Comparison of Approaches to Human Pose Estimation

This paper presents a comparative analysis of prominent deep learning approaches for 2D human pose estimation, the task of locating key anatomical joints in images and videos. We examine the core methodologies, architectures, and performance metrics of three seminal models: the bottom-up OpenPose (2019), the top-down AlphaPose (2022), and the top-down ViTPose (2022), which leverages a Vision Transformer backbone. We then introduce Sapiens (2024), a recent foundation model that pushes state-of-the-art accuracy by adopting a massive MAE-pretrained transformer, high-resolution inputs, and significantly denser whole-body keypoint annotations. The comparison highlights the change from complex, manual systems like OpenPose, moved to efficient refining methods with AlphaPose, and now powerful but simple transformer models like ViTPose and Sapiens.

- 1. Overview of Human Pose Estimation

- 2. Datasets

- 3. OpenPose

- 4. AlphaPose

- 5. ViTPose

- 6. Comparison

- 7. Sapiens

- 8. Conclusion

- 9. References

1. Overview of Human Pose Estimation

1.1. Objective

Human pose estimation is the process of identifying key human joints (known as keypoints) in an image or video to understand a person’s posture and movement. These capabilities enable a wide range of applications, from robotics, physiotherapy, virtual shopping applications, animation and human–computer interaction. In a typical pose-estimation pipeline, the model takes an image of a person (or multiple people) as input, detects keypoints across the body, and uses them to construct a skeleton representation that captures the person’s pose.

1.2. Challenges

Some of the challenges to human pose estimation include occlusions, which means that algorithms can struggle to infer the location of joints if they are hidden by other bodies or surroundings. Other challenges include variations in images from different camera angles, amount of people in the scene, and differences in human appearance. Additionally, poses occur in various scenarios inculding, sports and colleges etc. If not trained on these scenarios a model could fail on new data. Lighting and weather conditions can also change models. It is important that models think about all these challenges to have high accuracies.

1.3. Approaches

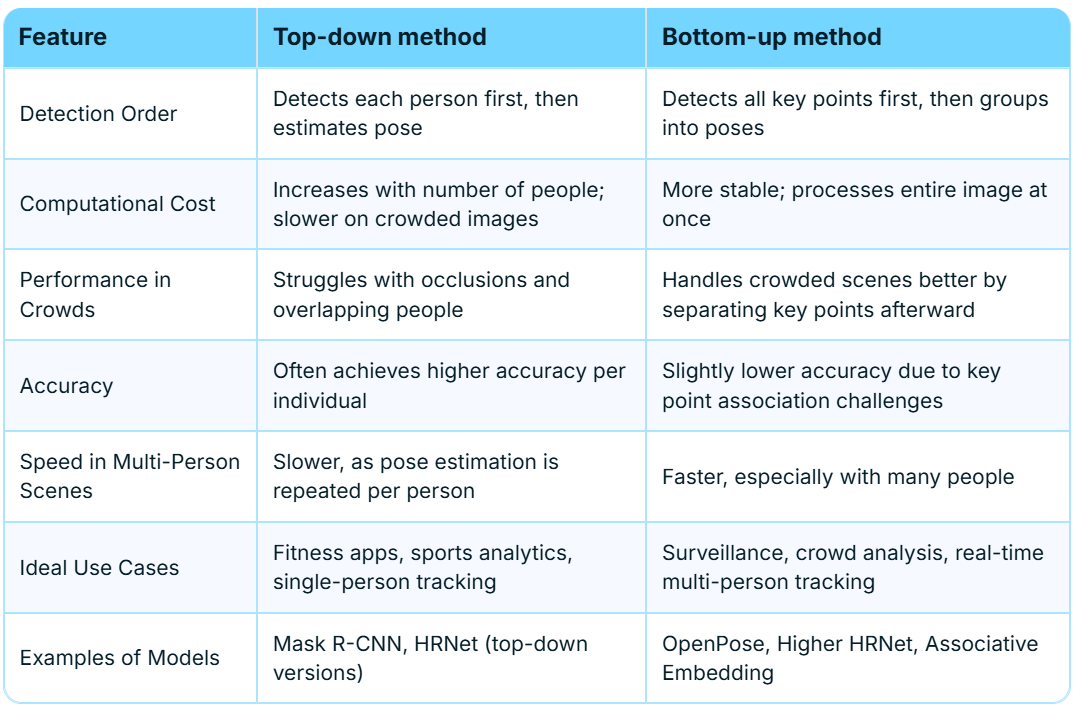

There are two main approaches that define the way a human pose model estimates and figures out key points to make a skeleton. The first method known as the topdown method is the process of detecting the person first using bounding boxes and then estimating the pose by figuring out their keypoints.

The second method is known as the bottom-up approach. With this approach all key-points are detected first. Then the keypoints are grouped into different poses.

This method is usually faster than the top-down because pose estimation doesn’t have to be repeated per person. It is also usually faster at handling crowded scenes because it doesn’t rely on a separate person detector.

Table 1: Comparison of top-down and bottom-up human pose estimation approaches [5].

Table 1: Comparison of top-down and bottom-up human pose estimation approaches [5].

1.4. Current Methods

Some prominent models of human pose estimation are OpenPose from 2019, AlphaPose from 2022, and ViTPose from 2022. There are many comparisions and contrasts to how they figure out human poses. A model that improved these prior models is known as Sapiens (2024).

2. Datasets

2.1. COCO (Microsoft)

The various pose estimate models we explored all were evaluated on MS COCO, a large-scale dataset widely used for human pose estimation, providing images annotated with 17 keypoints for each person, including joints like the nose, eyes, shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles. These detailed keypoint annotations allow models to learn to detect and predict human poses in complex, real-world scenes with multiple people. Its large-scale, diverse dataset makes it a standard benchmark for evaluating pose estimation algorithms.

3. OpenPose

3.1 Approach

OpenPose addresses the problem of localizing anatomical keypoints by focusing on finding body parts of individuals first in a bottom up approach. However, this presents issues with multiperson pose estimation. This paper presents an efficient method for multiperson pose estimation by introducing part affinity field refinement to maximize accuracy and changes to the network and adds on foot keypoint detection.

The pipeline is as follows: the system takes a color image as input and produces the 2D locations of anatomical keypoints for each person in the image, 2D confidence maps and 2D vector fields are created and are then parsed by greedy inference to output the 2D keypoints for all people in the image. The 2D vector fields are used in part affinity fields that encode the degree of association between parts.

3.1.1. Part Affinity Fields

A PAF is a 2D vector field that represents the direction and presence of a limb. Each also has a PAF based association score for each possible pairing which the greedy parser uses to link parts in human skeletons. PAFs are important because in comparison to before, they provide continuous spatial coverage, encode orientation, and enable multi-person association without costly global optimization.

3.2. Architecture

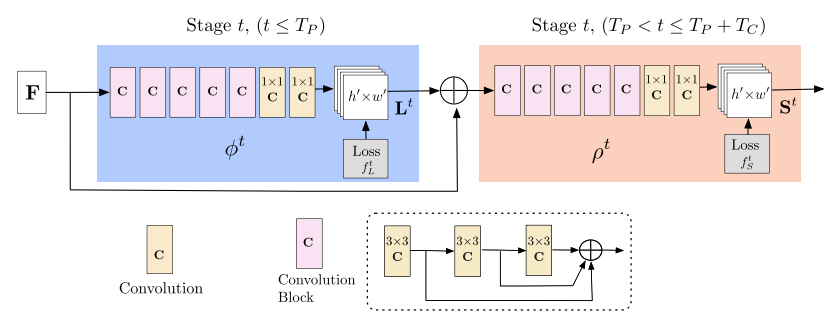

Affinity fields are iteratively predicted and encode part-to-part association and detection confidence maps. The iterative prediction architecture refines predictions over successive stages with intermediate supervision at each stage. In order to reduce the number of operations while the network depth increases, there are three consecutive 3×3 kernels whose outputs are concatenated. To keep both lower level and higher level features, the number of non-linearity layers is tripled.

