From Classifiers to Assistants: The Evolution of Visual Question Answering

Visual Question Answering (VQA) represents a fundamental challenge in artificial intelligence: the ability to understand both visual content and natural language, then reason across these modalities to produce meaningful answers. This report traces the evolution of VQA from its formal definition as a classification task in 2015, through the era of sophisticated attention mechanisms, to its modern integration into Large Multimodal Models. We analyze three papers that define this trajectory, revealing how VQA transformed from a specialized benchmark into a core capability of general-purpose AI assistants.

- Introduction

- 1. The Foundation: Defining VQA as a Task

- 2. The Architectural Shift: Attention Over Objects

- 3. The Paradigm Shift: VQA as a Capability of LLMs

- 4. Analysis: The Evolution of VQA

- 5. Conclusion

- References

Introduction

Computer Vision has historically been defined by narrow, well-specified tasks. Image classification asks: Is there a cat in this image? Object detection asks: Where is the cat? Semantic segmentation asks: Which pixels belong to the cat? While each task pushed the field forward, they shared the fundamental limitation that the question was always predetermined by the researcher, not posed by a user.

Visual Question Answering (VQA) broke this paradigm. By allowing any natural language question about any image, VQA became what some researchers called the “Visual Turing Test”, a task that, if solved perfectly, would require human-level understanding of both vision and language.

In this survey, we analyze three papers that chart the evolution of VQA:

| Paper | Year | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| VQA: Visual Question Answering [1] | 2015 | Formalized the task and introduced the benchmark |

| Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention [2] | 2018 | Object-level attention via Faster R-CNN |

| Visual Instruction Tuning (LLaVA) [3] | 2023 | Merged VQA into Large Language Models |

These papers represent three distinct eras: problem definition, architectural optimization, and paradigm shift. Together, they tell the story of how a classification task became a conversation.

1. The Foundation: Defining VQA as a Task

Paper: VQA: Visual Question Answering - Antol et al., ICCV 2015 [arxiv]

Before 2015, the intersection of vision and language was largely limited to image captioning, which is generating a single description for an image. While valuable, captioning provides no mechanism for targeted queries. A user cannot ask “What color is the hat?” and expect a relevant response from a captioning model.

Antol et al. formalized Visual Question Answering as a distinct task: given an image \(I\) and a free-form natural language question \(Q\), the system must produce an answer \(A\).

1.1 The VQA Dataset

The authors introduced VQA v1.0, one of the largest vision-language datasets of its time:

| Statistic | Count |

|---|---|

| Images (COCO + Abstract Scenes) | ~254,000 |

| Questions | ~764,000 |

| Answers (crowdsourced) | ~10,000,000 |

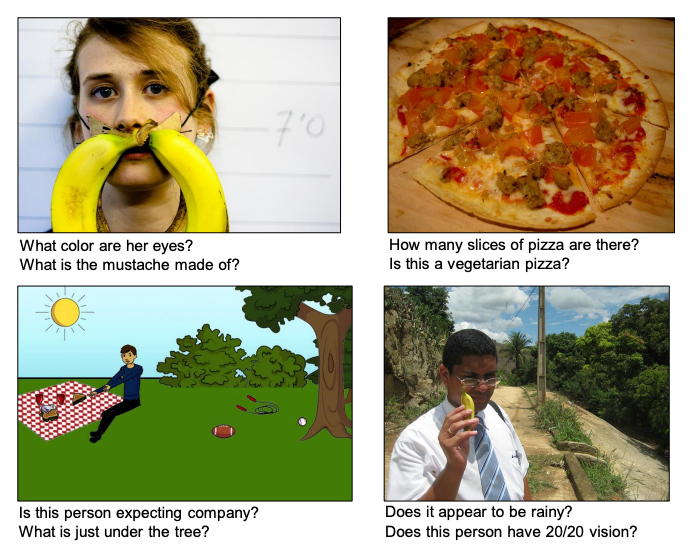

The dataset included both real photographs from MS-COCO and synthetic abstract scenes. This dual setup allowed researchers to isolate reasoning capabilities from visual recognition challenges.

Questions spanned multiple categories:

- Object Recognition: “What is the man holding?”

- Counting: “How many birds are in the image?”

- Spatial Reasoning: “Is the cat on the left or right of the dog?”

- Common Sense: “Why is the person wearing a helmet?”

- Yes/No: “Is it raining?”

Fig 1. Typical VQA input/output examples [1].

