Peek-A-Boo, Occlusion-Aware Visual Perception through Active Exploration

In this study, we present a framework for enabling robots to locate and focus on objects that are partially or fully occluded within their environment. We split up any robotic tasks into two steps: Localization, where the robot searches for objects of interest, and Task Completion, where the robot completes the task after finding the object. We propose Peekaboo, a solution to the Localization stage to find partially or even fully occluded objects. We train a reinforcement learning algorithm to teach the robot to actively reposition its camera to optimize visibility of occluded objects. The key features include engineering a reward function that incentivizes effective object localization and setting up a comprehensive training environment. We develop a simulation environment with randomness to learn to localize from numerous initial viewpoints. Our approach also includes the implementation of a vision encoder for processing visual input, which allows the robot to interpret and respond to objects and occlusions. We design metrics to quantify the model’s performance, demonstrating its capability to handle occlusions without any human intervention at all. The results of this work showcase the potential for robotic systems to actively improve their perception in cluttered or obstructed environments.

- Introduction

- Prior Works

- Problem Formulation

- Proposed Methods and Evaluation

- Experiments

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Links

- References

Introduction

In dynamic and cluttered environments, robotic systems with visual perception capabilities must be able to adapt their viewpoints to maintain visibility of target objects, even when occlusions or obstacles obstruct their line of sight. Traditional robotic vision systems often address this requirement by either using a large array of static sensors, usually cameras, pointing in different orientations, or by moving a single sensor in a predetermined path. Both approaches have their downsides. Arrays of static sensors are far more expensive than using a single sensor, and rely on the motion of their agent to acquire new viewpoints. Sensors that follow predetermined paths lack the flexibility to capture environment-dependent information about complex scenes common in real-world settings. These limitations serve as critical bottlenecks slowing the advancement of vision-based robotics. Active Vision is a promising field that aims to address these challenges. The goal of Active Vision is to mimic the way that humans perceive their environment: by learning to move and orient a single sensor in ways that capture information important for completing some task.

Active Vision avoids the shortcomings of the other two approaches; the agent uses a single controllable sensor, as opposed to an array of fixed sensors to perceive its environment, and the agent can learn to manipulate its sensor in response to its environment in nuanced ways that a predetermined approach could not.

Recent advances in reinforcement learning (RL) have looked into enabling robots to learn behaviors directly from their interactions with the environment, making it possible to train autonomous systems to explore the environment, allowing for active perception. In robotic vision tasks, RL algorithms can enable a camera mounted on a robotic arm to not only locate objects but also to continuously adjust its position to avoid occlusions and improve object visibility. However, developing such an RL framework requires overcoming several challenges, including creating a robust training environment that mimics the need to shift camera perspectives, and engineering reward functions that incentivize behavior promoting consistent visibility.

We propose Peekaboo, an approach that addresses many of the shortcomings of previous methods. Peekaboo’s key insight is that the Localization and Task Completion steps in manipulation tasks can be decoupled with minimal loss of generality. In practice, when humans perform manipulation tasks, we search our environment for an object before extending a hand in its direction to grasp it. The same logic applies here. Any manipulation task first requires the agent to localize the object, along with anything else critical for completing the task. Peekaboo focuses on this Localization step, but unlike previous works is designed to be robust to very heavy occlusions, and allows the camera to be controlled with many degrees of freedom.

Prior Works

Prior works in Active Vision address similar problems to ours, but all differ in some key areas. While there are many works in Active Vision, we mention those most relevant to our method. A recent approach by researchers at Google Deepmind proposes using navigation data to enhance the performance of cross-embodiment manipulation tasks [8]. The researchers demonstrate that learning a general approach to navigation from sources using different embodiments is key to performing manipulation tasks. Their findings reinforce the notion that navigation is a robotics control primitive that can aid any task, even those that do not explicitly perform navigation.