The image is analyzed by a CNN which generates a set of feature maps that is input to the first stage. It uses a multi-stage, dual branch CNN, with a VGG-19 backbone.

3.2.1. Feature Extraction

The first 10 convolutional layers of VGG-19 extract F=ϕVGG(I), which produces a shared feature map used by both branches.

3.2.2. Multi-Stage Prediction

The first stage inputs consist of the feature maps F to produce PAFs \(L^{t} = \phi ^{1}(F)\).

These subsequent stages take predictions from the previous stage and the original image features F and concatenate them to produce refined predictions. The same process with PAF stages is done for confidence map detections, starting with the most updated PAF prediction.

\[L^{t} = \phi ^{t}(F, L^{t-1}), \forall 2\leq t\leq T_{p}\] \[S^{T_{P}} = \rho ^{t}(F,L^{T_{P}}), \forall t=T^{P}\] \[S^{t} = \rho ^{t}(F, L^{T_{P}}, S^{t-1}), \forall T_{p}< t\leq T_{P}+T_{C}\] Figure 1: Multi-stage CNN architecture for OpenPose[1].

Figure 1: Multi-stage CNN architecture for OpenPose[1].

3.3. Training Strategy

The loss function is given as follows for the PAF branch at stage ti and confidence map branch at stage \(t_k\) where * marks the ground truth for each of them:

\[f_{L}^{t_{i}}=\sum_{c=1}^{C}\sum_{p}^{}W(p)\cdot \left\| L_{c}^{t_{i}}(p)-L_{c}^{*}(p)\right\|_{2}^{2}\] \[f_{S}^{t_{k}}=\sum_{j=1}^{J}\sum_{p}^{}W(p)\cdot \left\| S_{j}^{t_{k}}(p)-S_{j}^{*}(p)\right\|_{2}^{2}\]L2 loss is used between the estimated predictions and the ground truth maps and fields at the end of each stage. In order to address the problem of some datasets not completely labeling all people, the loss is weighted spatially. A binary mask is also used in order to avoid penalizing the true positive predictions during training. The immediate supervision at each stage addresses the vanishing gradient problem by replenishing the gradient periodically. OpenPose is also significant because it is the first model to include foot keypoints, ultimately being the first full-body pose dataset for whole body estimation.

3.3.1. Part Association Strategy

After the detected body parts points are generated, they need to be assembled to form an unknown number of people. To do this, it requires a confidence measure of association for each pair of body part detections and one possible method is to identify an additional midpoint between each pair of parts on a limb and check for its incidence between candidate part detections. A challenge, however, is that when people are bunched together, false associations are very likely to occur because of the fact that this representation only encodes the position and not orientation of the limbs and it reduces the region of support of a limb to a single point. PAFs address these limitations by preserving both the location and orientation information for each pixel. Each pair of associated body parts has a PAF joining them together.

For a single limb, if a point p lies on the limb then the value of the PAF at p is a unit vector that points to the connecting body keypoint and to all other points, the vector is zero-valued. During testing, association between candidate part detections is measured by computing the line integral over the corresponding PAF along the line segment connecting the candidate part locations. The predicted PAF is sampled to measure the confidence in their association.

3.3.2. Multi-Person Parsing

With multiple people, there is a large set of part candidates for possible limbs so each candidate limb is scored using the line integral computation mentioned earlier then the problem of finding the optimal parse corresponds to a K-dimensional matching problem that is known to be NP-Hard. This paper presented a greedy relaxation algorithm where first the candidates are obtained and the problem is reduced to a maximum weight bipartite graph matching problem with each possible connection defined as input. Nodes of the graph are body part detection candidates and edges are possible connections between candidates and are weighted by the part affinity aggregate. Matching occurs in a way such that no two edges share a node with a goal of maximizing the weight for chosen edges.

3.4. Performance

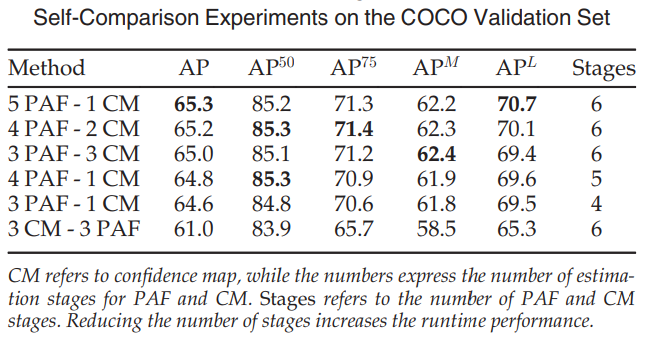

Table 2: OpenPose performance on the COCO validation set[1].

Table 2: OpenPose performance on the COCO validation set[1].

Foot AP: ~78% AP (internal dataset)

Speed: 20–30 FPS on GTX 1080Ti / Titan X

OpenPose is scalable because the runtime is independent of the number of people. Detection is per-pixel, not per person and runtime is of complexity O(H×W×D) where D is network depth.

Some of the qualitative strengths is that it has excellent performance in crowded scenes, accurate limb orientation because of use of the PAFs, and is robust to partial occlusion.

3.4.1. Limitations

Some of the limitations include PAF matching struggles with severe occlusion, performance decreasing for very small-scale people, hands and face detection increasing memory demand, and greedy matching can yield suboptimal global pose graphs.

There is also a trade-off between speed and accuracy because with bottom up approaches, lower accuracy is caused by limited resolution because the whole image is fed at once.

4. AlphaPose

4.1. Approach

AlphaPose is a top-down framework that jointly performs human pose estimation and tracking in real time. To support camera streams in addition to traditional batch image and video input, AlphaPose emphasizes model accuracy as well as inference speed. Previous top-down approaches have shown, on average, higher accuracy than their bottom-up counterparts at the expense of slower inference. AlphaPose advanced human pose estimation and tracking on both fronts, proposing four novel techniques to improve the accuracy of existing top-down methods and a multithreaded five-module pipeline to decrease inference time.

The top-down approach to multiperson pose estimation is two-staged and sequential, with an initial human detector to identify individuals and a successive human pose estimator to locate keypoints per individual. AlphaPose treats human pose tracking as a third stage that can be run in parallel to the second stage and that can optionally share weights with the human pose estimator for faster inference. In addition to designing a system for real-time pose estimation and tracking, AlphaPose introduces FastPose, a CNN-based human pose estimator with competitive results to existing models.

4.2. Proposals

4.2.1. Symmetric Integral Keypoint Regression (SIKR)

Keypoint localization is a fundamental task in human pose estimation and has historically relied on heatmap-based methods. However, heatmaps are discrete structures that are bound to spatial dimensions and consequently face quantization error. To allow keypoint predictions to fall off-grid, AlphaPose favors integral regression, also known as soft-argmax, on a learned probability heatmap for every keypoint. Unaligned coordinates promote greater precision in learned predictions, but the traditional formulation of integral regression faces the size-dependent keypoint scoring and asymmetric gradient problems. AlphaPose proposes a two-step heatmap normalization method and an amplitude symmetric gradient function to address these two problems respectively.

4.2.1.1. Two-Step Heatmap Normalization

AlphaPose relies on probability heatmaps for keypoint localization, and probability heatmaps must satisfy the properties of a probability mass function. Notably, \(\sum_x p_x = 1\), where \(x\) is the absolute position of a pixel, \(p\) is the probability heatmap for the given keypoint, and \(p_x\) is the value of the heatmap at position \(x\). This is a common use case for the softmax function, and previous integral regression approaches have used softmax as a one-step normalization for the probability heatmap.

