Module 1: A study of Human-AI Collaboration in Healthcare

In this report, we survey the impact of Human-AI Collaboration in the Healthcare setting. We categorise the various studies done in this domain on the basis of their major focus, be it model architecture, human trust or virtual assistance. For each category, we provide an analysis of varied work done in this sub-domain, identifying their key takeaways. The survey also provides a bigger picture on the current trends in human-AI collaboration in healthcare, answering some key questions on the role each stakeholder plays. In doing so, we also identify some key challenges in furthering development in this field, and conclude with our view on the future of Human-AI Collaboration in healthcare.

- Introduction

- Human-AI Collaboration in Healthcare

- Current Trends in Human-AI Collaboration in Healthcare

- Challenges and Vision for the Future

- Concluding Remarks

- References

Introduction

The domain of healthcare and medical research demonstrates a great need for human-AI collaboration. Tasks such as radiologist annotations and classifications that are repetitive and prone to human error show great scope for the use of AI tools in collaboration with human expert knowledge. In this paper, we present and assess the uses of human-AI collaboration in the domain of healthcare. In the next section, we survey the various subdomains in this field classified into three broad categories, architectural(AI focused), behavioral(human focused) and virtual assistance in healthcare. The architecture focused studies focus on the latest frameworks used in human-AI collaborations for particular medical tasks such as classification and prediction. The following section of behavioural studies will assess more about the value of the interaction and trust between human knowledge and artificial intelligence. The last section will talk about theoretical approaches and real-world applications in the domain of virtual assistance in healthcare.

Besides the domain study, we will extend the topic further with current trends of research and application in human-AI collaborated healthcare. Moreover, we will also assess the limitations of current achievements and give a comprehensive analysis of future trends in the fields based on the studies in previous sections

Human-AI Collaboration in Healthcare

Several studies have been conducted over the years in understanding the role of human-AI collabo- ration in healthcare. For the purpose of this paper, we categorise these studies on the basis of their underlying focus. In this regard, we classify the studies across three domains : architectural, behavioural and virtual assistance.

Architectural (AI Focused) Studies

In this section, we describe the works that focus on developing new models, architectures or other computing components with a goal to improve some metric such as accuracy or dice score over current state of the art. The last few years have seen several works that attempt to utilise human knowledge in improving AI systems in healthcare, with a goal towards beating the performance of pure AI or pure human solutions.

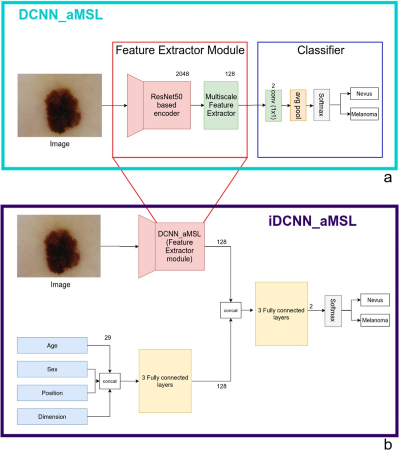

An initial foray into this domain reveals works that seek to improve prediction power for a particular medical task. The iDCNN-aMSL model[1] is one such recent work that leverages human-AI collaboration to discriminate between atypical nevi (AN) and early melanoma (EM) in skin-cancer diagnosis. The authors of this work first presented a deep convolution model architecture, DCNN-aMSL , trained exclusively on these difficult cases. The architecture of this model (see figure 1) derives from a modified version of the Segmentation Multiscale Attention Network[2] , due to its proven success in medical image analysis. It comprised of two main modules: a feature extractor module based off a modified ResNet50[3] architecture to extract relevant high-level features from a dermsocopic input, and a classifier module that leveraged a convolutional layer with separate feature maps for AN and EM.

