Membership Inference Attacks against Vision Deep Learning Models

Membership Inference Attacks (MIA) are privacy attacks on machine learning models meant to predict whether or not a a data point was used to train a model. This blog looks at three different MIA methods against three different types of models.

- Introduction

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

- Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP)

- Diffusion

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

With the widespread commercialization and use of machine learning and deep learning models, privacy risks have consequently become a rising concern. A Membership Inference Attack (MIA) is a form of privacy attack performed against a model to determine if a data point was used in training a specific model. In the context of computer vision and deep learning, these attacks are primarily concerned with whether or not a specific image was included in the training dataset. The basis for most MIA methods relies on the fact that machine learning models typically overfit to the training data. This discrepancy between the model’s performance on the training data and unseen data exposes the model to such a privacy attack. Therefore, a successful MIA can expose vulnerabilities of a model, such as training data memorization, overfitting, and most importantly, data leakage. However, as models become more complex, robust, and diverse, various new methods are constantly being researched to improve the performance of these MIA attacks. This report aims to explore several Membership Inference Attack methods against three different types of models. Specifically, MIAs for Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining model (CLIP), and diffusion models will be discussed.

Membership is defined as being a part of, or a “member” of the training data. Essentially, if an image was used in the training data, that image is a member; on the other hand, if the image was not used for training, then the image is a non-member. Furthermore, a target model is defined as the model that is being attacked, while an attack model is a binary classification model used for predicting membership.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)

“Membership Inference Attacks Against Machine Learning Models” by Shokri et al. (2017)[4] is one of the most prominent and pioneering papers in this form of privacy attacks. Shokri et al. (2017) proposes an approach using shadow models to predict membership of images used to train convolutional neural networks (CNN).

Target Model

Although the paper utilizes various datasets, including tabular datasets, to keep it relevant to the course, this report will focus on the CIFAR datasets. For both the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100, a standard convolutional neural network (CNN) with two convolution and max pooling layers, a fully connected layer of size 128, a softmax layer, and Tanh activation was designed as the target model.

Assumptions

The approach is based on the black-box assumption. This means that the attacker does not have access to any parameters of the target model, nor the actual training data itself. The only access provided is an auxiliary dataset (a dataset that has a similar statistical distribution to the real training data) and the output vector from the target model. This is crucial in cases where an attacker may only rely on a model’s API, rather than having access to the model itself, to query the output from an input image. In this specific paper, the attacker only relies on the softmax probabilities outputted from the target model, and nothing more.

