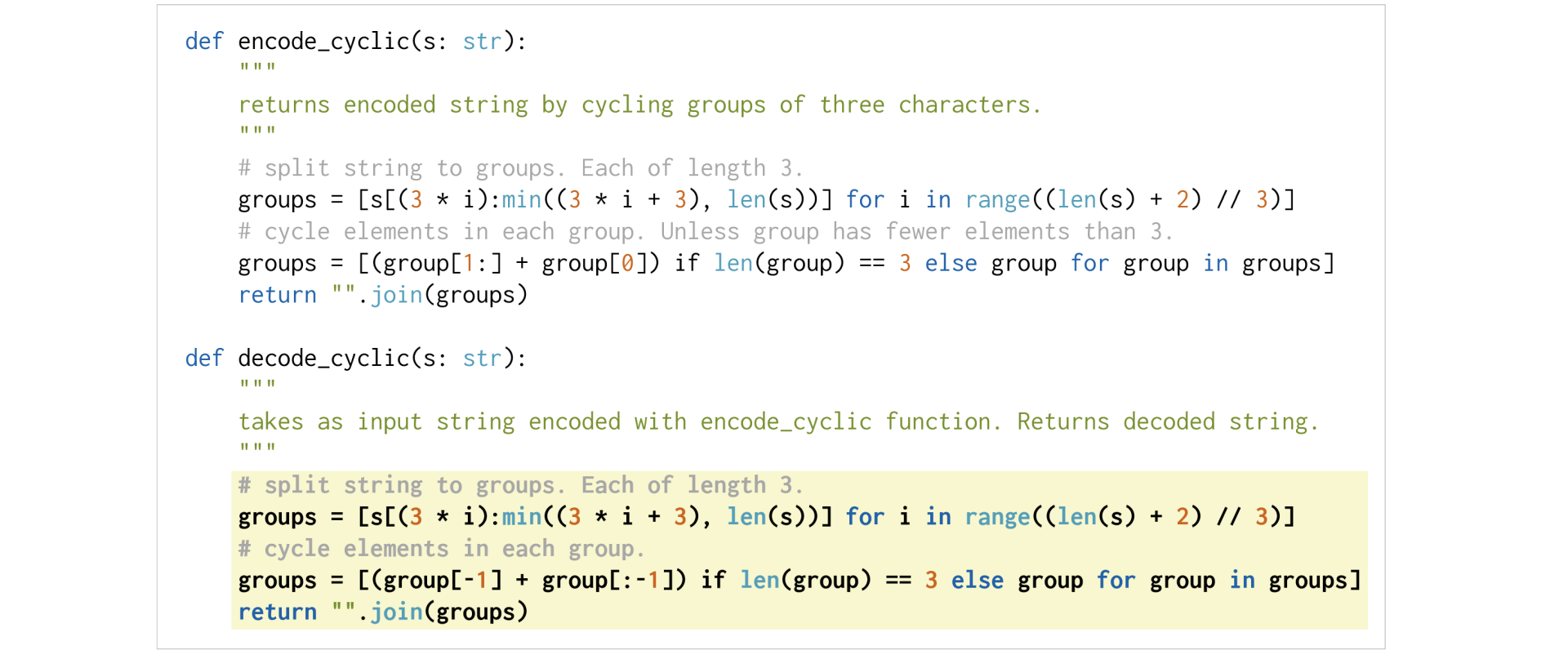

Fig 1. An example of Codex. ( The prompt provided to the model is shown with a white background, and a successful model-generated completion is shown in a yellow background. )

Future Efforts

Although large language models have made some progress in Human-AI Programming, there are still a number of limitations. Take Codex[18] as an example. First, such large language models are not sample efficient to train. Their training dataset comprises hundreds of millions of lines of code, even seasoned programmers may not encounter anywhere near this amount of code over their careers. But Codex still only solves easy-level problems, in that case, a junior student who completes an introductory computer science course is even expected to be able to easily beat Codex-12B[18]. Second, model performance degradation as docstring length increases, which means Codex struggles to parse through increasingly long and higher-level or system-level specifications. Third, Codex have difficulty with binding attributes to objects, especially when the number of operations and variables in the docstring is large. So back to our previous questions: 1). To what extent is there ongoing collaboration between human and the AI system? Apparently, it’s only limited collaboration at the moment based on the above limitations for Human-AI Programming. 2). Does the AI or human agent contribute more to the system’s decision-making/action-taking? Currently, human still dominate and contribute more to programming tasks. In the future, we expect AI models to address more complex, unseen problems that require true problem-solving skills beyond simply translating instructions into code so that achieving a higher degree of Human-AI Collaboration.