Leveraging this convolutional model, the authors then developed an integrated architecture, i.e, iDCNN-aMSL, that took into account both images and relevant clinical data such as age and gender (see figure 1). The goal was to empower a model that can make predictions using all the available information that a medical practitioner would have. The model had a 3-modular architecture, with the feature extractor performing the previously discussed task of feature extraction from the image, and a 3-layer fully connected network performing feature extraction from the clinical data. A final fully connected block took in a concatenated representation of both features (at a total of 29), and fed it to a softmax layer for the final prediction. The model was tested on a test dataset bearing 214 samples, and demonstrated an AUC of 90.3% , beating the DCNN-aMSL model which gave an AUC of 86.6%. Additionally, both these models boasted a better performance than that of a dermatologist.

Fig 1. a).The DCNN-aMSL model b).The iDCNN-aMSL with the three-modular structure[1]

Along similar lines as [1], the IDSP (Interpretable Weighted Deep Signaling Pathways)[4] architecture used a deep graph neural network architecture to improve synergic drug combination prediction, by incorporating gene-gene and gene-drug regulatory relationships. The model leveraged a multi-layer perceptron(MLP)[5] with an attention-based approach and neighbourhood aggregation[6]. The authors demonstrate that when validated on drug combinations from the NCI Almanac [7], the model achieved state-of-the-art performance on transductive prediction tasks. The model also demonstrated comparable performance against models like DeepSynergy[8] despite not using any drug chemical features. Additionally, when compared with DeepSignallingSynergy[9], which takes the same input as IDSP, the latter demonstrates more potential in being used in a real-world setting on account of producing more interpretable results for module interaction.

The above two works target improving prediction power by allowing more information to be learned by the model to facilitate better predictions. A second line of work in this domain involves tools that work with user-interaction to improve and provide optimal results. This is highlighted by the SMILY model [10] (Similar Medical Image Like Yours). The authors of this work present an interactive tool to facilitate better Content Based Image Retrieval (CBIR)[11] with the help of user refinement. The work is set in the domain of differential diagnosis, in order to help medical practitioners differentiate a disease from others that share similar clinical features. The architecture involves feeding the query image through a pre-trained DNN to retrieve its image embedding, and thus obtain simliar images via a nearest-neighbour approach.

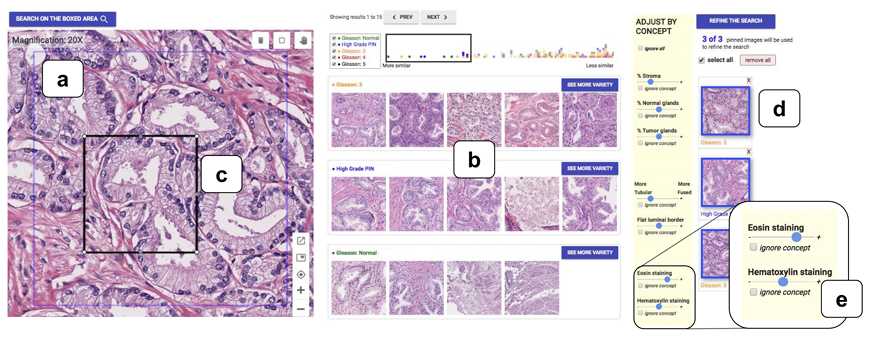

Fig 2. The SMILY component overview a).Query Image b). Search Results c). Refine-by-region tool d). Refine-by-example-tool e). Refine-by-concept-tool[10]

The paper also proposes three unique refinement approaches to allow medical practitioners to improve the CBIR results (see figure 2). The first, "refine by region", allows region cropping to isolate important features. The second, "refine by example", allowed users to specify a subset of the initial search results as model examples, and thus find more such examples. The final refinement tool, "refine by concept", allowed end-users to indicate their preference on how much of a particular medical concept should appear in the search results. Of the three techniques, the "refine-by-concept" technique demonstrated the most promise, with experimental results showing a greater relevant concept presence in almost every case(99%).

