Streetview Semantic Segmentation

[Project Track: Project 8]Semantic segmentation models achieve high overall accuracy on urban datasets, yet systematically fail on thin structures and object boundaries critical for safety-relevant perception. This project presents a diagnostic-driven framework for understanding segmentation failures on Cityscapes and introduces a SAM3-guided boundary supervision method that injects geometric priors into SegFormer. By combining cross-model difficulty analysis with geometry-aware auxiliary training, we demonstrate targeted improvements on thin and boundary-sensitive classes without increasing inference cost.

- Diagnosing and Improving Boundary Failures in Urban Semantic Segmentation via SAM3-Guided Supervision

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Background and Related Work

- 3. Cross-Model Difficulty Analysis Framework

- 4. Improving the Baseline: OHEM and Oversampling

- 5. Method Overview: Geometry-Aware Supervision

- 6. Model Architecture

- 7. Implementation Details

- 8. Experimental Setup

- 9. Results

- 10. Analysis and Observations

- 11. Limitations

- 12. Conclusion

- 13. Future Work

- References

Diagnosing and Improving Boundary Failures in Urban Semantic Segmentation via SAM3-Guided Supervision

1. Introduction

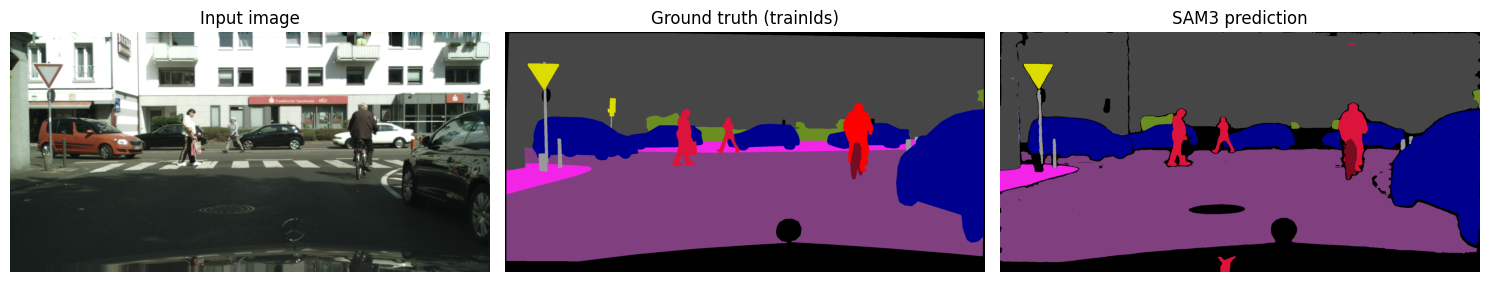

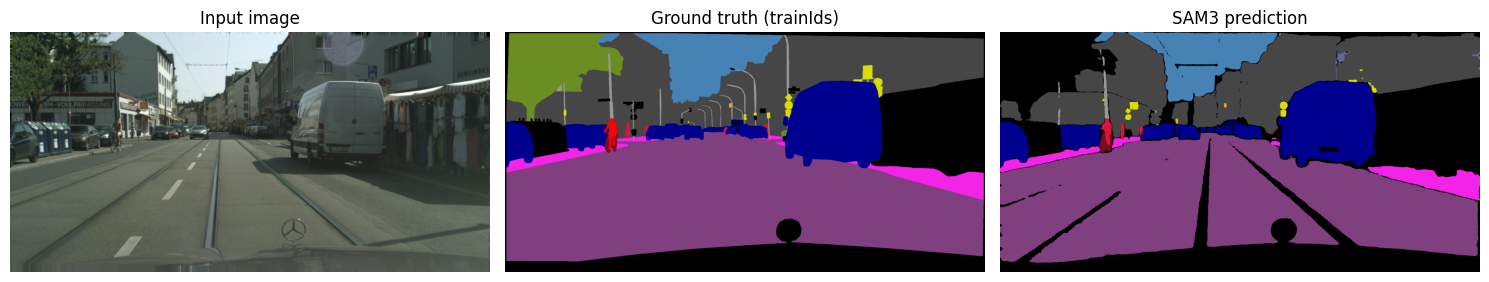

Fig 1. SAM3 output and example of the semantic segmentation problem in urban scenes.

