Machine Learning for Studio Photo Retouching: Object Removal, Background Inpainting, and Lighting/Shadow Preservation

Studio photography aims to produce aesthetically polished images. However, even in controlled environments, unwanted objects such as chairs, props, wires, etc., often appear in the scene. Further, lighting is altered tremendously by the addition / removal of these objetcs. Traditionally, these objects have been removed manually, requiring careful reconstruction of the background and its lighting conditions. This paper looks at modern models aimed at making this process easier.

- Introduction

- Background and Key Concepts

- Inpainting and Object Removal Methods

- Shadow and Lighting-Aware Editing

- Models for Controlled Editing

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Studio photography aims to produce aesthetically polished images. However, even in controlled environments, unwanted objects such as chairs, props, wires etc often appear in the scene. Traditionally, these objects have been removed manually, requiring careful reconstruction of the background and its lighting conditions. Although precise, manual editing is slow and labor-intensive.

Recent advancements in Machine Learning (ML) have opened new possibilities for automating this process. Given an image, the object being removed, and potentially other helpful information such as shadow location and the environment, ML models are tasked with outputting a natural looking image without the object and corresponding shadow. In this report, we discuss the different approaches ML models take in achieving this goal and their respective advantages and drawbacks.

Background and Key Concepts

The automation of advanced image editing requires a convergence of several computer vision disciplines, moving beyond simple pixel manipulation to semantic scene understanding. As studio workflows demand increasing speed and precision, the ability to algorithmically modify images, specifically removing objects and their environmental effects, has become a focal point of research. This section outlines the fundamental concepts underpinning these technologies, identifying the specific challenges associated with reconstructing visual data and the high-level strategies currently employed to solve them.

Image Inpainting is the process of reconstructing missing or corrupted regions of an image to restore its visual continuity. Early techniques relied on patch-based synthesis, which filled holes by copying and pasting similar textures from the surrounding valid pixels. While effective for simple, repetitive backgrounds, these methods often fail to preserve global structure or semantic coherence in complex scenes. Modern approaches utilize deep generative models, such as Generative Adversarial Networks and diffusion models, to “hallucinate” plausible content based on learned distributions. The primary challenge in a professional context is not merely filling the void, but generating high frequency details such as film grain or surface texture that match the fidelity of the original high resolution capture.

Shadow Detection and Removal presents a distinct set of challenges, as shadows are not objects themselves but rather the result of complex interactions between scene geometry and illumination. In studio photography, removing an object without addressing its cast shadow results in “ghosting artifacts” that immediately destroy the realism of the edit. Unlike opaque objects, shadows are semi-transparent. They darken the background without obscuring the underlying texture. Successfully removing a shadow requires the model to distinguish between illumination changes and intrinsic surface properties, a process often complicated by soft penumbras, inter-reflections, and colored lighting common in commercial sets.

General Strategies for addressing these tasks broadly fall into two categories: end-to-end learning frameworks and physics-based decomposition methods. Learning-based strategies leverage massive datasets of paired images, both with and without objects, to implicitly learn the correlation between foregrounds and backgrounds, treating the problem as a high-dimensional signal translation task. Conversely, physics-based approaches attempt to explicitly model the scene’s lighting and geometry, often decomposing the image into reflectance and shading layers to surgically modify the illumination. While recent trends favor the generative flexibility of the former, the structural consistency of the latter remains relevant. The specific architectures and performance trade-offs of these competing methodologies are detailed in the subsequent sections.

Inpainting and Object Removal Methods

Resolution-Robust Large Mask Inpainting with Fourier Convolutions

Large-mask inpainting is an inherently difficult problem because traditional convolutional neural networks lack a sufficiently large receptive field to capture global structures. When large regions of an image are missing (such as after removing a studio light stand or a softbox) the model must infer global texture patterns, geometry, and long-range spatial relationships. Classical and GAN-based inpainting models tend to produce blurry or repetitive textures, and they often break structural continuity across big holes. LaMa targets this limitation by introducing a method that enables global context aggregation early in the network while remaining robust across varying image resolutions, without requiring extremely deep or computationally expensive networks (since it is trained with low resolution images).

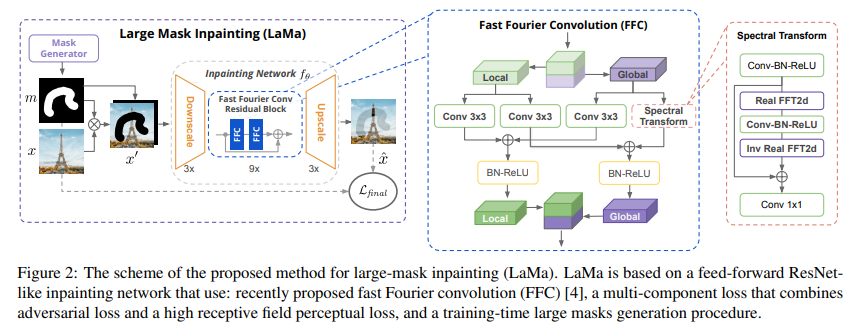

LaMa architecture

LaMa is built around a feed-forward ResNet-like inpainting network that integrates Fast Fourier Convolutions (FFCs) into its residual blocks. FFCs split feature channels into a local branch that uses standard spatial convolutions, and a global branch that applies real-valued FFT, performs spectral-domain convolution, and returns to spatial domain via inverse FFT. This allows the generator to achieve an image-wide receptive field even in early layers, addressing the limitations of conventional convolutional models. The architecture includes downsampling blocks, multiple FFC-based residual blocks, and upsampling blocks. The paper also incorporates adversarial loss, a high receptive field perceptual loss, and a feature-matching loss as part of its training objective. Specifically, LaMa uses a patch-level discriminator, an R1 gradient penalty, and discriminator-based perceptual loss, in addition to the proposed high receptive field perceptual loss. Training uses aggressive large-mask generation strategies, including wide and box masks, to force the model to utilize its large receptive field. All training is fully convolutional, and the network processes four-channel inputs consisting of the masked image and mask.

The paper introduces three major contributions. First, it proposes an inpainting network based on FFCs, which provide an image-wide receptive field and allow the model to use global context from early layers. The authors show that this improves perceptual quality, helps capture periodic structures, and supports generalization to higher resolutions. Second, LaMa introduces a high receptive field perceptual loss, built on a segmentation model with dilated or Fourier convolutions, ensuring that the loss function, just as the network itself, has the large receptive field required for global structure reasoning. This loss was shown in ablation studies to be important for the large-mask setting. Third, the authors develop an aggressive large-mask training strategy using wide and box masks. The paper demonstrates that this strategy improves performance on both wide and narrow masks, unlocking the benefits of the architecture and loss design.