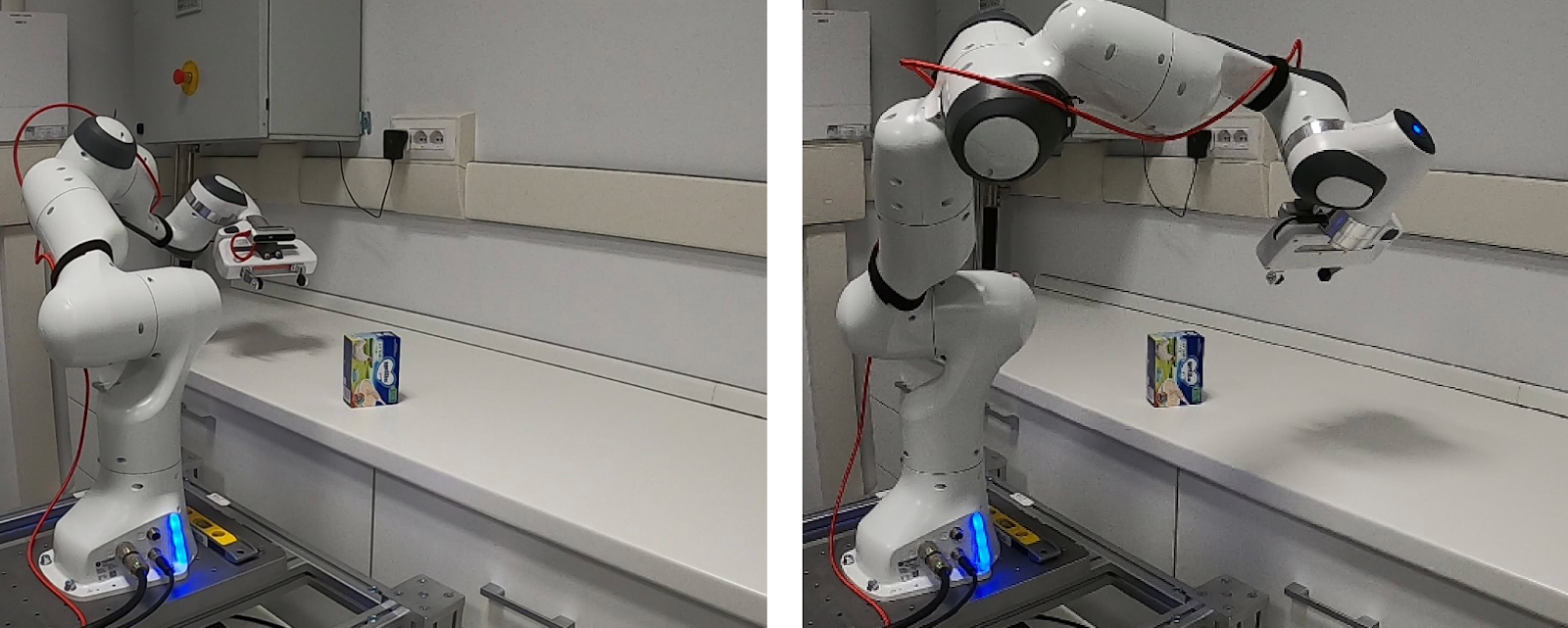

Other works like those by researchers from the University of Texas at Austin have proposed performing complex tasks using an “information-seeking” and an “information-receiving” policy to guide the search task and manipulation task separately [3]. While impressive, their approach Learning to Look is designed to perform complex manipulation tasks in simple unobstructed environments with limited camera motion. In contrast, our goal is to operate in environments designed to hinder search tasks and force the agent to substantially move its camera to succeed. There has also been plenty of work in using Active Vision as a tool to improve performance in well-studied tasks like grasping [6] and object classification [7]. More recently, there has been an increased focus on learning Active Vision policies from human demonstrations using Imitation Learning. Ian Chuang et al. propose a method that allows a human teleoperator to control both a camera and a robotic arm in a VR environment in order to collect near-optimal human demonstration data of Active Vision tasks like inserting a key into a lock.

Using learned Active Vision policies as a method to acquire novel views of objects to aid in object classification.

Two prior works stand out as particularly similar to our task and deserve additional attention. The first approach by Stanford researchers, DREAM, proposes decoupling their agent’s task into an explorative navigation step and exploitative task completion stage, each of which is learned separately [5]. This approach relies on an intrinsic task ID, and leverages memory from previous explorative iterations through a memorization process to aid it in the current iteration. While the researchers demonstrate impressive results, we find that their environment is somewhat limited. Since the researchers are performing navigation, their agent is limited to moving in two degrees of freedom, and rotating in a single degree of freedom. In contrast, our approach freely manipulates the agent in six degrees of freedom. In addition, their task is designed such that the agent can physically access the entire environment: an assumption that is often not true in physical systems in the real world.

