Food Detection

Food detection is a subset of image classification that is able to classify specific foods. As such, it requires the ability to learn finer-grain details to differentiate specific foods. In this paper, we investigate how three models, DeepFood, WISeR, and Noisy-ViT, built upon state-of-the-art (at the time) object classification models for food detection, along with a dataset built for food detection Food-101. On this dataset, DeepFood performed at a 77.40% accuracy, WISeR performed at a 90.27% accuracy, and Noisy-ViT performed at a 99.50% accuracy.

- Introduction

- Food Detection vs. Object Detection

- Food-101

- DeepFood

- WISeR Residual Network

- NoisyViT

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Reference

Introduction

Food detection is the task of seeing an image and determining what specific food is in the image. These classifications can be used in a variety of different applications such as monitoring diet and nutrient intake, assessing food quality, and sorting foods in large scale factories. Diet monitoring can be critical to improve the health of many by creating an easy way to keep track of the exact foods and nutritional content a person is consuming. Assessing food quality can assist farmers with detecting ripe produce and when to harvest, and also assist quality assurance in food factories by speeding up the process. Also in factories, labeling foods makes sorting foods a much easier and faster task. With the rise in computer vision in recent years, classifications can be made using machine learning techniques by inputting the image of the food into a model that outputs what type of food it is with varying levels of precision. In this report, we will investigate what makes the food detection task unique from a more general object detection and what innovations have been made to improve the performance of food detection models.

Food Detection vs. Object Detection

Food detection is a form of object detection, which exists as its own general task. Object detection seeks to determine what a specific object is in an image. The list of objects that can potentially be outputted are very broad across vastly different genres, as it is designed to work as a generalized task. While this is ideal for a more general use case, it does not distinguish finer grain details within individual genres of image categories [1]. For instance, classifying an object as a car compared to classifying an object as a Honda Accord. Images of food do not have significant spacial relationships such as the form and structure of body parts for a human being or subject and background images for outdoor images. Because of this, models for food detection have to capable of computing finer grain details to make its decisions.

Food-101

To train and test models on food detection, Bossard et al. [1] created the Food-101 dataset. Standard object detection datasets such as ImageNet have a vast range of different genres of images in different scenes. Food detection requires just images of food to be able to learn finer grain details of each food. This dataset consists of 101000 images. These images are split into 101 categories of the 101 most popular foods and 1000 randomly picked images for each. Additionally, in those 1000 images, 750 are picked as training data and 250 as test data, and each image is 512 pixels by 512 pixels. In this paper, we will focus on the following models’ performance only on the Food-101 dataset.

Fig 1. 100 samples of 100 of the categories of Food-101 [1].

