Exploring different techniques for Facial Expression Recognition (FER)

Facial expression recognition (FER) is a pivotal task in computer vision with applications spanning from human-computer interaction to affective computing. In this project, we conduct a comparative analysis of three prominent model architectures for FER: a feature decomposition and feature reconstruction network (FDRL), a cross-fusion transformer-based network (POSTERV2), and YOLOv5. These architectures represent diverse approaches in leveraging deep learning techniques for facial expression analysis. We evaluate the performance of each model architecture on RAF-DB, which encompass a wide range of facial expressions under various contexts. The evaluation metrics include accuracy and number of parameters, which give comprehensive insights into the models’ capabilities in recognizing facial expressions accurately across different datasets. Our evaluations have shown that the POSTERV2 model outperforms the other models in terms of accuracy. We also present a demonstration of the YOLOv5 model running on a webcam and training a custom model to recognize “awake” and “sleep” expressions. Our findings provide valuable insights into the strengths and limitations of different model architectures for FER, which can guide the selection of appropriate models for specific applications.

Introduction

Facial expression recognition (FER) is a pivotal area of computer vision and artificial intelligence focused on identifying human emotions from facial expressions captured in images or videos. It holds significant implications for various fields, including human-computer interaction, safety, and entertainment. Over the years, researchers have explored different approaches to tackle this task, with deep learning approaches becoming more popular in recent years. Classical approaches to facial expression recognition typically relied on handcrafted features and traditional machine learning algorithms. These methods involved extracting facial features such as edges, corners, or texture descriptors from images, followed by training classifiers to recognize specific emotional states based on these features. Techniques like Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Decision Trees, or k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) were commonly employed for classification tasks. While classical approaches laid the foundation for facial expression recognition, they often encountered limitations. One major challenge was the reliance on manually engineered features, which might not fully capture the complexity and variability of facial expressions across different individuals, lighting conditions, and facial poses. Additionally, these methods struggled with handling variations in facial expressions caused by factors like occlusions, facial hair, or cultural differences, leading to reduced accuracy and robustness.

Deep learning methods have emerged as a more successful paradigm in facial expression recognition, offering significant improvements over classical techniques. Deep neural networks excel at learning representations directly from large-scale datasets via powerful computational resources, thus removing the need for handcrafted features. A key advantage of this is the ability to automatically capture important features within facial images, enabling more robust and accurate recognition of facial expressions under various conditions.

In this project, we explore three prominent deep neural network architectures for FER, including a convolutional neural network (CNN), POSTERV2, and YOLOv5. We show that PosterV2 outperforms the other models in terms of accuracy due to its cross-fusion transformer-based architecture. Each model was evaluated on RAF-DB, a benchmark dataset, and we compare their accuracies. Finally, we compare between the three models and discuss their advantages and limitations in the context of FER, before ending with a demonstration of the YOLOv5 model running on a webcam and training a custom model to recognize “awake” and “sleep” expressions.

