Global Human Mesh Recovery

In this blog post, we introduce and discuss recent advancements in global human mesh recovery, a challenging computer vision problem involving the extraction of human meshes on a global coordinate system from videos where the motion of the camera is unknown.

Introduction

Human mesh recovery (HMR) is the task of reconstructing a complete and accurate 3D mesh model of the human body and its pose from a single RGB image, with impressive results achieved especially in controlled settings.

However, a problem with significantly less research progress is global human mesh recovery, in which a model takes in a monocular video with unknown camera motion and outputs a coherent sequence of human meshes in a world grounded coordinate system. This introduces significant challenges, including disentangling camera movement from human movement, enforcing temporal consistency, and ensuring physical plausibility to eliminate artifacts like foot sliding. Producing a global human mesh recovery model that works underneath these constraints would unlock applications spanning augmented and virtual reality, film production, sports analysis, human-computer interaction and more.

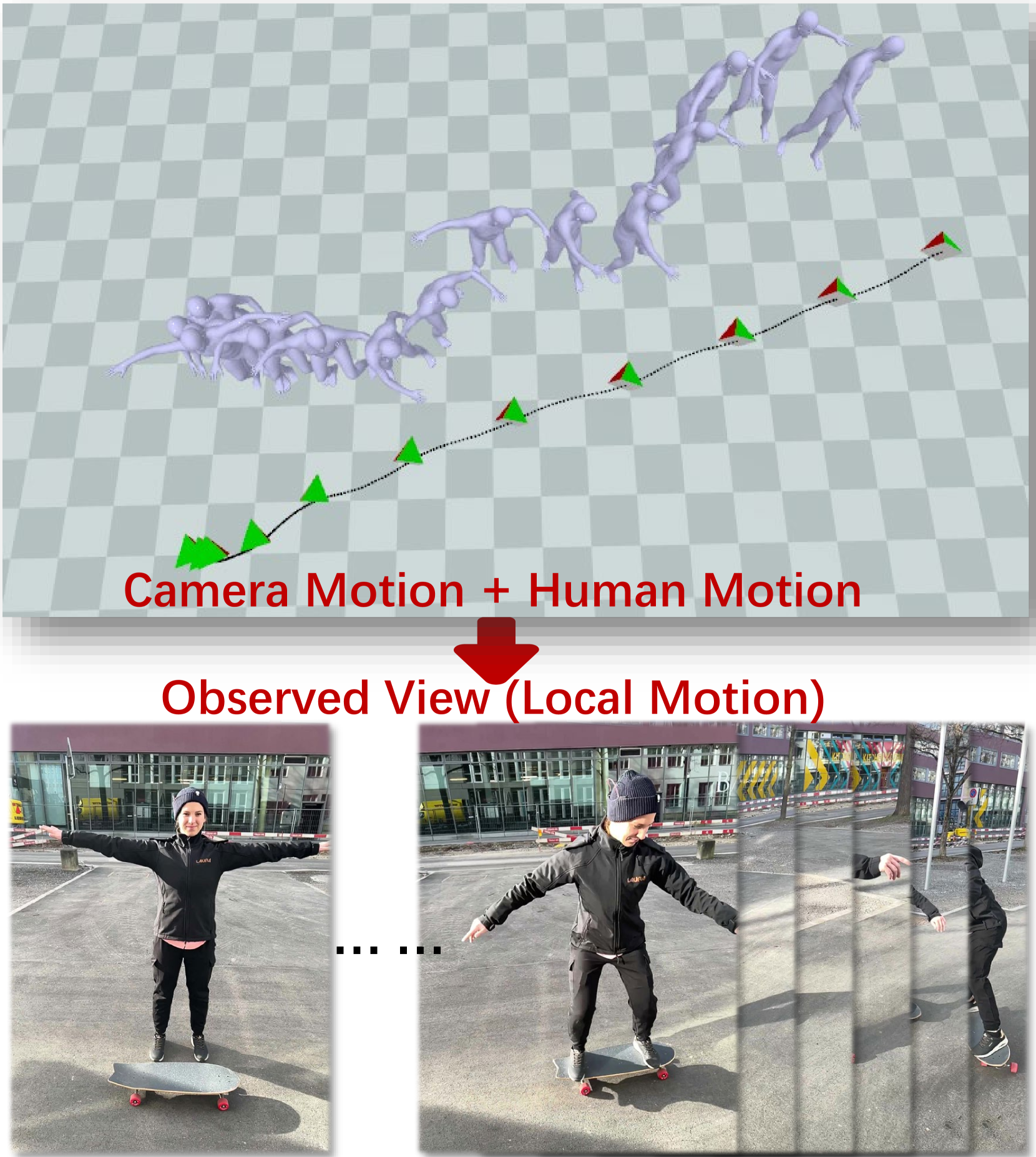

Fig 1. Deriving a trajectory from the global frame requires accounting for camera movement in addition to the observed local motion 1

To address these challenges, researchers have pursued complementary approaches that build upon each other. We will analyze the progression from foundational methods, SLAHMR and TRACE (CVPR 2023), which focused on decoupling camera motion and ensuring temporal smoothness, respectively. These techniques laid the groundwork for the WHAM model (CVPR 2024), which achieves superior world-grounded accuracy and physical plausibility through contact-aware trajectory recovery.

Background/Foundation

Modern human mesh recovery methods rely primarily on parametric body models that represent the human body as a set of learnable parameters rather than estimating thousands of vertex positions, which would be necessary in the case of directly recovering a 3D triangle mesh.