1.2 Formulation as Classification

A critical design decision was to treat VQA as a multi-class classification problem. Rather than generating free-form text, models select from a fixed vocabulary of the most frequent answers (typically the top 1000).

This simplification made training tractable with 2015-era techniques but introduced a fundamental constraint: the model could never produce an answer outside its vocabulary, even if the correct answer was obvious.

1.3 The Baseline Architecture

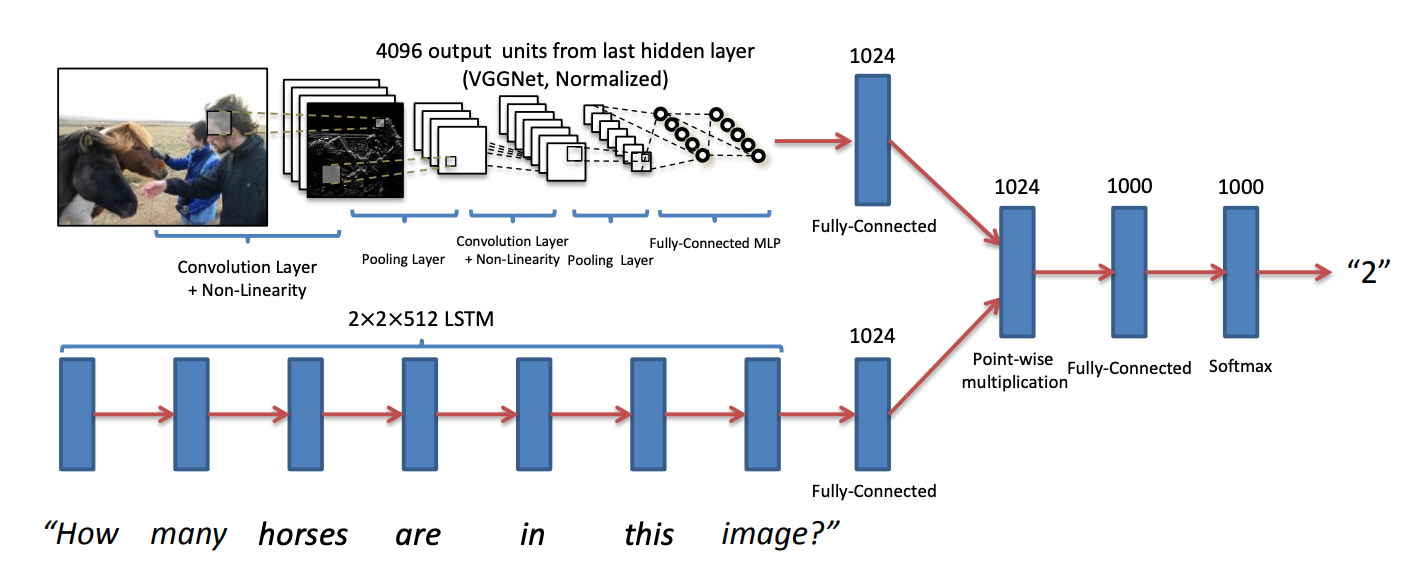

The paper proposed a two-channel “fusion” architecture:

Image Channel: A VGGNet (pre-trained on ImageNet) processes the image and outputs a 4096-dimensional feature vector from the final fully-connected layer.

Question Channel: An LSTM reads the question word-by-word, producing a fixed-length encoding from its final hidden state.

Fusion: The image and question vectors are combined via element-wise multiplication:

\[h = \text{tanh}(W_I \cdot v_I) \odot \text{tanh}(W_Q \cdot v_Q)\]Output: A softmax classifier over the answer vocabulary produces the final prediction.

Fig 2. Their best performing VQA model (LSTM + VGGNet) [2].

1.4 Evaluation Metric

The authors introduced an evaluation metric that accounts for answer variability:

\[\text{Accuracy} = \min\left(\frac{n}{3}, 1\right)\]where \(n\) is the number of annotators (out of 10) who provided that answer.

An answer receives full credit if at least 3 out of 10 annotators provided it, partial credit otherwise. This soft metric acknowledges that questions like “What color is the sky?” might legitimately have answers like “blue”, “light blue”, or “azure”.

1.5 The Problem of Language Bias

The authors discovered that models could exploit language priors to achieve surprisingly high accuracy without truly understanding images. By analyzing the dataset, they found strong correlations between question patterns and answers. For example, questions beginning with “How many…” were frequently answered with small numbers, regardless of the image content.

