Camera Pose Estimation, Recent Developments and Robusticity

3D camera pose estimation has become a widely used tool for recovering camera motion and scene structure from video, with applications spanning robotics, AR/VR, and 3D mapping. In this project, we compare a classic SfM baseline (COLMAP) with modern learning-based pipelines (VGGSfM and ViPE) across multiple real-world sequences, evaluating both trajectory quality and stability using qualitative visualizations and simple translation-variability metrics.

- Introduction

- Test Data and Motivation

- COLMAP

- VGGSfM

- ViPE

- Pose Uncertainity: Our Addition

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Camera pose estimation, deciphering a time-indexed sequence of a camera’s environment in all six of its dimensions (position and direction), is a foundational step for downstream 3D reasoning. When camera motion is estimated accurately and consistently across frames, one can reconstruct scene structure, align multi-view observations, and provide reliable geometric supervision for learned world models. In general, however, pose estimation is challenging because it requires inferring a coherent 3D explanation from imperfect 2D evidence: reliable correspondences must be established across viewpoints despite changes in scale, perspective, illumination, and occlusion - and this is especially true of web videos. As a result of these persistent sources of ambiguity and instability, camera pose estimation remains an active area of research, with ongoing work aimed at improving robustness, accuracy, and generalization across diverse scenes and motion patterns.

This report compares three representative pipelines that embody different design philosophies: COLMAP[1], is one of the foundational pipelines in this field, while VGGSfM[2] and ViPE[3] are modern, state-of-the-art methods meant to showcase what is possible in the field today. COLMAP is a classical, geometry-driven structure-from-motion (SfM) and multi-view stereo (MVS) system that emphasizes robust correspondence filtering and iterative bundle adjustment. VGGSfM is a deep, end-to-end differentiable SfM pipeline that replaces several discrete SfM subroutines with learned components, while retaining explicit geometric structure and a differentiable bundle adjustment stage. ViPE is a video-oriented pose engine that estimates intrinsics, motion, and near-metric depth from raw videos by solving a dense bundle adjustment problem over keyframes under complementary constraints, with explicit mechanisms to improve robustness in unconstrained video.

We will begin by sharing the dataset we built for this project, which include web videos that we ourselves designed specifically for this project. Then, we will take a deep dive into each of the three models, and look at how they work as well as how they performed on our dataset. Finally, we will go over our own contributions: a novel way to visualize the outputs of VGGSfM as well as a statistical analysis of the reliability and robustness of camera pose estimation methods.

Test Data and Motivation

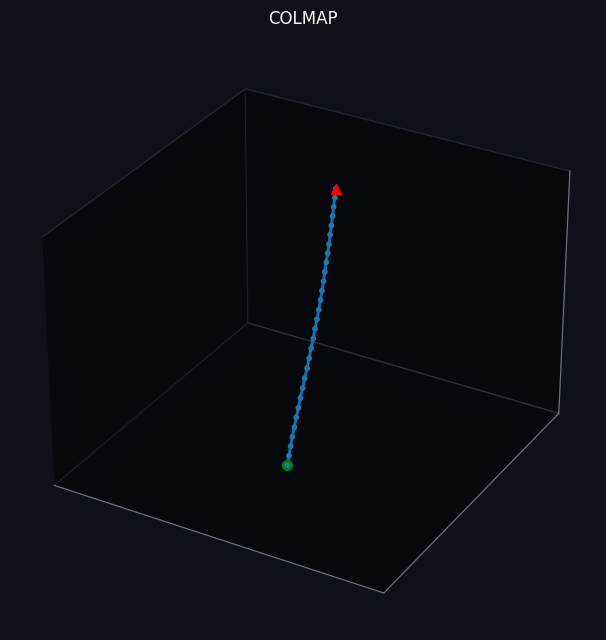

To evaluate robustness under progressively more demanding conditions, we selected three short web-video sequences with deliberately increasing motion complexity and failure-mode coverage. The first sequence is a simple animation with greenery in the background where the camera moves primarily forward. This baseline is chosen because it typically provides stable appearance statistics and relatively smooth motion, allowing us to verify that each method can produce a complete and coherent trajectory under favorable conditions.