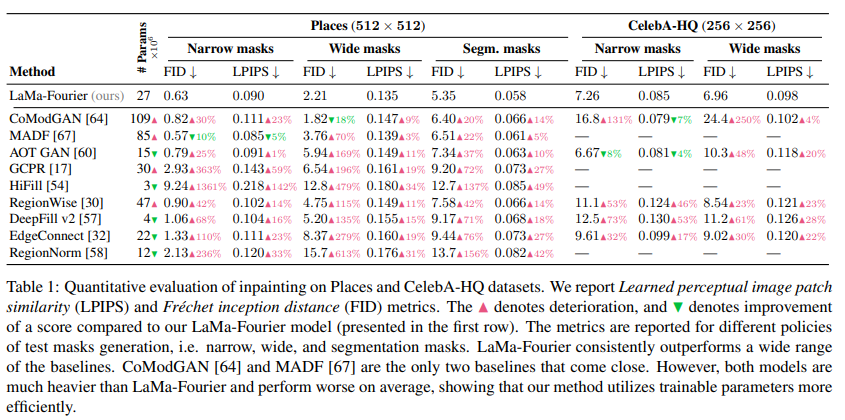

Quantitative results of LaMa vs other methods

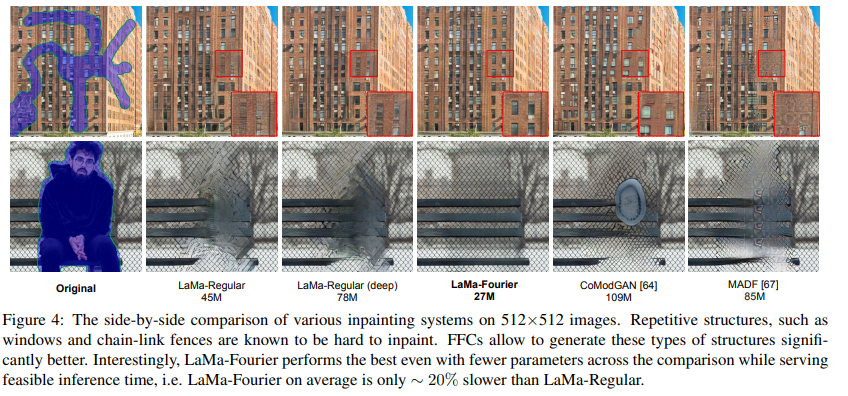

LaMa achieves state-of-the-art quantitative results across datasets such as Places and CelebA-HQ, outperforming a wide range of strong baselines on both narrow and wide masks. The FFC-based model consistently shows better FID and LPIPS scores than competing methods, including those with significantly larger parameter counts. Qualitative results in the paper demonstrate that LaMa can reconstruct complex periodic structures such as windows, fences, and bricks much more effectively than prior methods. The model also shows strong generalization to high-resolution images, despite being trained only on 256×256 crops. Experiments applying the network fully convolutionally to 512×512 and 1536×1536 images reveal that FFC-based models degrade much less than regular convolutional ones as resolution increases. Ablation studies also confirm the effectiveness of each proposed component: FFCs improve wide-mask inpainting, the high receptive field perceptual loss enhances global structure consistency, and large-mask training boosts performance across mask types.

Qualitative results of LaMa vs other methods

LaMa is ideal for removing large objects in studio scenes, such as light stands, cables, reflectors, tripods, or background supports. Its ability to reconstruct smooth backdrops or wide studio walls makes it especially practical for indoor photography. However, because it does not explicitly model lighting or shadows, LaMa does not remove shadow artifacts as effectively as newer methods. For studio workflows, LaMa is best as a baseline inpainting stage that fills structural background regions, followed by lighting-aware refinement if shadows must be preserved or reconstructed.

Smart Eraser

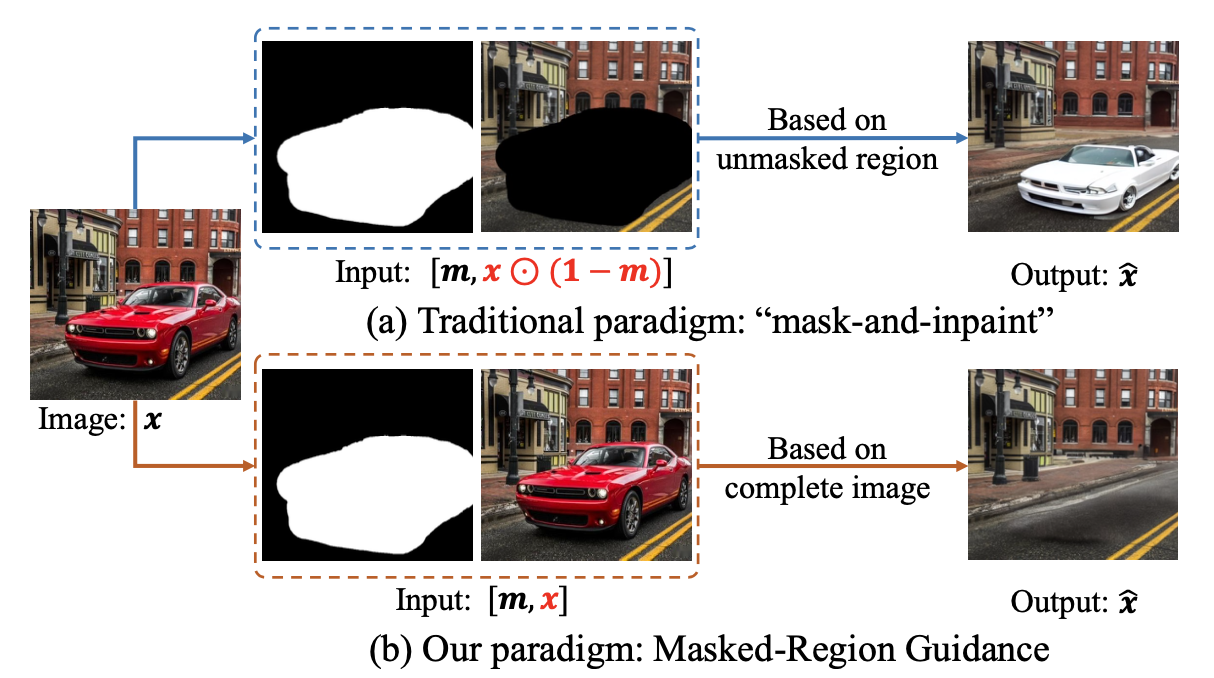

The SmartEraser addresses the structural limitations of the prevailing mask-and-inpaint paradigm used by most diffusion based object removal tools. In traditional approaches, the masked region is entirely excluded from the input, forcing the model to hallucinate missing content using only the surrounding unmasked context. This lack of visibility into the removed object often produces two characteristic artifacts: object regeneration (example: generating a new car instead of removing the old one) and background distortion (failing to preserve the continuity of the underlying scene).

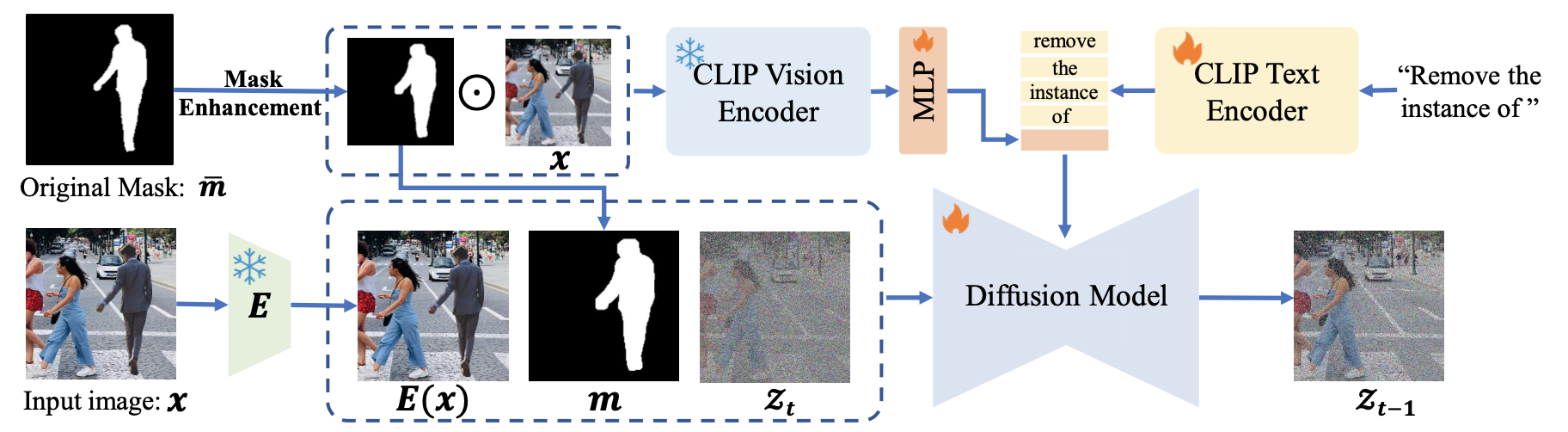

The SmartEraser is built on a text-to-image diffusion model but fundamentally modifies the conditioning mechanism through a paradigm called Masked-Region Guidance. Rather than supplying the model with a masked-out image, it retains the original image information in the input, represented as [m, x] instead of [m x ⊙ (1−m)].