Method

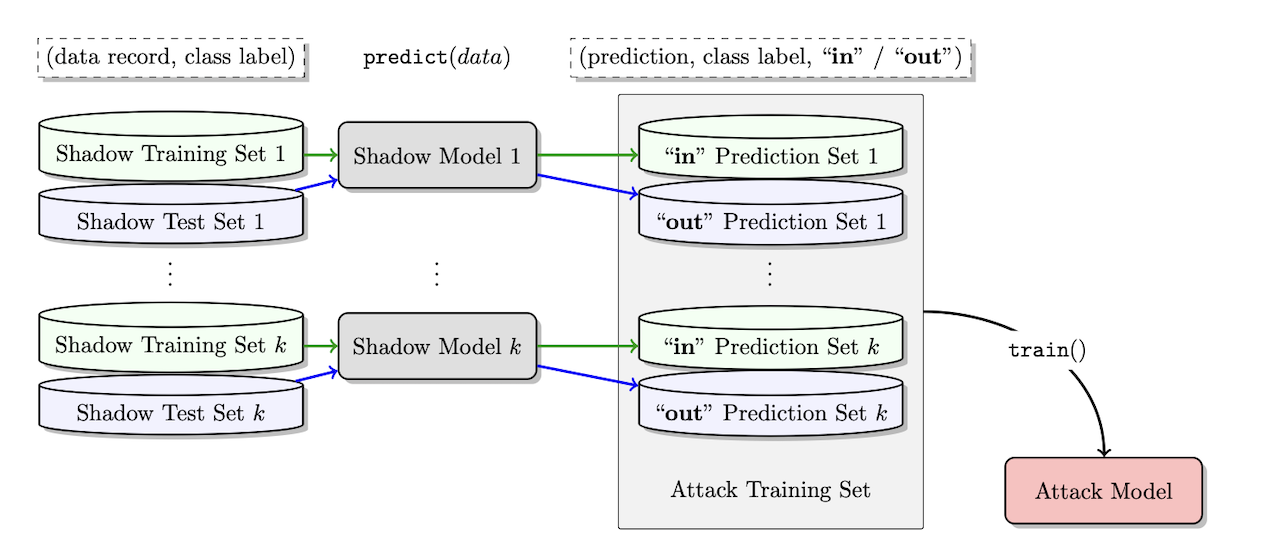

First, the auxiliary dataset is obtained, whether this is through synthetic data or through real data. This data is assumed to be completely separate from the actual training data of the target model. The data is then bootstrapped into k different datasets. Each dataset is then split into a training and testing dataset. Using this data, k models of the same architecture as the target model are individually trained using their respective training data. These models are referred to as shadow models. After training, the outputs from each shadow for their respective training and testing data are collected and concatenated with a corresponding label (1 if the data is a member and 0 if the data is a non-member). All the results are then split into separate datasets depending on the class label. For example, all data points with class label ‘airplane’ are combined into one dataset, all data points with class ‘bird’ are combined into another dataset, etc. For each dataset, the softmax probabilities are the features and its membership is the feature. Using this dataset, a completely new model–an attack model, is trained for each class label. The attack model takes the softmax probabilities as inputs to perform a binary classification task, determining whether the data is a member or a non-member.

Fig 1. Auxiliary data is used to train Shadow Models, which are used to train an Attack Model [4].

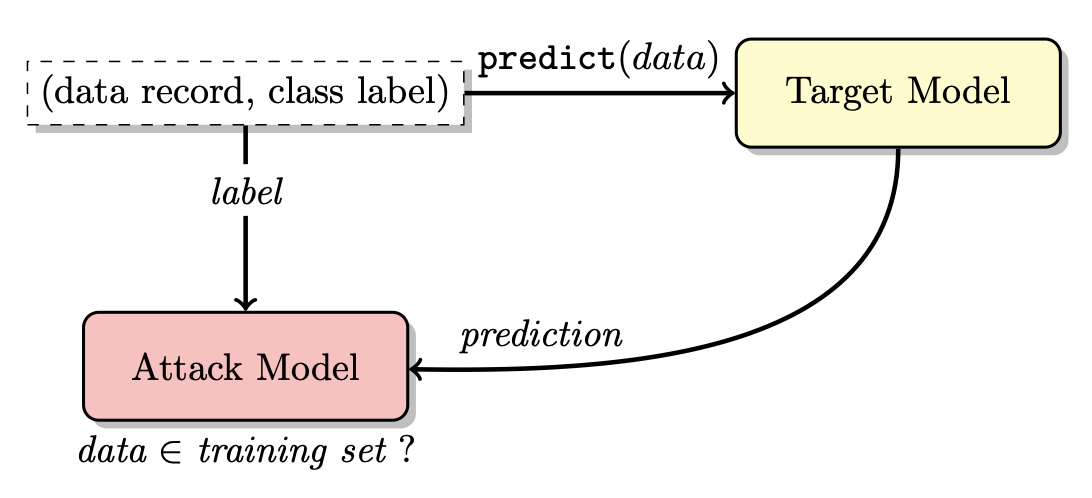

Finally, once the attack model is trained, the target model is queried with the data in question to obtain its softmax probabilities. These probabilities are then fed into the corresponding attack model based on the predicted class label to classify membership.

Fig 2. The Attack model uses the Target model outputs to predict Membership [4].

This attack method utilizes the over confidence of models on already seen data. Models are more likely to have higher confidence scores when predicting the class of an image they have been trained on, whereas they are more likely to be less confident in their predictions on unseen data. This discrepancy allows for a successful MIA.