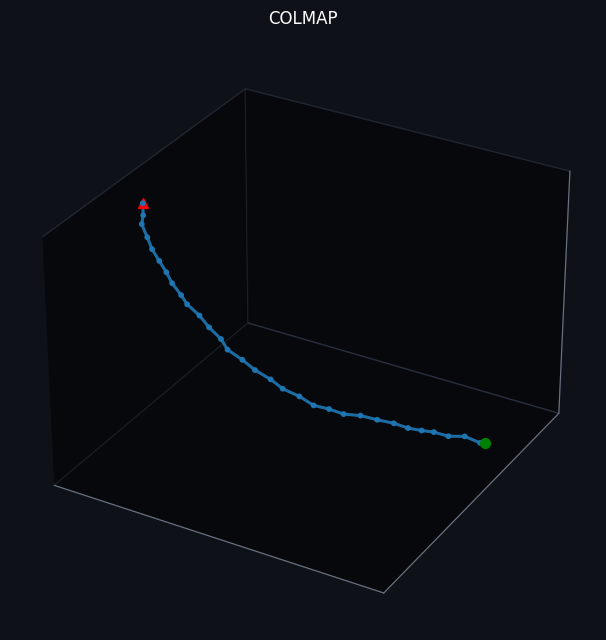

The second sequence shows a camera moving around a stationary object, the UCLA Bruin bear statue. This scene is more challenging because the camera continuously changes its viewpoint as it rotates around the object, making it harder to consistently match visual features across frames. Parts of the object may also become hidden or revealed during the motion, and the background can change relative to the foreground. This sequence tests whether a method can produce a stable and coherent camera trajectory while circling an object and revisiting similar viewpoints.

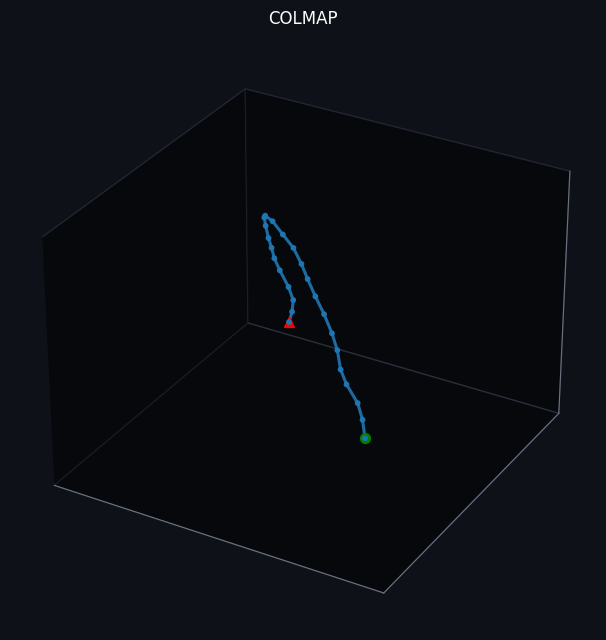

The third sequence is the most adversarial: walking up to a stationary car and then walking backward, with sharp movements. This setting is difficult because abrupt motion increases blur and tracking failures, while backwards motion creates repeated viewpoints that can trigger drift, discontinuities, or inconsistent scale behavior if the method fails to recognize revisited observations with earlier parts of the trajectory. This sequence therefore acts as a test for correspondence robustness and temporal consistency.

COLMAP

COLMAP is a general-purpose SfM and MVS pipeline that reconstructs camera motion and sparse scene structure from a set of images and then, optionally, performs dense reconstruction. In the present setting, video frames are treated as an ordered image collection, and the sparse SfM stage is the primary component of interest because it is responsible for camera pose recovery. The central assumption of this model is that a sufficient number of reliable correspondences across views can be established; given those correspondences, camera parameters and 3D points are recovered by minimizing reprojection error, typically through repeated bundle adjustment.

