Multimodal Vision-Language Models: Applications to LaTeX OCR

LaTeX is widely utilized in scientific and mathematical fields. Our objective was to develop a pipeline capable of transforming hand-written equations into LaTeX code. To achieve this, we devised a two-step model. Initially, we employed an R-CNN model to delineate bounding boxes around equations on a standard ruled piece of paper, utilizing a custom dataset we generated. Subsequently, we passed these selected regions into a TrOCR model pre-trained on Im2LaTeX-100k, a dataset comprising rendered LaTeX images. We further fine-tuned the model on a handwritten mathematical expressions dataset on Kaggle, which is a collection of the CROHME handwritten digit competition datasets over three years [6] [7] [8]. Our model successfully generated the ground LaTeX accurately for 4 out of 8 hand-drawn examples we produced. For the remaining 4 examples, it produced LaTeX similar to the ground truth, albeit with minor errors.

- Introduction

- Related Works

- Methods

- Results

- Discussion & Insights

- Figures

- Codebase

- Citations / References

Introduction

LaTeX is widely known as a markup language primarily used for typesetting and rendering mathematical equations. The typical workflow involves writing LaTeX code, which is then compiled to generate a PDF document. However, there’s a growing interest in reversing this process, particularly when dealing with handwritten text that one wishes to convert into LaTeX.

Handwritten text poses challenges due to inconsistent font. To make this handwritten text machine-interpretable, Optical Character Recognition (OCR) is often employed. However traiditonal OCR often fails because the text can vary in lighting and font, can have occlusions and artifacts, and is often context dependent. Which is why we utilize deep neural networks (DNN) to take handwritten text to LaTeX.

Our approach consists of two main steps. Firstly, we divide the input image into manageable chunks of equations. Subsequently, we utilize another model to convert each chunk into LaTeX format.

LaTeX OCR is particularly useful for individuals who prefer handwriting mathematical equations but wish to scan them into LaTeX without manual transcription. Unfortunately, during our research, we found a scarcity of open-source LaTeX OCR models. Many existing models that perform LaTeX OCR effectively are not open-source, are paywalled, and cannot be executed locally. This poses a problem for scientists, engineers, and students who may be working on proprietary projects or prefer to maintain control over their work. Hence, our objective is to develop a lightweight, and most importantly, open-source model for recognizing mathematical equations.

Related Works

BLIP

One of the first models we looked at was BLIP (Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training), a joint training objective image captioning model [1].

BLIP is an example of a Vision-Language Model, or VLM for short. VLMs span both the image and text domains, and are often used for tasks such as image search and caption generation. In our use-case, we’re looking for a high-resolution captioner to serve as an optical character recognition model. BLIP does just that; think of BLIP as CLIP on steroids, where BLIP models are boosted by being jointly trained on three distinct tasks. BLIP models are also able to bootstrap themselves by being initialized on a small labeled image dataset before improving by generating pseudo-labels for a larger unlabelled image dataset.