Human-AI Co-Creation

Involving the active use of imagination and innovation, creativity was once considered unique to human[21]. As the emergence of AI technologies, some researchers proposed a concept named “AI creativity”[22], which refers to the ability for human and AI to co-live and co-create by playing to each other’s strengths. In line with this concept, recent research work incorporated AI collaborators into human’s creation process, especially the process of artistic creation. For example, AI drummers were developed to collaborate with human musicians in musical improvisation and live performance[23]; DuetDraw provided an interface allowing users and AI agents to draw pictures collaboratively[24]; NLP models and human collaborated on creative writing tasks, such as short story writing[25].

Current Progress

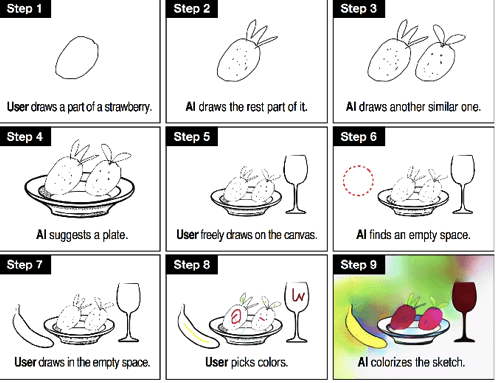

The goal of human-AI co-creation is not to replace human creativity or automate the creation process[24, 25]. Although closely collaborating with AI, human participants play the leading role in creation. In contrast, AI systems are designed as complements to human creativity[22], which could provide suggestions for next steps or complete some repetitive tasks in creation. For example, in collaborative story writing, AI suggests new writing ideas as a story unfolds[25]; when drawing pictures collaboratively, AI could automatically draw the same object that a user has just drawn in a slightly different form[24]. Results of user studies align with such a human-centered design: users prefer to take the initiative when collaborating with AI; major and creative tasks should be assigned to human while repetitive and arduous task should be assigned to AI[24].

Compared with human working alone, incorporating AI collaborators could improve both user performance and user experience in creation process:

-

AI could inspire human’s creativity, especially when human get stuck in creation process. For example, in DuetDraw[24], AI models could point out an empty space on the canvas, where user may further add new objects.

-

Human have various positive experiences through interaction with AI. When drawing pictures collaboratively, users are delighted to see the unexpected objects drawn by AI[24]. In collaborative story writing, users enjoyed writing with AI’s suggestions[25]. AI collaborators also allow users, especially less experienced writers, to write in a judgement-free setting without pressure from human collaborators[25].

Future Efforts

Although promising, human-AI co-creation is a new and developing area with challenging problems to solve. One of the outstanding problems faced by human-AI co-creation is the communication between human and AI during creation process. In group collaboration for artistic creation, human creators not only convey arts-related information to other creators, but also send and receive non-arts cues, such as body language and eye contact, from which creators could identify the intentions of their collaborators. However, when it comes to collaboration with a non-human creator, these important cues are missing in the creation process[23]. This could negatively influence the efficiency of collaboration and the trust built between human and AI in co-creation.

To improve the communication between human and AI, there are some future efforts to take:

- For the communication from human to AI, researchers need to take more “social cues” into consideration[26]. Future research work could borrow measurement methods from the area of psychology and cognitive science. After quantifying human participants’ emotion, attention, engagement, and intention, AI models could utilize these behavioral data to better learn about their human collaborators.