This revealed a fundamental challenge: models could achieve respectable scores while barely “looking” at images. This problem would motivate later work on VQA v2.0, which was designed to reduce such language biases by balancing the answer distribution.

2. The Architectural Shift: Attention Over Objects

Paper: Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention for Image Captioning and Visual Question Answering - Anderson et al., CVPR 2018 [arxiv]

By 2017, attention mechanisms had become standard in VQA. Models would compute attention weights over a spatial grid of CNN features (e.g., a \(14 \times 14\) grid from ResNet), allowing the model to “focus” on relevant regions for each question.

However, Anderson et al. identified a fundamental limitation: grids are unnatural. When a human answers “What is the man holding?”, they don’t scan a uniform grid, but instead they focus on semantically meaningful objects. A grid cell might contain half of a tennis racket and part of the sky, mixing useful and irrelevant information.

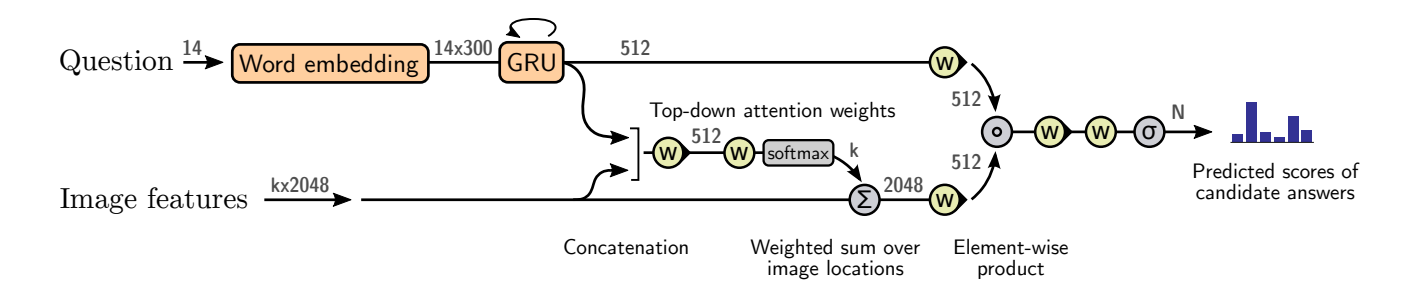

2.1 Bottom-Up Attention: Object Proposals

The key innovation was to replace grid-based features with object-level features extracted by a Faster R-CNN detector pre-trained on Visual Genome.

Bottom-Up Process:

- Faster R-CNN proposes bounding boxes for salient objects/regions

- For each box, extract a feature vector \(v_i \in \mathbb{R}^{2048}\) from the pooled ROI

- Keep the top \(k\) proposals (found \(k = 36\) works well)

The result is a set of features \(V = \{v_1, v_2, ..., v_k\}\) where each \(v_i\) corresponds to a semantically meaningful region (a person, a hat, a tennis racket) rather than an arbitrary grid cell.

2.2 Top-Down Attention: Question-Guided Weighting

Once objects are detected, the model must determine which objects are relevant to the question. This is the top-down component of task-conditioned attention.

Given the question encoding \(q\), attention weights are computed:

\[a_i = w_a^T \cdot \text{tanh}(W_v v_i + W_q q)\] \[\alpha_i = \text{softmax}(a_i)\]The final visual representation is a weighted sum:

\[\widehat{v} = \sum_{i=1}^{k} \alpha_i v_i\]This \(\widehat{v}\) is then combined with the question encoding to produce the answer.

2.3 The Complete Architecture

Fig 3. Bottom-up regions (from a detector) combined with top-down, question-guided attention for VQA [2].

The fusion mechanism used in this work was based on element-wise multiplication with a gating mechanism, but the object-level attention was compatible with various fusion strategies.

2.4 Results and Impact

On the VQA v2.0 validation set, the Up-Down model significantly outperformed ResNet baselines across all question types:

| Model | Yes/No | Number | Other | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet (7×7) | 77.6 | 37.7 | 51.5 | 59.4 |

| Up-Down | 80.3 | 42.8 | 55.8 | 63.2 |

On the official VQA v2.0 test-standard server, an ensemble of 30 Up-Down models achieved first place in the 2017 VQA Challenge:

| Model | Yes/No | Number | Other | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Up-Down (Ensemble) | 86.60 | 48.64 | 61.15 | 70.34 |

This paper had significant impact on the field. The authors released pre-extracted object features publicly, which many subsequent VQA systems adopted as a standard visual representation.

