Analysis of Panoptic Image Segmentation Performance

Panoptic segmentation is a type of image segmentations that unifies instance and semantic segmentation. In this project we compare three different panoptic segmentations models: Panoptic FPN, MaskFormer, and Mask2Former. This includes descriptions of their architectures, objective analysis and subjective analysis of the models. We evaluated eaach modle on the COCO validation dataset with mmdetection, compared differences in model segmentation, and visualized the attentions of MaskFormer and Mask2Former with Detectron2 and HuggingFace.

- Introduction

- MMDetection Setup

- PanopticFPN with MMDetection

- Maskformer with MMDetection

- Mask2Former with MMDetection

- Evaluation

- Visualizing Activations

- Summary & Conclusion

- References

Spotlight Video

Introduction

In 2019, a team from Facebook AI Research (FAIR) published a paper that defined a new field of computer vision called Panoptic Image Segmentation that combines detections of stuff and things [1]. However, before we can understand what panoptic segmentation is, we must understand some background.

Fig 1. Example cat image [2].

Fig 1. Example cat image [2].

Stuff & Things

- Stuff

- amorphous and uncountable regions of similar texture or material such as grass, sky, road defined by simply assigning a class label to each pixel in an image [1]

- Things

- Items in an image that could possess more than 1 countable instance defined by detecting each object and delineating it with a bounding box or segmentation mask [1]

Although identifying stuff and things sound like similar problems, the deep learning models that perform the task vary substansially in datasets, details, and evaluation metrics[1]

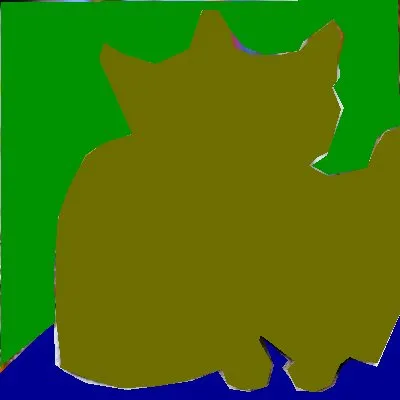

Semantic Segmentation

Semantic segmentation is a task that indentifies stuff. Semantic Segmentation is not concerned with individual objects, it instead identifies overall classes in an image. Each pixel is assigned a category label, creating blobs of each class.

Fig 2. Semantic Segmentation on the cat image [3].

Fig 2. Semantic Segmentation on the cat image [3].

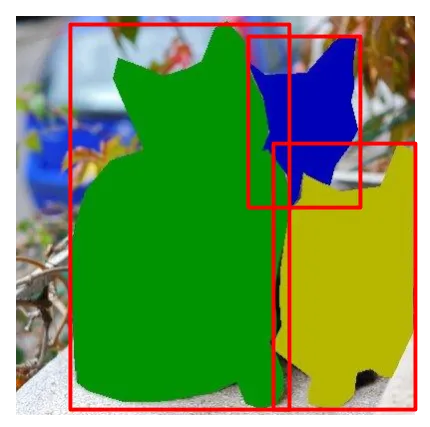

Instance Segmentation

Instance segmentation identifies things. It first identifies the objects, and then the pixels that belong to those things. This is done by first performing object detection and predicting a segmentation mask for the objects.

Fig 3. Instance Segmentation on the cat image [3].

Fig 3. Instance Segmentation on the cat image [3].

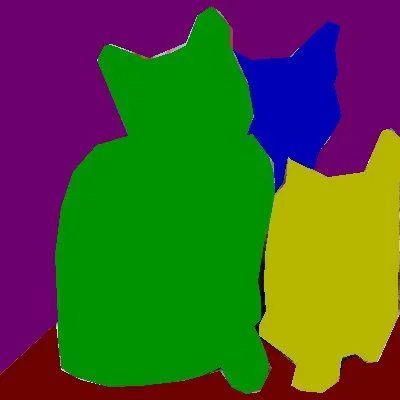

Panoptic Segmentation

The paper sets the groundwork for the panoptic image segmenation problem to reconcile the dichotomy between stuff and things by combining semantic and instance segmentation

Fig 4. Panoptic Segmentation on the cat image [3].

Fig 4. Panoptic Segmentation on the cat image [3].

Kirillov et al. defines a \(PS\) (Panoptic Score) and the requirements for a model to be considered a “panoptic segmentation model.” This task metric was designed because the standard metrics used for instance segmentation and semantic segmentation are best suited for stuff or things, respectively, but not both [1].

\[PS= \frac{ \sum_{ (p,g) \in TP} IoU(p,g) }{ |TP| + \frac{1}{2}|FP| + \frac{1}{2}|FN| }\]\(PS\) is composed of the count of three sets: true positives (\(TP\)), false positives (\(FP\)), and false negatives (\(FP\)), representing matched pairs of segments, unmatched predicted segments, and unmatched ground truth segments, respectively [1].

