Text Guided Image Editing using Diffusion

In this study, we explore the advancements in image generation, particularly focusing on DiffEdit, an innovative approach leveraging text-conditioned diffusion models for semantic image editing (Couairon et al., 2022 [1]). Semantic image editing aims to modify images in response to textual prompts, enabling precise and context-aware alterations. A thorough comparison between DiffEdit and various traditional and deep learning-based methodologies have been conducted, highlighting its consistency and effectiveness in semantic editing tasks. Additionally, we introduce an interactive framework that integrates DiffEdit with BLIP and other text-to-image models to create a comprehensive end-to-end generation and editing pipeline. Moreover, we delve into a novel technique for text-guided mask generation within DiffEdit, proposing a method for object segmentation based solely on textual queries. We emphasize the importance of integrating AI safety and ethical considerations, ensuring our advancements are both technologically groundbreaking and responsibly implemented.

- Introduction

- Previous Works

- Dive into DiffEdit

- Experiment and Benchmarks

- Our Ideas

- Ethics Impact

- Conclusion

- Reference

Introduction

What is Image Editing

Image editing refers to the process of altering or manipulating digital images. It encompasses a wide range of tasks, including color correction, cropping, resizing, and retouching. It has a variety of applications, such as photography, graphic design, and digital art.

The recent surge in image editing technology, driven by advancements in deep learning, has revolutionized the field. Deep learning-based methods have showcased impressive abilities in generating and modifying images, paving the way for a diverse array of applications. These include image inpainting as evidenced by (Yu et al., 2018 [2]), style transfer as explored by (Jing et al., 2019 [3]), and many others. These developments have birthed a novel paradigm in image editing, particularly notable in text-guided image editing.

This innovative approach is able to find significant applications in the fashion industry. Designers now have the capability to input descriptions of desired styles, colors, and patterns, and watch as AI systems adapt existing designs to these specifications. This method offers a more efficient pathway for testing and developing new design concepts.

Furthermore, the impact of text-guided image editing can extend into augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) environments. Here, users can interact with virtual objects, either superimposed onto the real world or within entirely virtual settings. Text-guided image editing introduces an intuitive interface, allowing users to modify these virtual objects—altering aspects like color, size, texture, or position—through simple text or voice commands. This not only enhances user experience but also broadens the scope of interactivity within these digital environments.

Semantic Image Editing

Semantic image editing, a subset within the broader realm of image editing, concentrates on refining and modifying images in accordance with textual descriptions. This method is effective for executing precise and complicated modifications, as it enables users to articulate their desired changes in natural language. The essence of semantic image editing lies in its complexity; it demands the model to not only comprehend the textual description but also to apply suitable alterations to the image accurately.

This challenge, however, is what endows semantic image editing with its vast potential for application across a wide spectrum of image editing tasks. Its capabilities extend to other image editing tasks such as the removal of objects, colorization of images, and the transfer of styles. This versatility highlights the significance of semantic image editing in the comtempory landscape of digital image manipulation, which is why we have chosen to focus on this area in our study.

Previous Works

The field of semantic image editing has seen a surge in innovation, particularly with the advent of deep learning-based methods. These methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in generating and modifying images, particularly in response to textual prompts. Here, we provide an overview of the various approaches that have been developed to tackle semantic image editing tasks.

Classical Approaches

Before the rise of deep learning, semantic image editing was almost impossible to achieve. The complexity of the task, combined with the lack of sophisticated models, made it a daunting challenge. One method of image editing is object-based image editing (OBIE) (Barret & Cheney, 2002 [4]), which involved manual placement of pivot points and selecting objects by hand, making them both time-consuming and limited in scope.

The emergence of deep learning has dramatically expanded the potential of semantic image editing. Groundbreaking technologies like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and transformers have revolutionized this field. There are two main approaches to semantic image editing using GANs and transformers: training an end-to-end model with a proxy task then adapting it to the editing task, and training a model to optimize the image itself to match the text query.

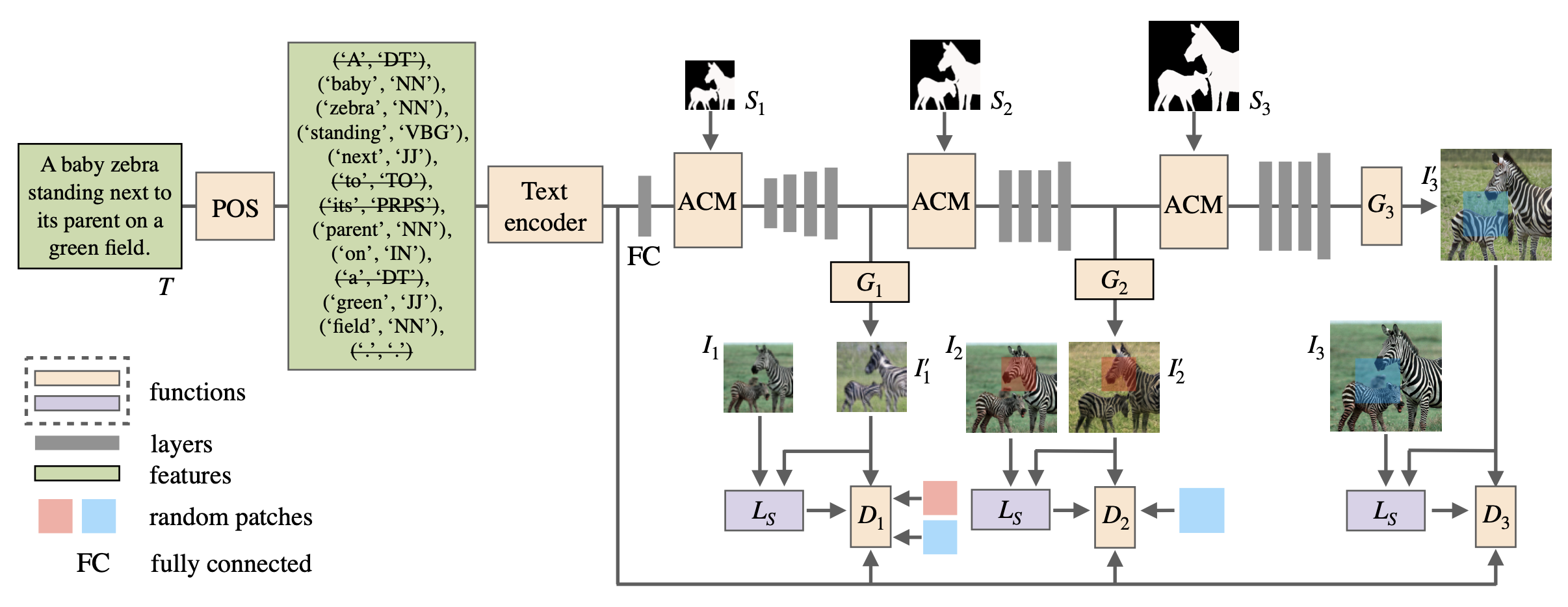

RefinedGAN (Li et al., 2020 [5]) is an example of model with a proxy task. This innovative model stands out due to its ability to generate desired images without the need for fine-grained, pixel-labelled semantic maps. This means that even when provided with simple masks, RefinedGAN can effectively interpret and act upon natural language descriptions to produce the intended images. The basic architecture of the model is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Architecture of RefinedGAN. [5]

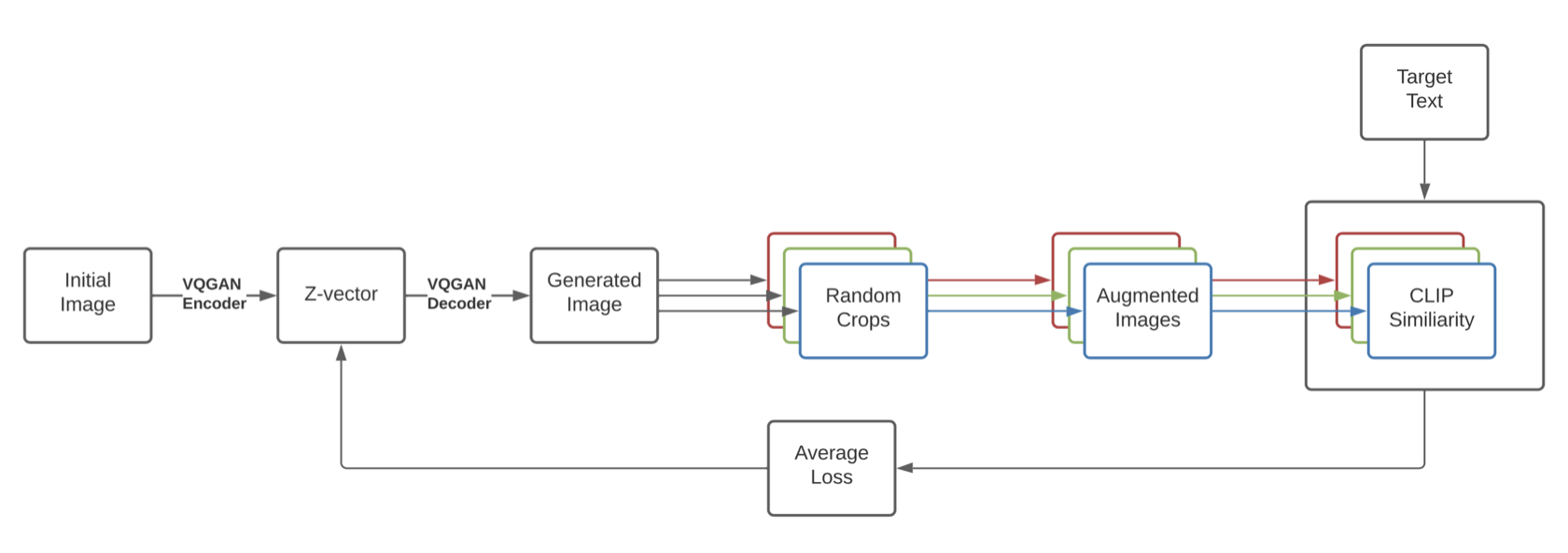

On the other hand, VQGAN-CLIP (Crowson et al., 2022 [6]) is a representation of optimization on the image itself to match the text query. At the core of this model is the CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pretraining) component, which functions as a mechanism to assess how accurately a text prompt describes an image. This model works by using the multimodal encoder to use CLIP to evaluate the similarity of text and image pair and backpropagating to the latent space of the image generator. We iteratively update the candidate generation until it is sufficiently similar to the target text. The basic architecture of the model is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2. Architecture of VQGAN-CLIP. [6]