Another highly relevant paper from researchers at Carnegie Mellon uses Active Vision to aid a manipulation task in the presence of visual occlusions [1]. The authors propose a task of pushing a target cube onto a target coordinate using a robotic arm, where the agent learns to independently manipulate its robotic arm and the camera from which it sees to avoid physical occlusions preventing task completion. Like DREAM, the proposed method limits the agent to few degrees of freedom in its motion. In addition, the agent operates on fairly “weak” occlusions that rarely impede task completion. Lastly, the authors learn a single policy that jointly manipulates the robotic arm and controls the camera – a process we believe can be decoupled.

Learning to perform manipulation in the presence of visual occlusions by learning to control the camera. The agent jointly learns to control the robotic arm to move the cube onto the target, and control the camera to avoid visual obstructions.

Problem Formulation

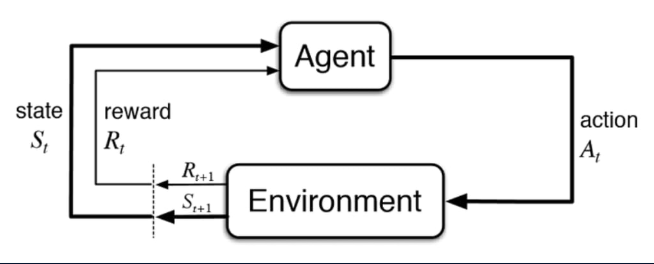

We contribute a novel task formulation unique to Peekaboo, and central to performing occlusion-aware search. We train Peekaboo using a Reinforcement Learning framework, which requires us to define three components: the environment, the agent, and the reward function.

Markov Decision Process (MDP) Framework

The environment is a simple indoor room, containing a central table. On the table lies a randomly positioned target cube and a large randomly positioned wall meant to block the view of the cube.

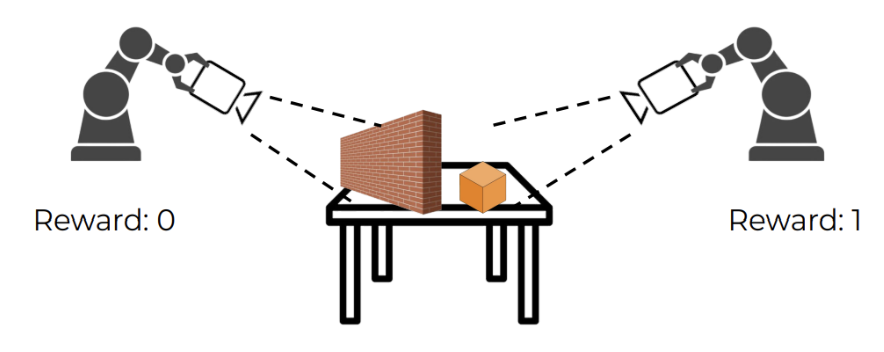

The agent is a 6-DoF Panda robotic arm, initialized to look in a random direction. It can move its end effector in any direction, and rotate its end effector to any orientation. The agent observes its environment through a sensor in its hand that captures images from the hand’s point of view. The reward function is a binary reward function. The value of the reward is one if the target cube is within the frame of the robotic arm’s camera observation. Otherwise, if the cube is off-frame, or occluded by the wall, the value of the reward is zero. This reward function encourages the agent to search its environment until it can see the target cube. Using this particular task, we aim to train Peekaboo such that it can learn to search around occlusions to locate the target cube, regardless of variations in the scene. In summary, we focus on building a flexible, RL-based framework that enables a robotic arm-mounted camera to autonomously determine the optimal perspectives for tracking objects, particularly in environments where occlusions are frequent. To achieve this, we will:

- Introduce randomness

- Randomize both the environment and camera settings during the training phase.

- Ensure the model is robust to variable conditions.

- Include a vision encoder

- Process incoming visual data effectively.

- Incorporate a reinforcement learning (RL) algorithm

- Train the camera’s decision-making process.

