Zero Shot Learning

Zero-Shot Learning (ZSL) enables models to classify unseen classes, which addresses scaleability challenges in traditional supervised learning. that requires extensive labeled data. By leveraging auxiliary information like semantic attributes, ZSL facilitates knowledge transfer to new, dynamic tasks. ZSL facilitates knowledge transfer to new, dynamic tasks. OpenAI’s CLIP exemplifies ZSL, aligning image and text embeddings though contrastive learning for flexible classification. In this study, we explore optimizing CLIP’s pre-trained model using prompt engineering. By testing various prompt formulations, from from generic (“A photo of a {}”) to highly specific (“A hand showing a [rock/paper/scissors]”), we aim to enhance classification accuracy, demonstrating ZSL’s potential for scalable and adaptable vision model.

- Zero-Shot Learning Introduction

- How does Zero-Shot Learning Work?

- Zero-Shot Learning Literature Discussion

- Running the CLIP Model

- Implementing our Own Ideas

- References

Zero-Shot Learning Introduction

Our project aims to present a comprehensive report of zero-shot learning by detailing its internal structure alongside providing both run results and custom experimentation results with the CLIP model.

Supervised learning machine learning models are extremely popular in the machine learning domain for their ability to leverage labeled data during training to make accurate predictions on unseen data. While these models perform well, one significant pain point with these models are their need for labeled data, which are costly to construct and limited in quantity. Moreover, even when trained on large amounts of labeled data, supervised learning models are limited to the numbers of classes already present in the data and can’t scale to new classes. These issues are so prevalent that an entire industry arose to develop high quality labeled datasets for machine learning models (ex. ScaleAI).

Zero-shot learning’s ability to label unlabeled data allows models to perform classification with unseen classes which directly addresses the pain points mentioned above. Zero-shot learning’s semantic space provides a lot of flexibility when labeling unseen data — in fact, it enables scalable classification when the number of unique classes grow. This has huge applicability, because it ultimately enables flexible model use in unseen environments. For instance, zero-shot learning can significantly help classifying rare diseases, categorizing products for a market, detecting cybersecurity anomalies, and adapting robots to new settings.

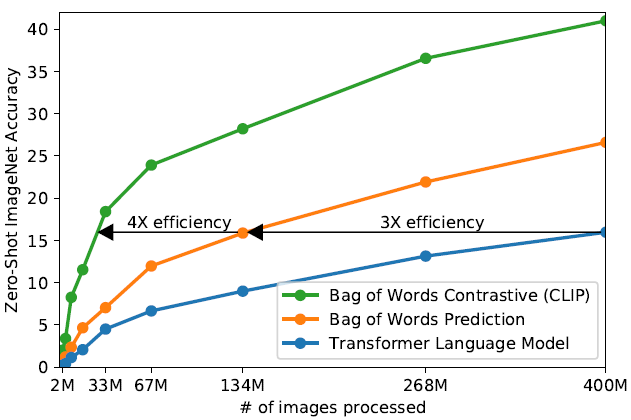

Figure 1: An image of the zero-shot ImageNet accuracy of various models (OpenAI, 2021)

In this report, we leverage OpenAI’s CLIP model to demonstrate zero-shot learning. At its core, the CLIP model is an image encoder and text encoder that was trained on 400 million image-text pairs to develop a complex semantic space. We run OpenAI’s existing CLIP codebase (https://github.com/openai/CLIP.git) and also implement our own ideas, showcased by prompt fine-tuning experimentation.

How does Zero-Shot Learning Work?

In order to achieve zero-shot classification, we need to pretrain the model in some semantic space that the seen dataset and the future unseen dataset both share. This semantic space is a high level representation of images and text where images and texts with similar meaning get mapped closer together. This space generalizes the representations of both visual and written data. The goal is that the semantic space generalizes well enough to be able to properly correlate unseen class labels with images.

