Visuomotor Policy

Visuomotor Policy Learning studies how an agent can map high-dimensional visual observations (e.g., camera images) to motor commands in order to solve sequential decision-making tasks. In this project, we focus on settings motivated by autonomous driving and robotic manipulation, and survey modern learning-based approaches—primarily imitation learning (IL) and reinforcement learning (RL)—with an emphasis on methods that improve sample efficiency through policy/representation pretraining.

- Introduction

- Problem Setup

- Approaches

- Policy Pretraining

- Diffusion Policy

- 3D Diffusion Policy (DP3) [4]

- References

Introduction

Visuomotor policy learning aims to learn a control policy directly from visual inputs, enabling an agent to perceive its environment and take actions that accomplish a task. Compared with classical pipelines that rely on modular perception, planning, and control, end-to-end visuomotor learning offers a unified framework that can, in principle, learn task-relevant features automatically and handle complex sensor observations.

However, learning from pixels is challenging: visual observations are high-dimensional, supervision is often limited or expensive to collect, and errors can compound over time as the agent visits states not covered by training data. These challenges are especially pronounced in real-world robotics and driving, where interaction data can be costly, slow, or safety-critical. As a result, recent work has emphasized data-efficient learning, including stronger IL/RL baselines, better augmentations, and pretraining strategies that improve downstream policy learning.

Problem Setup

We model visuomotor control as a sequential decision-making problem. Let the environment evolve over discrete time steps \(t = 1,2,\dots,T\). The agent receives an observation \(o_t \in \mathcal{O}\) (e.g., an RGB image or stacked frames), chooses an action \(a_t \in \mathcal{A}\) (e.g., steering/throttle or robot joint commands), and the environment transitions to the next state while emitting reward \(r_t\) (for RL) or providing supervision via expert actions (for IL).

Interaction and Trajectories

A (partial-observation) trajectory can be written as:

\(\) \tau = {(o_1, a_1, r_1), (o_2, a_2, r_2), \dots, (o_T, a_T, r_T)}. \(\)

A parametrized policy \(\pi_\theta(a_t \mid o_t)\) maps observations to either:

- Deterministic actions: \(a_t = \pi_\theta(o_t)\), or

- Stochastic actions: \(a_t \sim \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid o_t).\)

Objectives

Reinforcement Learning (RL). The goal is to maximize expected discounted return:

\(\) \max_\theta ; \mathbb{E}{\tau \sim \pi\theta}\left[\sum_{t=1}^{T} \gamma^{t-1} r_t\right], \(\)

where \(\gamma \in (0,1]\) is the discount factor.

Imitation Learning (IL). Given an offline dataset of expert demonstrations \(\mathcal{D} = {(o_i, a_i^{*})}_{i=1}^{N}\), behavior cloning typically minimizes a supervised loss:

\(\) \min_\theta ; \mathbb{E}{(o,a^) \sim \mathcal{D}}\left[\mathcal{L}\big(\pi\theta(o), a^\big)\right], \(\)

where \(\mathcal{L}\) is often MSE (continuous control) or cross-entropy (discrete actions).

Approaches

Broadly, modern visuomotor policy learning can be organized into three families: imitation learning, reinforcement learning, and pretraining-based methods that improve either of the above.

Imitation Learning

Imitation learning learns directly from expert behavior (e.g., human driving or teleoperated robot demonstrations). The simplest and most common approach is behavior cloning (BC), which treats policy learning as supervised learning from \(o \mapsto a^*\).

A key limitation is distribution shift: small errors can cause the policy to drift into states not represented in the dataset, leading to compounding mistakes. Methods such as dataset aggregation (e.g., iteratively collecting corrections) and stronger regularization/augmentation are often used to improve robustness, especially in driving-like settings where stable, human-aligned behavior is preferred.

Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning optimizes behavior through interaction, using reward feedback to explore and improve. RL can achieve superhuman performance in principle, but often suffers from:

- high sample complexity (many environment interactions),

- sensitivity to reward design,

- instability during training (especially from pixels).

In robotics, RL is widely used in simulation and increasingly combined with offline data, strong augmentations, and representation learning to reduce real-world interaction requirements.

Policy and Representation Pretraining

Because real-world interaction is expensive, many recent methods pretrain visual representations or policy components before downstream IL/RL. Pretraining can leverage:

- large-scale unlabeled videos/images,

- self-supervised objectives (e.g., contrastive learning),

- action-aware objectives when actions (or pseudo-actions) are available.

This project’s later section (“Policy Pretraining”) focuses on two representative perspectives:

- Action-conditioned contrastive pretraining that explicitly aligns representations with control-relevant semantics, and

- A critical re-evaluation showing that strong learning-from-scratch baselines (with proper augmentation and architecture choices) can match or exceed frozen pretraining in many settings—highlighting that when pretraining helps depends heavily on domain alignment and experimental controls.

Policy Pretraining

Learning visuomotor policies directly from interaction data is often expensive, particularly in real-world robotic and autonomous driving settings. As a result, many approaches seek to improve sample efficiency by pretraining visual representations or policy components prior to downstream imitation or reinforcement learning. However, existing methods differ substantially in both how pretraining is performed and whether it consistently benefits policy learning.

In this section, we examine two complementary perspectives on policy pretraining. The first presents an action-conditioned contrastive learning framework that explicitly aligns representation learning with control objectives [1]. The second revisits the effectiveness of visual pretraining by comparing it against strong learning-from-scratch baselines, providing a critical assessment of when and why pretraining improves visuomotor policy learning [2].

Action-Conditioned Contrastive Policy Pretraining

In Learning to Drive by Watching YouTube Videos: Action-Conditioned Contrastive Policy Pretraining [1], Zhang et al. introduce Action-Conditioned Contrastive Policy Pretraining (ACO), a contrastive representation learning framework designed specifically for visuomotor policy learning. The work builds on MoCo-style self-supervised learning, but argues that standard visual contrastive objectives are insufficient for control tasks because they primarily encode appearance-based features rather than action-relevant semantics. ACO modifies the contrastive objective to explicitly incorporate action information, enabling representations that are better aligned with downstream imitation and reinforcement learning.

Motivation

Traditional visual pretraining methods, such as ImageNet supervision or instance-level contrastive learning, aim to distinguish images based on visual content. However, in visuomotor control, the key requirement is not visual discrimination per se, but the ability to identify which aspects of an observation are predictive of the correct action. For example, road curvature and lane markings are critical for driving decisions, whereas lighting conditions or background buildings are largely irrelevant. The authors hypothesize that contrastive pretraining should group observations that require similar actions, even if they differ significantly in visual appearance.

Method Overview

ACO extends standard contrastive learning by combining two types of positive pairs:

- Instance Contrastive Pairs (ICP): as in MoCo, two augmented views of the same image form a positive pair, encouraging general visual discriminability.