These methods, while effective, work best when the models is optimized with a powerful generative network and need to comsume great computational resources (Couairon et al., 2022 [1]).

Diffusion Approaches

Building on the exploration of classical image editing methods, it is important to highlight the transformative role diffusion models play in this domain. Such models enhance images starting from random noise and are ideal for inpainting by filling in masked areas naturally.

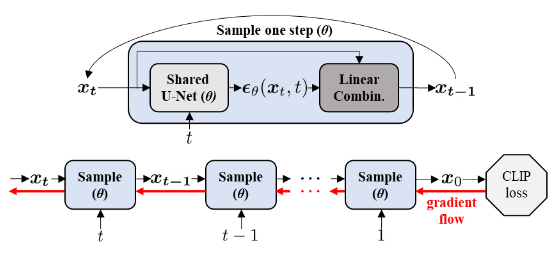

One of such approaches is DiffusionCLIP, in which case the CLIP loss and target text are leveraged during gradient descent to update the model parameters (Kim & Ye, 2021 [7]). Fig. 3 demonstrates how the CLIP loss is incorporated into the gradient flow of fine-tuning DiffusionCLIP. But it is worth noting that this approach has a high computational cost since one model is fine-tuned for each input image.

Figure 3. Gradient flow of fine-tuning DiffusionCLIP with CLIP Loss. [7]

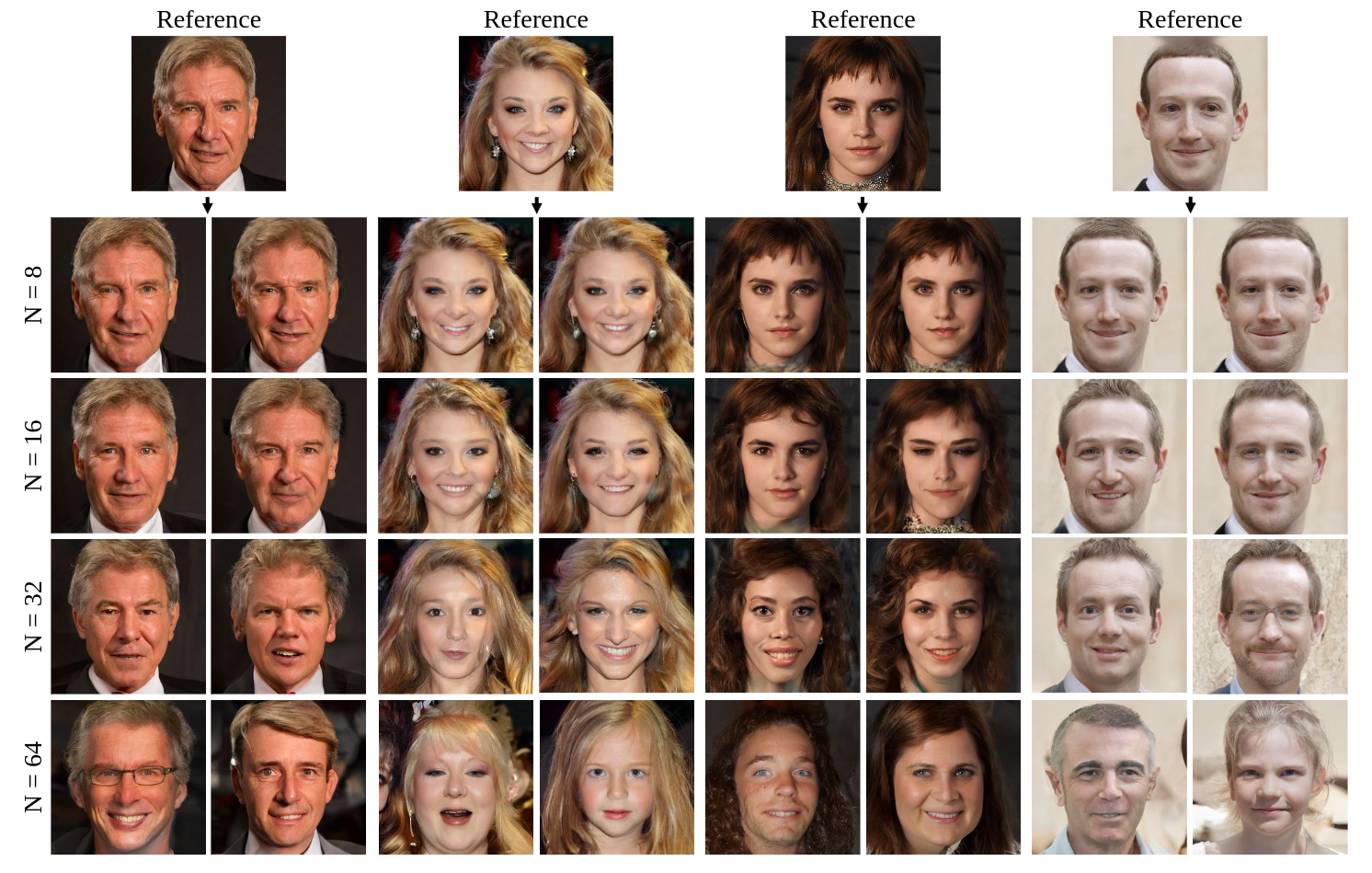

Another approach is ILVR, i.e. Intermediate Latent Variable Refinement, which introduces a decoding constraint to ensure that the downscaled versions of both the input and the decoded images remain closely aligned (Choi et al., 2021 [8]). Using this method, image sampling is controlled by an reference image. Fig. 4 shows how different downsampling factors N affect the output image: when N is small (like 8), the outputs are similar to the reference images, but when N gets bigger, facial features begin to change, up to a point where only the color scheme remains from the reference.

Figure 4. Effect of downsampling factor on ILVR. [8]

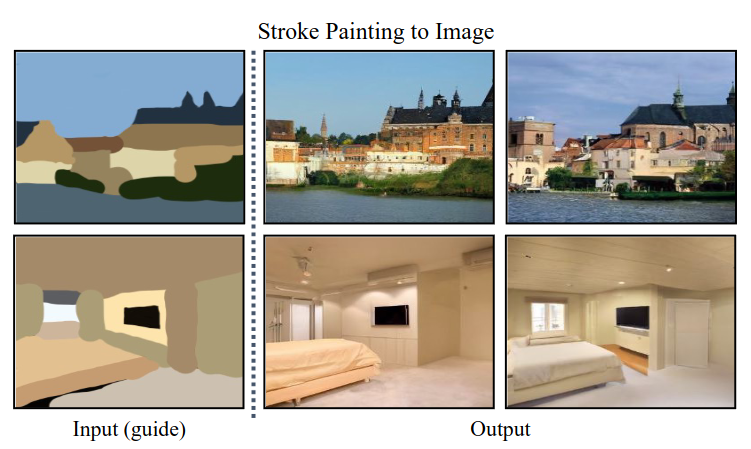

SDEdit is also a significant diffusion approach that features iterative refinement to produce high quality outputs (Meng et al., 2021 [9]). It uses SDE (Stochastic Differential Equations) to model the diffusion process with modifications in the noise space to reflect meaningful changes in the image space. It was developed with the purpose of converting basic sketches into fully-realized, realistic images, as shown in Fig. 5. Nonetheless, it is also useful in conditionally denoising images with respect to a text query, which allows for easy comparison to the main subject of the study, i.e. DiffEdit.

Figure 5. Example of SDEdit application. [9]

Dive into DiffEdit

In many cases, semantic image edits can be restricted to only a part of the image, leaving other parts unchanged. However, the input text query does not explicitly identify this region, and a naive method could allow for edits all over the image, risking to modify the input in areas where it is not needed. To circumvent this, DiffEdit propose a method to leverage a text-conditioned diffusion model to infer a mask of the region that needs to be edited. Starting from a DDIM encoding of the input image, DiffEdit uses the inferred mask to guide the denoising process, minimizing edits outside the region of interest.

