From Labeling to Prompting: The Paradigm Shift in Image Segmentation

The evolution from Mask R-CNN to SAM represents a paradigm shift in computer vision segmentation, moving from supervised specialists constrained by fixed vocabularies to promptable generalists that operate class-agnostically. We examine the technical innovations that distinguish these approaches, including SAM’s decoupling of spatial localization from semantic classification and its ambiguity-aware prediction mechanism, alongside future directions in image segmentation.

Introduction

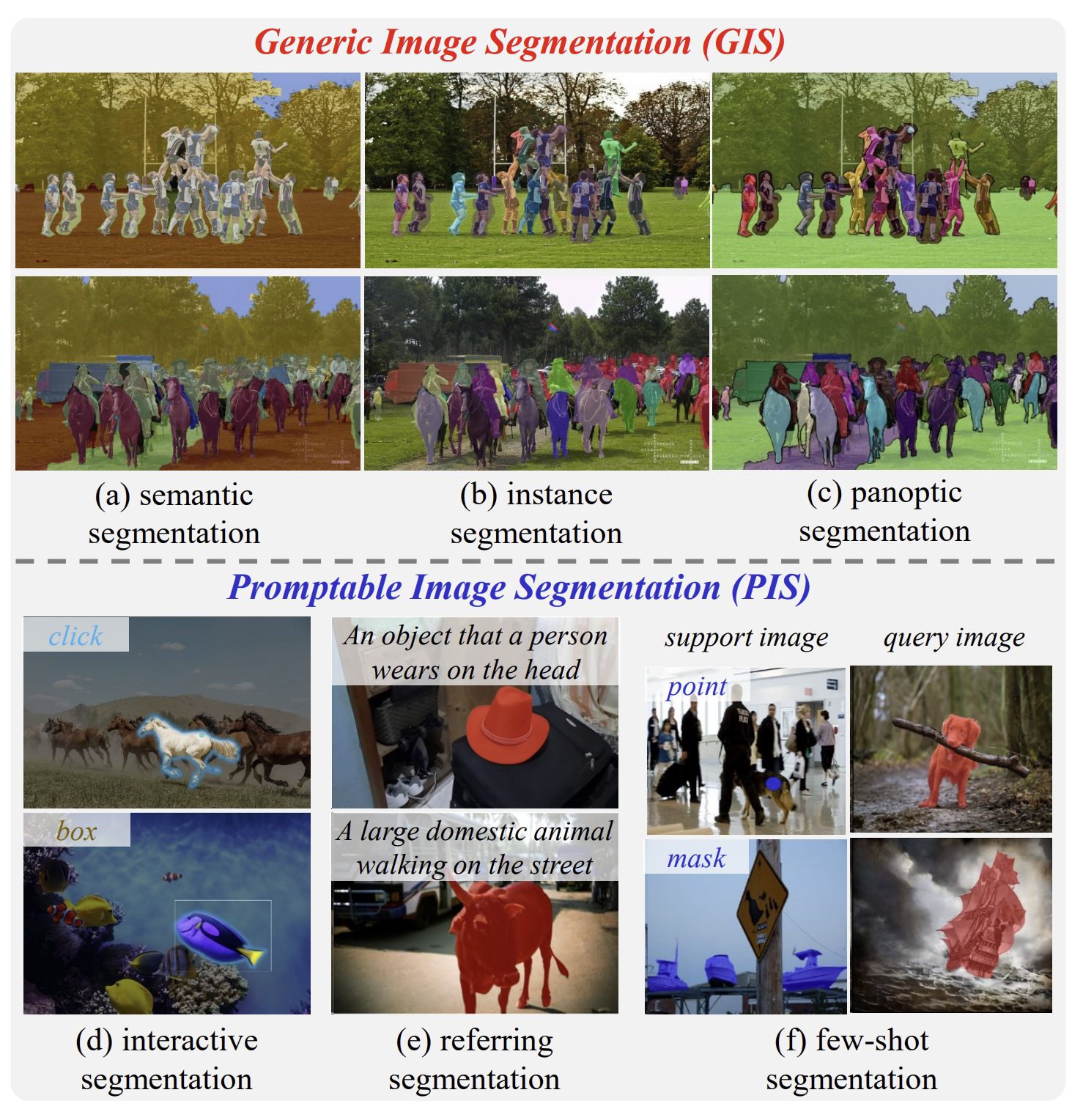

For the past decade, the “holy grail” of computer vision was fully automated perception: teaching a machine to look at an image and assign a semantic label to every pixel. The 2024 survey “Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey” by Zhou et al defines this era as “Generic Image Segmentation” (GIS), which was dominated by supervised specialists. One of the pinnacles of this approach was Mask R-CNN, a framework that efficiently detected objects and generated high-quality masks in parallel. While powerful, these models were fundamentally limited by their training data. They were “closed-vocabulary” systems that could only see what they were explicitly taught to label.

To formalize this limitation, the 2024 survey introduces a unified formulation for the segmentation task: \(f: \mathcal{X} \mapsto \mathcal{Y} \quad \text{where} \quad \mathcal{X} = \mathcal{I} \times \mathcal{P}\) Here, I represents the image and P represents the user prompt. In the specialist era of Mask R-CNN, the prompt set was empty, forcing the model to rely entirely on learned semantics to determine the output. [1]

Figure 1 from “Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey”.

Figure 1 from “Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey”.

We are now witnessing a “new epoch” in computer vision driven by the rise of Foundation Models. The paradigm is shifting from passive labeling to active prompting. Leading this is the Segment Anything Model (SAM), which introduced the “promptable segmentation task”. Unlike its predecessors, SAM acts as a “segmentation generalist” that may not know what an object is but knows exactly where it is given a simple click or box prompt.