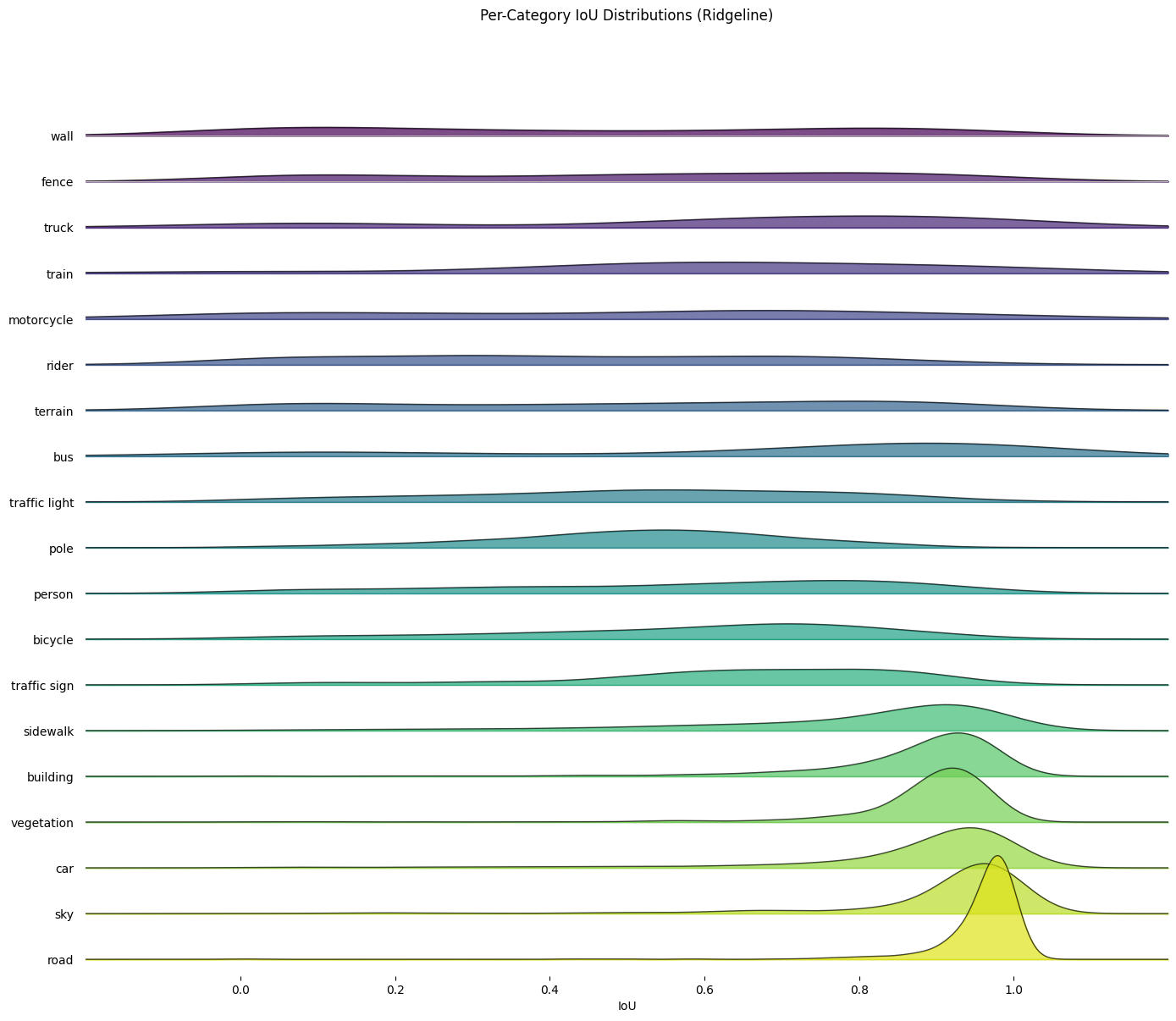

Semantic segmentation of urban street scenes (Example shown in Figure 1) is a foundational task for autonomous driving, robotics, and urban mapping. Modern deep learning models—particularly transformer-based architectures—achieve strong performance on large, visually dominant classes such as roads, buildings, and sky. However, despite high mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU), these models exhibit consistent failure modes when segmenting thin structures (e.g., poles, traffic signs, bicycle frames) and complex object boundaries. This can be seen clearly in Figure 2, which highlights the performance disparity between the large, dominant classes with sharp peaks near perfect IoU, indicating consistent reliability. In contrast, the thin categories show broad, flattened distributions, visually confirming the high variance and frequent failure modes associated with segmenting thin geometry.

Fig 2. Per-Category IoU distributions (Ridgeline Plot) for the SegFormer baseline.

These failure modes are problematic for two reasons. First, thin objects often correspond to safety-critical infrastructure. Second, boundary errors frequently propagate to downstream tasks such as tracking and planning. Yet, aggregate metrics like mIoU obscure why these failures occur and which images or structures are most affected.

This project takes a diagnostic-first approach. Rather than focusing solely on improving global performance, we first analyze segmentation difficulty across models and images to identify systematic weaknesses. Motivated by this analysis, we propose a SAM3-guided boundary supervision strategy that distills geometric priors from a large foundation model into a lightweight semantic segmentation network.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1 Semantic Segmentation in Urban Scenes

Early semantic segmentation approaches relied on hand-crafted features and graphical models such as Conditional Random Fields. While effective at modeling local boundaries, these methods struggled with semantic consistency at scale.

The introduction of fully convolutional networks (FCNs) enabled end-to-end semantic segmentation, later improved by architectures such as DeepLab through atrous convolutions and multi-scale context. More recently, transformer-based models such as SegFormer have demonstrated strong performance by modeling long-range dependencies with efficient attention mechanisms [2].

Despite these advances, boundary precision remains a known weakness, particularly for thin or elongated structures.

2.2 Mask-Based and Universal Segmentation Models

Mask-based architectures, such as Mask2Former, unify semantic, instance, and panoptic segmentation through mask classification. These methods improve object delineation but are computationally heavier and less suitable for lightweight deployment.