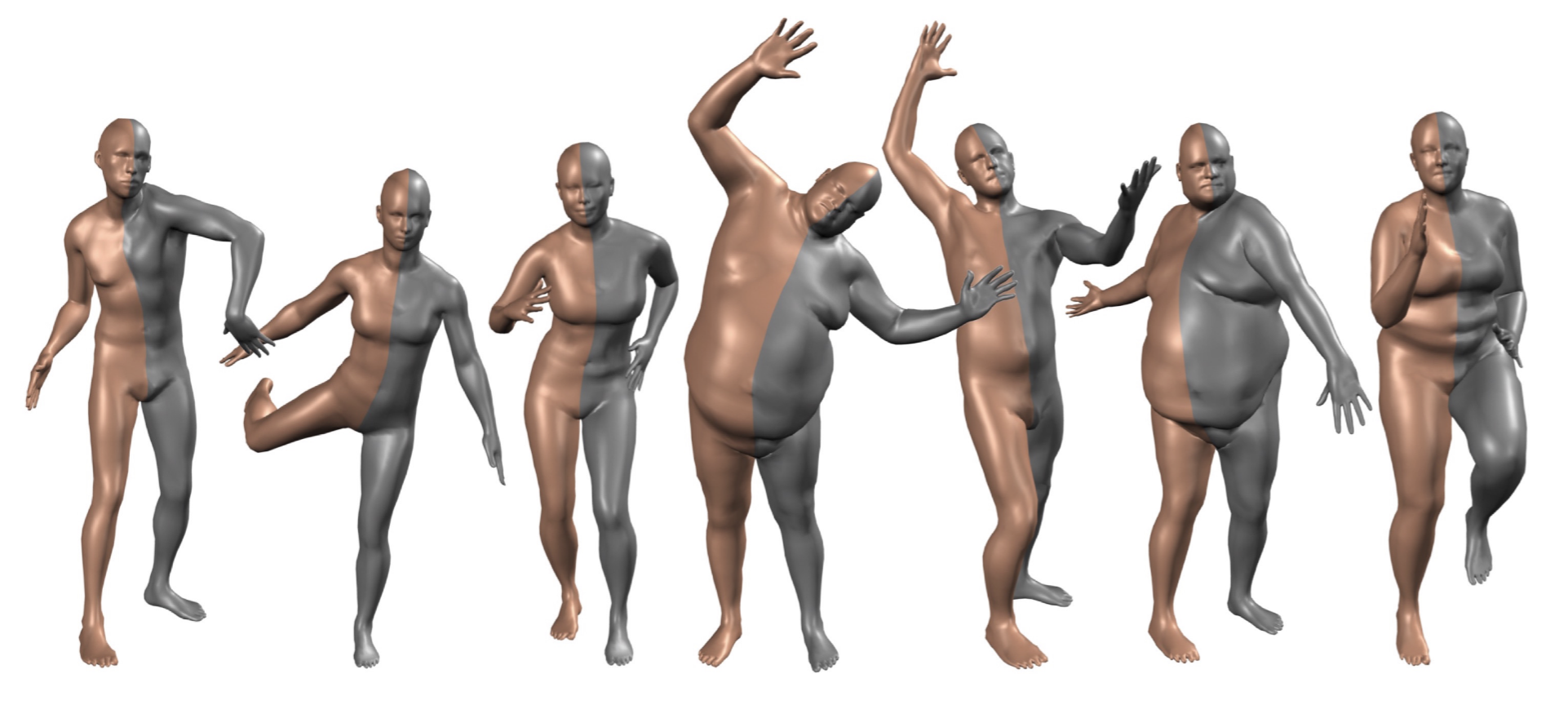

The most widely adopted model is SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear model)2, which decomposes body representations into shape parameters (\(\beta\)), usually 10 values controlling identity characteristics like height and weight, and pose parameters (\(\theta\)), that describe the skeletal structure. Within this formulation, human mesh recovery essentially becomes a regression problem: a deep neural network takes the input and acts as a feature extractor that maps visual cues directly to the SMPL parameter space.

Fig 2. Comparison between SMPL models (orange) and ground truths that SMPL parameters were learned from (gray) showing the variety of human forms that can be represented 2

While this SMPL regression has been effective in recovering accurate body pose and shape, most early HMR methods operate in a camera-centric frame that treat each frame independently, failing to recover a globally consistent human trajectory over time. Recent approaches to the gloabl human mesh recovery problem effectively extend the same parametric SMPL formulation; all approaches covered aim to output SMPL or similar parametric models.

Approaches

SLAHMR

SLAHMR attempts to solve the problem of global human mesh recovery by taking an optimization-based approach.3

Method

SLAHMR receives as input \(T\) frames of a scene with \(N\) people. First, each person \(i\)’s pose at each point in time \({\hat{P}}_t^i\) is estimated by a model known as PHALP. These estimates are used to calculate \(\mathbf{J}^i_t\), estimates locations of the joints of each human in the scene.

Fig 3. Sample pose estimates from PHALP; entire body pose is estimated but only head shown for visualization 4

Then, a SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) system called DROID-SLAM to estimate the world-to-camera transform \(\{\hat{R}_t, \hat{T}_t\}\) at each point in time, where \(\hat{R}\) is the estimated camera rotation and \(\hat{T}\) is the estimated camera translation. Since DROID-SLAM estimates camera motion without knowing the scale of the world, SLAHMR will always multiply our predicted \(T\) by a value \(\alpha\) to correct for this factor.