Different Approaches to FER

1. Feature Decomposition and Reconstruction Learning (FDRL): Rethinking Facial Expression Information

Overview

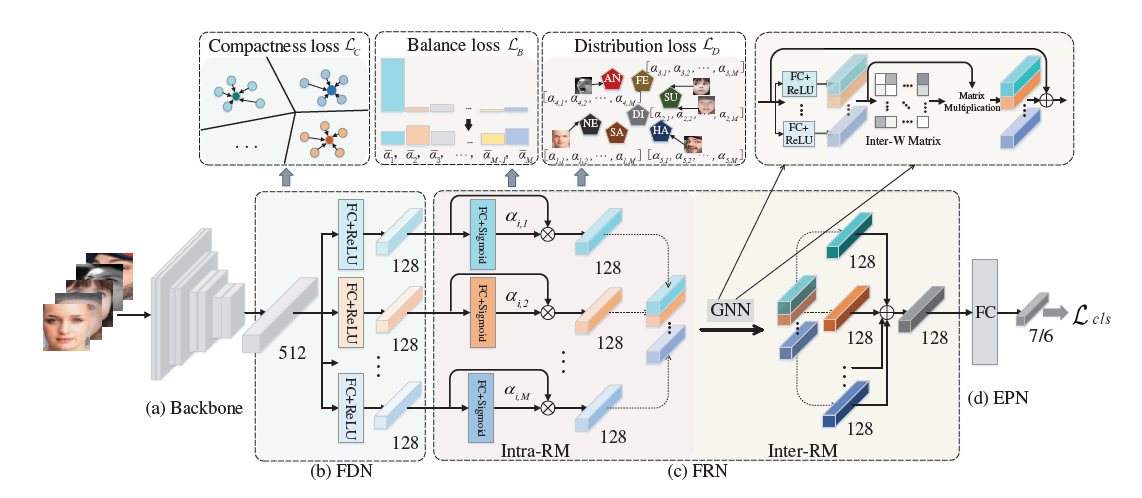

The FDRL model identifies that there can be large similarities between different expression (inter-class similarities) and differences within the same expression (intra-class discrepancies). Thus, facial expressions are interpreted as a combination of shared information (or “expression similarities”) between different expressions and unique information (or “expression-specific variations”) within the same expression. Expression similarities are represented by shared latent features between expressions, while expression-specific variations are denoted by the feature weights. This way, the model captures more fine-grained features from facial images. The model consists of 4 networks: Backbone Network, Feature Decomposition Network (FDN), Feature Reconstruction Network (FRN), and Expression Prediction Network (EPN).

Fig 1. FDRL model architecture [5]

Fig 1. FDRL model architecture [5]

Backbone Network

The backbone network is a convolutional neural network used to extract basic features. The paper uses ResNet-18 that is pretrained on the MS-Celeb-1M face recognition database as the model of choice for the backbone network.

Feature Decomposition Network

The FDN decomposes basic features from the backbone network into a set of facial action-aware latent features that encode expression similarities. A linear fully-connected layer and ReLU activation is used to extract each latent feature. Recognizing that a subset of latent features can be shared by different facial expressions due to expression similarities, a compactness loss \(L_C\) is used to penalize distances between latent features and the centers of those latent features. This encourages a more compact set of latent features and reduces variations for the same expression.

Feature Reconstruction Network

The FRN encodes expression-specific variations through an Intra-feature Relation Modeling module (Intra-RM) and Inter-feature Relation Modeling module (Inter-RM), and reassembles expression features.

Intra-RM constitutes multiple blocks that model intra-feature relationship, meaning the focus is on each individual latent feature. Each block consists of a linear fully-connected layer and sigmoid activation, and the blocks find the importance of each latent feature as represented by intra-feature relation weights. To ensure distribution of these weights are as close as possible for the same expression, a distribution loss \(L_D\) is used to penalize distances between weights belonging to the same expression category and the centers of those weights. This encourages weights representing different images in the same expression category to be closely distributed. To further counter imbalances of weight elements in the same weight vector for a particular image, a balance loss \(L_B\) is computed to distribute the elements in the weight vector. The module returns intra-aware features for each facial image.

Inter-RM, on the other hand, focuses on finding relationship across different latent features. To take into account multiple facial actions that can appear concurrently for each facial expression, a graph neural network is used to learn weights between intra-aware features returned from the Intra-RM module. A message network, comprising of a linear fully-connected layer and ReLU activation, first performs feature encoding on the intra-aware features. Then, a relation message matrix is represented as nodes in a graph, and relation importance between nodes are denoted by weights. Inter-aware features for each facial image are created based on the weighted sum of the corresponding nodes.

With both intra-aware and inter-aware features, importance-aware features are calculated through a linear combination of the 2 types of features. Finally, the summation of importance-aware features for each facial image represents the expression feature for that image.

Expression Prediction Network

The final part of the model is the expression classifier, which is a linear fully-connected layer. This layer simply receives an input of the reassembled expression features and returns a facial expression label. The classification loss \(L_{cls}\) is computed by finding the cross-entropy loss.

Loss Function

The 4 networks are jointly trained with end-to-end training, by minimizing the following cost function.

\[\text{Loss} = L_{cls} + \lambda_1L_C + \lambda_2L_B + \lambda_3L_D\]Training Implementation

The paper chooses to train the FDRL model on a TITAN X GPU for 40 epochs with a batch size of 64. The Adam optimization algorithm is selected with the learning rate further manually annealed.