Comparison of the "mask-and-inpaint" paradigm versus the proposed Masked-Region Guidance paradigm. Unlike the traditional approach, Masked-Region Guidance retains the masked region in the input to better identify removal targets

This allows the model to explicitly perceive the semantic content of the target object. To strengthen this semantic awareness, SmartEraser incorporates CLIP-based visual guidance where the masked region is cropped and fed into a CLIP vision encoder, and a trainable MLP maps these features into the text encoder’s space. This representation is then combined with the prompt “Remove the instance of …” to guide the diffusion process.

To address inaccuracies in user-provided masks, SmartEraser introduces a Mask Enhancement module during training. This module simulates mask perturbations (dilation, erosion, and convex hull transformations) to reduce the gap between highly precise training masks and imperfect real-world user inputs.

The overall framework of SmartEraser, illustrating the integration of Mask Enhancement and CLIP-based visual guidance with the diffusion model

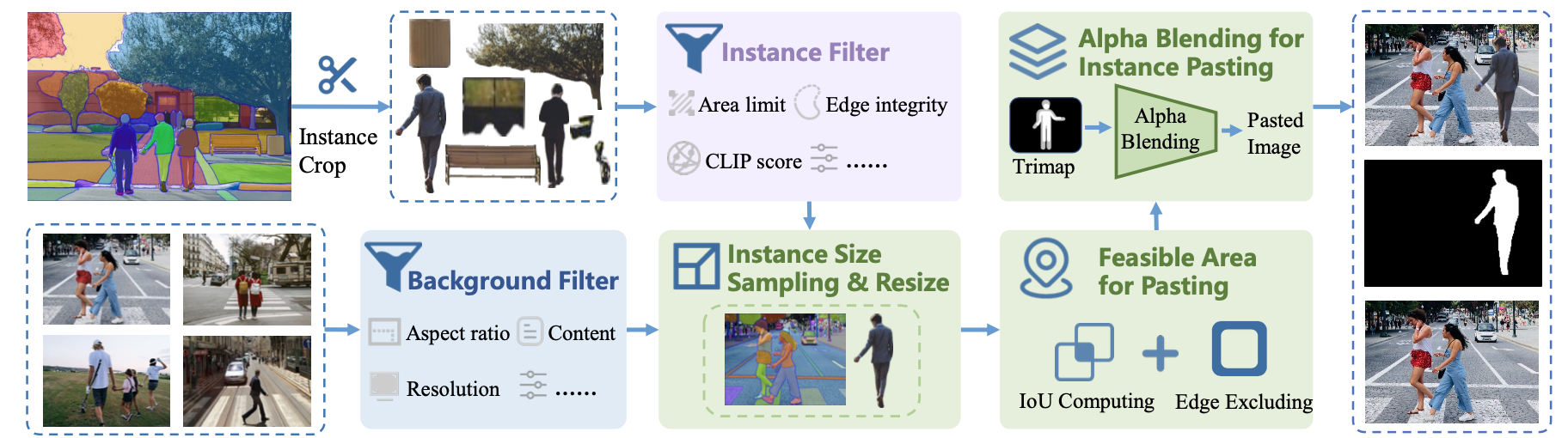

Beyond its architectural contributions, the paper’s primary innovation is Syn4Removal, a large-scale synthetic dataset designed to overcome the scarcity of paired training data. Existing datasets typically lack scene diversity or rely on pseudo-ground truths generated by other inpainting models. Syn4Removal instead uses a high quality copy/paste synthesis pipeline where objects are segmented from source images and alpha-blended onto diverse backgrounds.

The data generation pipeline for Syn4Removal. Object instances are filtered, resized, and alpha-blended onto background images to create training triplets

Importantly, objects are pasted only into feasible areas (regions that do not overlap with existing scene elements), ensuring that the ground truth (the empty background) remains an unaltered photograph.

The SmartEraser was evaluated against state-of-the-art baselines including LaMa, PowerPaint, and CLIPAway on the RORD-Val and DEFACTO-Val benchmarks. Quantitatively, it outperformed all baselines, surpassing PowerPaint by 10.3 FID points on the challenging RORD-Val dataset. Qualitative comparisons and user studies further show that SmartEraser effectively avoids regeneration artifacts and preserves background realism.

For studio photo retouching, SmartEraser is specifically well-suited to removing props and distractions. The Masked-Region Guidance approach ensures that the model removes specific items (such as light stands, cables, product supports) without hallucinating new content in their place. Additionally, the Syn4Removal methodology provides a blueprint for generating domain specific training triplets where studios can paste their own products onto blank studio backgrounds to create unlimited fine-tuning data tailored to their lighting setups.

OmniEraser

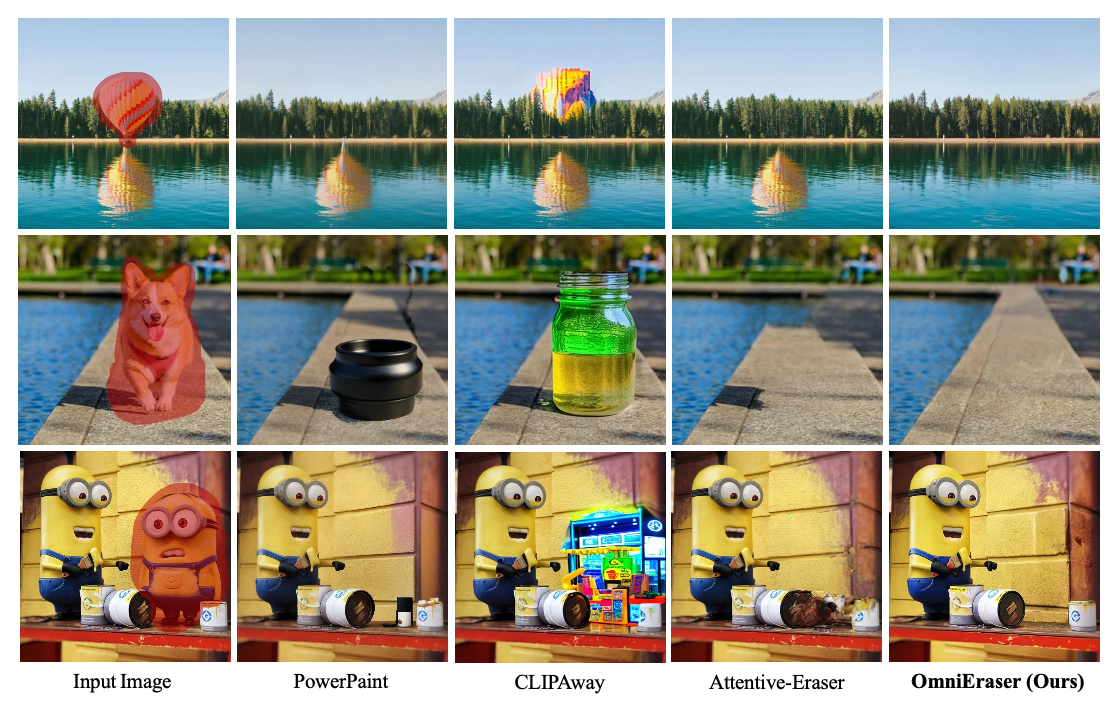

The OmniEraser addresses a persistent challenge in high-end image editing which is removing an object along with its associated visual effects, specifically shadows and reflections. While standard inpainting models often succeed in removing the object itself, they frequently leave behind cast shadows or floor reflections, resulting in “ghost” artifacts that break realism.