Results

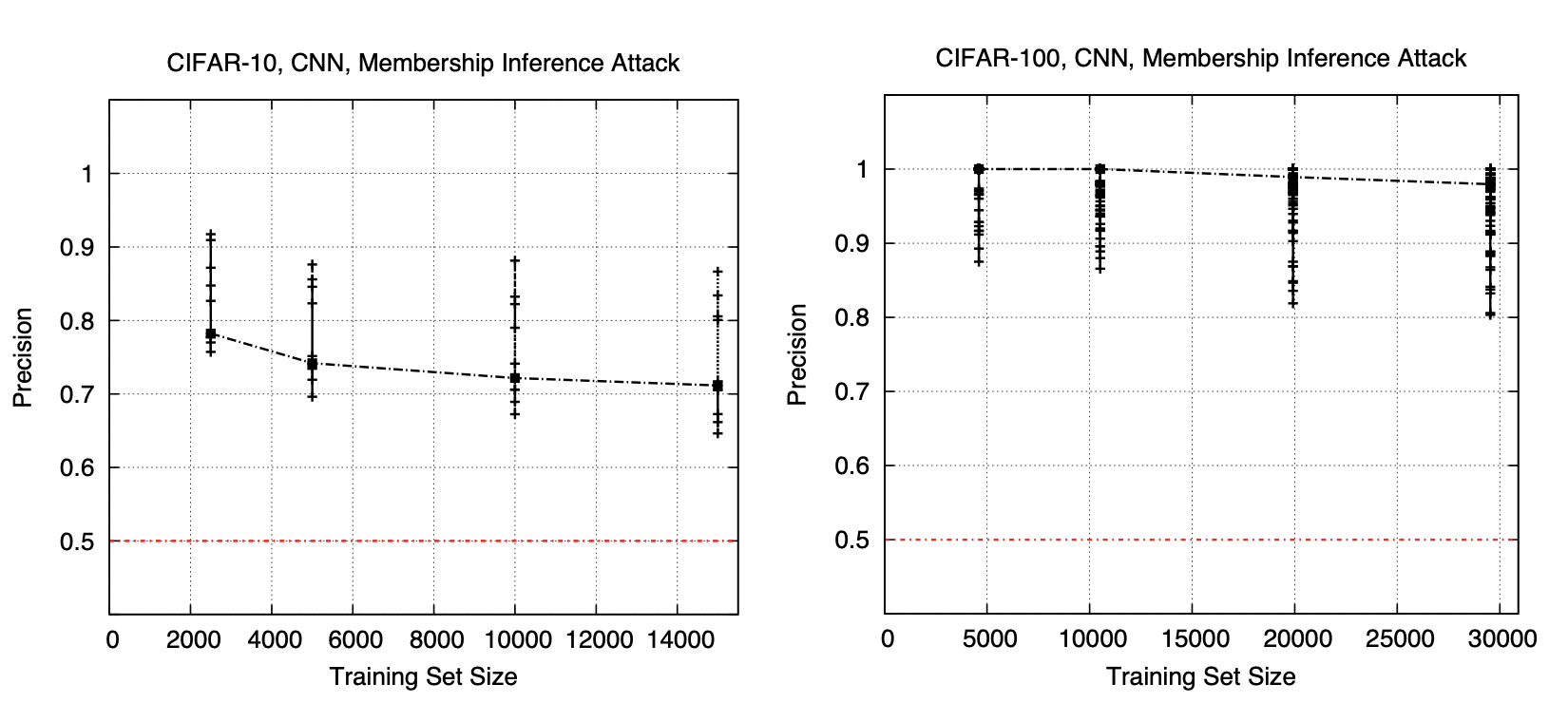

Fig 3. Precision for both CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 against the training data size [4].

Precision was chosen as the metric to evaluate the performance of the MIA. Essentially, the proportion of actual members from the total number of images predicted as members were assessed. Looking at the figure above, it is evident that the precision was in fact very high for both the CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The paper also mentions that recall was nearly 1.0 for both datasets.

The above results also demonstrate that the attack performs better on the CIFAR-100 dataset than the CIFAR-10 dataset. Based on this, it can be inferred that more classes contribute to more leakage. Because the attack model relies on the probability vector of the target model, more classes allows the attack model to have more information about the target model. This in turn helps the attack model perform better.

Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining (CLIP)

“Practical Membership Inference Attacks Against Large-Scale Multi-Modal Models: A Pilot Study” by Ko et al. (2023) dives into attacking self-supervised vision language models, specifically the CLIP model.

