A Deep Dive Comparison of 3D Object Detection Methodologies

This report delves into the realm of 3D object detection that is a large topic in the realm in computer vision. The demand for sophisticated perception systems is especially relevant in the recent developments in autonomous vehicles, robotics, and augmented reality. The ability to detect and localize objects in a three-dimensional space has become increasingly important due to the high precision and accuracy that these methods require, especially in the case of autonomous vehicles where lives are at stake. This report provides an overview of 3D object detection, explaining the many different methods in depth to achieve accurate detection. We go over three vastly different approaches - point based methods, voxel-based methods, and transformer based methods - aiming to explain and compare the performance, strength and weaknesses, and architecture of each.

- Introduction

- Methods for 3D Object Detection

- Performance Analysis on Different Methods

- Conclusion

- Reference

Introduction

3D object detection borrows lots of the existing methods and knowledge from traditional 2D object detection, and also differs in some ways. This section aims to provide fundamental knowledge in deep learning and 3D object detection along with basic architecture that were inspired from 2D object detection and others that have been created to solve 3D object detection.

Some Parallels and Differences in 2D and 3D object detection

One striking difference between the two methodologies is of course the input and output space. While 2D object detection relies on color and two dimensional positioning, 3D object detection relies mainly on three dimensional data in the form of voxels or point clouds, where something like a classification network that relies heavily on the linearization of data would be exponentially less effective in a 3D deep learning implementation.

While 2D object detection has popularized single-shot object detection techniques like YOLO, popular 3D object detection usually requires multiple stages of object detection although single-shot 3D object detection is still being actively researched. PointRCNN is a very clear example of this as a two-stage process in its use of PointNet as feature extraction in conjunction with an RPN (Region Proposal Network) and a bounding box refinement process in the second stage in the form of pooling and classification.

Classic Inputs for 3D Object Detection Models

The most popular type of input for 3D object detection models are point clouds which hold an X, Y, and Z value in a three dimensional array, with an additional encoding of RGB colors, intensity values, etc. if needed. Point clouds are created from technologies like LiDAR which extract point clouds using positional data derived from the light reflection from an initial laser light.

