Human Pose Estimation in Robotics Simulation

[Project Track] Human pose estimation is the task of detecting and localizing key human joints from 2D images or video. These joints are typically represented as keypoints connected by a skeletal structure, forming a pose representation. Pose estimation has found applications in areas such as physiotherapy, animation, sports analytics, and robotics.

- Abstract

- Project Overview

- Dataset and Methods

- Results and Findings

- Further Discussion

- Conclusion

- References

Abstract

Human pose estimation is the task of detecting and localizing key human joints from 2D images or video. These joints are typically represented as keypoints connected by a skeletal structure, forming a pose representation. Pose estimation has found applications in areas such as physiotherapy, animation, sports analytics, and robotics.

In robotics, pose information can act as an interface between visual perception and motion control. Translating observed human motion into robot joint commands, however, remains a challenging problem due to differences in embodiment and the ambiguity of 2D observations. In this project, we explore a pipeline that uses a pretrained human pose estimation model to extract 2D keypoints and trains a secondary model to predict robot joint angles from these poses. The goal is to investigate how pose representations can be mapped into a form suitable for robotic motion and simulation.

Project Overview

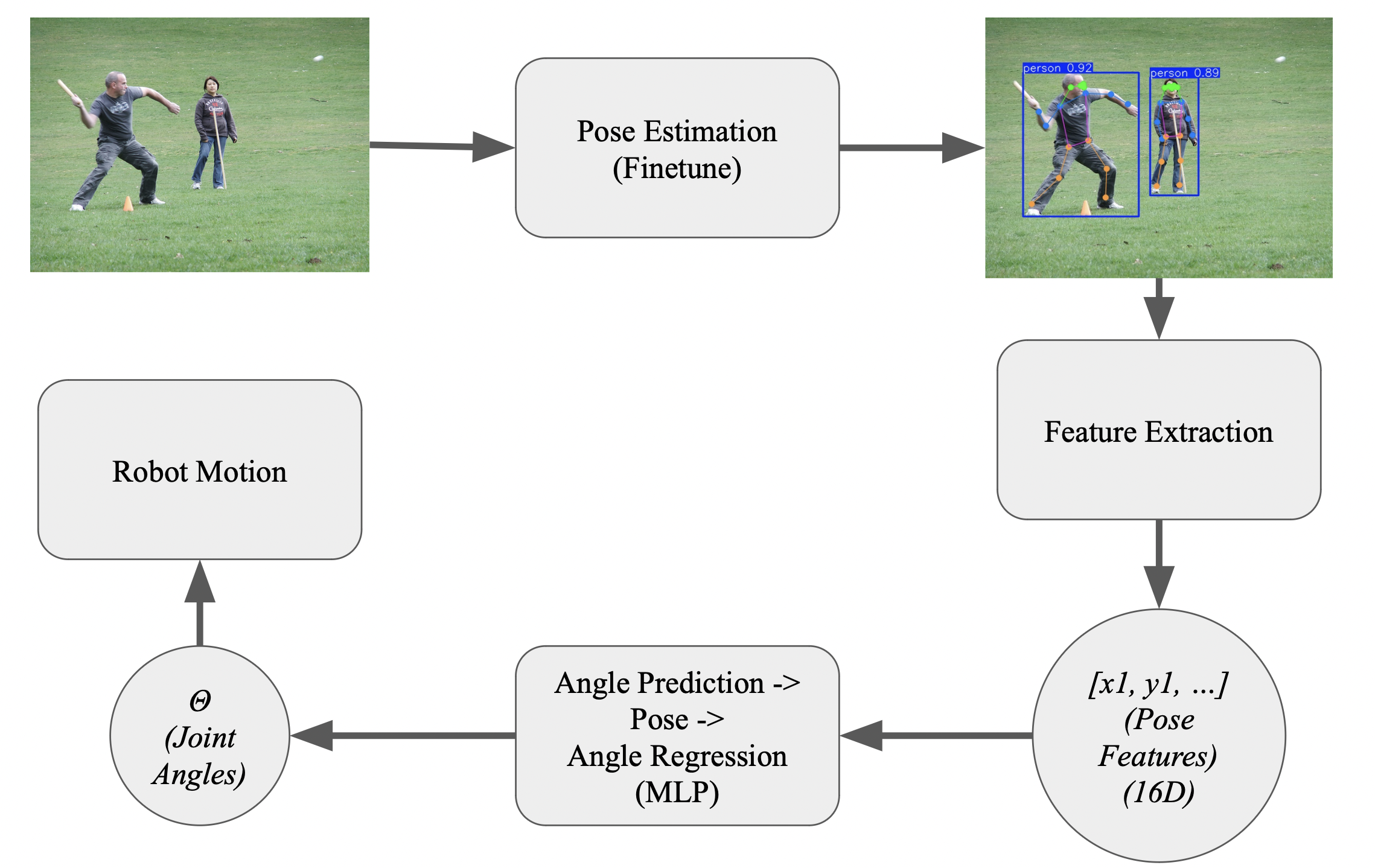

The core idea of this project is to transform human motion, observed through a camera, into robot joint movements. Given a sequence of images or video frames, a finetuned pose estimation model extracts 2D keypoints representing human joint locations. From these poses, joint angles are computed analytically and used as supervision to train a regression model that predicts joint angles directly from pose features.

At a high level, the pipeline consists of the following stages:

- Pose Estimation: Apply a finetuned pose estimation model to extract 2D human keypoints.

- Feature Extraction: Convert raw keypoints into a normalized pose representation.

- Angle Computation: Analytically compute joint angles from keypoints.

- Learning-Based Mapping: Train a neural network to predict joint angles from pose features.