The papers surveyed in this section thus demonstrate the various studies that have sought to improve the utility of AI models in healthcare. While works such as [1] and [4] seek to directly improve prediction power through architectural improvements and information collection, works such as [10] and other feedback based tools such as [12] consider a more interaction-centric approach, focusing on serving as a utility tool.

Behavioural (Human Focused) Studies

In this section, the focus shifts from AI models and prediction power, to a discussion on the humans involved. Several studies have been conducted over the years that raise key questions on the settings under which AI is usable in healthcare and the people who are likely to benefit from the usage of AI. A key consideration in all these discussions is the aspect of trust,i.e, what makes a trustworthy AI model, and to what extent should AI be trusted in healthcare.

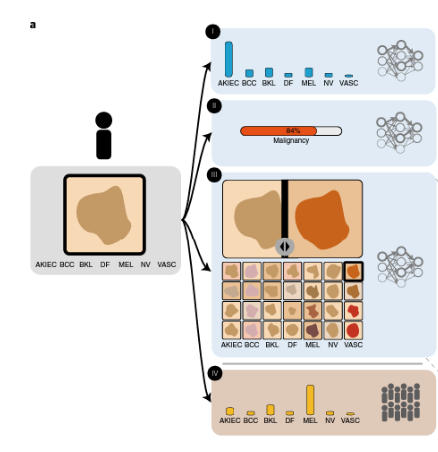

One key work that explores quite comprehensively the "human" aspect of Human-AI collaboration is a study on human-computer collaboration in skin-cancer recognition[13]. It studies the various factors that motivate human-AI collaboration for this multi-class classification problem, and attempts to motivate a shift from competition to collaboration. The first key finding that this paper demonstrates is the importance of choosing the right AI representation for decision support, based on the task at hand (see figure 3). The authors demonstrate that for the problem of skin-cancer classification, AI-based multi class probabilities were the most suitable representation, improving accuracy from 63% to 77%, while other representations such as CBIR[11] showed no improvement on the task. Secondly, the paper sought to analyse which people benefited the most from using AI. Through multiple experiments, the authors demonstrated an inverse relationship between the net gain from AI-based support and rater experience.

Another key finding of this study was the impact of interpretable AI, where the use of methods such as GradCAM[14] in the particular case of classifying pigmented actinic keratoses(AKE) demonstrated a key nuance on focusing on the background of the lesion. Experimental results demonstrated an increase in human classification accuracy when armed with this knowledge, with classification success on AKE jumping from 32.5% to 47.3%. Finally, the paper also sought to demonstrate the catastrophic effects that blind trust in an AI system could have, as experimental results demonstrated that using a faulty AI resulted in significant performance dips for all users. This point is also corroborated by a study that focuses on the clinicians in this human-AI collaborative setting [15], in which an "optimal trust" level is described. Under this optimal trust, both the human and the AI system maintain some skepticism about each other’s diagnoses. This ensures that neither relies blindly on the other’s decision, which could otherwise be catastrophic when either system makes a mistake.

Fig 3. Human AI interactions with different forms of support a). Multiclass probablity b). Malignancy probability c).CBIR d). Crowd-based Multiclass probability[13]

Other works in the domain focus more exclusively on the various factors around trust. The paper entitled Do as AI say[16] conducted a study to determine the impact of advice on the performance of expert radiologists and non-expert physicians on a particular clinical task. The study created accurate and inaccurate advice, and artificially marked some of them as human provided and others as AI provided. It demonstrated that most participants were able to successfully rate inaccurate advice as lower quality, and that these ratings were largely source independent. A key finding however, was that unlike previous studies , participants were not averse to utilising algorithmic advice in making their decision, with a general tendency to agree with the advice. This yet again underlines the concern of decisions arriving from a faulty AI, which could have catastrophic effects when physicians are unable to filter out inaccurate advice.