2.5 Qualitative Analysis

The attention weights provided interpretability. For the question “What sport is being played?”, the model would attend strongly to:

- The player’s uniform

- The ball

- The sports equipment

This provided evidence that the model was “reasoning” about relevant objects rather than exploiting spurious correlations.

2.6 Limitations of the Pre-Transformer Era

Despite its success, bottom-up attention had inherent constraints:

-

Fixed Object Vocabulary: The Faster R-CNN was trained on Visual Genome’s 1,600 object classes. Objects outside this vocabulary were poorly represented.

-

Two-Stage Pipeline: The object detector was frozen during VQA training, preventing end-to-end optimization.

-

Limited Reasoning: While attention helped localization, complex reasoning (e.g., “If the left traffic light turns red, should the car stop?”) remained challenging.

3. The Paradigm Shift: VQA as a Capability of LLMs

Paper: Visual Instruction Tuning - Liu et al., NeurIPS 2023 [arxiv]

The emergence of Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-3 and LLaMA fundamentally changed the landscape of AI. These models demonstrated remarkable reasoning capabilities through pure text, but they were blind to images.

Liu et al. introduced LLaVA (Large Language-and-Vision Assistant), demonstrating that connecting a vision encoder to an LLM creates a powerful multimodal system where VQA is just one of many emergent capabilities.

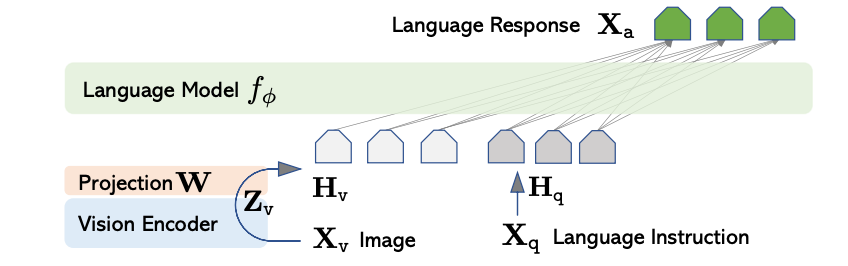

3.1 Architecture: Connecting Vision to Language

LLaVA’s architecture is elegantly simple:

Vision Encoder (CLIP ViT-L/14): A frozen CLIP visual encoder processes the image into a sequence of visual tokens:

\[Z_v = \text{ViT}(I) \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times D_v}\]where \(N\) is the number of image patches and \(D_v\) is the visual feature dimension.

Projection Layer: A trainable linear projection maps visual features to the LLM’s embedding space:

\[H_v = W \cdot Z_v, \quad W \in \mathbb{R}^{D_l \times D_v}\]where \(D_l\) is the LLM’s hidden dimension.

Language Model (Vicuna/LLaMA): The projected visual tokens \(H_v\) are concatenated with text token embeddings and fed to the LLM:

\[P(X_a \mid H_v, X_q) = \prod_{i=1}^{L} P(x_i \mid H_v, X_q, X_{a,<i})\]where \(X_q\) is the question and \(X_a\) is the generated answer.

Fig 4. LLaVA-style setup: vision encoder → projector → LLM decoder that generates the answer [3].

3.2 Visual Instruction Tuning: The Data Innovation

The architectural contribution was matched by a data innovation. Rather than collecting standard VQA pairs, the authors used GPT-4 to generate instruction-following data from image captions and bounding boxes.

Three types of data were generated:

1. Conversation:

User: What do you see in this image?

Assistant: I see a busy city street with people walking and cars...

User: What's the weather like?

Assistant: Based on the shadows and bright lighting, it appears to be

a sunny day...

2. Detailed Description:

User: Describe this image in detail.

Assistant: This image shows a cozy kitchen with wooden cabinets, a

marble countertop, and stainless steel appliances. On the

counter, there are fresh vegetables including tomatoes and

cucumbers, suggesting someone is preparing a meal...

3. Complex Reasoning:

User: What might happen next in this scene?

Assistant: Given that the traffic light is yellow and the pedestrian

is in the crosswalk, the cars will likely stop soon, and

the pedestrian will finish crossing before the light changes...

This instruction-following format taught the model to generate helpful, detailed, conversational responses rather than just single-word answers.