2.3 Foundation Models and Geometric Priors

Foundation models such as the Segment Anything Model (SAM) and its successor SAM3 are trained on large-scale data to produce high-quality object masks with strong geometric fidelity [4]. However, these models are class-agnostic and are not directly optimized for semantic segmentation benchmarks.

Recent work suggests that such models can act as teachers, providing structural priors that complement task-specific learners.

3. Cross-Model Difficulty Analysis Framework

3.1 Motivation

Standard evaluation metrics fail to explain where and why segmentation models fail. To address this limitation, we introduce a framework for analyzing segmentation difficulty at the image level across multiple architectures.

3.2 Difficulty Clustering

For each image in the validation set, we compute a performance vector containing per-class IoU scores from multiple models. We then apply simple clustering methods to group images by shared difficulty patterns based on their per model IoU.

The resulting clusters were observed as:

- Universally Easy: all models perform well

- Universally Hard: all models fail

- Model-Specific: performance varies by architecture

- Ambiguous: inconsistent or unstable behavior

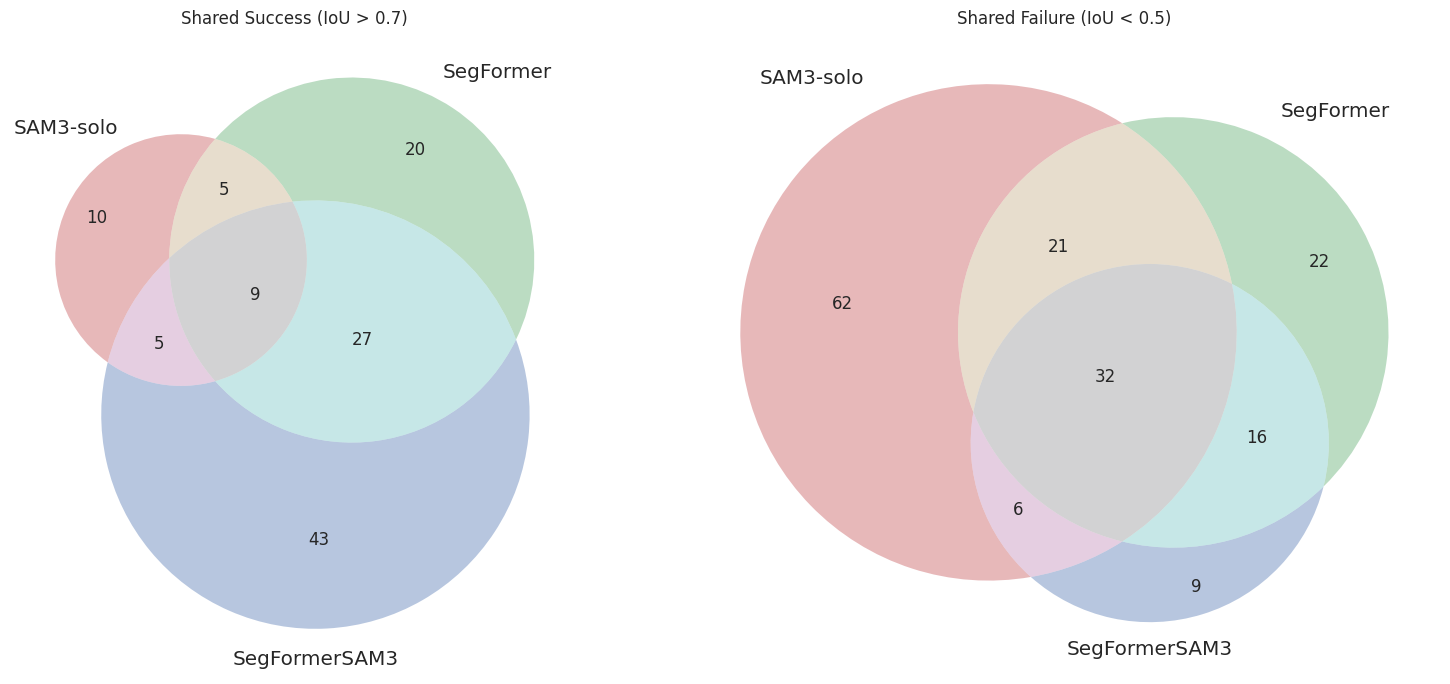

Fig 3. Venn Diagram Analysis of Model Consensus on Thin Object Classes. Comparison of successful predictions (IoU > 0.6) and failure cases (IoU < 0.5) across SAM3-solo, SegFormer (Baseline), and our proposed SegFormer+SAM3 method. (Left) Shared Success: Our method (blue) not only retains the majority of baseline successes (102 shared instances) but also uniquely correctly segments 59 difficult instances that both the standalone SegFormer and SAM3 failed to capture. (Right) Shared Failure: The proposed method demonstrates superior robustness, having the fewest unique failures (9) compared to SAM3-solo (62) and SegFormer (22), indicating that the boundary supervision effectively corrects errors inherent to the individual models.

