Pose Estimation

Pose estimation research has been growing rapidly and recent advances have allowed us to accurately detect the various joints in the human body from just a photo. Convolutional Neural Networks have been the medium for obtaining high performance models and in this post we explore the novel model HRNet. Applications of pose estimation include identifying classes of actions undertaken by individuals, their poses, and animation.

1. Introduction and Objective

1.1 Introduction

Pose estimation in humans is the process of locating key points in the human body including shoulders, knees, etc. Our project focused on 2D pose estimation which is concerned with identifying these keypoints in pictures of individuals. Specifically, our project was based on a paper that identifies the poses of individuals and not multi-person pose estimation. It has many applications including recognizing humans, their actions, animation, and more. One commonly cited example application is inferring the current action of the target. For example, by analyzing the pose of a human, we can determine if they are walking, running, or displaying another common action. The emergence of deep learning has greatly improved the capabilities of pose estimation.

1.2 Objective

In this project we use High-Resolution Net (HRNet) to be able to estimate poses of subjects. We employ the Max Planck Institut Informatik (MPII) dataset in our implementation. This dataset includes pictures of individuals in various scenarios with annotations including keypoints of their pose. In total, this dataset contains 25K images with 40k subjects. Of these, 12k subjects are reserved for testing and the remaining are for the training set. This data is crucial for our model’s predictions and will be used to evaluate its performance.

The objective of this paper is to accurately predict the key points of a pose. We hope that our model is capable of making predictions about the locations of a subject’s ankle, wrist, and other noteworthy points. Model performance is measured by comparing our predictions with the annotations provided by the MPII dataset.

Other goals include being able to discern the features that allow a model to accurately predict poses. This project will hopefully expose useful characteristics that can be applied to other applications of pose estimation. We realize that many of our results are limited by the diversity of our dataset. While the MPII dataset only includes 25K images, we hope that this is enough to achieve reasonable performance. It is undeniable that access to more data would certaintly increase the effectiveness of our model, but we limit our scope to this single dataset for practical reasons. The dataset may be unable to capture all the possible scenarios that our model may encounter in real situations, but our model should be able to identify the majority of images given to it in theory.