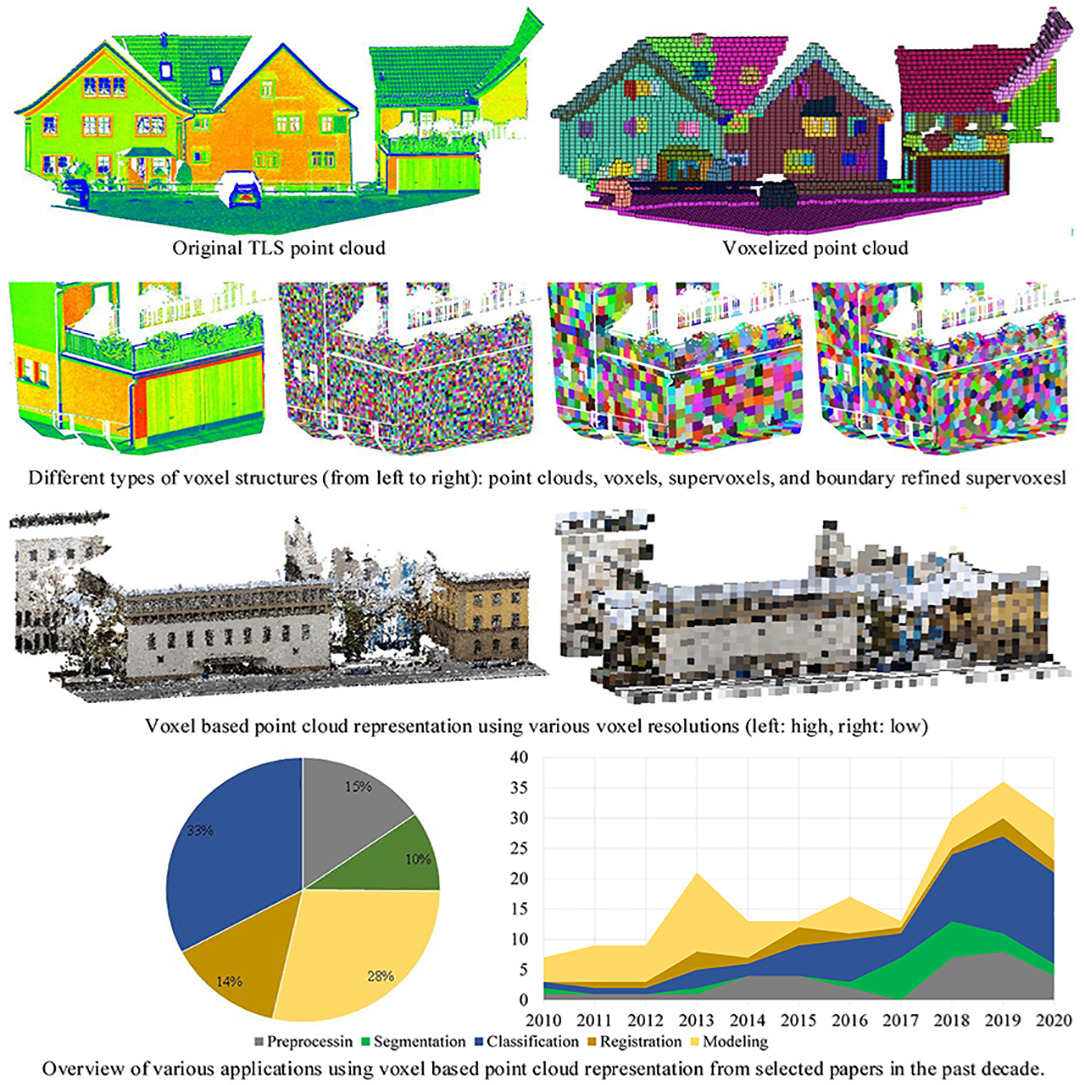

Oftentimes, these point clouds are further processed into two-dimensional voxels which make processing easier as compared to a PointNet and further RPN in the later layers of the model. Voxel based inputs create regular grid structures and consistent representations to streamline the processing of the information. Voxelization offers drawbacks, often not being used for high precision tasks like autonomous drawbacks because of its approximations and loss of fine-grained features that come with a voxel grid.

3D object detection also may utilize 2D image inputs by way of projecting a point cloud onto 2D images to leverage multiple points of view for a relatively accurate 3D imaging and further process the data. Other methods that process 2D images include frustum utilized in NeRF which convert two-dimensional images into three-dimensional space.

Yet another type of data collection is other fusion-based approaches which utilize mainly cameras and lidars to most accurately depict the environment. Most robust solutions of autonomous driving derives its three-dimensional data from this fusion-based approach.

Fig 1. Point Cloud vs Voxel Grid Representation of a 3D Object [1].

Evaluation Metrics for 3D Object Detection

One metric often used for evaluating 3D object detection models is 3D IoU. IoU stands for Intersection over Union, which calculates the overlap between predicted and ground truth bounding boxes, considering both the position and size of the bounding box.

Another metric is AP or Average Precision. This provides a single-figure measure of the model’s accuracy across various thresholds of detection confidence at different recall rates. It offers a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s detection performance, factoring in both the precision (how many detections were correct) and the recall (how many actual objects were detected).

One last metric that is fundamental to evaluating 3D object detection is recall rates, which assesses the model’s ability to detect all relevant instances in the dataset, which is critical for applications where missing an object can have serious consequences, like in autonomous driving or security.

Methods for 3D Object Detection

There are several approaches for 3D object detection that have been well-tested and widely accepted, however, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. Below, we discuss these methods, their loss functions, and their strengths and weaknesses; classifying them as point-based, voxel-based, and transformer-based methods.

Point-based Methods

Point-based methods directly operate on 3D point clouds to perform object detection in a three-dimensional space. Point clouds are sets of points in 3D space, often obtained from sensors such as LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) or depth cameras. In the following sections, we will cover the architecture and loss functions of a prominent point-based method: PointRCNN.

PointRCNN

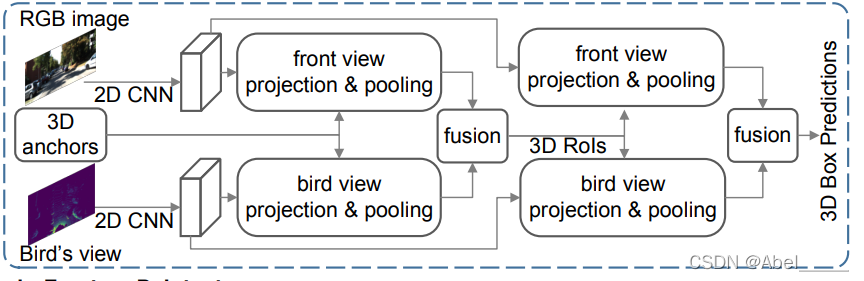

Fig 2. The first stage of PointRCNN [3].

PointRCNN was introduced by Shaoshuai Shi, Xiaogang Wang, and Hongsheng Li at The Chinese University of Hong Kong in their 2019 research paper (Shi, Shaoshuai, et al., 2019). In their research, they introduced PointRCNN, a novel method for 3D object detection that directly uses raw point cloud data.