Overview

The classical incremental SfM pipeline implemented in COLMAP can be described as a sequence of interlocking stages: feature extraction, feature matching, geometric verification, incremental reconstruction with image registration and triangulation, outlier filtering, and repeated bundle adjustment. Feature extraction produces a set of keypoints and descriptors for each frame. These descriptors are engineered to be repeatable across changes in viewpoint and illumination, with SIFT[4] and related features historically serving as a robust default family in SfM literature. Feature matching then proposes candidate correspondences between frames by comparing descriptors; while video sequences often encourage sequential matching, the conceptual objective is the same in all pairing strategies: identify pixel locations in different frames that likely correspond to the same 3D point.

Geometric verification is the first critical safeguard against drift and failure. It uses robust model fitting, typically framed around two-view epipolar geometry, to discard descriptor matches that do not satisfy multi-view constraints. Once a sufficiently consistent set of verified correspondences exists, incremental reconstruction begins by initializing from a strong seed configuration and then registering additional frames one at a time. For each newly registered frame, the system estimates the camera pose by solving a PnP-style problem against the current partial 3D model, then triangulates new 3D points using multi-view observations. This interleaving of pose estimation and triangulation is followed by outlier filtering to remove points or observations with inconsistent reprojection behavior, and by bundle adjustment to jointly refine camera poses, intrinsics (when optimized), and 3D point positions to reduce accumulated error.

Bundle adjustment is the mechanism that enforces global consistency in classical SfM. Conceptually, it ties together all frames that share track observations by optimizing a single objective that penalizes discrepancies between observed 2D keypoints and the projected locations of their associated 3D points under the current camera parameters. Because the objective is non-convex, the quality of the initial correspondences and initialization strongly influences whether the method converges to a coherent solution or becomes trapped in a locally inconsistent configuration.

Under favorable conditions with stable texture and moderate motion, COLMAP’s incremental pipeline can achieve high-quality trajectories because geometric verification and bundle adjustment impose strong constraints. However, the method’s dependence on repeatable sparse keypoints makes it sensitive to blur, large appearance changes, and dynamic content that introduces non-rigid correspondences. In forward motion cases, the effective triangulation baseline between adjacent frames may be small, which can weaken depth conditioning and increase sensitivity to frame sampling decisions. In orbiting motion, viewpoint changes can improve parallax but also increase the risk of track fragmentation and outlier matches on repeated patterns. In backwards motion with sharp movements, intermittent correspondence issues can cause incomplete registration or discontinuities that are difficult to repair once drift has begun.

Results

Our trajectories estimated by COLMAP exhibit largely accurate tracking, as reflected by the near-linear path in Dataset 1, the orbital arc in Dataset 2, and the clear reversal in direction in Dataset 3. However, COLMAP’s performance and runtime are highly sensitive to both input video quality and pipeline tuning. In particular, motion blur, rapid camera movements, low-texture or textureless surfaces, and the presence of moving objects can degrade correspondence quality and, in turn, destabilize pose estimation. Using more frames and applying more thorough optimization can improve consistency, but this typically increases runtime substantially and may still fail when the camera does not revisit sufficient overlapping content for robust constraints. In practice, we found that COLMAP performs best when frames are carefully selected and the scene contains strong, static textures. Finally, because COLMAP’s processing in our setup was largely CPU-bound and comparatively slow, we sometimes adopted suboptimal hyperparameter settings to reduce computational load and maintain a reasonable runtime.

VGGSfM

VGGSfM proposes a fully differentiable SfM pipeline in which the major stages of classical SfM are redesigned so that the entire system can be trained end-to-end. The motivating observation is that traditional SfM pipelines rely on discrete, combinatorial subroutines such as pairwise matching followed by correspondence chaining, and on non-differentiable solvers, which restrict the ability to train a system whose intermediate representations are optimized to be useful for the final reconstruction objective. VGGSfM instead centers the pipeline around learned representations that are explicitly shaped to produce camera poses and structure that subsequent optimization can refine.

Overview

A key shift in VGGSfM is that correspondence estimation is built on deep 2D point tracking that directly outputs pixel-accurate tracks across multiple frames, rather than constructing tracks indirectly by chaining pairwise matches. This design aims to improve track continuity and reduce failure cascades caused by small pairwise matching errors that accumulate over time. The tracks, together with image features, are then used to recover all camera poses jointly, rather than incrementally registering one image at a time. VGGSfM explicitly describes a Transformer-based mechanism that estimates all cameras simultaneously from image and track features, which avoids some of the brittleness associated with early-stage incremental decisions and also fits naturally into an end-to-end differentiable framework.