# image_encoder - ResNet or Vision Transformer

# text_encoder - CBOW or Text Transformer

# I[n, h, w, c] - minibatch of aligned images

# T[n, l] - minibatch of aligned texts

# W_i[d_i, d_e] - learned proj of image to embed

# W_t[d_t, d_e] - learned proj of text to embed

# t - learned temperature parameter

# extract feature representations of each modality

I_f = image_encoder(I) #[n, d_i]

T_f = text_encoder(T) #[n, d_t]

# joint multimodal embedding [n, d_e]

I_e = l2_normalize(np.dot(I_f, W_i), axis=1)

T_e = l2_normalize(np.dot(T_f, W_t), axis=1)

# scaled pairwise cosine similarities [n, n]

logits = np.dot(I_e, T_e.T) * np.exp(t)

# symmetric loss function

labels = np.arange(n)

loss_i = cross_entropy_loss(logits, labels, axis=0)

loss_t = cross_entropy_loss(logits, labels, axis=1)

loss = (loss_i + loss_t)/2

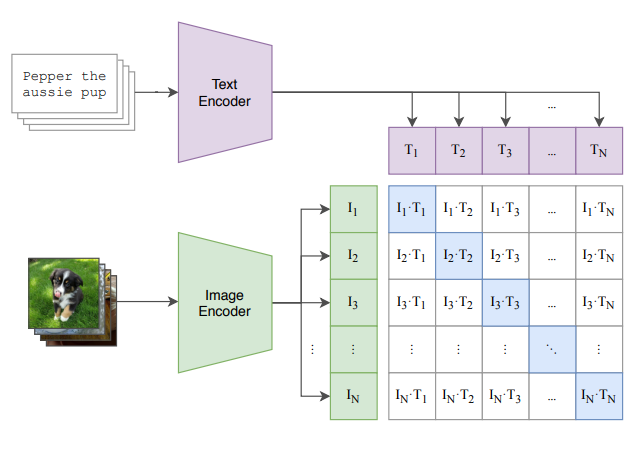

The pretraining process involves minimizing the Contrastive Loss Function (CLIP Loss). This is a loss function which computes the cosine similarity between the respective images and texts. During pre-training, we are given pairs of (image,text) data. A very important fact is that the texts must be a very detailed caption of the image. For example, instead of “dog”, the description would be “A photo of a brown coated dog jumping as it fetches a stick”. We can also vary the phrasing to not include “dog”, such as “A small, domestic, furry animal lying on a sofa”. This allows the model to interpret a wider range of semantic data.

We then take cross-entropy loss for each image to all texts and each text to all images. The goal is to maximize the similarity between the correct image-text pairs and minimize the incorrect pairings (along the diagonal).

Figure 3: An image of the pretraining process of the CLIP architecture. (Radford et al., 2021, Figure 1)

What’s left for pretraining is how we obtain the “encodings” for the texts and the images. These are just the embedding-spaces of certain models. For text-encodings, we can extract the encodings from a classical transformer model. For image-encodings, we can either crop (remove the final fc-layers) of a ResNet model or use a VisionTransformer (ViT). When we backpropagate through CLIP Loss, the weights of these encoders are what’s being trained.

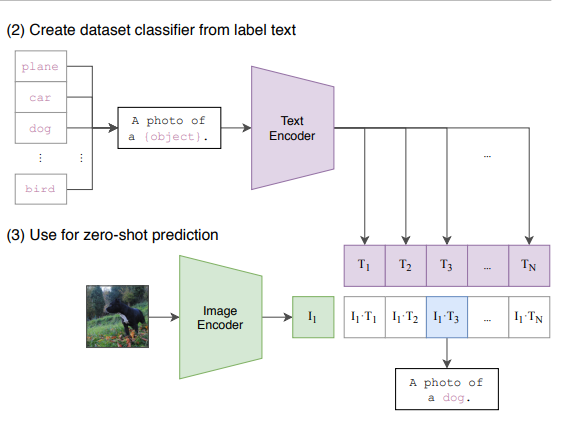

Figure 4: An image of the zero-shot classification process of the CLIP architecture. (Radford et al., 2021, Figure 1)

All that’s left is the classification part! Now, given some unseen class labels and images, which can be taken from an arbitrary dataset. We can keep the class label, or modify the text to fit a certain format, such as: “A photo of {label}”. This has a significant effect on the accuracy of the predictions which we discuss more below. Once the label is done, we can pipeline the images and our modified class labels into the encoders, then compute the cosine similarity between the text and image encodings. Take a softmax, then an argmax, and finally we have classified an image without ever looking at the new dataset!