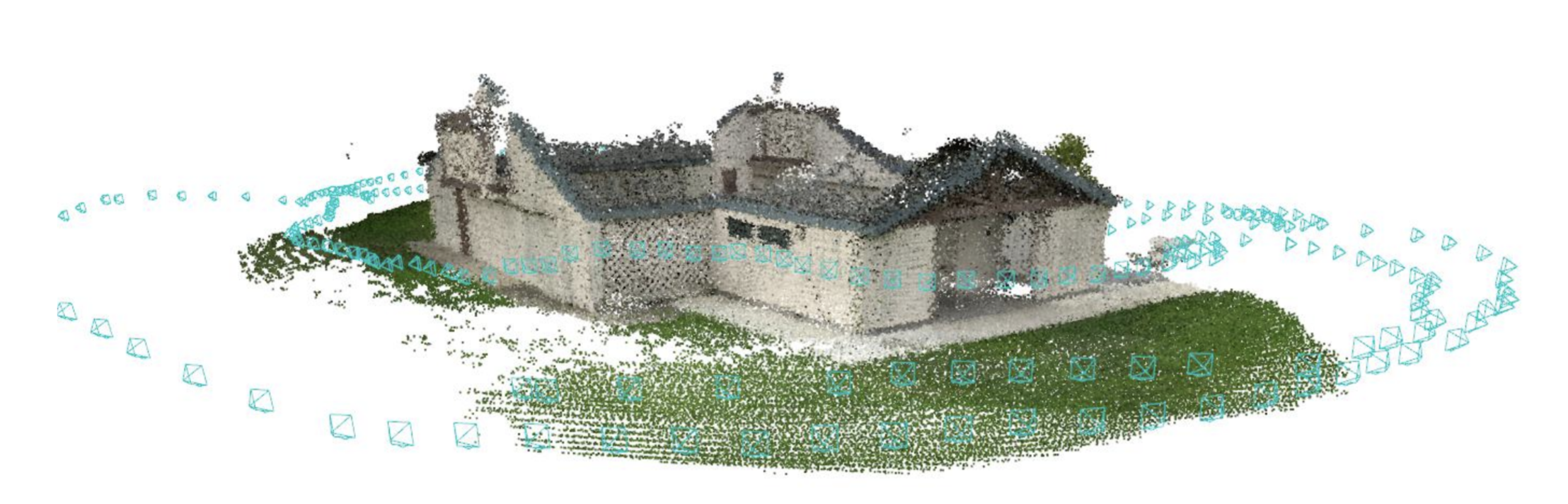

Fig 4. Sample output from DROID-SLAM; blue icons represent camera locations; outputted point map not used in SLAHMR 5

Since PHALP estimates poses for each person in the camera’s coordinate system, the goal is now to combine these pose estimations with our camera transform estimations, resulting in world-frame pose estimations.

To do this, the estimates \({\hat{P}}_t^i\) and \(\{\hat{R}_t, \hat{T}_t\}\) are used to initialize an optimization problem that we will constrain and solve. This optimization problem can be expressed as the joint reproduction loss:

\[\begin{equation} E_{\textrm{data}} = \sum_{i=1}^N \sum_{t=1}^T \psi^i_t \rho \big( \Pi_K ( R_t \cdot {}^W{\mathbf{J}}^i_t + \alpha T_t )- {\mathbf{x}^i_t} \big) \end{equation}\]This loss function represents the sum of the differences between 2D joint keypoints (\(\mathbf{x}\)) gathered from our mesh estimates and our current prediction of where that same keypoint would be on the image if a picture were taken of the predicted mesh estimate from the predicted camera location (\(R \cdot \mathbf{J} + \alpha T\)). The other terms present deal with camera projections, which are not important to understand with regards to how SLAHMR works.

Fig 5. SLAHMR Pipeline: use optimization-based approach 3

At this point, since we haven’t added many constraints, SLAHMR only optimizes the global orientation \(\Phi\) and root translation \(\Gamma\) of the human poses in a first pass. In other words, if \(\lambda\) is our learning rate:

\[\begin{equation} \min_{\{\{ {}^W{\Phi}^i_t, {}^W{\Gamma}^i_t\}_{t=1}^T \}_{i=1}^N} \lambda_{\textrm{data}} E_{\textrm{data}}. \end{equation}\]Our next pass begins optimizing \(\alpha\) as well as the human body shapes and poses. To further constrain the optimization problem gradually, we add an additional loss meant to penalize joint movements that aren’t smooth. This is a simple prior that takes advantage of the assumption that humans typically move in a smooth fashion.

\[\begin{equation} E_{\textrm{smooth}}= \sum_i^N \sum_t^T \| \mathbf{J}^i_t - \mathbf{J}^i_{t+1} \|^2. \end{equation}\]Along with a few other priors, this then allows us to optimize over all body pose parameters and our camera scale \(\alpha\):

\[\begin{equation} \min_{\alpha, \{\{ {}^WP^i_t\}_{t=1}^T \}_{i=1}^N} \lambda_\textrm{data} E_\textrm{data} + \lambda_\beta E_{\beta} + \lambda_{\textrm{pose}} E_{\textrm{pose}} + \lambda_\textrm{smooth} E_{\textrm{smooth}}. \end{equation}\]Finally, a learned prior about the distribution of human motions is introduced: the likelihood of a transition between two velocity/joint locations \(p_\theta({s}_t \| {s}_{t-1})\) is modelled as a conditional VAE where the latent \(\mathbf{z}\) represents the transition between two time states. We can use this VAE to calculate part of a new loss term, representing the likelihood of a trajectory by combining the likelihoods of transitioning between each consecutive state within the trajectory.

\[\begin{equation} E_\textrm{CVAE} = -\sum_i^N\sum_t^T \log \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{z}_{t}^i; \mu_\theta({s}^i_{t-1}),\sigma_\theta({s}^i_{t-1})). \end{equation}\]At this point, we can now optimize over entire trajectories by autoregressively calculating this loss term throughout all timesteps and adding it to all other components of our loss function.