Intuitively, \(PS\) is the average intersection over union (\(IoU\)) of matched segments divided by a penalty for segments without matches: [1]

\[\frac{1}{2}|FP| + \frac{1}{2}|FN|\]Kirillov et al. defines the panoptic segmentation format algorithm to map each pixel to an semantic class and an optional instance class. In addition, there is a special instance label 0 that is used for a stuff class. Any segmentation mask with instance label 0 is considered a semantic segmentation mask

\[IoU(p_i,g)=\frac{|p_i\cap g|}{|p_i\cup g|}\]We will be evaluating and comparing multiple panoptic segmentation models on the COCO2017 dataset using MMDetection and attempt to use the results to evaluate the models panoptic quality [8, 9]. In addition, we will use Detection2 and Hugging Face to do individual image evaluation and to visualize attention from the pixel decoders of MaskFormer and Mask2Former [11, 10]

MMDetection Setup

We will be evaluating and modifying the panoptic segmentation models from the MMDetection ModelZoo using Google Colab for development. Therefore, we will need to install MMdetection and download the COCO-2017 dataset on our Google Drive for persistent storage of the dataset.

Install MMDetection in Google Colab

Luckily, a student group from the Winter2022 quarter of CS188 did most of the hard work with setting up MMDetection for Google Colab. They downloaded MMdetection and the COCO-2017 dataset to their Google Drive. MMDetecton Project

Unfortunately, we can’t just copy-and-paste the entire setup since there have been changes to the installation steps and versions in Pytorch, mmcv, and Pillow. In addition, we need to download the additional panoptic segmentation labels.

To begin, we create a new Colab notebook that we will (hopfully) run only once to install MMDetection and download the COCO-2017 dataset. In our case, we named it setup_mmdet_and_download_COCO.ipynb.

First, mount your drive, and install mmcv in our colab environment. There is no need to install a special version of Pytorch or Pillow in this version of Colab.

import os

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive', force_remount=True)

# install mmcv-full

!pip install mmcv-full==1.7.0 -f https://download.openmmlab.com/mmcv/dist/cu117/torch1.13/index.html

Make a directory in the drive called MMDet1 and clone the MMDetection github repository into it and install with pip.

!mkdir -pv /content/drive/MyDrive/MMDet1

%cd /content/drive/MyDrive/MMaDet1

# Install mmdetection

!rm -rf mmdetection

!git clone https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmdetection.git

%cd mmdetection

!pip install -e .

MMdetection is now downloaded on your Google Drive and installed in your Colab session. You should NEVER have to reclone the github repo in ANY colab notebook!

COCO-2017 Download

Now we will download the COCO-2017 dataset with the annotations for panoptic segmentation. First, make sure you are in the mmdetection folder in your drive, then use the download_dataset.py script to download the base COCO-2017 dataset. Then you will need to download the panoptic annotations. Next, unzip all the newly downloaded files into the data/coco directory.

The following code block will take about 5 hours to run fully. If you do not wish to wait all that time and would rather unzip in bursts, you can comment out all but the unzip command that your want to execute and run the cell for each unzip command. This allows you to unzip the files in chunks of time instead of all at once.

You will know that all files have been correctly extracted if when you run the code block again there are no outputs start with extracting.

Note:

1. You will need a GPU runtime to run thedownload_dataset.pypython script.

2. Sometimes the dataset will not fully unzip and not let you know. Make sure to rerun this block until there are not outputs of newly extracted filenames.

# suppose data/coco/ does not exist

!mkdir -pv data/coco/

# download the coco2017 dataset

!python3 tools/misc/download_dataset.py --dataset-name coco2017

# Adjust the dataset to include panoptic annotations

!wget -P data/coco/ http://images.cocodataset.org/annotations/image_info_test2017.zip

!wget -P data/coco/ http://images.cocodataset.org/annotations/panoptic_annotations_trainval2017.zip

# unzip them

!unzip -u "data/coco/annotations_trainval2017.zip" -d "data/coco/"

!unzip -u "data/coco/test2017.zip" -d "data/coco/"

!unzip -u "data/coco/train2017.zip" -d "data/coco/"

!unzip -u "data/coco/val2017.zip" -d "data/coco/"

!unzip -u data/coco/image_info_test2017.zip -d data/coco/

!unzip -u data/coco/panoptic_annotations_trainval2017.zip -d data/coco/

!unzip -u data/coco/annotations/panoptic_train2017.zip -d data/coco/annotations

!unzip -u data/coco/annotations/panoptic_val2017.zip -d data/coco/annotations

Finally, convert the standard COCO annotations to the panoptic annotations with the gen_coco_panoptic_test_info.py script.