The probability heatmaps in AlphaPose primarily inform the prediction of keypoint positions, but past approaches have also taken the greatest value of the probability heatmap as keypoint confidence for mAP calculations. Critically, global normalization under softmax renders the magnitude of the greatest heatmap value inversely proportional to the relative size of the keypoint. Across heatmaps, smaller keypoints have, on average, more spatially concentrated probabilities than larger keypoints and have thus produced higher confidence scores than their larger counterparts within past approaches.

To correct for size-dependent keypoint scoring, AlphaPose explicitly avoids global normalization prior to calculating keypoint confidence. Instead, AlphaPose generates a confidence heatmap as an intermediate step to the probability heatmap calculation at each timestep. The confidence heatmap is normalized element-wise via the sigmoid function from raw logit values, and keypoint confidence is taken as the greatest value in the revised confidence heatmap. The probability heatmap is then taken simply as \(p_x = \frac{c_x}{\sum_x c_x}\).

4.2.1.2. Amplitude Symmetric Gradient

In the context of integral regression, an asymmetric gradient simply refers to a gradient that violates translation invariance — that is, a pixel-wise gradient function whose magnitude depends on the absolute position of a pixel rather than its relative position to the ground truth.

Under integral regression, the predicted position of a given keypoint is given as

\(\hat{\mu} = \sum_x x \cdot p_x\).

The resulting \(\hat{\mu}\) is a traditional weighted sum that notably depends on \(x\). Treating the L1 norm between the predicted and ground-truth keypoint positions as loss, the dependence on \(x\) (back)propagates to the gradient of the loss function used to update the probability heatmap:

\(\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}_{\text{reg}}}{\partial p_x} = x \cdot \text{sgn}(\hat{\mu} - \mu)\),

where \(\mu\) is the ground-truth of the keypoint position.

To preserve translation invariance, AlphaPose introduced an amplitude symmetric gradient function to approximate the true gradient. This approximation is given as

\(\delta_{\text{ASG}} = A_{\text{grad}} \cdot \text{sgn}(x - \hat{\mu}) \cdot \text{sgn}(\hat{\mu} - \mu)\),

where \(A_{\text{grad}}\) is a scalar constant set to ⅛ of the heatmap size for stability as derived through Lipschitz analysis. Note that this gradient replaces \(x\) from the original gradient equation with \(A_{\text{grad}} \cdot \text{sgn}(x - \hat{\mu})\), eliminating the direct dependence of the gradient on \(x\) in favor of its relative position to the predicted keypoint.

4.2.2. Part-Guided Proposal Generator (PGPG)

By nature of a two-stage approach, the human pose estimator in a top-down framework depends on the distribution of bounding boxes produced by the human detector. Past papers have assumed that a pretrained pose estimator will generalize to the second stage of multiperson pose estimation, but the ground-truth bounding boxes in labeled single-person datasets inevitably differ from the bounding boxes produced by a human detector during inference. This applies to whole-body pose estimation as well — the distribution of the face and hands relative to ground-truth boxes of part-only datasets will differ from their distribution relative to whole-body boxes as produced by a human detector. Without further adjustment, ground-truth boxes then prove inadequate for generalization. This motivates the training of the pose estimator on a dataset that simulates the distribution of bounding boxes generated by the human detector, rather than on a dataset with exclusively ground-truth bounding boxes.

To model the generated bounding box distribution given the part (or whole-body) classification \(p\) of a training image, AlphaPose introduces a part-guided proposal generator to learn the probability function

\[P(\delta x_{\min}, \delta x_{\max}, \delta y_{\min}, \delta y_{\max} \mid p)\]where \(\delta x_\text{min}\) is the leftmost offset of a generated bounding box relative to ground truth, \(\delta x_\text{max}\) is the rightmost offset of the generated bounding box relative to ground truth, \(\delta y_\text{min}\) is the topmost offset relative to ground truth, and \(\delta y_\text{max}\) is the bottommost offset relative to ground truth.

To learn this function, AlphaPose trains the proposal generator with samples from the Halpe-FullBody dataset in which the body, face, and hand annotations are separated. For every sample, the generator is tasked in predicting the whole-body bounding box when given a part in isolation, with a loss calculated against the ground-truth bounding box of the full body. Once trained, AlphaPose uses the generator, conditioned on part (and thus dataset), to augment the training dataset for the pose estimator. Experiments performed with the PGPG module show that such an approach indeed better simulates bounding-box input at inference time and increases mean average precision.

4.2.3. Parametric Pose Non-Maximum Suppression (Pose-NMS)

Because AlphaPose seeks to avoid the early commitment problem of top-down approaches, the framework delays NMS from the human detection stage to the pose estimation stage. This choice results in the generation of redundant pose estimations. AlphaPose advances Pose-NMS as a mechanism to reduce proposal redundancy by defining confidence and similarity metrics for poses.

AlphaPose precalculates pose confidence as the greatest value of the keypoint confidence map from the discussion of two-step heatmap normalization. Pose similarity is derived from pose distance, which is defined as the following soft matching function:

\[P(\delta x_{\text{min}}, \delta x_{\text{max}}, \delta y_{\text{min}}, \delta y_{\text{max}} \mid p)\]Here, \(K_{\text{Sim}}(P_i, P_j \mid \sigma_1)\) will be close to 1 when pose P_i and pose P_j both have high confidence scores and will softly count the number of matching keypoints between the two poses. \(H_{\text{Sim}}(P_i, P_j \mid \sigma_2)\) is large when the spatial distance between corresponding keypoints between P_i and P_j are large.

By iterating through poses in order of decreasing confidence and eliminating poses with a similarity greater than the elimination threshold \(\eta\), delayed NMS enables AlphaPose to select more optimal poses than its predecessors.

4.2.4. Pose Aware Identity Embedding

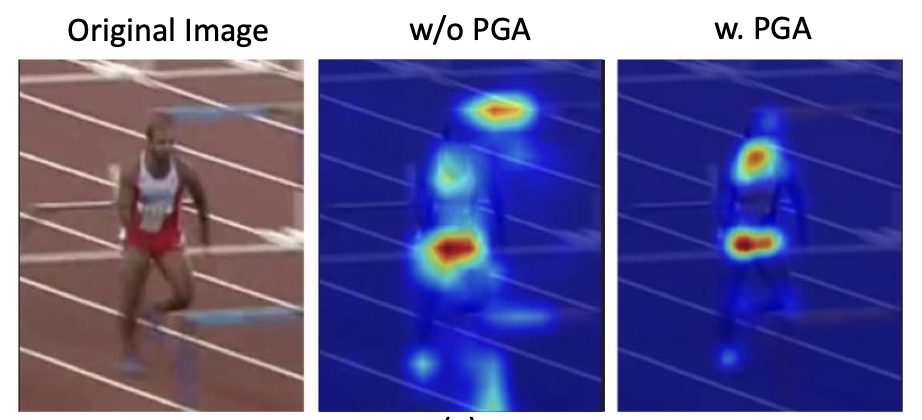

Provided with a bounding box from the human detector, keypoint heatmaps from the human pose estimator, and an identity embedding from the pose-guided attention (PGA) module, the multi-stage identity matching (MSIM) algorithm encapsulates the core pose tracking logic in AlphaPose.

The PGA module in particular passes keypoint heatmaps from the pose estimator through a convolution layer to generate an attention map. Notably, this attention map has low activations in regions of low keypoint probability and high activations in regions of high keypoint probability. The map \(m_A\) is used to weigh an individual’s re-ID feature map \(m_\text{id}\) as calculated from the bounding box of the human detector, effectively decreasing the impact of background elements on human pose tracking. The weighted re-ID feature map is given as

\(m_\text{wid} = m_\text{id} * m_A + m_\text{id}\),

where the \(*\) operation represents element-wise matrix multiplication. The adjusted identity embedding \(\text{emb}_\text{id}\) is finally passed through a fully-connected layer with output dimension 128 before use in the MSIM module.