3.3 Attribute and Pattern Analysis

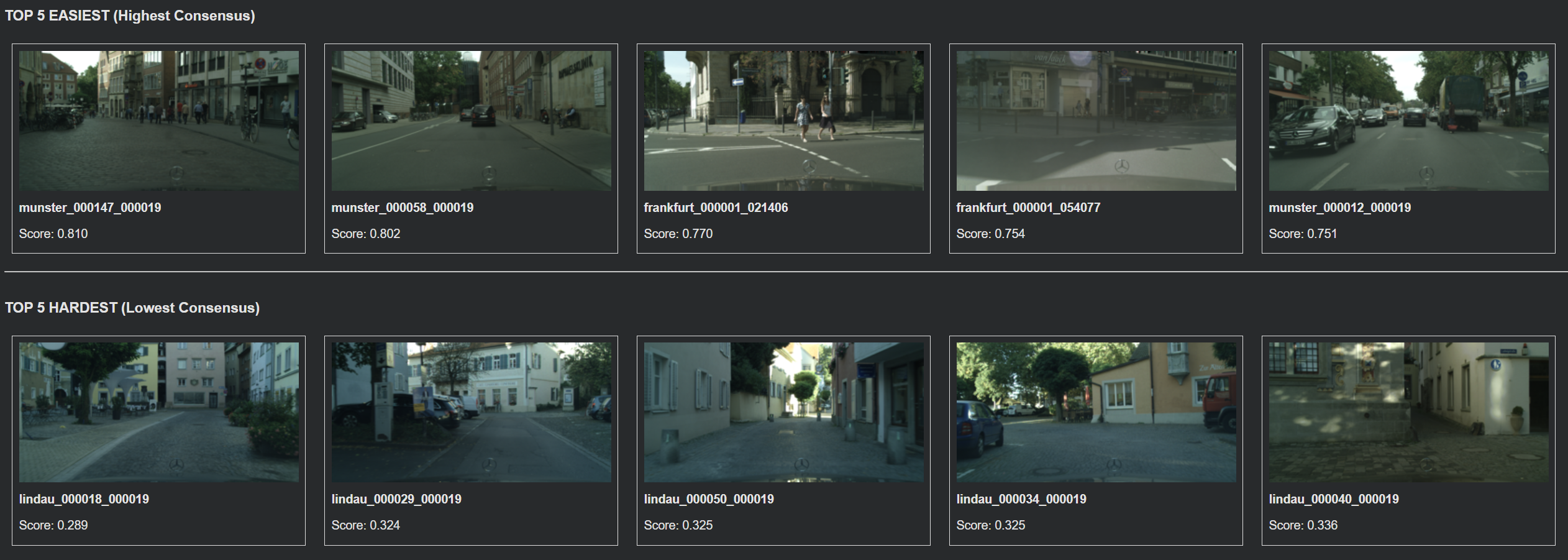

Fig 4. Top row is 5 images from the 'Universally Easy' category on top with the lowest loss—highest IoUs—and bottom row is 5 images from the 'Universally Hard' category that includes images that collectively had some of the lowest performance independent of model.

We manually analyzed correlations between difficulty clusters and image attributes such as object size, occlusion, clutter, and boundary density. This analysis revealed that thin structures and boundary-heavy scenes are overrepresented in hard clusters, particularly for transformer-based models. In the ‘hardest’ of images, it seems a mix of poor lighting and low resolution features

4. Improving the Baseline: OHEM and Oversampling

To establish a stronger baseline and address the inherent class imbalance in urban scene segmentation, we implemented a variant of SegFormer enhanced with Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM) and targeted oversampling [5].

4.1 Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM)

Standard cross-entropy loss often gets dominated by easy examples (e.g., road, sky) which comprise the majority of pixels. OHEM [5] addresses this by selecting only the top \(k\) pixels with the highest loss values for backpropagation. This forces the model to focus on difficult regions—often boundaries and thin structures—where predictions are uncertain.

\[\mathcal{L}_{OHEM} = \frac{1}{N_{hard}} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{P}_{hard}} -\log(p_{y_i})\]where \(\mathcal{P}_{hard}\) represents the set of pixels with the highest loss.

4.2 Thin Object Oversampling

Thin classes such as poles, traffic signs, and bicycles are severely underrepresented in the Cityscapes dataset. To counter this, we employ an oversampling strategy where images containing these rare classes are sampled more frequently during training. This ensures the model sees enough examples of thin structures to learn robust features, preventing them from being ignored in favor of dominant classes.

5. Method Overview: Geometry-Aware Supervision

5.1 Design Rationale

Our analysis indicates that many segmentation failures arise not from semantic confusion, but from poor geometric localization. We therefore seek to inject geometric priors into a standard semantic segmentation model without altering its inference-time complexity. As SAM3 is a master at geometric bounding, it provides reasonable suspicion that joining SAM3 and a traditional semantic segmentation model could generate some improved results.

Fig 5. Segmented output of SAM3 from multi-prompt input, which was given as category names (e.g. 'cars', 'poles').

5.2 Why SAM3?

SAM3 provides high-quality, class-agnostic object boundaries learned from large-scale data. Rather than using SAM3 directly for semantic segmentation, we employ it as a frozen geometry teacher during training. As you can see in Figure 5, SAM3 does a great job at segmenting “anything” but that does come at the cost of not easily combining categories into the general Cityscapes categories.