Comparison of OmniEraser against state-of-the-art methods. OmniEraser successfully removes objects along with their shadows and reflections, whereas other methods leave artifacts or generate unintended objects

Additionally, many existing methods produce shape-like distortions in the edited region because they rely exclusively on background information without explicit modeling of object geometry.

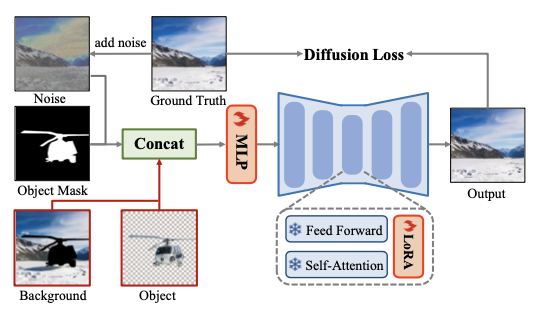

The OmniEraser builds upon the FLUX.1-dev diffusion model, a DiT-based Transformer architecture, augmented with LoRA for efficient fine-tuning. Its central innovation is Object-Background Guidance, a dual-path conditioning framework. Instead of treating the image as a single unified input, the model processes the foreground object and the background as independent guidance signals during the denoising process. The hidden representations of the masked object, masked background, noise input, and mask are concatenated and passed through a trainable linear layer.

Architecture of OmniEraser featuring Object-Background Guidance. The model uses latent representations from both the object and background as joint input conditions

This conditioning forces the model to learn the relationship between the object and its environment which allows for the accurate removal of both the object and its lighting effects.

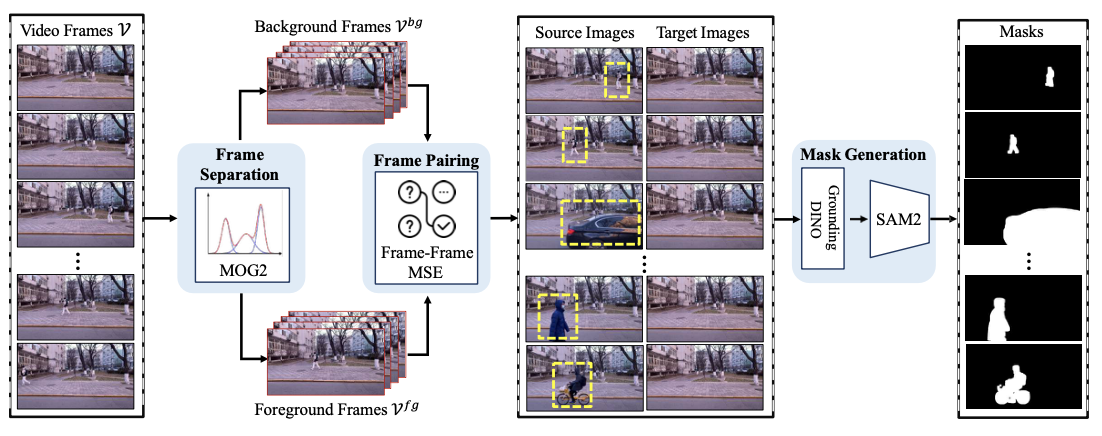

To support this capability, the authors introduce Video4Removal, a large-scale dataset built from real-world video footage rather than synthetic compositing. Unlike synthetic datasets such as Syn4Removal (which cannot realistically capture shadows or reflections), Video4Removal uses fixed-camera videos of scenes with and without moving subjects. Foreground and background frames are separated using the Mixture of Gaussians (MOG) algorithm, producing over 100,000 high-quality triplets that naturally include real shadows, lighting variations, and reflections (visual phenomena that are extremely difficult to synthesize).

The construction pipeline of Video4Removal. Foreground and background frames are separated from video footage to create realistic training pairs with natural lighting effects

The OmniEraser was benchmarked on RORD-Val and on a newly proposed dataset, RemovalBench, constructed specifically to evaluate shadow and reflection removal. Quantitative results show state-of-the-art performance: for example, OmniEraser achieves an FID of 39.52, outperforming CLIPAway’s 55.49 on RemovalBench. Visual comparisons highlight its ability to seamlessly remove complex shadows and reflections on glossy surfaces which is an area where competing models consistently fail or hallucinate unrealistic textures.

The OmniEraser is especially impactful for lighting-aware studio retouching. Studio photography relies heavily on controlled lighting that produces intentional shadows and reflections, which are notoriously difficult to remove manually. OmniEraser’s ability to eliminate both an object and its cast shadow in a single pass directly addresses a major bottleneck in e-commerce and catalog workflows. Moreover, the Video4Removal pipeline generalizes naturally to studio setups: studios can generate perfect datasets by recording their sets before and during a shoot, capturing the exact lighting behavior required for training

Shadow and Lighting-Aware Editing

Removing Objects and Their Shadows Using Approximate Lighting and Geometry

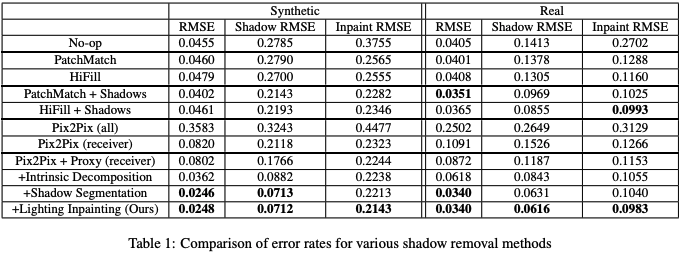

Traditional inpainting only cares about the object itself, not the shadows. As such, the left over shadows look out of place. Methods such as HiFill[1] and DeepFill[2] that take shadows into account still require specifying shadow regions. Shadows also vary a lot in hardness, subtext, so approaches relying on hard boundaries as seen in [3] do not work well.

Differential rendering is a classical technique that attempts to solve this problem by building a rough 3D proxy of the scene, rendering it before and after an edit, and then applying the pixelwise difference between the two renders to the real image. While this should in theory encode how shadows should change, scene proxies are almost always inaccurate. A more robust method is needed to identify and remove only the object’s shadows.

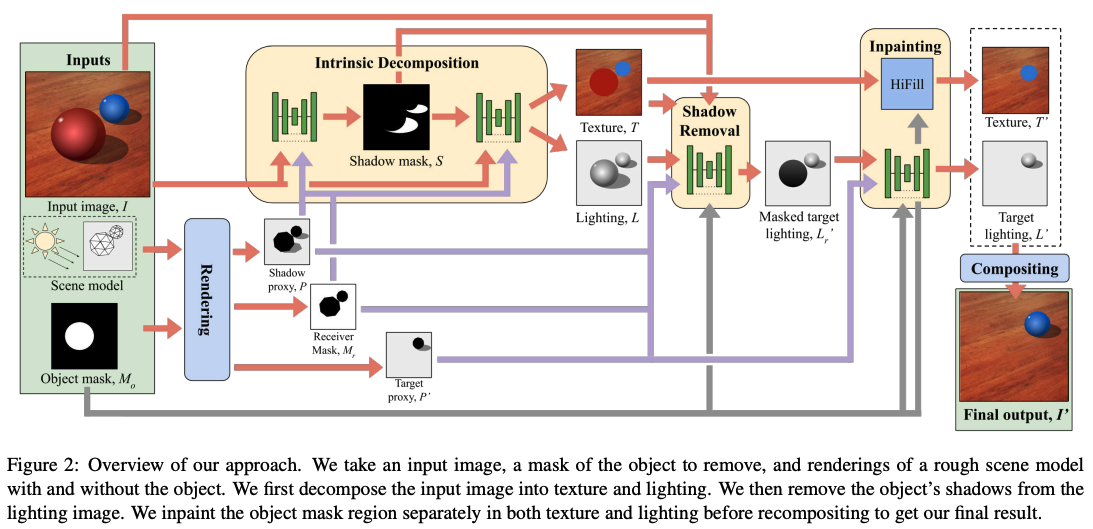

Model architecture. It takes an input image, a mask of the object to remove, and renderings of a rough scene model with and without the object. It first decomposes the input image into texture and lighting. It then removes the object’s shadows from the lighting image. It inpaints the object mask region separately in both texture and lighting before recompositing to get the final result.