2. POSTER V2: A simpler and stronger facial expression recognition network

Overview

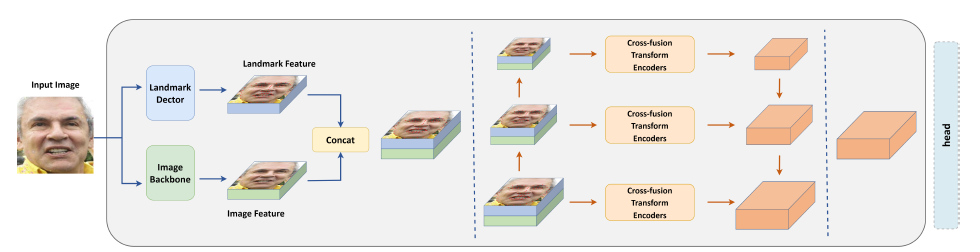

An alternative approach to FER is the POSTER V2 model, an enhanced version of the original POSTER model. The original POSTER model has 4 main features, namely a landmark detector, an image backbone, cross-fusion transformer encoders and a pyramid network. Given an input image, the landmark detector extracts detailed facial landmark features while the image backbone extracts generic image features. Following that, the landmark and image features are concatenated and scaled to different sizes, before interacting via cross-attention in separate cross-fusion transformer encoders for each scale. Finally, the model extracts and integrates the outputs of each encoder into a multi-scale landmark and image feature. Despite achieving state-of-the-art performance in FER, the architecture of the original POSTER model is highly complicated, resulting in expensive computational costs. Hence, POSTER V2 implements 3 key improvements on top of the original POSTER model architecture that not only reduce computational costs, but also enhance model performance.

Fig 2. Original POSTER model architecture [4]

Fig 2. Original POSTER model architecture [4]

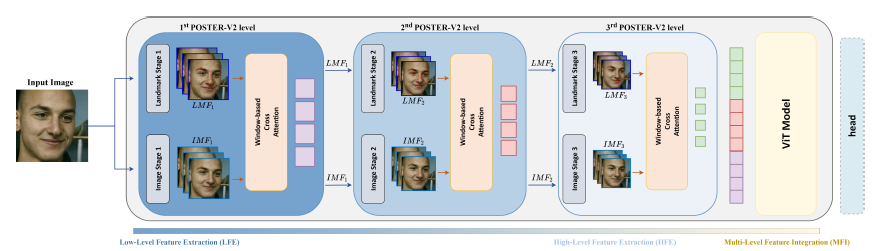

Fig 3. POSTER V2 model architecture [4]

Fig 3. POSTER V2 model architecture [4]

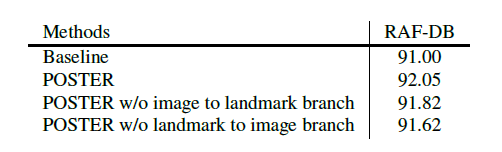

Improvement 1: Remove Image-to-Landmark Branch

A primary characteristic of the original POSTER model is its two-stream design that consists of both an image-to-landmark branch, and a landmark-to-image branch. To reduce computational cost, the POSTER V2 research team conducted an ablation study to determine which branch plays a more decisive role in model performance, so as to remove the less decisive branch. As seen from the results below, the landmark-to-image branch proved to be the more decisive one. The following explanation accounts for this trend from an intuitive perspective. In the landmark-to-image branch, image features are guided by landmark features, which are the query vectors in the cross-attention mechanism. Since landmark features highlight the most important regions of the face, it reduces discrepancies within the same class, which are emotions for FER tasks. Furthermore, it diverts focus away from face-prevalent regions, thus reducing similarities among different classes. Therefore, by retaining the landmark-to-image branch, POSTER V2 ensures that key FER issues such as intra-class discrepancy and inter-class similarity are mitigated. At the same time, removing the image-to-landmark branch enhances computational efficiency to a much more significant extent than the slight drop in model accuracy.

Fig 4. Removing image-to-landmark vs landmark-to-image branch [4]

Fig 4. Removing image-to-landmark vs landmark-to-image branch [4]

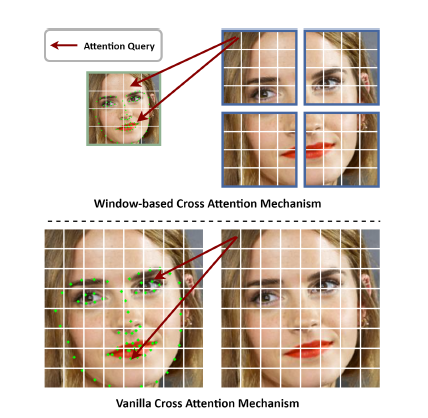

Improvement 2: Window-Based Cross-Attention

instead of the vanilla cross-attention mechanism used in the original POSTER model, POSTER v2 opted for window-based cross-attention. As depicted in the visualization below, the first step is to divide the image feature on the right into non-overlapping windows. For each window, the landmark feature is downsampled to the size of the window, following which the cross-attention between the image and landmark features is calculated. This cross-attention calculation is performed for all windows. Compared to the vanilla cross-attention mechanism in the original POSTER model, the time complexity of this step has been reduced from \(O(N^2)\) to \(O(N)\), thus enhancing the model’s computational efficiency.