2. Pose Estimation With High-Resolution Learning

2.1 Original Downsampling Pipeline

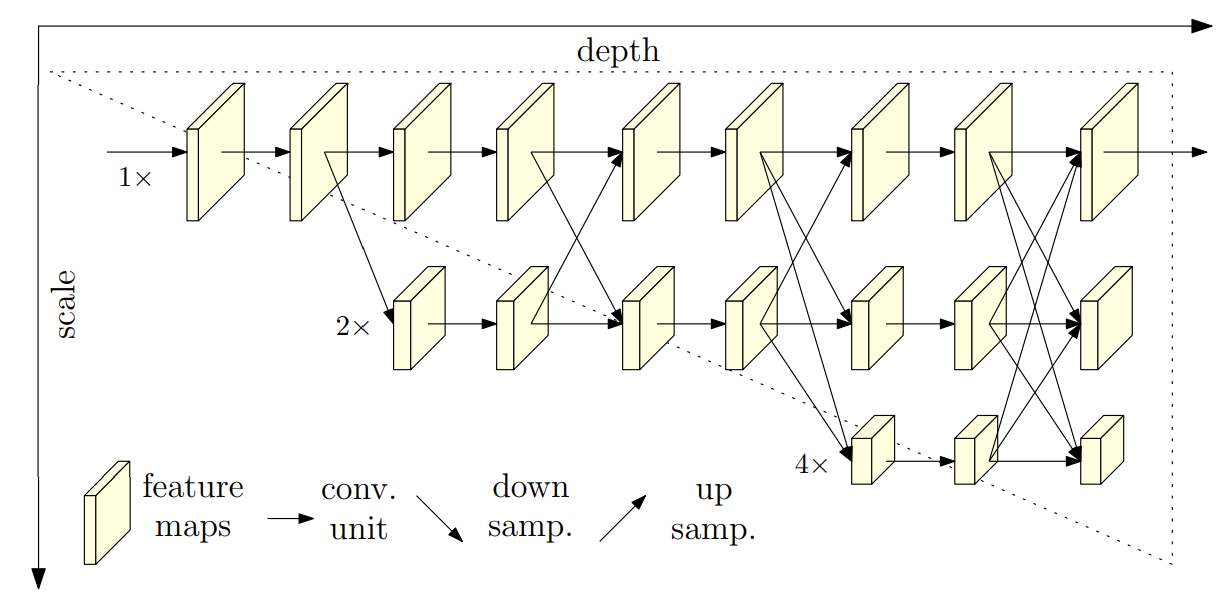

The paper “Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation” serves as the backbone for our project. It introduces the novel architecture, HRNet, which utilizes a downsampling pipeline. The high to low process generates low-resolution and high-level representations. This idea allows the model to increase its performance while retaining many of the benefits of a model that maintains the same resolution as the input. The model also has its symmetric counterpart for restoring the representations back to the high resolution that the input possesses. The low to high process is targeted at producing high resolution representations. The paper uses a few bilinear upsampling or transpose convolution layers to restore this resolution.

Fig 1. Pose Estimation using the Downsampling Pipeline [2].

2.2 Maintaining a High-Resolution Representation

The HRNet maintains the high-resolution representation by utilizing multi-scale fusion. The multi-resolution images are fed into the model and combined with the low to high process through the use of skip connections. Their implementation repeats multi-scale fusion which allows the model to retain simpler features despite the growth in its complexity. Additionally, the model is implemented with intermediate supervision. It helps the deep network train and improve the heatmap estimation quality.

The network connects high-to-low subnetworks in parallel and maintains high resolution representations with a spacially precise heatmap estimation. Most existing methods separate the low to high upsampling process and aggregate low and high level representations. The paper’s approach does not use an intermediate heatmap supervision, but is superior in keypoint detection accuracy and efficient in computation complexity and parameters. The paper uses multi-resolution subnetworks that gradually adds high to low resolution subnetworks one by one, form new stages, and connect the multi-resolution subnetworks in parallel.

3. Setup and Preparation

3.1 Environment

You can visit our Colab Notebook that we used to demo training and running the model here!.

First up, environment setup and installation! Since Google Colaboratory has many of the Python packages we need to train and test this dataset, we’ll assume that anyone replicating our work is using it. From here, the original model will be referred to as HRNet.

- Open a new Juypter Notebook file in Google Colab and start a runtime with GPU acceleration.

-

Clone the HRNet code.

!git clone https://github.com/leoxiaobin/deep-high-resolution-net.pytorch %cd deep-high-resolution-net.pytorch -

Install the repository’s required dependencies. Some dependencies in

requirements.txtmay not be available; in that case, use the most recent version. In casepipisn’t working, tryconda.!pip install -r requirements.txt -

Build the project’s C++ libraries.

%cd lib !make -

We’ll be using the MPII Human Pose Dataset for training and testing, so you’ll need to download them. First, create the directories we’ll use to store this data.

%cd .. %mkdir data %mkdir data/mpii %mkdir data/mpii/annot %mkdir data/mpii/images -

Then, you’ll need to download the annotation files.

!gdown 1QeBJFAH8JDDH1Wl5uGhreFR5hpmXfmUE -O data/mpii/annot --folder -

Finally, it’s time to download the images. This’ll take a while; it’s almost 13GB of images, after all!

!wget https://datasets.d2.mpi-inf.mpg.de/andriluka14cvpr/mpii_human_pose_v1.tar.gz !tar -C data/mpii/images -xvf mpii_human_pose_v1.tar.gz

3.2 Testing the Model

If you want to test HRNet with all of the given test data, the project has a script for that, but you’ll need to either train the model or download weights first.

%mkdir models

!gdown 14p2l1u19bLOm5p6esKyolYJyfE1_inLv -O models --folder

Here’s the script, given for one of the HRNet models trained on the MPII dataset:

!python tools/test.py \

--cfg experiments/mpii/hrnet/w32_256x256_adam_lr1e-3.yaml \

TEST.MODEL_FILE models/pytorch/pose_mpii/pose_hrnet_w32_256x256.pth

4. Proposed Ablations and Improvements

- For our ablations, we performed 2 different experiments.

- One of these experiments was to remove the batch normalization step from the model.

- For the other one we removed the batch normalization and replaced the activation functions with the identity function.