After obtaining an initial estimate of camera parameters, VGGSfM reconstructs 3D points and refines the solution through a differentiable bundle adjustment layer. VGGSfM does this with a fully differentiable second-order solver so that gradients can flow through the optimization step during training. Conceptually, this means that earlier components, tracking, camera initialization, and point initialization, can be trained to produce intermediate outputs that make the downstream optimization problem better conditioned and easier to solve.

From the perspective of pose estimation on video, the effective meaning is that VGGSfM attempts to learn correspondences and initializations that remain stable under real-world issues such as blur and viewpoint changes, while still being grounded in an explicit geometric refinement stage rather than relying solely on direct pose regression.

Results

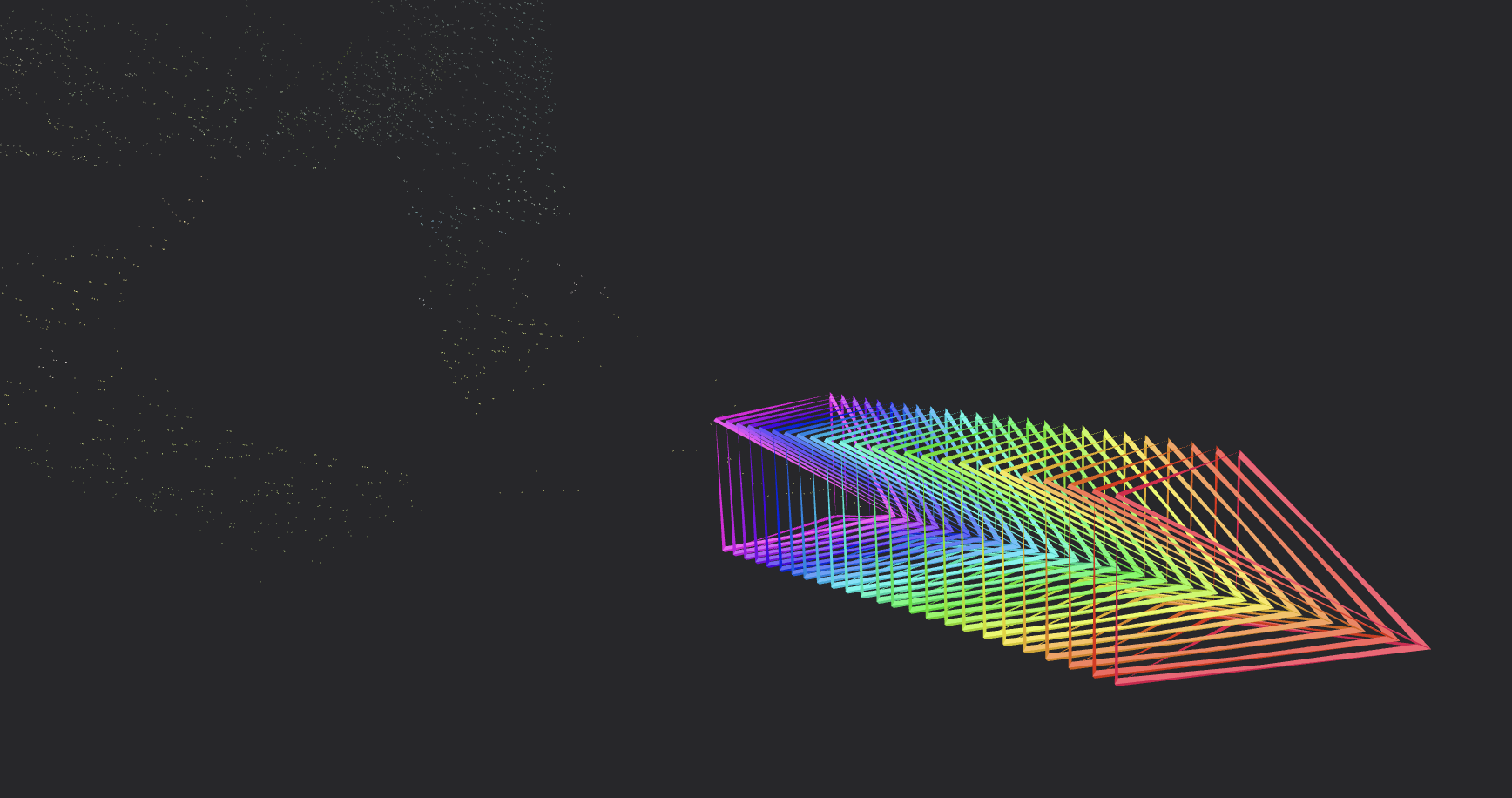

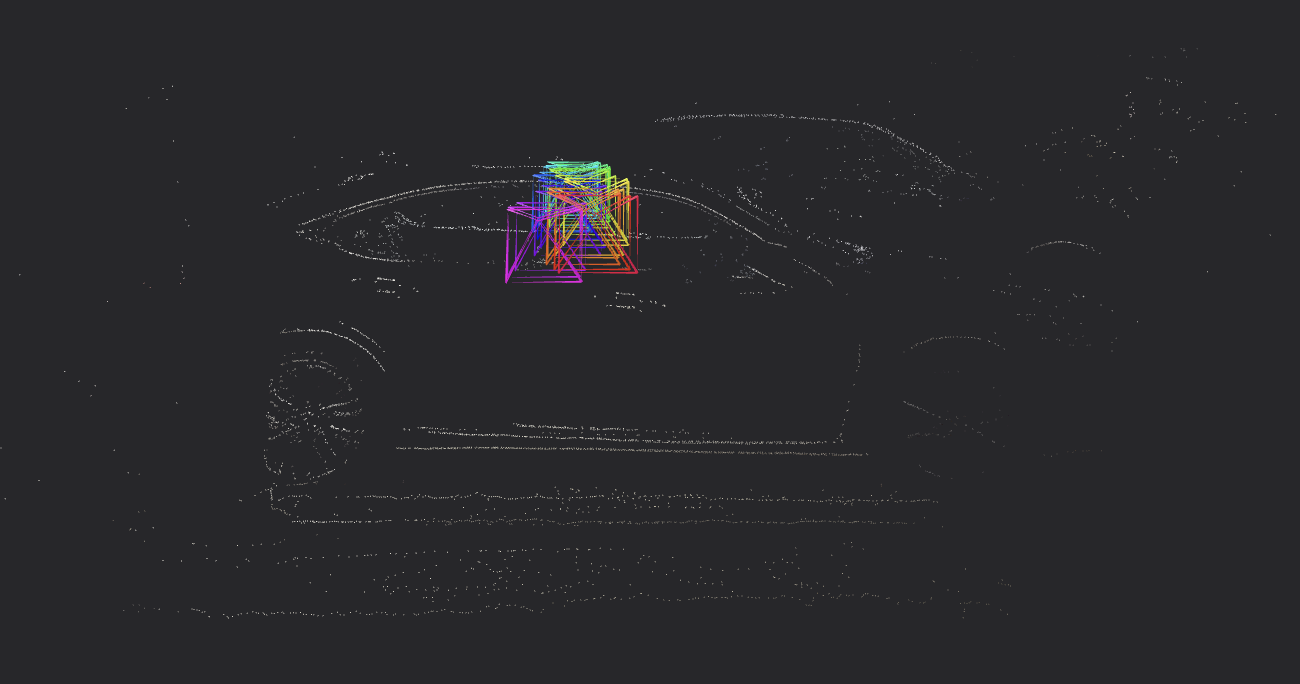

Our trajectories plotted by VGGSfM were generally stable and visually consistent. We see a smooth, coherent camera trajectory along a path with gradual orientation changes. Additionally, the point cloud provides reassurance that the model is performing well, although it is not the metric of interest. For instance, we can clearly make out the bear statue and car.

Because VGGSfM is designed for structure-from-motion with learned components, it can be more robust than COLMAP on difficult video, but its runtime and quality still depend on sequence length and on how much overlap the video provides. Similar to the other SfM pipelines, it can still drift or degrade when the scene is highly dynamic, lacks distinctive features, or when the camera motion is too fast with little revisiting of the same areas. In our experiments, VGGSfM was comparatively fast to run because of CUDA support compared to COLMAP, but we were still constrained by GPU memory limits, which also sometimes led to limiting model size parameters to avoid out-of-memory failures.