The architecture consists of multiple neural networks (U-Nets). The shadow segmentation network learns to indicate where shadows exist. The intrinsic decomposition network splits the image into two - texture and lighting. The shadow removal network removes the shadow cast only by the object removed. The inpainting later fills in lighting behind the removed object. An HFill texture inpainting tool is used to inpaint reflectance. Lastly, the final compost layer recombines the texture and lighting to the final output.

Previous methods either ignored shadows or relied on a manually drawn shadow mask. This paper removes shadows automatically. Furthermore, this method works even with an inaccurate proxy because of its intrinsic decomposition. Shadows of other objects remain intact.

Architecture of OmniEraser featuring Object-Background Guidance. The model uses latent representations from both the object and background as joint input conditions

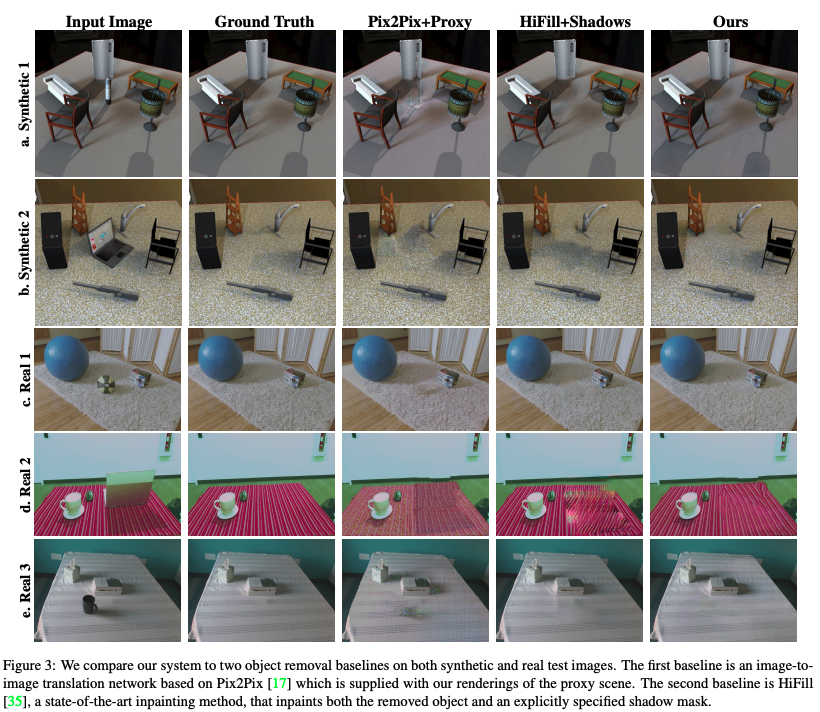

This paper’s method achieves the lowest Shadow RMSE on both synthetic and real datasets. It does much better than the Pix2Pix and HiFill baselines. Its improvements can be seen when compared to other methods - it consistently removes shadows and objects in a way that best matches the ground truth. It handles multiple lights, complex shadows, and removes both the object and shadow. Trained over a large dataset, it is robust and trustworthy.

The system is compared to two object removal baselines on both synthetic and real test images. The first baseline is an image-to-image translation network based on Pix2Pix [8], which is supplied with renderings of the proxy scene. The second baseline is HiFill [5], a state-of-the-art inpainting method that inpaints both the removed object and an explicitly specified shadow mask

Models for Controlled Editing

DreamPainter

DreamPainter is designed to address two challenges in e-commerce background generation. First, existing inpainting methods struggle to maintain product consistency, including proper spatial arrangement, coherent shadows, and realistic reflections between the foreground and the generated background. The paper attributes this to the lack of high-quality, domain-specific e-commerce datasets, noting that models trained on generic data often produce inconsistent lighting, low-resolution backgrounds, or stylistically mismatched imagery. Second, the authors emphasize that relying solely on text prompts is not enough for controlling background generation in professional settings. Text descriptions cannot always express visual attributes such as color gradients, material textures, or stylistic preferences. This issue becomes worse when creators seek to translate abstract design concepts into precise visual outputs.

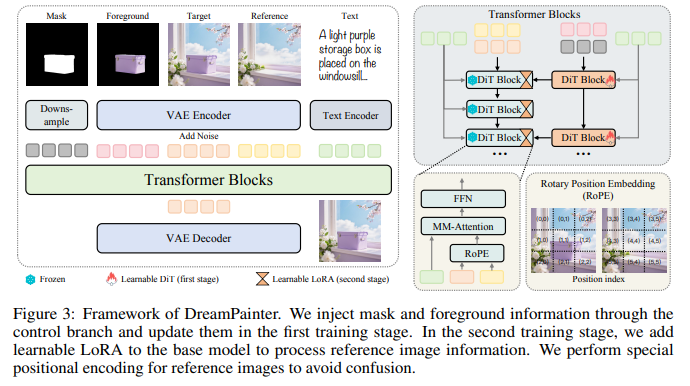

Architecture of DreamPainter

DreamPainter transforms a text-to-image diffusion model into a background inpainting model by incorporating both textual and visual conditioning signals. The system takes as input the foreground image, mask, target image, and optional background reference image, and encodes each using a VAE into corresponding latent representations. These latents, along with text prompt embeddings and a downsampled mask, are fed into a diffusion transformer architecture (DiT) through two conditioning strategies.

The first strategy uses input-layer channel concatenation, where the model concatenates latent tensors along the channel and spatial dimensions and feeds them into the first layer. The second strategy, which the authors adopt, introduces an auxiliary control branch that processes the mask, foreground, and noisy target latents. The output of this branch is injected into each diffusion layer through a learnable gate initialized to zero. This design builds off prior findings that additional control branches can improve training stability and efficiency.

Reference images are incorporated by concatenating reference latents with target and text tokens along the spatial dimension and assigning distinct positional encodings. By giving the reference tokens separate positional indices, the model avoids confusion between the target and reference spatial structures. In the second stage of training, LoRA modules are added to the DiT blocks to adapt the base model to reference-guided generation while keeping earlier components frozen. Together, these mechanisms enable DreamPainter to accept text-only control, text-plus-reference control, and user-adjustable reference influence.