Before delving into the intricate workings of DiffEdit, it’s essential to lay the groundwork by understanding some foundational concepts that it builds upon: DDIM (Song et al., 2021 [10]) and Classifier-Free Guidance (Ho & Salimans, 2022 [11]). These elements are vital for grasping how DiffEdit achieves its targeted editing prowess.

Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM)

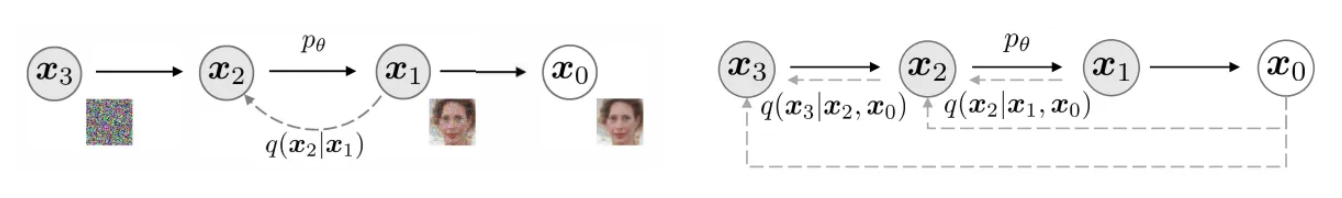

DDIM, short for Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models, is a variant of the diffusion models used for generating or editing images (Song et al., 2021 [10]). One problem with the DDPM process is the speed of generating an image after training. DDIMs accelerate this process by optimizing the number of steps needed to denoise an image, making it more efficient while maintaining the quality of the generated images (with a little quality tradeoff). It does so by redefining the diffusion process as a non-Markovian process. The best part about DDIMs is they can be applied after training a model, so DDPM models can easily be converted into a DDIM without retraining a new model. Fig. 6 shows the difference between the twi paradigms.

Figure 6. Graphical models for diffusion (left) and non-Markovian (right) inference models. [10]

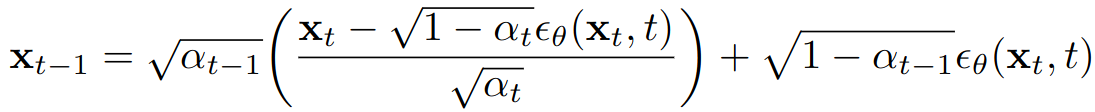

The reverse diffusion process in Denoising Diffusion Implicit Models (DDIM) serves as a fundamental mechanism allowing these models to reconstruct or generate images by methodically reversing the diffusion process that gradually transforms an image into random noise (Song et al., 2021 [10]). This process is central to understanding how DDIM and, by extension, technologies like DiffEdit function, enabling them to create detailed and precise image edits or generate images from textual descriptions. A simplified overview of the reverse diffusion process has been provided, avoiding deep mathematical complexities (Weng, 2021 [12]). The denoising formula for DDIM models is illustrated below in Fig. 7.

Figure 7. DDIM Denoising Formula. [1]

Importantly, instead of randomly walking back through the noise levels, DDIM uses a deterministic approach to carefully control the denoising path (Song et al., 2021 [10]). Thus we no longer have to use a Markov Chain since Markov Chains are used for probabilistic processes. We can use a Non-Markovian process, which allows us to skip steps.

Classifier-Free Guidance

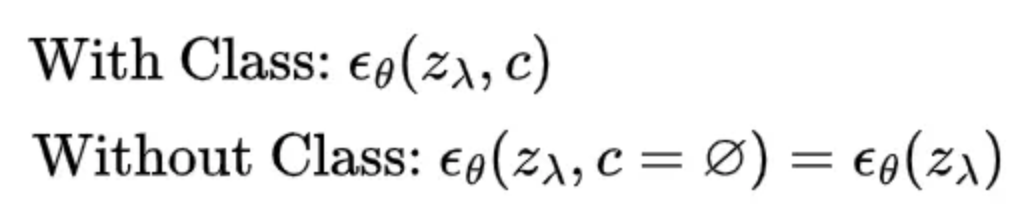

Classifier-Free Guidance (CFG) is a technique used to steer the generation process of a model towards a specific outcome without relying on a separate classifier model (Ho & Salimans, 2022 [11]). In traditional guided diffusion models, a classifier is often used in tandem with the diffusion model to ensure the generated images adhere to certain criteria. However, Classifier-Free Guidance simplifies this by eliminating the need for a separate classifier. Instead, it modifies the diffusion process itself to guide the generation towards the desired output. This is achieved in two key steps (Ho & Salimans, 2022 [11]):

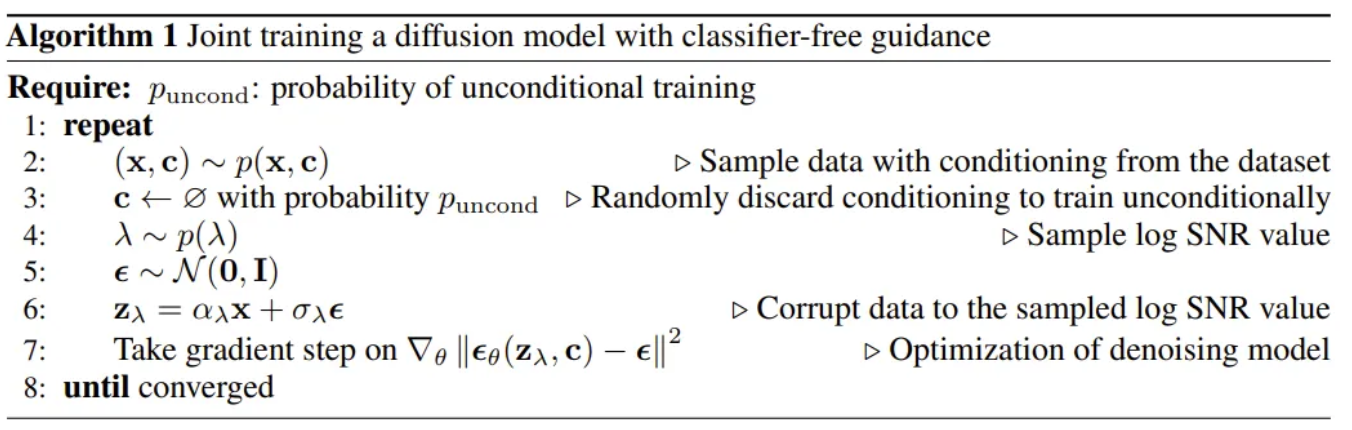

Training Phase:

Figure 8. Noise estimation model with and without class (null). [11]

During training, the model learns to generate outputs based on a wide range of inputs, including those without specific class labels. With a probability \(p_{\text{uncond}}\), we make some of the classes null classes. This approach enables the model to understand the underlying distribution of the data more broadly, rather than being constrained to specific labeled classes. The training algorithm is shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9.

Figure 9. Training with Classifier-Free Guidance. [11]

Generation Phase:

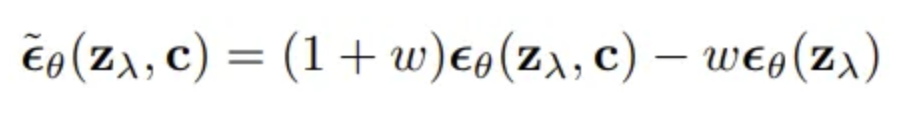

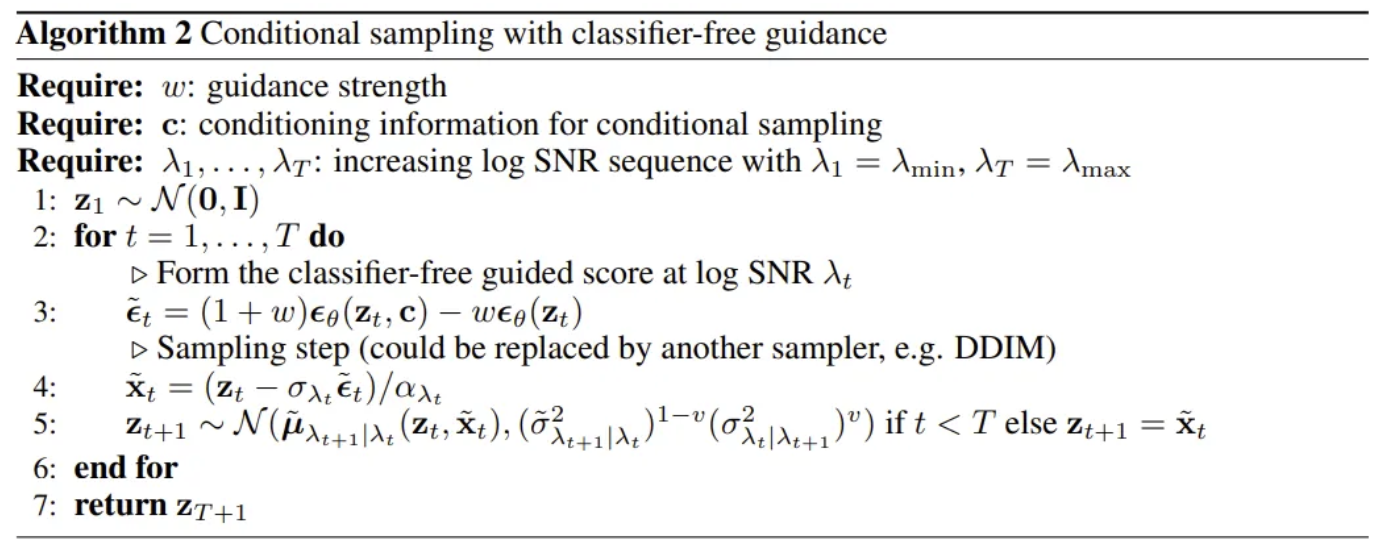

Figure 10. Noise model parameterization for Classifier-Free Guidance. [11]

The noise prediction requires two forward passes of the same image, zₜ. One forward pass calculates the predicted noise not conditioned on a desired class, and the other calculates the predicted noise conditioned on the desired class information. When generating new content, CFG employs a technique called “guidance scale” or “temperature,” which adjusts the strength of the model’s predictions towards certain attributes or themes. By tweaking this scale, users can control how closely the output adheres to the desired attributes without the need for an external classifier. The sampling algorithms are shown in Fig. 10 (for noise) and Fig. 11.