The introduction of the PGA module has shown quantitative and qualitative improvements to model attention alike.

Figure 2: Comparison of AlphaPose attention with and without the PGA module[2].

Figure 2: Comparison of AlphaPose attention with and without the PGA module[2].

4.3. Inference Pipeline

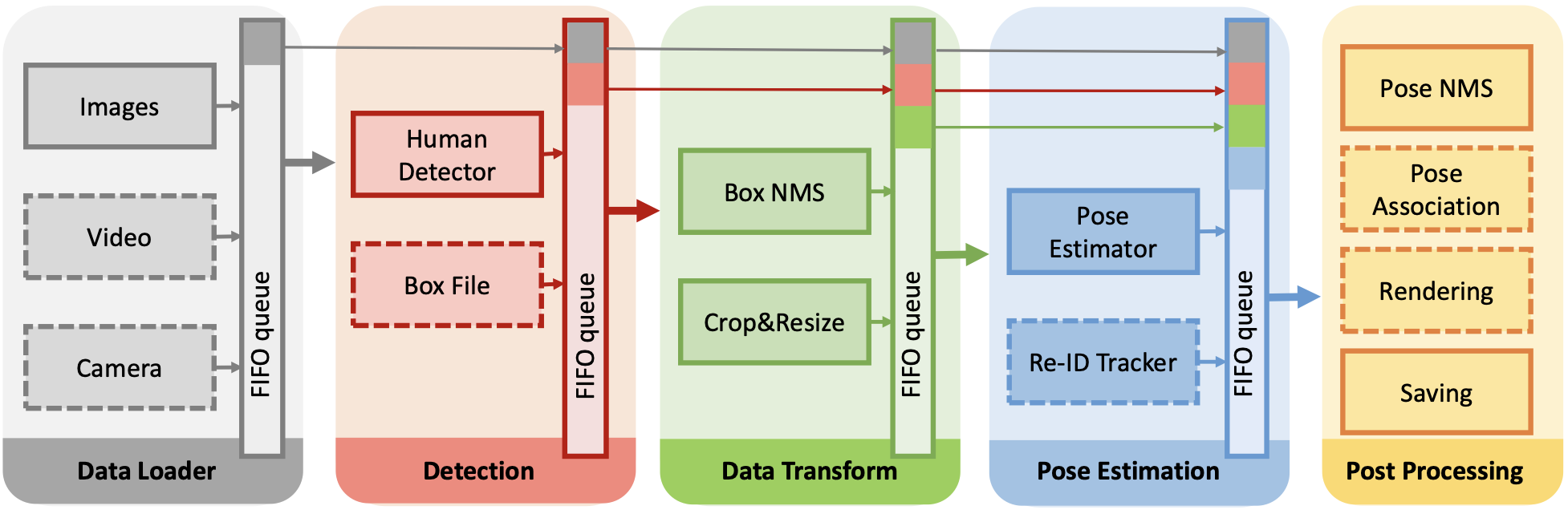

Figure 3: Five-module inference pipeline for AlphaPose. Optional components within each module marked with dashed borders[2]

Figure 3: Five-module inference pipeline for AlphaPose. Optional components within each module marked with dashed borders[2]

4.3.1. Data Loader

As an I/O-intensive module, the data loader is an independent module in the processing pipeline. The system accepts any of three forms of visual input: images, videos, or camera streams. The loader module places received input in a queue to be pulled by the detection module.

4.3.2. Detection

AlphaPose has been successfully integrated with a number of existing off-the-shelf human detectors, including YOLOX, YOLOV3-SPP, EfficientDet, and JDE as trained on the COCO dataset. Due to domain similarity, these pretrained models prove adequate and do not require explicit finetuning for use with AlphaPose. Bounding boxes are given a confidence of 0.1 to increase the recall rate of pose proposals.

4.3.3. Data Transform

The data transform module performs traditional box NMS on the bounding boxes produced by the human detector, as well as basic image cropping and resizing before transfer to the pose estimator.

4.3.4. Pose Estimation

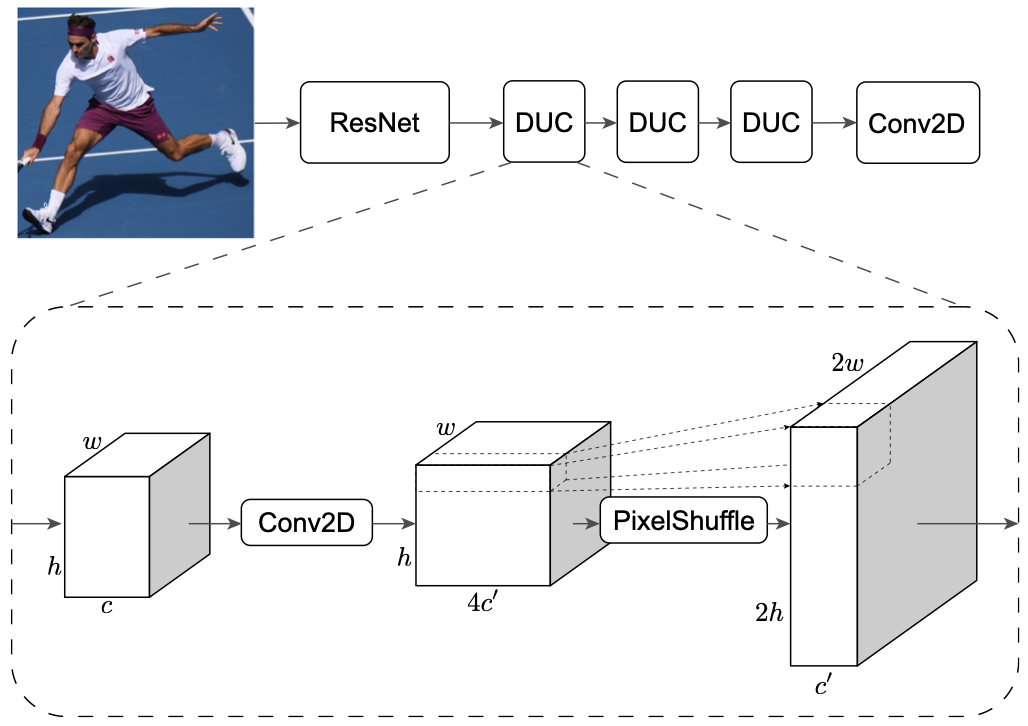

Figure 4: Aggressive upsampling architecture of FastPose[2].

Figure 4: Aggressive upsampling architecture of FastPose[2].

AlphaPose proposes the FastPose human pose estimator, built on a ResNet backbone for feature extraction. The output of ResNet is passed successively through three dense upsampling convolution (DUC) modules, each of which contains a Conv2D layer followed by a PixelShuffle operation to double each spatial dimension of the feature map. Aggressive upsampling improves the representation of lower-resolution keypoints in later layers. A final 1×1 Conv2D layer generates heatmaps for each keypoint.

Due to the various proposals set forth by the paper and the flexibility of the ResNet backbone, AlphaPose introduced a number of FastPose variants. FastPose50-hm uses heatmap-based localization with a ResNet-50 backbone as a performance baseline. FastPose50-si and FastPose152-si use symmetric integral regression, and FastPose50-dcn-si and FastPose101-dcn-si use an additional deformable convolution layer in the ResNet-50 and ResNet-101 backbones to learn adaptive offsets to their receptive fields with minimal computational overhead. All -si models have -hm counterparts, all -dcn models have non-dcn counterparts, and all 101 and 152 models have 50 counterparts for model comparison.