- Engineer a reward function

- Emphasize maintaining clear sightlines.

- Penalize occlusions to improve performance.

This work contributes to the growing field of adaptive robotic vision, offering a method for giving robots autonomous, context-aware vision capabilities that can support applications requiring real-time adaptability in unpredictable environments.

Proposed Methods and Evaluation

We propose a two stage RL training framework that allows our robot to first search for and focus on the object of interest, and then complete the desired task by interacting with the object. The focus of our methods will be on training and testing the first stage of this framework, as there are many prior works that focus on task completion. We will refer to this first stage as Localization and the second stage as Task Completion. The Localization phase will consist of training an RL agent that learns to move an egocentric, or first person view, camera to search around occlusions by exploring the environment, with the end goal of localizing the object of interest in its frame of view.

We will approach this problem using a custom environment in Robosuite. Our environment will be built off of the base Lift task environment, with modifications made to create occlusions. Specifically, we will put a wall in between the robotic arm and the cube that the arm is trying to lift. This will be the main occlusion that is dealt with in our Wall task. In its initial frame observation of the environment, the robot will not be able to see the cube it is trying to lift, as it will be covered by the wall. We also introduced cube randomization, camera randomization, and arm randomization. The cube and arm randomization was done through the Robosuite framework. The camera and wall randomization relied on custom quaternions that changed the orientation of our objects. The goal of the overall task is for the robot to search for the cube, find it behind the wall, and then lift it.

Through our two stage framework, we propose a MDP formulation for the Localization stage. The state space consists of the image observations from our robot. We will have a camera attached the end effector of the robotic arm to observe these images. The robot will not have access to ground truth proprioceptive data. The action space consists of modifying the perspective of the camera, which is done through the Cartesian coordinates of moving the robotic arm. The reward function will be as follows:

\[\text{reward} = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if not in view} \\ 1 & \text{if in view} \end{cases}\]

Fig 1. Visualization of our Reward Function.

If the cube is in view, we get a reward of 1, and if it is not, the reward is 0. We will implement this in the environment using the ground truth proprioceptive data of the robotic arm, the wall, and the cube. Using this position data, we can calculate the angle in between the robotic arm and wall, and the robotic arm and the cube. These angles can then indicate if the wall is blocking the robotic arm’s frame of view from the cube or not, which allows us to return a reward of 0 or 1. Given that the robot does not have access to this ground truth data, we are essentially teaching the robot to recognize and search around occlusions when they show up prominently in its camera frame.

Here is a snippet from our code:

def reward(obs):

target_vertices, wall_vertices, camera_position, camera_vec, camera_bloom = preprocess(obs)

# if any corner of the target cube is outside of frame, return 0

for target_vertex in target_vertices:

if not target_visible_in_conical_bloom(target_vertex, camera_position, camera_vec, camera_bloom):

return 0

# if any corner of the target cube is blocked by the wall, return 0

for target_vertex in target_vertices:

for wall_plane in wall_vertices:

if line_segment_intersects_truncated_plane(target_vertex, camera_position, wall_plane):

return 0

# cube is entirely within bloom and is not obstructed

return 1

Once we have set up the Robosuite environment with the camera and reward function, we will train a PPO agent on the MDP formulation of the \(\textit{Localization}\) stage. The image observations will be processed by a pretrained Vision Encoder, which will be frozen during training. The output features of the Vision Encoder will be the inputs to our RL neural networks. Our evaluation will consist of visualizing rollouts and establishing a success rate for the \(\textit{Localization}\) phase. A rollout will be considered a success if the object of interest is seen completely unobstructed in the scene from the perspective of the robot. In order to test for generalization, we will randomize initial states of the robotic arm, the wall, and the cube. Sometimes, the cube will be completely in view, and sometimes it will be completely occluded. It will be up to the robot to learn and decide when it needs to search around the wall and when it has the object of interest in sight.

Our main contributions are the training and evaluation of this first stage. Now that we have run randomized tests, we have set up a foundation to implement the second stage of our proposed method. We can simply use the final, localized state of our first stage as the initial state for our \(\textit{Task Completion}\) stage, which will also be trained using the PPO algorithm. The goal then would be to first use the \(\textit{Localization}\) stage to find the desired object behind any occlusions, and then use the \(\textit{Task Completion}\) stage to execute the task. We can then visualize rollouts of this end to end pipeline and determine the success rate.