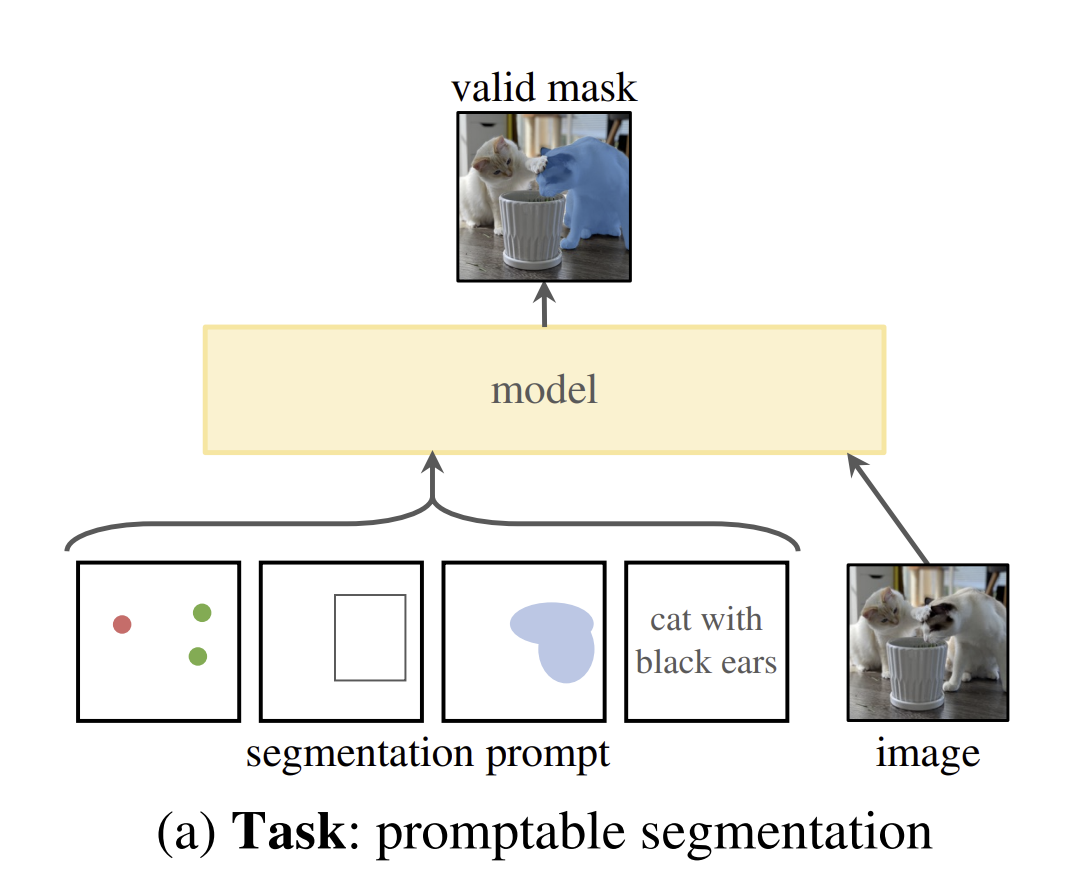

Figure 1 from “Segment Anything”.

Figure 1 from “Segment Anything”.

Our discussion of the two models explores this transition by contrasting the supervised precision of Mask R-CNN with the zero-shot flexibility of SAM, discussing how the move from curated datasets to massive “data engines” is redefining what it means for a machine to “see”.

Mask R-CNN

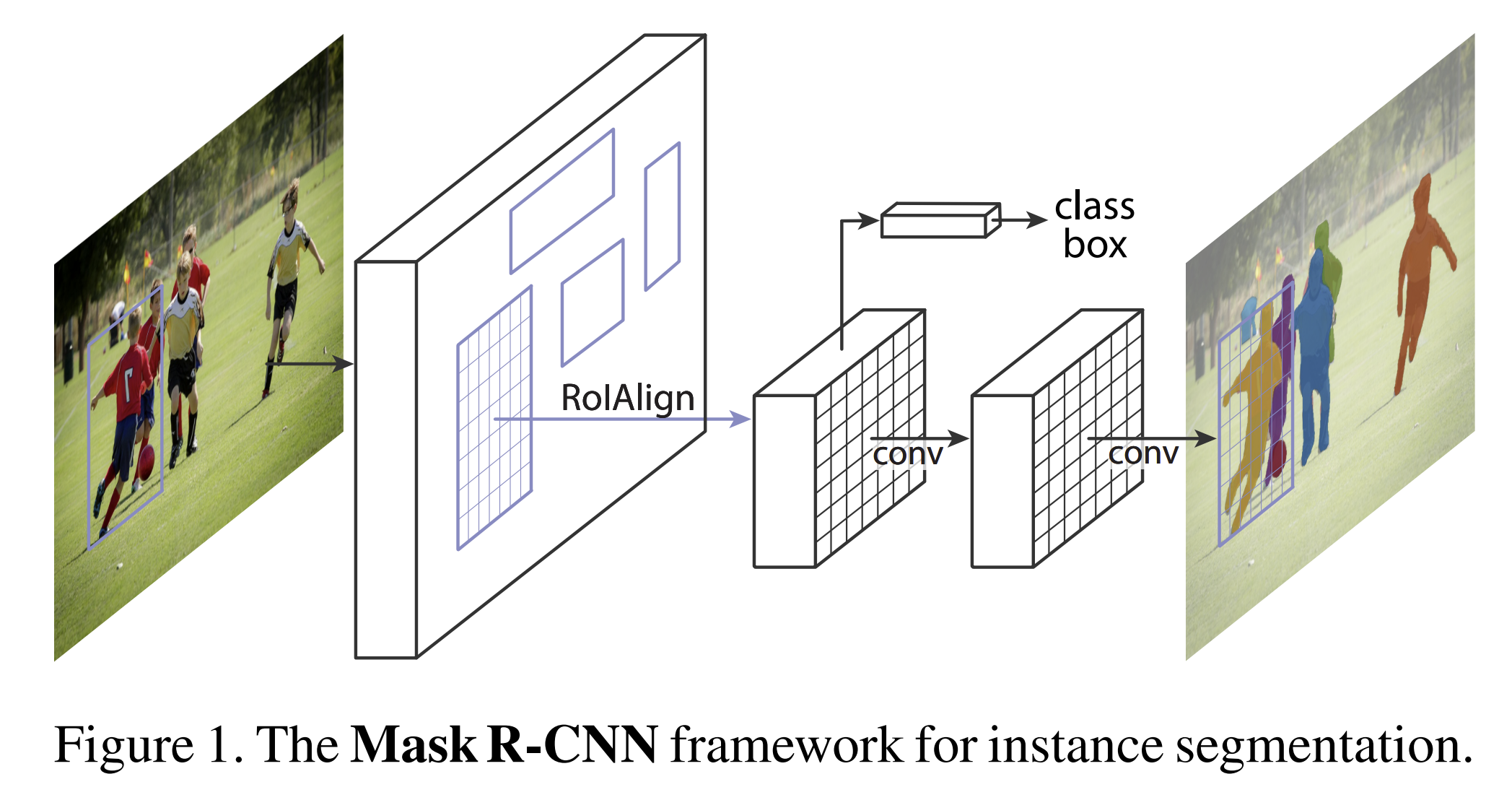

Mask R-CNN represents one of the culmination of the supervised segmentation era, exemplifying both the strengths and limitations of closed-vocabulary, instance-level segmentation systems. Designed to assign fixed semantic labels, such as “person” or “car” to every pixel belonging to an object instance, it operates with precision on known categories. Unlike segmentation-first approaches that group pixels before classification, Mask R-CNN adopts an instance-first strategy by detecting object bounding boxes first, then segmenting the pixels within those regions. This design allows segmentation to run parallel to detection, providing a clean conceptual separation between the two tasks. However, achieving pixel-accurate masks required precise spatial alignment, something earlier detection pipelines struggled to provide.[3]

Figure 1 from “Mask R-CNN”.