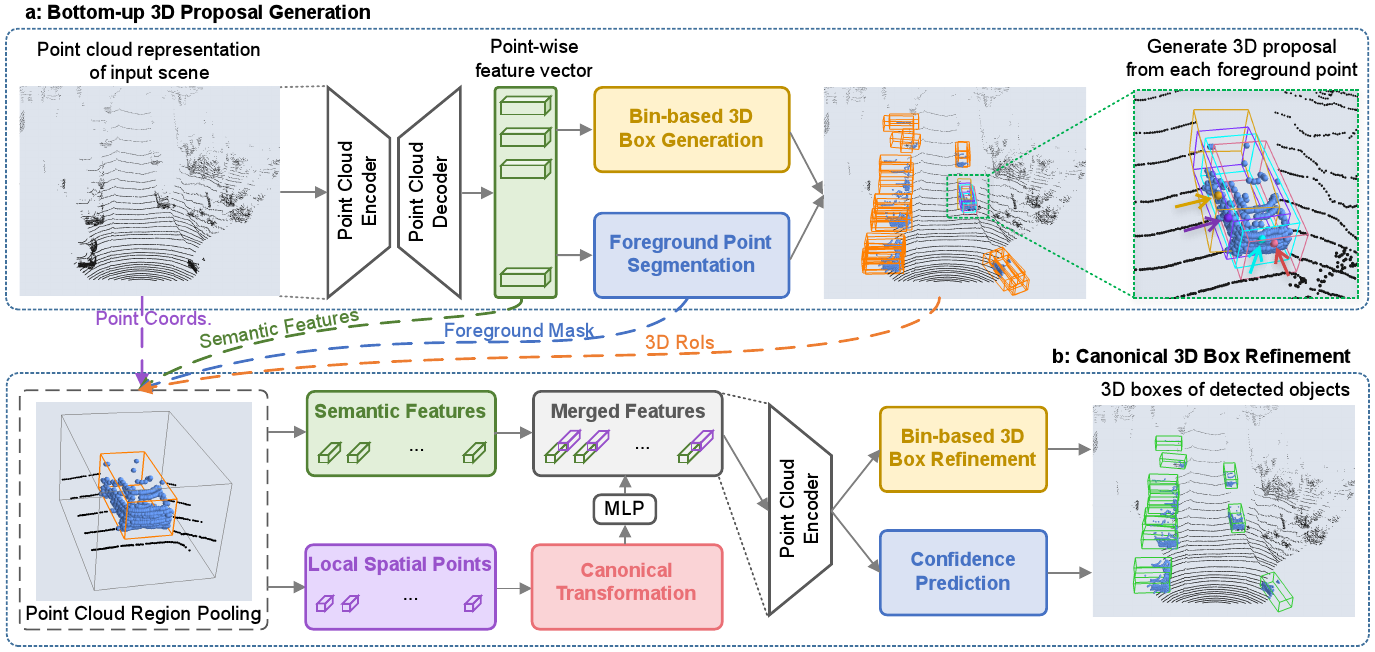

Fig 3. The second stage of PointRCNN [3].

Their proposed framework consisted of two distinct stages: the first stage focuses on generating 3D proposals in a bottom-up manner, while the second stage refined these proposals in canonical coordinates to achieve precise detection results. Unlike previous methods that relied on generating proposals from RGB images or projecting point clouds to bird’s eye view or voxels, their stage-1 sub-network directly segments the entire point cloud of the scene into foreground and background points, generating a small number of high-quality 3D proposals. Their stage-2 sub-network then transforms the pooled points of each proposal into canonical coordinates to extract better local spatial features. These features, combined with the global semantic features learned in stage-1, enables accurate refinement of bounding boxes and confident prediction of objects.

Advantages and Limitations

Point-based methods excel in preserving fine-grained geometric details found in point clouds, enabling precise object localization and recognition. There is no need for voxelization, unlike voxel-based methods that we will describe in the following sections. However, point-based methods might incur high computational loads as each point has to be computed independently.

Loss

In refining box proposals generated by the PointRCNN model, a ground-truth box is assigned to a 3D box proposal for refinement learning if their 3D Intersection over Union (IoU) exceeds 0.55, and both the 3D proposals and their corresponding ground-truth boxes are transformed into canonical coordinate systems. The training targets for the center location of the box proposal are determined based on Eq. (2), with a smaller search range for refining proposal locations. Size residuals are directly regressed with respect to the average object size of each class, as the sparse points may not provide sufficient size information.