Target Model

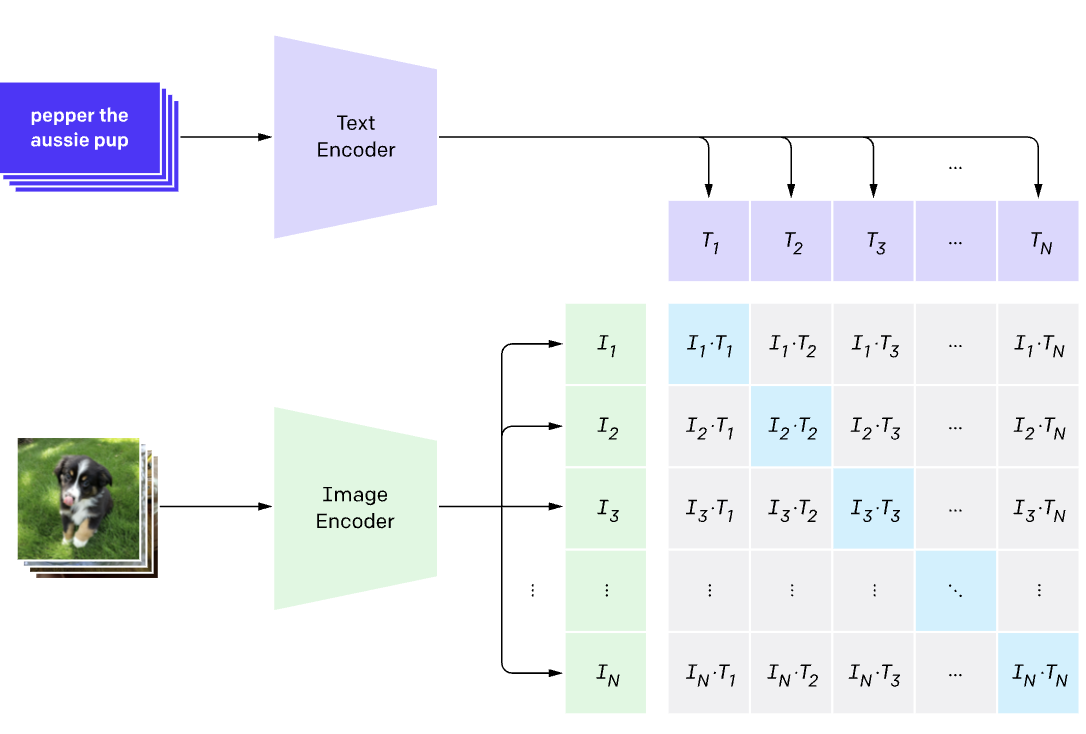

The CLIP model utilizes two different encoders: one for images and one for text. Using these images, the CLIP model learns to connect matching images with the corresponding text. The model uses contrastive learning, which utilizes cosine similarity to maximize the similarity between correct image-text pairs while minimizing the similarity between incorrect image-text pairs.

Fig 4. CLIP model [3].

For the image backbone of the target CLIP models, ViT-B/32, ViT-B/16, and ViT-L/14 are used for the LAION dataset while ResNet50, Resnet101, and ViT-B/32 are used for the CC12M dataset.

Assumptions

Similar to the first paper, black-box access is assumed in this research as well. The attacker is able to query the model with a pair of image and text, and obtain the corresponding encoded features. It is assumed that the attacker is unaware of the model architecture, parameters, etc. The first two attack methods also assume that the attacker has no knowledge on the real training dataset.

Method

The paper proposes three different methods in this paper.

Cosine-Similarity Attack (CSA)

This attack relies on the basis that models trained with contrastive learning focus on maximizing cosine similarity. In this simple attack, the cosine similarity scores are compared using a threshold. The cosine similarity between the image and its respective text is calculated. If this score is above a certain, predefined threshold, then the data is predicted to be a member, and vice versa.

Augmentation-Enhanced Attack (AEA)

In this second attack, several different transformations are performed on each input image. Then, the cosine similarity between the text and the transformed image are calculated, and the cosine similarity gap, or the difference in cosine similarity from the original image and the text are collected. Finally, these scores are aggregated and compared to a threshold to determine membership. Similar to the previous attack, if the scores exceed the threshold, they are considered a member, and vice versa.