Figure 1 from “Mask R-CNN”.

Architecture:

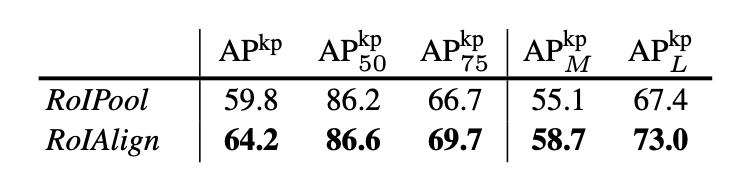

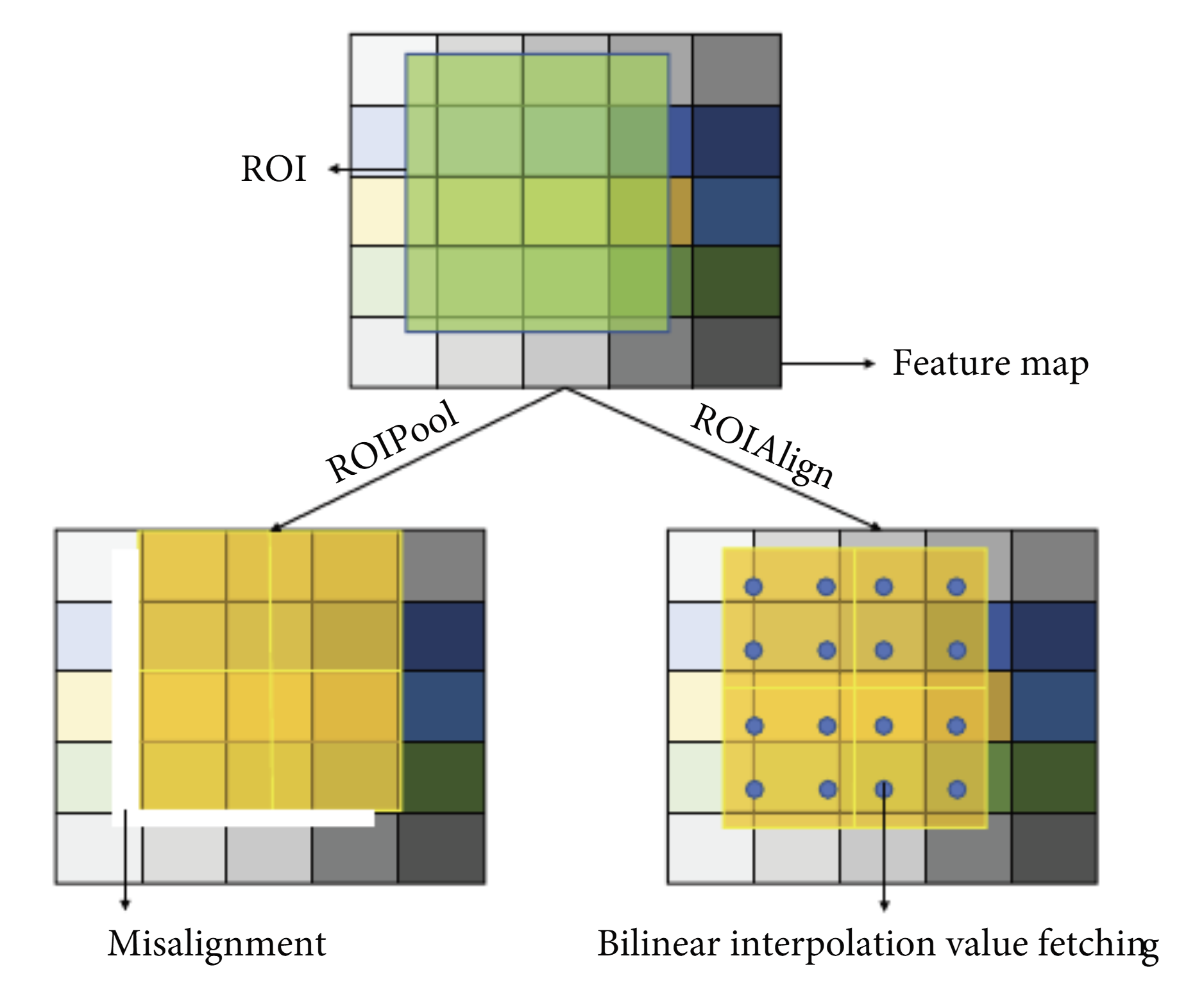

The breakthrough that elevated Mask R-CNN to exception was an innovation known as RoIAlign which solved a critical spatial alignment problem. Prior methods relied on RoIPool which used coarse quantization when mapping regions of interest to feature maps. This introduced misalignments which were okay when it came to bounding box detection but catastrophic for pixel-level segmentation accuracy. RoIAlign came and eliminated quantization, using bilinear interpolation to preserve spatial coordinates. This led to dramatic improvements in mask accuracy, going from 10% to 50% across benchmarks, showing how spatial precision was the primary bottleneck in achieving quality segmentation. [3]

Table 6. RoIAlign vs. RoIPool for keypoint detection on minival. The backbone is ResNet-50-FPN.

Figure 3, “Research on Intelligent Detection and Segmentation of RockJoints Based on Deep Learning”.

Figure 3, “Research on Intelligent Detection and Segmentation of RockJoints Based on Deep Learning”.