Fig 5. Window-based cross-attention mechanism [4]

Fig 5. Window-based cross-attention mechanism [4]

Improvement 3: Multi-Scale Feature Extraction

The goal of multi-scale feature extraction is to capture both global and local patterns in the image. There are several reasons why this is important. First of all, facial expressions comprise fine details such as muscle movements, as well as broad features like face configurations. Furthermore, it makes the model robust to noise and occlusion, thus ensuring that the model performs well in real-world scenarios. It also helps the model adapt to input images in different resolutions.

Although both POSTER V2 and the original POSTER models utilized multi-scale feature extraction, their implementations are different. The original POSTER model implemented multi-scale feature extraction using the pyramid structure, as image and landmark features of different scales are passed through separate cross-fusion transformer encoders before their outputs are integrated at the end. On the contrary, POSTER V2 extracts multi-scale features directly from the landmark detector and image backbone, before integrating them using a 2-layered vanilla transformer, which enhances the performance of the model.

Data Augmentation

POSTER V2 used Random Horizontal Flipping and Random Erasing as data augmentation methods to improve the model’s ability to generalize and reduce overfitting. Random Horizontal Flipping involves randomly selecting a subset of images to flip along its vertical axis. Random Erasing involves randomly selecting a rectangular region within an image and replacing the pixel values in that region with random noise.

Computing Loss

POSTER V2 made use of the categorical cross-entropy loss function, where \(t_i\) is the ground truth and \(s_i\) is the predicted score for each class \(i\) in \(C\).

\[\text{Loss} = -\sum_{i}^{C} t_i log(s_i)\]3. YOLOv5

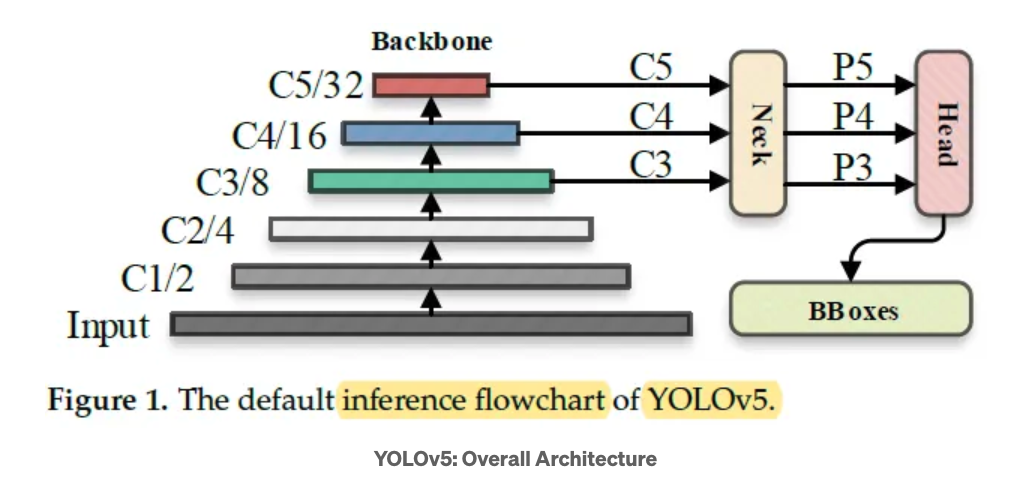

Lastly, another approach to FER is the use of the YOLOv5 (You Only Look Once) architecture, which is a popular object detection algorithm that builds upon the previous versions of the YOLO family of models. The architecture of YOLOv5 consists of a backbone network, neck network, and head network as shown in Fig 1.

Fig 6. The default inference flowchart of YOLOv5 [1]

Fig 6. The default inference flowchart of YOLOv5 [1]

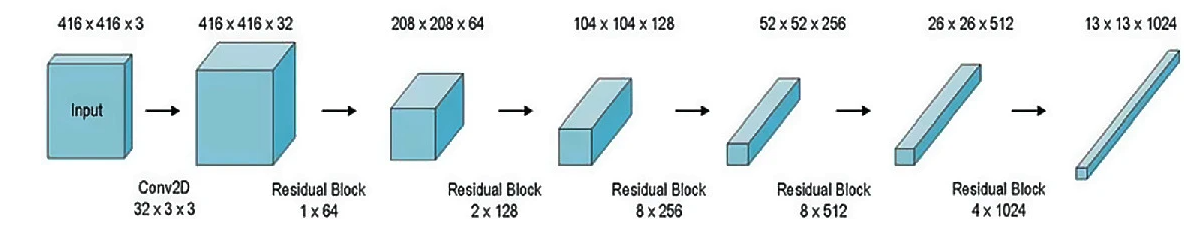

Backbone Network: The backbone network is responsible for extracting features from the input image. In YOLOv5, the CSPDarknet53 architecture is used as the backbone, which is a deep CNN with residual connections. It consists of multiple convolutional layers followed by residual blocks, which help in capturing both low-level and high-level features from the image.