Note that this overview only covers the most major sections of the three optimization passes in SLAHMR. There are additional portions to the final loss function not mentioned for the sake of brevity; the important part how SLAHMR optimizes in many passes due to the complexity and difficulty of the optimization problem at hand.

Performance/Shortcomings

SLAHMR improves stability over per-frame methods and handles complex camera movements significantly better than before; in comparison to PHALP alone, for instance, factoring in camera motion adds robustness to sudden camera motions when tracking subjects.

One significant weakness of SLAHMR is that it is optimization-based: this process, as detailed above, is difficult, complex, and requires multiple computation-heavy stages. This results in slow performance.

In addition, in-the-wild videos with a lot of rotational movement or co-linear motion between the human and camera can result in inconsistent trajectories. These are both areas where significant progress can be made.

TRACE

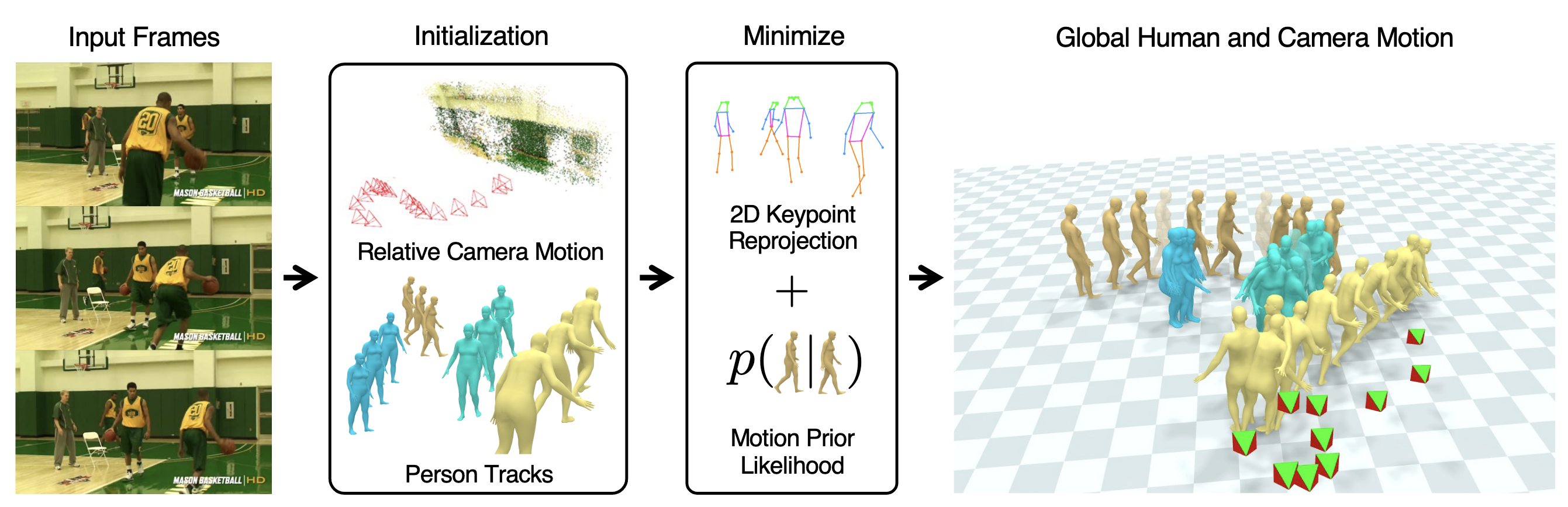

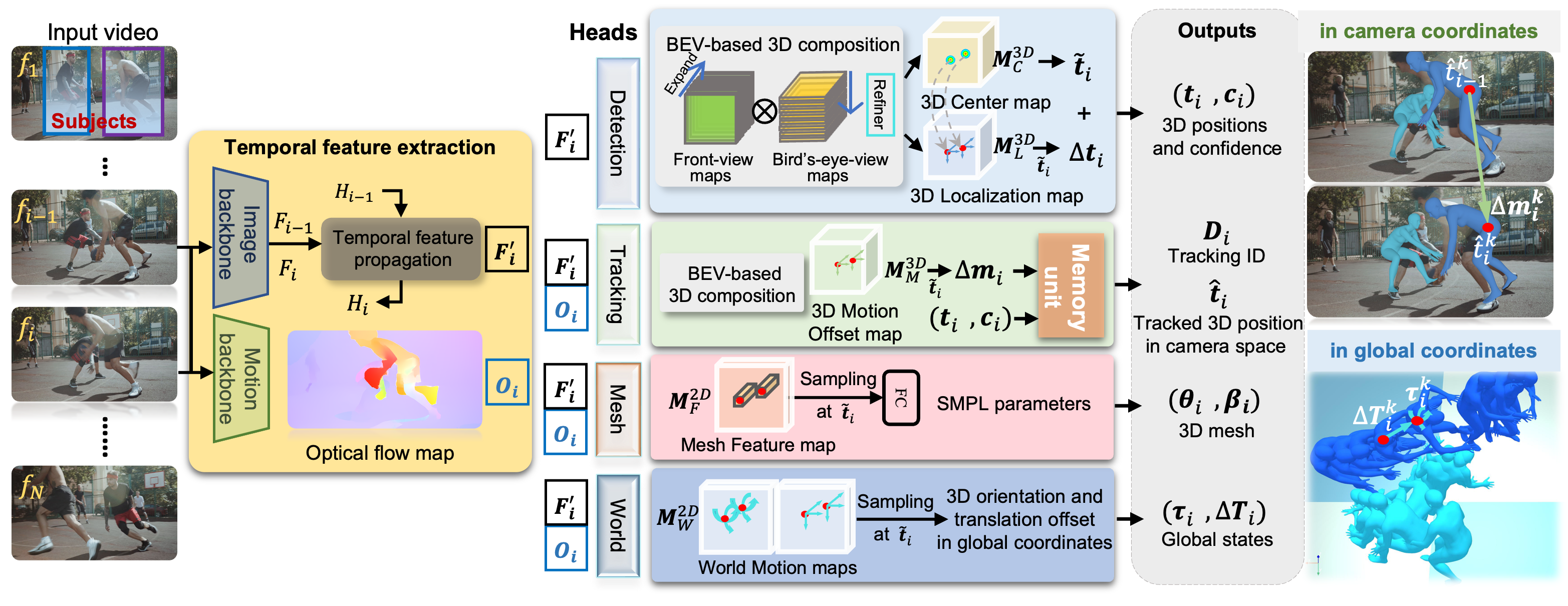

Another foundational advancement in human mesh recovery is TRACE, whose primary goal is to reconstruct movement of multiple 3D people.6 This method was the first one-stage method to track people in global coordinates with moving cameras.

TRACE achieves this by using a multiheaded network to output a novel 5D representation of space, time, and identity that enables reasoning about people in scenes. The network is divided into four branches: the detection branch, tracking branch, mesh recovery branch, and state output branch.

Fig 6. General architecture of TRACE 6

To use TRACE, the user must first annotate the first frame of the video being analyzed with information about where the \(K\) subjects they want to track are. TRACE then outputs 3D meshes and trajectory for each of these subjects from a global frame of reference.

Method

TRACE encodes the video it is given and the subject motion within it into temporal feature maps \(F_i\) and motion feature maps \(O_i\) using two parallel backbones. These feature maps are fed into the detection branch and tracking branch, respectively, which use multisubject tracking to output the 3D human trajectory in camera coordinates.

The detection branch uses the temporal feature map \(F_i\) to output a 3D center map (the detection of the subject) and a 3D localization map (the precise location of the subject). These maps are composited and combined to output 3D positions, their confidences \((t_i, c_i)\), and their offset vectors, all in the camera space.