Mask R-CNN’s efficiency stems from its decoupling of mask prediction from class prediction. The architecture predicts binary masks independently for every class without inter-class competition. The classification branch determines object identity while the mask branch focuses exclusively on spatial extent within detected regions. This separation of concerns enabled Mask R-CNN to surpass all competing single-models entries on the COCO object detection challenges, establishing it as the dominant approach for instance segmentation tasks. The mask loss, is the average binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss over all pixels in the RoI, calculated only for the ground-truth class:

\[L_{\text{mask}} = \frac{1}{M^2} \sum_{i=1}^{M^2} \text{BCE}\bigl(p_i^{k}, y_i^{k}\bigr)\]Despite its advances in computer vision, Mask R-CNN operates within a crucial limitation because it functions as a closed-vocabulary model, capable of segmenting only those object categories encountered during training. Extending the model to recognize new categories requires substantial data collection, labor-intensive pixel-level annotation, and complete model retraining. This rigidity, inherent to the supervised learning paradigm, ultimately necessitated the evolution toward promptable architectures like SAM, which transcend fixed category constraints through foundation model approaches.

Segment Anything (SAM)

In the GIS era, models like Mask R-CNN were designed as “all-in-one” systems. They were trained to simultaneously localize an object and assign it a specific semantic label from a fixed vocabulary (e.g., class_id: 1 for “person”). The architecture explicitly coupled these tasks: the network’s classification branch and mask branch ran in parallel, meaning the model could only segment what it could also recognize. The Segment Anything Model (SAM) flips this paradigm. [1]

Created by Meta AI, SAM fundamentally redefines the segmentation task so that instead of predicting a fixed class label for every pixel, the goal is to return a valid segmentation mask for any prompt. It is trained to be class-agnostic. It does not output a semantic label; instead, it outputs a “valid mask” and a confidence score reflecting the object’s “thingness” rather than its category. SAM essentially understands structure (boundaries, occlusion, and connectivity) without necessarily understanding semantics. It knows that a pixel belongs to a distinct entity, but it relies on the prompter to define the context. This shift transforms the model from a static labeler into an interactive “generalist” that decouples the concept of “where an object is” (segmentation) from “what an object is” (semantics).

GIF of SAM UI, taken from: https://learnopencv.com/segment-anything/.

GIF of SAM UI, taken from: https://learnopencv.com/segment-anything/.

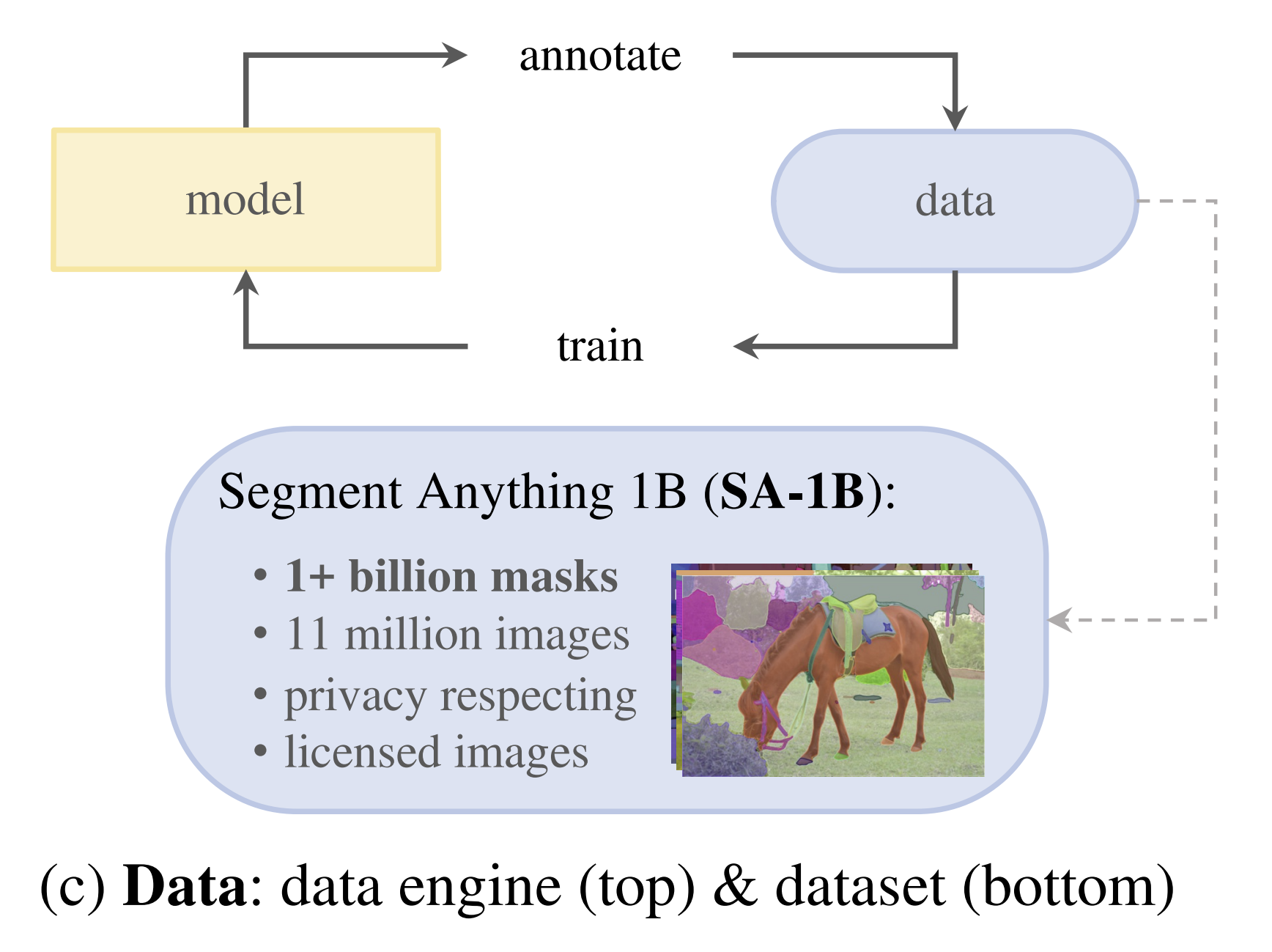

In the supervised era, models like Mask R-CNN were limited by the high cost of manual pixel-level annotation. To overcome this, SAM utilized a “Data Engine” as follows:

- Assisted-Manual: Annotators used a SAM-powered tool to label masks, working 6.5x faster than standard COCO annotation.

- Semi-Automatic: The model automatically labeled confident objects (like “stuff” categories), allowing annotators to focus on difficult, less prominent objects.