!python tools/misc/gen_coco_panoptic_test_info.py data/coco/annotations

You are now ready to get started with working with MMDetection in Colab. Please make sure that you install mmcv, cocodataset/panopticapi, enter the mmdetection directory and run pip install -e . with each new document.

PanopticFPN with MMDetection

Background

The Panoptic FPN was designed as a single-network baseline for the panoptic segmentation task. They do this by starting from Mask R-CNN, a popular instance segmentation model, with a Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) backbone based on ResNet. They create a minimal semantic segmentation branch using the same features of the FPN to generate a dense-pixel output [3]. The author’s goal is to maintain top of the line performance for segementation quality (\(SQ\)) and recognition quality (\(RQ\)) [3].

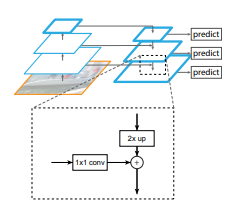

Fig 5. Feature Pyramid Network Diagram [4].

Fig 5. Feature Pyramid Network Diagram [4].

Feature Pyramid Network

The FPN consists of a botton up pathway and a top-down pathway. The bottom-up pathway consists of feature maps of several scales with a scaling step of 2. Each step corresponds to a residual block stage from Resnet \(\{C2, C3, C4, C5\}\). The output of each step is the output of the activation function of the residual block (except for \(C1\) since it is so large). The stages have strides \(\{4, 8, 16, 32\}\) in order to downsample the feature map.

The top-down pathway starts from the deepest layer of the network and progressively upsamples it while adding in transformed versions of higher-resolution features from the bottom-up pathway. The higher stages of the top-down pathway are at a smaller resolution, but semantically stronger. The purpose of the top-down pathway is to use this information to make a spatially fine and semantically stronger feature map of the input. Finally, the output of each stage of the top-down pathway is the final output of the FPN (labeled predict in Fig. 5).

Instance Segmentation Branch

Mask R-CNN is an extension on Faster R-CNN that adds an masking head branch to predict an binary mask for each bounding box prediction. Panoptic FPN uses the Mask R-CNN with the ResNet FPN as a backbone since it has been used as a foundation for all top entries in recent recognition challenges [3].

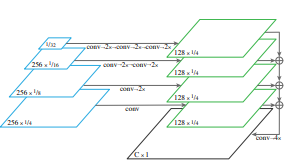

Semantic Segmentation Branch

The semantic segmentation branch also builds on the FPN in parallel with the instance segmentation branch. This semantic segmentation branch was designed to be as simple as possible and so it only upsamples each output of the FPN layers to 1/4th total size, add each together, and perform a 1x1 conv with a 4x bilinear upsampling. Each upsampling layer consists of a 3x3 convolution, group norm, ReLU, and 2x bilinear upsampling. It is important to note that in addition to each of the stuff class of the dataset, the branch can also output a ‘other’ class for pixels that do not belong to any classes. This avoids the branch predicting the pixels belong to no class as a incorrect class [1].

Fig 6. Instance Segmentation on the cat image [1].

Fig 6. Instance Segmentation on the cat image [1].

Setup

Before we do anything, let’s make sure we have our Colab environment set up correctly. Mount you Google Drive, install mmcv, cocodataset/panopticapi, and install the mmdetection library in your Colab session. Again, it is important to note that we do not re-clone the mmDetection github.

import os

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive', force_remount=True)

# Install mmcv-full

!pip install mmcv-full==1.7.0 -f https://download.openmmlab.com/mmcv/dist/cu117/torch1.13/index.html

# Install cocodataset/panopticapi

!pip install git+https://github.com/cocodataset/panopticapi.git

# Install mmdetection in colab environment

%cd /content/drive/MyDrive/MMDet1/mmdetection

!pip install -e .

Run Test Script

MMDetection pretrained PanopticFPN: Implementation Link

!CUDA_VISIBLE_DEVICES=0 python tools/test.py \

configs/panoptic_fpn/panoptic_fpn_r50_fpn_1x_coco.py \

checkpoints/panoptic_fpn/panoptic_fpn_r50_fpn_1x_coco.pth \

--work-dir /content/drive/MyDrive/MMDet1/mmdetection/results/panoptic1x \

--out outputs/panoptic_fpn_r50_fpn_1x_coco_out.pkl \

--eval PQ \

--eval-options jsonfile_prefix=/content/drive/MyDrive/MMDet1/mmdetection/results/panoptic1x

|

|

|

Fig 7. Example image and output from PanopticFPN. Top: test image, Left: output of PanopticFPN_1x, Right: output of PanopticFPN_3x [1].