- Simulation: Use predicted angles to drive a simplified robot model in simulation.

If successful, the model should learn to approximate the joint angle computation given a pose input, enabling real-time pose-to-robot imitation.

Dataset and Methods

Pipeline

Fig 3. Image showcasing Project Pipeline [1].

Dataset

To obtain a large and diverse set of human poses, we rely on the COCO dataset, which provides images containing people in a wide range of poses and environments. Rather than training a pose estimator from scratch, we use a pretrained pose estimation model to extract 2D keypoints from these images.

Two pose estimation frameworks were initially considered: Google’s MediaPipe Pose [2] and the YOLOv8 pose estimation model trained on COCO [1]. While MediaPipe Pose produced high-quality keypoints, the YOLOv8 model was ultimately selected for simplicity and closer alignment with the COCO dataset. The pose estimator is optionally fine-tuned on COCO pose annotations; however, the primary focus of this project is not improving pose detection accuracy, but using pose estimation as an intermediate representation for robotic motion.

The pose model is applied to images to extract 2D keypoints for each detected person. Each detection yields a set of keypoints corresponding to major body joints, which are then used for feature extraction and joint angle computation.

Feature Representation

From the extracted keypoints, we select a subset of upper-body joints relevant to arm motion: shoulders, elbows, wrists, and hips. To ensure consistency across poses, the joint coordinates are normalized by centering them at the midpoint of the hips and scaling by the distance between the hips. This normalization makes the representation invariant to global translation and scale. Each pose is represented as eight joints, each with an (x,y) coordinate, resulting in a 16-dimensional feature vector. This compact representation captures the essential structure of the upper body while remaining simple enough for efficient learning.

Angle Computation

Joint angles are computed analytically from 2D keypoints using vector geometry and serve as ground truth supervision for training. Given keypoint locations for the shoulders, elbows, wrists, and hips, limb vectors are constructed to represent the orientation of each body segment.