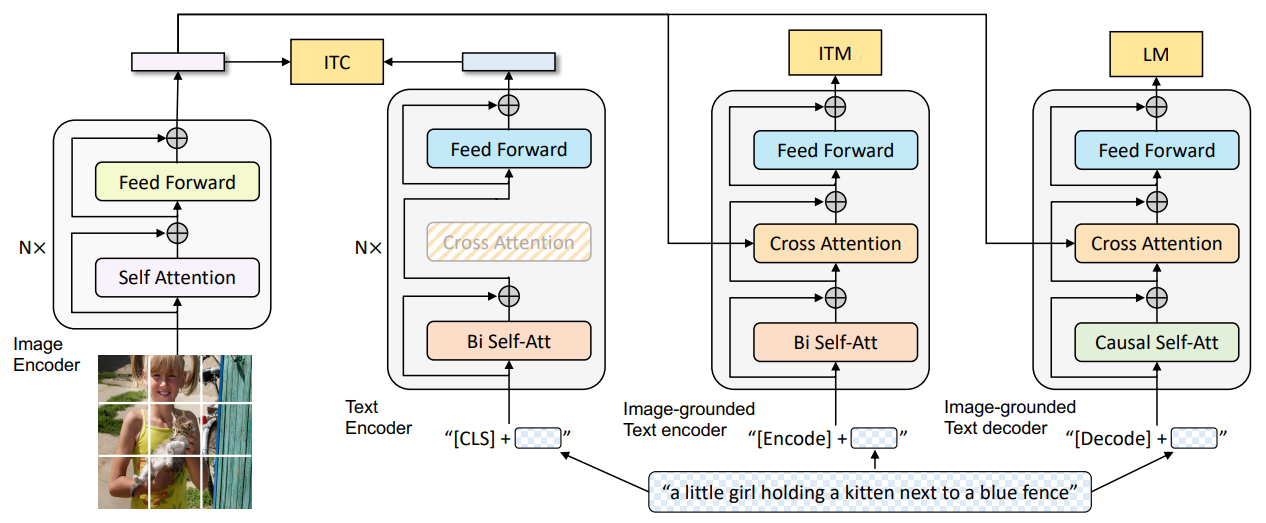

In the diagram above, we can see four distinct models with three training objectives. Let’s break them down, from left to right:

- The model to the very left is the unimodal image encoder, which is an image transformer that embeds the input image to a latent space.

- The second model is the unimodal text encoder, which embeds text captions to the same latent space as the image encoder. A contrastive loss is applied between the two encoders, which is identical to the CLIP training objective.

- The Image-grounded text encoder accepts text as input and cross-attends to the image encoder before generating a sigmoid output. It’s trained on the Image-Text Matching objective, where it’s trained to predict 1 for pairs of images and text captions that correspond to each other and 0 for pairs that don’t.

- The Image-grounded text decoder is a text-only decoder that cross-attends to the image features from the image encoder. It’s trained on an autoregressive Language Model (LM) loss by being tasked to maximize the likelihood of the given text labels for every image.

The main innovation of BLIP over CLIP is that the family of models above are able to complete two tasks simultaneously: generate text labels from images as well as rate the suitability of text labels for a given image. This is how bootstrapping occurs; on the unlabelled dataset, BLIP generates pseudo-text labels for the unlabeled images using its image-grounded text decoder before using the image-grounded text encoder to filter out the low-quality captions.

Our initial thoughts on using this model were that we could use the filtering to help candidate LaTeX texts produced at inference by the decoder. We soon realized that a one-shot approach would perform faster on inference time. Additionally, BLIP had poor training performance (largely because there were no BLIP models that were pre-trained for OCR tasks; when asked to produce a caption for a math formula, our BLIP model would respond with “A math formula.”).