Maskformer with MMDetection

Background

Semantic segmentation is often approached as per pixel classification, while instance segmentation is approached as mask classification. The key insight of Cheng, Schwing, and Kirillov to create the MaskFormer model is that “mask classification is sufficiently general to solve both semantic-level and instance-level segmentation tasks in a unified manner using the exact same model, loss, and training procedure.” [5] Mask classification can be used to solve semantic, instance, and panoptic segmentation together.

MaskFormer is a mask classification model which predicts a set of binary masks, each associated with one global class prediction [5]. MaskFormer converts a per-pixel classification model into a mask classification model [5].

Maskformer Architecture

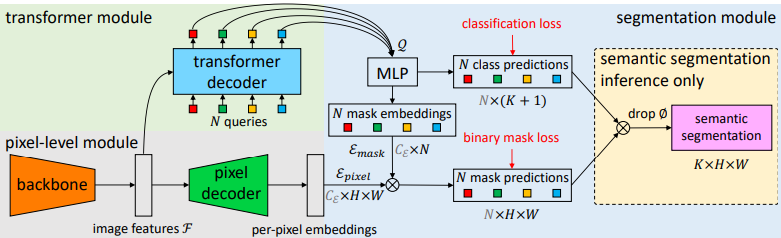

Fig 8. Maskformer Architecture [5]

Fig 8. Maskformer Architecture [5]

Maskformer breaks down into three modules: a pixel level module, a transformer module, and a segementation module. The pixel level module extracts per-pixel embeddings to generate the binary mask predictions, the transformer module computes per-segment embeddings, and the segmentation module generate the prediction pairs [5].

The pixel-level module begins with a backbone to extract features from the input image. The features are then upsampled by a pixel decoder into per-pixel embeddings. This module can be changed for any per-pixel classification-based segmentation model [5].

The transfomer module uses a a Transformer decoder to compute the per-segment embeddings from the extracted image features and learnable positional embeddings [5]. MaskFormer uses the standard Transfomer Decoder [7]

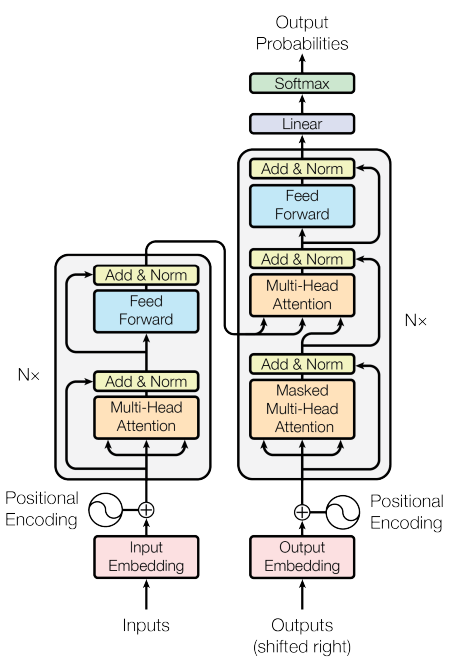

Fig 9. Transformer Decoder Architecture

Fig 9. Transformer Decoder Architecture

A Transformer is made up of an encoder (left) and a decoder stack (right). The encoder is made up of a stack of identical layers. The layers each begin with a multihead attention layer, followed by a fully connected feed forward layer. Each sublayer has a residual connection, which is then Layer Normalized. The decoder stack is similar to the encoder stack, but an additional multihead attention layer acts on the output of the encoder stack [7]. Finally a a linear layer and a softmax activation turn the attentions into output probabilities [7].

Attention is computed as:

\[Attention(Q,K,V)=softmax\left( \frac{ QK^T }{ \sqrt{d_k} } \right)V\]Q, K, and V are all vectors, where Q is a query, K is made up of keys, and V is made up of keys. The output is a weighted sum of the values, where the weight is computed by a compatability function between the query and the key [7]. In this case, the compatability function is softmax. This means that the most likely query-key combination’s value will have the highest weight, and thus the highest attention value. dk is the dimension of the keys and queries, and is used to scale the scale the QK product [5].

Multi-head attention takes the attention function on multiple different linearly projected versions of Q, K, and V in parallel [5]. These values are then cocatenated and projected again to get the final attention values [5].

The segmentation module uses a linear classifier followed by softmax on the per-segment embeddings to get the class probabilities of each segment. A 2 hidden layer Multi-Layer Perceptron gets the mask embeddings from the per-segment embeddings. To get the final binary mask predictions, the model takes a dot product between the ith mask embeddings and the per-pixel embeddings from the pixel-level module. This dot product is followed by a sigmoid activation to produce the output [5].