- Fully Automatic: The model lastly ran on 11 million images to generate the SA-1B dataset, containing 1.1 billion masks (400x larger than any existing segmentation dataset).

Figure 1 from “Segment Anything”.

Figure 1 from “Segment Anything”.

This massive scale allowed SAM to learn a generalized notion of “thingness” that transfers zero-shot to underwater scenes, microscopy, and ego-centric views without specific retraining. [2]

Architecture:

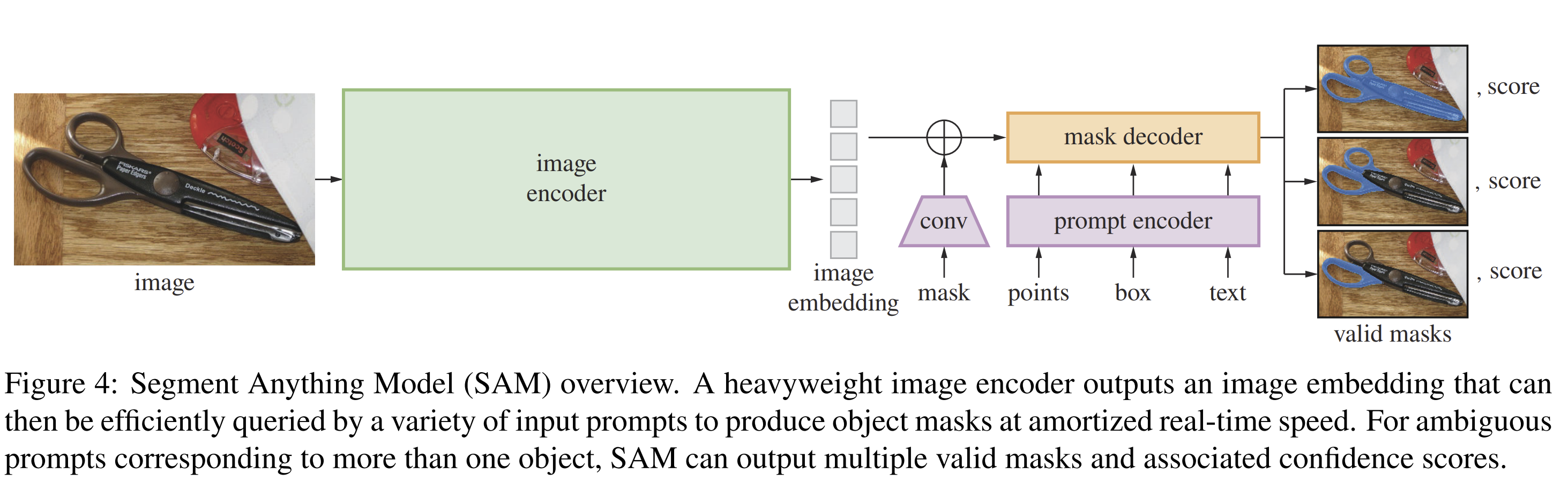

SAM achieves real-time interactivity through a distinct three-part architecture that separates heavy computation from fluid interaction.

Figure 4 from “Segment Anything”.

Figure 4 from “Segment Anything”.