The tracking branch uses the motion feature map \(O_i\) to to create a 3D motion offset map, which denotes the position change of each tracked subject from the previous frame to the current frame. Additionally, this branch utilizes a novel memory unit to address the problem of long-term occlusions by storing the 3D positions of each subject in previously examined frames.

Unlike SLAHMR, which uses PHALP for pose estimation and separately extracts human pose, appearance, and location in multiple stages from each video frame and combines them together, TRACE does so in an end-to-end manner. By combining the 3D motion offset map and \((t_i, c_i)\) from the detection branch, the memory unit determines subject identities and builds trajectories for each of the \(K\) subjects. Detected subjects who do not fit the output trajectories are filtered out; remaining tracking ids and their respective trajectories in the camera space are output.

Next, the mesh branch extracts SMPL formatted mesh parameters from \(F_i\) and \(O_i\) to calculate meshes for each human.

Finally, the world branch uses the 3D positions of the subjects’ in-camera coordinates to output a world motion map, which encompasses the 3D orientation and 3D translation offset of each subject in global coordinates. The combination of these is the global trajectory.

In this way, the four branches are able to recover the 3D pose, shape, identity, and trajectory of each tracked subject.

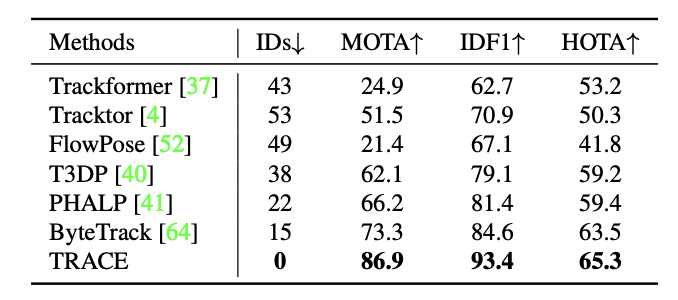

Performance/Shortcomings

TRACE is able to accurately track multiple subjects and outperforms PHALP especially when long-term occlusions occur. Furthermore, TRACE has better motion continuity (no sudden translations of the subject between frames) than other state of the art methods.

Unlike SLAHMR, which is a multi-stage optimization-based approach, TRACE combines scene information and 3D motion with its novel 5D representation to utilize the full scene context and allow for end-to-end training.

Fig 7. Tracking results of TRACE and other SOTA methods of the time on MuPoTS-3D, a dataset that contains multiperson interaction scenes with long-term occlusions 6

However, TRACE is still dependent on clean detections to output accurate trajectories and meshes. Furthermore, these meshes are not world-grounded and are relative to camera position. Finally, TRACE depends on videos as input and its multiple branches cause it to require heavy computation.