- Action Contrastive Pairs (ACP): two different images are treated as a positive pair if their associated actions are sufficiently similar (e.g., steering angles within a predefined threshold), regardless of visual similarity.

By jointly optimizing ICP and ACP objectives, ACO encourages representations that preserve general visual structure while emphasizing action-consistent features. This dual-objective design allows the model to retain the benefits of instance discrimination while mitigating its tendency to overfit to appearance-level features.

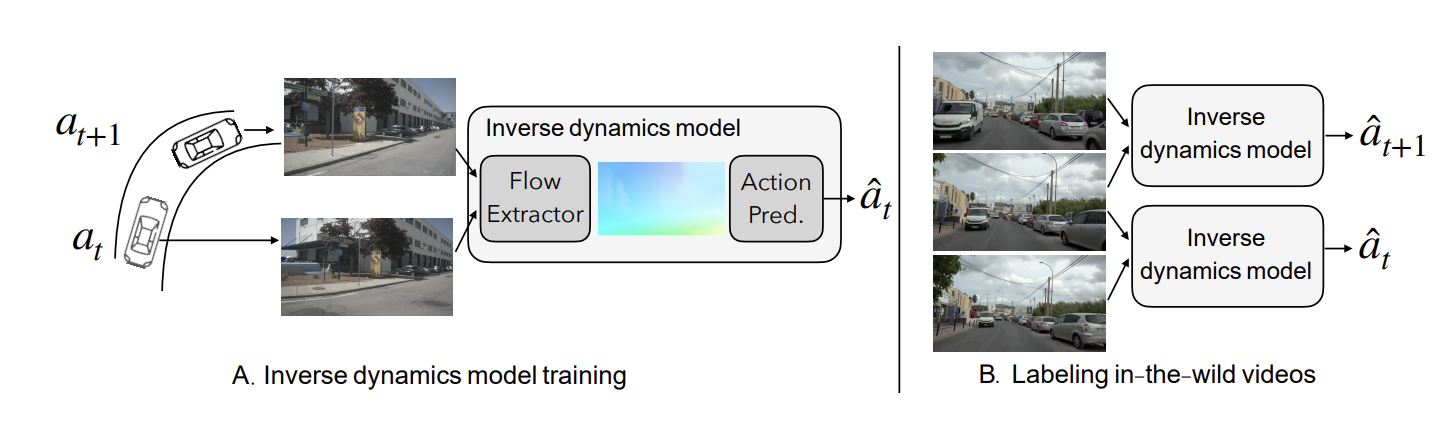

Pseudo Action Label Generation

A challenge in applying ACP at scale is the lack of action annotations in in-the-wild data such as YouTube videos. To address this, Zhang et al. train an inverse dynamics model on the NuScenes dataset, where ground-truth ego-motion actions are available. Given consecutive frames \((o_t, o_{t+1})\), the inverse dynamics model predicts the corresponding control action

\[\hat{a}*t = h(o_t, o*{t+1}),\]where \(h\) is trained using supervised regression. The trained inverse dynamics model is then applied to unlabeled YouTube driving videos to generate pseudo action labels, enabling large-scale action-conditioned pretraining without manual annotation. Importantly, optical flow is used as input to the inverse dynamics model instead of raw RGB frames, improving robustness to appearance variation and reducing prediction error.

Fig. 1. Inverse dynamics training on NuScenes and pseudo action label generation on YouTube driving videos [1].

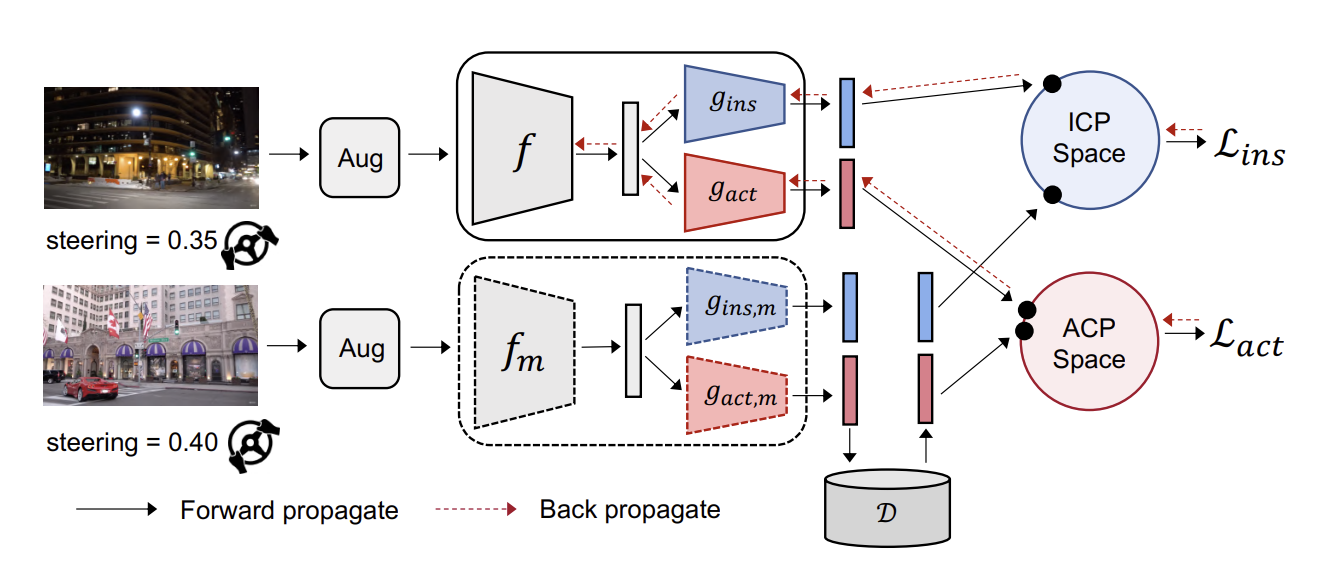

Training Architecture and Objective

The ACO architecture follows the MoCo framework and consists of a query encoder \(f\) and a momentum-updated key encoder \(f_m\). A shared visual backbone feeds into two projection heads: \(g_{\text{ins}}\) for the ICP objective and \(g_{\text{act}}\) for the ACP objective. Momentum-smoothed counterparts \(g_{\text{ins},m}\) and \(g_{\text{act},m}\) are used to populate a dictionary of negative samples.

The ICP loss follows the standard InfoNCE formulation:

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{ins}} = * \log \frac{\exp(z^q \cdot z^+ / \tau)} {\sum_{z \in \mathcal{N}(z^q)} \exp(z^q \cdot z / \tau)},\]where \(z^q\) is the query embedding, \(z^+\) is the positive key, \(\mathcal{N}(z^q)\) is the set of negatives, and \(\tau\) is a temperature parameter.