This two stage training can then be compared against a baseline of training one PPO agent for the entire task from scratch. In effect we want to show that while one agent is not able to both find the object and finish the task in one go, our two step approach is able to successfully break this down into multiple steps.

Experiments

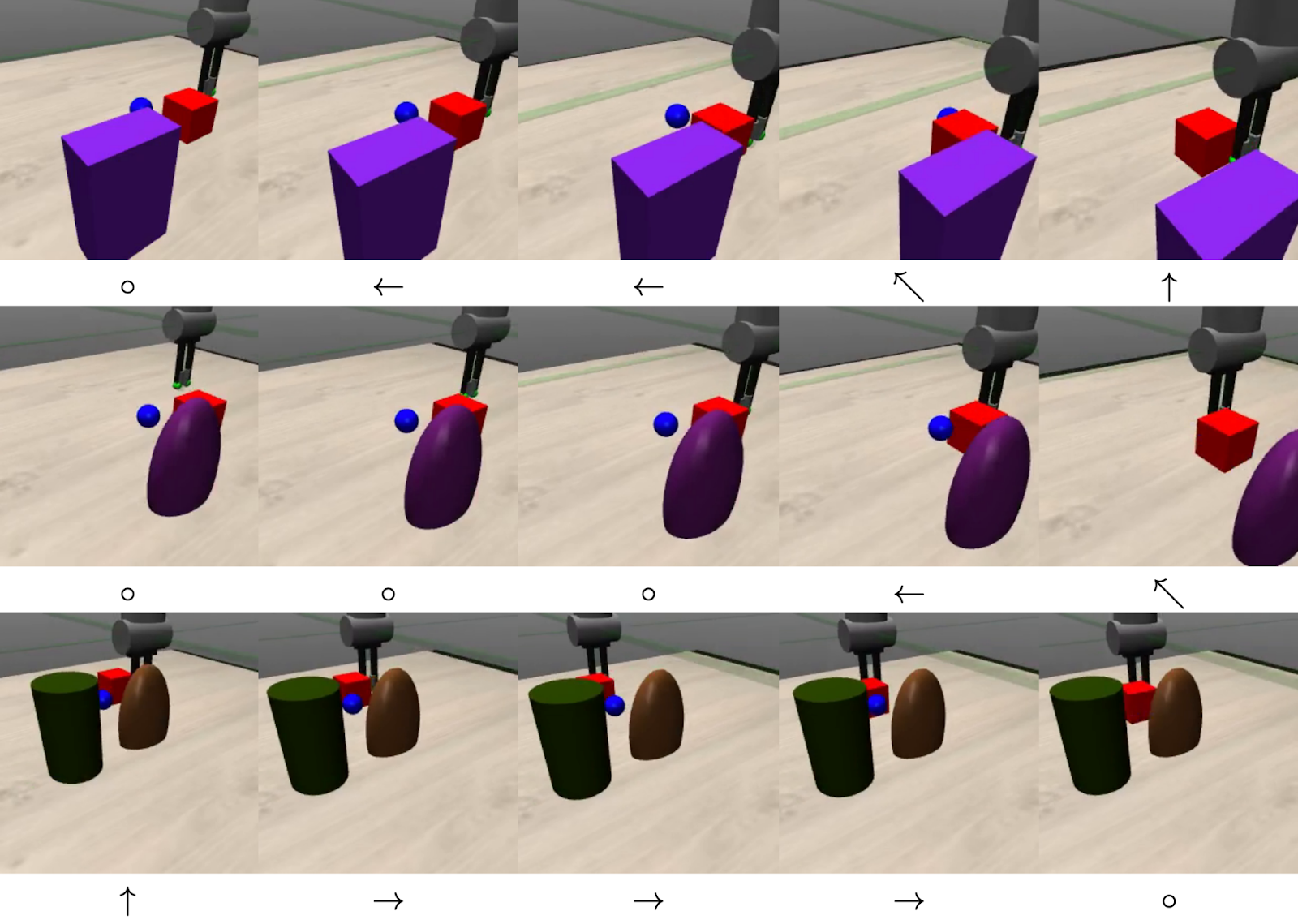

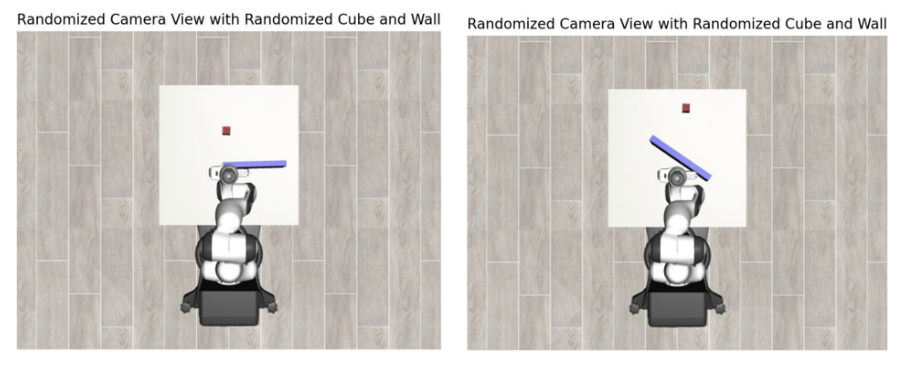

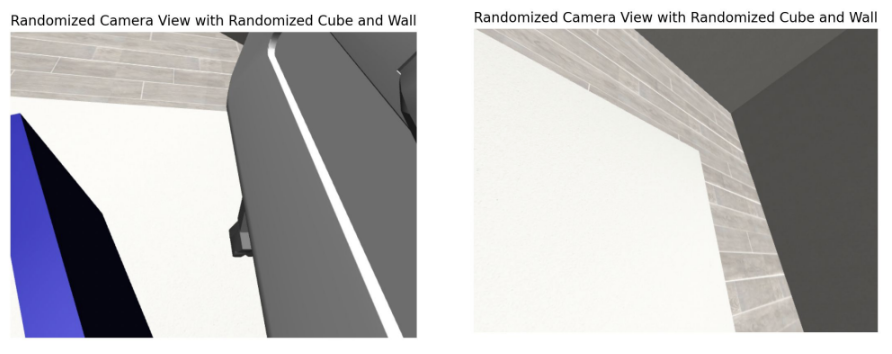

Our experimental environment is in Robosuite. We use a custom Robosuite environment, built off their Lift Environment implementation. This environment provides a target cube object, a robotic arm, a mounted camera on the robotic arm, and a table. We customize this class by adding randomness to the initial positions and orientations of all of the above objects except the table. We also add our own wall, randomized in size, positioning, and orientation. Fig. 2 shows the top down view of our experiment setup. This figure is for visual understanding purposes only and the images from this camera are not used in our training. Fig. 3 shows the first person images from our mounted camera, randomized at each initialization. We use images from this camera to train the arm to move the camera to place the target object in frame. For our training runs, we can train models with varying degrees of randomization. Specifically, in this project, we experimented with turning camera randomization on and off. For all of our training runs, we kept wall and cube randomization always on.

Fig 2. Examples of Top down view of randomized initialization.

Fig 3. Examples of First person view of randomized initialization.

For our training process, we interpret the camera image using DINOv2, a vision transformer based vision encoder, and we feed the results into our reward function. This vision encoder takes in images of size 224 by 224 from the environment and outputs 384 features to our RL policy.

We use a proximal policy optimization (PPO) reinforcement learning algorithm that trains our model to look at the target object. We initialize our RL policy to be a 2 layer MLP with 256 activations per layer, taking the feature inputs from our vision encoder and outputing the action for our robotic arm. We configure this model through the Stable-Baselines3 library. Ideally, we would like to train our policy for 1 million timesteps, which amounts to 2000 episodes, but due to training time constraints, we begin with 200k timesteps, which amounts to 400 episodes. Further discussion of training is presented in our results.

Our metrics for the model that we trained are the rewards that we defined earlier. We set the episode horizon to 500, meaning that there is a total possible reward per episode of 500. A lower reward indicates that the policy struggled to find the cube. The closer the reward is to 500 the better, indicating that our policy was able to localize the cube early in the episode, and learned to keep it within view the entire time.