Zero-Shot Learning Literature Discussion

Literature 1: Zero-Shot Learning with Semantic Output Codes

Published as a part of NIPS 2009 by Palatucci, et. al., this paper first formalized ZSL. Although there were a couple papers that previously touched on the topic, this paper was the first to focus primarily on ZSL. Simply put, the paper summarizes that:

“We consider the problem of zero-shot learning, where the goal is to learn a classifier \(f : X \to Y\) that must predict novel values of \(Y\) that were omitted from the training set” (Palatucci, et. al.)

Overall, the authors use semantic output codes to represent some intermediate state between the input features and the actual class labels. These are basically descriptions of the classes themselves by looking at key features that make a class unique from other classes. Therefore, this can be used to recognize new classes without ever being trained on those classes, as the model is simply predicting those intermediate states, known as the semantic output codes.

To support this process, there are two datasets that are needed: the actual input dataset and a “semantic knowledge base,” used to map the semantic output codes to actual classes. Therefore, although it is not necessary to have any training data for a class, the class must exist in the semantic knowledge base.

As this is one of the first papers in its topic, the paper formalizes the theory behind ZSL and proves why the model could work. The authors then show an example by training a ZSL model on an fMRI dataset. They showed that they could predict classes that were never seen in the training dataset so long as there existed data in the semantic knowledge base.

This work set the foundation for others to develop zero-shot learning techniques. As we build larger and larger classifiers, being able to use less labeled data would enable the deep learning community to develop new and larger models faster.

Literature 2: Feature Generating Networks for Zero-Shot Learning

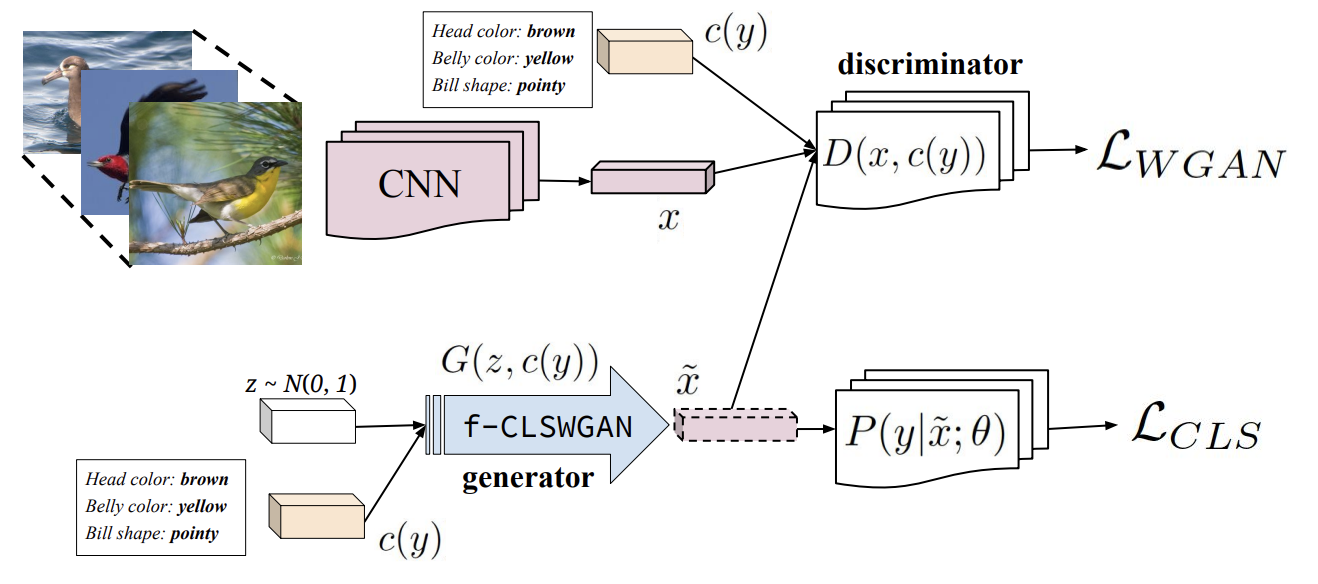

This paper, published in CVPR, introduces ZSL for generative models. Specifically, the paper uses ZSL in Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to generate an image in a class using only the semantic description of the class as opposed to any labelled training data.