Another study involved defining what "trust" meant in the AI healthcare setting [17]. The paper gauged the importance of doctor-patient trust in the healthcare setting, built by an implicit recognition of the doctor’s experience, and fostered through repeated interactions. It argued that in order for an AI system to be effective in a healthcare system, it’s role must be clearly defined. A patient is more likely to trust an AI system that has some sort of licensure on its expertise, similar to that of a doctor. A key factor in this involves the interpretabiliity and explainability of the system, as opposed to a black box who’s expertise a patient cannot easily gauge, findings further supported through experimental results as in [13].

As a whole, the papers in this section demonstrated a line of study that focus on the "human" aspects of human-AI collaboration. While works such as [13] quantified experimental results to demonstrate when and how humans benefit from AI, works such as [16],[17] sought to foster discussion on what it takes to build a trustworthy AI system, underlining the critical importance of trust in the healthcare setting.

Virtual Assistance

Virtual assistance is an evolving and hot topic in human centered artificial intelligence. Many successful research works have been published and used in many fields of industry. In this section, we first introduce three representative theoretical approaches with different frameworks in virtual assistance. Then, we focus on how the academic accomplishments are transferred into applications in the healthcare area. Among the three approaches, the first one is the retrieval-based method, which searches from a candidate pool for a best match, while the second generation method generates responses from scratch or given inputs.The last one is the hybrid method of the previous two.

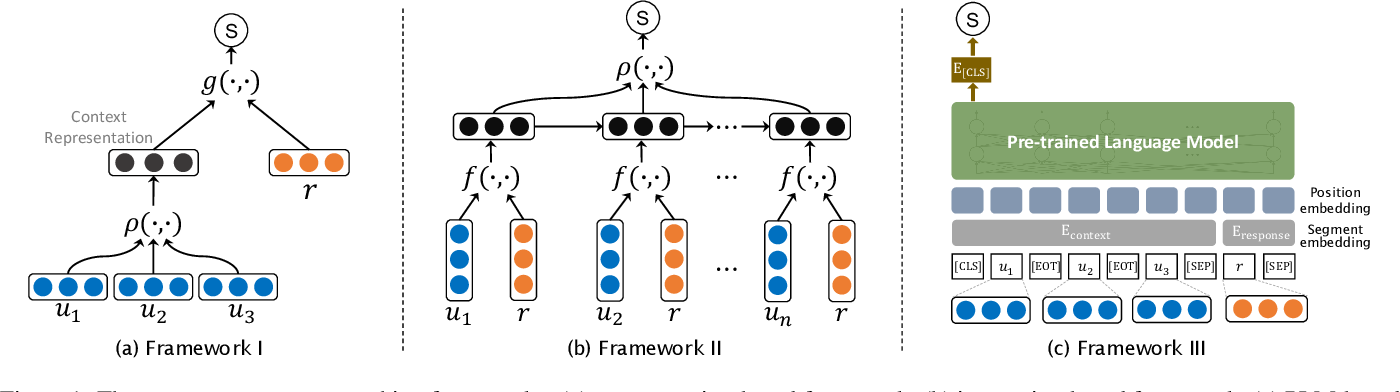

Retrieval-based methods assume that the response comes from a pool of candidate responses, which are all existing human responses. This method generally evaluates the score of each possible candidate, and gives out the answer with the highest score. Among all retrieval-based methods, representation-based models, interaction-based models and PLM-based models are the most popular frameworks[18] (see figure 4). On the other hand, a generation-based method synthesizes responses word by word, and thus can produce new answers outside of existing ones. Most existing generation-based methods are based on encoder-decoder architectures.The end to end nature of this architecture directly sends the inputs into an embedding of the contextual information. And the decoder then automatically picks a new word and the next hidden state.