For ACP, the positive set is defined based on action similarity:

\[\mathcal{P}_{\text{act}}(z^q) = { z \mid \lVert \hat{a} - \hat{a}^q \rVert < \epsilon,\ (z,\hat{a}) \in \mathcal{K} },\]where \(\epsilon\) is a predefined action-distance threshold and \(\mathcal{K}\) denotes the key set. The ACP loss is then given by

\[\mathcal{L}_{\text{act}} = * \log \frac{\sum_{z^+ \in \mathcal{P}*{\text{act}}(z^q)} \exp(z^q \cdot z^+ / \tau)} {\sum*{z \in \mathcal{N}(z^q)} \exp(z^q \cdot z / \tau)}.\]The final training objective is a weighted combination of the two losses:

\[\mathcal{L} = \lambda_{\text{ins}} \mathcal{L}*{\text{ins}} + \lambda*{\text{act}} \mathcal{L}_{\text{act}}.\]

Fig. 2. ACO architecture showing joint optimization of instance contrastive and action-conditioned contrastive objectives [1].

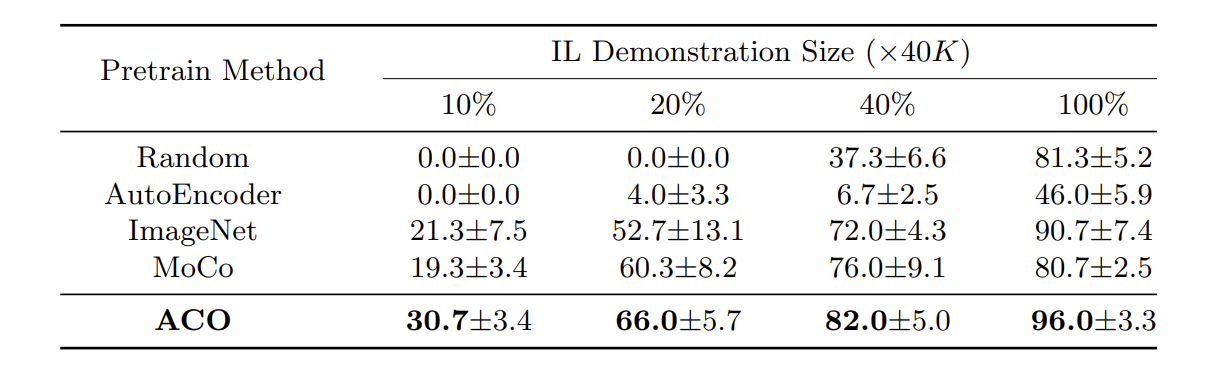

Experimental Results

The authors evaluate ACO on downstream imitation learning tasks in the CARLA driving simulator, comparing against random initialization, autoencoder pretraining, ImageNet pretraining, and MoCo. Across all demonstration sizes, ACO consistently outperforms the baselines, with the performance gap most pronounced in low-data regimes. These results indicate that action-conditioned pretraining substantially improves sample efficiency and leads to representations that are better aligned with downstream control objectives.

Fig. 3. Imitation learning performance under varying demonstration sizes for different pretraining methods [1].

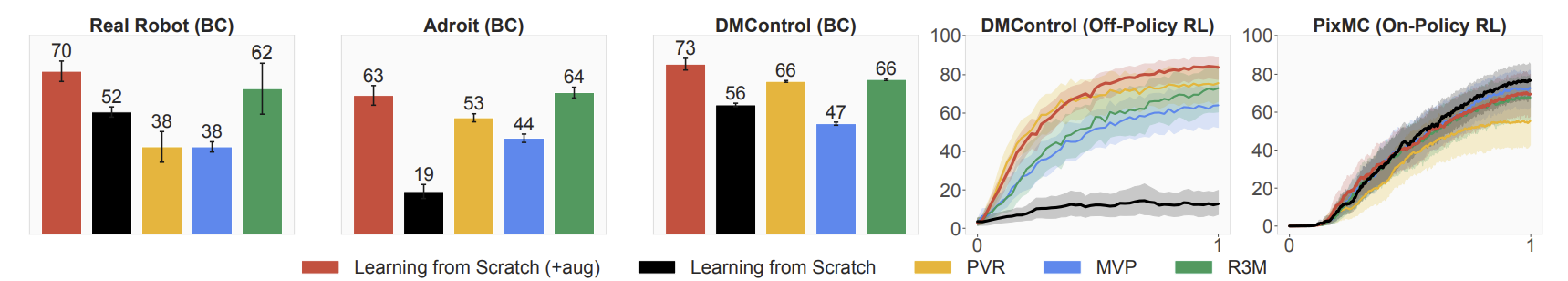

Pretraining Versus Learning-from-Scratch

In On Pre-Training for Visuo-Motor Control: Revisiting a Learning-from-Scratch Baseline [2], Hansen et al. provide a systematic re-evaluation of visual policy pretraining by comparing frozen pretrained representations against strong learning-from-scratch baselines. Rather than proposing a new pretraining method, this work examines whether commonly used pretrained visual encoders offer consistent advantages compared to baselines.

Problem Formulation

Learning-from-scratch refers to training a randomly initialized encoder \(f_\theta\) jointly with a policy head using only task-specific data:

\[\theta^* = \arg\min_\theta ; \mathbb{E}*{(o,a)\sim\mathcal{D}} \left[ \ell(\pi*\theta(o), a) \right],\]where \(\ell\) denotes a behavior cloning or reinforcement learning objective.

In contrast, frozen pretraining fixes a pretrained encoder \(f_{\text{pre}}\) and optimizes only the policy parameters:

\[\theta^* = \arg\min_\theta ; \mathbb{E}*{(o,a)\sim\mathcal{D}} \left[ \ell(\pi*\theta(f_{\text{pre}}(o)), a) \right].\]The authors emphasize that many prior works compare pretrained models against weak learning-from-scratch baselines that lack sufficient capacity or data augmentation.

Experimental Setup and Findings

Hansen et al. evaluate learning-from-scratch and frozen pretraining across multiple domains, including Adroit, DMControl, PixMC, and real-world robot manipulation, using behavior cloning, PPO, and DrQ-v2. The learning-from-scratch baselines employ shallow convolutional encoders paired with strong data augmentation, such as random shift and color jitter:

\[o' \sim \mathcal{T}(o),\]which substantially improves robustness and generalization.

Fig. 4. Comparison of learning-from-scratch and frozen pretrained representations across multiple domains [2].

Across most tasks and learning algorithms, learning-from-scratch with augmentation matches or exceeds the performance of frozen pretrained representations. Frozen pretraining provides only limited benefits in very low-data regimes, and no single pretrained representation consistently dominates across domains. The authors attribute this in part to a domain gap between pretraining data (real-world images and videos) and downstream environments (often simulated).

The authors further show that finetuning pretrained encoders on in-domain data,

\[\theta^* = \arg\min_\theta ; \mathbb{E}*{(o,a)\sim\mathcal{D}} \left[ \ell(\pi*\theta(f_\theta(o)), a) \right],\]can outperform both frozen pretraining and learning-from-scratch when combined with strong augmentation, highlighting the importance of domain adaptation.