At the core of their methodology is a feature generator. This is a neural network that takes a class embedding (the semantic description) and random gaussian noise. The generator produces a set of image features that matches the semantic description. Along with the generator is a discriminator, which attempts to distinguish the output of the generator as real or fake. Although this is the normal way to create a GAN, this zero-shot learning approach comes with a major change — the input to both the generator and the discriminator is conditioned on a set of features.

Figure 5: An image of the proposed model architecture that leverages synthesized CNN features for a novel GAN (Xian, et. al., 2018)

Therefore, we have an approach where a generator is provided Gaussian noise along with a vector \(c(y)\) that contains the semantic embedding of the requested output class. The generator outputs an image and the discriminator, also provided \(c(y)\), determines if the image is real or fake.

This model was tested on a dataset of animals with attributes and showed that their approach was significantly better than previous ZSL methods. This paper has enabled further research opportunities in ZSL for generative models. Because generative models have less labeled data by nature of their prompts being open ended, ZSL has provided improved performance in this space.

Literature 3: Learning a Deep Embedding Model for Zero-Shot Learning

Published in CVPR, this paper states that deep zero-shot learning (ZSL) models are not popular due to the fact that deep ZSL models have very few advantages over non-deep ZSL models with deep feature representation. However, the authors argue that deep ZSL models can have better performance than the alternative variations if a visual space is utilized as an embedding space rather than the common semantic and intermediate space. They emphasize that the most important factor for a successful deep ZSL model is the embedding space itself and leveraging methods like end-to-end optimization which can lead to a higher performing embedding space.

Their proposed deep embedding network for the ZSL utilizes two methods: applying a multi-modality fusion method and using the output visual feature space of a CNN subnet as the embedding space. This approach is able to reduce the hubness problem, which is a problem that affects ZSL models when they get too biased for particular labels.

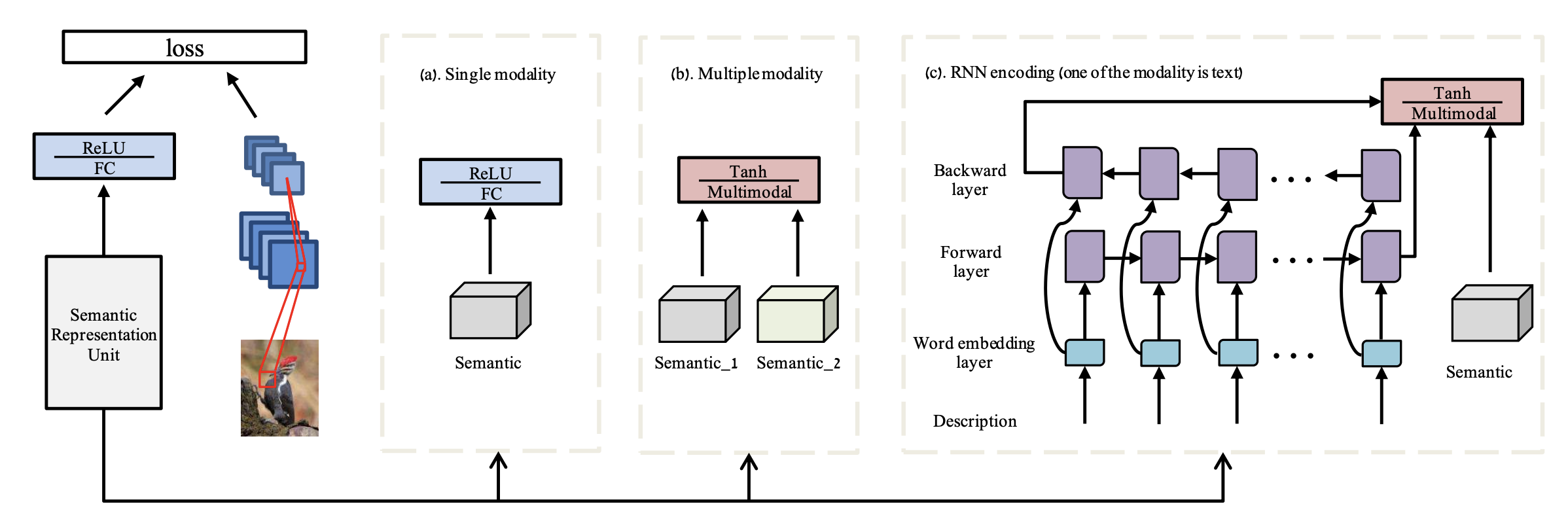

Figure 6: An image of the architecture for the proposed deep embedding model (Zhang, et. al., 2017)