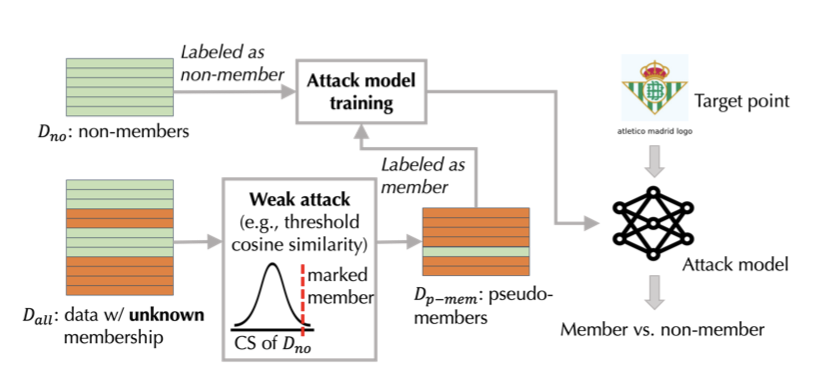

Weakly Supervised Attack (WSA)

The Weakly Supervised Attack is the most promising attack proposed in this paper. However, this method relies on a different assumption regarding the data compared to the last two attacks. When attacking models trained on public internet data, it can be easily assumed that data uploaded after the publication of the model are definitely non-members. Using this knowledge, the mean and standard deviation of the cosine similarities of the model outputs on these guaranteed non-members are calculated. Then, from a very large dataset containing both non-members and members, data whose cosine similarities are greater than $\mu_{no} + \lambda \sigma_{no}$, where $\mu_{no}$ is the mean of the non-member data and $\sigma_{no}$ is the standard deviation of the non-member data, are collected as pseudo-members. It is assumed that image-text pairs with a much higher cosine similarity are outliers, and therefore can be excluded from being a non-member. The encoded features for the images and texts for both psuedo-members and non-members, along with their corresponding binary labels (1 for member and 0 for non-member) are used to create an attack dataset. An attack model, similar to Shokri et al., is then trained using this data to predict binary membership.

Fig 5. An Overview of the proposed Weakly Supervised Attack [1].

Results

The table below shows the AUC for each attack method on each model for the LAION dataset:

| Method | ViT-B/32 | ViT-B/16 | ViT-L/4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.79 |

| AEA | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.80 |

| WSA | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

The table below shows the AUC for each attack method on each model for the CC12M dataset:

| Method | ResNet50 | Resnet101 | ViT-B/32 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA | 0.67 | 0.69 | 0.70 |

| AEA | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| WSA | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.79 |

The results above show that even the simplest cosine similarity attack demonstrates high performance on the CLIP models. However, the proposed Weakly Supervised Attack demonstrates an exceptionally high improvement and performance, especially for the LAION dataset.

Cosine similarity alone may not be enough to clearly separate member data points from non-member data points. On the other hand, because the WSA method trains an attack classifier on the features, it can be regarded as a much more complex transformation. This allows the approach to extract more meaningful relationships and separate members from non-members better, as shown through the higher performance.

Diffusion

“Towards Black-Box Membership Inference Attack for Diffusion Models” proposes a novel method for performing MIAs on various forms of diffusion models. In particular, the proposed method is compatible with just black-box access by not relying on the U-net architecture like other pre-existing approaches.

Target Model

This paper chooses to attack several different variations of diffusion models. In particular, the DDIM model, diffusion transformer model, and stable diffusion model are tested. In addition to these three models, the DALL-E 2 is also attacked using its API.

Assumptions

This research also assumes black-box access. The attack proposed relies only on the target model’s API and does not have access to any internal structure or parameters.