Summary and Discussion

Taken together, the two works reviewed in this section offer complementary perspectives on policy pretraining for visuomotor control. Action-Conditioned Contrastive Policy Pretraining [1] demonstrates that pretraining can substantially improve downstream policy learning when the objective is explicitly aligned with action semantics, rather than relying solely on appearance-based visual similarity. By incorporating action-conditioned positives and leveraging large-scale unlabeled video data, ACO learns representations that are more directly relevant to control, yielding significant gains in low-data imitation and reinforcement learning settings.

In contrast, Hansen et al. [2] provide a critical re-evaluation of visual policy pretraining, showing that frozen pretrained representations do not consistently outperform strong learning-from-scratch baselines when data augmentation and architectural choices are properly controlled. Their findings highlight the importance of domain alignment and adaptation, suggesting that generic visual pretraining alone is insufficient to guarantee improvements in visuomotor policy learning.

Together, these results suggest that the effectiveness of policy pretraining depends not only on dataset scale, but more critically on the alignment between the pretraining objective and downstream control tasks. While action-aware and task-aligned pretraining objectives show clear promise, future work must carefully consider domain gaps, finetuning strategies, and strong baseline comparisons to fully realize the benefits of pretraining in visuomotor learning.

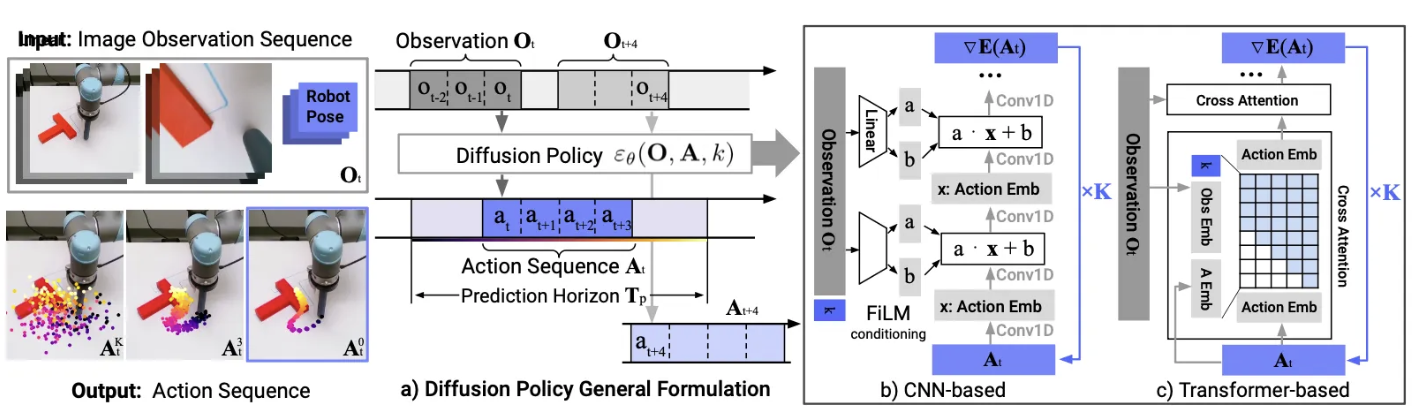

Diffusion Policy

Diffusion Policy is new paradigm introduced in 2023 by Chi et al [3]. It reframes visuomotor policy as a conditional diffusion process [3] over action sequences, conditioned on a short history of observations. By generating actions using iterative denoising, this new approach allows for more expressive multi-modal, high-dimensional manipulation, while improving temporal consistency in closed-loop control. In fact, the authors found that Diffusion Policy outperformed previous SoTA policies by 46.9% on average.

Problem formulation

Diffusion Policy is formulated as an offline visuomotor imitation learning problem. The goal is to learn a policy which maps camera observations to actions.

Diffusion Policy makes use of three distinct horizons: the observation horizon $T_o$, the prediction horizon $T_p$, and the action execution horizon $T_a$.

At some time $t$, Diffusion Policy doesn’t predict a single action $a_t$, but instead an action sequence $A_t$, conditioned on a recent observation history. More specifically, the model learns to predict

\[A_t=(a_t,a_{t+1}, ...,a_{t+T_p-1})\]given

\[O_t=(o_{t-T_o},o_{t-T_o+1},...,o_t)\]However, at inference time, only the first $T_a$ actions from $A_t$ are executed.

| More formally, Diffusion Policy trains a conditional denoising diffusion model to learn the conditional distribution $p(A_t | O_t)$, where $A_t$ is in action space. |

Prior research [3] has shown that standard supervised policies struggle with the multi-modal and temporally correlated action distributions introduced by manipulation demonstrations in imitation learning. Diffusion Policy improves on that, due to DDPM’s inherent capabilities with high-dimensional outputs [3], as well as predicting action sequences instead of individual actions.

Model architecture overview

Fig 5. Diffusion Policy Model Architecture [3].

At a high level, at each time step $t$, Diffusion Policy does the following:

- The visual encoder takes in the history of observations (images) $O_t$, and produces latent features $z_t$.

- The diffusion model diffuses the action sequence ${A_t}^{(k)}$, which at each denoising iteration $k$ is conditioned on $z_t$. It is worth noting that the same latents are reused for each diffusion time step $k$, because unlike some previous methods [3], Diffusion Policy is not predicting the joint distribution $p(A_t, O_t)$.

The controller then executes the first $T_a$ actions from $A_t$.

Let’s now do a deep dive into the two main components of Diffusion Policy.

Visual encoder deep dive

At each time step $t$, the visual encoder takes in the history of images $O_t$, and produces a sequence of embeddings $z_t$ which will be used as conditioning for the diffusion model.

The authors found that a slightly modified ResNet-18, without pre-training, performed the best for the visual encoder module. The model used differs from the regular ResNet-18 in the following ways:

- It uses spatial SoftMax pooling instead of global average pooling, to maintain spatial information [3].

- It replaces BatchNorm with GroupNorm, to stabilize training [3].

The outputs $z_t$ from the visual encoder are then fed into the diffusion model as conditioning.

Diffusion model deep dive

The diffusion model is the backbone of Diffusion Policy. At each diffusion time step $k$, the diffusion model takes in a noisy action sequence ${A_t}^{(k)}$, the diffusion time step $k$, and the conditioning features $z_t$ from the encoder. It then produces the predicted noise $\hat{\varepsilon}_{\theta}$, which is used to de-noise ${A_t}^{(k)}$ and obtain the next sample ${A_t}^{(k-1)}$.

The authors evaluated two backbone architectures for the diffusion model: CNN and time-series transformer.

CNN-based diffusion

The CNN-based diffusion uses a 1D temporal CNN as its backbone, adapted from previous work on using diffusion for sequence generation [3].