As figure 6 demonstrates, the authors’ proposed model has a visual encoding branch which has a CNN subnet that receives an input image and outputs a D-dimensional feature vector; this feature vector acts as the embedding space. This specific encoding branch is considered one semantic representation unit. Depending on whether the model design has single modality, multiple modality, or RNN encoding, the authors provide recommended model design approaches as shown in the figure.

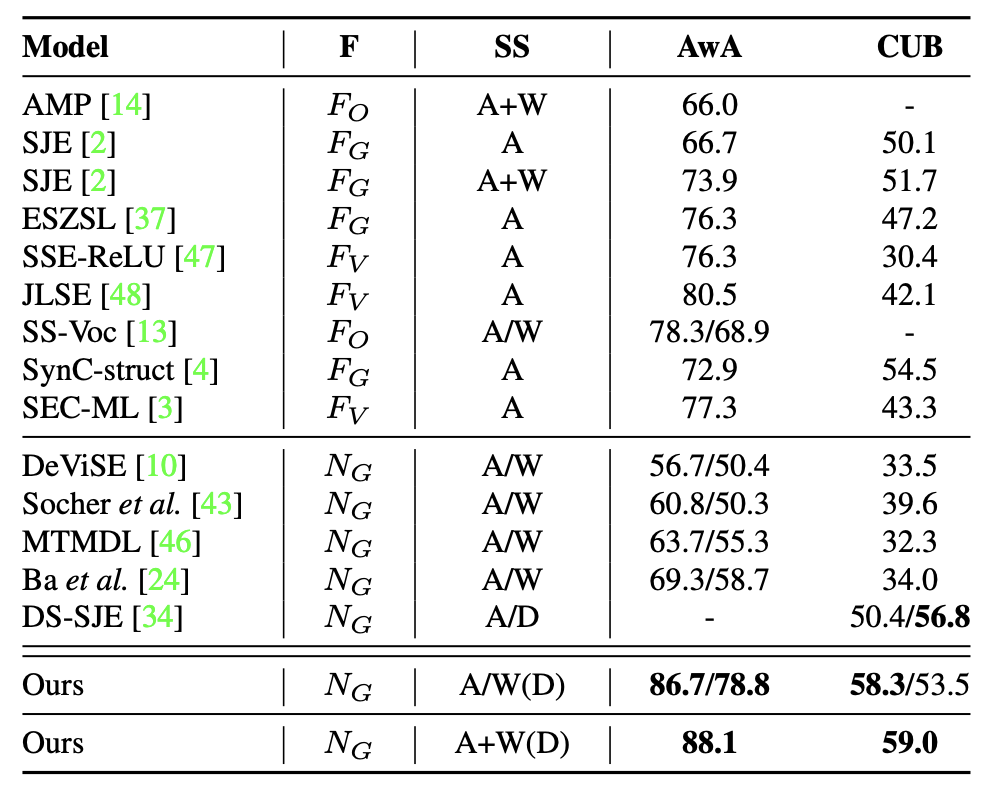

Experiment-wise, this model was benchmarked with AwA (Animals with Attirbutes), CUB (CUB-200-2011), ImageNet 2010 1k, and ImageNet 2012/2010. Their experiment results are shown below — with a semantic space that only utilizes attributes, their deep ZSL model performed 3.8% better than the strongest competitor.

Figure 7: A table that outlines the zero-shot classification accuracy % of various ZPL models when ran against the AwA and CUB benchmark (Zhang, et. al., 2017)

Running the CLIP Model

This report examines how different ways of prompting affect the performance of the CLIP model in classifying unseen data.