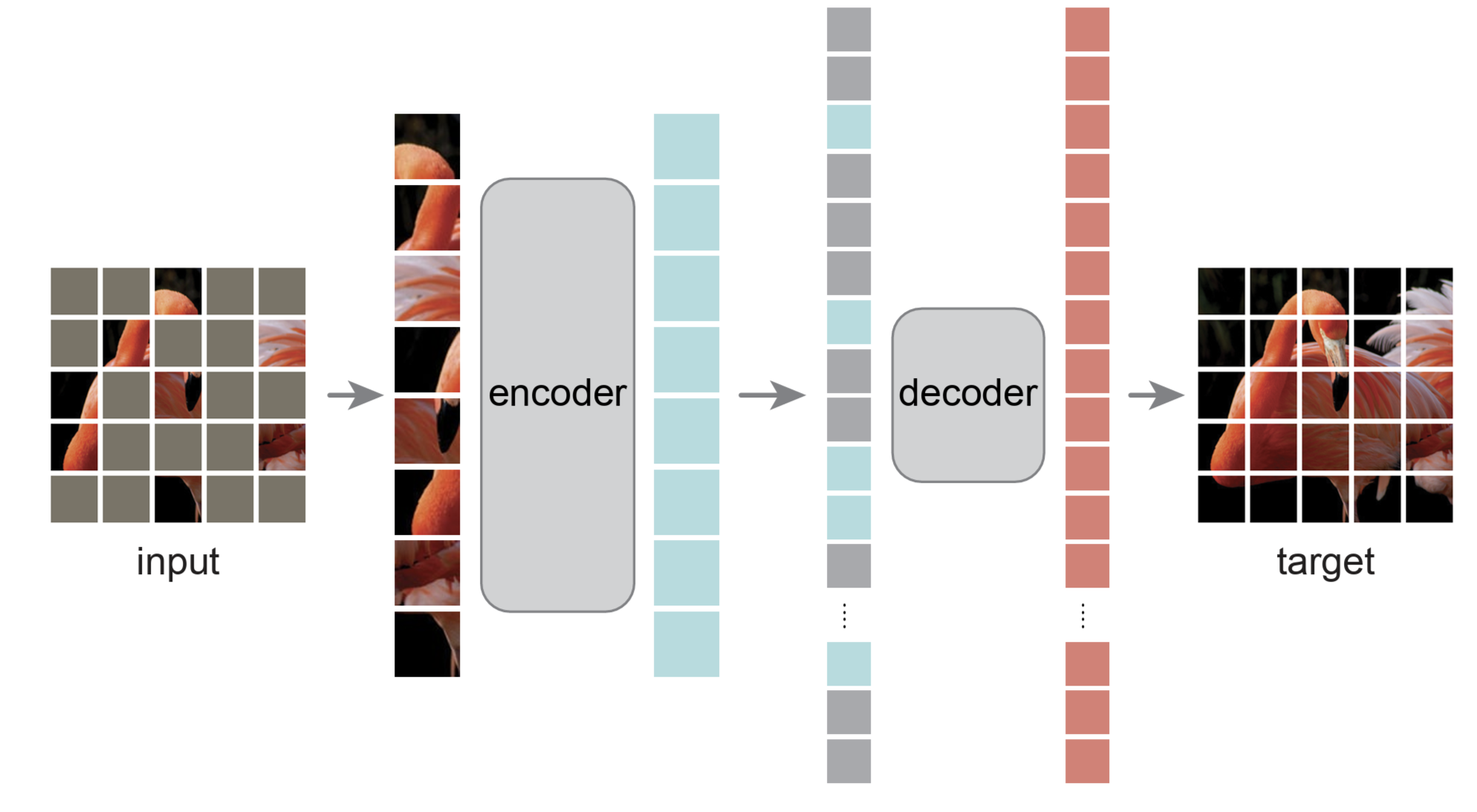

The backbone of SAM is a Vision Transformer (ViT) pre-trained using Masked Autoencoders (MAE). Unlike standard supervised pre-training, MAE masks a large portion of the input image patches (e.g., 75%) and forces the model to reconstruct the missing pixels.This self-supervised approach allows the model to learn robust, scalable visual representations without human labels. In SAM, this encoder runs once per image, outputting a 64 x 64 image embedding. While computationally expensive, this cost is “amortized” over the interaction because once the embedding is calculated, the model can respond to hundreds of prompts in milliseconds.

Figures 1 and 3 from “Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners”.

Figures 1 and 3 from “Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners”.

The image encoder produces a high-dimensional embedding that preserves spatial structure. Unlike traditional CNNs that progressively downsample, the ViT maintains a 64 x 64 grid where each location encodes rich contextual information about that region. This design is essential for allowing the downstream decoder to perform pixel-precise localization even though the encoder operates at 16x downsampled resolution.

To enable the “promptable” paradigm, SAM represents sparse inputs (points, boxes, text) as positional encodings:

- Points & Boxes: Represented by positional encodings summed with learned embeddings for each prompt type.

- Text: Processed via an off-the-shelf CLIP text encoder, bridging the gap between language and pixels.

Dense prompts (masks) are handled differently by being embedded using convolutions and summed element-wise with the image embedding. This enables SAM to accept a previous mask prediction as input, allowing iterative refinement, a key capability for interactive use cases where users progressively correct the model’s output.

The decoder is a modification of a Transformer decoder block that efficiently maps the image embedding and prompt embeddings to an output mask. It utilizes a mechanism of cross-attention to update the image embedding with prompt information:

\[\text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left( \frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}} \right) V\]In this context, the prompt tokens act as queries (Q) to attend to the image embedding (K, V), ensuring the model focuses only on the regions relevant to the user’s input.

The decoder performs bidirectional cross-attention where not only do prompt tokens query the image embedding, but the image embedding also queries the prompt tokens. This two-way information flow allows the model to both focus on relevant regions (prompt-to-image) and update its understanding based on spatial context (image-to-prompt). After two decoder blocks, the model upsamples the updated image embedding and applies a dynamic linear classifier (implemented as an MLP) to predict per-pixel mask probabilities.

A critical innovation in SAM is its ambiguity awareness. In the Mask R-CNN era, a single input had to correspond to a single ground truth. However, a point on a person’s shirt is ambiguous: does the user want the shirt or the person?

To solve this, SAM predicts three valid masks for a single prompt (corresponding to the whole, part, and sub-part) along with confidence scores (IoU), allowing the user or downstream system to resolve the ambiguity. This design choice acknowledges that segmentation is inherently ill-posed (i.e., a single input can have multiple valid outputs), a nuance often ignored by previous fully supervised specialists.

SAM is trained with a multi-task loss combining focal loss and dice loss in a 20:1 ratio. The focal loss addresses class imbalance by down-weighting easy examples, while the dice loss directly optimizes for mask overlap (IoU). Critically, when SAM predicts multiple masks, only the mask with the lowest loss receives gradient updates (a technique that prevents the model from averaging over ambiguous ground truths). SAM also predicts an IoU score for each mask, trained via mean-squared-error loss, which enables automatic ranking of predictions without human intervention. The total loss is formulated as:

\(L_{\text{total}} = \bigl(20 \cdot L_{\text{focal}} + L_{\text{dice}}\bigr) + L_{\text{MSE}}\) \(\underbrace{20 \cdot L_{\text{focal}} + L_{\text{dice}}}_{\text{Mask Prediction}} \quad + \quad \underbrace{L_{\text{MSE}}}_{\text{IoU Ranking}}\)

During training, SAM also simulates interactive annotation by sampling prompts in 11 rounds per mask, including one initial prompt (point or box), 8 iteratively sampled points from error regions, and 2 refinement iterations with no new points. This forces the model to learn both initial prediction and self-correction, making it robust to imperfect prompts in deployment. [2]

Results:

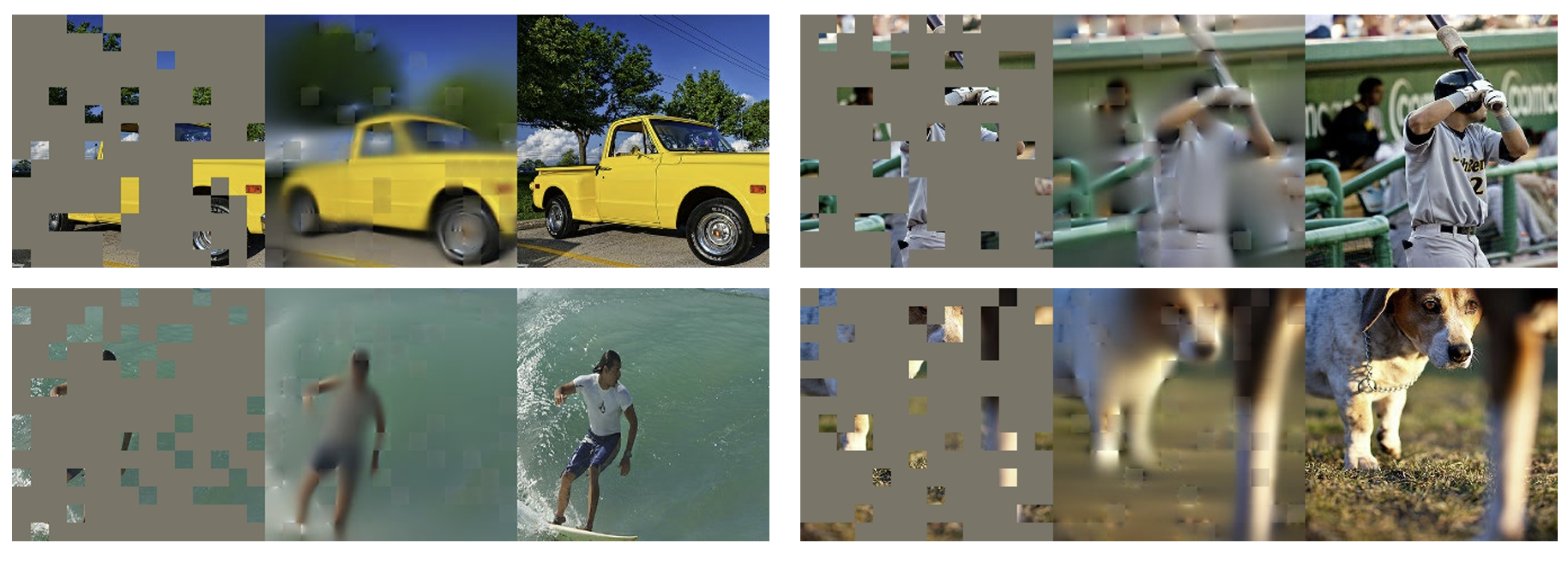

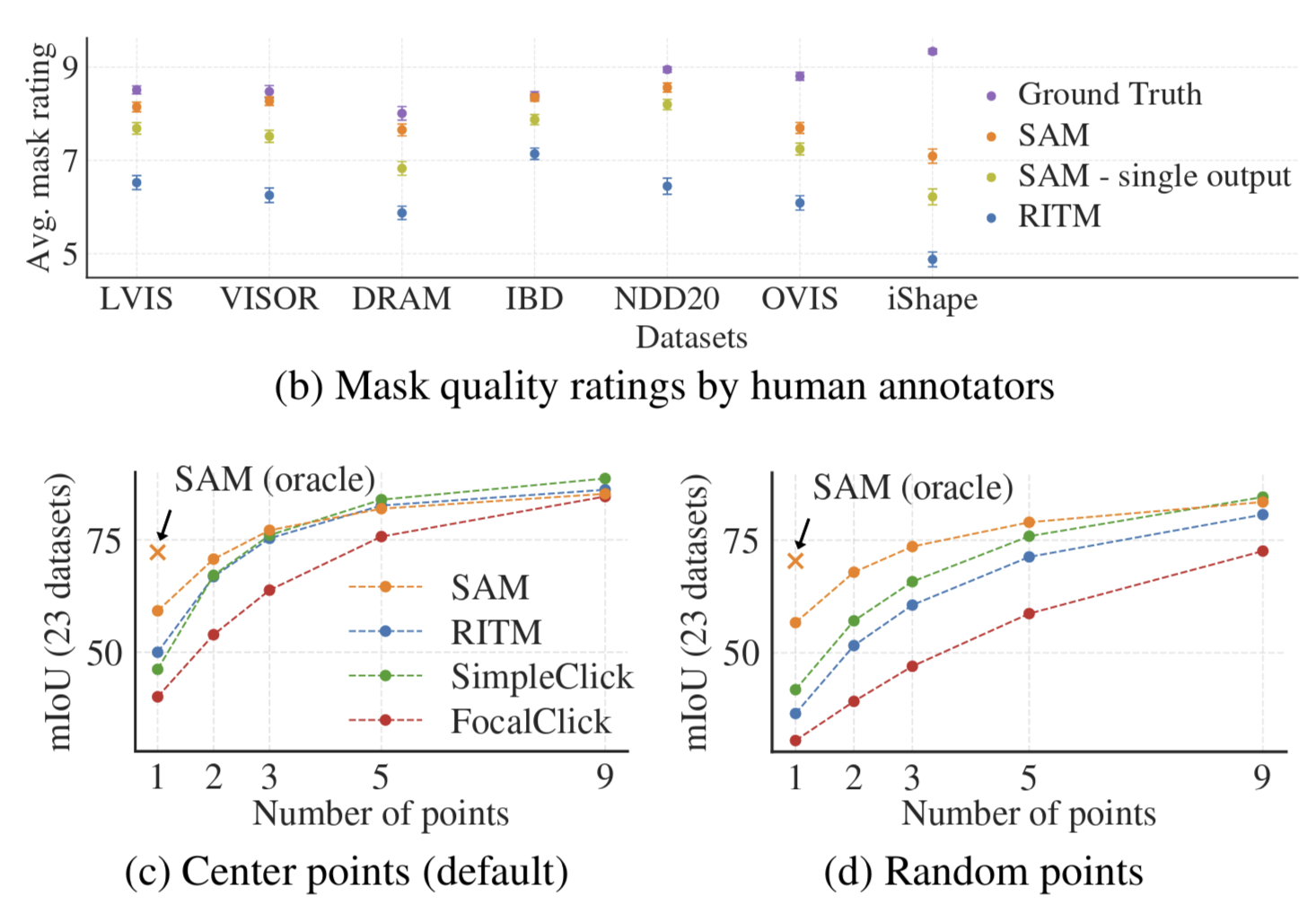

Figures 9 from “Segment Anything”.

Figures 9 from “Segment Anything”.

Upon its release, SAM demonstrated unprecedented zero-shot generalization across 23 diverse segmentation datasets spanning underwater imagery, microscopy, X-ray scans, and ego-centric video. On single-point prompts, SAM achieved competitive IoU with specialist models like RITM, but critically, human annotators rated SAM’s masks 1-2 points higher (on a 1-10 scale) than the strongest baselines of the time. This gap revealed a key limitation of IoU metrics because SAM produced perceptually better masks that effectively segmented valid objects, even when they differed from the specific ground truth, resulting in artificially deflated scores. [2]

Discussion

Training Paradigms

Mask R-CNN relies entirely on manually curated datasets like COCO and Cityscapes, which require pixel-level annotation. The model’s understanding was fundamentally bottlenecked by human time and effort. SAM flipped this paradigm by making the segmentation model itself the primary data generator. Instead of humans doing the work, the model proposes masks while humans simply validate and correct mistakes. This created a virtuous cycle that produced 1.1 billion masks, a scale utterly impossible with manual annotation alone. In the foundation model era, how data is collected may be as important as the model architecture itself.

The Semantic Gap

The most important conceptual difference between Mask R-CNN and SAM lies in how they handle semantics. Mask R-CNN tightly couples segmentation and classification, where every predicted mask corresponds to a predefined category. This makes the model effective within its training distribution but also enforces a closed vocabulary.