A method called FiLM is then used to condition the CNN on the conditioning latents $z_t$ [3]. FiLM generates a per-layer scale $\gamma(z_t)$ and shift $\beta(z_t)$, which are then applied to the layer’s activations. More specifically, at each layer, we apply the following transformation:

\[h \leftarrow \gamma(z_t) \circ h\]The authors recommend using this approach as a starting point, as well as for more basic tasks, as it is easy to set-up and requires little tuning. It does have performance limitations, however, as it struggles with fast-changing action.

Time-series diffusion transformer

The time-series diffusion transformer solves the issues with fast-changing action experienced by the CNN-based diffusion model.

In short, the noisy actions ${A_t}^{(k)}$ are passed in as input tokens to the transformer decoder blocks. The diffusion time step $k$ is also passed in as a token. The conditioning latents $z_t$ are embedded by an MLP, and passed in as conditioning features to the decoder. Each output token then corresponds to a component of $\hat{\varepsilon}_{\theta}$, which is used to de-noise ${A_t}^{(k)}$ into ${A_t}^{(k-1)}$.

The authors recommend using this approach if the CNN-based diffusion doesn’t lead to satisfactory results, or if the task at hand is more complex, as it is harder to set up and tune the transformer backbone.

Results & Limitations

Diffusion Policy significantly outperforms previous SoTA policies across a variety of tasks. On average, Diffusion Policy increased performance by 46.9%.

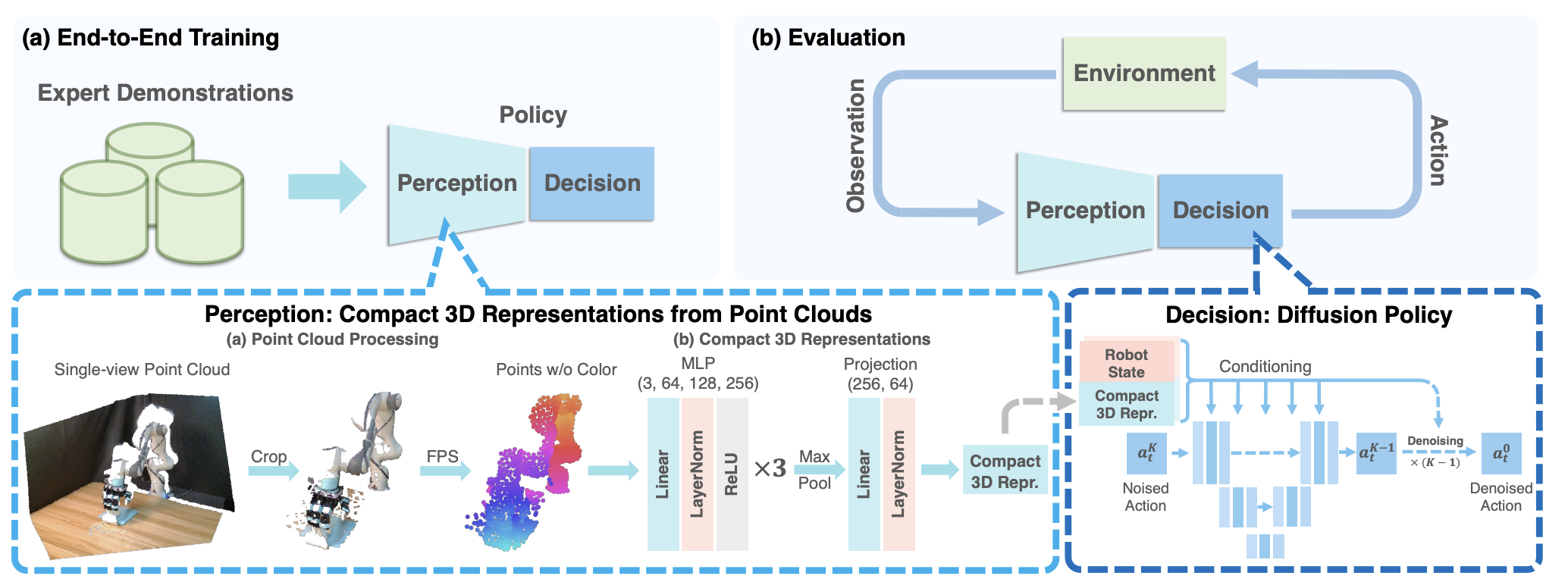

3D Diffusion Policy (DP3) [4]

Issues with Previous Work

The breakthrough work in Diffusion Policy [3] achieved near-human or human level performance on many tasks, proving that diffusion is a very promising direction. However, this model was incredibly data-hungry (approximately 100-200 demonstrations per task) and sensitive to camera viewpoint. Furthermore, these issues lead to the model committing safety violations, requiring interruption of the experiments by humans.

Solution

The authors of 3D Diffusion Policy: Generalizable Visuomotor Policy Learning via Simple 3D Representations hypothesized that with a 3D aware diffusion policy one could achieve much better results. Rather than using multi-view 2D images fed through a ResNet backbone to condition the action diffusion process, they cleverly converted the visual input from a single camera into a point cloud representation followed by an efficient point encoder. They found that with far fewer demonstrations (as few as 10), DP3 is able to handle tasks, surpass previous baselines, and commit far fewer safety violations.

The Perception Module [4]

First, 84 $\times$ 84 depth images from from the expert demonstrations are passed into the Perception Module. Using camera extrinsics and intrinsics, these are converted into point clouds. To improve generalization to different lighting and colors, they do not use color channels.

These point clouds often contain many redundant points, hence it can be very useful to downsample these. First, they crop all points not within a bounding box, eliminating useless points such as those on the ground or on the table. This is further downsampled to 1024 points using Farthest Point Sampling (FPS). FPS chooses an arbitrary start point, then iteratively chooses the furthest point from the set of those already selected and adds it, reducing the number of points while still being representative of the original image.

The final downsampled points are all fed into the DP3 Encoder. In the decoder, points are passed through a 3-layer MLP with LayerNorm, max-pooled, and finally projected into a compact vector, representing the entire 3D scene in a 64-dimensional vector. Surprisingly, this lightweight MLP encoder outperforms pre-trained models such as PointNet and Point Transformer (see the Ablation Studies sections).

The Decision Module [4]

The Decision Module is a conditional denoising diffusion model conditioned on robot poses and the 3D feature vector obtained from the Perception Module. Specifically, let $q$ be robot pose, $a^K$ be the final Gaussian noise, and $\epsilon_{\theta}$ be the denoising network. Then, the denoising network performs K iterations: \(a^{k-1}=\alpha_k(a^k - \gamma_k\epsilon_\theta(a^k, k, v, q)) + \sigma_k\mathcal{N}(0, 1)\)

until it reaches the noise-free action $a^0$. Here $\gamma_k$, $\alpha_k$, and $\sigma_k$ all come from the noise scheduler and are functions of k.

