Deep Neural Networks for Facial Recognition

Facial recognition is the technology of identifying human beings by analyzing their faces from pictures, video footage or in real time. Facial recognition has been an issue for computer vision until recently. The introduction of deep learning techniques which are able to grasp big data faces and analyze rich and complex images of faces has made this easier, enabling new technology to be efficient and later become even better than human vision in facial recognition.

- Table of contents

- Introduction

Table of contents

Introduction

Facial recognition is the technology of identifying human beings by analyzing their faces from pictures, video footage or in real time. Facial recognition has been an issue for computer vision until recently. The introduction of deep learning techniques which are able to grasp big data faces and analyze rich and complex images of faces has made this easier, enabling new technology to be efficient and later become even better than human vision in facial recognition.

Why do we care about facial recognition?

Facial recognition has gained significant attention and relevance in today’s digital landscape due to its multifaceted applications and implications across various domains. From enhancing security measures to streamlining user authentication processes, facial recognition provides unparalleled convenience and efficiency. We can see facial recognition integrated in law enforcement, retail, healthcare, and even social media platforms. This highlights its versatility and potential to revolutionize how we interact with technology and each other.

Face recognition tasks

These are the most important tasks in face recognition:

-

Face Matching: find the best match for a given face

-

Face Similarity: find faces that are most similar to a given face

-

Face Transformation: generate new faces that are similar to a given face

-

Face Verification: a one-to-one mapping of a given face against a known identity (e.g. is this the person?)

-

Face Identification: a one-to-many mapping for a given face against a database of known faces (e.g. who is this person?)

Why is facial recognition a difficult task?

Facial recognition proves to be a complex task due to the variety of factors involved in real-world scenarios. These include the variability of face angles, expressions, lighting conditions, and even aging effects. A common challenge arises from the clarity of images. When images lack clarity, facial features become less discernible, leading to increased pixelation. As a result, deep learning algorithms require higher resolution input images to accurately identify and analyze facial characteristics.

Current state-of-the-art approaches for this task require annotation of facial landmarks or annotation of face poses. They also require training dozens of models to fully capture faces in all orientations, angles, light levels, hairstyles, hats, glasses, facial hair, makeup, ages.

In order to address these challenges, we need to develop advanced algorithms and techinques tailored to the nuances of facial recognition tasks.

Classical Approaches and Their Challenges

Before we dive into the deep learning solution for facial detection and facial recognition, we would like to discuss the three main classical approaches that have been and are currently being used to address this problem. Current approaches include cascade-based methods, DPM-based methods (deformable part models) and neural-network based methods. Each poses difficulties when trying to achieve facial detection and clearly are not the optimized to the best of their abilites.

Classical Approach 1: Cascade Based Methods

The first classical approach uses cascade-based methods which usually either use multiple detectors or combine detectors with other techniques such as integral channel features and soft-cascading to implement facial detection. Soft cascading is a technique that introduces a level of flexibility to regular cascading by allowing a region of interest which is made up of classifiers to be accepted or rejected at each stage based on a weighted combination of the weak classifiers outputs, rather than a strict threshold. In most cases soft-cascading is the preferred method within cascade-based methods due to the computational efficiency gain. The problem with this approach is that it often requires the data to include face orientation annotations. This inherently forces our data to become much larger which ultimately leads to increased complexity in training and testing. Training and testing with this method can become even further complicated when it is required to extend the cascade for multi-view face detection. This increase in complexity cannot be avoided because we must train the model and separate detector cascades for each facial orientation. In conclusion, due to the fact that facial orientation annotations are often a fundamental piece to this approach it drastically limits its practical use in real world applications. These orientation annotations are usually not available when using test data.

Classical Approach 2: DPM Methods

In the area of facial detection, classical approaches such as DPM (deformable part models) have been foundational in detecting facial structures. DPM, an established method, characterizes faces as an assembly of constituent parts, and works to train classifiers capable of discerning the fine relationships among these deformable components. However, while DPM holds promise, its efficiency is often under question by the limitations of individual deformable part models. To fully utilize the capabilities of DPM, practitioners frequently resort to concatenating multiple layers of this approach. As a result, this strategy inherently produces a significant surge in the computational complexity of the overarching model, rendering it unreasonably inefficient. Ultimately, while classical methods like DPM have contributed to our understanding of facial detection, their reliance on intricate part-based modeling and the associated computational overhead underscores the necessity for more streamlined and efficient techniques in contemporary facial detection systems.

Classical Approach 3: Neural Network Methods

The third and final classical approach to facial detection, the neural network approach, leverages convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which represents a significant stride forward in achieving more concrete results. CNNs have demonstrated significant increases in accuracy, particularly regarding scenarios involving varied facial orientations and partial obstructions of facial features. However, despite its advancements, this methodology is not without its limitations. One of the primary shortcomings lies in the generality of the model; while it excels in many cases, it often falls short in delivering highly precise facial detection outcomes. This is mainly due to the fact that these neural networks are not specifically trained or fine-tuned to handle specific facial detection details. Additionally, a notable concern pertains to the tendency of these models to overfit the training data, thereby compromising their ability to generalize well to unseen instances. To address these deficiencies, there is a definite need for the development of more tailored methods that can provide a better analyses of detection scores. By enhancing model training, it may be possible to mitigate the limitations of current neural network-based facial detection systems and create a solution that is both practical and provides accurate results.

Approach Summary

Based on these classical approaches, it is evident that the common problem amongst the three are computational complexity and the failure to bypass facial obstruction or positioning. There needs to be a solution that addresses these concerns, and that solution is to use Deep Learning.

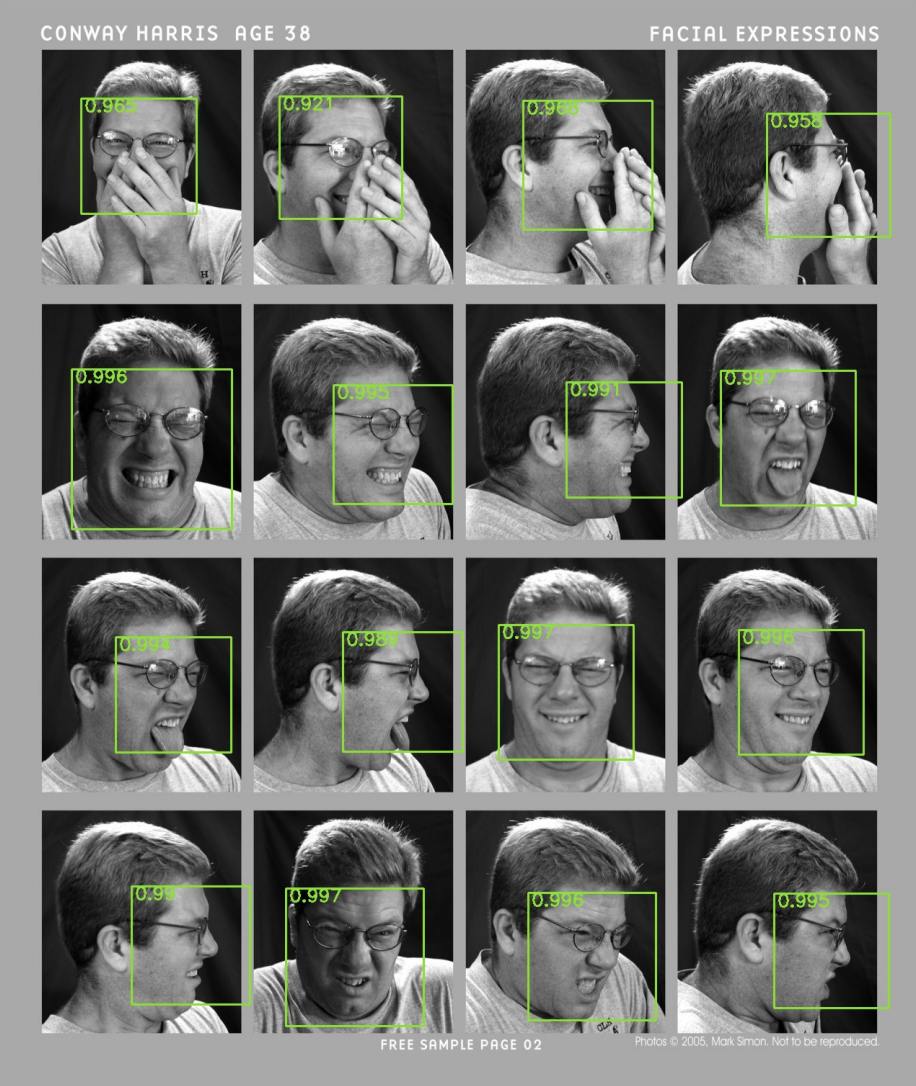

Example of different facial positions and obstructions.

Example of different facial positions and obstructions.

Deep Learning to Address Challenges

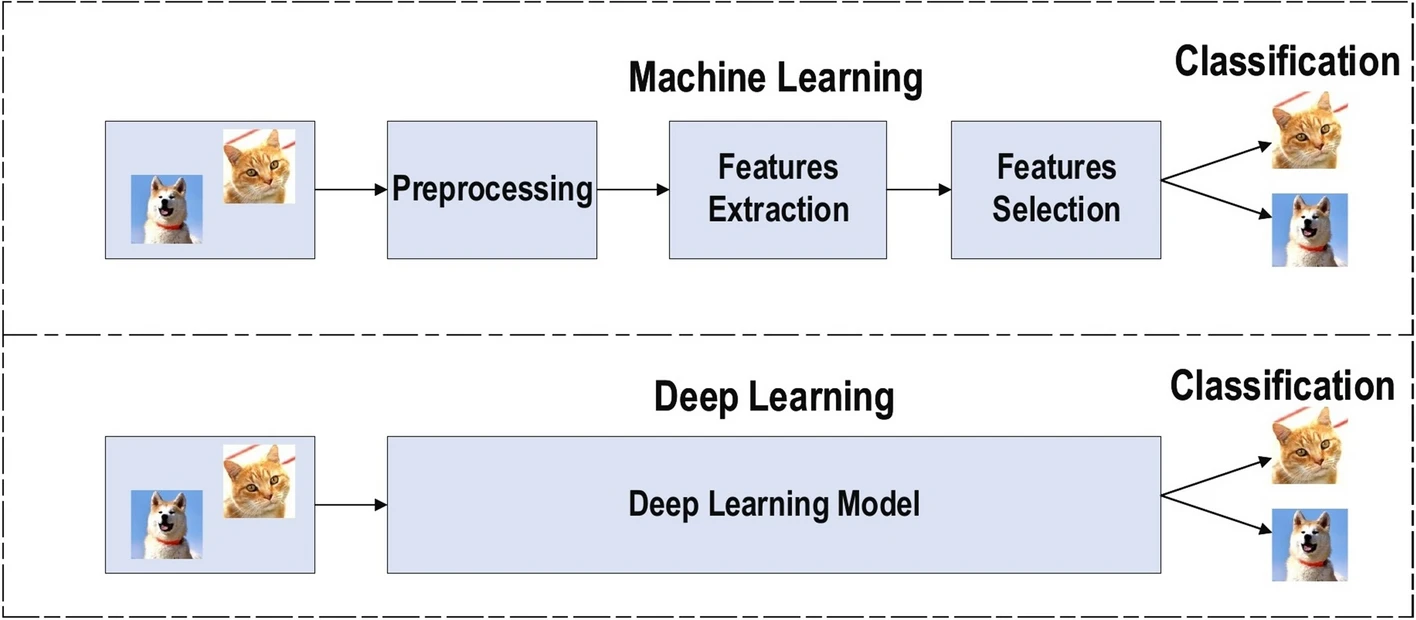

Deep learning and neural networks provide a number of benefits over traditional means of facial detection and recognition addressing the common challenges of the classical approaches. Neural networks learn from a large amount of data and are therefore more robust, efficient, performant, and simple. AI is generally divided into three main branches: artificial intelligence, machine learning, and deep learning. Historically, up to 2010, applied AI was synonymous with machine learning (ML), which involves creating models that learn from historical data to predict future outcomes. A notable limitation of ML is the need for specialized logic to transform raw input—like images—into a set of handpicked features, such as color histograms that numerically represent color distributions, enabling the ML models to learn and make predictions based on these numeric features [3].

Fig 1. Benefits of Deep Learning over Machine Learning in Feature Extraction [2].

Fig 1. Benefits of Deep Learning over Machine Learning in Feature Extraction [2].

The advent of DNNs marks a shift to the third significant phase of practical AI—deep learning. This transition is marked by the use of vast datasets, greater computational power, and a crucial advancement: machines learning autonomously. Deep neural networks (DNNs), comprising interconnected nodes akin to neural pathways in the human brain, excel in identifying and decoding complex patterns. They do this by layering nodes: initial layers decode simple elements, such as an object’s outline, while the more advanced layers discern intricate attributes like texture. Such sophisticated pattern recognition opens the door to a variety of innovative uses across industries.

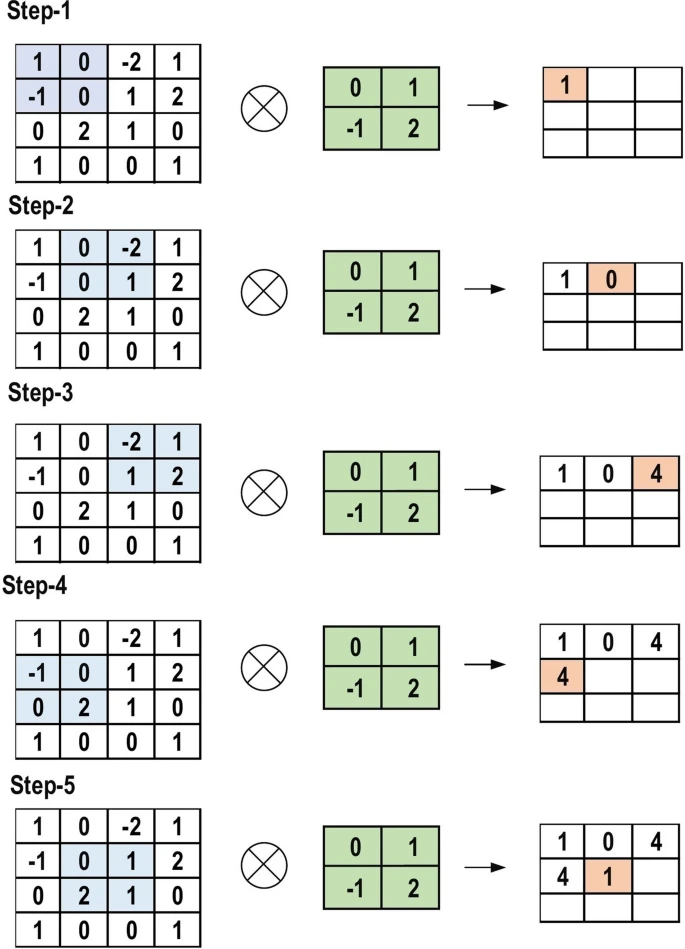

One specific form of DNNs called convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are specially designed to process and classify objects in images. Convolutional neural networks consist of many convolution and pooling layers. At a high level, a convolution layer is responsible for detecting specific features in an image. A convolution layer accomplishes this task by applying a set of learnable filters (called kernels) across an image. Each kernel is designed to activate strongly when it detects a specific feature at a certain spatial position in the image. As the kernel moves across the image, it produces what is called a feature map which represents the presence and intensity of that feature in different regions of the input image. Repeatedly applying convolution layers allows a network to capture highly specific features in a hierarchical fashion making CNNs exceptional at handling visual information.

Fig 2. The primary calculations executed at each step of convolutional layer [2].

Fig 2. The primary calculations executed at each step of convolutional layer [2].

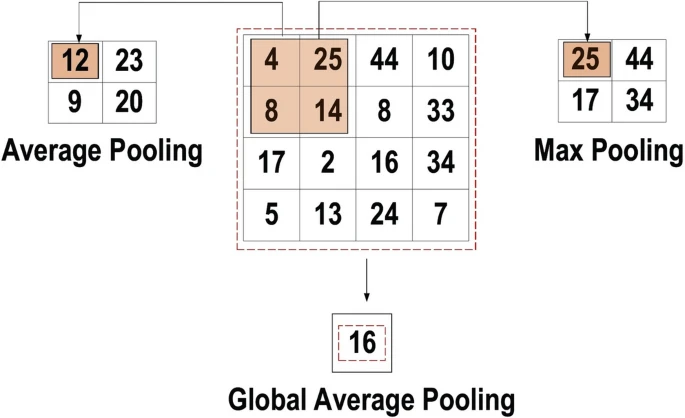

The second key layer in a convolutional neural network is the pooling layer. Pooling layers are interspersed between convolutional layers to reduce the size of the representation thus reducing the number of parameters and computational load the network creates.

Fig 3. Three types of pooling operations [2].

Fig 3. Three types of pooling operations [2].

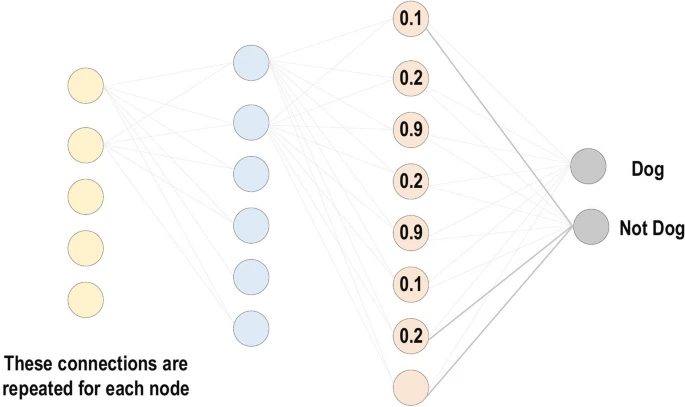

The last and final type of layer that is necessary to understand for a CNN is a “fully connected” (FC) or “linear” layer. After the initial convolution and pooling layers have detected features the FC layers are used to interpret those features and perform classification of the subject of the image. The last layer in the network is commonly a FC layer which has as many nodes as classes in the task (for example 5 neurons for a 5-class classification task). The neurons in the FC layer have full connections to all activations in the previous layer, as their inputs are computed as a weighted sum and a bias offset. Finally a softmax activation function is commonly applied which simply converts the output of the FC layer into normalized probabilities for each class. The class with the highest probability is often taken as the model’s prediction.

Fig 3. Fully connected layer [2].

Fig 3. Fully connected layer [2].

CNNs have a wide set of benefits over traditional methods and have transformed facial detection and recognition via deep learning methodologies like Deep Dense Face Detector (DDFD) and FaceNet. These advanced models offer unparalleled efficiency, robustness, and adaptability, as outlined below.

Multi-view Face Detection: Deep learning models significantly streamline the facial detection process. Unlike traditional approaches that rely heavily on facial landmarks and poses annotations, these models autonomously learn to recognize faces from many orientations. This autonomy in learning enables the detection of faces at various angles and positions, thus simplifying the training process and enhancing the model’s utility across a diverse range of scenarios.

Handling Occlusions and Variations: The hierarchical structure of neural networks enables the detection of partially covered faces and those with significant variations. Early layers in the network might identify basic outlines, while deeper layers discern more complex features such as textures or expressions. This hierarchical learning approach ensures that even when parts of the face are obscured or altered, the network can still identify the presence of a face with incredible accuracy.

Efficiency and Simplification: One considerable advancement brought by deep learning in the realm of facial detection is the conversion of fully connected layers into convolutional ones. This transformation allows models to process images of any dimensionality, effectively reducing the network’s complexity. The result is a more streamlined, efficient process that accelerates the facial detection without compromising accuracy, making deep learning models superior in speed and performance compared to their predecessors. Moreover, the automated learning of customized features makes the creation of neural networks much more simple.

Robustness to Changes: The adaptability of neural networks to new, unseen images underscores their robustness. These networks generalize learnings from training data to accurately recognize faces under conditions not previously encountered, such as different environmental settings or lighting variations. This characteristic is particularly vital for applications requiring high levels of precision across various operational contexts.

Improving with Data Augmentation: Data augmentation techniques play a critical role in enhancing the diversity of training data, which in turn bolsters the model’s robustness. By introducing variations in face size, orientation, and occlusion through methods such as cropping, flipping, and scaling, models are better prepared to generalize from training to real-world applications. This improvement is critical in maintaining high accuracy levels in facial detection across a wide array of situations.

Continuous Improvement: The field of deep learning is characterized by its capacity for ongoing refinement and adaptation. As new data becomes available, models can be retrained or fine-tuned, ensuring they stay at the forefront of facial detection technology. This ability to evolve makes deep learning models particularly valuable, offering solutions that remain effective as the landscape of challenges and requirements shifts.

Solutions

Deep Dense Face Detector (DDFD)

Deep Dense Face Detector, short for “DDFD”, is a method for multi-view face detection that doesn’t rely on pose or landmark annotations.

Existing approaches require training multiple models or additional components like segmentation or bounding-box regression. DDFD, on the other hand, proposes a better, more efficient solution, using a single deep convolutional neural network (CNN). The proposed method achieves comparable or better performance to state-of-the-art methods without the need for complex annotations.

Architecture

Foundationally, DDFD is an AlexNet fine tuned for face detection. AlexNet is an influential and innovative model for image classification leveraging 5 convolution layers for extracting features followed by 3 fully connected layers for classification. DDFD modifies this architecture by converting the final 3 fully connected layers to convolutional ones. This enables the network to process images of any size, liberating it form the constraints of fixed-size input images. Further, because the fully connected layers have been replaced by convolutional once, the network instead outputs a heatmap representing probability of a face at a given location.

Following these convolution layers DDFD employs non-maximal suppression (NMS) to refine the detection process and localize faces. NMS ensures each detected face corresponds to a single precise location by merging overlapping regions. NMS iteratively selects the highest confidence detection and suppresses all nearby detections that significantly overlap.

One strategic choice that sets apart DDFD from other models is its use of a sliding window approach. Most models use a traditional region based approach where regions of interest are predicted before detecting objects within them. Region based approaches are computationally intensive and may miss faces that don’t fit predefined criteria. Instead DDFD leverages a sliding window approach. In this strategy a window slides across the image assessing each window for a face. This drastically reduces complexity and improves detection speed while directly analyzing all areas of an image without the need for any preliminary region proposals.

NMS and the sliding window approach are coupled with a scaling algorithm that enables DDFD to accurately localize faces of different sizes and orientations. DDFD resizes the input image in discrete steps, three times per octave (an octave being a doubling of the image dimension) enabling the detector to scan for faces that could otherwise be missed if they are too small or too large for the default window size. Coupled with NMS and sliding window, the scaling approach contributes significantly to accurate localization of faces. Scaling adjusts the lens to detect faces of all sizes while NMS sharpens the focus, allowing the model to pinpoint the exact location of a face among the expanded search regions. The result is an incredibly robust system which can detect faces in a variety of orientations with high accuracy.

Training Process

DDFD was fine-tuned on the AFLW dataset with 21K images containing 24K face annotations. During training data augmentation was employed through random cropping and flipping, resulting in 200,000 positive and 20M negative examples. The model was trained using 50K iterations with a batch size of 128, including 32 positive and 96 negative examples per batch.

Evaluation Results

DDFD was benchmarked on a variety of datasets including PASCAL Face, AFW, and FDDB datasets showing competitive perofrmance across varied face orientations and occlusions.

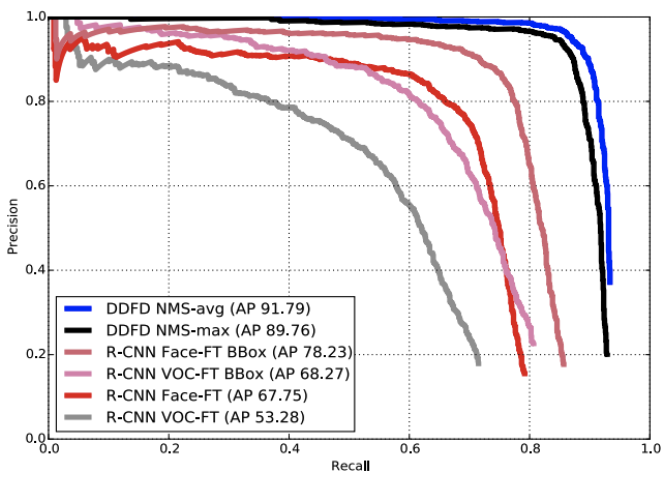

Fig 4. Evaluation of Models on PASCAL Face Dataset [2].

Fig 4. Evaluation of Models on PASCAL Face Dataset [2].

When evaluated on the PASCAL Face Dataset, DDFD demonstrated superior performance compared to R-CNN, especially in handling faces without bounding-box regression or selective search. DDFD achieved this performance by focusing on high recall and precise localization.

Pros and Cons

The Deep Dense Face Detector (DDFD) has emerged as a robust solution in the domain of facial detection, leveraging the strength of CNNs to enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of this process. The benefits of this technology are many, starting with its single-model efficiency. By utilizing a deep convolutional network for both classification and feature extraction, DDFD consolidates the face detection process into a single model. This approach translates to a simplified architecture that negates the need for additional components such as selective search, bounding-box regression, or SVM classifiers, which are traditionally employed in other detection systems. Such a model not only reduces the computational burden but also simplifies the training and implementation phases, resulting in a system that’s both agile and robust.

Another significant advantage of DDFD is its scale invariance. By scaling images up or down in specific increments, DDFD exhibits an ability to detect faces of varying sizes within a single image. This adaptability ensures that the detector does not exhibit any size bias, making it competent in identifying faces regardless of their scale in the image. Coupled with its impressive performance on benchmark datasets such as PASCAL Face, AFW, and FDDB, DDFD has proven its mettle by outperforming some of the existing detection systems, especially in challenging scenarios that do not lend themselves well to bounding-box regression or selective search.

Furthermore, DDFD demonstrates considerable robustness in the detection of faces across a range of orientations and even in partially occluded conditions. This trait is particularly advantageous over many conventional methods, which typically struggle when faced with varying angles and obstructive elements. The ability to detect faces without the necessity for pose or landmark annotations underscores the advanced pattern recognition capabilities of DDFD, positioning it as a highly adaptable and useful tool in the evolving field of facial recognition technology.

However, with these strengths come certain challenges and shortcomings that DDFD must navigate. A notable concern is the model’s dependency on the training data. The performance of DDFD is closely tied to the variety and distribution of positive examples in its training set. A skew towards upright faces could inadvertently lead to a bias, which implies that a balanced and diverse set of training data is crucial for achieving optimal detector performance.

Moreover, the current data augmentation procedures employed by DDFD may not represent the full nature of complexity needed to accurately represent faces in more niche orientations or occlusions. This limitation points to the potential for further improving the performance of DDFD by adopting more sophisticated data augmentation techniques and better sampling strategies. Such enhancements would enable the model to build a more comprehensive understanding of the myriad ways in which faces can present themselves.

DDFD also faces challenges with complex annotations. Although the model does not rely on detailed annotations such as different poses or facial landmarks, it is conceivable that incorporating such data could refine its performance. This area presents a paradoxical duality where the simplicity of the current training methodology, which is one of DDFD’s strengths, also forms a limitation that may be worth exploring in future research efforts.

Lastly, occlusion handling remains an area of improvement for DDFD. While the detector has some capability to manage occlusions, it can struggle with faces that are heavily obscured. This is partly due to the lack of datapoints representing such faces in the training set. Moving forward, it will be crucial to evolve the training data with a wider array of occluded examples to improve the model’s robustness in practical scenarios, where occlusions are a common occurrence.