For each arm, the upper arm vector is defined from the shoulder to the elbow, and the forearm vector from the elbow to the wrist. The torso vector is defined from the hip to the shoulder. Joint angles are then computed using the angle between two vectors:

\[\theta(a, b) = cos^{-1}(\frac{a \cdot b}{||a|| \cdot ||b||})\]The elbow angle is computed as the angle between the upper arm and forearm vectors, while the shoulder angle is computed as the angle between the torso and upper arm vectors. This procedure is applied symmetrically to both the left and right arms. The resulting angles are expressed in degrees and used as regression targets during training.

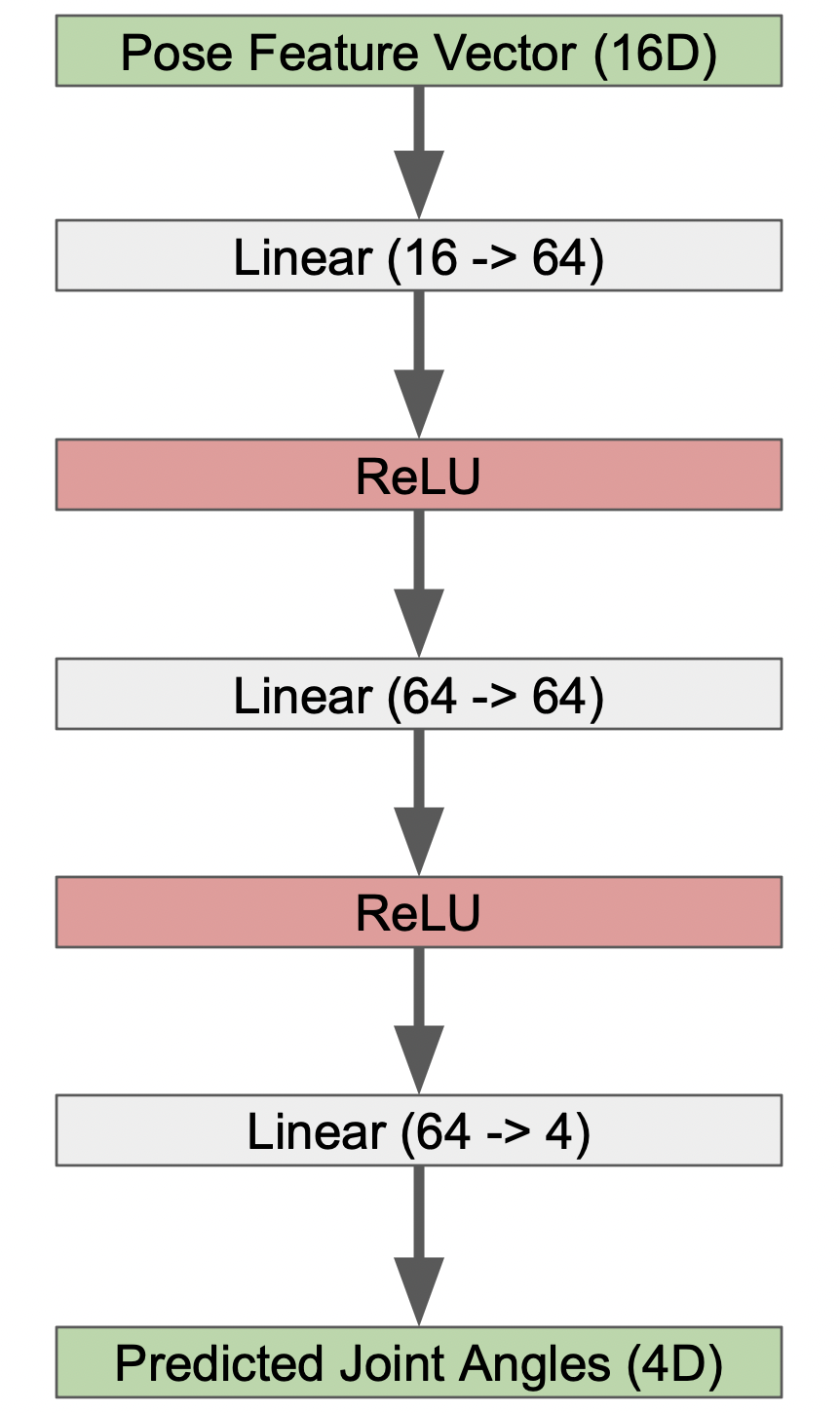

Model Architecture

To model the mapping from pose features to joint angles, we use a simple multilayer perceptron (MLP). The model takes a 16-dimensional pose feature vector as input and outputs four joint angles corresponding to the left shoulder, left elbow, right shoulder, and right elbow.