From experiments and research results, retrieval-based methods usually produce high quality, fluent and grammatical results contributing to the mature candidate pool of real conversations. However, the hypothesis space of retrieval-based approach is limited and weighs too much in the results generation. Generation-based methods,risking the guarantee of receiving high quality results, benefit from larger search spaces and the possibility to produce unseen responses outside of training data. Therefore, the approach that combines the strengths of the two fashions has dominated virtual assistance research recently. They usually consist of two stages, where in the first stage, many similar conversation candidates are retrieved from the dataset, and in the second stage, the retrieved instances are used and enhanced in various ways to assist the generator generating better responses [19].

Fig 4. Three context-response matching frameworks: (a) representation-based framework; (b) interaction-based framework; (c) PLM-based framework[18]

Artificial intelligence based virtual assistance has many applications in healthcare. They are mostly information retrieval based methods, which in practice provides a more reliable service. During COVID-19 pandemic, AI-based chatbots played an important role of extracting and collecting information, matching patients and physicians, and assisting diagnosis. Healthily, for example, is an app with AI-based virtual assistance that provides patients information about diseases’ symptoms and health assessments. In addition, chatbots like Woebot[20] provide mental health assistance that deliver cognitive behavioral therapy for patients, which also relieved the exploding demands for psychological healthcare during the pandemic. [21]

Current Trends in Human-AI Collaboration in Healthcare

The above section helps contextualise the current state of human-AI involvement in the healthcare domain. It discusses the various approaches that have been taken towards understanding and developing effective AI in this domain, whilst balancing the role of the various human stakeholders in this domain, i.e, doctors, lab clinicians and the patients. In this section , we thus discuss two key questions to underline the current state of human-AI collaboration in healthcare. These questions are based off a study conducted on Human-AI collaboration [22].

The first question asks about the extent of ongoing collaboration between AI systems and the humans. This can be answered from two different standpoints. From evolving studies such as [8],[9],[4], as well as continuous levels of development , such as in [1], one can conclude that the current ongoing collaboration between AI systems and developers is quite active, as this is an active area of research. A caveat however is that this collaboration ceases the moment the model requires to be tested in clinical settings, as models are often frozen before clinical trials. From a user-AI collaboration standpoint however, the current collaboration is quite limited. The domain of healthcare requires exceptional accuracy and precision, and current AI systems are not yet at the mark to be applied directly into clinical settings. However, recent developments and trends show promise towards a more active collaboration between AI and patients in the future. Realising this collaboration however, requires a careful balance of doctor- AI, patient-AI and doctor-patient trust, as well as clearly defined roles for all the stakeholders involved.

The second question builds off of the first one, asking on which player contributes more towards decision making, the AI or the user. Current studies such as in [1],[10],[12] demonstrate that AI currently plays a supportive role, aiding in the process of decision-making by providing prediction probabilities or supporting results. The final decision making power however, still rests in the hands of the medical professionals, who take the important calls on diagnosis and required medical procedures. Given the significant impact that a single medical decision can have on a person’s life, allowing AI to play supporting roles that can aid and support a medical professional in making the right decision seems to be the most promising way forward. It allows the medical professionals to act faster through the aid of AI, whilst also incorporating their professional experience in validating and if necessary overruling AI decisions.

Challenges and Vision for the Future

The dream of visualising AI support in healthcare seems promising. However, realising this dream requires overcoming several challenges [23] . The first, and perhaps the most straightforward, involves developing more robust and accurate AI systems. Accuracy and correctness in a healthcare setting is paramount, as even a single mistake could be fatal. Therefore, building AI systems with near 100% accuracy remains a primary task. Another major challenge involves the question of trust. Successful deployment of any AI system in a healthcare setting would involve a clear definition of the role an AI system would play, without undermining the role of the doctor, or the trust between patient and doctor. For the smooth deployment of AI in everyday healthcare, patients would need a sense of guarantee in the accuracy and fairness of these systems, which can only be achieved through demonstrated performance. This in turn brings us to our last challenge, which involves the necessary but time-consuming process of clinical validation. These trials can take months and sometimes even years, and serve as a key bottleneck in successfully making AI systems clinically available. Thus, a key challenge in the development process would involve developing models with rigorous testing for robustness and correctness, to ensure a smooth passage through clinical validation.