Figure 11. Sampling with Classifier-Free Guidance. [11]

By utilizing DDIM for efficient and precise encoding of the input image and incorporating Classifier-Free Guidance to direct the editing process without the need for additional classifiers, DiffEdit sets the stage for sophisticated image editing. These technologies allow DiffEdit to infer a mask of the region to be edited based on the text input, ensuring that changes are made only where intended. This approach not only preserves the integrity of the unedited portions of the image but also provides a high level of control and specificity in the editing process (Couairon et al., 2022 [1]).

Three Steps of DiffEdit

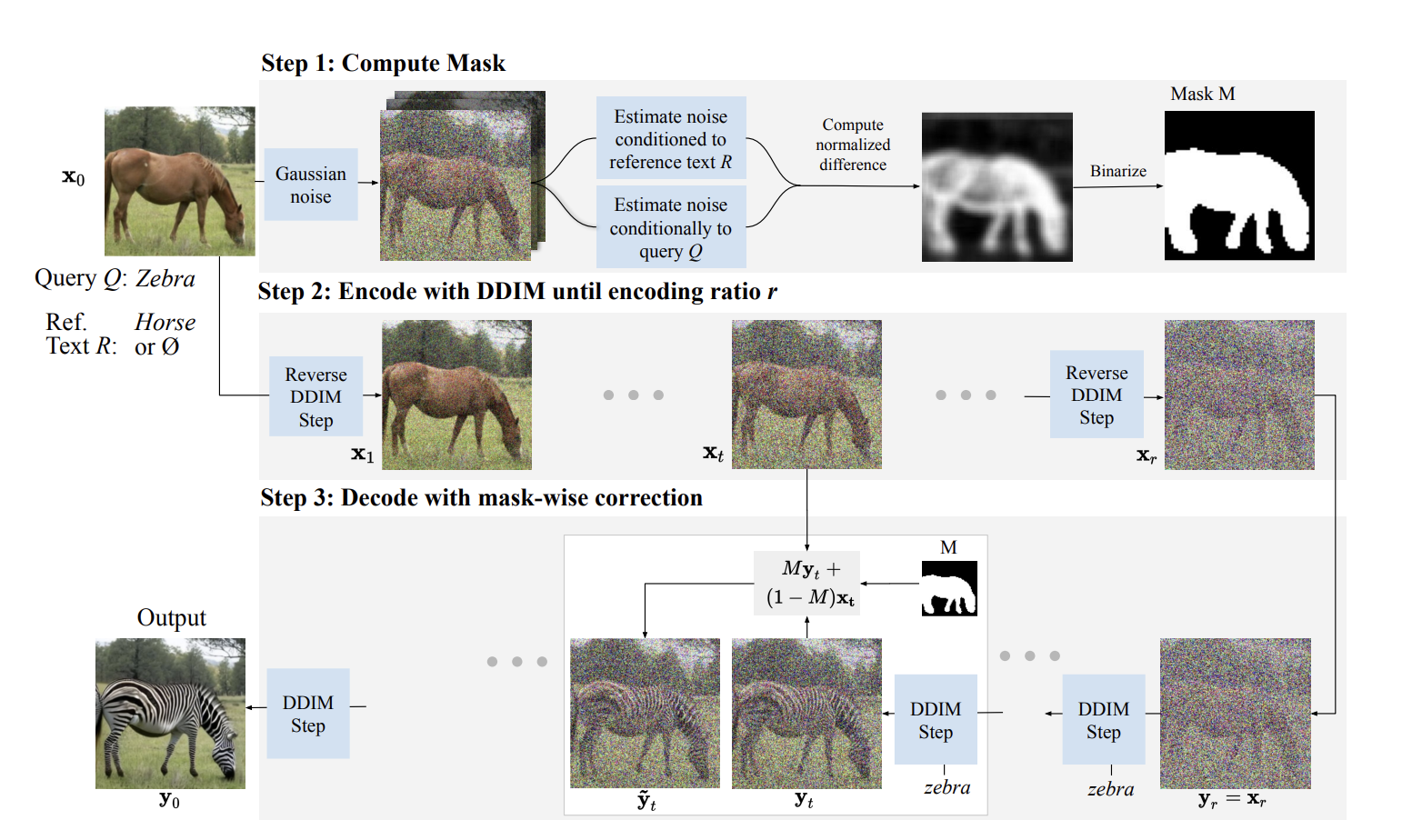

With this knowledge ready, let’s take a look at the three steps of DiffEdit (Couairon et al., 2022 [1]).

Figure 12. Three Steps of DiffEdit. [1]

-

Step one: Mask Generation

When the denoising an image, a text-conditioned diffusion model will yield different noise estimates given different text conditionings. We can consider where the estimates are different, which gives information about what image regions are concerned by the change in conditioning text. For instance, in Fig. 12, the noise estimates conditioned to the query zebra and reference text horse are different on the body of the animal, where they will tend to decode different colors and textures depending on the conditioning. For the background, on the other hand, there is little change in the noise estimates. The difference between the noise estimates can thus be used to infer a mask that identifies what parts on the image need to be changed to match the query by binarized with a threshold. The masks generally somewhat overshoot the region that requires editing, this is beneficial as it allows it to be smoothly embedded in it’s context.

def get_mask(model, src, dst, init_latent, n: int, ddim_steps,

clamp_rate:float=3):

device = model.device

repeated = repeat_tensor(init_latent, n)

src = repeat_tensor(src, n)

dst = repeat_tensor(dst, n)

noise = torch.randn(init_latent.shape, device=device)

scheduler = DDIMScheduler(num_train_timesteps=model.num_timesteps,

trained_betas=model.betas.cpu().numpy())

scheduler.set_timesteps(ddim_steps, device=device)

noised = scheduler.add_noise(repeated, noise,

scheduler.timesteps[ddim_steps // 2]

)

t = scheduler.timesteps[ddim_steps // 2]

t_ = torch.unsqueeze(t, dim=0).to(device)

pre_src = model.apply_model(noised, t_, src)

pre_dst = model.apply_model(noised, t_, dst)

# consider to add smooth method

subed = (pre_src - pre_dst).abs_().mean(dim=[0, 1])

max_v = subed.mean() * clamp_rate

mask = subed.clamp(0, max_v) / max_v

def to_binary(pix):

if pix > 0.5:

return 1.

else:

return 0.

mask = mask.cpu().apply_(to_binary).to(device)

return mask

https://github.com/Xiang-cd/DiffEdit-stable-diffusion

This point underscores the innovative efficiency of the method, capitalizing on the inherent capabilities of text-conditioned diffusion models. It ingeniously bypasses the conventional need for extensive training or model adaptation. The method can generate or modify images in a context-aware manner without the necessity for additional, costly training phases.

-

Step two: Encoding

We encode the input image \(x_0\) in the implicit latent space at timestep \(r\) with the DDIM encoding function \(E_r\). This is done with the unconditional model, i.e. using conditioning text \(∅\), so no text input is used for this step.

This approach allows us to strategically move backwards into a prior latent space that contains noise. By doing so, we are setting the stage to pivot and proceed in a new direction, specifically towards the generation of the target image. This reverse navigation through latent spaces enables the model to utilize pre-existing noise patterns to facilitate the transition towards the desired outcome, thereby leveraging the intrinsic capabilities of the diffusion process.

def sample(self, x, steps=20, t_start=None, t_end=None, order=3, skip_type='time_uniform',

method='singlestep', lower_order_final=True, denoise_to_zero=False, solver_type='dpm_solver',

atol=0.0078, rtol=0.05, record_process=False, record_list=None

):

t_0 = 1. / self.noise_schedule.total_N if t_end is None else t_end

t_T = self.noise_schedule.T if t_start is None else t_start

device = x.device

if method == 'adaptive':

with torch.no_grad():

x = self.dpm_solver_adaptive(x, order=order, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, atol=atol, rtol=rtol,

solver_type=solver_type)

elif method == 'multistep':

assert steps >= order

timesteps = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, N=steps, device=device)

assert timesteps.shape[0] - 1 == steps

with torch.no_grad():

vec_t = timesteps[0].expand((x.shape[0]))

model_prev_list = [self.model_fn(x, vec_t)]

t_prev_list = [vec_t]