DeepFood

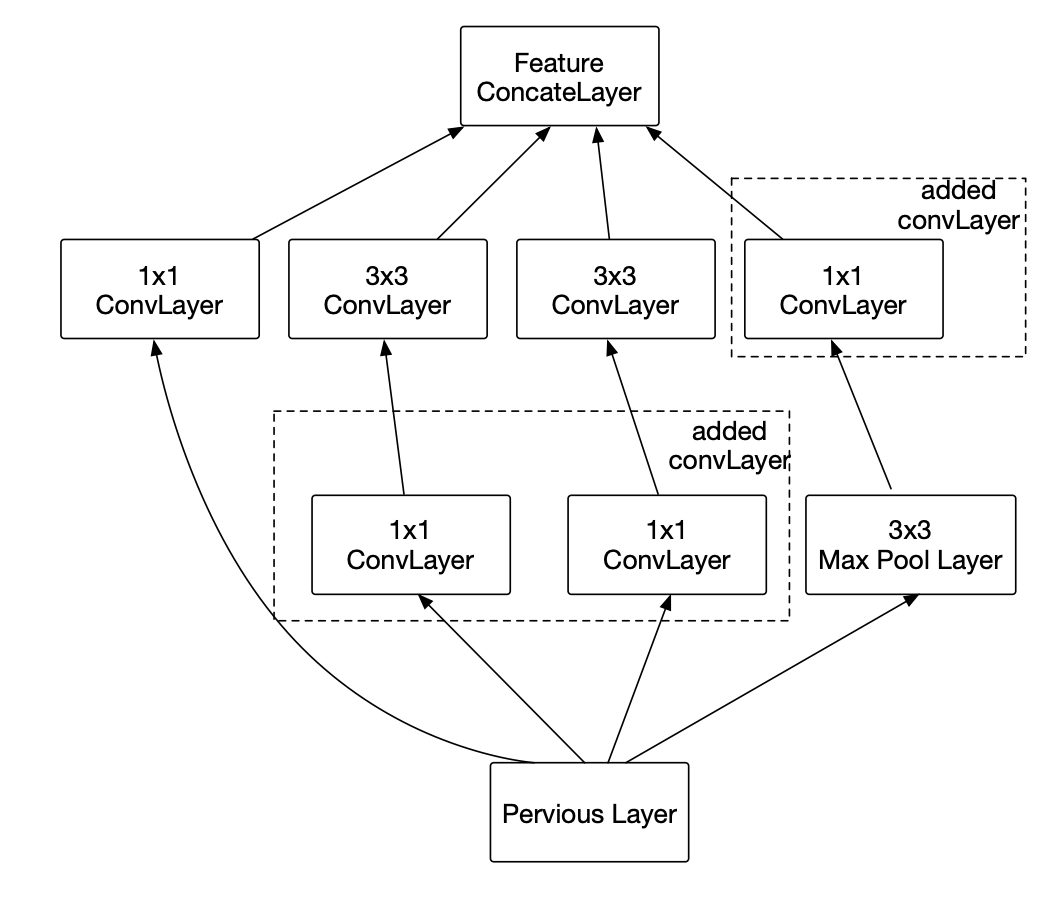

Proposed by Liu et al. [2], The DeepFood model utilized a fine-tuned GoogleNet model on food detection datasets. The GoogleNet model innovated upon then-current day CNNs by introducing the Inception Module.

Fig 2. Diagram of an inception module [2].

The inception module allows for increased computational power while decreasing computation complexity, allowing for quicker training and inference. These inception modules are then concatenated together into a 22 layer CNN. The model discussed in this paper took a pre-trained GoogleNet model and then they fine- tuned the model on the Food-101 dataset and another food detection dataset called UEC-256.