In spite of these challenges however, the future of human-AI collaboration looks promising. As discussed in the last section, AI is showing more and more promise in serving as a supporting tool, that can help overcome human error and aid in the decision making process. These helps builds an optimistic sense towards AI taking over the more monotonous and repetitive tasks such as annotations and initial screenings, allowing medical professionals to focus their expertise on using the information provided to provide a final diagnosis. This would help ensure accurate, as well as faster care for patients, and a more promising future for healthcare in general.

Concluding Remarks

Trends and studies over the years have shown that human-AI collaboration has demonstrated solid results and incredible applications across several domains in the real world. This survey seeks to shed some light on the utility of this collaboration in healthcare. Through an analysis of studies across various contexts such as architectural, behavioural and virtual assistance, we observe promising results, as well as identify potential for further improvement with the development of the architectures and frameworks.

References

[1] Linda Tognetti, Simone Bonechi, Paolo Andreini, Monica Bianchini, Franco Scarselli, Gabriele Cevenini, Elvira Moscarella, Francesca Farnetani, Caterina Longo, Aimilios Lallas, Cristina Carrera, Susana Puig, Danica Tiodorovic, Jean Luc Perrot, Giovanni Pellacani, Giuseppe Argenziano, Elisa Cinotti, Gennaro Cataldo, Alberto Balistreri, Alessandro Mecocci, Marco Gori, Pietro Rubegni, and Alessandra Cartocci. A new deep learning approach integrated with clinical data for the dermoscopic differentiation of early melanomas from atypical nevi. Journal of Dermatological Science, 101(2):115–122, 2021.

[2] Simone Bonechi, Monica Bianchini, Franco Scarselli, and Paolo Andreini. Weak supervision for generating pixel–level annotations in scene text segmentation. Pattern Recognition Letters, 138:1–7, 2020

[3] Kaiming He, Xiangyu Zhang, Shaoqing Ren, and Jian Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pages 770–778, 2016.

[4] Zehao Dong, Heming Zhang, Yixin Chen, and Fuhai Li. Interpretable drug synergy prediction with graph neural networks for human-ai collaboration in healthcare. CoRR, abs/2105.07082, 2021.

[5] Marius-Constantin Popescu, Valentina Balas, Liliana Perescu-Popescu, and Nikos Mastorakis. Multilayer perceptron and neural networks. WSEAS Transactions on Circuits and Systems, 8, 07 2009.

[6] Gabriele Corso, Luca Cavalleri, Dominique Beaini, Pietro Liò, and Petar Veliˇckovi ́c. Principal neighbourhood aggregation for graph nets. In H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M.F. Balcan, and H. Lin, editors, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, volume 33, pages 13260–13271. Curran Associates, Inc., 2020.

[7] Holbeck, S. L., Camalier, R., Crowell, J. A., Govindharajulu, J. P., Hollingshead, M., Anderson, L. W., Polley, E., Rubinstein, L., Srivastava, A., Wilsker, D., Collins, J. M., & Doroshow, J. H. (2017). The National Cancer Institute ALMANAC: A Comprehensive Screening Resource for the Detection of Anticancer Drug Pairs with Enhanced Therapeutic Activity. Cancer research, 77(13), 3564–3576. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0489

[8] Kristina Preuer, Richard P I Lewis, Sepp Hochreiter, Andreas Bender, Krishna C Bulusu, and Günter Klambauer. DeepSynergy: predicting anti-cancer drug synergy with Deep Learning. Bioinformatics, 34(9):1538–1546, 12 2017.

[9]Zhang H, Feng J, Zeng A, Payne P, Li F. Predicting Tumor Cell Response to Synergistic Drug Combinations Using a Novel Simplified Deep Learning Model. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2021;2020:1364-1372. Published 2021 Jan 25.