# Init the first `order` values by lower order multistep DPM-Solver.

for init_order in range(1, order):

vec_t = timesteps[init_order].expand(x.shape[0])

x = self.multistep_dpm_solver_update(x, model_prev_list, t_prev_list, vec_t, init_order,

solver_type=solver_type)

if record_process:

record_list.append(x.cpu())

model_prev_list.append(self.model_fn(x, vec_t))

t_prev_list.append(vec_t)

# Compute the remaining values by `order`-th order multistep DPM-Solver.

for step in range(order, steps + 1):

vec_t = timesteps[step].expand(x.shape[0])

if lower_order_final and steps < 15:

step_order = min(order, steps + 1 - step)

else:

step_order = order

x = self.multistep_dpm_solver_update(x, model_prev_list, t_prev_list, vec_t, step_order,

solver_type=solver_type)

if record_process:

record_list.append(x.cpu())

for i in range(order - 1):

t_prev_list[i] = t_prev_list[i + 1]

model_prev_list[i] = model_prev_list[i + 1]

t_prev_list[-1] = vec_t

# We do not need to evaluate the final model value.

if step < steps:

model_prev_list[-1] = self.model_fn(x, vec_t)

elif method in ['singlestep', 'singlestep_fixed']:

if method == 'singlestep':

timesteps_outer, orders = self.get_orders_and_timesteps_for_singlestep_solver(steps=steps, order=order,

skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T,

t_0=t_0, device=device)

elif method == 'singlestep_fixed':

K = steps // order

orders = [order, ] * K

timesteps_outer = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, N=K, device=device)

for i, order in enumerate(orders):

t_T_inner, t_0_inner = timesteps_outer[i], timesteps_outer[i + 1]

timesteps_inner = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T_inner.item(), t_0=t_0_inner.item(),

N=order, device=device)

lambda_inner = self.noise_schedule.marginal_lambda(timesteps_inner)

vec_s, vec_t = t_T_inner.tile(x.shape[0]), t_0_inner.tile(x.shape[0])

h = lambda_inner[-1] - lambda_inner[0]

r1 = None if order <= 1 else (lambda_inner[1] - lambda_inner[0]) / h

r2 = None if order <= 2 else (lambda_inner[2] - lambda_inner[0]) / h

x = self.singlestep_dpm_solver_update(x, vec_s, vec_t, order, solver_type=solver_type, r1=r1, r2=r2)

if denoise_to_zero:

x = self.denoise_to_zero_fn(x, torch.ones((x.shape[0],)).to(device) * t_0)

return x

https://github.com/Xiang-cd/DiffEdit-stable-diffusion

-

Step three: Decoding with Mask Guidance

After obtaining the latent \(x_r\), we decode it with our diffusion model conditioned on the editing text query \(Q\), e.g. zebra in the example. We use our mask \(M\) to guide this diffusion process. Outside the mask \(M\), the edited image should in principle be the same as the input image. We guide the diffusion model by replacing pixel values outside the mask with the latents \(x_t\) inferred with DDIM encoding, which will naturally map back to the original pixels through decoding. The mask-guided DDIM update can be written as \(\bar{y}_t = My_t + (1−M)x_t\), where \(y_t\) is computed from \(y_{t−dt}\) with Eq. 2, and \(x_t\) is the corresponding DDIM encoded latent. The encoding ratio \(r\) determines the strength of the edit: larger values of \(r\) allow for stronger edits that allow to better match the text query, at the cost of more deviation from the input image which might not be needed.

The encoding ratio \(r\) plays a pivotal role in determining the intensity of the edit. Higher values of \(r\) empower more substantial edits, enabling a closer match to the text query. However, this comes at the expense of greater deviation from the original input image, which might not always be desirable. This interplay between alignment and deviation represents the core tradeoff that needs careful consideration during the editing process.

def sample_edit(self, x, steps=20, t_start=None, t_end=None, order=3, skip_type='time_uniform',

method='singlestep', lower_order_final=True, denoise_to_zero=False, solver_type='dpm_solver',

atol=0.0078, rtol=0.05, record_list=None, mask=None

):

t_0 = 1. / self.noise_schedule.total_N if t_end is None else t_end

t_T = self.noise_schedule.T if t_start is None else t_start

device = x.device

if record_list is not None:

assert len(record_list) == steps

if method == 'adaptive':

with torch.no_grad():

x = self.dpm_solver_adaptive(x, order=order, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, atol=atol, rtol=rtol,

solver_type=solver_type)

elif method == 'multistep':

assert steps >= order

timesteps = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, N=steps, device=device)

assert timesteps.shape[0] - 1 == steps

with torch.no_grad():

vec_t = timesteps[0].expand((x.shape[0]))

model_prev_list = [self.model_fn(x, vec_t)]

t_prev_list = [vec_t]

# Init the first `order` values by lower order multistep DPM-Solver.

for init_order in range(1, order):

vec_t = timesteps[init_order].expand(x.shape[0])

x = self.multistep_dpm_solver_update(x, model_prev_list, t_prev_list, vec_t, init_order,

solver_type=solver_type)

if mask is not None and record_list is not None:

x = record_list[init_order - 1].to(device) * (1. - mask) + x * mask

model_prev_list.append(self.model_fn(x, vec_t))

t_prev_list.append(vec_t)

# Compute the remaining values by `order`-th order multistep DPM-Solver.

for step in range(order, steps + 1):

vec_t = timesteps[step].expand(x.shape[0])

if lower_order_final and steps < 15:

step_order = min(order, steps + 1 - step)

else:

step_order = order

x = self.multistep_dpm_solver_update(x, model_prev_list, t_prev_list, vec_t, step_order,

solver_type=solver_type)

if mask is not None and record_list is not None:

x = record_list[step - 1].to(device) * (1. - mask) + x * mask

for i in range(order - 1):

t_prev_list[i] = t_prev_list[i + 1]

model_prev_list[i] = model_prev_list[i + 1]

t_prev_list[-1] = vec_t

# We do not need to evaluate the final model value.

if step < steps:

model_prev_list[-1] = self.model_fn(x, vec_t)

elif method in ['singlestep', 'singlestep_fixed']:

if method == 'singlestep':

timesteps_outer, orders = self.get_orders_and_timesteps_for_singlestep_solver(steps=steps, order=order,

skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T,

t_0=t_0, device=device)

elif method == 'singlestep_fixed':

K = steps // order

orders = [order, ] * K

timesteps_outer = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T, t_0=t_0, N=K, device=device)

for i, order in enumerate(orders):

t_T_inner, t_0_inner = timesteps_outer[i], timesteps_outer[i + 1]

timesteps_inner = self.get_time_steps(skip_type=skip_type, t_T=t_T_inner.item(), t_0=t_0_inner.item(),

N=order, device=device)

lambda_inner = self.noise_schedule.marginal_lambda(timesteps_inner)

vec_s, vec_t = t_T_inner.tile(x.shape[0]), t_0_inner.tile(x.shape[0])

h = lambda_inner[-1] - lambda_inner[0]

r1 = None if order <= 1 else (lambda_inner[1] - lambda_inner[0]) / h

r2 = None if order <= 2 else (lambda_inner[2] - lambda_inner[0]) / h

x = self.singlestep_dpm_solver_update(x, vec_s, vec_t, order, solver_type=solver_type, r1=r1, r2=r2)

if denoise_to_zero:

x = self.denoise_to_zero_fn(x, torch.ones((x.shape[0],)).to(device) * t_0)

return x

https://github.com/Xiang-cd/DiffEdit-stable-diffusion

-

Why DDIM

With \(x_r\) being the encoded version of \(x_0\)(input image), using DDIM decoding on \(x_r\) unconditionally would give back the original image \(x_0\) as for the deterministic nature. In DiffEdit, we use DDIM decoding conditioned on the text query \(Q\), but there is still a strong bias to stay close to the original image. This is because the unconditional and conditional noise estimator networks \(\epsilon_θ\) and \(\epsilon_θ(·, Q)\) often produce similar estimates, yielding similar decoding behavior when initialized with the same starting point \(x_r\). This means that the edited image will have a small distance w.r.t. the input image, a property critical in the context of image editing.

Experiment and Benchmarks

The main goal is to modify only specific areas in an image according to a given prompt, without altering the rest of the image. This can be quite challenging because many existing methods result in undesired changes to the background while editing the main object. However, by using DiffEdit, we could easily achieve the goal through leveraging a combination of masking and DDIM encoding. Masking allows us to isolate the desired areas for modification, ensuring that the edits would remain confined to those regions. Meanwhile, DDIM encoding enables us to apply these changes within a latent space that encapsulates the full information of the original image. These two techniques, thus, ensures that the background remains largely unchanged compared to the input image.

The following experiments have been conducted by Couairon et al., 2022 [1] on three major datasets: ImageNet, Imagen, and COCO to compare the performance of DiffEdit with other models such as SDEdit. Latent diffusion models are used to perform these experiments. More specifically, they are the class-conditional model trained on ImageNet at resolution 256x256, and the Stable Diffusion model (890M parameter text-conditional model trained on LAION-5B). The resolutions of the masks for DiffEdit are 32x32 for ImageNet and 64x64 for both Imagen and COCO. The DDIM sampling is set to have 50 steps in addition to the encoding ratio parameter. Classifier-Free Guidance is also incorporated into the experiments with their recommended values for each of the two models.