An MLP is sufficient for this task because it is a low-dimensional regression problem. The emphasis of the project is on the overall pipeline rather than on large-scale model complexity. The network is trained using mean squared error (MSE) loss with a train/validation split, following standard practices discussed in class.

Fig 4. Simple MLP Model Architecture for Pose -> Joint Angle Prediction.

Results and Findings

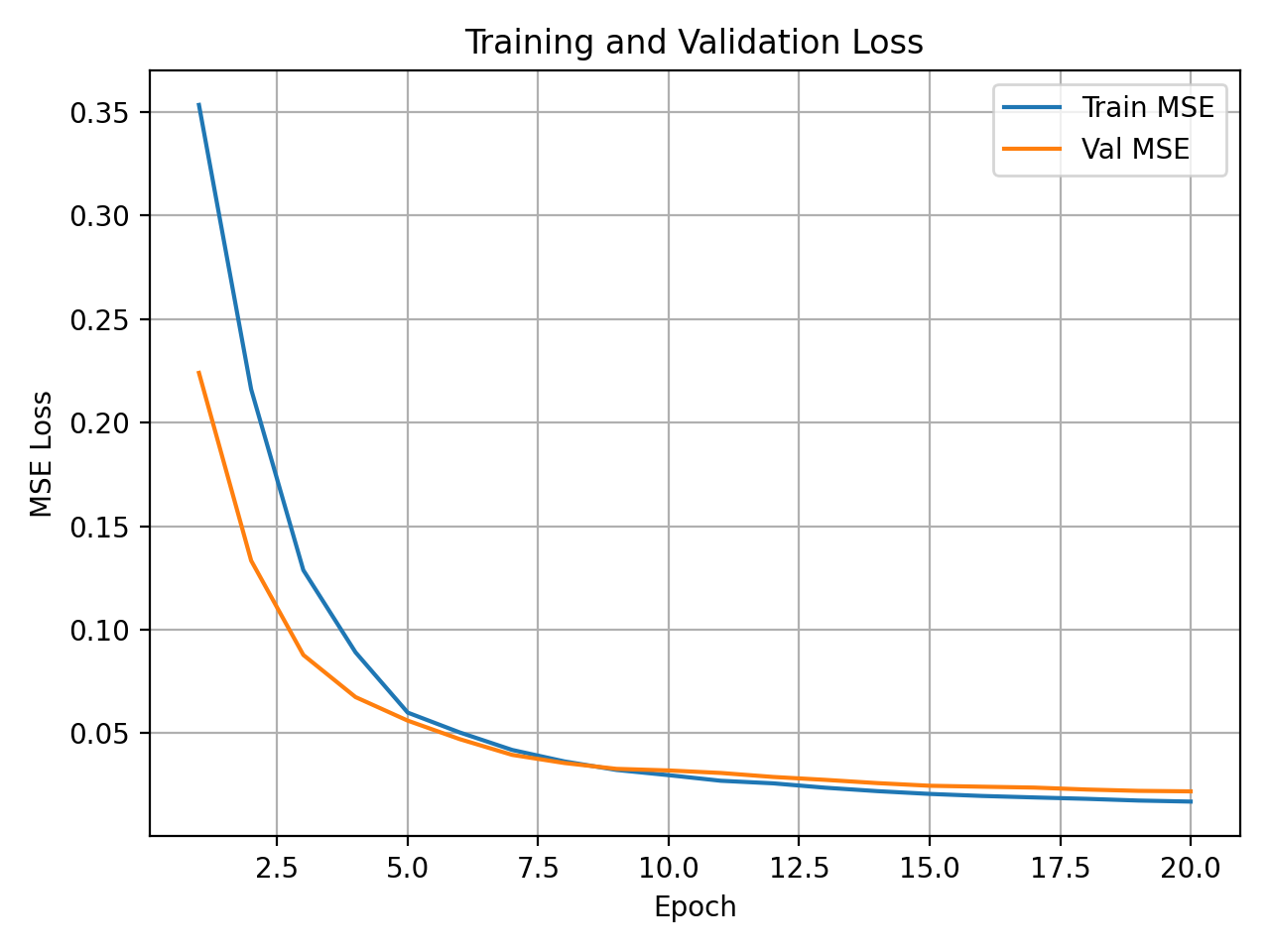

The trained model is able to predict plausible joint angles for a variety of upper-body poses. Qualitatively, when applied to real-time pose estimates from a webcam, the predicted angles produce robot motions that roughly match the observed human arm configurations.

To demonstrate model results, here are the training and validation loss curves:

Fig 5. Training and Validation Loss Curves for Joint Angle Prediction Model.

However, the predictions are not perfectly accurate. Errors arise due to the ambiguity of 2D pose representations, noise in keypoint detection, and the absence of temporal modeling. Additionally, differences between poses extracted from COCO images and poses observed in real-time video limit generalization. Despite these limitations, the model demonstrates that learning a pose-to-angle mapping from 2D keypoints is feasible and produces reasonable results.