- For the communication from AI to human, including explanations and confidence into the conveyed information will help build trust in collaboration[22]. Moreover, the suggestions provided by AI collaborators need to keep a balance between coherence and novelty[25]: while novel and surprising suggestions could inspire human creators, they can be distracting and far away from the creation goal.

Besides improving communication, there are also other future directions of human-AI co-creation. Building general framework for human-AI collaboration in creative activities will simplify the development of related applications and facilitate the comparison of different research work. Meanwhile, it is also critical to thoughtfully design task-specific patterns in AI systems that accommodate different creation tasks. With continuous improvements, we believe “AI creativity” will bring tremendous inspirations to arts and science in the future.

Discussion

Comparing human-AI programming and human-AI co-creation, we noticed some similarities between the two generation tasks. Humans are in dominant positions for both of the tasks. AI could assist people in writing code or creating artwork, but it could not replace human programmers or human artists. Human participants also hope to take the leading role instead of simply following AI’s suggestions or actions.

The difference between the two generation tasks lies in the level of collaboration. For human-AI programming, there are limited collaborations between human and AI. The duty of AI is usually only to translate the natural language instructions into code. In contrast, human-AI co-creation involves close collaboration between human and AI creators. AI needs to give suggestions based on the current work at each step of the creative task. Although human takes the dominant part in both of the tasks, AI’s roles are slightly different: For human-AI programming, AI is usually viewed as a “coding assistant” that fulfills the requirement of human programmers; For human-AI co-creation, AI is regarded as a creator that provides recommendations and inspirations for human artists. We think this is mainly because code generation is a relatively new area, and current code generation methods are not as strong as image or text generation methods. Therefore, people tend to view AI as an assistant instead of a partner during coding.

The investigations on human-AI programming and human-AI co-creation provide us with insights into the future work of human-AI generation tasks, or even the larger area of “Human-AI Collaboration”:

- To achieve a higher level of collaboration, we need to strengthen AI’s ability on corresponding tasks. For example, code generation methods could be improved to solve more complex coding problems and process more complicated instructions from humans. Besides performance, interpretability and generalization ability are also equally important.

- Communication is the essential part of human-AI generation tasks. It is worth noticing that the communications in human-AI collaboration are bi-directional: Human conveys task-related information, intentions, emotions, and expectations to AI, while AI gives suggestions, confidence scores, and explanations to human. We need to take both directions into consideration when designing human-AI collaboration systems.

Conclusion

In this survey, we delved into two human-AI collaborated generation tasks: Human-AI Programming and Human-AI Co-Creation. In both of the tasks, human plays the dominant role, and AI could help human complete tasks or inspire human with new ideas. Our investigation shows that both “human factors” and “AI factors” are indispensable components in human-AI collaboration. Future work needs to work on the improvement of AI’s ability as well as the bi-directional communication between human and AI during collaboration.

Reference

[1] Thorsten Brants, Ashok C Popat, Peng Xu, Franz J Och, and Jeffrey Dean. Large language models in machine translation. 2007.

[2] Hangbo Bao, Li Dong, and Furu Wei. Beit: Bert pre-training of image transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08254, 2021.

[3] Alexei Baevski, Yuhao Zhou, Abdelrahman Mohamed, and Michael Auli. wav2vec 2.0: A framework for self-supervised learning of speech representations. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:12449–12460, 2020.

[4]AlexanderRives,JoshuaMeier,TomSercu,SiddharthGoyal,ZemingLin,JasonLiu,DemiGuo, Myle Ott, C Lawrence Zitnick, Jerry Ma, et al. Biological structure and function emerge from scaling unsupervised learning to 250 million protein sequences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(15), 2021.

[5] Rowan Zellers, Ximing Lu, Jack Hessel, Youngjae Yu, Jae Sung Park, Jize Cao, Ali Farhadi, and Yejin Choi. Merlot: Multimodal neural script knowledge models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 2021.

[6] Laria Reynolds and Kyle McDonell. Prompt programming for large language models: Beyond the few-shot paradigm. In Extended Abstracts of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–7, 2021.