3.3 Training Procedure

LLaVA uses a two-stage training process:

Stage 1: Pre-training (Feature Alignment)

- Freeze: Vision encoder + LLM

- Train: Projection layer \(W\)

- Data: 595K image-text pairs (filtered from CC3M)

- Objective: Next-token prediction

Stage 2: Fine-tuning (End-to-End)

- Freeze: Vision encoder

- Train: Projection layer \(W\) + LLM

- Data: 158K visual instruction-following samples

- Objective: Next-token prediction on assistant responses

3.4 Comparison: Classification vs. Generation

The shift from classification to generation fundamentally changed what VQA models could do:

| Aspect | Classification (2015-2020) | Generation (2023+) |

|---|---|---|

| Answer format | Single word/phrase | Free-form text |

| Answer vocabulary | Fixed (1000-3000) | Unlimited |

| Reasoning | Implicit | Explicit (can explain) |

| Multi-turn | No | Yes (conversation) |

| Training signal | Cross-entropy on labels | Next-token prediction |

3.5 Results

On the Science QA multimodal benchmark, LLaVA achieved strong performance compared to prior methods:

| Method | Average |

|---|---|

| Human | 88.40 |

| LLaVA | 90.92 |

| LLaVA + GPT-4 (judge) | 92.53 |

LLaVA achieved 90.92% accuracy, outperforming humans (88.40%). When combined with GPT-4 as a judge, performance increased to 92.53%, setting a new state-of-the-art on this benchmark.

4. Analysis: The Evolution of VQA

4.1 Architectural Evolution

| Era | Visual Representation | Language Model | Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Global CNN features | LSTM | Element-wise product |

| 2018 | Object proposals (R-CNN) | GRU/LSTM | Bilinear attention |

| 2023 | CLIP patch embeddings | LLM (7B-70B params) | Projection + concatenation |

4.2 What Changed and What Didn’t

Changed:

- Model scale: From millions to billions of parameters

- Training data: From curated VQA pairs to web-scale + synthetic

- Output: From classification to generation

- Evaluation: From accuracy to human preference

Didn’t Change:

- The core challenge: grounding language in visual content

- The need for reasoning beyond pattern matching

- Sensitivity to language priors (now called “hallucinations”)

4.3 The Attention Trajectory

Attention mechanisms evolved significantly:

- 2015: No explicit attention (used global image features)

- 2017: Spatial attention over CNN grids

- 2018: Object-level attention via detection

- 2023: Self-attention within Transformers (implicit in ViT and LLM)

Modern LLMs perform attention internally as the question tokens attend to visual tokens through the Transformer’s multi-head attention. This is more flexible than explicit attention layers but less interpretable.

5. Conclusion

The evolution of Visual Question Answering tells a broader story about AI research:

-

Define the problem: The 2015 VQA paper introduced an entirely new evaluation paradigm for multimodal AI. By creating a large-scale dataset and standardized metrics, it enabled the research community to systematically measure progress on vision-language understanding.

-

Optimize within the paradigm: Bottom-up attention showed that better visual grounding (objects vs. grids) improved performance within the classification framework.

-

Shift the paradigm: Visual instruction tuning demonstrated that VQA could become a natural capability of general-purpose language models, removing the need for task-specific architectures.

Today, VQA is no longer a standalone task but a capability of multimodal assistants like GPT, Gemini, and Claude. The best VQA “models” are simply vision-language models prompted to answer questions.

This trajectory suggests that future progress will come not from VQA-specific innovations but from advances in:

- Visual representation learning (better vision encoders)

- Language model scaling and alignment (larger, safer LLMs)

- Multimodal training data (more diverse, higher quality)

The question for researchers is no longer “How do we build a VQA model?” but rather “How do we build AI systems that truly understand the visual world?” VQA was a extremely valuable stepping stone on this longer journey and continues to be a crucial part of the way we measure the ability of vision-language models. More VQA benchmarks are being created all the time, with specific focuses on a wide variety of tasks and subjects that align with people’s needs.

References

[1] Antol, S., Agrawal, A., Lu, J., Mitchell, M., Batra, D., Zitnick, C.L., & Parikh, D. (2015). VQA: Visual Question Answering. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV).

[2] Anderson, P., He, X., Buehler, C., Teney, D., Johnson, M., Gould, S., & Zhang, L. (2018). Bottom-Up and Top-Down Attention for Image Captioning and Visual Question Answering. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

[3] Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q., & Lee, Y.J. (2023). Visual Instruction Tuning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS).