Galaxy Morphology

In this Blog, we will take a look at how Deep Learning impacted the Astronomy community with deep representation learning. It’s interesting to recognize that transferring the learned representations from a different dataset to other unseen related-tasks is more effective than starting to learn everything from scratch! These tasks for astronomers include identifying galaxies with similar morphology to a query galaxy, detecting interesting anomalies, and adapting models to new tasks with only a small number of newly labeled galaxies. In this post, we will share our own results and insights about a paper “Practical Galaxy Morphology Tools from Deep Supervised Representation Learning” and their contributions that, even to our days, are still very meaningful to understanding Neural Networks (7 min read)

Introduction

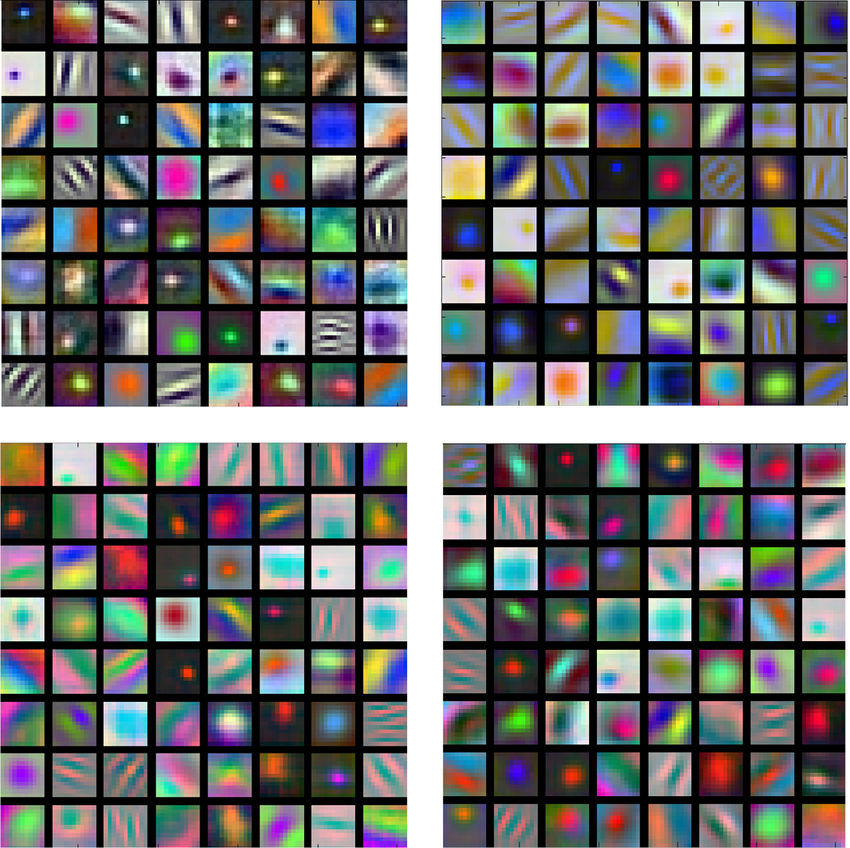

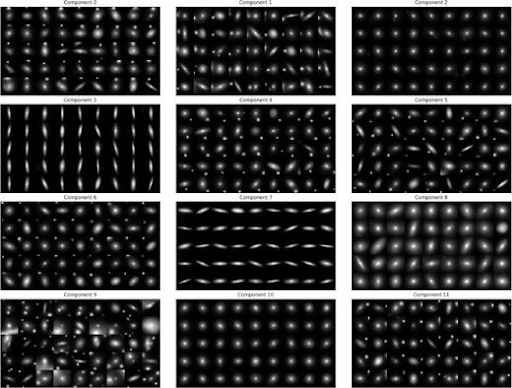

Representation learning algorithms in machine learning are designed to extract meaningful patterns from raw data, generating representations that are more interpretable and computationally efficient. This is especially beneficial for handling high-dimensional data like images and text, improving the training process and our comprehension of the model’s learned features (see Fig. 1). In the realm of astronomy, image representations play a crucial role in various practical applications. An image representation function transforms high-dimensional image data into a lower-dimensional vector form, simplifying the definition of a meaningful distance metric (e.g., Manhattan Distance, Euclidean, etc.). Within this representation space, similar images are positioned closer together, with slight image variations corresponding to minor changes in the representation, and vice versa.

Fig 1. Visualization of the output of the first convolutional layers of popular convolutional Architectures. We can see that these first layers are extracting patterns related to straight lines in different directions [2].

One of the significant challenges in astronomy stems from the abundance of unlabeled data, often in the millions, collected from sky surveys conducted by observatories and telescopes such as Gemini South in Chile, WIYN on Kitt Peak in Arizona, and the Hubble in low-Earth orbit. The sheer volume of these data streams makes manual processing nearly impractical. Moreover, given the vastness of the cosmos, there likely exist numerous undiscovered phenomena and types of galaxies yet to be observed. When it comes to discovering new galaxies, it is essential to map them in a manner that aids researchers in prioritizing their investigations and establishes a taxonomy of galaxies based on interpretable physical attributes. Relying solely on an unsupervised data-driven approach may yield quicker results but may sacrifice interpretability, which is crucial in the scientific methodology inherent in astronomy research.

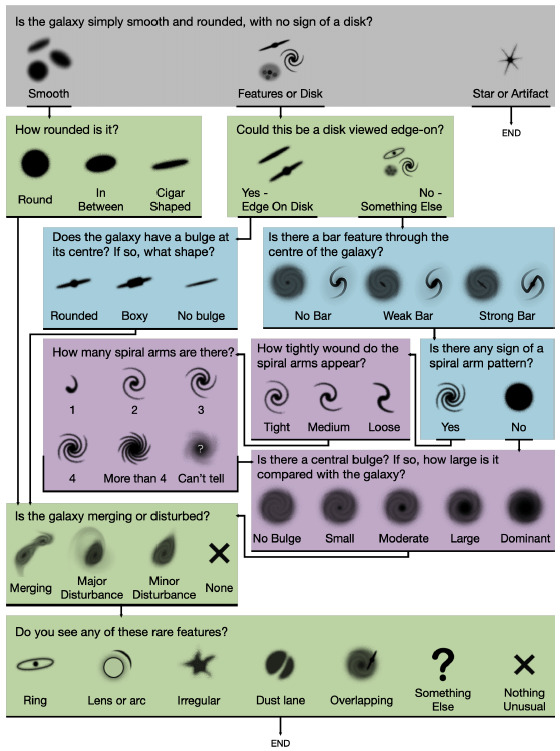

Therefore, initiatives like the Galaxy Zoo project, initiated in 2007 [3], tackle these challenges by harnessing crowdsourcing and input from citizen scientists to achieve consensus labeling and classify galaxies. Participants are tasked with simple questions to determine whether observed galaxies are elliptical, mergers, spirals, or exhibit unusual structural patterns (refer to Fig. 2). In this post, we will delve into how computer scientists and astronomers have benefited from extensive collaboration with the public and the interpretable automation provided by artificial intelligence.

Fig 2. Classification decision tree for GZD-5, with new icons as shown to volunteers [3].

Insights from Earlier Approaches

Let’s explore the approaches that researchers have employed in the past. While these methods were developed around the 2020s, we acknowledge that in the computer vision community, solutions developed just one year ago are already considered outdated in this fast-paced, dynamic research environment. However, they still offer valuable insights into the methodologies used to address and refine solutions for this field.

Deep Representation Learning

The article “Practical Galaxy Morphology Tools from Deep Supervised Representation Learning” [1] proposes a methodology to provide astronomers with a roadmap for studying the cosmos based on deep learning. To help the community benefit from their pretrained models, the authors release much of the code from this work as the documented Python package ‘zoobot’. They proposed several practical tasks that are handy when studying the universe, stemming from their deep learning approach and pretrained models.

-

The first practical task is a similarity search method (see Fig. 3). Similarity searches aim to retrieve the most similar galaxies to a query galaxy. To achieve this, they require a quantified measurement of the similarity between two galaxies—a problem underlying the search for automatic taxonomies of galaxies. Since their representation arranges galaxies by similarity, their measurement of similarity is simply estimated as the distance in the representation space between galaxies. The most similar galaxies are the query galaxy’s nearest neighbors.

-

The second practical task was finding rare galaxies that were personally interesting to a given user. They used Gaussian Process regression to model user interest and the uncertainty about that interest for each galaxy. They selected which galaxies to be rated for interest by the user with active learning and a Bayesian optimization acquisition function. This feature is crucial because it allows for the identification of rare and interesting galaxies that might otherwise be overlooked.

-

The third practical task was fine-tuning a convolutional neural network to solve a new galaxy classification task, specifically, to find ringed galaxies in DECaLS (new task). They trained the same architecture in three ways: from scratch, fine-tuned from ImageNet, and fine-tuned from Galaxy Zoo DECaLS.

Nowadays, transfer learning has become a powerful tool that has helped the NLP community to widely disseminate the contributions of large language models across different fields and levels of research and production. This article shares a similar philosophy, clearly stating their openness to helping researchers build upon one another’s models rather than creating them from scratch for each new problem.

Fig 3. Visualisation of the representation learned by the CNN proposed in [1], showing similar galaxies occupying similar regions of feature space. Created using Incremental PCA and umap to compress the representation to 2D, and then placing galaxy thumbnails at the 2D location of the corresponding galaxy based on a similarity search.

AstroVaDEr

To not depend on human-assigned labels, AstroVaDEr: an astronomical variational deep embedder, introduces a VAE designed to perform unsupervised clustering and synthetic image generation using astronomical imaging catalogs [5]. This model is a CNN that learns to embed images into a low-dimensional latent space while also optimizing a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to cluster the training data. Using this approach, we can use the learned GMM to show how many galaxies are assigned to each cluster label based on their highest probability component. To help prevent overfitting and augment the data set, images are randomly flipped on their horizontal/vertical axes each time they are fed into the network. Additionally, they convert the image to a greyscale, which during training time ensures that the network is learning strictly based on morphology, rather than learning the color dependence of different morphological types.

For AstroVaDEr, they choose to implement the VaDE algorithm [6] with the optimizations from Stable Variational Deep Clustering (s3VDC). VaDE calculates a single encoded mean and variance for each sample and learns the GMM means, variances, and weights as trainable parameters. They chose the optimum number of clusters to fit the data by initializing many instances of a BGM with different mini-batches of embedded samples and found that 12 clusters emerged as a fairly consistent mixture configuration. Compared to the other methods discussed here, using this stick-breaking method is computationally fast, consistent, intuitive, and crucially doesn’t require comparing clustering metrics and visualizations of a dozen fitted models where the best options aren’t immediately apparent

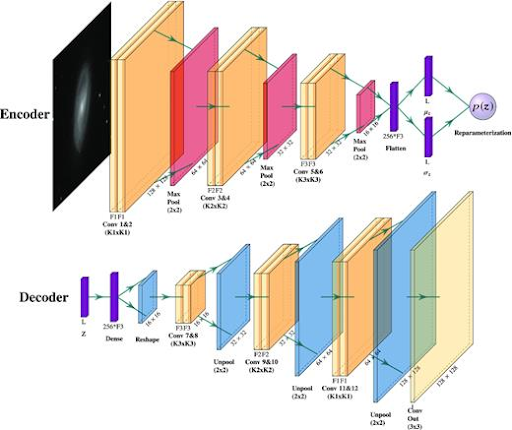

The AstroVaDEr architecture is shown below (see Fig. 3), intended to be flexible and based on the CNN for GZ2. The final upsampled output is fed into a final convolutional layer with either a single filter for grey-scale input or three filters for RGB images. Throughout the network, they implement the Leaky ReLU activation function, and the network is optimized using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate that decreases every five epochs using exponential decay.

Fig 3. Network architecture representation of AstroVaDEr [5]

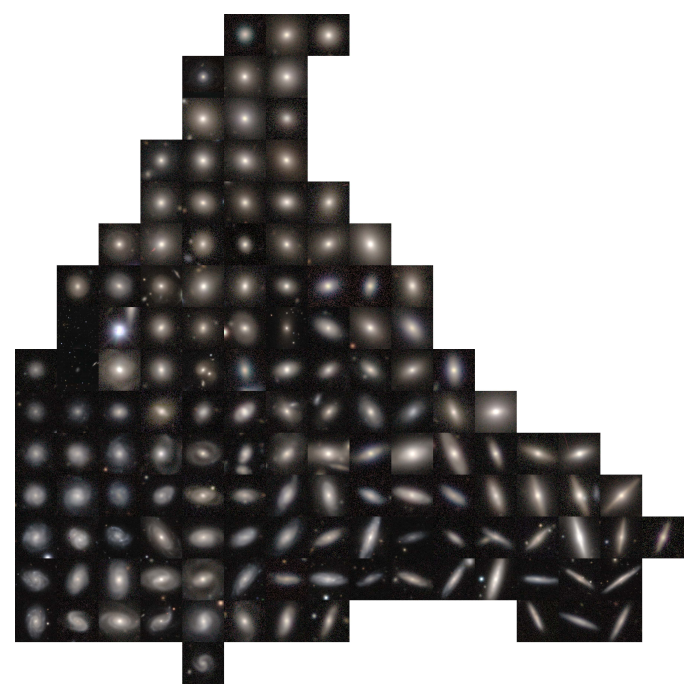

We observe the following unsupervised clustering results using the AstroVaDEr model (see Fig. 4). It shows the image reconstructions of test data objects assigned to each cluster. This figure shows the objects with the highest cluster likelihood of objects from those that have the appropriate cluster label. Images are shown with a linear scale and pixel range of (0,1).

Fig 4. Image reconstructions of test data objects assigned to each cluster [5]

This approach found their unsupervised generative model clustered galaxies according to whether they have a background/secondary partner galaxy in the top or bottom corner of the image [1]. The benefits of this approach include its scalability and adaptability, which enable it to handle larger datasets or different types of imaging data effectively. The model’s generative capabilities can produce realistic synthetic galaxy images based on its classification system. Although the clustering outcomes may diverge from human expectations, they provide a logical framework for assessing galaxy morphology. Additionally, these results offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of unsupervised clustering for morphological features, guiding future enhancements in these techniques.

However, there are challenges. For example, if we have six clusters predominantly consisting of objects with less than two secondary sources, AstroVaDEr doesn’t distinguish based on the primary source’s morphology but rather on the secondary sources’ placement. This underscores the value of human judgment, especially since the model sometimes overemphasizes the presence of companion objects. Moreover, when the batch size exceeds a certain threshold, the network may fail to prepare batches quickly enough for efficient GPU processing. All in all, we conclude that AstroVaDEr unexpectedly places high importance on the presence of companion objects – demonstrating the importance of human interpretation.

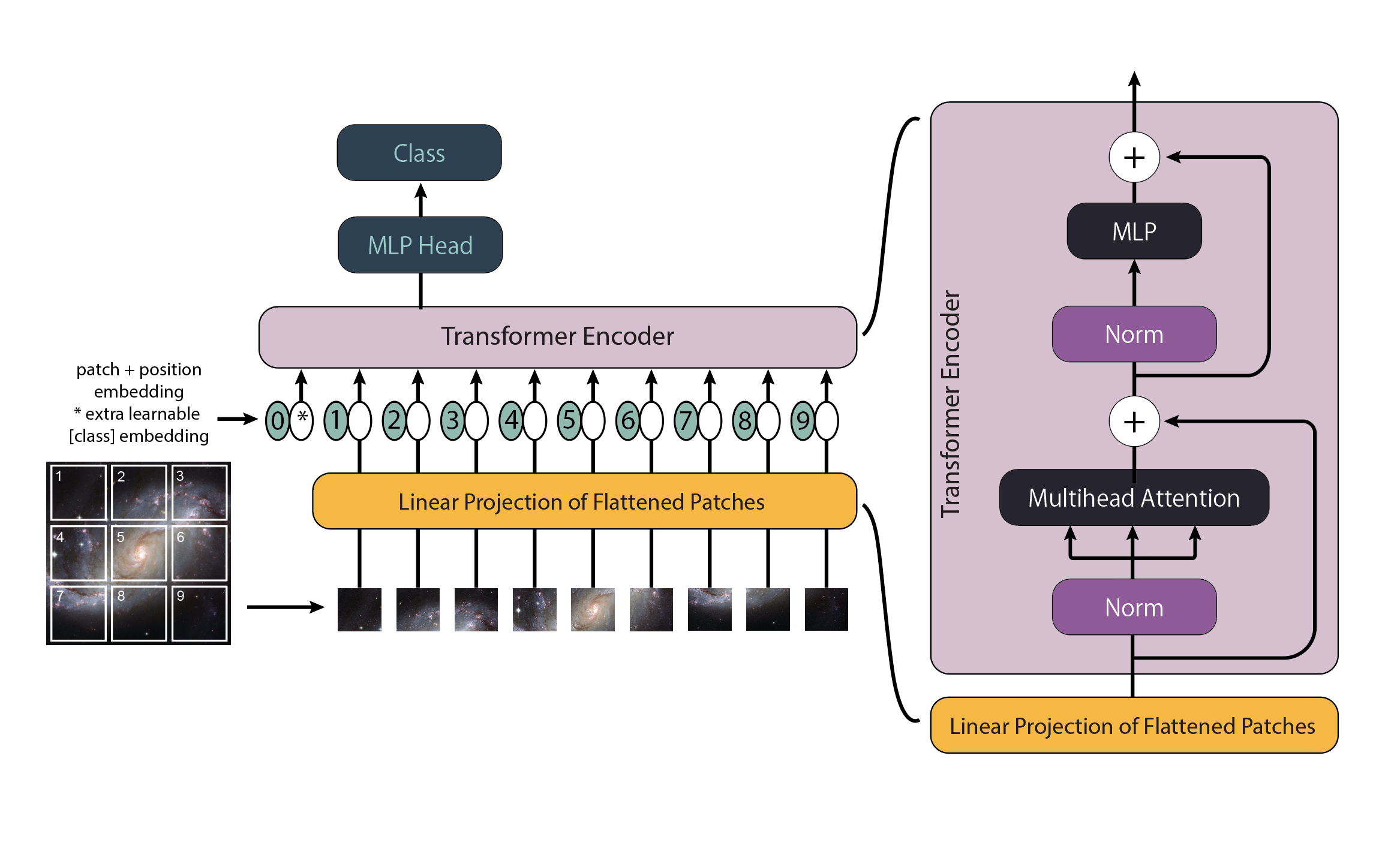

Vision Transformers

A glance at the state-of-the-art models reveals, as expected, that Vision Transformers (ViTs) have been included in the efforts to classify galaxies [7]. Transformers, in general, are more scalable with massive amounts of data, such as in this case. ViTs have been shown to scale exceptionally well as the amount of training data increases, thanks to their self-attention mechanism (see Fig. 4) and lack of convolutional inductive biases compared to their older cousin, the CNN. This makes them attractive for leveraging the vast quantities of unlabeled galaxy images from surveys.

Fig 4. The architecture overview of a Vision Transformer adapted for astronomy [7].

Promising initial results have been demonstrated by applying Linformer [7] for the task of galaxy morphological classification. These ViT models 1) achieve competitive results compared to state-of-the-art CNNs, 2) reach more balanced categorical accuracy compared with previous works by applying tuned class weights in the loss function during training, and 3) perform specifically well in classifying smaller-sized and fainter galaxies. ViTs achieve higher classification accuracy for smaller and fainter galaxies, which are more challenging to classify due to noisier image quality. Since cosmic images exhibit limited diversity in features and are nearly indistinguishable except for the central galaxy, this observation suggests that Vision Transformers (ViTs) may demonstrate greater robustness towards difficult or blurred images, with their attention matrices potentially learning this fundamental pattern within the dataset.

Apart from supervised learning, Vision Transformers offer numerous potential applications that could significantly benefit future astronomical surveys. One such application is the utilization of self-supervised learning techniques, such as ViT DINO [8], to automate the classification of images. Additionally, Vision Transformers hold promise in potentially improving anomaly detection capabilities within astronomical datasets.

Looking ahead, the Rubin Observatory LSST is poised to generate an unprecedented volume of galaxy images, showcasing a remarkable sensitivity that enables the observation of galaxies ten orders of magnitude fainter than those in existing datasets like Galaxy Zoo 2. ViTs’ demonstrated capabilities in handling large datasets and their resilience to image noise highlight their potential significance in analyzing astronomical images in this data-rich era. This advancement not only aids in understanding the physics of galaxies but also paves the way for deeper insights into the universe’s intricacies.

Bonus

Running the Existing Codebase

Notebook can be found here: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1bE4KLPQApzIES9TNDv-r-FLwSINubxcx?usp=sharing

We used Github’s provided quickstart guide to install Zoobot, download the datasets, use their custom GalaxyDataModule, and fine tune it on some data for a binary classification task. In particular, the data was the “Demo Ring Dataset” - a small dataset of only 1000 galaxies labeled as ring galaxies or non-ring galaxies. The results from this quickstart pipeline provided these labeled images showing the model’s predictions.

Fig 6. Labelled Ring Predictions: Example of what the quickstart guide outputs as labelled image predictions [6].

Implementing Own Idea

Our second notebook can be found here: https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1Pn8xqEQ0UC1rXGIebt82LUhaafl2rWiA?usp=sharing

In this notebook, we investigated how we could modify the quickstart guide in a meaningful way. Initially, we wondered if we could optimize the model in some way, like by changing the activation functions or the optimizer, but since that code was abstracted away by the GalaxyDataModule module of their Zoobot library, we instead chose to modify the quickstart by training on a different task on a different dataset.

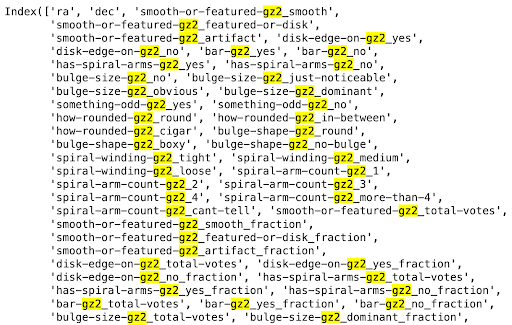

In particular, we trained on the GZ2 dataset which had many columns (only some are shown below), which was challenging to understand. GZ2 also has many more images at around 210K.

Fig 7. GZ2 Column Names: A sample of the data columns of the GZ2 Dataset [7].

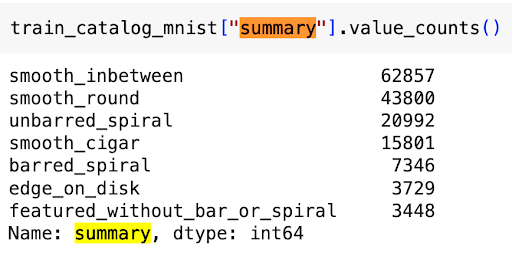

Eventually though we realized that there was a “summary” column which we used as our multi-class classification target labels.

Fig 8. GZ2 Label Counts: The class counts across the entire GZ2 Dataset [8].

After cleaning the data, dropping unnecessary columns, and modifying the model architecture to work for this new problem, we were able to plot predicted-labels for unseen images as below.

Fig 9. MultiClassification Task Output: Sample model output on unseen data [9].

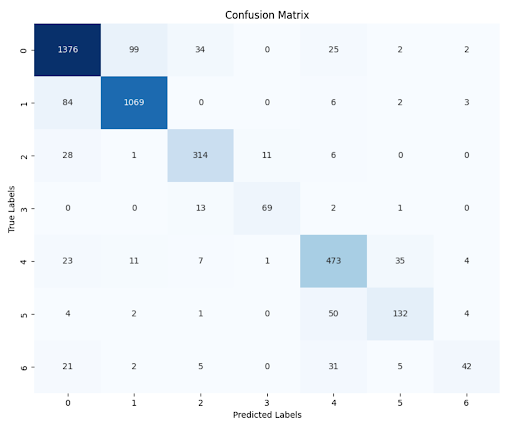

Lastly, we made a confusion matrix to better quantify the success of the model.

Fig 9. MultiClassification Confusion Matrix: Visual representation of multiclassification model effectiveness [10].

References

[1] Walmsley, et al. “Practical Galaxy Morphology Tools from Deep Supervised Representation Learning”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.12735. 2022.

[2] Asano, et al. “Self-labelling via simultaneous clustering and representation learning”. https://arxiv.org/abs/1911.05371. 2019.

[3] Chris J. Lintott, et al. “Galaxy Zoo: morphologies derived from visual inspection of galaxies from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 389, Issue 3, September 2008, Pages 1179–1189, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13689.x

[4] Mike Walmsley, et al. “Galaxy Zoo DECaLS: Detailed visual morphology measurements from volunteers and deep learning for 314 000 galaxies”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 509, Issue 3, January 2022, Pages 3966–3988, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stab2093

[5] Spindler A., Geach J. E., Smith M. J., 2020. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 502, Issue 1, March 2021, Pages 985–1007, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/staa3670

[6] Jiang Z., Zheng Y., Tan H., Tang B., Zhou H., 2016, preprint (arXiv:1611.05148)

[7] Joshua Yao-Yu Lin, et a. “Galaxy Morphological Classification with Efficient Vision Transformer” (NeurIPS 2021).

[8] Mathilde Caron, et. al. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.14294, 2021.