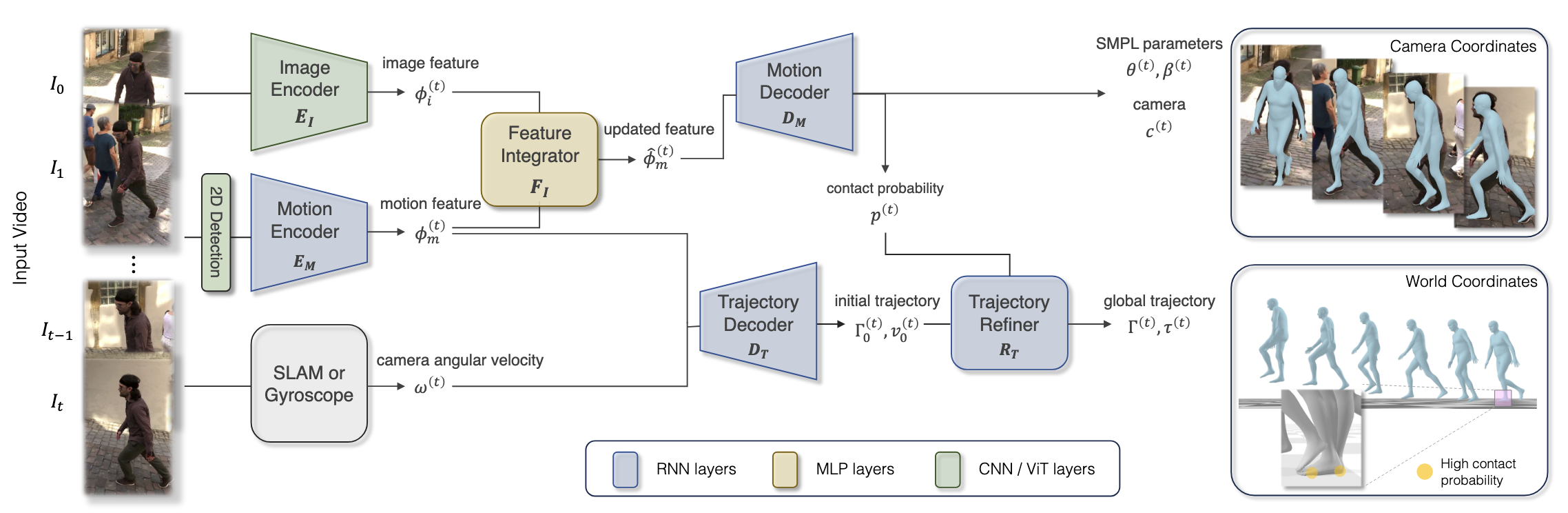

WHAM

World-Grounded Humans with Accurate Motion (WHAM) is a relatively recent approach to global human mesh recovery that targets three specific issues: global motion estimation accuracy, inference speed, and foot-ground contact.7 It builds off of both SLAHMR and TRACE, using camera and scene localization and temporal modeling, respectively. It also attempts to address the computationally expensive nature of optimization methods such as SLAHMR and the jittery video motion in regression models such as TRACE caused by challenges with handling camera, rather than subject, movement.

Method

WHAM can be divided primarily into two main tasks: motion estimation and trajectory estimation.

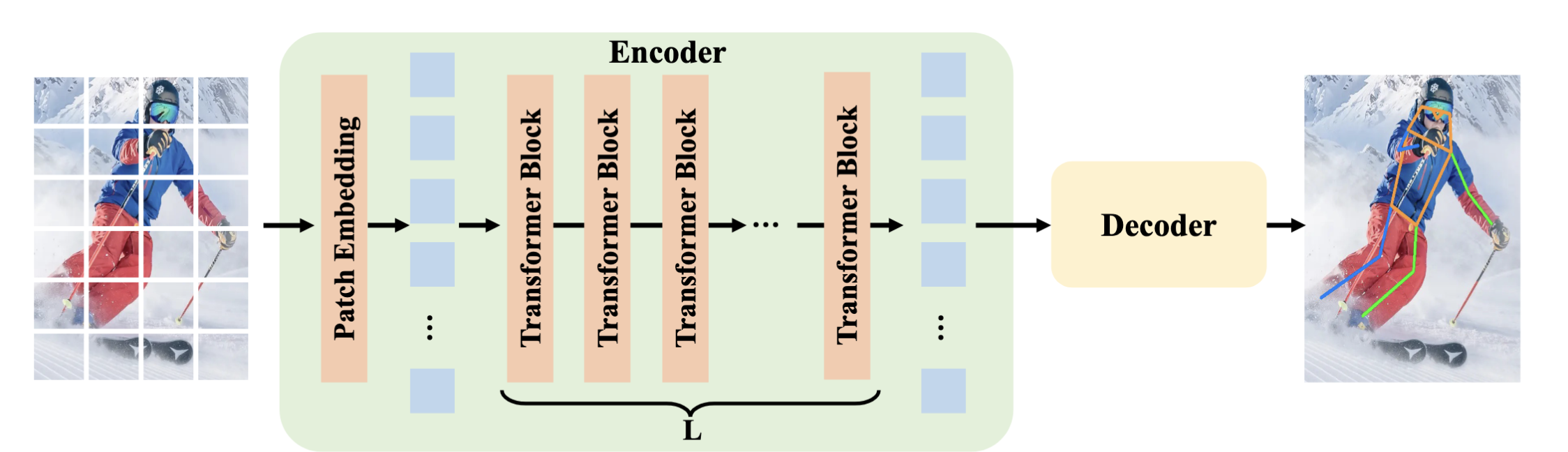

To perform motion estimation, the features of the video are first extracted. The raw video data \(\left\{ I(t) \right\}_{t=0}^{T}\) is first inputted into WHAM. ViTPose (a vision transformer based model8) is used to detect 2D keypoints \(\left\{ x_{2D}^{(t)} \right\}_{t=0}^{T}\), which are then used to extract motion features \(\left\{ \varphi^{(t)}_m \right\}_{t=0}^{T}\).