\[\begin{aligned} & \operatorname{bin}_x^{(p)}=\left\lfloor\frac{x^p-x^{(p)}+\mathcal{S}}{\delta}\right\rfloor, \operatorname{bin}_z^{(p)}=\left\lfloor\frac{z^p-z^{(p)}+\mathcal{S}}{\delta}\right\rfloor, \\ & \operatorname{res}_u^{(p)}=\frac{1}{\mathcal{C}}\left(u^p-u^{(p)}+\mathcal{S}-\left(\operatorname{bin}_u^{(p)} \cdot \delta+\frac{\delta}{2}\right)\right), \\ & u \in\{x, z\} \\ & \operatorname{res}_y^{(p)}=y^p-y^{(p)} \end{aligned}\]Overall, the loss function for the stage-2 sub-network involves various components for refining box proposals, encompassing center location, size, and orientation refinement. Described by this equation:

\[\begin{aligned} \mathcal{L}_{\text {refine }}= & \frac{1}{\|\mathcal{B}\|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{B}} \mathcal{F}_{\text {cls }}\left(\operatorname{prob}_i, \text { label }_i\right) \\ & +\frac{1}{\left\|\mathcal{B}_{\text {pos }}\right\|} \sum_{i \in \mathcal{B}_{\text {pos }}}\left(\tilde{\mathcal{L}}_{\text {bin }}^{(i)}+\tilde{\mathcal{L}}_{\text {res }}^{(i)}\right) \end{aligned}\]Voxel-based Methods

Voxel-based methods offer a structured approach to analyzing dense 3D point cloud data by discretizing space into small volumetric units called voxels. By preserving spatial relationships and geometric properties, these methods facilitate the application of deep learning techniques for tasks such as object detection, scene understanding, and medical imaging. Widely used in domains like autonomous driving and robotics, voxel-based methods hold promise for advancing 3D perception and scene analysis in real-world environments. This introduction provides a glimpse into the principles and applications of voxel-based methods in 3D object detection and beyond.