Setup

MaskFormer follows the same setup steps as Panoptic FPN to set up MMDetection.

Run Test Script

MMDetection pretrained MaskFormer: Implementation Link

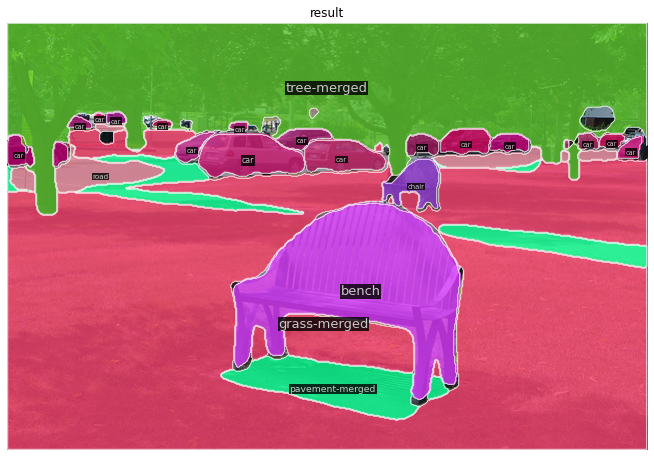

Fig 10. MaskFormer Sample Output

Fig 10. MaskFormer Sample Output

Mask2Former with MMDetection

Mask2Former Background

While MaskFormer is a universal architecture for semantic, instance, and panoptic segmentation, it is expensive to train and does not outperform specialized segmentation models [6]. Masked-attention Mask Transformer, or Mask2Former, is a universal segmentation method that outperforms specialized architectures, and is simpler to train on each task. Mask2Former is similar to MaskFormer, but with several improvements. The first is using masked attention in the Transformer decoder rather than cross-attention [6]. This restricts the attention on localized features centered around the predicted segments [6]. Second is using “multi-scale high-resolution features”, as well as optimization improvements and calculating mask loss on randomly sampled points to save training memory [6].

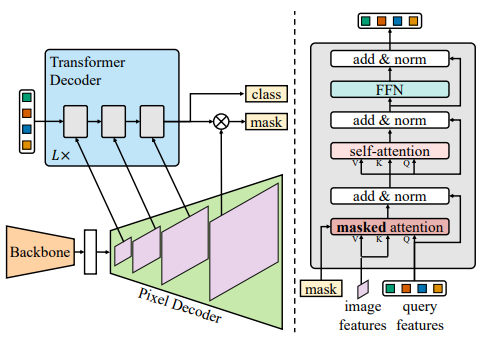

Mask2Former Architecture

Fig 11. Mask2Former Architecture [6]

Fig 11. Mask2Former Architecture [6]

Mask2Former follows the overall meta architecture from MaskFormer: a backbone to extract image features, a pixel decoder to upsample features into per-pixel embeddings, and a Transformer decoder to compute segments from the image features, but with the changes mentioned above [6].

Masked Attention

The first of these changes is using masked attention rather than cross attention in the Transformer decoder [6]. Masked attention is “a variant of cross-attention that only attends within the foreground region of the predicted mask for each query.” [6] This is achieved by adding an “attention mask” to standard cross attention. [6] Cross attention computes:

\[X_l=softmax(Q_lK_l^T)V_l+X_{l-1}\]Fig 12. Cross Attention Formula [6]

Masked attention modifies regular attention by adding an attention mask to the formula.

\[X_l=softmax(M_{l-1}+Q_lK_l^T)V_l+X_{l-1}\]Fig 13. Mask Attention Formula [6]

\[\begin{equation} M_{l-1}(x,y) = \biggl\{ \begin{array}{lr} 0, & \text{if } M_{l-1}(x,y)=1 \\ -\inf, & \text{otherwise} \end{array} \end{equation}\]Fig 14. Attention Mask at Feature (x,y) [6]

\(X_{l-1}\) represents a residual connection.

\(M_{l-1}\) is the mask prediction of the previous layer, converted to binary data with threshold 0.5. This is also resized to the same dimension as \(K_l\).

High-resolution Features

Higher-resolution features boost model performance, especially for small objects, but also increase computation cost [6]. To gain the benefit of higher resolution images while also limiting computation cost increases, Mask2Former uses a feature pyramid of both high and low resolution features produced by the pixel decoder with resolutions 1/32, 1/16, and 1/8 of the original image [6]. Each of these different feature resolutions are fed to one layer of the Transformer decoder, as can be seen in the Mask2Former architecture image. This is repeated L times in the decoder, for a total of 3L layers in the Transformer decoder [6].