Results

For our results, we evaluate two main training runs to demonstrate the performance of our method. As we are working with a completely custom environment and task, we are evaluating the performance of an approach to a new problem formulation.

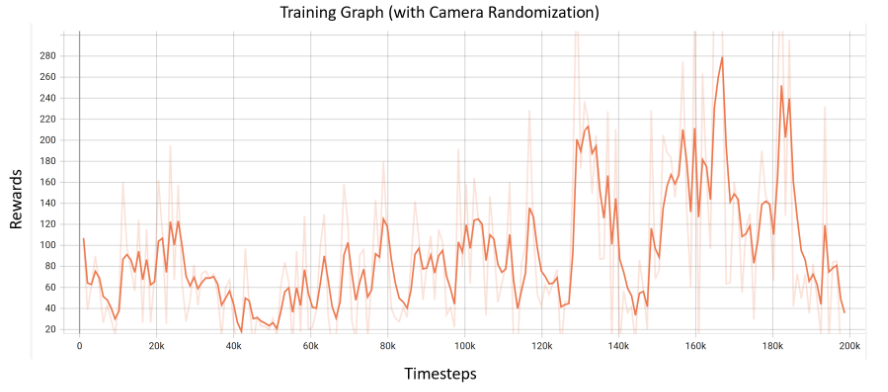

Initially, we trained a model on our fully randomized environment, including randomization of the cube, wall, and camera angle. The reward graph for the training of this model is presented in Figure 4. The model is trained for 200k timesteps, which is about 400 episodes, and took approximately 10 hours to train. We can see that the general trend of the rewards is upwards, with an increase in rewards at around the 130k timesteps mark. However, the rewards are also oscillating after that point, showing variability and lack of convergence to our results.

Fig 4. Rewards Graph for training with randomization of wall, cube and camera.

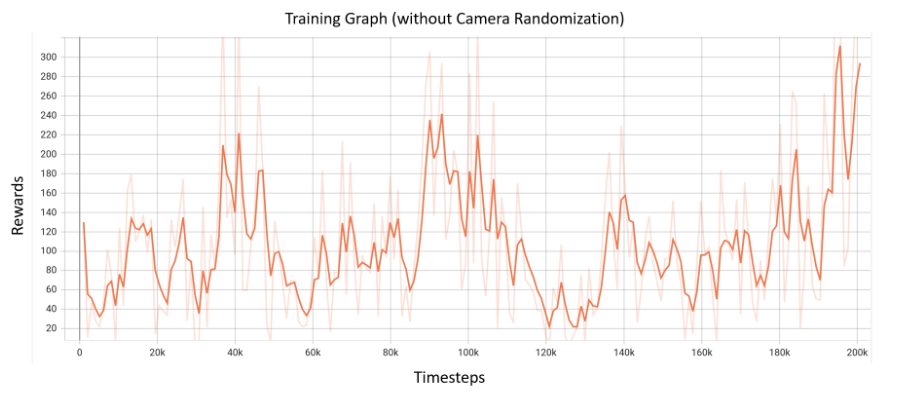

We wanted to demonstrate more stability within our results, so the next model we trained was without camera randomization. The reward graph for this training run is presented in Figure 5. We see an increase in rewards earlier in this graph at 90k timesteps, but then it drops again before picking up towards the end of training. Again, we see that our rewards do not converge.

Fig 5. Rewards Graph for training with randomization of only wall and cube.

In order to test if the model converges, we decided to continue training the model with full environment randomization (camera, wall, and cube) for 1 million time steps, which took 40+ hours. Unfortunately, this training run did not converge either, and showed the same up and down performance that our shorter training runs displayed. Therefore, we see that naively training the model for longer does not improve performance.

Discussion

When we tested our model after training, we saw that our policy’s actions greatly depends on the initial conditions of the task. Since we are randomizing the environment before every episode, the initial conditions could vary from episode to episode. In the case that the wall or cube are in view in the beginning, the model performs reasonably by searching around them. However, we also see many cases when the robotic arm is pointed in an arbitrary direction away from the wall and cube. In this case, it sees just a blank white image of the table. This initial observation gives the robot no information with which to find the cube or even start searching, since that image is the only observation (we do not give the robot proprioceptive data). There is no indication within the image which way it should even search, as that would change from episode to episode due to environment randomization. We believe that this variance in the task causes instability in performance, which aligns with the results we are seeing. When there is a favorable initial condition, the model learns well, but when there is no useful information in the initial condition, performance declines and causes instability in rewards. This performance would explain why our training graphs look the way they do, and why training does not converge simply with training for longer.