Method

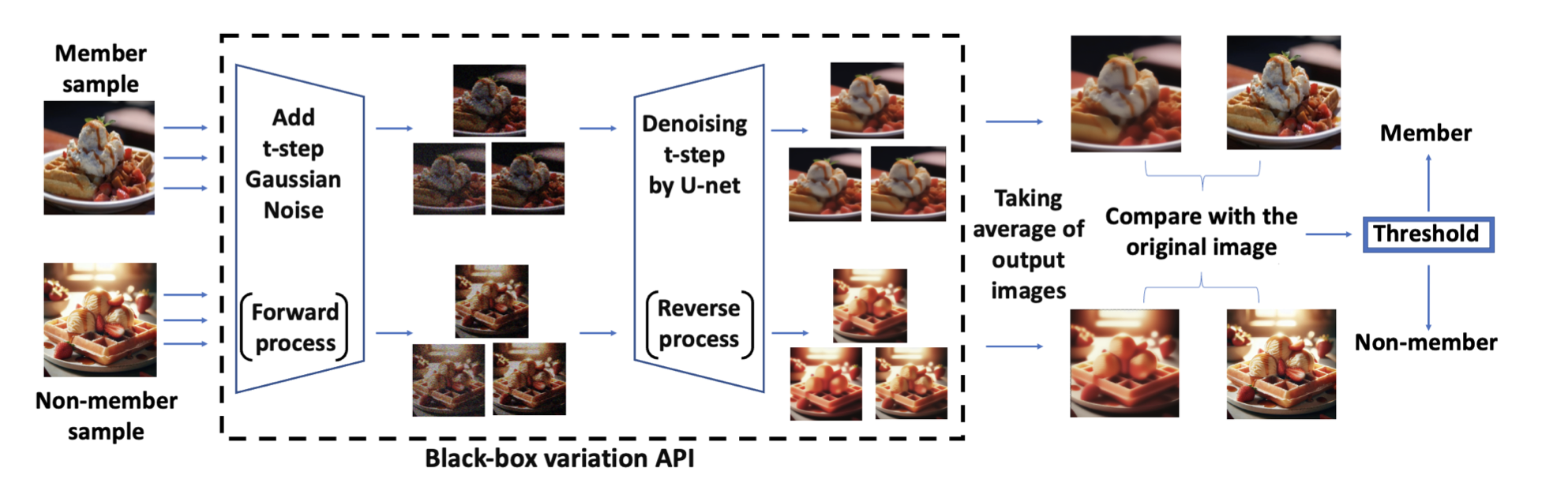

This attack method is designed on the basis that images used in training are more likely to undergo minimal changes when inputted through the diffusion process, while unseen, non-member images are more likely to undergo larger changes.

For every image, the attacker inputs the image to the selected model and repeats this several times. Each time, the model takes in the same input image, adds noise to the image, then denoises the image, and finally outputs a newly generated image. The attacker then takes the newly generated images (of the same input image) and averages the images together. The difference between this average and the original image is calculated, and if this difference is below a certain threshold, the input image is determined to be a member.

Fig 6. An Overview of the proposed ReDiffuse algorithm [2].

Results

The results for each model is shown below:

| Metric | DDIM | Diffusion Transformer | Stable Diffusion | DALLE-2 (with L1 distance) | DALLE-2 (with L2 distance) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.81 | 76.2 | 88.3 |

| ASR | 0.91 | 0.95 | 0.75 | 74.5 | 81.4 |

As shown above, the proposed attack demonstrates very high performance for all the diffusion models, validating an effective MIA. The attack’s performance on the DALLE-2 provides important insight that even popular, commercialized models can be vulnerable to privacy attacks and data leakage.

Conclusion

This blog explored three different methods for performing MIA against three different models. This demonstrates how custom methods for attacking different types of models are necessary for good performance. Overall, it is evident that the proposed methods are all very successful in performing strong attacks against their respective target models. These results leave great concerns regarding privacy risks in vision deep learning models, along with great potential for further research into defenses against such privacy attacks.

References

[1] Ko, Myeongseob, et al. “Practical membership inference attacks against large-scale multi-modal models: A pilot study.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.00108, 2023.

[2] Li, Jingwei, et al. “Towards black-box membership inference attack for Diffusion Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.20771, 2024.

[3] OpenAI, “CLIP: Connecting Text and Images,” OpenAI Blog.[Online]. Available: https://openai.com/index/clip/

[4] Shokri, Reza, et al. “Membership inference attacks against Machine Learning Models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.05820, 2017.