ViPE

ViPE is a video pose engine designed to estimate per-frame intrinsics, camera poses, and dense near-metric depth from unconstrained raw videos. Its design is entirely video-centric: rather than treating frames as an unordered photo collection, it constructs and optimizes a keyframe-based representation and solves a dense bundle adjustment problem under multiple complementary constraints. This emphasis reflects the realities of web video, where sparse feature pipelines often struggle due to blur, dynamic objects, and non-ideal camera characteristics.

Overview

At its core, ViPE solves dense bundle adjustment over keyframes by combining three complementary sources of geometric constraint: a dense flow constraint derived from the DROID-SLAM[5] network to provide robust correspondences, a sparse point constraint based on cuVSLAM[6] for sub-pixel accuracy in stable regions, and a depth regularization term derived from monocular metric depth networks to address scale ambiguity and improve consistency. This formulation is important because each term compensates for weaknesses of the others: dense flow can remain informative when sparse corners are scarce, sparse features can be precise when dense estimates are noisy, and depth priors can stabilize the otherwise underdetermined scale and depth degrees of freedom that appear in monocular geometry.

ViPE also emphasizes keyframing and temporal depth consistency. An additional smooth depth alignment step that fuses bundle-adjustment-derived depth with video depth estimates to produce temporally consistent, high-resolution metric depth. As a whole, the system aims not merely to output a plausible camera trajectory, but to produce a trajectory and depth field that are mutually consistent and usable for downstream 3D tasks.

A notable practical feature is that ViPE is intended to handle diverse camera models, including standard perspective, wide-angle, and 360° panoramic inputs, reflecting the vast variety of web video sources. This matters in practice because pose estimation quality can degrade substantially when the assumed projection model diverges from the true camera geometry, especially for wide-angle footage.