TrOCR

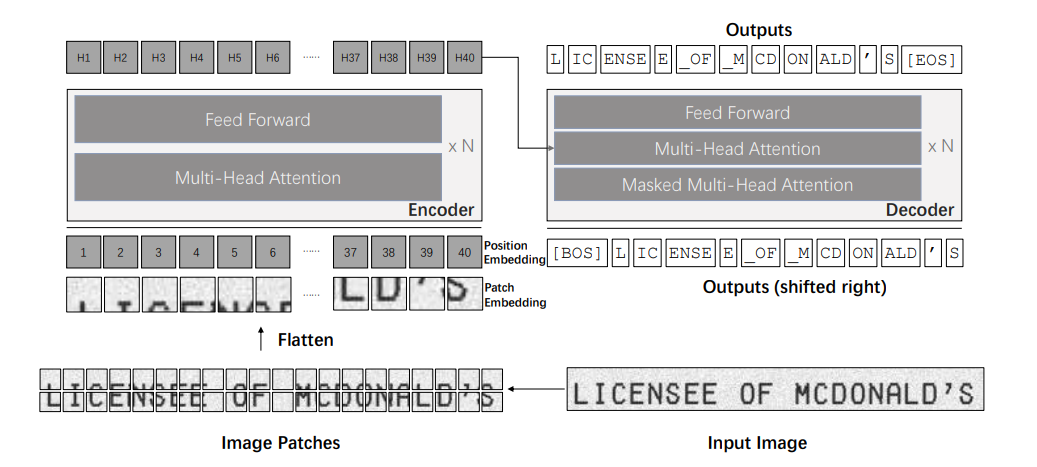

2) TrOCR (Transformer-based Optical Character Recognition with Pre-trained Models), an image text recognition model from Microsoft pre-trained for image handwriting recognition. We finetune it for our task of LaTeX ocr [3]. The architecture is composed of a transformer encoder which encodes an input image and a decoder which tries to produce the text present in the input image.

Transformer Encoder: For the transformed encoder to process the image it must be somehow converted to a sequence of tokens; this is done by breaking the image into 16x16 pixel patches. The transformer encoder is comprised of encoder blocks which each contain two major components. The first is called the self-attention mechanism; this mechanism learns to aggregate image features from different parts of the image together. The second part is called the pointwise feedforward layer; this layer learns how to mix channel information and allows the model to pick out key features for encoding.

Transformer Decoder: The decoder also operates on a sequence of tokens. Unlike the encoder which takes in a fixed number of tokens, the decoder outputs a variable number of tokens. The main difference is that the model autoregressively, token by token, produces the characters of the text as output. Architecturally this means that the self-attention is masked so that the model cannot look ahead when predicting the next token in the sequence. The decoder blocks then has another attention layer that allows the mixing of information from the encoder, allowing the input encoding of the image to inform the text generation. And finally the pointwise feedforward [2].

This is the architecture we choose to finetune on LaTeX and benchmark.