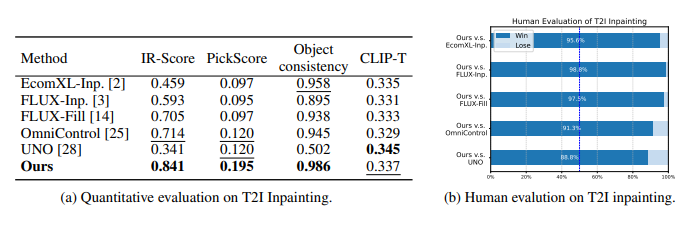

Quantitative results

The paper reports extensive quantitative and qualitative evaluations of DreamPainter on text-to-image (T2I) and text-and-reference-to-image (TR2I) inpainting tasks. On T2I background inpainting, DreamPainter significantly outperforms state-of-the-art baselines such as EcomXL-Inpainting, FLUX-Inpainting, FLUX-Fill, OmniControl, and UNO. The model achieves the highest scores across IR-Score, PickScore, and Object Consistency, with the latter reaching 0.986, indicating minimal distortion of foreground objects. Human evaluators overwhelmingly prefer DreamPainter’s results, with win rates exceeding 90% against all baselines.

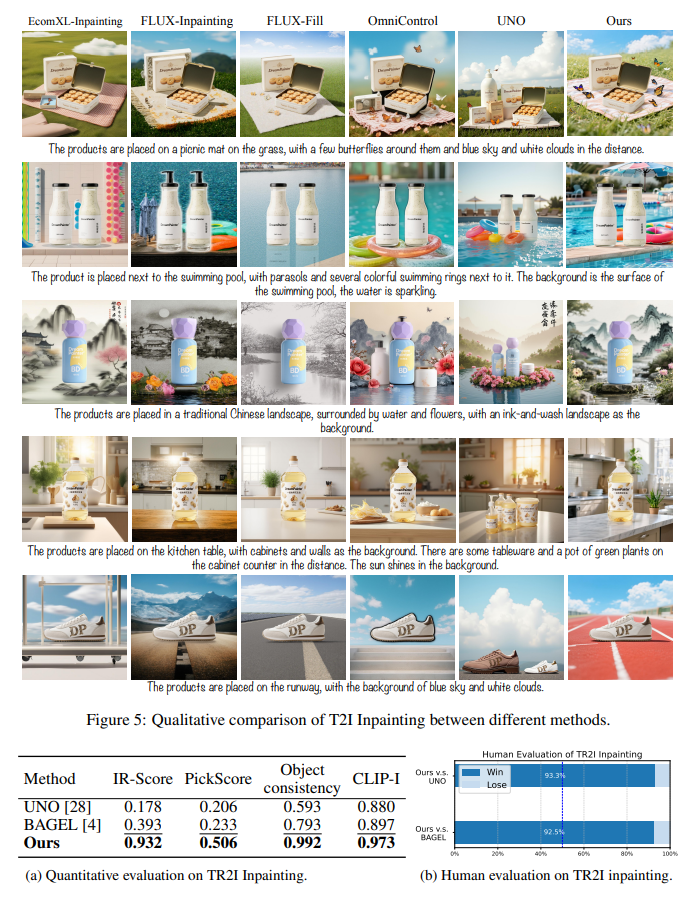

Qualitative results / comparions

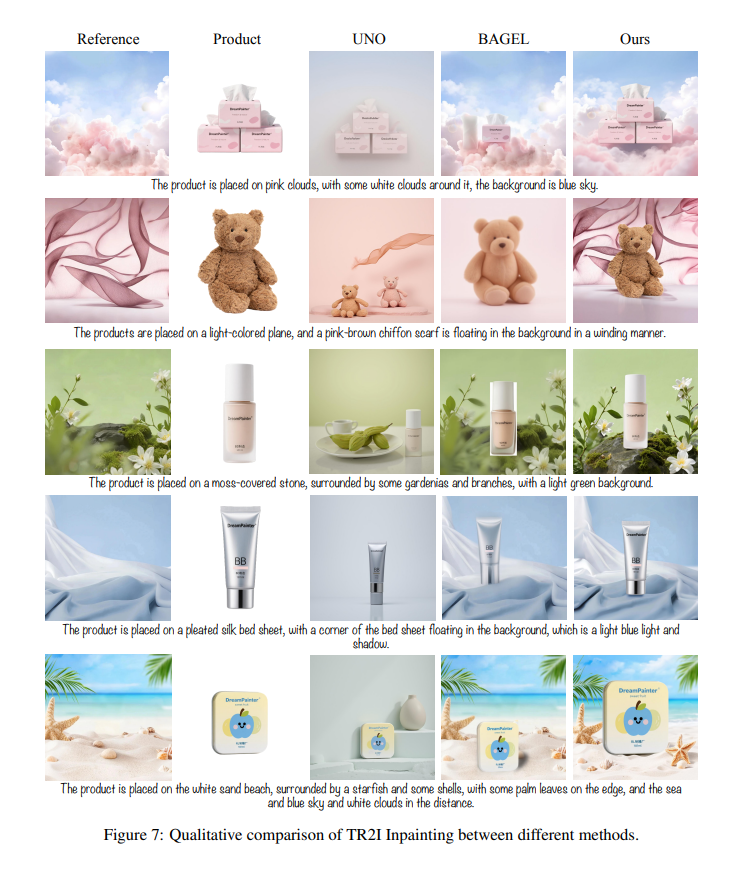

On TR2I inpainting, DreamPainter demonstrates even larger performance gains. It surpasses multi-image editing methods like UNO and BAGEL across all quantitative metrics, achieving a 137% improvement over the second-best method in IR-Score and a 125% improvement in PickScore. Object Consistency and CLIP-based semantic alignment also show substantial gains. Human evaluation again supports these findings, with DreamPainter winning over 92% of comparison pairs. Qualitative examples in the text and figures show that DreamPainter preserves product fidelity while producing coherent, stylized, and contextually appropriate backgrounds.

Qualitative results / comparions

Although designed for product photography, DreamPainter is highly relevant to studio retouching because it demonstrates the power of multi-modal control in background editing. A studio editor could mask out a light stand, supply a clean reference background from the same shoot, or describe the desired fill via text. DreamPainter’s ability to harmonize lighting across the edited region aligns closely with professional studio needs, where shadows, reflections, and background gradients must remain consistent. Its multi-control architecture also suggests how future studio-retouching tools may combine mask guidance, lighting cues, and reference photos for fully controllable ML-driven editing.

ScribbleLight

ScribbleLight addresses the significant challenge of single-image indoor relighting, a task complicated by the presence of multiple light sources, cluttered objects, and intricate material variations. Previous methods often relied on dense scene capture, which is labor-intensive, or implicit latent representations that offer only coarse, global control over illumination. To bridge the gap between technical complexity and creative flexibility, ScribbleLight introduces a generative framework that allows users to manipulate lighting locally—such as turning lamps on or off, or adjusting sunlight—using intuitive, sparse scribbles. This approach treats user input as binary guidance, where scribbles indicate areas to brighten or darken, leaving the model to infer plausible physical interactions like soft shadows and inter-reflections. The key advances, briefly mentioned here, are related to Intrinsic Image Decomposition, i.e. separating an image into illumination dependent and independent components. ScribbleLight uses components from both groups to achieve a realistic looking outcome; specifically, ScribbleLight uses Albedo, how reflective a surface is, and normals, a representation of the 3d map of the image in combination with the image itself to generate a realistic looking output.