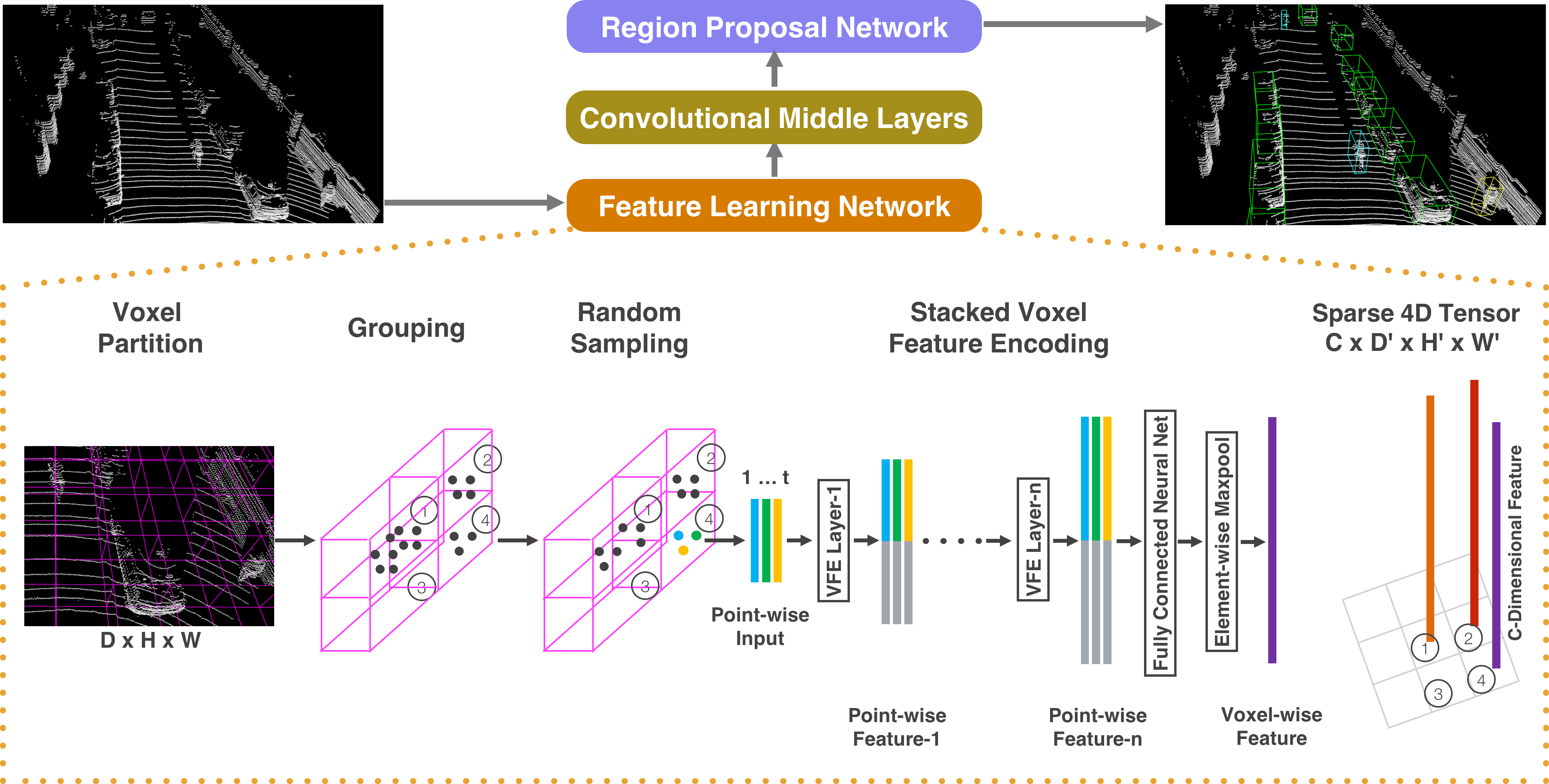

VoxelNet

The VoxelNet architecture was first introduced at the end of 2017, making an innovative methodology for processing the point cloud data. In an article published by Yin Zhou and Oncel Tuzel, both from Apple Inc, expresses the use of a highly sparse LiDAR point cloud with a region proposal network, removing the existing efforts of bird’s eye view projection. In this figure above, it diagrams the VoxelNet architecture.

Fig 4. An overview of VoxelNet’s Architecture [4].

Given a raw point cloud as input, the feature learning network will partition the space into voxels, transforming points within the voxels into a vector representation. This is then represented as a sparse 4D tensor. This phase of the architecture is called voxelization. Following, the model divides the vehicles into small volumetric units called voxels. Here, it structures this point cloud data into a grid format so that it can be better processed by deep learning models.

In the following process, the convolutional middle layers then process this 4D tensor to combine spatial data. In this layer, it begins to extract pertinent features from the previous voxelized input. Using the VoxelNet method, we will encode local geometric and spatial characteristics, using metrics such as occupancy, density, and intensity. These are computed by aggregating information from each voxel. Using multiple layers of 3D convolutions, pooling operations, and activation functions, it will work in tandem to learn the voxel feature’s representations, utilizing local and global spatial relationships between features of the entire grid. Based on previous knowledge of regional proposed networks from Faster R-CNN, it behaves in a similar fashion. The RPN operates on learned voxel features to propose potential object locations with anchor boxes that are refined to a tight bounding box.

Advantages and Limitations

Voxel-based methods offer structured and uniform representations of 3D scenes, simplifying feature learning with 3D CNNs. They ensure an effective transformation of the raw input point cloud data into structured grid representation, which enables for better processing and accurate detection and localization of the objects. However, voxelization increases memory and computational demands, especially with high-resolution grids or dense point clouds. However, this can be countered by storing a limited number of voxels so that we are able to further improve memory and computational efficiency. We may be able to ignore points coming from voxels with few points. Additionally, voxel representations may lack fine-grained geometric detail due to grid resolution limits. Nonetheless, voxel-based methods excel in 3D object detection benchmarks and remain pivotal in research efforts.

Transformer-based Methods

Transformer-based methods, renowned for their efficacy in natural language processing and computer vision, utilize self-attention mechanisms to grasp intricate data relationships. In 3D object detection, they directly process point cloud data, showing potential for superior performance. This section elucidates transformer-based techniques, including their components, algorithms, and benefits.