Methods

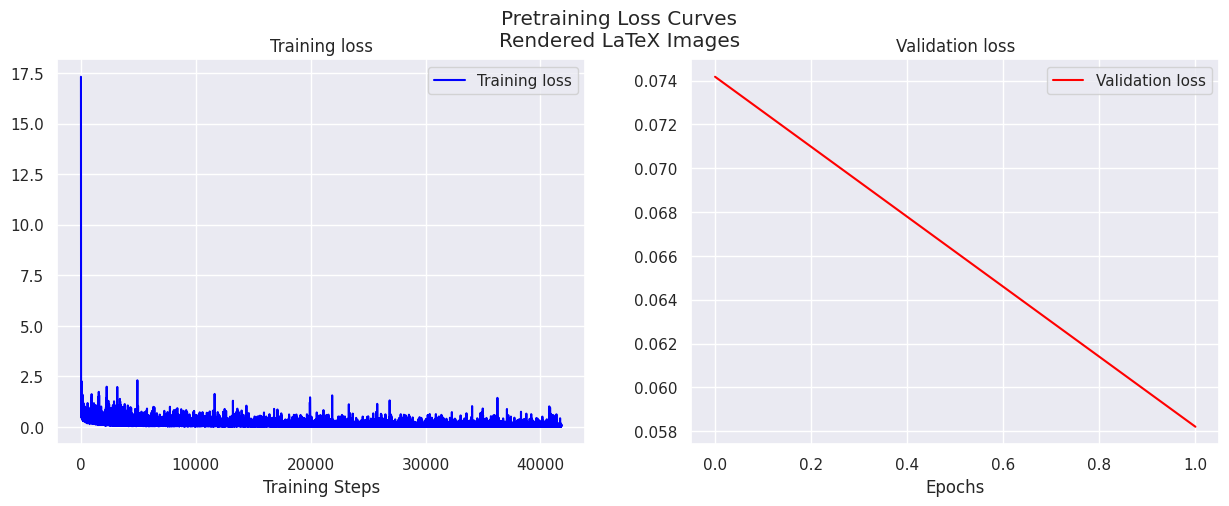

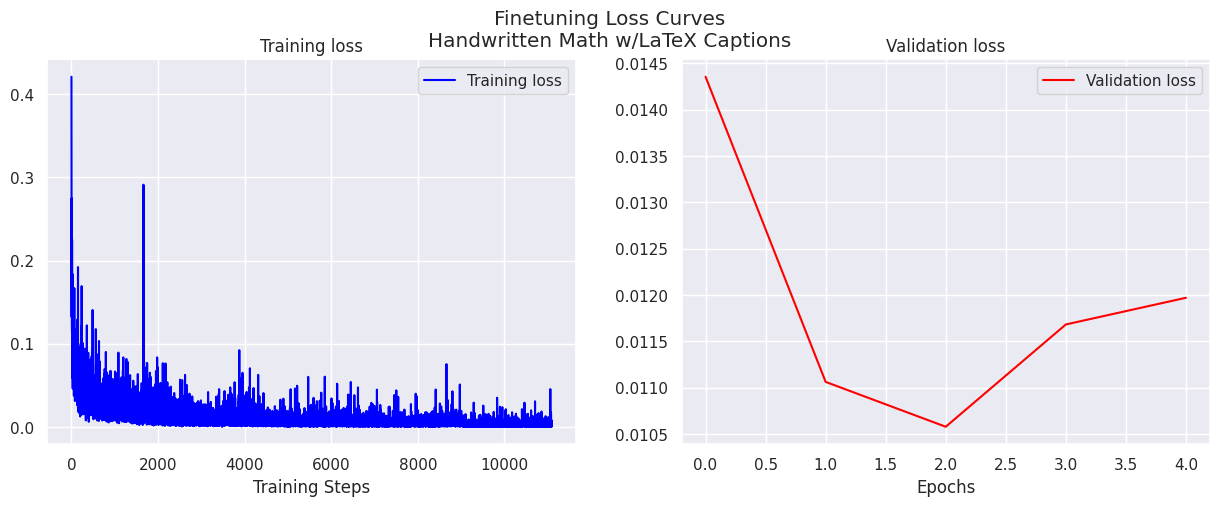

Our datasets consist of the rendered im2Latex dataset as well as the CRHOME subset of Kaggle’s Handwritten Mathematical Expressions. Since there was significantly more rendered equation data (~100k training pairs) compared to handwritten equation data (~10k), we decided to train the models primarily on rendered equations, then fine-tune on the handwritten equations, hoping that the model would generalize well.

Our pipeline consists of two stages: first, a segmentation model, which creates bounding boxes for any equations identified on a scanned page of writing, then, a vision-language model which takes in the coordinates for each bounding box and returns the corresponding LaTex labels for it.

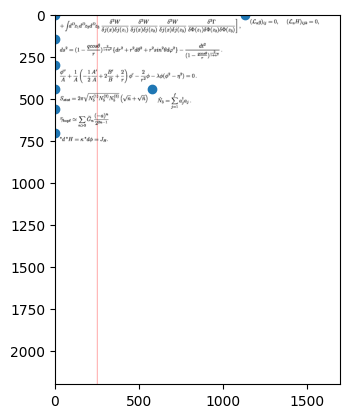

For the segmentation model, we chose to use an RCNN, since it is a relatively simple detection model. Since there was no training data available for our task of detecting equations on a page of mathematical work, we created a script to generate synthetic data by choosing random rendered LaTex to place at various equations at random positions on the page and recording the locations to create bounding boxes. See Figure 8 for one example of a training page fed to the RCNN.

For the vision-language model, we tested the BLIP and TrOCR models. Both models were trained on the im2Latex datasets, and we compared performance using how close the rendered outputs are, since in LaTex sometimes there are slightly different ways to write the equation to get the same results. Correctness in rendered output on handwritten outputs were our ultimate metric, although we used per-token perplexity as a easily evaluatable proxy during training and evaluation.

After training base BLIP and base TrOCR on the im2Latex dataset, we indeed saw that TrOCR had better performance, and thus began additional fine-tuning on TrOCR-Large using the handwritten equation dataset. Credits to Microsoft and HuggingFace for the pre-trained TrOCR implementation we used, which can be found here: https://huggingface.co/microsoft/trocr-large-handwritten.