Neck Network: The neck network of YOLOv5 employs a PANet (Path Aggregation Network) module. The PANet module fuses features from different scales to enhance the model’s ability to detect objects of various sizes. It consists of bottom-up and top-down pathways that connect features of different resolutions, to generate a multi-scale feature map that aids in detecting objects of different sizes.

Head Network: The head network of YOLOv5 is responsible for generating the final predictions It consists of several convolutional layers followed by a global average pooling layer and fully connected layers. These detection layers predict the bounding box coordinates, class probabilities, and other attributes for the detected objects. YOLOv5 uses anchor boxes to assist in predicting accurate bounding boxes for objects of different sizes.

Fig 7. Darknet-53 architecture [2]

Fig 7. Darknet-53 architecture [2]

Data Augmentation

YOLOv5 employs various data augmentation techniques to improve the model’s ability to generalize and reduce overfitting. These techniques include: Mosaic Augmentation, Copy-Paste Augmentation, Random Affine Transformations, MixUp Augmentation, Albumentations and Random Horizontal Flip.

Computing Loss

The YOLOv5 loss is determined by aggregating three distinct components:

- Classification Loss (BCE Loss): This evaluates the classification task’s error using Binary Cross-Entropy loss.

- Objectness Loss (BCE Loss): Utilizing Binary Cross-Entropy loss again, this component assesses the accuracy in determining object presence within a given grid cell.

- Localization Loss (CIoU Loss): Complete IoU loss is employed here to gauge the precision in localizing the object within its respective grid cell.

FER Application

Due to YOLOv5’s efficiency and speed, many papers have adapted it for facial expression recognition by training it on a dataset that includes facial images labeled with expression categories. With its small size and fast inference time, YOLOv5 is suitable for real-time applications such as emotion recognition in video calls, driver monitoring systems, and emotion-aware advertising. It can also be used in applications on low-powered edge devices such as smartphones and IoT devices.

Comparison of the Approaches

Performance Evaluation

We compare the performance of the three model architectures on RAF-DB, a popular dataset for benchmarking FER.

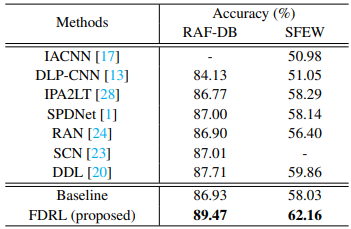

FDRL

Fig 8. Performance of FDRL on RAF-DB Dataset [5]

Fig 8. Performance of FDRL on RAF-DB Dataset [5]

The FDRL model achieved an accuracy of 89.47% on the RAF-DB dataset, which is a competitive result compared to other state-of-the-art models.

YoloV5

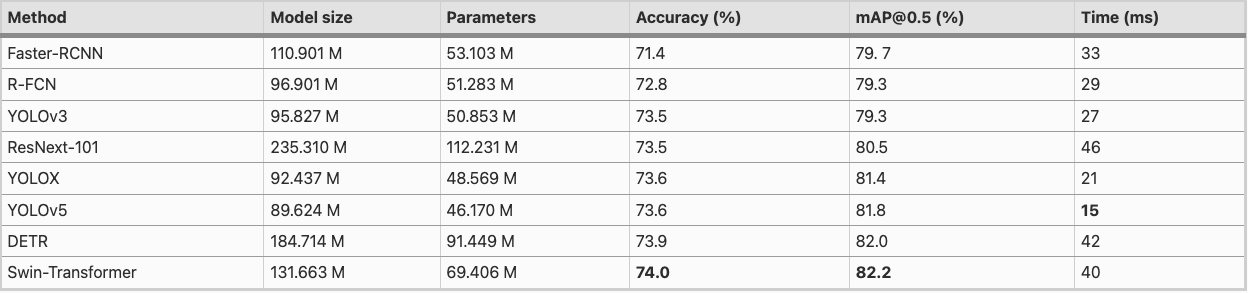

Fig 9. Different models experiment on RAF-DB Dataset [7]

Fig 9. Different models experiment on RAF-DB Dataset [7]

Evaluating YOLOv5 on the RAF-DB dataset gives us an accuracy of 73.6% and mAP@0.5 (%) of 81.8%, most notably, the inference time was only 15ms [7].