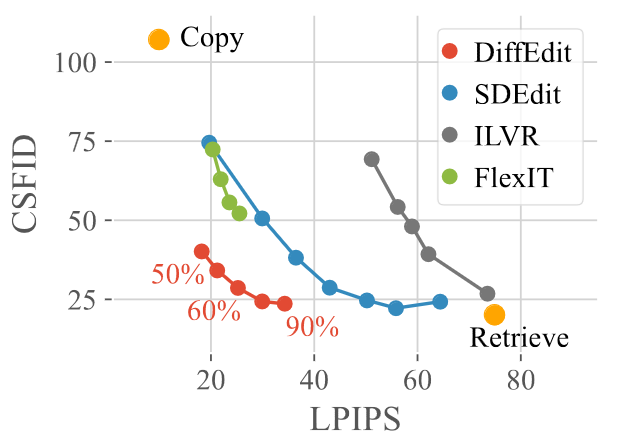

ImageNet

First, on ImageNet, the evaluation metrics are LPIPS (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity) and CSFID (Class-conditional FID). LPIPS measures the distance/similarity with the input image, while CSFID measures both image realism and consistency with respect to the query. For both metrics, lower values indicate better edits. It is worth noting that there is a tradeoff between the two metrics since better edits would generally improve the CSFID score as the edited images better represent the query while it also tends to deviate from the input, leading to worse LPIPS score.

Fig. 13 demonstrates the performances of several models. The two baseline cases are: 1) Copy (best LPIPS score of 0 by just copying the input image), and 2) Retrieve (best CSFID score by just replacing the input with an image of the targeted class from the ImageNet dataset). It can be observed that while both SDEdit and ILVR have CSFID values similar to that of the Retrieval baseline, among the diffusion-based methods, DiffEdit has achieved a similar CSFID score and a significantly lower LPIPS score across different encoding ratios indicated by the red numbers. On the other hand, FlexIT, which is a mask-free, optimization-based model using VQGAN and CLIP, obtains both higher LPIPS and higher CSFID scores, indicating its incapability in producing relatively realistic images.

Figure 13. Comparison of DiffEdit with other models on ImageNet. [1]

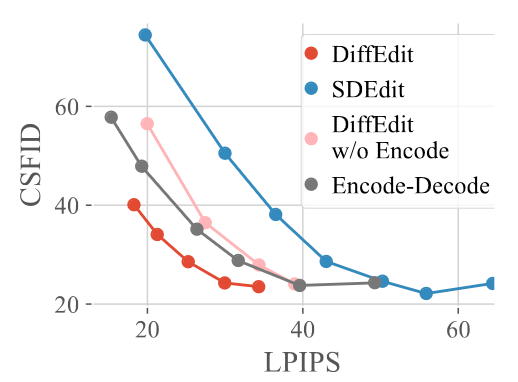

Fig. 14 further shows how masking and DDIM encoding enhance DiffEdit’s performance on the specific task. Four models are being compared here: 1) DiffEdit, 2) Encode-Decode with DDIM encoding added but has no masking, 3) DiffEdit without DDIM encode but has masking, and 4) SDEdit, which has neither DDIM encoding nor masking. It can be observed from the graph that either adding the DDIM encoding (indicated by the grey line) or adding the masking (indicated by the pink line) helps improve the LPIPS-CSFID tradeoff since they are closer to the origin. In addition, combining both methods (indicated by the red line, i.e. the actual DiffEdit model) gives an even better tradeoff as the background is better preserved by masking while the visual information inside the mask is better preserved by DDIM encoding.

Figure 14. Comparing the contribution of masking and DDIM Encoding. [1]

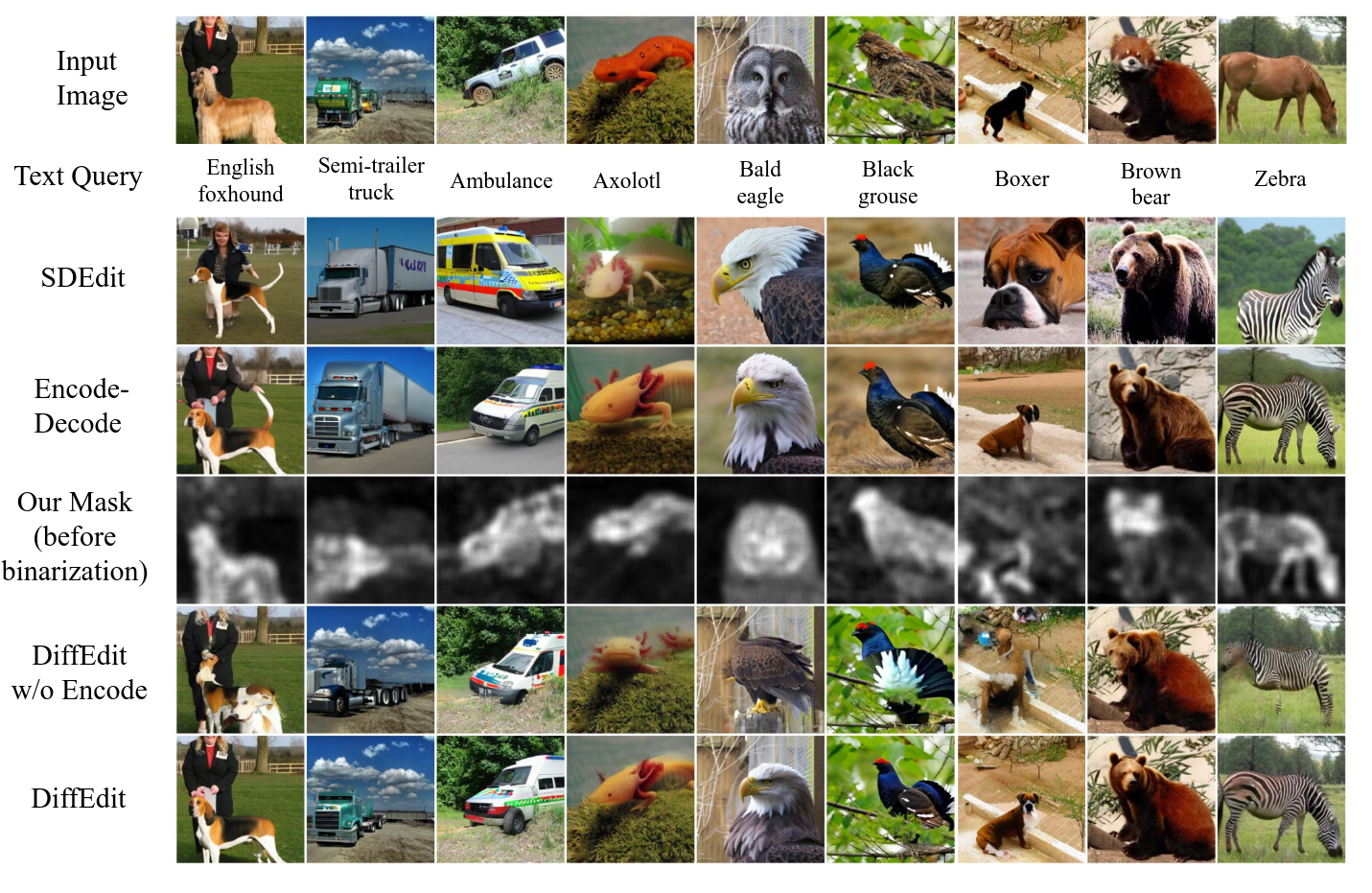

Fig. 15 shows a more straightforward comparison between DiffEdit and other models. By inspecting the output generated by those models, one could make the following observations: when masking is absent (i.e. SDEdit and Encode-Decode), the backgrounds have been modified significantly compared to the input, which is an undesired bahavior of our task; when DDIM encoding is absent (i.e. SDEdit and DiffEdit without Encode), visual information from the input has not been preserved and demonstrated correctly on the output. But when both techniques are used, DiffEdit has nicely replaced the desired area in the input image with the new object indicated by the text query while the background remains almost identical to that of each input.

Figure 15. Comparison of images generated by different models with input from the ImageNet dataset. [1]

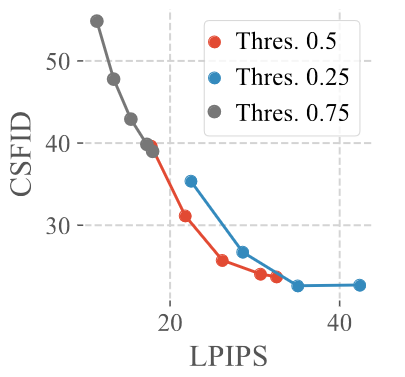

Another ablation experiment that has been conducted is related to the testing of different mask binarization threholds. The threhold is used to determine how a continuous mask is converted to a binary mask. Fig. 16 shows that compared to the default value of 0.5, a lower threshold of 0.25 results in a larger mask, more image modifications, and therefore worse tradeoffs. A higher threshold of 0.75, on the other hand, results in smaller masks that are too restrictive, preventing the CSFID score from decreasing further.

Figure 16. Comparison of mask binarization threshold on ImageNet. [1]

Imagen

The next set of testings involves background alterations, substitution of secondary objects, and adjustments to object attributes. Since Imagen is known for its compositional abilities by using templated prompts to generate images, it is used as the testing subject in this case. More specifically, 300 prompts were generated and later modified in a way where one of the elements of each prompt is changed.