5.3 Key Idea

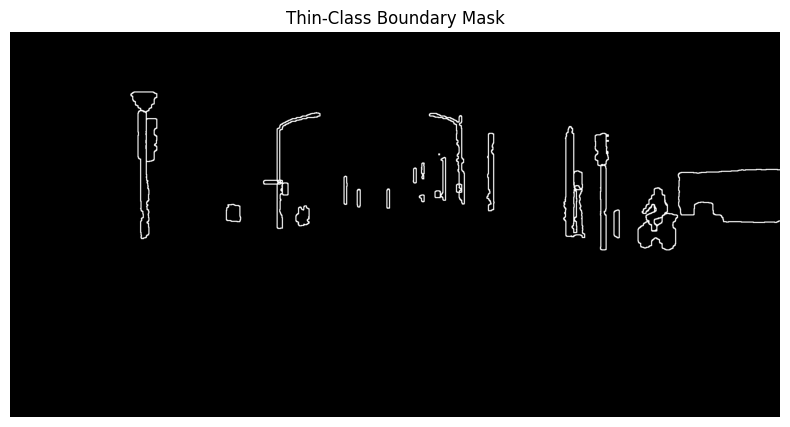

We augment SegFormer with an auxiliary boundary prediction task. During training, the model learns to:

- Predict semantic labels (standard objective)

- Predict object boundaries aligned with SAM3 outputs (auxiliary objective)

Importantly, this auxiliary loss is applied only to thin and boundary-sensitive classes, preventing over-regularization of large regions.

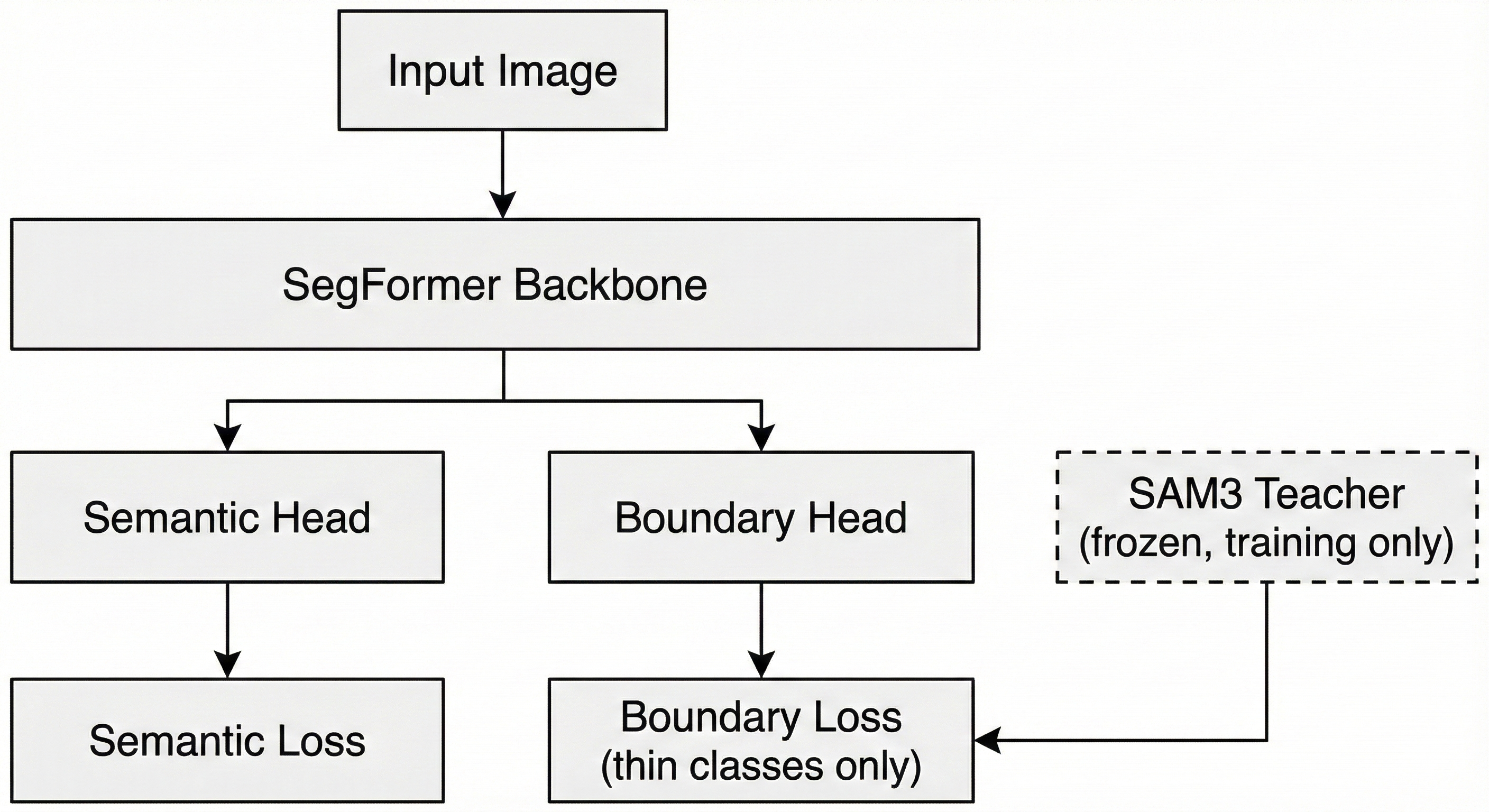

6. Model Architecture

6.1 High-Level Architecture

Fig 6. High level architecture of SAM3 guided SegFormer

The proposed system consists of:

- A SegFormer backbone (MiT-B1)

- A standard semantic segmentation head

- An auxiliary boundary prediction head

- A frozen SAM3 model used to generate boundary targets

At inference time, only the SegFormer model is used.