3DETR

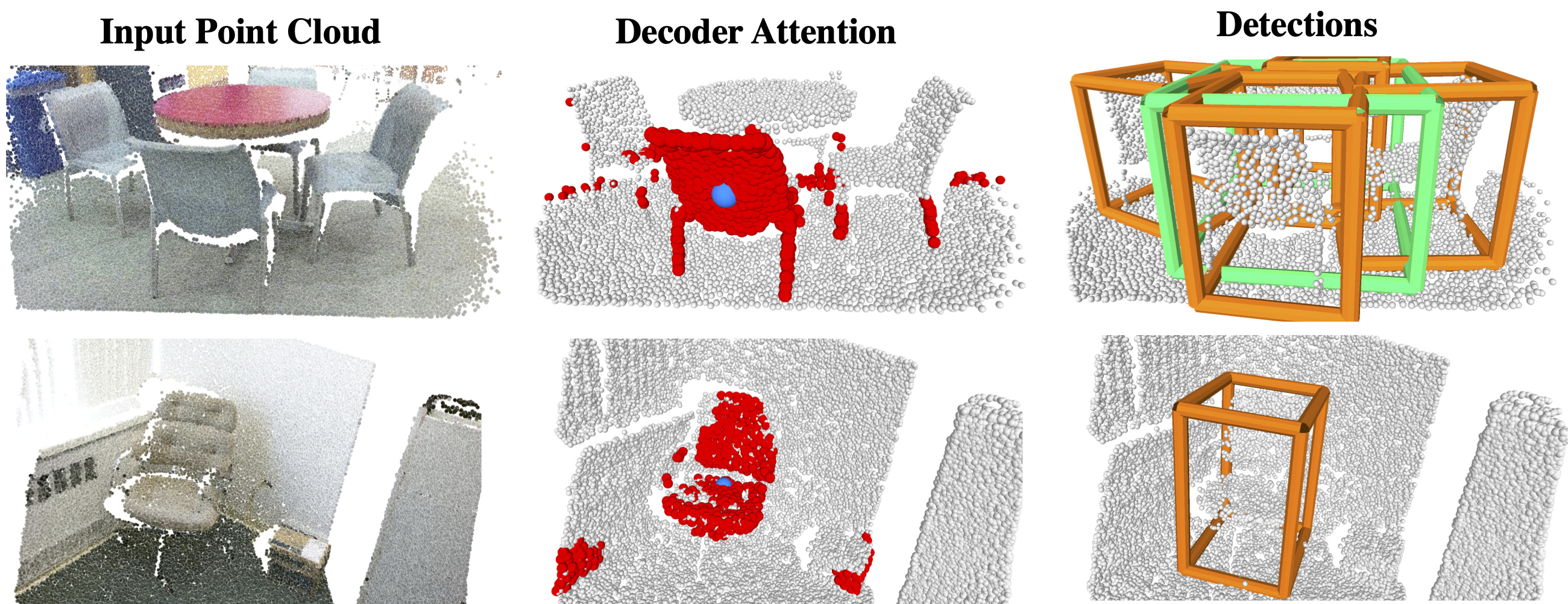

3DETR, which stands for 3D End-to-End Transformer, is a novel deep learning architecture designed specifically for 3D object detection tasks. Unlike conventional approaches that heavily rely on 3D convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and voxel-based representations, 3DETR leverages the Transformer model, originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), to process 3D point clouds directly. This innovative use of the Transformer model enables 3DETR to capture complex spatial relationships and dependencies within the data, leading to improved performance in 3D object detection.

There are three main components that make up 3DETR. First the Input Embedding Layer, is responsible for converting the raw 3D point cloud data into a high-dimensional feature space that can be processed by the Transformer model. Each point in the cloud is represented by its coordinates (x, y, z) and potentially additional features such as color or intensity. These features are then linearly transformed to a higher-dimensional space. Next, the Transformer Encoder, the core of 3DETR, is a standard Transformer encoder that consists of multiple layers of self-attention and feedforward neural networks. The self-attention mechanism allows the model to weigh the importance of different points in the point cloud relative to each other, capturing the global context of the scene. The encoder processes the embedded input sequence and outputs a sequence of feature representations with the same length. Lastly, the output of the Transformer encoder is passed to the prediction heads, which are typically fully connected layers. There are usually two prediction heads: one for bounding box regression, which predicts the size and location of the bounding boxes around the detected objects, and another for class prediction, which assigns a class label to each detected object.

Fig 5. 3DETR example [5].

Differences

Some obvious differences between the methods is that 3DETR processes 3D point clouds directly. Because of this, It does not rely on intermediate representations but instead utilizes the unstructured data of point clouds. This direct approach preserves the fidelity of the spatial information contained within the data. On the other hand, VoxelNet, converts the point cloud into a structured 3D voxel grid. 3DETR offers a more direct and global processing method via the Transformer model, and VoxelNet provides a structured, hierarchical approach through voxelization and convolutional networks.

Advantages and Limitations

Transformer-based methods excel in capturing long-range dependencies in point clouds, enabling effective handling of spatial interactions and varied object layouts. They’re adaptable to sparse and irregularly sampled data. They are efficient by using parallelization and scalability. However, their computational demands are high due to numerous parameters as they are incredibly data-hungry during pre-training and the complexity of self-attention mechanisms. Because of this, we require heavy computational resources to support transformer-based methods. Additionally, sensitivity to noise and outliers greatly affect the training as well, having a lack of interpretability. The complex interactions between tokens of self-attention causes some uncertainty of how the model makes its predictions.