5. Results and Analysis

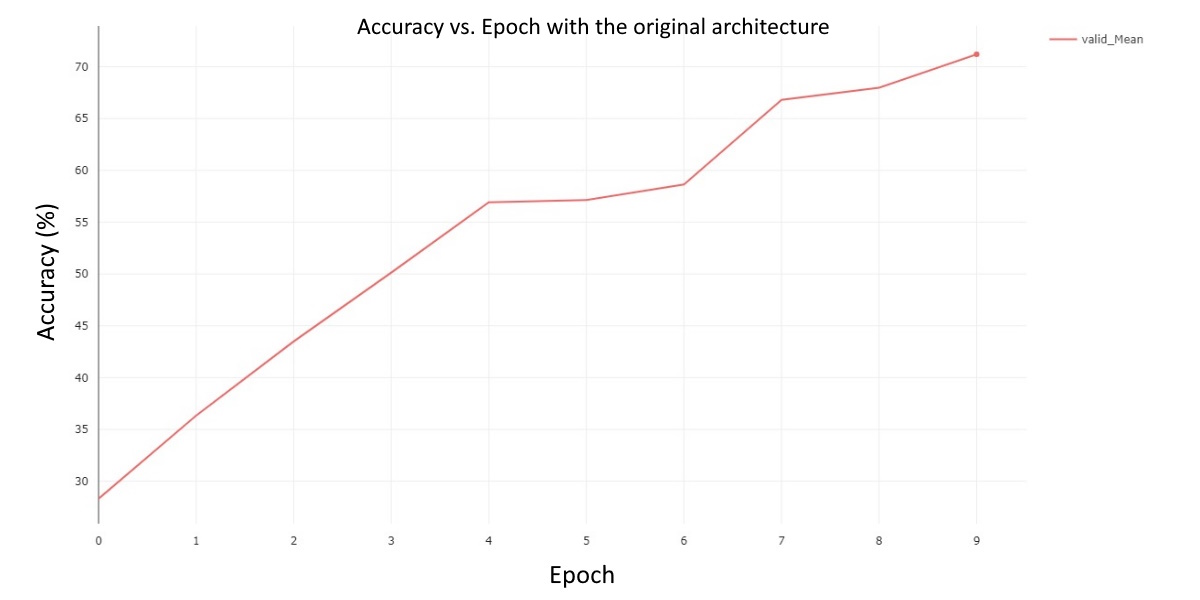

We have used the discussed HRNet and observed some results from the model described in the paper and from our 2 proposed ablations. Using the same dataset provided in the paper, we were able to perform pose estimation and have averaged our results across all joints on the validation set. In total, we trained the model for 9 epochs for all three experiments due to limitations on hardware. The results for the default model are summarized in the following chart:

Fig 2. Validation Mean Accuracy vs. Epoch for the default HRNet model.

This chart does an excellent job highlighting the average performance of our model while training it for 9 epochs. There are several notable takeaways from the graph. For one, our validation mean never regresses, which is to be expected. Secondly, after the fourth epoch, the model’s performance begins to improve at a much slower rate in general. Lastly, by the final epoch, our model reaches a mean average validation accuracy of around 70%. Now that we know how our model performs normally, we can evaluate how well our modifications perform in comparison. Our first ablation was to explore the performance of the model after removing batch normalization from the model’s architecture. The results are in the following chart:

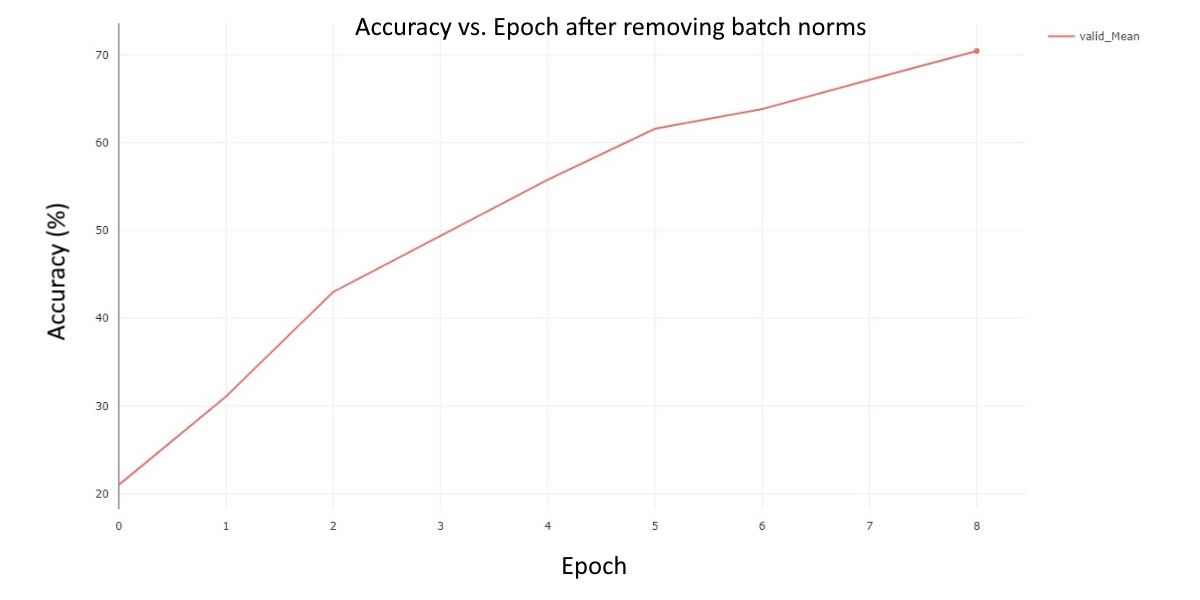

Fig 3. Validation Mean Accuracy vs. Epoch for the model with batch normalization removed.

This chart reveals several key observations about this experiment. First, the model seems to consistently improve by the same rate at every epoch. Secondly, the model’s performance reaches around 70% by the last epoch. However, it is likely that if we were to train the model for additional epochs, our performance would increase. Next, we can look at the last ablation. Our second and final ablation was to observe performance of the model after removing both batch normalization and the activation functions. The results are:

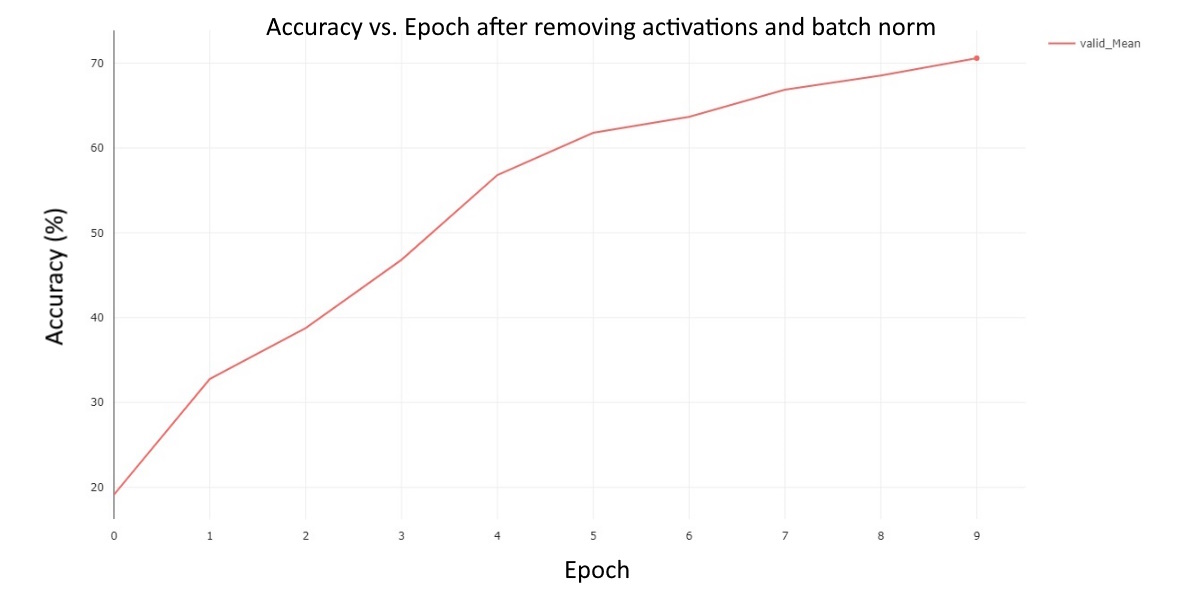

Fig 4. Validation Mean Accuracy vs. Epoch for the model with both batch normalization and activations removed.