It is also important to note that even though we trained for 10+ hours, that only amounted to 400 episodes, which is not very much compared to other environments that train RL models with training episodes in the thousands. This increase in compute goes back to our problem setup, where we settled on the computationally expensive DinoV2 vision encoder with high resolution images, and set the complexity of our task through drastic randomization of our task environment. In future works, especially with a visually simple task environment (the only objects are a wall and cube, with no visual intricacies) it may have been better to use a smaller Vision Encoder like a ResNet or train our own CNNPolicy with lower resolution images. Additionally, we had hoped that the exploration of RL would allow it to learn to overcome drastic randomization, but through our results it seems that we were potentially wrong. It may have been better to start with no randomization and just a wall occluding a cube, and once that was working, we could incrementally add randomization to increase complexity. Once these changes are implemented, we believe that our solution could be a viable solution to the active exploration problem that we are working on.

Conclusion

We present Peek-A-Boo, a two stage Reinforcement Learning framework that aims to break down any task into two stages: Localization/Search and Task Completion. We create a custom task environment with occlusions and randomization, an engineered reward function, and train an RL model with a Visual Encoder to complete the Localization stage. Through our model training, we are able to demonstrate promise in our approach through generally increasing rewards despite variability in training performance.

Future Work

Future work would focus on simplifying the task with less drastic randomization to show stable performance. Then, we can scale up to more complicated tasks. Future work could also look into other ways to stabilize the performance of the model. For instance, the Localization stage of our framework could be approached using IBRL (Imitation Bootstrapped Reinforcement Learning) [4] in order to improve stability through Imitation Learning while allowing the model to also explore the environment through RL. Additionally, another avenue of future work could be automating the reward function using object detection or semantic segmentation on the observation image. We have engineering a reward function using ground truth data, but that may not always be available when applying this framework.

Overall, we see this as a promising first step for active perception and occlusion-aware robotics. We are excited to see the advancements in this field to hopefully one day see robot policies that are able to explore and generalize to any extenuating circumstance that they face in their environment.

Links

Custom feature extractor using the pretrained DINOv2 base model from timm: Link

Stable Baselines Documentation: Link

References

[1] Cheng, R., Agarwal, A., & Fragkiadaki, K. (2018). Reinforcement Learning of Active Vision for Manipulating Objects under Occlusions. Conference on Robot Learning, 422-431. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v87/cheng18a/cheng18a.pdf

[2] Chuang, I., Lee, A., Gao, D., & Soltani, I. (2024). Active Vision Might Be All You Need: Exploring Active Vision in Bimanual Robotic Manipulation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.17435.

[3] Dass, S., Hu, J., Abbatematteo, B., Stone, P., & Martin, R. (2024). Learning to Look: Seeking Information for Decision Making via Policy Factorization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.18964.

[4] Hu, H., Mirchandani, S., & Sadigh, D. (2024). Imitation Bootstrapped Reinforcement Learning. arXiv [Cs.LG]. Retrieved from http://arxiv.org/abs/2311.02198

[5] Liu, E. Z., Finn, C., Liang, P., & Raghunathan, A. (2021, November 12). Decoupling exploration and exploitation in meta-reinforcement learning without sacrifices. Exploration in Meta-Reinforcement Learning. https://ezliu.github.io/dream/

[6] Natarajan, S., Brown, G., & Calli, B. (2021). Aiding Grasp Synthesis for Novel Objects Using Heuristic-Based and Data-Driven Active Vision Methods. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2021.696587

[7] Safronov, E., Piga, N., Colledanchise, M., & Natale, L. (2021, August 2). Active perception for ambiguous objects classification. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2108.00737.pdf

[8] Yang, J., Glossop, C., Bhorkar, A., Shah, D., Vuong, Q., Finn, C., … & Levine, S. (2024). Pushing the limits of cross-embodiment learning for manipulation and navigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.19432.