WISeR Residual Network

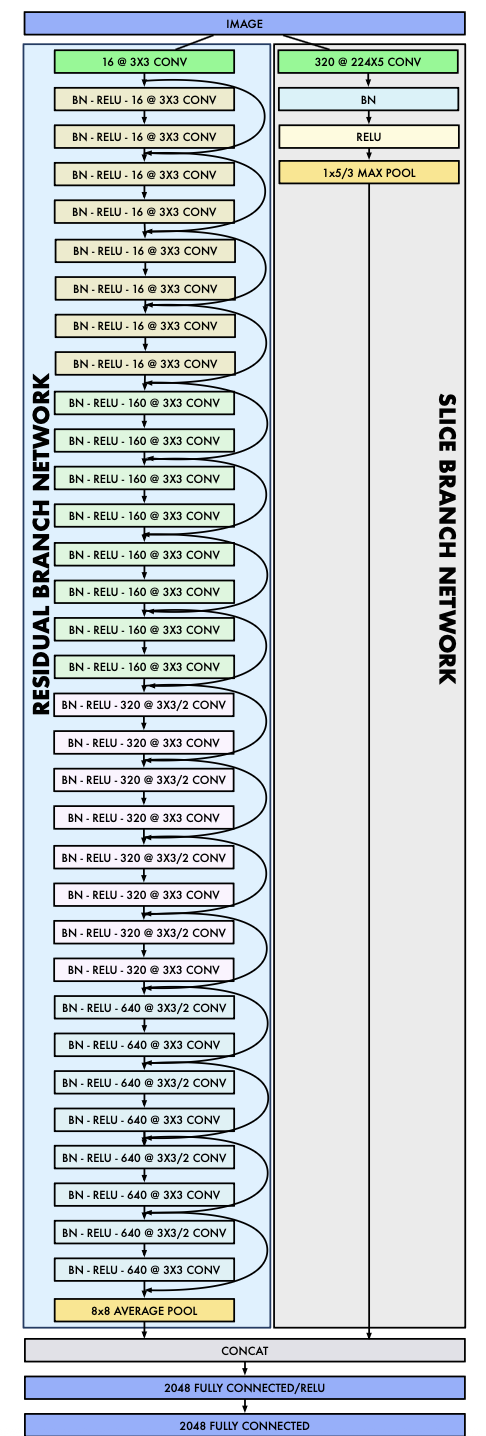

Proposed by Martinel et al. [3], The Wide-Slice Residual Network is a Convolutional Nerual Network that applies the residual learning on top of a new introduced convolutional layer used to locate finer grain details for the food detection task. This model was pre-trained on ImageNet and then fine-tuned with the Food-101 dataset and also UEC-256 and UEC-1000.

Fig 3. Diagram of the WISeR architecture [3].

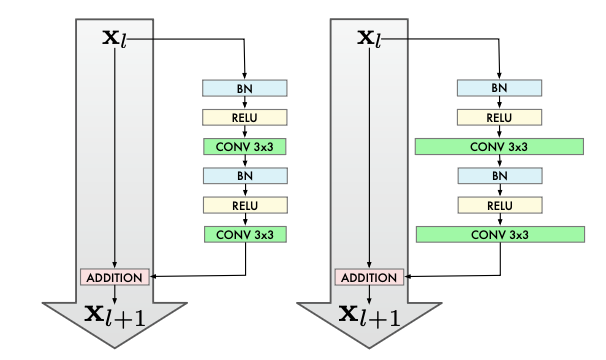

Wide Residual Block

Residual learning through a block of convolution layers is defined as followed: \(x + F(x) = \text{output}\). This innovation allowed for the blocks to learn the identity function without the burden of trying to recreate the input, allowing for much deeper networks without degradation of quality. The innovation here is widening the convolution layers by increasing the amount of kernels to increase the size of the feature map.

Fig 4. Diagram of the standard residual block (left) and the widened convolution layers of the WISeR archiecture (right) [3].

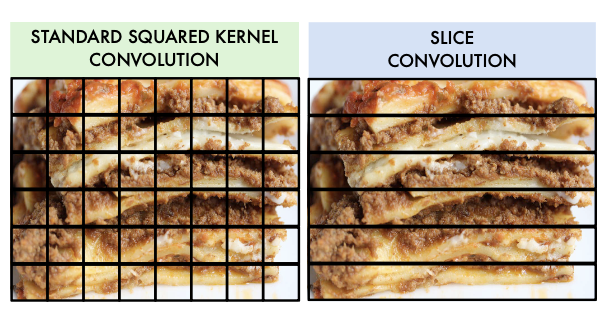

Slice Convolution

The standard convolution layer breaks up the image into kernels and transfers that information into a feature map. Kernels are traditionally defined as squares and is what convolutional layers use to learn spatial information and features. In this model as seen on Figure 2, in addition to using many of these convolution layers, there exists a branch that uses a slice convolution layer that breaks up kernels into horizontal slices to learn features on vertical layers. The intuition is there are many foods that are stacked veritcally such as burgers and sandwiches.

Fig 5. Comparing standard square kernels to slice convolution for lasagna [3].