Poster V2

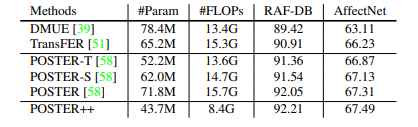

PosterV2, also known as Poster++, exhibits state-of-the-art performance on the FER task, outperforming the other models in terms of mean accuracy. Out of the three models, Poster++ achieved the highest accuracy on the RAF-DB dataset with an accuracy of 92.21% across all classes.

Fig 10. Performance, parameters and FLOPs of Poster V2 [4]

Fig 10. Performance, parameters and FLOPs of Poster V2 [4]

Despite acheiving SOTA results on FER, Poster++ maintains a number of parameters (43.7M) comparable to YoloV5 (46.2M). Thus, Poster++ is a much more memory efficient model for the FER task.

Advantages and Limitations of each approach

FDRL

FDRL is specifically designed to handle the nuances of facial expressions by distinguishing between shared and unique information across different expressions, which could enhance its sensitivity to subtle facial cues. The method’s decomposition and reconstruction process allows for a more detailed and nuanced understanding of facial features, potentially leading to higher accuracy in complex scenarios. However,the complexity of the model, with its multiple networks (Backbone, FDN, FRN, and EPN), could lead to higher computational costs and longer training times compared to more streamlined models. FDRL is also known to not handle noisy labels and ambiguous expressions well, which could limit its robustness in real-world scenarios [3]. FDRL also addresses intra-class discrepancy and inter-class similarity issues only using image features, but does not address scale sensitivity. Thus, the model is sensitive to image quality and resolution changes, and does not have consistent performance across scales. These limitations could affect its generalization across diverse datasets and robustness in real-world scenarios.

YoloV5

YOLOv5 is renowned for its speed and efficiency, making it highly suitable for real-time applications and deployment on edge devices. The model’s robustness and generalization capabilities are enhanced through various data augmentation techniques, making it versatile across different scenarios and conditions. While YOLOv5 offers a good balance between speed and accuracy, it may not achieve the same level of fine-grained accuracy in FER as more specialized models like POSTER V2, particularly in complex or nuanced expression recognition tasks. However, being designed primarily as an object detection framework, YOLOv5 will require additional finetuning to fully capture the subtleties of human facial expressions, as opposed to models specifically designed for FER. the model is also not designed to tackle challenges with FER such as scale sensitivity, occlusion, and noise, which could limit its ability to handle the FER task in real-world scenarios.

Poster V2

POSTER V2, with its transformer-based architecture, excels in capturing both global and local dependencies in the data, leading to state-of-the-art performance in FER, particularly noted for its high accuracy on the RAF-DB dataset. The model’s simplification over its predecessor by removing the image-to-landmark branch and employing window-based cross-attention and multi-scale feature extraction contributes to its computational efficiency while maintaining strong performance. Despite being lighter than its predecessor, POSTER V2 might still be relatively more computationally intensive than more traditional CNN models like YOLOv5, possibly affecting its deployment in real-time or resource-constrained environments. The model’s reliance on landmark detection might make it sensitive to errors or variations in landmark localization, potentially affecting its robustness across diverse or challenging datasets. However, among the three models, POSTER V2 stands out for its high accuracy and balance of computational efficiency, making it an attractive choice for FER applications requiring high accuracy and nuanced emotion recognition.

Conclusion

In this comprehensive exploration of facial expression recognition (FER), we’ve delved into three cutting-edge deep neural network architectures: FDRL, POSTER V2, and YOLOv5. Each model brings its unique strengths and considerations to the table, showcasing the diversity in approaches within the field of computer vision and artificial intelligence. FDRL’s focus on dissecting and reconstructing facial expression features allows for a nuanced understanding of expressions, potentially making it adept at handling complex emotional recognition tasks. However, its sophisticated architecture may lead to higher computational demands and longer training times, posing challenges for rapid deployment or application in resource-limited scenarios. On the other hand, YOLOv5 stands out for its speed and efficiency, traits that are crucial for real-time applications and deployment on edge devices. While it provides a robust general-purpose solution for object detection, including facial expressions, its adaptation to the subtleties of FER may require additional fine-tuning compared to models specifically designed for this task. POSTER V2, with its transformer-based design and focus on multi-scale feature extraction, achieves impressive accuracy in FER, outperforming the other models on the RAF-DB dataset. Its balance of computational efficiency and performance makes it an attractive option for FER, although its complexity could still pose challenges for deployment in constrained environments. The choice of model for a specific FER application depends on a variety of factors including the desired accuracy, computational resources, and the need for real-time processing. For applications requiring high accuracy and nuanced emotion detection, POSTER V2 appears to be the best choice. For scenarios where speed and efficiency are paramount, YOLOv5 offers a compelling solution. FDRL, with its detailed feature analysis, may be suited for research applications or scenarios where a deep understanding of facial expressions is required.