[7] Leo Gao, Stella Biderman, Sid Black, Laurence Golding, Travis Hoppe, Charles Foster, Jason Phang, Horace He, Anish Thite, Noa Nabeshima, et al. The pile: An 800gb dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00027, 2020.

[8] Ben Wang and Aran Komatsuzaki. Gpt-j-6b: A 6 billion parameter autoregressive language model, 2021.

[9] Zohar Manna and Richard J Waldinger. Toward automatic program synthesis. Communications of the ACM, 14(3):151–165, 1971.

[10] Chris Maddison and Daniel Tarlow. Structured generative models of natural source code. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 649–657. PMLR, 2014.

[11] Miltos Allamanis, Daniel Tarlow, Andrew Gordon, and Yi Wei. Bimodal modelling of source code and natural language. In International conference on machine learning, pages 2123–2132. PMLR, 2015.

[12] Pengcheng Yin and Graham Neubig. A syntactic neural model for general-purpose code generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.01696, 2017.

[13] Uri Alon, Shaked Brody, Omer Levy, and Eran Yahav. code2seq: Generating sequences from structured representations of code. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.01400, 2018.

[14] Colin Raffel, Noam Shazeer, Adam Roberts, Katherine Lee, Sharan Narang, Michael Matena, Yanqi Zhou, Wei Li, and Peter J Liu. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.10683, 2019.

[15]TomBrown,BenjaminMann,NickRyder,MelanieSubbiah,JaredDKaplan,PrafullaDhariwal, Arvind Neelakantan, Pranav Shyam, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems, 33:1877–1901, 2020.

[16] Zhangyin Feng, Daya Guo, Duyu Tang, Nan Duan, Xiaocheng Feng, Ming Gong, Linjun Shou, Bing Qin, Ting Liu, Daxin Jiang, et al. Codebert: A pre-trained model for programming and natural languages. arXiv preprint arXiv:2002.08155, 2020.

[17] Colin Clement, Dawn Drain, Jonathan Timcheck, Alexey Svyatkovskiy, and Neel Sundaresan. PyMT5: multi-mode translation of natural language and python code with transformers. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 9052–9065, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[18] Mark Chen, Jerry Tworek, Heewoo Jun, Qiming Yuan, Henrique Ponde de Oliveira Pinto, Jared Kaplan, Harri Edwards, Yuri Burda, Nicholas Joseph, Greg Brockman, et al. Evaluating large language models trained on code. arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.03374, 2021.

[19] Yujia Li, David Choi, Junyoung Chung, Nate Kushman, Julian Schrittwieser, Rémi Leblond, Tom Eccles, James Keeling, Felix Gimeno, Agustin Dal Lago, et al. Competition-level code generation with alphacode. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.07814, 2022.

[20] Erik Nijkamp, Bo Pang, Hiroaki Hayashi, Lifu Tu, Huan Wang, Yingbo Zhou, Silvio Savarese, and Caiming Xiong. A conversational paradigm for program synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.13474, 2022.

[21] James C Kaufman and Robert J Sternberg. The Cambridge handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[22] Zhuohao Wu, Danwen Ji, Kaiwen Yu, Xianxu Zeng, Dingming Wu, and Mohammad Shidu- jaman. Ai creativity and the human-ai co-creation model. In International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, pages 171–190. Springer, 2021.

[23] Jon McCormack, Toby Gifford, Patrick Hutchings, Maria Teresa Llano Rodriguez, Matthew Yee-King, and Mark d’Inverno. In a silent way: Communication between ai and improvising musicians beyond sound. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, pages 1–11, 2019.

[24] Changhoon Oh, Jungwoo Song, Jinhan Choi, Seonghyeon Kim, Sungwoo Lee, and Bongwon Suh. I lead, you help but only with enough details: Understanding user experience of co-creation with artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pages 1–13, 2018.

[25] Elizabeth Clark, Anne Spencer Ross, Chenhao Tan, Yangfeng Ji, and Noah A Smith. Creative writing with a machine in the loop: Case studies on slogans and stories. In 23rd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, pages 329–340, 2018.