Optimization Improvements

Mask2Former makes three changes to the standard Transformer decoder design [6]. The first is that Mask2Former changes the order of the self-attention and cross-attention layers (mask-attention layer), starting with the mask-attention layer rather than the self-attention layer [6]. Next the query features (\(X_0\)) are made learnable, which are supervised before being used to compute masks (\(M_0\)) [6]. Lastly dropout is removed, as it was not found to help performance [6].

Finally to improve training efficienty, Mask2Former calculates the mask loss with samples of points rather than the whole image [6]. In matching loss, a set of K points is uniformly sampled for all the ground truth and prediction masks [6]. In the final loss, different sets of \(K\) points are sampled with importance sampling for each pair of predictions and ground truth [6]. This sampled loss calculation reduces required memory during training by 3x [6].

Setup

Mask2Former follows the same setup steps as Panoptic FPN to set up MMDetection.

Run Test Script

MMDetection pretrained Mask2Former: Implementation Link

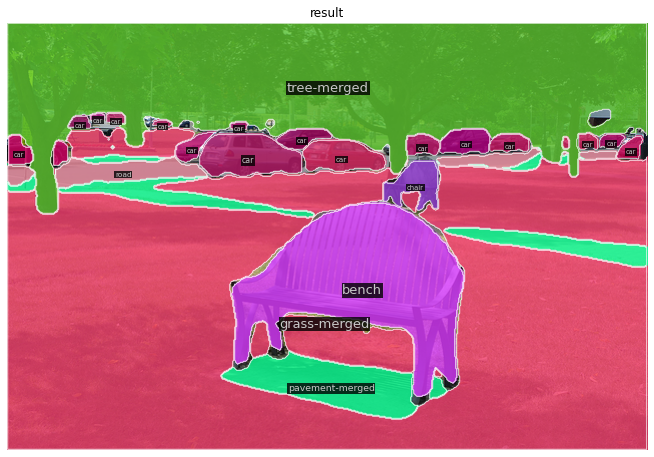

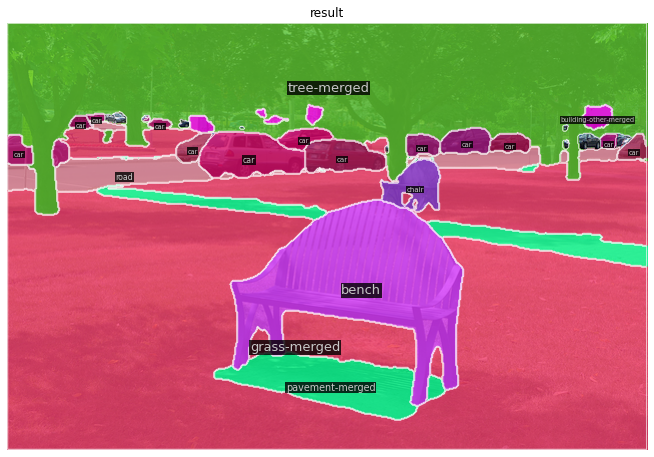

Fig 15. Mask2Former Sample Output

Fig 15. Mask2Former Sample Output

Evaluation

Here are the results from evaluating the models on the Coco validation set with mmdetection.

| Model | Targets | PQ | SQ | RQ | Categories | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panoptic 1x ResNet50 Coco | All | 40.248 | 77.785 | 49.312 | 133 | ||

| Things | 47.752 | 80.925 | 57.475 | 80 | |||

| Stuff | 28.922 | 73.046 | 36.991 | 53 | |||

| Panoptic 3x ResNet50 Coco | All | 42.457 | 78.118 | 51.705 | 133 | ||

| Things | 50.283 | 81.478 | 60.285 | 80 | |||

| Stuff | 30.645 | 73.046 | 38.755 | 53 | |||

| MaskFormer Resnet50 | All | 46.854 | 80.617 | 57.085 | 133 | ||

| Things | 51.089 | 81.511 | 61.853 | 80 | |||

| Stuff | 40.463 | 79.269 | 49.888 | 53 | |||

| Mask2Former Resnet50 | All | 51.865 | 83.071 | 61.591 | 133 | ||

| Things | 57.737 | 84.043 | 68.129 | 80 | |||

| Stuff | 43.003 | 81.604 | 51.722 | 53 |

Across the evaluations, the Panoptic FPN model had the lowest Panoptic Quality score with a score of 40.248 and 42.457 on the All category. MaskFormer had a score of 46.854, and Mask2Former scored 51.089. This was expected as MaskFormer is a later model than Panoptic FPN, and Mask2Former is an improved version of MaskFormer. However, an increase of 9.408 between the larger Panoptic FPN and Mask2Former still shows significant improvement from Panoptic FPN to Mask2Former.