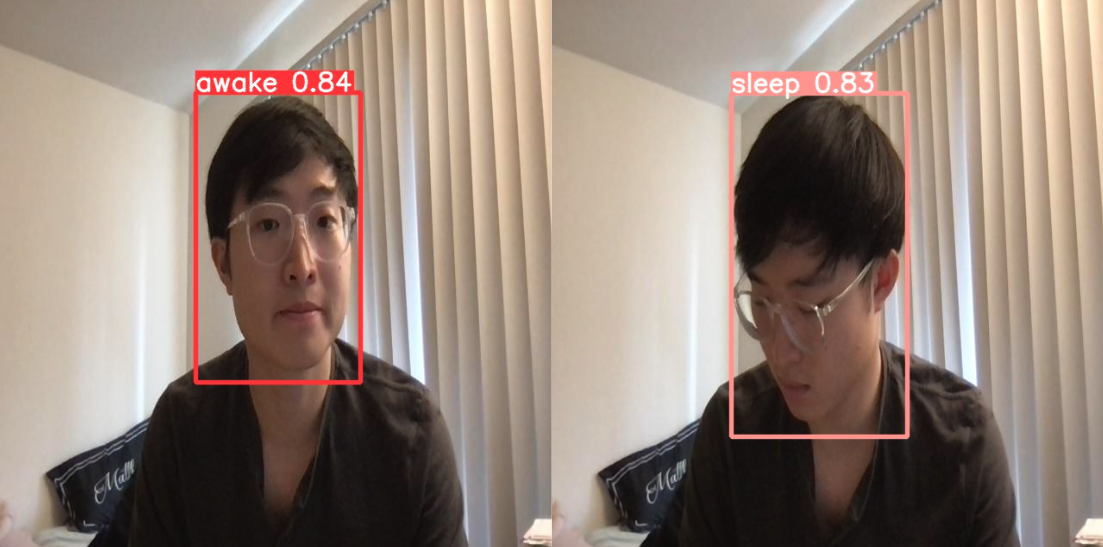

To understand the FER task further, we demonstrate below a YOLOv5 model running on a webcam and training a custom model to recognize “awake” and “sleep” expressions. This demonstration shows a potential application of YOLOv5 in real-time FER, and the process of training custom models for specific facial expressions.

Bonus:

1. Recognizing our own expressions

On top of studying the approaches to FER on paper, we also wanted to run an existing codebase to try out one of the models on our own. We found a YOLOv5 pre-trained model and ran it on our own webcam. This model was trained on the AffectNet dataset, which has 420,299 facial expressions. It also detects 8 basic facial expressions: anger, contempt, disgust, fear, happy, neutral, sad, surprise.