Like the detection module, the pose estimation module supports one of many estimators, including SimplePose, HRNet, and the many variants of FastPose. The module provides the re-ID tracker as an optional branch on the pose estimator as well.

4.3.5. Post Processing

As the last module in the inference pipeline, the post processing module runs Pose-NMS on generated keypoint heatmaps to eliminate redundant poses and saves finalized pose estimations.

4.4. Training

4.4.1. Datasets

FastPose was trained and evaluated on the existing COCO 2017, COCO-WholeBody, 300Wface, FreiHand, and InterHand datasets, as well as the newly annotated Halpe-FullBody dataset introduced for AlphaPose. The pose tracking branch was trained on the PoseTrack-2018 dataset and evaluated on both the PoseTrack-2017-val and PoseTrack-2018-val datasets.

4.4.2. Details

The model was trained with a batch size of 32 images of size 256×192 for 270 epochs with an Adam optimizer and an initial learning rate of 0.01. Each batch was sampled equally from the Halpe-FullBody dataset, the COCO-WholeBody dataset, and the pooled 300Wface and FreiHand datasets. The learning rate was decayed by a factor of 0.1 on epochs 100 and 170, the PGPG module was applied after epoch 200, and only the re-ID branch was finetuned between epochs 270 and 280 with learning rate 1e-4.

4.5. Evaluation

4.5.1. Performance

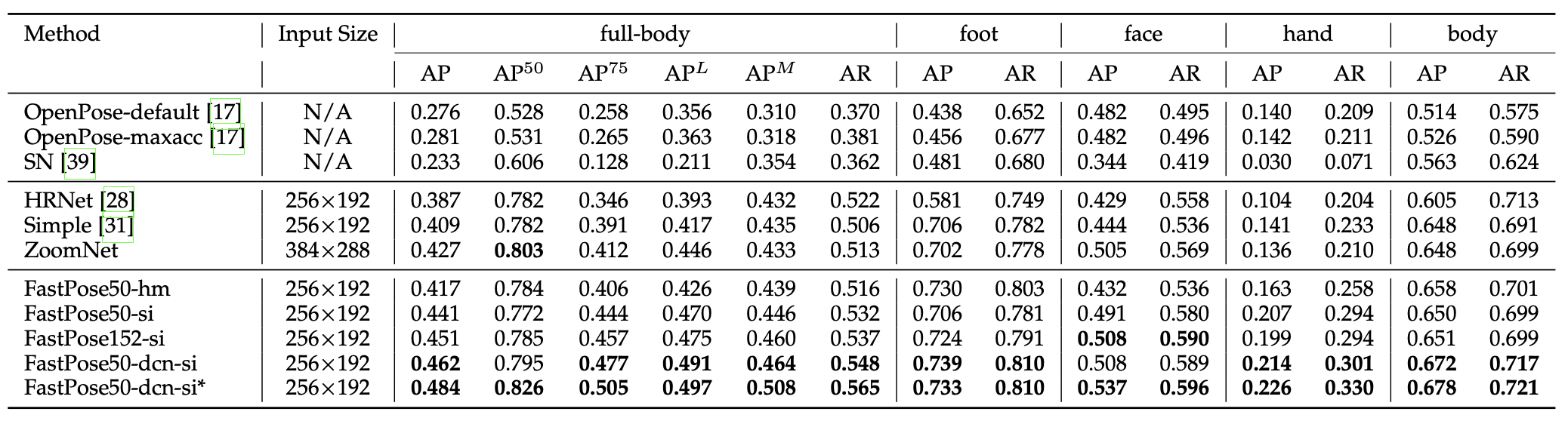

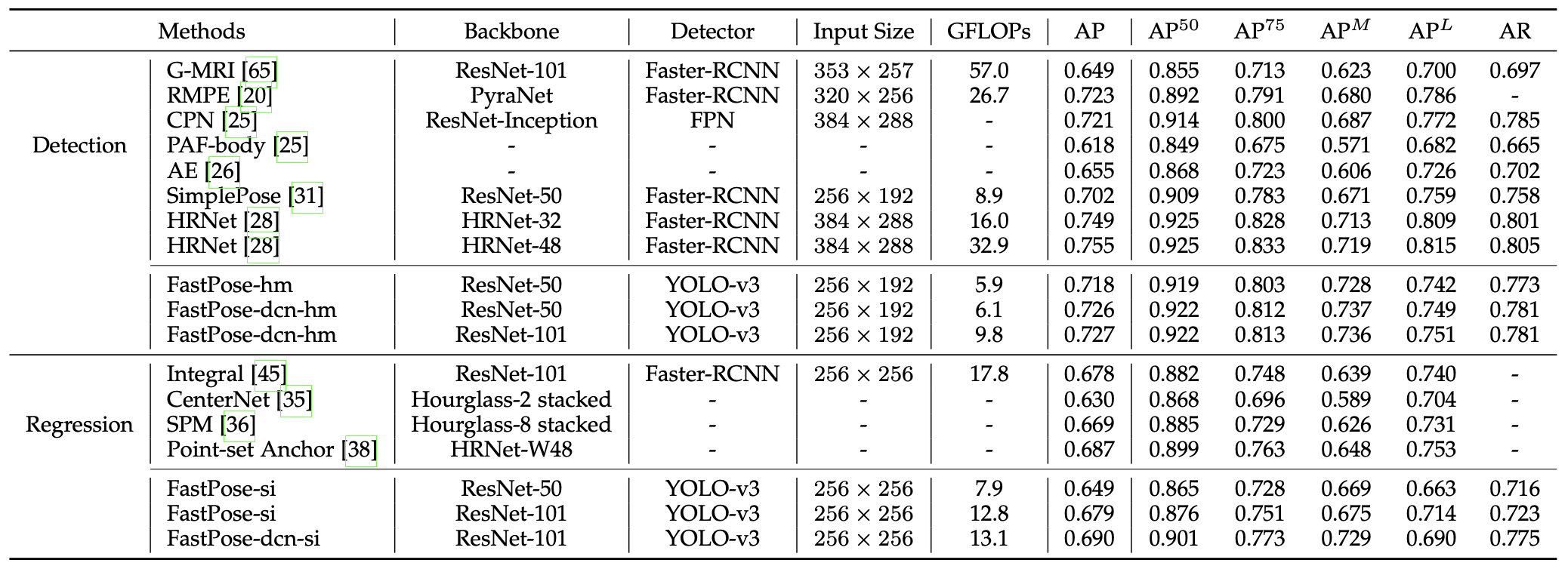

Table 3: Comparison of model performance on the Halpe-FullBody dataset[2].

Table 3: Comparison of model performance on the Halpe-FullBody dataset[2].