FaceNet

One interesting system that has made extraordinary headway in facial recognition technology is called Facenet, developed by Google. The paper introduces FaceNet, a system designed to tackle the challenges of efficient face verification and recognition at scale. Unlike traditional approaches, FaceNet directly learns a mapping from face images to a compact Euclidean space where distances represent face similarity. This space enables easy implementation of tasks like face recognition, verification, and clustering using FaceNet embeddings as feature vectors. FaceNet employs a deep convolutional network trained to optimize embeddings directly, rather than using an intermediate bottleneck layer. Training involves triplets of matching/non-matching face patches generated via a novel online triplet mining method. This approach significantly enhances representational efficiency, achieving state-of-the-art face recognition performance with only 128 bytes per face. FaceNet sets new accuracy records, achieving 99.63% on the Labeled Faces in the Wild dataset and 95.12% on YouTube Faces DB, reducing error rates by 30% compared to previous best results.

Moreover, the paper introduces the concept of harmonic embeddings and a harmonic triplet loss, enabling compatibility and direct comparison between different versions of face embeddings produced by various networks. This innovation provides a standardized framework for evaluating and comparing face recognition models. By addressing the challenge of model interoperability, researchers can better understand the strengths and weaknesses of different architectures and approaches. Overall, FaceNet represents a significant advancement in the field of face recognition, offering both superior performance and a standardized methodology for evaluation and comparison.

Architecture

FaceNet leverages a unique architecture which uses a deep CNN trained with a triplet loss function. This approach enables the model to effectively differentiate between distinct facial features across a variety of images, categorizing them into anchor, positive, and negative images. By focusing on the relative differences between categories, the model performs well in creasing precise representations for each face in a 128 dimensional space.

The depth of the convolutional network is also essential in the model’s ability to recognize complex patterns and textures associated with human faces. This depth ensures that later layers can leverage a vast dataset (such as Labeled Faces in the Wild) to learn the most complex features enhancing the model’s ability to recognize faces with high accuracy. [4]

Pros

Efficiency in Training Data: Unlike traditional models that require extensive datasets for training, FaceNet’s effective embedding mechanism significantly reduces the need for large volumes of data. This efficiency not only speeds up the training process but also minimizes storage requirements, making the system more scalable and accessible. [4]

Performance in Recognition: FaceNet’s architecture has led to previously unseen accuracy in facial recognition, outperforming previous systems in both verification and identification metrics. Its ability to process and analyze faces in real-time has revolutionized the field, making it a landmark for security and personal identification. [4]

Versatility: The embeddings generated by FaceNet can be utilized across a spectrum of applications beyond mere recognition. From clustering similar faces in large datasets to enhancing security protocols through verification, the system’s versatility is a significant advantage. [4]

Cons

Resource Intensity: Facenet has high computational cost for training its deep network. Any group seeking to implement the system may face challenges in finding and sourcing the necessary resources, including both hardware and energy consumption, to fully leverage FaceNet’s capabilities. [4]

Potential for Overfitting: The depth and complexity of FaceNet’s architecture, while beneficial for learning detailed features, also pose a risk of overfitting. This could potentially limit the model’s ability to generalize to new, unseen faces, affecting its performance in diverse real-world scenarios.[4]

Final words

When thinking about facial recognition, it is important to keep in mind that alongside its great promise comes a variety of ethical, privacy, and societal concerns, prompting critical discussions on the ethical deployment and regulation of this powerful technology. As facial recognition continues to evolve and be integrated into different aspects of our lives, understanding its capabilities, limitations, and ethical considerations is crucial for shaping its responsible and equitable use in society.

References

[1] Farfade, Sachin Sudhakar; Saberian, Mohammad; Li, Li-Jia. “Multi-view Face Detection Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.” 2015.

[2] Alzubaidi, L.; Zhang, J.; Humaidi, A.J. et al. “Review of deep learning: concepts, CNN architectures, challenges, applications, future directions.” J Big Data. 8, 53 (2021).

[3] Bommasani, Rishi et al. “Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI).” arXiv:2108.07258 [cs.LG]. (2022). https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2108.07258.

[4] [1] Schroff, F.; Kalenichenko, D.; Philbin, J. “FaceNet: A Unified Embedding for Face Recognition and Clustering.” arXiv:1503.03832 [cs.CV] (2015).