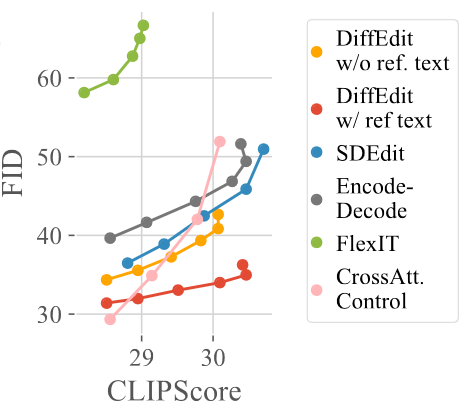

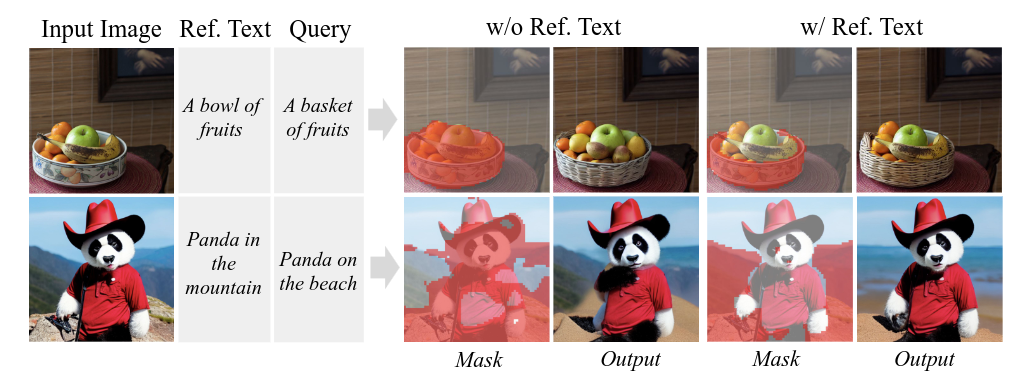

Instead of CSFID, FID is used as a metric to evaluate model performance in addition to the CLIPScore in this case to assess realism and prompt-output alignment, respectively. Fig. 17 reveals that DiffEdit outperformed other methods such as SDEdit, FlexIT, and Cross Attention Control in the precision of edits by integrating masking with DDIM encoding. Moreover, two types of DiffEdit were evaluated based on different mask computation methods: one using the original caption (DiffEdit w/ ref.text) and the other using blank text (DiffEdit w/o ref.text). To view the difference more directly, one could refer to Fig. 18. Notice that when reference text is used, the common parts between the reference text and the query are not included in the mask anymore (such as the fruits in the first exmaple and the panda in the second example). But when reference text is absent, the mask becomes less precise, potentially worsening the performance of the model. According to Fig. 17, DiffEdit w/ ref.text achieves the best tradeoff between FID and CLIPScore among all the tested models.

Figure 17. Comparison of DiffEdit with other models on Imagen. [1]

Figure 18. Effect of reference text on DiffEdit masks and edits. [1]

COCO

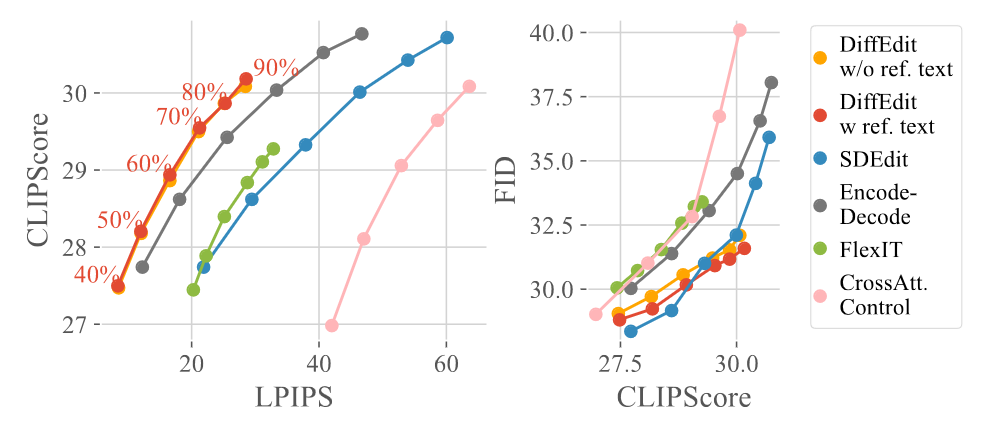

In order to test with more complex prompts, the study has used images and captions from the COCO dataset, particularly focusing on annotations that associate images with captions similar to the original but contradict the depicted scene. Similarly, the models are evaluated with CLIPScore, FID, and LPIPS as the metrics in this case. Fig. 19 shows that DiffEdit outperforms other models in the CLIP-LPIPS tradeoff, though it achieves a lower maximum CLIP score compared to SDEdit. FID scores for DiffEdit also show significant improvement over most of the other models. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that in contrast to the results obtained on the Imagen dataset, DiffEdit w/ ref.text and DiffEdit w/o ref.text achieve comparable results in this case. The reason behind this is that the captions often describe the original image in a different way than the query text, which makes it harder to precisely select the areas that needed to be edited in an image.

Figure 19. Comparison of DiffEdit with other models on COCO. [1]

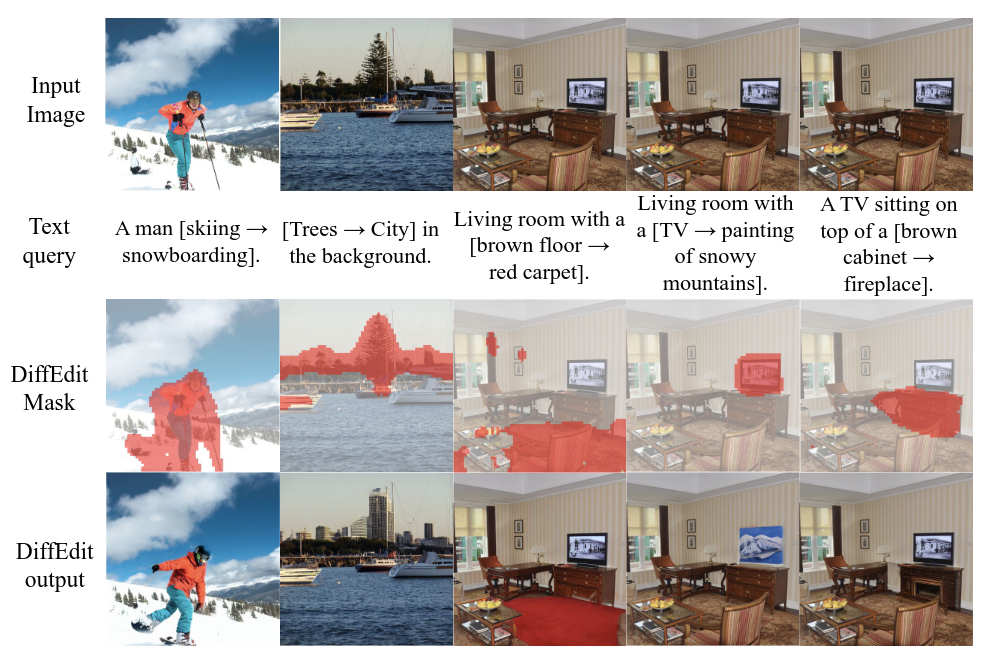

Fig. 20 shows how DiffEdit performs on the COCO dataset in a qualitative way. One can also notice how different queries would result in different objects to be modified given the same input image from the COCO dataset.

Figure 20. Results obtained using DiffEdit on COCO. [1]

Our Ideas

End-to-End Generation and Editing

By seamlessly integrating DiffEdit with BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training) and other state-of-the-art text-to-image models (Stable Diffusion Model), we’ve developed a comprehensive, end-to-end generation and editing pipeline tailored to enhance user creativity and streamline the image creation process.

At the core of our framework is the flexibility it offers users. They can initiate the creative process in two distinct ways: either by generating an image from scratch using a descriptive prompt through stable diffusion models or by uploading a local image as a starting point. This dual-pathway approach ensures that users from various backgrounds and with differing levels of expertise can easily engage with our system.

Once the initial image is selected or created, our system introduces the editing capability. Users can specify the desired modifications to the image using a simple text prompt, outlining the changes they envision for the target image. The system then generates a preview of the mask, a visual representation of the areas to be edited, based on the provided prompt. This step is crucial as it offers users the opportunity to review and confirm that the mask aligns with their expectations before proceeding, ensuring a high degree of satisfaction with the final output.

Upon user approval of the mask, our framework employs DiffEdit to execute the specified edits. Leveraging the target prompt and the approved mask, DiffEdit intricately alters the image to reflect the requested changes, generating the final edited image. A unique feature of our framework is the integration of the BLIP model, which introduces the option for image-to-text conversion. This means that users can opt to generate a source prompt for their images automatically, making the process more accessible and reducing the need for manual input. This feature is particularly beneficial for users who may struggle to articulate their vision in a text prompt or wish to explore creative directions suggested by the model’s interpretation of the image.

Text Guided Diffusion Based Object Segmentation

Our innovative concept, “Text-Guided Diffusion-Based Object Segmentation,” harnesses the sophisticated capabilities of DiffEdit for generating precise masks, and repurposes this functionality towards achieving advanced text-guided object segmentation.