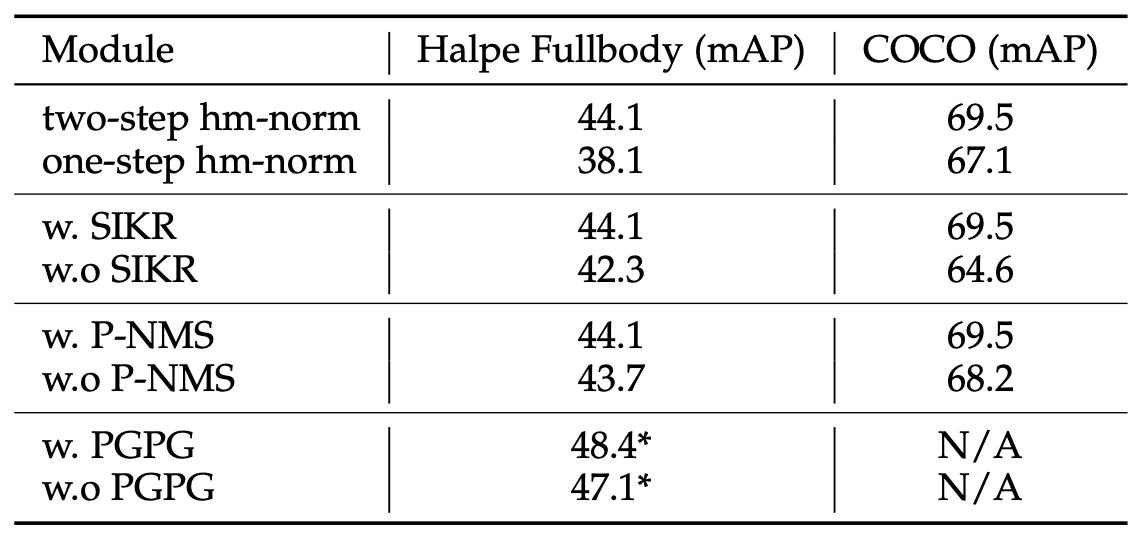

Symmetric integral regression variants of FastPose yielded a 5.7% relative increase in mAP to their heatmap-based counterparts, largely due to improved performance near the face and hands. The 2.4 increase in mAP suggests the effectiveness of symmetric integral regression in parsing dense keypoint localizations. With a combined 7.8 mAP contribution to performance on the Halpe-FullBody dataset and a combined 7.3 mAP contribution to performance on the COCO dataset, ablation studies suggest the same. FastPose additionally demonstrates higher accuracy and fewer GLOPs for the face and hands than other competitive models on the COCO-WholeBody dataset.

The Pose-NMS and PGPG modules prove integral to the performance of FastPose as well. Pose-NMS accounts for a 0.4 mAP increase for the Halpe-FullBody dataset and a 1.3 mAP increase for the COCO dataset, whereas the PGPG module accounts for a 1.3 mAP increase for the Halpe-FullBody dataset with multi-domain knowledge distillation.

Table 4: Results of ablation studies on proposed methods. Asterisks indicate the use of multi-domain knowledge distillation[2].

Table 5: Comparison of model performance on the COCO test-dev dataset[2]

Table 5: Comparison of model performance on the COCO test-dev dataset[2]

Although body-only pose estimation is not the primary objective of AlphaPose, FastPose matches the performance of state-of-the-art heatmap-based localization methods with a smaller input image and a simpler human detector.

4.5.2. Discussion

As a top-down approach, inference time for AlphaPose increases linearly with the number of individuals in the input image, but stays competitive for images with less than 20 individuals. The design of the AlphaPose framework is abstracted from specific backbone architectures, allowing significant tailoring to upstream use cases.

5. ViTPose

5.1. Approach

ViTPose uses a top-down approach, meaning it will first detect the human instances and then use ViT to estimate the keypoints of each human.

5.2. Pretraining

The ViTPose team experimented with the traditional ImageNet pretraining, which is the industry standard for pretraining but requires extra data to just the pose ones, which makes the data requirement higher for pose estimation. Hence, an alternative approach, MAE, was used on the COCO dataset for pretraining. For MAE, 75% of the patches were masked, and the model would reconstruct them. The third pretraining method tested also used MAE but using a combination of the MS COCO and AI Challenger.

With roughly only half the amount of data ImageNet has, the MAE approach using only MS COCO was able to achieve comparable results to ImageNet, with only around a 1.3 difference in AP.

5.3. Architecture

5.3.1. Transformers

Transformers are a type of neural network architecture designed to handle sequential or structured data by modeling relationships between all parts of the input. They use self-attention to allow each element to consider every other element, capturing global context efficiently. ViTPose uses plain, non-hierarchical Vision Transformers as its backbone to extract features from an individual person image, and then applies a lightweight decoder to predict the person’s pose.

5.3.2. Encoder

ViTPose first converts a image

\[X \in \mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times 3}\]into tokenized patches

\[F_0 = \text{PatchEmbed}(X) \in \mathbb{R}^{H/d \times W/d \times C}\]using a patch embedding layer, where (d) is the downsampling ratio and (C) is the channel dimension. These tokens are then processed by multiple transformer layers. At each layer (i), the features are updated as

\[F'_{i+1} = F_i + \text{MHSA}(\text{LN}(F_i)) \in \mathbb{R}^{H/d \times W/d \times C}, \quad F_{i+1} = F'_{i+1} + \text{FFN}(\text{LN}(F'_{i+1})) \in \mathbb{R}^{H/d \times W/d \times C}\]where MHSA denotes multi-head self-attention, FFN denotes the feed-forward network, and LN is layer normalization. This stack of transformer layers forms the encoder, which extracts rich features from the input image for the decoder to predict keypoints.

5.3.3. Decoder

ViTPose explores two types of lightweight decoders to generate keypoint heatmaps from the features extracted by the backbone.

The first is the classic decoder, which consists of two deconvolution blocks, each containing a deconvolution layer, batch normalization, and ReLU. These blocks upsample the feature maps by a factor of two, followed by a 1×1 convolution to produce the heatmaps. Formally,

\[K = \text{Conv}_{1\times1}(\text{Deconv}(\text{Deconv}(F_\text{out})))\]where

\[K \in \mathbb{R}^{H/4 \times W/4 \times N_k}\]and \(N_k = 17\) for the MS COCO dataset.

The second is a simpler decoder that leverages the strong representation ability of the transformer backbone. It upsamples the feature maps by four times using bilinear interpolation, applies ReLU, and then a 3×3 convolution to generate the heatmaps:

\[K = \text{Conv}_{3\times3}(\text{Bilinear}(\text{ReLU}(F_\text{out})))\]This simpler decoder, even with non-linear capacity, can achieve similar performance to the class decoder.

5.4. Performance

ViTPose models are trained using the default settings of MMPose. Input images have a resolution of 256 by 192, and the AdamW optimizer is used with an initial learning rate of 5e-4. Post-processing is performed using UDP. Models are trained for 210 epochs, with the learning rate reduced by a factor of 10 at the 170th and 200th epochs. Additionally, the layer-wise learning rate decay and stochastic drop path ratio are tuned for each model. Given these hyperparameters, even without complex architectural designs, ViTPose achieves state-of-the-art performance, reaching 80.9 AP on the MS COCO dataset.

Figure 5: Visual pose estimation results of ViTPose on some test images from COCO dataset[3]

Figure 5: Visual pose estimation results of ViTPose on some test images from COCO dataset[3]

5.5. Other Experiments and Key Findings

It was discovered that ViTPose had some other advantages over those that used CNN for feature extraction. Besides the simple structure of ViTPose, it is also scalable, flexible, and transferable.

5.5.1. Scalable

The simple architecture of ViTPose makes its model size easily adjustable by changing the number of transformer layers or feature dimensions. By fine-tuning models of different sizes, including the base, large, and huge models on the COCO dataset using the classic decoder, it was found that as the model size increased there were consistent performance improvements.

5.5.2. Flexible

As mentioned earlier, ViTPose was pretrained with various sized datasets including ImageNet, COCO, COCO and AI Challenger. The significantly smaller datasets like COCO and AI challenger were able to achieve similar results to ImageNet, showing that ViTPose is able to draw effective initialization from pre-training data of various sizes.

ViTPose is also flexible in terms of resolution. To control feature resolution, the input image size and the downsampling ratio were adjusted. For higher input resolutions, simply upsize the images and retrain. For higher feature resolutions, reduce the patch embedding stride so patches overlap without changing patch size. Both experiments showed that the performance of ViTPose increased steadily with higher input or feature resolution.

Using full self-attention on high-resolution feature maps is very memory- and computation-intensive because attention scales quadratically. To reduce this, ViTPose uses window-based attention with two enhancements: shifted windows, which allow information to flow between neighboring windows, and pooled windows, which summarize global context within each window to enable cross-window communication. These two strategies complement each other, improving performance and reducing memory usage without adding extra parameters or modules.