Results

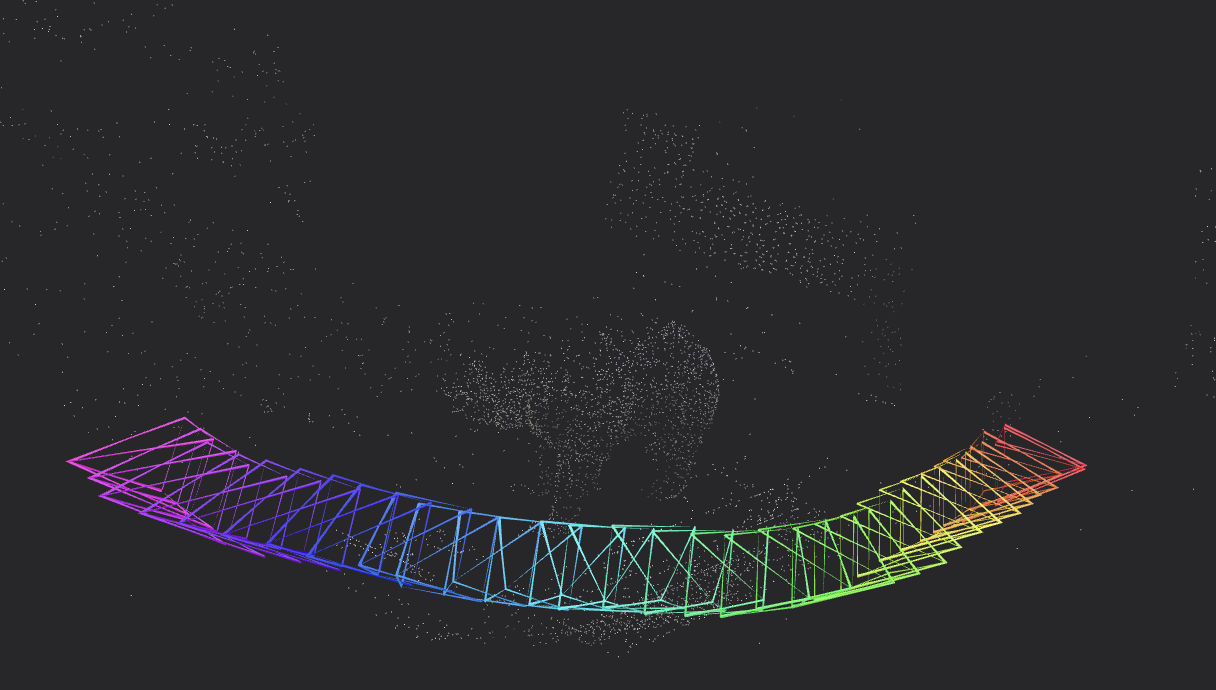

For ViPE’s visualizations, we implemented our own custom Open3D visualization pipeline because ViPE doesn’t provide a built-in way to render the specific plot we needed (3D pose predictions overlaid on a reconstructed scene with a trajectory-style trace). We exported ViPE’s outputs into COLMAP text format, which includes intrinsics, per-frame poses, and a point cloud, rendered the point cloud with predicted camera poses, and highlighted the camera center with a red dot to show the camera’s path over time.

Of all the three pipelines and dataset videos, ViPE makes the only clear error (beyond the pipeline outright failing / producing uninterpretable results). In Dataset Video 2, ViPE’s trajectory veers away from the true path at the end, continuing to move laterally to the left as opposed to following the true trajectory which took a turn and continued to wrap around the bear statue. That said, overall, the Open3D visualization indicates that ViPE’s estimated camera poses follow the reconstructed scene well. This is apparent as the camera poses remain plausibly aligned to the point cloud and the red centerline forms a mostly smooth trajectory rather than erratic jumps.

Compared to classic COLMAP, ViPE can be more robust and convenient on raw video because of its modern end-to-end pipeline that handles challenging frames and continuous sequences, whereas COLMAP often requires careful frame selection and can be more brittle when the footage has blur or rapid motion.

Pose Uncertainity: Our Addition

From COLMAP’s estimated 3D camera trajectory, we extract the coordinate of our camera in space (tx, ty, tz) for each frame of the video. Using this data, we implemented methods of calculating “pose uncertainty”, essentially how reliable the trajectory is, both across independent runs of the model as well as over time within each individual run.

Temporal Translation Uncertainty

We estimate “pose uncertainty” from a translation-only camera trajectory by measuring local stability within a small time window. This is because some parts of the trajectory are clearly more stable than others, due to factors such as good texture, while other parts can “jitter” due to blur, low texture, repetitive patterns, or temporary tracking issues. As a result, if the pose estimate is reliable, nearby frames should agree on (tx,ty,tz). However, if it’s unreliable, the translations in a short temporal neighborhood will vary more.

In practice, we compute this uncertainty using a sliding temporal window centered at each frame: for frame t, we collect the translations from frames [t−W, t+W], compute the 3×3 covariance matrix of (tx,ty,tz) within that window, and assign the resulting trace-based score back to the center frame.

Specifically, we summarize that covariance with:

trace_trans_cov=tr(Σ)

which is the sum of the variances along the three axes. Larger values mean greater local scatter (less stable pose estimates).

We also report:

trans_uncertainty=sqrt(trace_trans_cov)

so the uncertainty is in the same units as translation (instead of squared units). This acts like a local “RMS jitter magnitude” around each frame.

This design reflects how stable the estimated trajectory is locally, and it depends on the chosen window size W. Specifically, smaller windows emphasize jitter whereas larger windows capture slower drift.

Additionally, we use the trace because it’s simple and stable and directly interpretable as “total variance” across axes.

Run-to-Run Translation Uncertainty

In addition to our temporal translation uncertainty, we also implemented a simple method that quantifies how stable the estimated translation is across repeated N runs at each frame.

Our process for constructing this metric is as follows. For each fixed frame c, we have N translation vectors (tx, ty, tz). We then stack the N translations into an N x 3 array and compute a 3×3 sample covariance across runs. This matrix (Σ) captures both the per-axis variability (how much (tx, ty, tz) fluctuate) and how those fluctuations co-vary between axes.

Similar to our temporal translation uncertainty, we summarize that matrix with trace_trans_cov, defined as: trace_trans_cov=tr(Σ)

Since the trace is the sum of the diagonal variances, it acts like a “total translation spread” score. As such, larger trace means translations are less stable and vary more across runs whereas smaller trace means they are more stable and agree more.

Again, we define trans_uncertainty as our single confidence/uncertainty score per frame:

trans_uncertainty=sqrt(trace_trans_cov)

Results

In our output across 15 samples, the run-to-run translation uncertainty we obtained is as follows: the average trace over all frames is 0.1865 and the average uncertainty is 0.3761, with uncertainty lowest around the middle frames and highest at the ends, giving a U-shaped stability pattern. Analyzing the temporal translation uncertainty over 25 frames, the average trace is 6.71 and the average uncertainty is 2.55, where we observed a similar stability shape.

In the run-to-run translation uncertainty case, the average trace and average uncertainty seem to be lower than what we were expecting. At first, we had thought these values would be higher since, going into the project, we had the preconceived notion that these models vary a lot across different types of scenes. In the end, it seemed that these models performed better with more stability and less run-to-run translation uncertainty than we expected. However, we did observe there to be more temporal translation uncertainty which is consistent with the small fluctuations that we saw in our trajectory plots.

We note that our analysis used a relatively small number of runs (n = 15) and a short sequence length (25 frames) due to compute and time constraints. In future work, it would be useful to repeat these experiments with more runs and longer frame sequences to test whether the same trends, and the U-shaped stability pattern in particular, persist at larger scales.

Conclusion

Across this project, we demonstrated how 3D camera pose estimation can be applied to varied real-world sequences, moving from an “easy” online example (tree) to our own capture with more realistic challenges (Bruin Bear), and then to reverse-trajectory motion (car). Using this progression made it easier to separate what is inherently pipeline-friendly from what may be more difficult for the models due to blur, low texture, repeated patterns, or unfavorable viewpoints. Importantly, our trajectory visualizations gave us a practical and intuitive way to diagnose if any of the methods faced stability, drift, and inconsistency.

COLMAP provided a strong baseline for sparse reconstruction and camera trajectory recovery but it was slow in our setup because it relied mainly on the CPU and was highly sensitive to parameter tuning. This motivated our comparison with newer learning-based approaches, including VGGSfM and ViPE. VGGSfM produced generally stable, smooth, and visually consistent trajectories, and its point clouds helped qualitatively confirm good reconstructions (e.g., we could clearly make out the bear statue and car). ViPE lets us focus directly on reliability and interpretability, which were clearly demonstrated by our Open3d visualizations. Finally, we complemented our work with summary metrics for run-to-run translation variability and temporal translation variability.

In conclusion, our models were mostly effective in reconstruction of 3D camera pose estimation and trajectory recovery. Looking ahead, a natural next step is to scale these experiments to longer sequences and more runs, and to test systematically under harder conditions, such as controlled blur, low light, or highly dynamic scenes, to see when the same stability patterns hold.

References

[1] Johannes L. Schonberger, Jan-Michael Frahm; Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2016, pp. 4104-4113

[2] J. Wang, N. Karaev, C. Rupprecht, and D. Novotný, “VGGSfM: Visual Geometry Grounded Deep Structure From Motion,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2024

[3] J. Huang, Q. Zhou, H. Rabeti, A. Korovko, H. Ling, X. Ren, T. Shen, J. Gao, D. Slepichev, C.-H. Lin, J. Ren, K. Xie, J. Biswas, L. Leal-Taixé, and S. Fidler, “ViPE: Video Pose Engine for 3D Geometric Perception,” arXiv:2508.10934, 2025

[4] D. G. Lowe, “Object Recognition from Local Scale-Invariant Features,” in Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 1999, pp. 1150–1157

[5] Z. Teed and J. Deng, “DROID-SLAM: Deep Visual SLAM for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras,” in Proceedings of the 35th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2021.

[6] A. Korovko, D. Slepichev, A. Efitorov, A. Dzhumamuratova, V. Kuznetsov, H. Rabeti, J. Biswas, and S. Pouya, “cuVSLAM: CUDA accelerated visual odometry and mapping,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.04359, 2025.