Training [4]

The training data consisted of a small set of expert demonstrations, usually 10-40 per task, collected via human tele-operation or scripted oracles. The model was trained on 72 simulation tasks across 7 domains as well as 4 real robot tasks - see results section for more details.

The training process samples a random $a^0$ from the data and conducts a diffusion process to get $\epsilon^k$ the noise at iteration k. Then, the objective is simply \(\mathcal{L} = MSE(\epsilon^k, \epsilon_\theta(\bar{\alpha}_k a^0 + \bar{\beta}_k\epsilon^k, k, v, q))\) where $\beta_k$ and $\bar{\alpha}_k$ are, again, functions of k from the noise scheduler. They use the same diffusion policy network architecture as the original 2D Diffusion Policy authors.

Fig 6. Overview of 3D Diffusion Policy. In the training phase, DP3 simultaneously trains its perception module and decision-making process end-to-end with expert demonstrations. During evaluation, DP3 determines actions based on visual observations from the environment. [4].

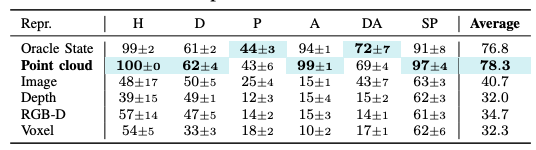

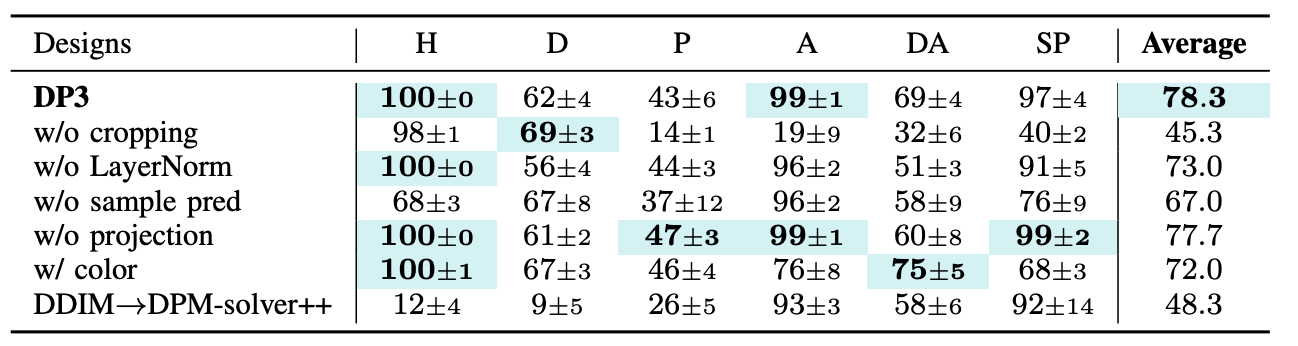

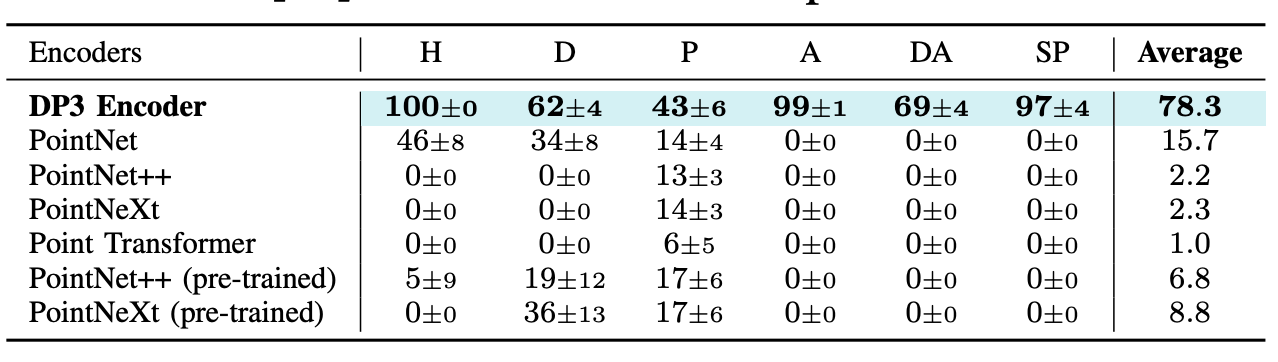

Ablation Studies [4]

The authors also performed several ablation studies to assess their design choices. They selected 6 tasks with 10 demonstrations each and ran ablations on different 3D representations, point cloud encoders, and other design choices. Here are some of their results:

Fig 7. Ablation on the choice of 3D representations. Point clouds perform the best. [4].

*Fig 8. Ablation on some design choices. * [4].

Surprisingly, the lightweight MLP Encoder greatly outperformed even pre-trained models such as PointNet and Point Transformer. Through careful analysis, the authors made modifications to PointNet and achieved competitive accuracy (72.3%) with their MLP decoder. Here are the original ablation results below:

*Fig 9. Ablation on choice of point cloud encoder. Surprisingly, the lightweight MLP encoder outperforms larger pre-trained models. * [4].

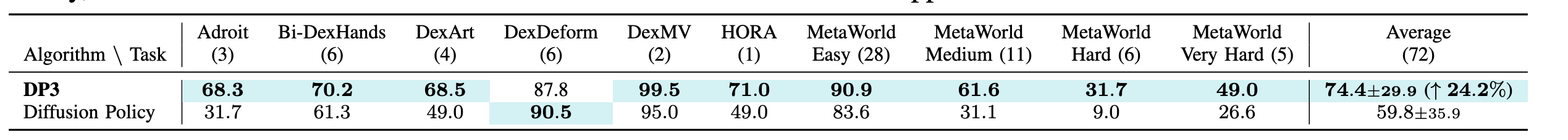

Results [4]

DP3 was benchmarked on a wide range of tasks spanning rigid, articulated, and deformable object manipulation. It achieved over 24% relative improvement compared to Diffusion Policy, converged much faster, and required far fewer demonstrations. Here are the main results on benchmarks for DP3 and other models:

*Fig 10. Main simulation results. Averaged over 72 tasks, DP3 achieves 24.2% relative improvement compared to Diffusion Policy, with a smaller variance. * [4].