Fig 7. PyTorch Module definition for our Guided SegFormer.

6.2 Boundary Head

The boundary head is a lightweight convolutional module attached to intermediate feature maps. It predicts a boundary probability map supervised by edges extracted from SAM3 masks.

The total training loss is:

\[\mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}_{seg} + \lambda \mathcal{L}_{boundary}\]where \(\mathcal{L}_{boundary}\) is applied only on pixels belonging to thin classes.

Fig 8. Example boundary target generated by SAM3.

7. Implementation Details

7.1 Framework and Tools

- PyTorch

- HuggingFace Transformers

- Cityscapes dataset API

7.2 Data Preparation

- Cityscapes class mapping

- Thin-class mask generation

- SAM3 boundary extraction and binarization

7.3 Training Strategies

- Baseline SegFormer training

- Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM)

- Oversampling of underrepresented classes

- SAM3-guided auxiliary supervision

8. Experimental Setup

8.1 Dataset

Experiments are conducted on the Cityscapes dataset using the official train/validation split.

8.2 Models Evaluated

- SegFormer (B1)

- SegFormerOHEM

- Mask2Former

- DDRNet-23 Slim

- SAM3 (zero-shot evaluation)

- SAM3-Guided SegFormer (proposed)

8.3 Metrics

- Per-class IoU

- Mean IoU

- Thin-class focused analysis

9. Results

9.1 Quantitative Results

We evaluate all models on the Cityscapes validation set using mean Intersection-over-Union (mIoU) and per-class IoU. Results are reported for standard semantic segmentation models, zero-shot SAM3, and our proposed SAM3-guided SegFormer variants.

Overall Performance Comparison

| Model | mIoU ↑ |

|---|---|

| DDRNet-23 Slim | 76.83 |

| SegFormer + OHEM (Ours) | 73.45 |

| SegFormer + SAM3 Boundary (Ours) | 73.32 |

| SegFormer | 70.95 |

| Mask2Former | 64.53 |

| SAM3 (Zero-shot) | 62.14 |

Table 1. Mean IoU comparison across evaluated models on the Cityscapes validation set.

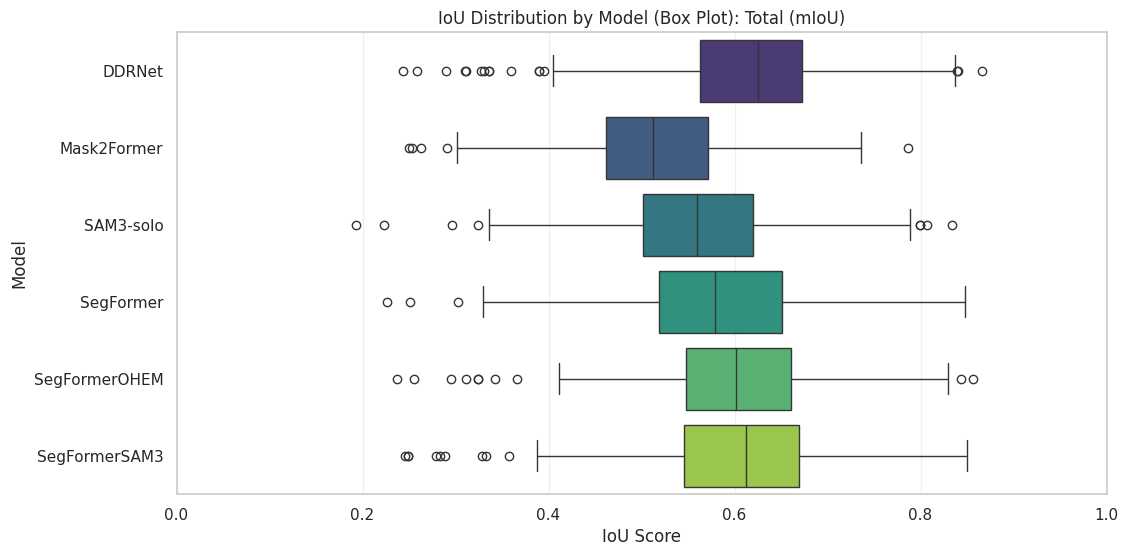

Fig 9. Box and Whisker plot equivalent of Table 1.

DDRNet-23 Slim achieves the highest overall mIoU (76.83%), reflecting its strong inductive bias toward preserving fine spatial detail through a dual-resolution architecture. However, this performance comes at the cost of architectural specialization and reduced flexibility compared to transformer-based models.