Fig 11. YOLOv5-FER inference on our Webcam

Fig 11. YOLOv5-FER inference on our Webcam

2. Training our own “awake” and “sleep” class

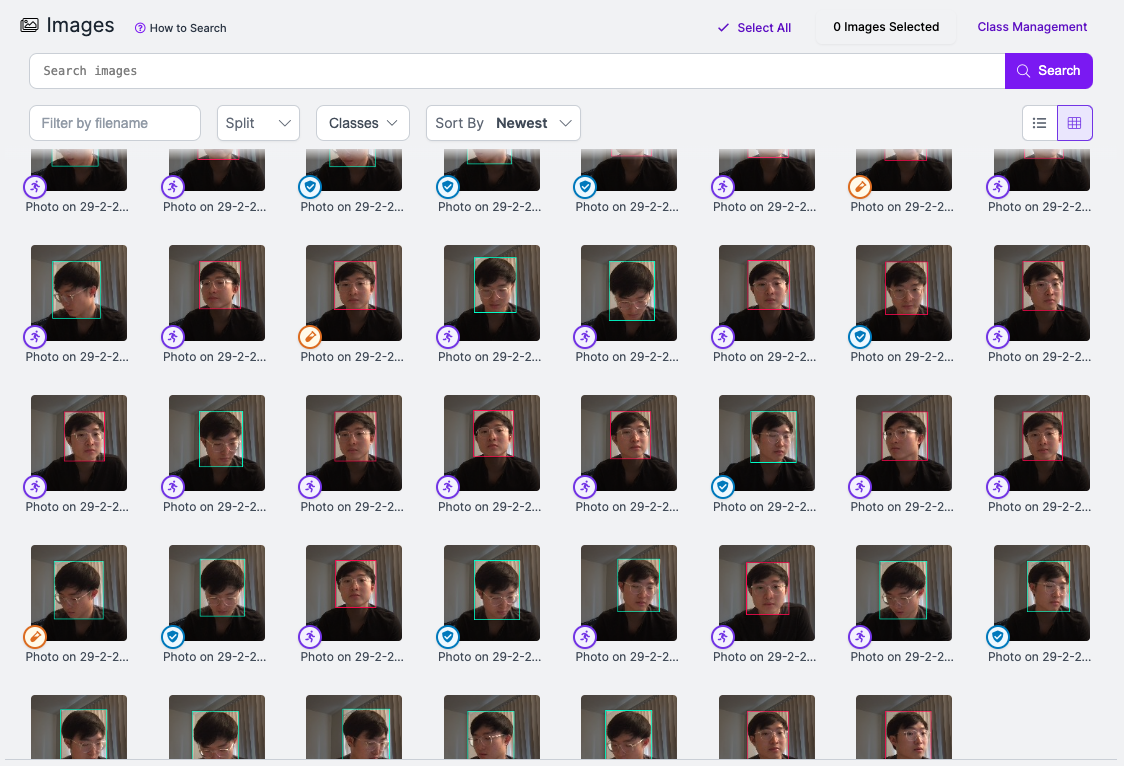

To supplement our project, we wanted to explore and train a model with two new custom classes for facial expression recognition. We collated our own dataset of 40 images (20 awake, 20 sleep) and annotated them using RoboFlow. Subsequently, we used the YOLOv5 architecture to train our own custom model.

Fig 12. Image Annotations on Roboflow

Fig 12. Image Annotations on Roboflow

We used transfer learning from yolov5s.pt and trained our model for 150 epochs using a single Google Colab T4 GPU.

!python train.py --img 416 --batch 16 --epochs 150 --data {dataset.location}/data.yaml --weights yolov5s.pt --cache

Model summary: 157 layers, 7015519 parameters, 0 gradients, 15.8 GFLOPs

| Class | Images | Instances | P | R | mAP50 | mAP50-95 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| all | 8 | 8 | 0.76 | 0.597 | 0.781 | 0.696 |

| awake | 8 | 2 | 0.714 | 0.5 | 0.638 | 0.56 |

| sleep | 8 | 6 | 0.806 | 0.695 | 0.924 | 0.831 |

Run Inference on Trained Weights:

Fig 13. Test Images with Annotations

Fig 13. Test Images with Annotations

Reference

[1] Liu H, Sun F, Gu J, Deng L. SF-YOLOv5: A Lightweight Small Object Detection Algorithm Based on Improved Feature Fusion Mode. Sensors. 2022; 22(15):5817. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22155817

[2] Lu, Z., Lu, J., Ge, Q., Zhan, T. Multi-object detection method based on Yolo and ResNet Hybrid Networks. 2019 IEEE 4th International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM). (2019) https://doi.org/10.1109/icarm.2019.8833671

[3] Lukov, T., Zhao, N., Lee, G. H., & Lim, S.-N. (2022). Teaching with Soft Label Smoothing for Mitigating Noisy Labels in Facial Expressions. EECV (pp. 648-665). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19775-8_38

[4] Mao, Jiawei and Xu, Rui and Yin, Xuesong and Chang, Yuanqi and Nie, Binling and Huang, Aibin. POSTER V2: A simpler and stronger facial expression recognition network. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12149. (2023) https://arxiv.org/pdf/2301.12149

[5] Ruan, D., Yan, Y., Lai, S., Chai, Z., Shen, C., Wang, H. Feature decomposition and reconstruction learning for effective facial expression recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 7660–7669 (2021) https://arxiv.org/pdf/2104.05160

[6] Ultralytics. YOLOV5. PyTorch Hub. https://pytorch.org/hub/ultralytics_yolov5/

[7] Zhong, H., Han, T., Xia, W. et al. Research on real-time teachers’ facial expression recognition based on YOLOv5 and attention mechanisms. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2023, 55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13634-023-01019-w