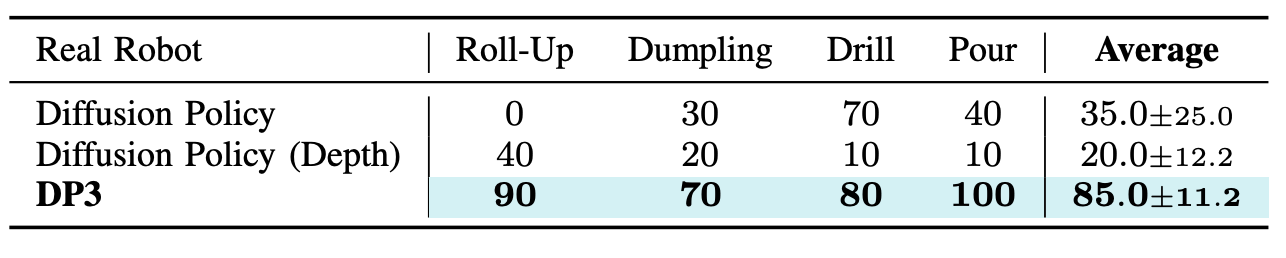

DP3 also excelled in real robot tasks with greater generality. In particular, the real robot tasks were:

- Roll-up: The Allegro hand wraps the plasticine multiple times to make a roll-up.

- Dumpling: The Allegro hand first wraps the plasticine and then pinchs it to make dumpling pleats.

- Drill: The Allegro hand grasps the drill up and moves towards the green cube to touch the cube with the drill.

- Pour: The gripper grasps the bowl, moves towards the plasticine, pours out the dried meat floss in the bowl, and places the bowl on the table.

For the sake of time, there were 40 demonstrations per task. See the table below for results on real-robot tasks:

*Fig 11. Results on real robot experiments with 10 tasks per trial. * [4].

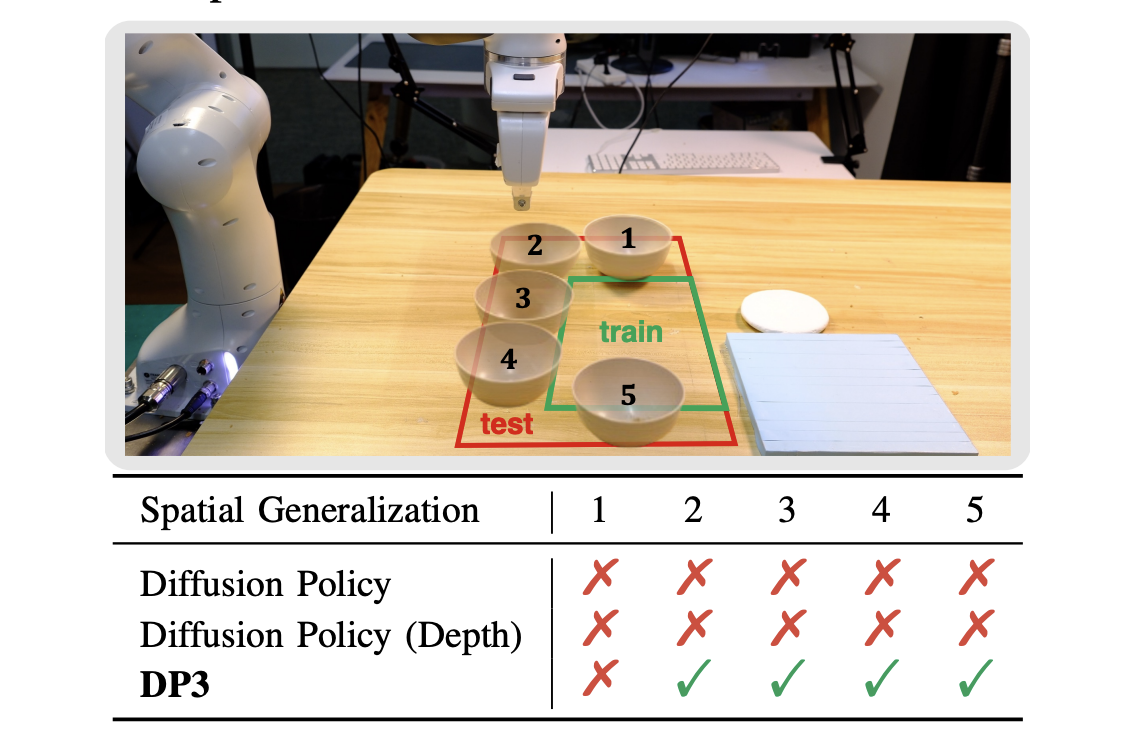

To further assess generalization capabilities, they studied spatial generalization with the Pour task, instance generalization on drill, and more. Here are some of their exciting results:

*Fig 12. Spatial Generalization on Pour: The authors placed the bowl at 5 different positions that are unseen in the training data. Each position was evaluated with only one trial. * [4].

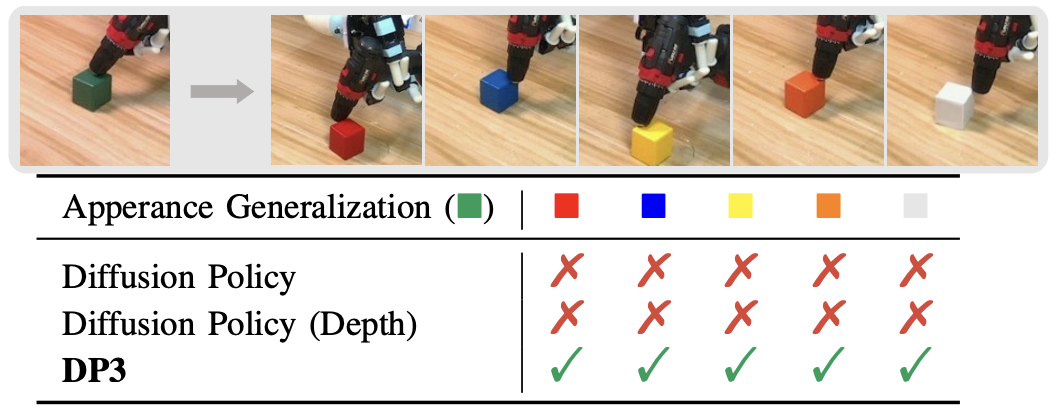

*Fig 13. Color/Appearance Generalization on Drill: The authors placed the bowl at 5 different positions that are unseen in the training data. Each position was evaluated with only one trial. * [4].