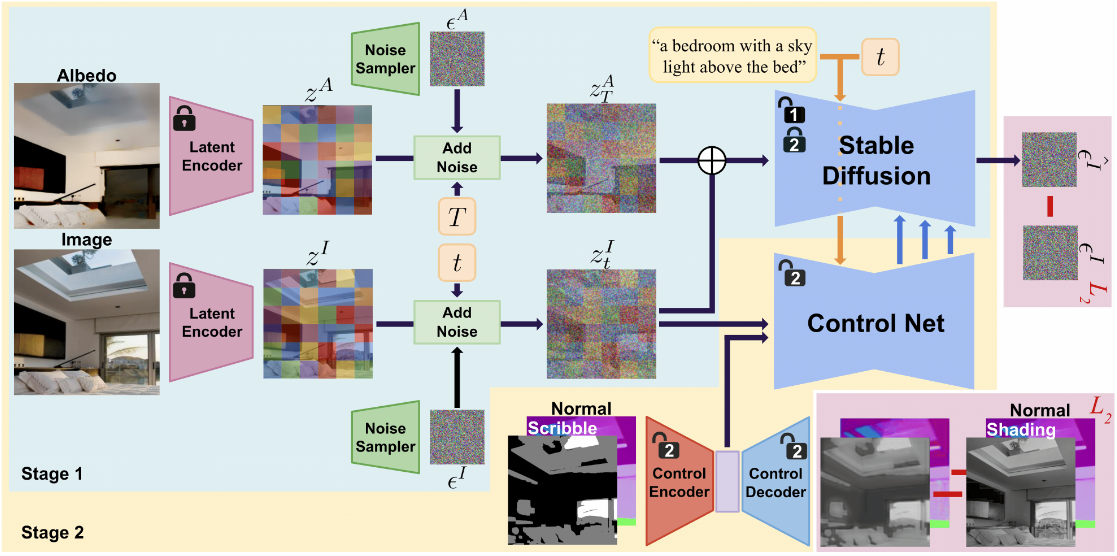

ScribbleLight works in a multi-stage process with stage 1 containing an Albedo-conditioned Stable image Diffusion model and stage 2 containing a ControlNet that guides the albedo model.

The core of the model is a modified Stable Diffusion v2 framework, divided into two training stages. The first stage contains an Albedo-conditioned Stable image Diffusion model. To preserve the intrinsic color and texture of the original scene, the model uses pre-trained Latent VAE Encoders to encode the image and albedo into the latent space. Then, noise for a random time sample from Stable Diffusion is added back into the latent space code. Image noise is randomly added while albedo noise is added from time step T = 200. Then, the albedo-conditioned model is trained with text prompt p with the following loss function

Loss function for the Stable Diffusion model

The second stage employs a ControlNet to guide the diffusion model using user scribbles and surface normal maps. Using a learnable Control Encoder, the normals and user scribbles are concatenated into a lighting feature map. Then, using the image latent code, text prompt p, and Stable Diffusion weights, the ControlNet is trained with the following loss function

Loss function for the ControlNet

To train the model, real indoor images from LSUN Bedrooms were used. After creating the albedo maps for each image, text prompts with BLIP-2, normals with DSINE, and shading with an IID, sample user scribbles are generated with the following criteria

User scribble criteria

With u and o as the mean and standard deviation of all pixels. Finally, an erosion and dilation with kernel sizes between 3 and 19 are performed to make the edges of the generated scribbles look more human.

The key advances of this implementation are that high - quality lighting effects are created from sparse inputs while respecting the “human”-like nature of images, i.e. the texture of objects in the room, the number of objects in the room, etc. Further, due to the use of Stable Diffusion, multiple replicas can be created from one input allowing users to select from multiple realistic images as to which one employed their scribbles in the best possible manner. Specifically, stage 1 using albedo + noise uncertainty ensures that the Stable Diffusion model has variation within its lit areas while preserving the key textures / objects / colors in the original image. Stage 2 using ControlNet allows for ScribbleLight to build up from the generated image and incorporate user scribbles effectively. The Decoder is then forced to reconstruct the normal map and shading from the light features from the encoder fed input; this forces the latent map to encapsulate 3d geometry rather than 2d patterns.

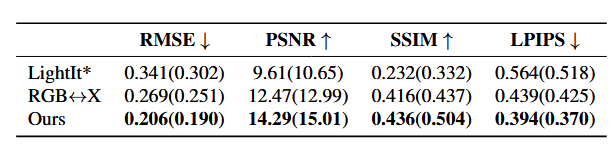

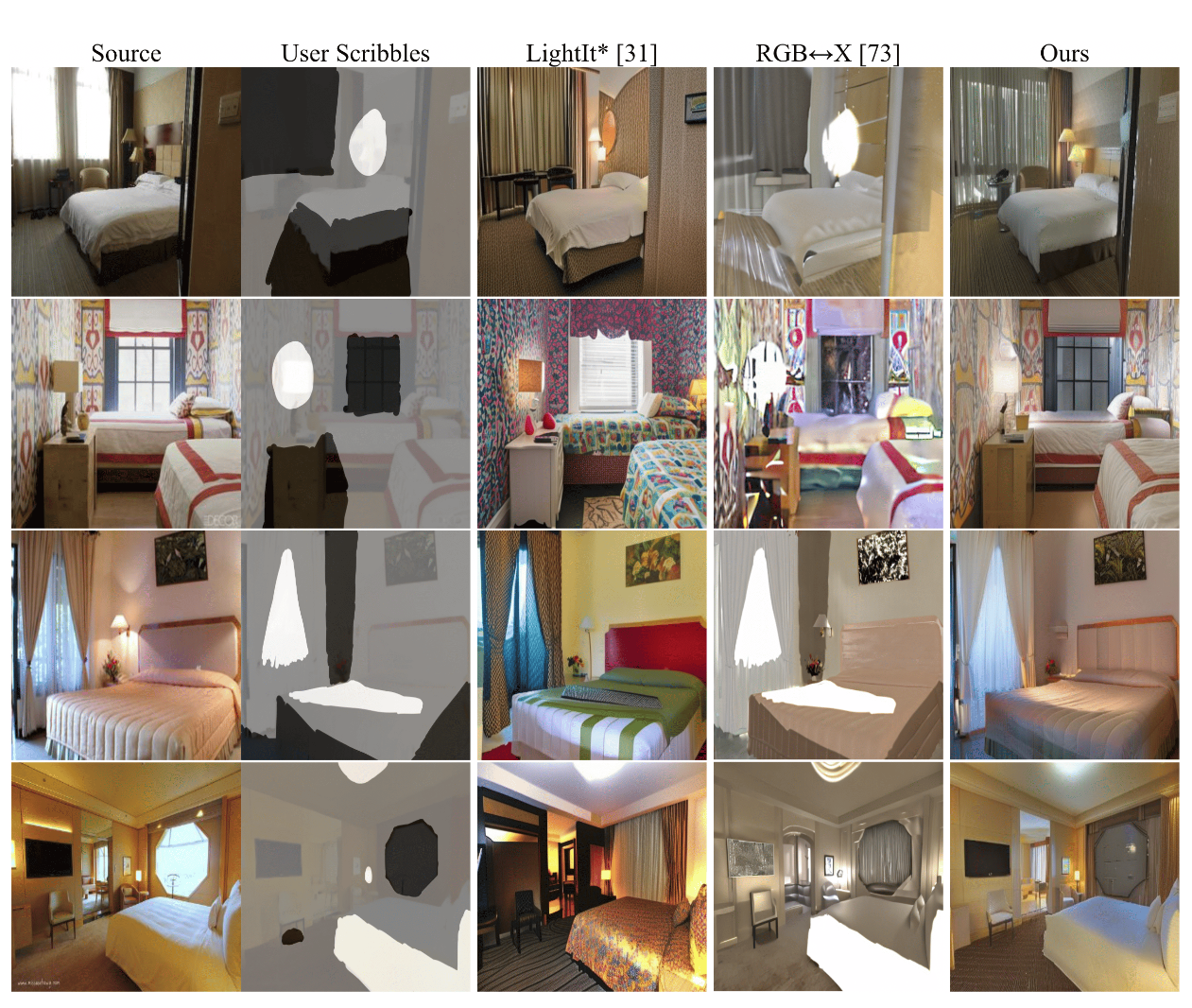

With the manually and auto-generated user scribbles on the LSUN Bedrooms images, ScribbleLight was tested against LightIt with the auto-generated scribble annotations and RGB<->x without retraining using normal, albedo, roughness, and metallicity components. Further, RMSE, PSNR, SSIM, and LPIPS were used to quantitatively test error. In order, these measure pixel by pixel similarity, amount of noise in the image, structure of neighborhoods on pixels, and feature difference in deep layers. Thus, low RMSE + high PSNR indicate good pixel similarity while high SSIM and low LPIPS indicate that generated images maintain structure and have good features.