For this experiment, we implemented the CLIP model on Google Colab, reaping the benefits of using a T4 GPU to do the computations. For this, the pre-trained model used was ViT-B/16, and we evaluated its performance on the Miniplaces dataset.

...

class ZeroShotNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, vit_model,num_classes=100):

...

for label in labels_temp:

self.labels.append(f"Places: An image of {label}")

...

A model using a baseline prompt format, “A photo of {label},” yields a performance of 63.00%. This provides a point of reference for further study on how prompt engineering may further optimize the performance.

Implementing our Own Ideas

In this section, we describe the iterative process of prompt engineering applied to a CLIP model using the miniplaces dataset. We aimed to analyze how different prompting techniques affect the model’s overall classification accuracy. Below, we summarize the different strategies employed, the observed outcomes, and potential reasons for their success or limitations.

Baseline

The baseline prompt is simplistic and gives minimal contextual information about the label. Although this generic approach works quite well for the model ViT-B/16, the lack of specificity may limit the model’s ability to disambiguate between visually similar classes or capture nuances in the dataset.

Label-Specific Descriptions

class ZeroShotNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, vit_model,num_classes=100):

...

for label in labels_temp:

if label == 'cemetery':

self.labels.append(f"A cemetery with rows of gravestones and a peaceful atmosphere.")

else:

self.labels.append(f"A photo of {label}") #TODO: do prompt engineering HERE

...

Accuracy: 0.6305

This approach is more specific to particular labels and thus can give richer context to the model. However, the minimal improvement in accuracy suggests that while descriptive prompts may add value, the variability and quality of these label-specific prompts could impact results. For example, overly verbose or unevenly detailed descriptions might have diluted their effectiveness.

Fine-Tuned Descriptive Prompt

class ZeroShotNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, vit_model,num_classes=100):

...

self.labels = []

for label in labels_temp:

self.labels.append(f"A detailed photo of a {label}, showing its key features and environment.")

...

Accuracy: 0.6742

This prompt attempts to correct the unevenly detailed descriptions in the previous prompting technique by avoiding the label-specific prompts. Instead, this fine-tuned prompt focuses on detail and environmental context, perhaps encouraging the model to focus on key discriminative features of each class. By focusing on key features and environment of an image, it can lead it to perform better. While the improvement over the prior method is marginal, it suggests that detailed prompts may offer diminishing returns when the model has already reached a strong contextual understanding.

Further Fine-Tuned Specificity

class ZeroShotNet(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, vit_model,num_classes=100):

...

self.labels = []

for label in labels_temp:

self.labels.append(f"Places: An image of {label}.")

...

Accuracy: 0.6767

Finally, adding a category cue like “Places:” provides a broader context for classification, which allows the model to better interpret the label within the scope of the dataset. It is possible that this cue is able to signal to the model that we are working with a places dataset, which yielded a significant improvement in accuracy, emphasizing the importance of setting a consistent and relevant contextual framework for all prompts.

Additionally the concise phrasing strikes a balance between specificity and brevity. The improved accuracy indicates that overly detailed prompts may not always be beneficial, and clarity with minimal cognitive overhead for the model can yield better results.

Prompts that offer a strong contextual anchor, like those with the category cue “Places:”, serve to guide the model’s responses more effectively than more generic or wordy prompts. This may indicate that a clear scope is helpful in narrowing the model’s attention down to appropriate features, increasing its accuracy. This richness is further added to descriptive prompts by underlining the features that are important; overly verbose, this might be detrimental, as noise might blur important information for the model to deduce. The nature of the miniplaces dataset emphasizes place-related scene recognition and probably fairs better with place-centric context than object-centric specification.

References

[1] A. Radford et al., ‘Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision’, arXiv [cs.CV]. 2021.

[2] Clip: Connecting text and images, http://openai.com/index/clip. 2021.

[3] L. Zhang, T. Xiang, and S. Gong, “Learning a deep embedding model for zero-shot learning,” 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Jul. 2017. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2017.321

[3] Palatucci, et. al. “Zero-Shot Learning with Semantic Output Codes”: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 22 (NIPS). 2009.

[4] Xian, et. al. “Feature Generating Networks for Zero-Shot Learning”: CVPR. 2018.