At the heart of this process is a novel utilization of DiffEdit’s mask generation feature, which we adapt for the purpose of segmenting objects from images based purely on textual descriptions. The workflow begins by taking a descriptive prompt for the object intended to be segmented (the object prompt). This prompt is then intelligently compared with a source prompt generated by BLIP (Bidirectional Language-Image Pre-training) model, which effectively describes the entire image. Our system strategically removes the object’s text from this source prompt (by replacing it with the token [None]), creating what we term the “target prompt.”

Subsequently, we initiate the mask generation process. Leveraging the initial image, the comprehensive source prompt, and the meticulously crafted target prompt (from which the object text has been excluded), our system embarks on generating a mask. The underlying theory is that the absence of the target object’s text in the target prompt compels the predictive model to focus the differential noise, essentially the areas of discrepancy, on the target object. This concentrated discrepancy illuminates the target object, enabling the extraction of a highly accurate segmentation mask.

This method is intuitive because it mirrors human reasoning by excluding the target object from the textual description of the scene, prompting the model to isolate and highlight the object of interest. It is innovative because it repurposes the inherent capabilities of DiffEdit for a novel application, extending its utility beyond mere image editing to sophisticated segmentation tasks.

The significant implication of our “Text-Guided Diffusion-Based Object Segmentation” approach lies in its ability to sidestep the traditionally resource-intensive process of training specialized models for object segmentation. Instead of dedicating vast amounts of computational resources and time to train models specifically for segmentation tasks, we leverage the sophisticated text-image understanding capabilities inherent in pre-trained diffusion models. This strategy enables us to essentially get a “free ride” on the segmentation capability, exploiting the model’s existing skills in a novel and efficient manner.

Demo

You can clone the Github Repo to have a try

git clone https://github.com/JackHe313/InteractiveDiffEdit.git

cd InteractiveDiffEdit

pip install --upgrade pip

pip install -r requirements.txt

usage:

Python diffEdit.py [--img_url IMG_URL] --target_prompt TARGET_PROMPT [--source_prompt SOURCE_PROMPT] [--save_path SAVE_PATH] [--device DEVICE] [--seg_prompt SEG_PROMPT] [--seed SEED]

For End-to-End Image Generation Editing:

User uploaded Image Editing Example

python diffEdit.py -i "https://github.com/Xiang-cd/DiffEdit-stable-diffusion/raw/main/assets/origin.png" -t "a bowl of pears"

In which case the program will generate the mask and ask about your satisfaction about it. When user accepts the mask, it will edit the image based on the target prompt. The demo is shown in Fig. 21.

Figure 21. End-to-End Image Generation Editing Demo.

User Generate Image Editing Example

python diffEdit.py -p "a bowl of fruits"

This time instead of providing the image, we generate the image based on Stable Diffusion first. Given the prompt, it will display a generated image and if user are not satisfied, it will ask for the prompt for changes and do editing as the above process.

For Text based Object Segmentation

python diffEdit.py -i "https://github.com/Xiang-cd/DiffEdit-stable-diffusion/raw/main/assets/origin.png" -sp -t "fruit"

It will generate the mask(segmentation, shown in Fig. 22) correspond with the target prompt.

Figure 22. Text-base-Object-Segmentation.

All Options:

-h, --help show this help message and exit

--img_url IMG_URL, -i IMG_URL

URL of the image to edit.

--target_prompt TARGET_PROMPT, -t TARGET_PROMPT

Prompt for the target image.

--source_prompt SOURCE_PROMPT, -p SOURCE_PROMPT

Optional prompt for the source image.

--save_path SAVE_PATH, -s SAVE_PATH

Optional path to save the edited image.

--device DEVICE, -d DEVICE

Device to run the model on.

--seg_prompt, -sp Boolean flag to indicate if the target_prompt is a segment prompt.

--seed SEED Seed for the random number generator.

Further Works

-

Benchmarking and Evaluation: Conduct a comprehensive benchmark study to evaluate the accuracy and efficiency of the segmentation method against traditional and contemporary image segmentation and editing models, including quantitative metrics such as Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, recall.

-

Explore Different Diffusion Model’s impact on the segmentation capability Conduct a systematic comparison of various diffusion models on the result of the accuracy for the segmentation results.

Ethics Impact

The ethics surrounding image editing diffusion models are multifaceted, involving considerations of privacy, consent, misinformation, and societal impact. As these models become more sophisticated and widely accessible, they pose both opportunities and challenges.

Consent and Privacy

- Misuse of Personal Images: There’s a risk of personal images being edited or manipulated without consent, leading to privacy violations. This includes generating realistic images of individuals in scenarios they were never in, which could harm reputations or lead to personal distress.

- Deepfakes: The creation of convincing fake videos or images of individuals saying or doing things they never did. This poses significant risks in the context of misinformation, blackmail, or personal attacks.

Misinformation and Trust

- Spreading Falsehoods: The ability to create realistic images from textual descriptions can be used to generate fake news, misleading content, or historical revisionism. This undermines trust in media and can have real-world consequences by influencing public opinion or election outcomes.

- Erosion of Trust: As it becomes easier to create believable fake images, the public’s trust in digital content and media could erode, leading to a “reality apathy” where people become more skeptical of all information, including legitimate content.

Societal and Cultural Impact

- Bias and Stereotypes: Like any AI technology, image editing diffusion models can perpetuate or even exacerbate biases present in their training data, reinforcing stereotypes or underrepresenting marginalized groups.

- Impact on Art and Culture: These models could democratize artistic expression, enabling more people to create art or visualize concepts. However, there’s also a risk they could dilute the value of human creativity or homogenize cultural outputs.

Ethical Frameworks and Solutions

To address these ethical concerns, stakeholders (including developers, users, and policymakers) need to collaborate on developing ethical frameworks, guidelines, and regulations that balance innovation with ethical considerations.

- Transparency: Clear labeling of AI-generated content to distinguish it from human-created content.

- Consent and Privacy Protections: Mechanisms to ensure images of individuals are used ethically, with consent, and with respect for privacy.

- Regulation and Oversight: Legal and regulatory frameworks that govern the use of these technologies, including copyright protections and measures against misinformation.

- Bias Mitigation: Efforts to identify and mitigate biases in training data and model outputs, ensuring fair and equitable representation.

In conclusion, while image editing diffusion models hold tremendous potential for creativity, communication, and innovation, their ethical implications necessitate careful consideration and proactive management. Balancing the benefits of these technologies against their risks is crucial to ensuring they contribute positively to society.

Conclusion

We discuss DiffEdit, a novel algorithm for semantic image editing based on diffusion models. Given a textual query, using the diffusion model, DiffEdit infers the relevant regions to be edited rather than requiring a user generated mask. Furthermore, in contrast to other diffusion-based methods, DiffEdit initialize the generation process with a DDIM encoding of the input. We introduce the theoretical analysis that motivates this choice, and demonstrate the experiments that this approach conserves more appearance information from the input image, leading to lighter edits. Quantitative and qualitative evaluations on ImageNet, COCO, and images generated by Imagen, show that this approach leads excellent edits, improving over previous approaches.

Reference

[1] Guillaume Couairon, Jakob Verbeek, Holger Schwenk, and Matthieu Cord. DiffEdit: Diffusion-based semantic image editing with mask guidance. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2210.11427, 2022.

[2] Jiahui Yu, Zhe Lin, Jimei Yang, Xiaohui Shen, Xin Lu, and Thomas S Huang. Generative image inpainting with contextual attention. In CVPR, 2018.

[3] Yongcheng Jing, Yezhou Yang, Zunlei Feng, Jingwen Ye, Yizhou Yu, and Mingli Song. Neural style transfer: A review. Transactions on visualization and computer graphics, 26(11):3365-3385, 2019.

[4] William A. Barrett and Alan S. Cheney. Object-Based Image Editing. https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/cse590b/02au/barrett_high_res.pdf, 2022.

[5] Bowen Li, Xiaojuan Qi, Philip HS Torr, and Thomas Lukasiewicz. Image-to-image translation with text guidance. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2002.05235, 2020b.

[6] Katherine Crowson, Stella Biderman, Daniel Kornis, Dashiell Stander, Eric Hallahan, Louis Castricato, and Edward Raff. VQGAN-CLIP: Open domain image generation and editing with natural language guidance. In ECCV, 2022.

[7] Gwanghyun Kim and Jong Chul Ye. DiffusionCLIP: Text-guided image manipulation using diffusion models. In CVPR, 2021.

[8] Jooyoung Choi, Sungwon Kim, Yonghyun Jeong, Youngjune Gwon, and Sungroh Yoon. ILVR: Conditioning method for denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In ICCV, 2021.

[9] Chenlin Meng, Yutong He, Yang Song, Jiaming Song, Jiajun Wu, Jun-Yan Zhu, and Stefano Ermon. SDEdit: Guided image synthesis and editing with stochastic differential equations. In ICLR, 2021.

[10] Jiaming Song, Chenlin Meng, and Stefano Ermon. Denoising diffusion implicit models. In ICLR, 2021.

[11] Jonathan Ho and Tim Salimans. Classifier-Free Diffusion Guidance. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2207.12598, 2022.

[12] Lilian Weng. What are diffusion models?. Lil’Log. https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2021-07-11-diffusion-models/#speed-up-diffusion-model-sampling, 2021.