Further Discussion

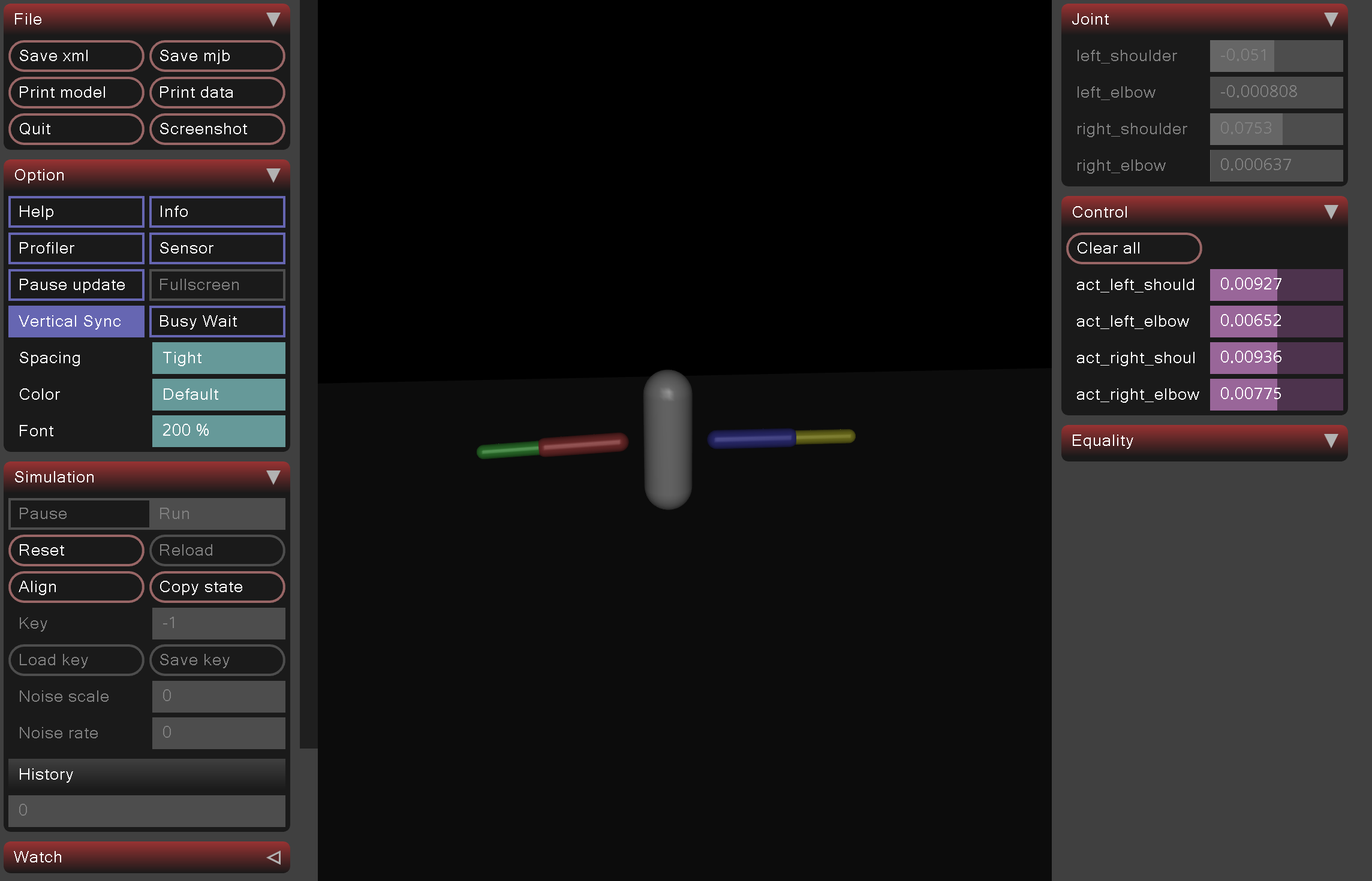

Beyond running existing codebases, we extend the pipeline by mapping predicted joint angles into a simulated robot environment using MuJoCo. This allows for visualization of how human pose predictions translate into robotic motion and highlights challenges such as joint constraints and physical plausibility.

Several potential extensions could further improve performance. Incorporating temporal models such as recurrent networks could smooth predictions across frames. Using 3D pose datasets or depth information could reduce ambiguity in joint angle estimation. Finally, deploying the pipeline on real robot hardware would provide a more realistic evaluation of pose-based control.

Fig 6. Example of MuJoCo Robot Simulation for Arms [3].

Conclusion

In this project, we explored how human pose estimation can be extended beyond visual understanding and applied to robotic motion. By leveraging a pretrained pose estimator, designing a normalized pose representation, and training a lightweight regression model, we demonstrated a complete pipeline that maps 2D human poses to robot joint angles. The resulting system is capable of producing plausible robotic motion from visual observations and highlights the potential of pose estimation as an interface between perception and control.