Among transformer-based approaches, SegFormer serves as a strong baseline but lags behind both of our finetuned variants. SegFormer with Online Hard Example Mining (OHEM) achieves the highest mIoU among SegFormer variants (73.45%), indicating that emphasizing difficult samples improves global robustness. The proposed SAM3-guided SegFormer achieves a comparable mIoU (73.32%) while specifically targeting boundary-related failure modes, as discussed next.

Mask2Former and zero-shot SAM3 trail behind due to, respectively, heavy architectural overhead and lack of semantic supervision.

Impact of SAM3 Boundary Supervision on Thin Classes

To isolate the effect of geometry-aware supervision, we compare SegFormer against its SAM3-guided counterpart on thin and boundary-sensitive classes.

| Class | SegFormer | Our Hybrid | Δ IoU |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pole | 51.49 | 56.06 | +4.57 |

| Fence | 51.84 | 55.73 | +3.89 |

| Traffic Light | 61.06 | 66.53 | +5.47 |

| Traffic Sign | 71.66 | 75.37 | +3.71 |

| Rider | 37.35 | 52.51 | +15.16 |

| Motorcycle | 47.29 | 61.22 | +13.93 |

| Bicycle | 69.62 | 73.46 | +3.84 |

Table 2. Per-class IoU improvements obtained by SAM3-guided boundary supervision on thin and boundary-sensitive categories.

The proposed SAM3-guided SegFormer improves mean IoU by +2.37 over the baseline SegFormer, with gains concentrated almost exclusively on thin and boundary-dominated classes. The most pronounced improvements are observed for rider (+15.16) and motorcycle (+13.93), classes characterized by overlapping instances and ambiguous boundaries.

These results strongly support the central hypothesis of this project: injecting geometric priors via boundary supervision disproportionately benefits thin and overlapping objects, which are poorly served by region-based losses alone.

Cross-Model Comparison on Thin Structures

We further compare performance on thin classes across all evaluated models to contextualize the improvements.

| Class | SegFormer | SegFormer OHEM | SegFormer + SAM3 | DDRNet-23 | Mask2Former | SAM3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wall | 51.08 | 54.12 | 55.50 | 51.33 | 54.95 | 42.63 |

| Fence | 51.84 | 55.42 | 55.73 | 61.48 | 43.25 | 54.71 |

| Pole | 51.49 | 53.41 | 56.06 | 58.11 | 39.15 | 58.37 |

| Traffic Light | 61.06 | 64.20 | 66.53 | 67.96 | 47.58 | 69.71 |

| Traffic Sign | 71.66 | 74.12 | 75.37 | 75.20 | 61.54 | 68.34 |

| Rider | 37.35 | 51.16 | 52.51 | 62.19 | 37.02 | 8.30 |

| Motorcycle | 47.29 | 56.83 | 61.22 | 59.68 | 27.24 | 72.11 |

| Bicycle | 69.62 | 72.53 | 73.46 | 75.53 | 60.65 | 57.85 |

Table 3. Per-class IoU comparison across models for thin and boundary-sensitive categories.

DDRNet-23 Slim consistently performs well on thin structures due to its architectural emphasis on high-resolution features. However, the SAM3-guided SegFormer closes much of this gap while retaining the flexibility and efficiency of a transformer-based backbone.

Zero-shot SAM3 achieves high IoU on some thin classes (e.g., motorcycle) but performs poorly on semantic consistency, especially for rider and terrain-related categories. This reinforces the conclusion that SAM3 is best leveraged as a geometry teacher rather than a standalone semantic segmentation model.

Importantly, large “stuff” classes such as road, building, vegetation, and sky (not shown) remain stable across SegFormer variants, indicating that thin-class-only boundary supervision avoids over-regularization. A regression is observed for the train class in the SAM3-guided model, likely due to class rarity and ambiguous boundaries, and is discussed further in the limitations section.

Together, these results demonstrate that distilling geometric knowledge from a foundation model into a lightweight segmentation architecture yields targeted, interpretable improvements on known failure modes without increasing inference-time complexity.