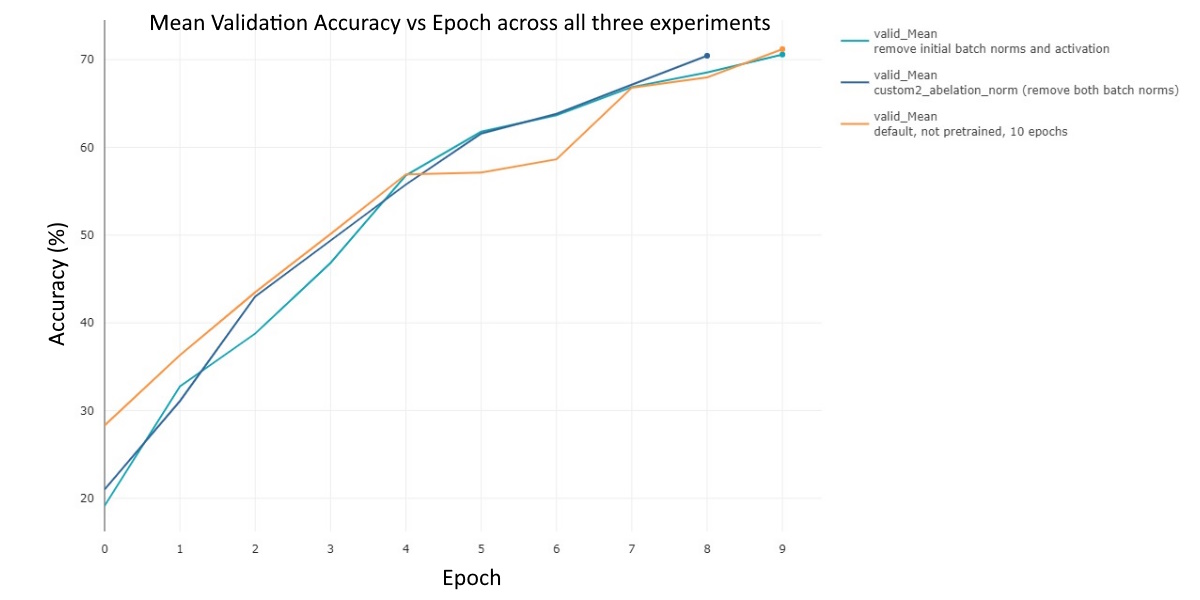

This graph allows us to gain a better insight into how the model is performing throughout the various epochs. For one, as the epochs progress, it seems that the model performs better at a decreasing rate. Secondly, the model reaches a performance of 70% at epoch 9. For better comparison, we can also directly compare these experiments by plotting them on the same chart. This is best seen here:

Fig 5. Validation Mean Accuracy vs. Epoch across all three experiments.

There are some interesting explanations that can be derived from this graph. Firstly, all three models actually reach about the same performance of 70% by the final epoch. Secondly, in all three experiments the validation mean never regresses. Lastly, the performance of the different experiments is never more than about ~8% at any individual epoch.

It seems that the ablations did not affect the performance in a significant way. This suggests that the activation functions and batch normalization do not have a notable impact on the performance of the model HRnet. However, it is likely that we did not the train the model for a long enough amount of time in order for the batch normalization and activation functions to have had a major impact on the performance. If we had instead trained the model for more than 30 epochs, we may have seen that the model’s performance degraded significantly as a result of our modifications. We do not necessarily know if this is the case here though. It is possible that the results would not change even if we increased the training time to 30+ epochs.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, we explored the architecture of HRnet in this post and its use in pose estimation. We have shown this model is capable of predicting the location of joints in humans with an impressive accuracy. The architecture of the model relies on several innovative ideas to maintain these results while dealing with high resolution images. Notably, the model takes advantage of the high to low and low to high stages. In addition, we also explored two ablations that were designed to test the architecture choices of the model. Ultimately, we showed that our model’s performance was not impacted by these modifications in a meaningful way.

References

[1] Cao, Zhe, et al. “OpenPose: Realtime Multi-Person 2D Pose Estimation using Part Affinity Fields.” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 2019.

[2] Sun, Ke, et al. “Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Human Pose Estimation.” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2019.

[3] Güler, Rıza Alp, et al. “DensePose: Dense Human Pose Estimation In The Wild.” Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. 2018.