Loss

\[\begin{aligned} L & =\alpha \frac{1}{N_{\mathrm{pos}}} \sum_i L_{\mathrm{cls}}\left(p_i^{\mathrm{pos}}, 1\right)+\beta \frac{1}{N_{\mathrm{neg}}} \sum_j L_{\mathrm{cls}}\left(p_j^{\mathrm{neg}}, 0\right) \\ & +\frac{1}{N_{\mathrm{poss}}} \sum_i L_{\mathrm{reg}}\left(\mathbf{u}_i, \mathbf{u}_i^*\right) \end{aligned}\]Performance Analysis on Different Methods

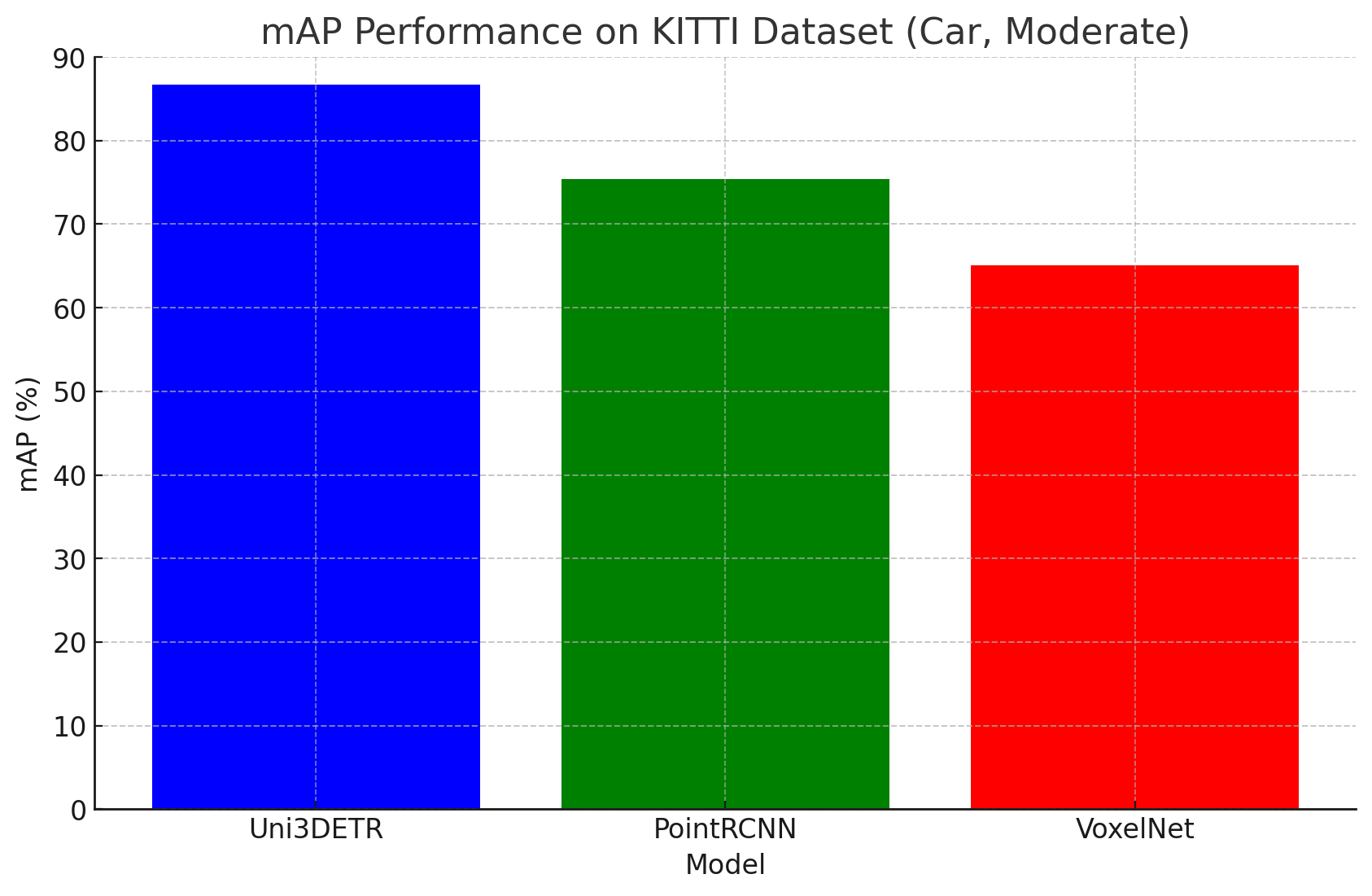

After evaluating the specifics of each model, we decided to evaluate each model on a unified dataset, KITTI (Car, Moderate) from the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology and Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago. The KITTI Cars, Moderate dataset states its validation being Min. bounding box height: 25 Px, Max. occlusion level: Partly occluded, Max. truncation: 30 %.