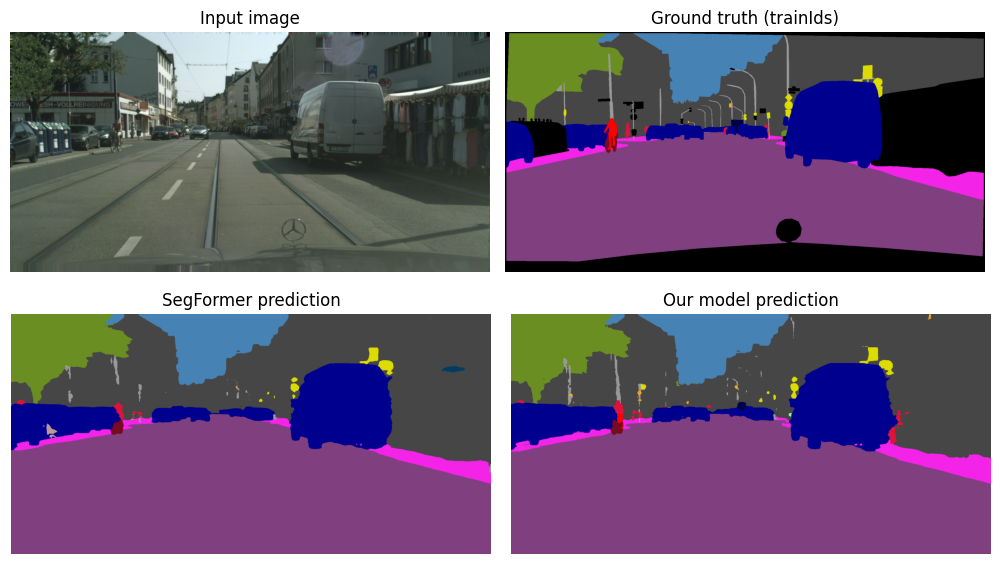

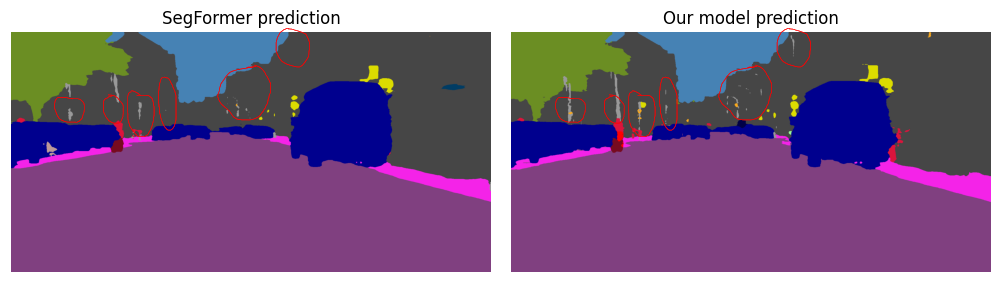

9.2 Qualitative Results

Qualitative comparisons reveal sharper boundaries, improved instance separation, and reduced fragmentation in complex scenes. Although the difference in IoU isn’t ground breaking, with only 5 epochs of training and a batch size of 8 images on an A100 GPU, there are substantial visible markers of emerging improved recognition of these difficult objects as seen in Figure 10.

Fig 10. Side-by-side segmentation outputs for baseline vs SAM3-guided model. Middle left is SegFormer results. Middle right is our SAM3-Guided SegFormer results. Bottom row highlights specific regions of improvement.

10. Analysis and Observations

- Boundary supervision yields targeted improvements without degrading large classes

- Rider and motorcycle classes benefit most

- A regression on the train class is observed and discussed in context of class rarity and boundary ambiguity

11. Limitations

- SAM3 introduces additional training-time computational cost

- Boundary supervision does not fully resolve all thin-object errors

- A dedicated thin-object benchmark was proposed but not fully implemented

12. Conclusion

This project demonstrates that difficulty-aware analysis can reveal systematic weaknesses in semantic segmentation models. By distilling geometric priors from SAM3 into SegFormer through auxiliary boundary supervision, we achieve targeted improvements on thin and boundary-sensitive classes without increasing inference cost.

13. Future Work

13.1 Adaptive, class-aware auxiliary supervision

Currently, we use the same weight for the boundary auxiliary loss across all thin classes. However, our error analysis showed that classes with unclear internal textures, like Train, had more mistakes. In the future, we could try adaptive auxiliary weighting, where the boundary supervision strength changes based on the model’s uncertainty or the object’s size. This approach could help avoid breaking up large, rare objects too much, while still keeping high accuracy for small, thin structures.

13.2 Temporal consistency in video segmentation

Urban perception is naturally a video task, but our current evaluation looks at each frame separately. Thin objects, such as poles and traffic signs, often appear to flicker between frames in standard models. A logical next step is to add temporal consistency constraints, using optical flow or temporal attention modules, to help our model keep sharp boundaries stable over time.

13.3 Dedicated thin-object evaluation benchmarks

Future research should create dedicated thin-object benchmarks to rigorously test model performance on safety-critical structures. Evaluating on large-scale datasets needs a more efficient pipeline. Right now, our method relies on offline pre-computation, which uses a lot of storage. Switching to an online distillation framework with lighter foundation models like MobileSAM would let us scale our method to these benchmarks using regular consumer hardware, without the storage bottleneck.

13.4 Boundary-specific metrics

Standard mIoU often hides improvements in fine geometric details. To better measure progress, we suggest using and standardizing Boundary IoU (BIoU) or Trimap-based metrics for urban benchmarks. These metrics would directly penalize alignment errors along object edges, giving a fairer and more safety-focused evaluation of segmentation models for autonomous driving.

References

[1] Cordts, M., et al. The Cityscapes Dataset for Semantic Urban Scene Understanding. CVPR, 2016.

[2] Xie, E., et al. SegFormer: Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers. NeurIPS, 2021.

[3] Cheng, B., et al. Masked-attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation. CVPR, 2022.

[4] Kirillov, A., et al. Segment Anything. ICCV, 2023.

[5] Shrivastava, A., et al. Training Region-Based Object Detectors with Online Hard Example Mining. CVPR, 2016.