Fig 8. Architecture of the ViTPose model used for 2D keypoint extraction 8

An image encoder pretrained on AMASS (a large human motion database9) is then used to extract static image features; these static image features are integrated with the motion features to refine them.

A uni-directional RNN is used in the motion encoder, as well as the motion decoder later on, to extract the motion context from both the current and previous 2D keypoints, as well as the hidden state. The encoder is as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \varphi^{(t)}_m = E_M \left( x_2^{(0)}, x_2^{(1)}, \dots, x_2^{(t)} \mid h_E^{(0)} \right) \end{equation}\]where \(h_E^{(0)}\) is the hidden state. The keypoints are then normalized to a bounding box, and the decoder recovers the SMPL parameters as follows:

\[\begin{equation} \left( \theta^{(t)}, \beta^{(t)}, c^{(t)}, p^{(t)} \right) = D_M\!\left( \hat{\phi}_m^{(0)}, \ldots, \hat{\phi}_m^{(t)} \mid h_D^{(0)} \right). \end{equation}\]Finally, a feature integrator combines the motion context and image features through the following residual connection:

\[\begin{equation} \hat{\varphi}^{(t)}_m = \varphi^{(t)}_m + F_I \left( \text{concat} \left( \varphi^{(t)}_m , \varphi^{(t)}_i \right) \right) \end{equation}\]This outputs pixel-aligned 3D meshes that preserve temporal consistency. As we have meshes, we now need to finish our task of trajectory estimation. This can be split into two main stages.

Fig 9. WHAM architecture; note the encoder-decoder structure 7

First, the trajectory is decoded by an additional decoder \(D_T\) which predicts the global root orientation \(\Gamma^{(t)}_0\) and root velocity \(\omega^{(t)}\) from the motion feature \(\varphi^{(t)}_m\).

However, the motion feature is derived from input signals from the camera, which makes it difficult to disambiguate the human motion from the camera motion. As such, the angular velocity of the camera is concatenated with the motion feature to create a motion context that is “camera-agnostic,” meaning WHAM is compatible with both SLAM algorithms and digital camera gyroscope measurements. With this, global orientation can be predicted through the uni-directional RNN:

\[\begin{equation} (\Gamma^{(t)}_0, v^{(t)}_0) = D_T \left( \varphi^{(0)}_m, \omega^{(0)}, \dots, \varphi^{(t)}_m, \omega^{(t)} \right) \end{equation}\]WHAM then goes further to account for terrain differences to model accurate footground contact without sliding, issues that both SLAHMR and TRACE have, using a technique calledontact Aware Trajectory Refinement. First, the root velocity is adjusted to reduce foot sliding as a whole based on the probability of foot-ground contact:

\[\begin{equation} \tilde{v}^{(t)} = v^{(t)}_0 - \left( \Gamma^{(t)}_0 \right)^{-1} v^{(t)}_f \end{equation}\]However, this can lead to noisy translation if the contact and pose estimation are inaccurate, an issue resolved by using a trajectory refining network \(R_T\) to update the root orientation and velocity as needed. This trajectory refining network is then used as part of the global translation operation:

\[\begin{equation} (\Gamma^{(t)}, v^{(t)}) = R_T \left( \varphi^{(0)}_m, \Gamma^{(0)}, \tilde{v}^{(0)}, \dots, \varphi^{(t)}_m, \Gamma^{(t)}, \tilde{v}^{(t)} \right) \end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} \tau^{(t)} = \sum_{i=0}^{t-1} \Gamma^{(i)} \nu^{(i)}. \end{equation}\]which allows the model to accurately reconstruct the motion and pose of the 3D human.

Performance/Shortcomings

WHAM is quite powerful as it is now and is able to account for uneven terrain and camera movement while improving foot sliding issues, jittering, and inference speed.