|

|

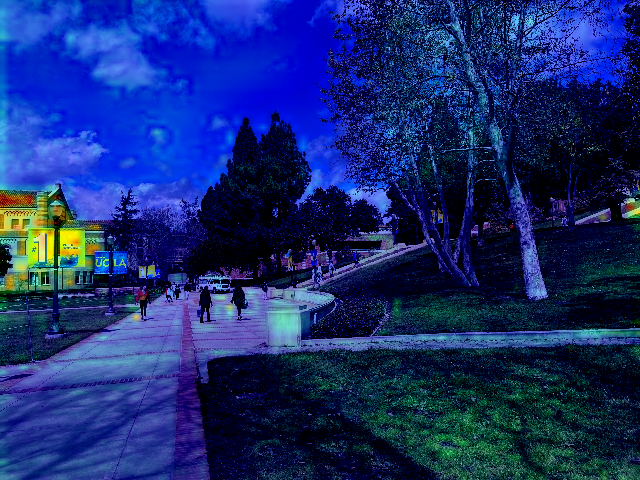

Fig 16. Plane Image from COCO and Janns Image we took ourselves

|

|

For testing the outputs of the models we used these two images. The plane is from the COCO validation set [8] while the image of Janns we took ourselves.

|

|

|

Fig 17. (Left to Right) Panoptic FPN, MaskFormer, Mask2Former Results on Plane Image

Looking at the segmentation outputs, Panoptic FPN does not appear to segment the image as well as MaskFormer and Mask2Former. Especially on the tail of the airplane, Panoptic FPN has a squigly border that MaskFormer and Mask2Former don’t have. MaskFormer and Mask2Former are more similar, but Mask2Former does appear to have cleaner lines that better follow the lines of the objects.

|

|

|

Fig 18. Panoptic FPN, MaskFormer and Mask2Former Result on Bruinwalk Image

The segmentations by the three models are more different than with the plane. Panoptic FPN has classified a patch of the road in the foreground differently than the other 2, and MaskFormer classified the wall as a bench unlike the other two. This image has more detail in it than the plane image, with more objects and smaller details, which could account for these model differences. This is also not a COCO image, and thus could be a bit more removed from the data that the models were trained on.

Model Segmentation Comparisons Impementation Link

We took the outputs of the different models to compare the differences in their segmentations on the two images. We checked the outputs masks and marked where the models classified pixels in the images differently.

|

|

Fig 19. Panoptic FPN and MaskFormer Output Difference

As mentioned earlier, the models had different classifications around the border of the airplane, especially the tail, which is highlighted by the red difference overlays. We can also see the greater differences between the segmentations on the Janns image by the larger red areas.

|

|

Fig 20. Panoptic FPN and Mask2Former Output Differnce

Panoptic FPN and Mask2Former show similar differences as Panoptic FPN and MaskFormer. MaskFormer and Mask2Former had appeared to make more similar segmentations on the image, so it makes sense that Mask2Former would have similar differences with PanopticFPN.

Fig 21. MaskFormer and Mask2Former Output Difference

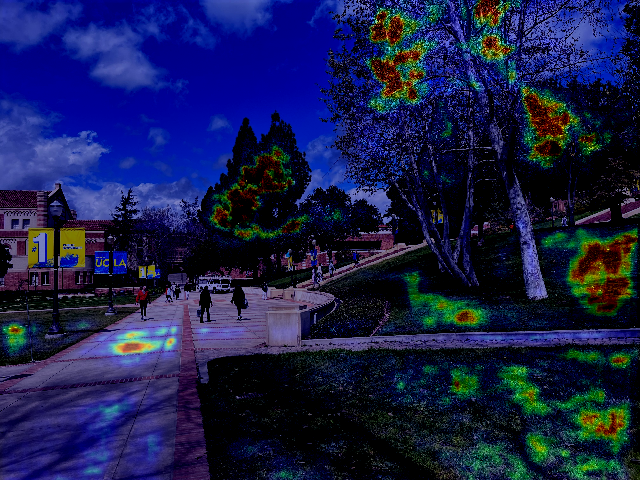

Visualizing Activations

In addition to evaluting the model in a traditional sense with the \(PQ\), \(SQ\), and \(RQ\), we also did a qualitative analysis of the pixel decoder output’s activations. To easily work with the internal logits we decided to install Hugging Face with:

!pip install -q git+https://github.com/huggingface/transformers.git

In this google colab implementation, we develop the get_attention method that uses the pixel_decoder_last_hidden_state tensor that is part of the output of the hugging faces pretrained model. This tensor corresponds to the hidden output from the pixel decoder modules for Maskformer and Mask2former. We then take the feature mask that is most activated from the pixel decoder and do some interpolate the data to [0,255] before applying the features as a heatmap to the original image.