[10] Carrie J. Cai, Emily Reif, Narayan Hegde, Jason Hipp, Been Kim, Daniel Smilkov, Martin Wattenberg, Fernanda Viegas, Greg S. Corrado, Martin C. Stumpe, and Michael Terry. Human- centered tools for coping with imperfect algorithms during medical decision-making. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’19, page 1–14, New York, NY, USA, 2019. Association for Computing Machinery.

[11]Akgül CB, Rubin DL, Napel S, Beaulieu CF, Greenspan H, Acar B. Content-based image retrieval in radiology: current status and future directions. J Digit Imaging. 2011;24(2):208-222. doi:10.1007/s10278-010-9290-9

[12] Min Hun Lee, Daniel P. Siewiorek, Asim Smailagic, Alexandre Bernardino, and Sergi Bermúdez i Badia. A human-ai collaborative approach for clinical decision making on re- habilitation assessment. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, CHI ’21, New York, NY, USA, 2021. Association for Computing Machin- ery.

[13]Tschandl, P., Rinner, C., Apalla, Z. et al. Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat Med 26, 1229–1234 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0942-0

[14] Ramprasaath R. Selvaraju, Michael Cogswell, Abhishek Das, Ramakrishna Vedantam, Devi Parikh, and Dhruv Batra. Grad-cam: Visual explanations from deep networks via gradient- based localization. In 2017 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), pages 618–626, 2017.

[15] Onur Asan, Alparslan Emrah Bayrak, and Avishek Choudhury. Artificial intelligence and human trust in healthcare: Focus on clinicians. J Med Internet Res, 22(6):e15154, Jun 2020.

[16]Gaube, S., Suresh, H., Raue, M. et al. Do as AI say: susceptibility in deployment of clinical decision-aids. npj Digit. Med. 4, 31 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-021-00385-9

[17] Emily LaRosa and David Danks. Impacts on trust of healthcare ai. In Proceedings of the 2018 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society, AIES ’18, page 210–215, New York, NY, USA, 2018. Association for Computing Machinery.

[18]Chongyang Tao, Jiazhan Feng, Rui Yan, Wei Wu, and Daxin Jiang. A survey on response selection for retrieval-based dialogues. In Zhi-Hua Zhou, editor, Proceedings of the Thir- tieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21, pages 4619–4626. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 8 2021. Survey Track.

[19] Liu Yang, Junjie Hu, Minghui Qiu, Chen Qu, Jianfeng Gao, W. Bruce Croft, Xiaodong Liu, Yelong Shen, and Jingjing Liu. A hybrid retrieval-generation neural conversation model. CoRR, abs/1904.09068, 2019.

[20]Fitzpatrick K, Darcy A, Vierhile M Delivering Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Young Adults With Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Using a Fully Automated Conversational Agent (Woebot): A Randomized Controlled Trial JMIR Ment Health 2017;4(2):e19 URL: https://mental.jmir.org/2017/2/e19 DOI: 10.2196/mental.7785

[21] Lekha Athota, Vinod Shukla, Nitin Pandey, and Ajay Rana. Chatbot for healthcare system using artificial intelligence. pages 619–622, 06 2020.

[22]PAI Staff,"Human-AI Collaboration Framework & Case Studies",Partnership on AI, Collaborations Between People and AI Systems (CPAIS), 25 Sep 2019, "https://partnershiponai.org/paper/human-ai-collaboration-framework-case-studies/"

[23] Sun Young Park, Pei-Yi Kuo, Andrea Barbarin, Elizabeth Kaziunas, Astrid Chow, Karandeep Singh, Lauren Wilcox, and Walter S. Lasecki. Identifying challenges and opportunities in human-ai collaboration in healthcare. In Conference Companion Publication of the 2019 on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, CSCW ’19, page 506–510, New York, NY, USA, 2019. Association for Computing Machinery