5.5.3. Transferable

To improve the performance of smaller models, ViTPose uses knowledge distillation, a technique for transferring knowledge from a larger, well-trained teacher model to a smaller student model. The simplest form forces the student to mimic the teacher’s output keypoint heatmaps. Additionally, ViTPose introduces token-based distillation, where a learnable “knowledge token” is trained on the teacher and then incorporated into the student’s tokens, further guiding learning. This approach helps smaller models achieve better accuracy by leveraging the representations learned by larger models.

6. Comparison

As a top-down approach, AlphaPose does not scale well as the number of individuals in the multiperson pose estimation task increases. However, it surpasses OpenPose in terms of inference speed for individual counts less than 20.

ViTPose is simpler and easier to scale than OpenPose and AlphaPose, using a vision transformer backbone with a lightweight decoder while still achieving high accuracy. It can also take advantage of pretraining and knowledge transfer to improve smaller models. However, it can use more memory and compute, be slower for real-time use, and does not yet have as many ready-to-use tools as the more established OpenPose and AlphaPose.

| OpenPose | AlphaPose | ViTPose | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epochs | N/A | 270 | 210 |

| COCO | 65.2 AP | 72.7 AP | 80.9 AP |

Table 5: Comparison of OpenPose, AlphaPose, and ViTPose mean average precision on the COCO dataset

7. Sapiens

7.1 What is Sapiens

Sapiens is one of the most recent and advanced human-pose models, introduced just last year(2024) by a Meta AI research team. Rather than being a single network, Sapiens is actually a unified collection of four complementary models designed to address core human-centric vision tasks: 2D pose estimation, body-part segmentation, depth estimation, and surface-normal prediction. In our discussion, we will focus primarily on the 2D pose-estimation component.

Trained on the extensive Humans-300M dataset,containing 300 million in-the-wild images, Sapiens demonstrates substantial improvements over the prior pose-estimation methods mentioned above. On the Humans-5k(subset of the Humans-300M) benchmark, it outperforms earlier 2D pose models by more than 7.6 mAP. This massive training dataset, far larger than datasets like ImageNet, contributes significantly to this performance boost. Sapiens mainly draws inspiration from ViTPose. However it also introduces its own architectural innovations, resulting in higher accuracy.

7.2 Approach/A Criteria to Follow

Sapiens established a set of criteria for what a human-centric vision model should achieve. The researchers defined three key requirements: generalization, broad applicability, and high fidelity. Generalization refers to the model’s ability to remain robust under new or unseen conditions. Broad applicability means the model should be adaptable across a wide range of human-centric tasks without requiring significant model changes. High fidelity ensures that the model can produce precise, high-resolution outputs. The developers trained, tested, and evaluated Sapiens against these criteria, and the resulting model successfully meets all three.

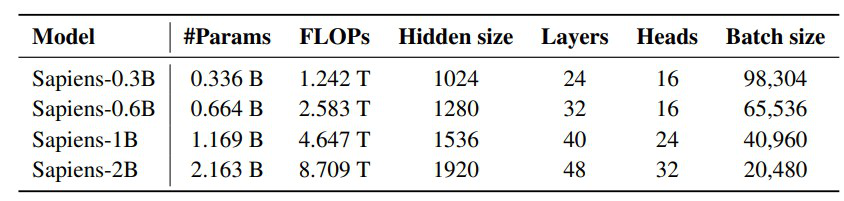

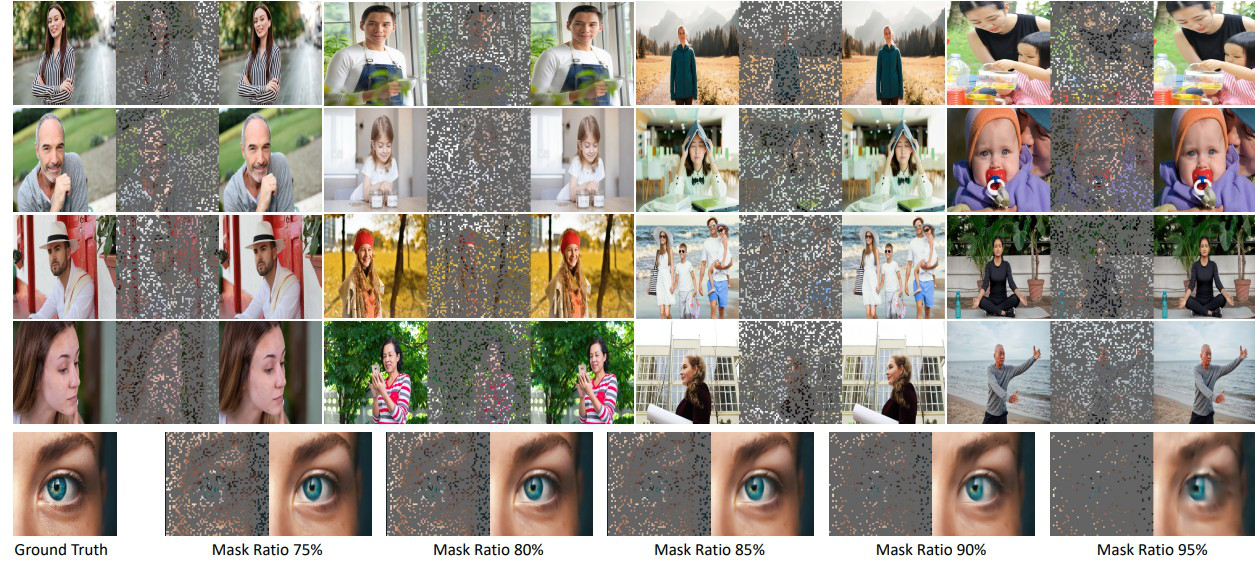

7.3 Pretraining and Architecture

A major advancement that differentiates Sapiens from some of the earlier models is its pretraining strategy. Like ViT-Pose, Sapiens adopts the MAE (masked autoencoder) pretraining approach, but it scales this idea much further. The researchers pretrained an entire family of Vision Transformer backbones, ranging from 300 million to 2 billion parameters. To achieve the high-fidelity outputs they targeted, Sapiens uses a significantly higher input resolution of 1024 pixels. 1024, as of 2024, represents nearly a 4× increase in FLOPs over the largest previously existing vision backbones.

Table 6: Sapiens encoder specifications when pretrained using the Humans-300M dataset[4]

Table 6: Sapiens encoder specifications when pretrained using the Humans-300M dataset[4]

Sapiens employs an encoder–decoder architecture, allowing the model to reconstruct masked images with impressive accuracy during pretraining. The encoder is initialized with weights during pertaining and it maps the visible images to a latent representation. The decoder is initialized randomly and it reconstructs the initial image using the latent representation given to it. Similar to the ViT approach the model divides the image input into different patches and randomly masks these patches. This strong reconstruction capability helps the model learn richer human-centric features, ultimately improving downstream pose-estimation performance.

Figure 6: MAE reconstruction given different mask percentages[4]

7.4 How did Sapiens improve prior models (KeyPoints)

During finetuning, Sapiens uses an encoder–decoder architecture and follows a top-down pose-estimation approach. For optimization, Sapiens uses the AdamW optimizer, applying cosine annealing during pretraining and linear learning-rate decay during finetuning.

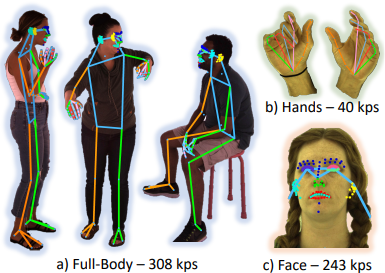

Data quality plays a critical role in model performance, and Sapiens was trained using the extensive Humans-300M dataset. While this is an improvement in data size and resolution to some prior models like ImgNet, ground truth label quality is equally important. Currently 2D pose estimation uses keypoints as a main label to figure out pose,.To improve pose-estimation accuracy, the team introduced a much denser set of 2D whole-body keypoints for human-pose recognition. Their enhanced annotation scheme for keypoints, covered detailed regions such as the hands, feet, face, and full body. These richer, more precise labels enable Sapiens to learn fine-grained human structure and deliver significantly better pose-estimation performance.