NoisyViT

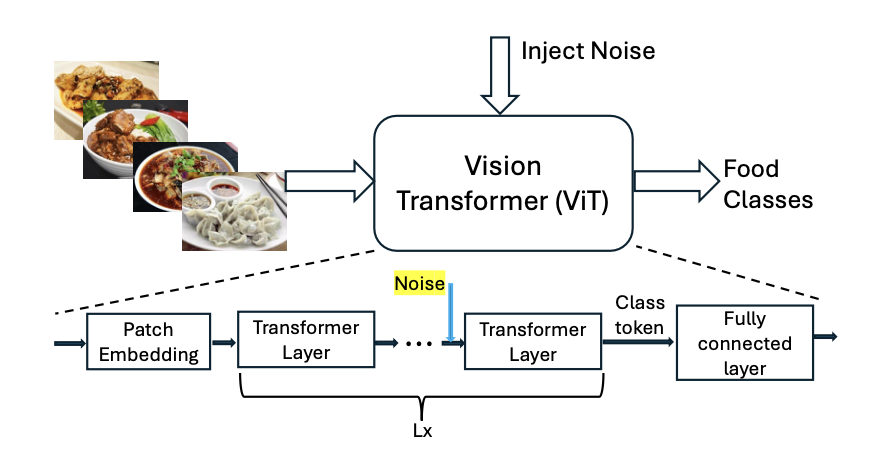

Proposed by Ghosh and Sazonov [4], this model built upon the Visual Transformer to tailor its use case to handle food detection. The Visual Transformer introduces self-attention to computer vision models which allows the model to learn with respect to context across the data. NoisyViT builds upon the standard ViT by injecting noise randomly in between transformer layers during training. During testing, the noise injection was removed. The noise was injected as a linear transformation of a feature space and was injected to a random layer. This model was built on top of a Visual Transformer Model pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset, and then fine-tuned with Food-101, Food-2k and CNFOOD-241 datasets.

Fig 6. Diagram of the noise injection in the NoisyViT architecture [4].

Results

Compared to other off-the-shelf models, this is how each model performed on the Food-101 dataset.

| Top 1 Performance (%) | Top 5 Performance (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | 56.40 | N/A |

| DeepFood [2] | 77.40 | 93.70 |

| ResNet-200 | 88.38 | 97.85 |

| WISeR [3] | 90.27 | 98.71 |

| ViT-B | 88.46 | 98.05 |

| Noisy-ViT-B [4] | 99.50 | 100.00 |

Discussion

As we can see from the results, the Noisy Visual Transformer performs almost perfectly on the Food-101 dataset, and the others make improvements over more general image classification models. The improvements against the other food detection models improve over time similar to the trajectory of how the general image classificaiton models, for example GoogleNet outperforming AlexNet, and then ResNet outperforming any other CNN based architecture. Injecting noise into the Visual Transfomrer improved performance drastically compared to every other model showcased. Comparing ResNet to WISeR, we can see that the slice convolution and wider convolution layers improve performance and we can guess that these innovations allow for the model to find the finer grain details in food detection.

Conclusion

Food detection is a growing problem that has high upside in its applications. From diet monitoring for individuals to potentially combat obesity and diabetes to applications in food factories, food detection is the central task required. With the introduction of object classification models, we can use these innovations for food detection, but they require additional modifications to learn the finer-grain details of food images. We found that the DeepFood model performs at a 77.40% accuracy, WISeR performs at a 90.27% accuracy, and the Noisy Visual Transformer performs incredibly well at a 99.50% accuracy on the Food-101 dataset. Each of these models showcase the increasing effectiveness of computer vision models on the food detection task.

Reference

[1] L. Bossard, M. Guillaumin, and L. Van Gool, “Food-101 – Mining Discriminative Components with Random Forests,” in Computer Vision – ECCV 2014, D. Fleet, T. Pajdla, B. Schiele, and T. Tuytelaars, Eds., Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2014, pp. 446–461. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-10599-4_29.

[2] C. Liu, Y. Cao, Y. Luo, G. Chen, V. Vokkarane, and Y. Ma. Deepfood: Deep learning-based food image recognition for computer-aided dietary assessment. In IEEE International Conference on Smart Homes and Health Telematics, volume 9677, pages 37–48, 2016.

[3] Martinel, Niki, Gian Luca Foresti, and Christian Micheloni. “Wide-slice residual networks for food recognition.” 2018 IEEE Winter conference on applications of computer vision (WACV). IEEE, 2018.

[4] T. Ghosh, and E. Sazonov. “Improving Food Image Recognition with Noisy Vision Transformer.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.18997 (2025).