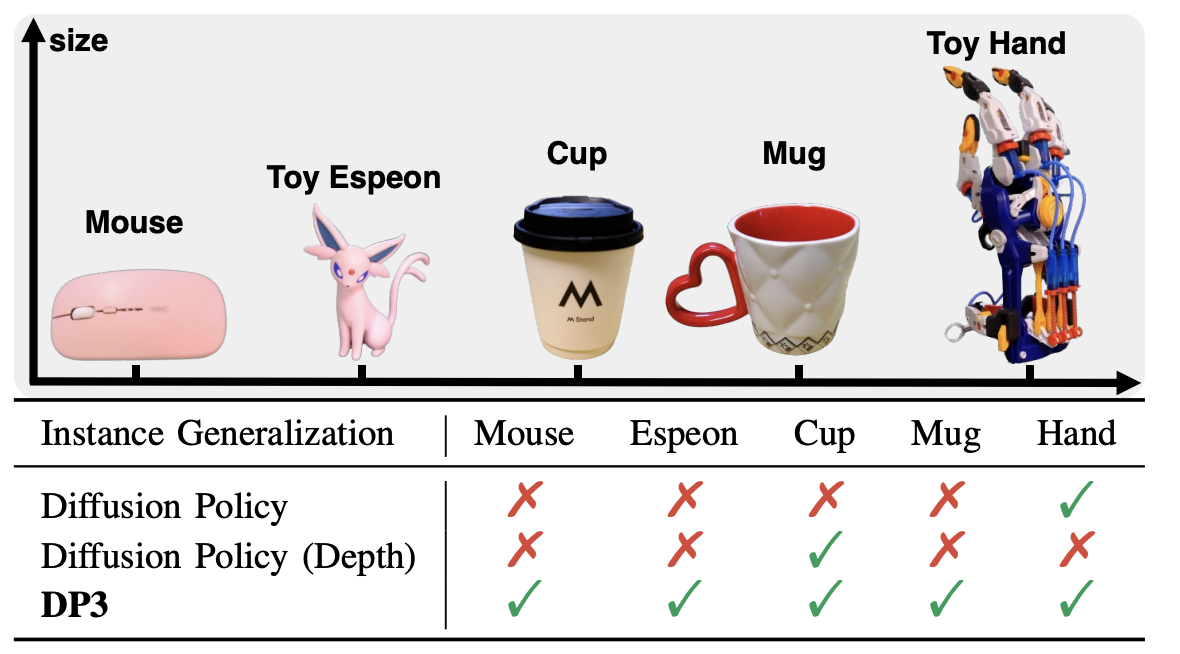

*Fig 14. Instance generalization on Drill. The authors replaced the cube used in Drill with five objects in varied sizes from our daily life. Each instance is evaluated with one trial. * [4].

This generalizability of the model is perhaps the most crucial aspect, as robots will have to handle many different conditions in real-world applications. The instance generalization is an especially promising result, as it suggests possibilities for 0-shot learning on very similar tasks to training data.

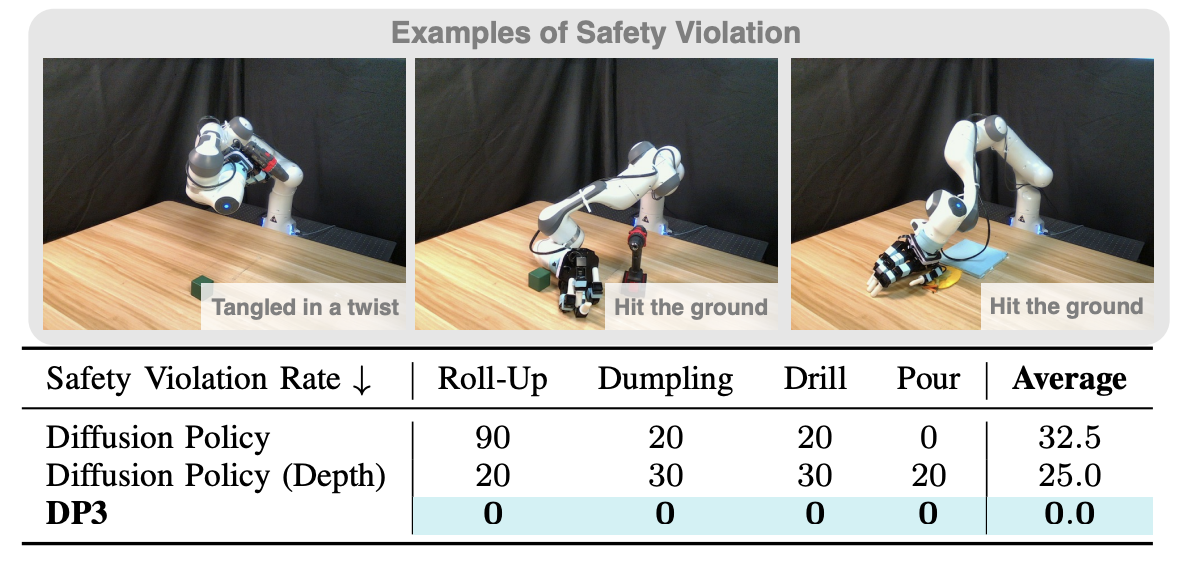

Finally, the authors also present encouraging results about safety. They define a safety violation as “unpredictable behaviors in real-world experiments, which necessitates human termination to ensure robot safety.” Below are the safety results for DP3 and Diffusion Policy:

*Fig 15. Average safety violation rates. DP3 rarely committed any safety violations, in contrast to the other models. * [4].

They found that DP3 rarely makes safety violations, and suspect this is due to its 3D awareness, though further work needs to be carried out in this direction.

Discussion and Impact of DP3 [4]

Overall, DP3 represents a major step forward from 2D Diffusion Policy by showing that a simple, well-designed 3D representation—sparse point clouds plus a lightweight MLP encoder—is enough to dramatically improve data efficiency, generalization, and safety in visuomotor diffusion policies. However, despite their success, the authors believe that the optimal 3D representation is yet to be discovered. Furthermore, these tasks had relatively short horizons, and they acknowledge that much work needs to be done for tasks with extremely long horizons. Despite these limitations, DP3 has already lead to future work and been built upon in many other projects. For example, ManiCM [5] improves on inference speed, one of the most pressing practical issues. By distilling the multi-step denoising process into a consistency model that can generate actions in single step, ManiCM preserves the strengths of DP3’s 3D-aware policy while making it more suitable for real-time control. Taken together, DP3 and its extensions like ManiCM suggest that 3D diffusion policies are not just a one-off improvement over 2D image-based methods, but a robust foundation for future work in Imitation Learning for visuo-motor policy.

References

[1] Zhang, Qihang, et al. “Learning to Drive by Watching YouTube Videos: Action-Conditioned Contrastive Policy Pretraining.” European Conference on Computer Vision, 2022.

[2] Hansen, Nicklas, et al. “On Pre-Training for Visuo-Motor Control: Revisiting a Learning-from-Scratch Baseline.” International Conference on Learning Representations, 2023.

[3] Chi, Cheng, Zhenjia Xu, Shuran Song, and others.

“Diffusion Policy: Visuomotor Policy Learning via Action Diffusion.”

arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04137, 2023.

[4] Ze, Yanjie, Yiming Zhang, Zhiyang Dou, Xingyu Lin, and Shuran Song.

“3D Diffusion Policy: Generalizable Visuomotor Policy Learning via Simple 3D Representations.”

arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03954, 2024.

[5] Lu, Guanxing, Zifeng Gao, Tianxing Chen, Wenxun Dai, Ziwei Wang, Wenbo Ding, and Yansong Tang. “ManiCM: Real-time 3D Diffusion Policy via Consistency Model for Robotic Manipulation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.01586, 2024.