Similar to ViTPose, Sapiens incorporates a Pose Estimation Transformer (P), which detects keypoints using bounding-box inputs and heatmap prediction. In the top-down framework, the model aims to predict the locations of K keypoints in an input image, where K is a tunable hyperparameter that directly affects accuracy. The team experimented with these encoder–decoder variants for pose classification using K = 17, 133, and 308 keypoints. While ViTPose operated with at most 133 keypoints, Sapiens significantly expanded this value to 308 for whole-body skeletons. For face-pose tasks, previous models typically used 68 facial keypoints, but Sapiens found through hyperparameter testing that 243 facial keypoints yielded the best results. Achieving this required new annotations at these higher densities, and these richer labels ultimately drove the model’s substantial accuracy gains.

Figure 7: Example ground truth annotations with the new keypoint parameters[4]

7.5 Performance

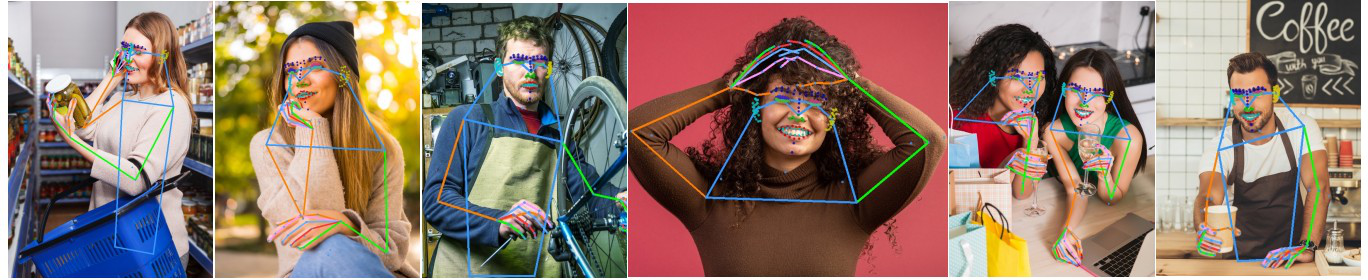

Figure 8. Pose estimation with Sapiens-1B for 308 keypoints images[4]

Figure 8. Pose estimation with Sapiens-1B for 308 keypoints images[4]

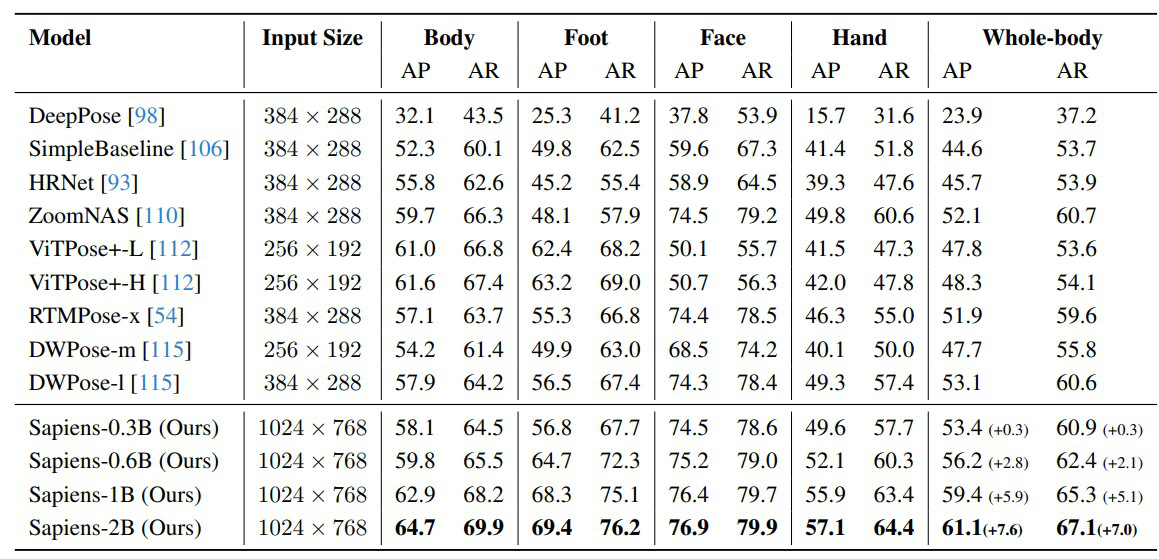

For the 2D pose-estimation task, the team trained on 1 million images from the 3M dataset and evaluated performance on a 5,000-image test set. Because earlier models did not support Sapiens’ full set of 308 keypoints, the researchers evaluated accuracy using both the 114 keypoints that overlap with their 308-keypoint scheme and the standard 133-keypoint vocabulary from the COCO-WholeBody dataset(used as a tester in our prior models as well).

The results show substantial improvements. Compared to ViTPose, which also uses MAE pretraining and an encoder–decoder architecture, Sapiens achieves significantly higher accuracy due to its higher-resolution inputs, larger and denser keypoint annotations, and broader training data. Specifically, Sapiens reports +5.6 P and +7.9 AP gains over the strongest prior ViTPose variants.

Table 7: Results of Sapiens on Humans-5K test set compared to some other models[4]

Table 7: Results of Sapiens on Humans-5K test set compared to some other models[4]

8. Conclusion

A brief survey of representative approaches to human pose estimation in the past seven years has revealed significant strides in terms of model accuracy, speed, and capabilities. The evolution is marked by a clear trend away from the complex, bottom up approach of OpenPose, which relied on hand crafted features like Part Affinity Fields, towards efficient, simple, and scalable top down transformer architectures. Recent state of the art models, exemplified by AlphaPose, ViTPose and the foundation model Sapiens which improved the amount of keypoints used, achieve peak performance through architectural simplification, high resolution inputs, and aggressive data scaling on massive, high fidelity datasets.

While 2D pose estimation is becoming a highly refined task, its fundamental limitation remains the depth ambiguity that multiple 3D poses can project to the same 2D image. Therefore, the future of HPE is moving rapidly into 3D human pose estimation and Human Mesh Recovery (HMR) to reconstruct the full 3D body shape and pose. Current research also heavily focuses on generative models (like diffusion models and GANs) to predict plausible future poses or generate more realistic and diverse 3D human motion sequences. These advancements are critical for applications in robotics, virtual reality, and healthcare, where a true understanding of spatial human movement is essential.

9. References

[1] Z. Cao, G. Hidalgo, T. Simon, S. Wei, Y. Sheikh, “OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1812.08008, 2019.

[2] H. Fang, J. Li, H. Tang, C. Xu, H. Zhu, Y. Xiu, Y. Li, C. Lu, “AlphaPose: Whole-Body Regional Multi-Person Pose Estimation and Tracking in Real-Time,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2211.03375, 2022.

[3] Y. Xu, J. Zhang, Q. Zhang, D. Tao, “ViTPose: Simple Vision Transformer Baselines for Human Pose Estimation,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2204.12484, 2022.

[4] R. Khirodkar, T. Bagautdinov, J. Martinez, S. Zhaoen, A. James, P. Selednik, S. Anderson, S. Saito, “Sapiens: Foundation for Human Vision Models,” https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.12569, 2024.

[5] “Human pose estimation: Importance, types, challenges and use cases,” https://www.softwebsolutions.com/resources/human-pose-estimation/, 2025.