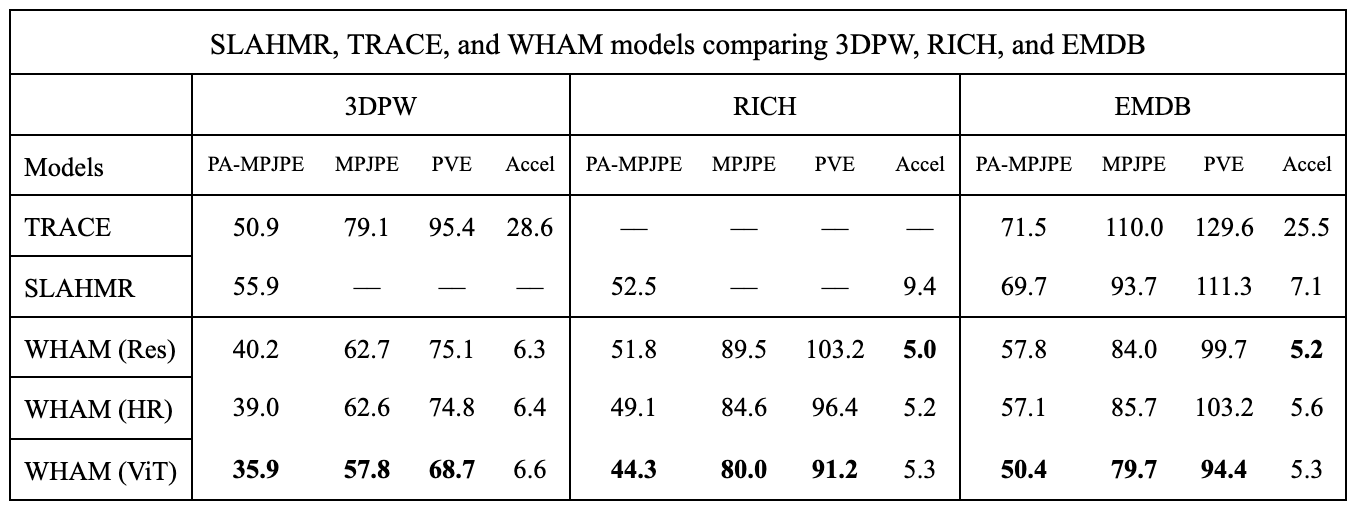

A comparison of its performance with SLAHMR and TRACE across the 3DPW, RICH, and EMDB datasets is provided in the paper discussing WHAM:

Fig 10. WHAM estimation accuracy compared with SLAHMR and TRACE across multiple datasets 7

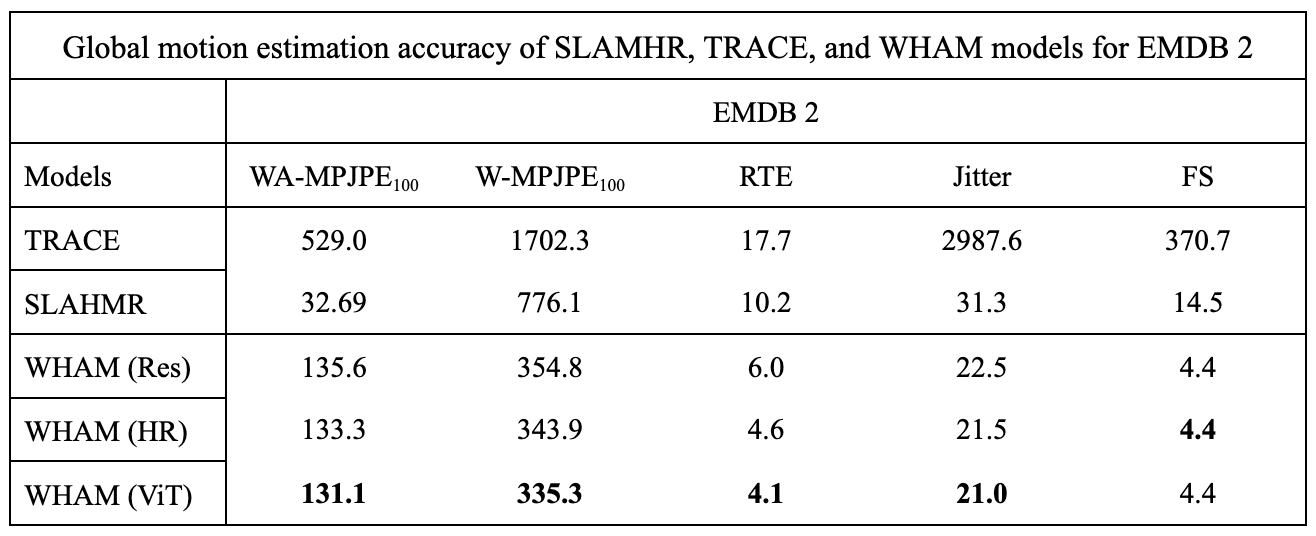

Fig 11. WHAM estimation accuracy compared with SLAHMR and TRACE on the EMDB2 dataset 7

Even with some data missing, it is clear that WHAM outperforms SLAHMR and TRACE across multiple of the datasets.

However, although WHAM has contributed many improvements to human mesh recovery and can outperform SLAHMR, TRACE, and other single-image models, it still has several limitations.

For example, because it utilizes the AMASS dataset, it has some level of motion prior bias that prevents it from fully accounting for “out-of-distribution” motions, or motions that the average person might not make regularly, such as acrobatics or injured movement, like limping. WHAM also does not fully address occlusion; even though masks are applied occasionally, motion that is blocked by other objects is not completely resolved by WHAM’s algorithm. Finally, it is still quite computationally heavy and could be further optimized for real-time applications, although it can theoretically handle them according to the paper.

Works Cited

-

Yang, et al. “OfCaM: Global Human Mesh Recovery via Optimization-free Camera Motion Scale Calibration”. 2024. ↩

-

Loper, et al. “{SMPL}: A Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model” ACM Trans. Graphics (Proc. SIGGRAPH Asia). 2015. ↩ ↩2

-

Ye, et al. “Decoupling Human and Camera Motion from Videos in the Wild” IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2023. ↩ ↩2

-

Rajasegaran, et al. “Tracking People by Predicting 3D Appearance, Location and Pose” Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2022. ↩

-

Teed, Deng. “DROID-SLAM: Deep Visual SLAM for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras” Advances in neural information processing systems. 2021. ↩

-

Sun, et al. “TRACE: 5D Temporal Regression of Avatars with Dynamic Cameras in 3D Environments” IEEE/CVF Conf.~on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2023. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Shin, et al. “{WHAM}: Reconstructing World-grounded Humans with Accurate {3D} Motion” IEEE/CVF Conf.~on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). 2024. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Xu, et al. “ViTPose: Simple Vision Transformer Baselines for Human Pose Estimation”, Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. 2022. ↩ ↩2

-

Mahmood, et al. “{AMASS}: Archive of Motion Capture as Surface Shapes” International Conference on Computer Vision. 2019. ↩