The results for MaskFormer and Mask2Former are below.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig 22. MaskFormer and Mask2Former Attention for the 3 test images: Janns steps, Cat, and Plane from top-down

We can see that Mask2Former’s pixel decoder extracts more semantic information in its pixel decoder. This means that the Swin Transformer backbone was likely able to extract more important information than MaskFormer’s backbone. We can see that the maximally activated feature mask for the Janns picture is very clearly focused on the building in the backgound. On the other hand, MaskFormer is more focused on the trees in the foreground and background. The cat image seems to also be very accurate for Mask2Former compared to the results from MaskFormer. Both of their maximally activated features are focused on the cats, but it is interesting to see that they focus on different cats. Finally, Mask2Former’s maximally activated feature mask is able to accurately focus on the plane in the center of the frame while MaskFormer’s pixel decoder output seems confused and is focused on both the plane and the sky.

Summary & Conclusion

Panoptic segmentation models unify instance and semantic segmentation. MaskFormer uses mask classification to perform panoptic segmentation, instead of just instance segmentation. Mask2Former improves upon MaskFormer by changing the attention of the model’s Transformer from ordinary cross attention to their own “masked attention” [6].

Assessing the results of the different models, Mask2Former performs the best, both quantatively by the panoptic quality score, as well as qualitatively by assessing the model segmentations on different images.

References

[1] Alexander Kirillov, Kaiming He, Ross Girshick, Carsten Rother, and Piotr Dollár. “Panoptic Segmentation”. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).2019.

[2] Mechea, Daniel. “What Is Panoptic Segmentation and Why You Should Care.” Medium. Medium, January 29, 2019. https://medium.com/@danielmechea/what-is-panoptic-segmentation-and-why-you-should-care-7f6c953d2a6a.

[3] Alexander Kirillov, Ross Girshick, Kaiming He, and Piotr Dollár. “Panoptic Feature Pyramid Networks.” (2019).

[4] Tsung-Yi Lin, Piotr Dollár, Ross Girshick, Kaiming He, Bharath Hariharan, and Serge Belongie. “Feature Pyramid Networks for Object Detection.” (2017).

[5] Bowen Cheng, Ishan Misra, Alexander G. Schwing, Alexander Kirillov, and Rohit Girdhar. “Masked-attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation.” (2022).

[6] Bowen Cheng, Alexander G. Schwing, and Alexander Kirillov. “Per-Pixel Classification is Not All You Need for Semantic Segmentation.” (2021).

[7] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N. Gomez, Lukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. “Attention Is All You Need.” (2017).

[8] Tsung-Yi Lin, Michael Maire, Serge J. Belongie, Lubomir D. Bourdev, Ross B. Girshick, James Hays, Pietro Perona, Deva Ramanan, Piotr Dollár, and C. Lawrence Zitnick. “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context”.CoRR abs/1405.0312 (2014).

[9] Chen, Kai, Jiaqi, Wang, Jiangmiao, Pang, Yuhang, Cao, Yu, Xiong, Xiaoxiao, Li, Shuyang, Sun, Wansen, Feng, Ziwei, Liu, Jiarui, Xu, Zheng, Zhang, Dazhi, Cheng, Chenchen, Zhu, Tianheng, Cheng, Qijie, Zhao, Buyu, Li, Xin, Lu, Rui, Zhu, Yue, Wu, Jifeng, Dai, Jingdong, Wang, Jianping, Shi, Wanli, Ouyang, Chen Change, Loy, and Dahua, Lin. “MMDetection: Open MMLab Detection Toolbox and Benchmark”.arXiv preprint arXiv:1906.07155 (2019).

[10] Thomas Wolf, , Lysandre Debut, Victor Sanh, Julien Chaumond, Clement Delangue, Anthony Moi, Pierric Cistac, Tim Rault, Rémi Louf, Morgan Funtowicz, Joe Davison, Sam Shleifer, Patrick von Platen, Clara Ma, Yacine Jernite, Julien Plu, Canwen Xu, Teven Le Scao, Sylvain Gugger, Mariama Drame, Quentin Lhoest, and Alexander M. Rush. “Transformers: State-of-the-Art Natural Language Processing.” . In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing: System Demonstrations (pp. 38–45). Association for Computational Linguistics, 2020.

[11] Yuxin Wu, , Alexander Kirillov, Francisco Massa, Wan-Yen Lo, and Ross Girshick. “Detectron2.” (2019).