Quantitative results of employing models on test images.

Qualitatively, ScribbleLight preserves the albedo of images and is able to generate plausible light / shadows considering light sources that are both in / out of images. Further, given a single image, ScribbleLight is able to iteratively generate better lighting and also based on different provided user scribbles create plausible scenarios. Finally, ablation testing by removing albedo noise, the control-decoder, and normals illustrated that each step in the pipeline contributed to meaningful improvements. Specifically, the albedo noise preserves the texture of the input image and the decoder/normals preserve the objects in the image.

Qualitative results of employing models on test images.

ScribbleLight fails to rectify inconsistencies with user-generated scribbles and plausible light sources in the image. Further, ScribbleLight is biased towards common light colors(i.e. White, blue). However, ScribbleLight preserves texture and color of input images better than any current models. The ability of ScribbleLight to generate multiple version is additionally extremely beneficial for users seeking to add lighting / shadow to their images and iterate over multiple versions without spending exorbitant amounts of time.

Discussion

The studied methods collectively reveal a clear trend toward ML editing systems that better reflect the constraints of studio photography. Instead of relying solely on generic inpainting, recent approaches increasingly account for large uniform backgrounds, controlled lighting, and complex interactions such as shadows and reflections. LaMa demonstrates how globally aware architectures can more effectively fill large missing regions common in studio object removal, while SmartEraser and OmniEraser show a shift toward models that preserve visibility into the removed object so the system can avoid regeneration artifacts and correctly handle lighting effects. The “No Shadow Left Behind: Removing Objects and Their Shadows Using Approximate Lighting and Geometry” paper contributes a complementary view by highlighting that even when object removal succeeds, the leftover shadows often break realism. Its use of shadow segmentation, intrinsic decomposition, and shadow removal networks reveals the need for explicit lighting modeling to handle multiple lights and complex shadow behavior. DreamPainter and ScribbleLight further highlight the growing use of richer conditioning signals such as text, reference images, masks, albedo, normals, and user scribbles in order to give editors more precise control than what traditional mask-only pipelines allow. These developments suggest a progression toward multimodal, lighting-aware, and context-sensitive editing tools designed specifically for studio-quality images.

At the same time, the methods highlight several persistent technical challenges. One difficulty is maintaining global structural consistency when large regions of an image are removed, a problem LaMa tackles through its use of large receptive fields. The shadow-removal paper demonstrates that shadows are particularly difficult because they depend on material, geometry, and multi-light interactions; inaccurate 3D proxies make classical methods unreliable. SmartEraser identifies the issue that models often hallucinate new objects or distort the background when they cannot see the removed region, while OmniEraser addresses the long-standing challenge that most methods struggle to eliminate shadows and reflections in a realistic way. DreamPainter points out that models trained on generic datasets often fail to maintain product fidelity or studio lighting consistency, and ScribbleLight illustrates the complexity of controlling lighting effects based on sparse user inputs while preserving fine texture and geometry. These issues show that both physical properties such as shadows, reflections, and illumination and global context remain difficult for current systems to accurately reconstruct.

Despite these challenges, the papers complement one another in ways that outline a promising multi-stage pipeline for studio editing. LaMa offers a strong foundation for filling background structure after object removal. SmartEraser extends this by preventing the regeneration of the object and ensuring the background remains coherent. The shadow-removal paper supplies a mechanism for identifying and eliminating shadows tied to the removed object. OmniEraser then adds the ability to remove shadows and reflections, which the earlier methods do not explicitly address. DreamPainter can then be used to generate or refine backgrounds with high stylistic or lighting consistency while preserving the foreground product. ScribbleLight provides fine-grained, user-controlled relighting to finalize the scene. Together, these models form a chain of capabilities that span structural reconstruction, semantic understanding, lighting-aware removal, background generation, and interactive lighting control.

Conclusion

Taken together, the reviewed methods outline substantial progress in ML-based studio photo editing but also reveal clear opportunities for future advancement. None of the current models provide a unified approach that removes objects, eliminates shadows, maintains global structure, generates consistent backgrounds, and offers precise user controlled lighting within a single system. The reliance on synthetic or video based datasets also highlights the difficulty of acquiring high-quality, studio specific training data, especially when realistic shadow behavior is required. DreamPainter demonstrates the advantages of domain specific datasets and multimodal conditioning, suggesting that future systems could incorporate reference lighting cues or per-shoot calibration images. ScribbleLight’s limitations with inconsistent scribbles and uncommon light colors, along with the fact that OmniEraser and LaMa do not explicitly model lighting geometry, point to further opportunities for integrating physical lighting reasoning with flexible user controls. Ultimately, these findings suggest a promising direction toward holistic, studio-aware editing models capable of unifying structural, semantic, and illumination related reasoning within a single end-to-end framework.

References

[1] R. Wei, Z. Yin, S. Zhang, L. Zhou, X. Wang, C. Ban, T. Cao, H. Sun, Z. He, K. Liang, and Z. Ma, “OmniEraser: Remove Objects and Their Effects in Images with Paired Video-Frame Data,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.07397, Mar. 2025.

[2] L. Jiang, Z. Wang, J. Bao, W. Zhou, D. Chen, L. Shi, D. Chen, and H. Li, “SmartEraser: Remove Anything from Images using Masked-Region Guidance,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.08279, Jun. 2025.

[3] S. Zhao, J. Cheng, Y. Wu, H. Xu, and S. Jiao, “DreamPainter: Image Background Inpainting for E-commerce Scenarios,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.02155, Aug. 2025.

[4] R. Suvorov, E. Logacheva, A. Mashikhin, A. Remizova, A. Ashukha, A. Silvestrov, N. Kong, H. Goka, K. Park, and V. Lempitsky, “Resolution-robust Large Mask Inpainting with Fourier Convolutions,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.07161, Sep. 2021.

[5] Z. Yi, Q. Tang, S. Azizi, D. Jang, and Z. Xu, “Contextual Residual Aggregation for Ultra High-Resolution Image Inpainting,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020.

[6] Y. Zeng, Z. Lin, J. Yang, J. Zhang, E. Shechtman, and H. Lu, “High-Resolution Image Inpainting with Iterative Confidence Feedback and Guided Upsampling,” in European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2020.

[7] T. Wang, X. Hu, Q. Wang, P.-A. Heng, and C.-W. Fu, “Instance Shadow Detection,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2020.

[8] P. Isola, J.-Y. Zhu, T. Zhou, and A. A. Efros, “Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks,” in IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017.

[9] J. M. Choi, A. Wang, P. Peers, A. Bhattad, and R. Sengupta, “ScribbleLight: Single Image Indoor Relighting with Scribbles,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.17696, Nov. 2024.

[10] N. Magar, A. Hertz, E. Tabellion, Y. Pritch, A. Rav-Acha, A. Shamir, and Y. Hoshen, “LightLab: Controlling Light Sources in Images with Diffusion Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.09608, May 2025.

[11] Z. Li, J. Shi, S. Bi, R. Zhu, K. Sunkavalli, M. Hašan, Z. Xu, R. Ramamoorthi, and M. Chandraker, “Physically-Based Editing of Indoor Scene Lighting from a Single Image,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.09343, May 2022.