While the scope of this work is limited, the results illustrate the feasibility of learning pose-to-angle mappings using simple models and standard datasets. With additional time and resources, this approach could be extended through temporal modeling, 3D pose representations, or deployment on physical robot platforms. Overall, this project serves as a proof of concept for integrating computer vision techniques with robotic control and suggests several promising directions for future work.

References

[1] Tsung-Yi Lin, Michael Maire, Serge Belongie, Lubomir Bourdev, Ross Girshick, James Hays, Pietro Perona, Deva Ramanan, C. Lawrence Zitnick, and Piotr Dollár, “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context,” arXiv:1405.0312, 2014.

[2] J. Y. Choi, E. Ha, M. Son, J. H. Jeon, and J. W. Kim, “Human joint angle estimation using deep learning-based three-dimensional human pose estimation for application in a real environment,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 12, p. 3823, 2024, doi:10.3390/s24123823.

[3] Emanuel Todorov, Tom Erez, and Yuval Tassa, “MuJoCo: A physics engine for model-based control,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2012, pp. 5026–5033, doi:10.1109/IROS.2012.6386109.

[4] Valentin Bazarevsky, Ivan Grishchenko, Karthik Raveendran, Tyler Zhu, Fan Zhang, and Matthias Grundmann, “BlazePose: On-device real-time body pose tracking,” arXiv:2006.10204, 2020.