We evaluated three models on an Average Precision calculation

\[AP = \sum_{n} (R_{n} - R_{n-1}) \times P_{interp}(R_{n})\]Where \(AP\) is the average precision , \(P_{interp}\) is the is the interpolated precision at the $n$th recall level, which is the maximum precision found at any recall level greater than or equal to \(R_n\), and \(R_n\) represents the recall at the \(n\)th threshold.

The three pre trained models that we evaluated are the PointRCNN model, utilizing point based methods, VoxelNet, utilizing voxel based methods, and Uni3DETR, utilizing end to end transformer based methods, derived from 3DETR, all open-sourced.

Data and Validation Set Installation

Each model more or less followed this method of data instantiation, where the KITTI dataset was downloaded into the data portion of the code. The models called for velodyne point clouds, which are a specific type of point cloud generated from Velodyne HDL, a network-based 3D LiDAR system that produces 360 degree point clouds containing over 700,000 points every second. One would also need the labeled data to compare the Average Precision.

(Model)

├── data

│ ├── KITTI

│ │ ├── ImageSets

│ │ ├── object

│ │ │ ├──training

│ │ │ ├──calib & velodyne & label_2 & image_2 & (optional: planes)

│ │ │ ├──testing

│ │ │ ├──calib & velodyne & image_2

├── tools

Model Validation

After installation, each model needs to be validated with the KITTI Dataset. We evaluated the predictions from the model to the ground truths dataset using mAP (mean Average Precision). The function below describes a basic overview of the code we used to evaluate each model using sklearn.metrics.

def calculate_map(predictions, ground_truths, iou_threshold):

"""

Calculate the mean Average Precision (mAP) for a given IoU threshold.

:param predictions: List of prediction tuples (confidence_score, iou_score)

:param ground_truths: List of ground truth IoU scores

:param iou_threshold: IoU threshold to consider a detection as positive

:return: mAP value

"""

# Extract confidence scores and sort predictions by them in descending order

confidences, ious = zip(*sorted(predictions, key=lambda x: x[0], reverse=True))

# Convert IoU scores to binary list indicating whether prediction is true positive

true_positive_flags = [iou >= iou_threshold for iou in ious]

# Calculate precision and recall at each threshold

precision, recall, _ = precision_recall_curve(true_positive_flags, confidences)

# Compute the area under the precision-recall curve (AUC) as AP

ap = auc(recall, precision)

return ap

The mean average precision was calculated and the results are shown below:

Fig #. mAP values for object detection models.

Although this is an extremely naive way of evaluating each model, one could extrapolate the importance of feature extraction from each, where an apparent result was VoxelNet’s voxel conversion structure led to poor performance due to its limitations on feature representation using such abstracted data. However, VoxelNet’s speed could compensate hypothetically in a further application of AR and robotics.

Conclusion

In conclusion, 3D object detection plays a pivotal role in enabling machines to perceive and interact with the world in three dimensions. Technologies such as LiDAR and other multi-view based methods including NeRF and frustum have made 3D object detection extremely precise and accurate to the point of autonomous driving being viable. Various methodologies, including point-based, voxel-based, and fusion-based approaches, have been developed to tackle this challenging task. Point-based methodologies were further abstracted to the PointRCNN model, describing each layer and its functionalities, where its usage of an RPN and Rol-Pooling were explained. Voxel-based methodologies were described using the VoxelNet model, utilizing voxels in order to create faster approximations using the power of voxels. Transformer-based methodologies were explained alongside the architecture of 3DETR, contextualizing the use of attention and transformers in the space of 3D object detection. Each method has its advantages and is suited to different application scenarios based on factors such as sensor availability, computational efficiency, and environmental conditions. We then evaluated the models solely on a dataset seeking to classify cars for autonomous driving and found that Uni3DETR performed outstandingly while data abstractions in voxel-based methodologies proved lacking in this specific application. Moving forward, continued research and innovation in 3D object detection will be essential for advancing the capabilities of autonomous systems and robotics in real-world environments.

Reference

[1] Xu, Y., Tong, X., & Stilla, U. (2021). Voxel-based representation of 3D point clouds: Methods, applications, and its potential use in the construction industry. In Automation in Construction (Vol. 126, p. 103675). Elsevier BV.

[2] Qi, C. R., Su, H., Mo, K., & Guibas, L. J. (2017). PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

[3] Shi, S., Wang, X., & Li, H. (2018). PointRCNN: 3D Object Proposal Generation and Detection from Point Cloud (Version 2). arXiv.

[4] Zhou, Y., & Tuzel, O. (2017). VoxelNet: End-to-End Learning for Point Cloud Based 3D Object Detection (Version 1). arXiv.

[5] Wang, Z., Li, Y., Chen, X., Zhao, H., & Wang, S. (2023). Uni3DETR: Unified 3D Detection Transformer (Version 1). arXiv.