SAM deliberately breaks this coupling. It focuses on identifying coherent regions in an image without assigning semantic labels. In doing so, segmentation becomes a modular capability rather than a final output. SAM can be combined with other components (object detectors, language models, or task-specific logic) that provide semantic interpretation separately. This separation allows segmentation to function as general visual infrastructure that can support many downstream tasks without retraining.

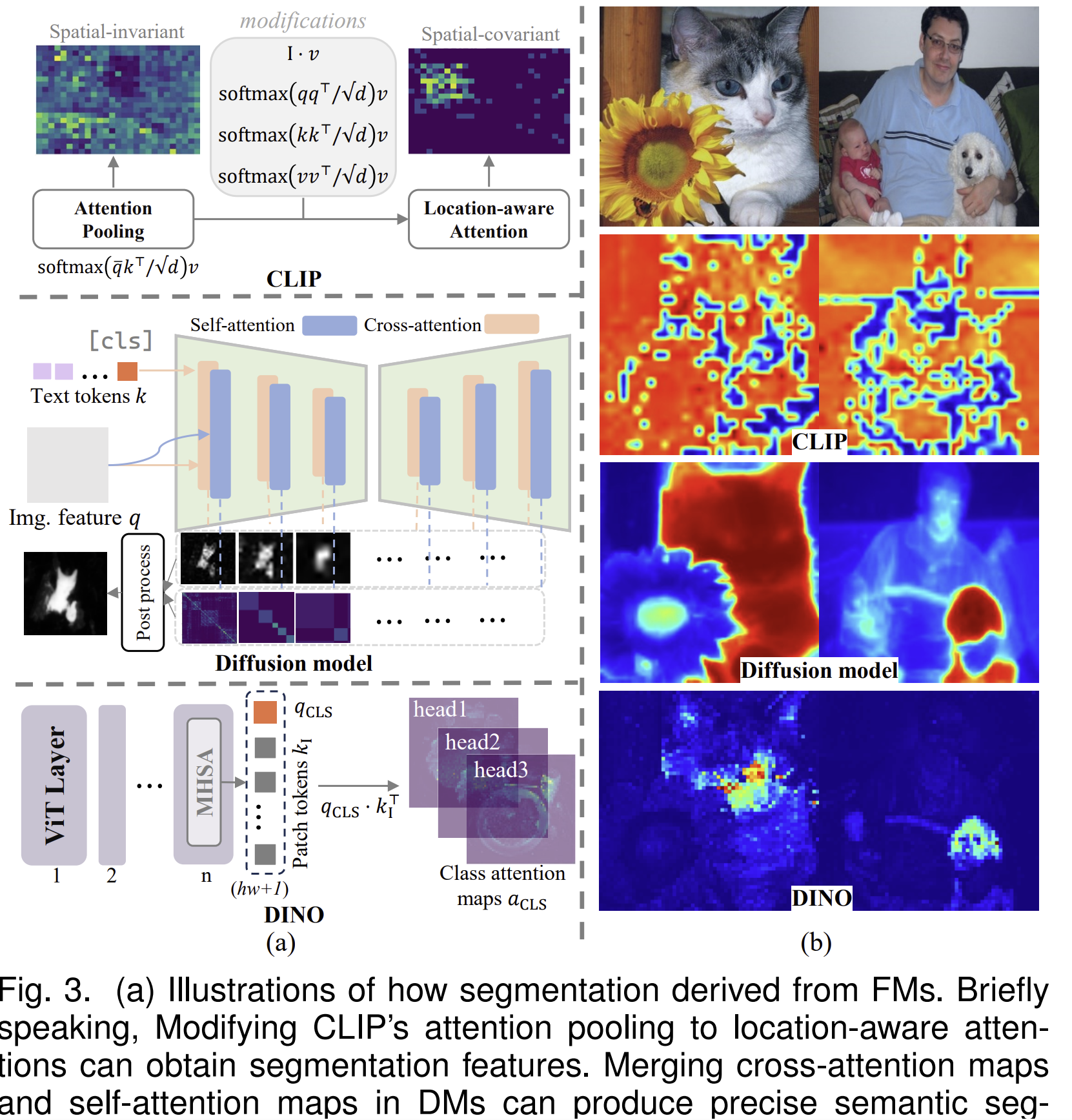

The Future: Towards Unified Perception

SAM represents a significant milestone, but recent developments suggest the field is moving beyond promptable segmentation. Models like DINO and Stable Diffusion now perform segmentation as an emergent capability, despite never being explicitly trained for it. Optimized for self-supervised learning and image generation respectively, these models spontaneously learn to group pixels into coherent objects. This suggests that segmentation may arise naturally from learning good visual representations, rather than requiring dedicated training.

Figure 3 from “Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey”.

Figure 3 from “Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey”.

These observations point toward unified perception systems that blur traditional task boundaries. Instead of separate modules for detection, segmentation, and classification, future architectures may provide continuous visual understanding from which any capability can be extracted as needed. The integration of large language models with vision systems exemplifies this trend, enabling reasoning about images at multiple levels simultaneously (e.g. like from pixel groupings to semantic relationships to natural language descriptions).

The current landscape is characterized by coexisting paradigms rather than outright replacement. Specialist models remain optimal for well-defined domains with stable data distributions and strict performance requirements. Foundation models provide flexible infrastructure for open-world scenarios where generalization matters most. Emergent capabilities in self-supervised systems hint at a future where task boundaries dissolve entirely. Effective computer vision practice now requires combining these complementary approaches correctly for the right tasks.

References

[1] Zhou, T., Xia, W., Zhang, F., Chang, B., Wang, W., Yuan, Y., Konukoglu, E., & Cremers, D. (2024). Image Segmentation in Foundation Model Era: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.12957. <https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.12957>

[2] Kirillov, A., Mintun, E., Ravi, N., Mao, H., Rolland, C., Gustafson, L., Xiao, T., Whitehead, S., Berg, A. C., Lo, W.-Y., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2023). Segment Anything. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 4015-4026. <https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.02643>

[3] He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2017). Mask R-CNN. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2961-2969. <https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06870>

[4] Peng, L., Wang, H., Zhou, C., Hu, F., Tian, X., & Hongtai, Z. (2024). Research on Intelligent Detection and Segmentation of Rock Joints Based on Deep Learning. Complexity, 2024, Article ID 8810092. <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1155/2024/8810092>

[5] He, K., Chen, X., Xie, S., Li, Y., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. (2022). Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 16000-16009. <https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.06377>