Results

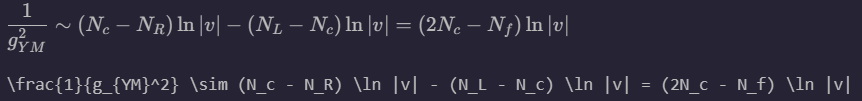

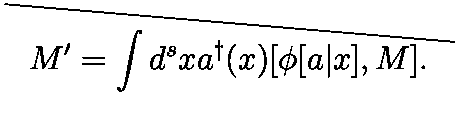

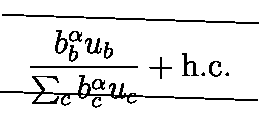

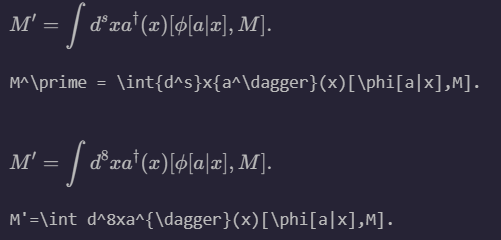

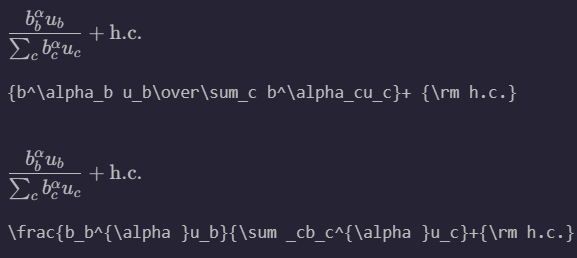

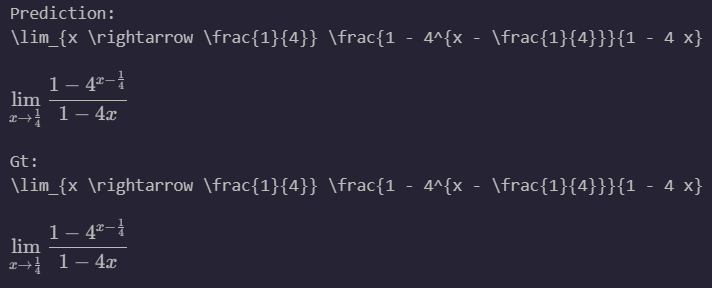

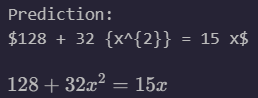

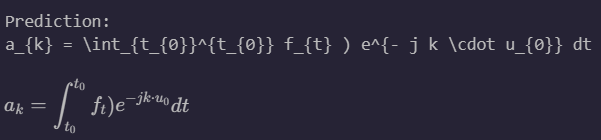

Generally, the model achieved high success on rendered LaTex, able to generate LaTex that compiles successfully and renders identically to the ground truth image. One interesting observation that helped us see that the model did not simply overfit and memorize the LaTex ground truth labels can be seen in Figure 4. For example, the LaTex ground truth label uses \over syntax to represent the fraction, but model learns and correctly outputs a prediction using \frac syntax. Also, where the LaTex ground truth label uses \prime syntax, our model outputs using '. The spacing also varies between the ground truth and our prediction, which makes sense, since LaTex code is spacing invariant.

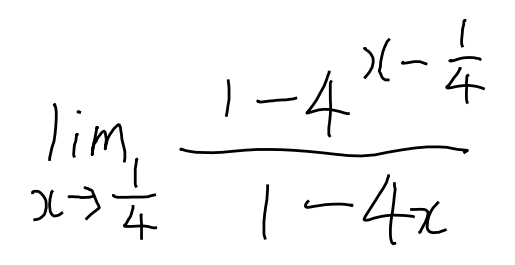

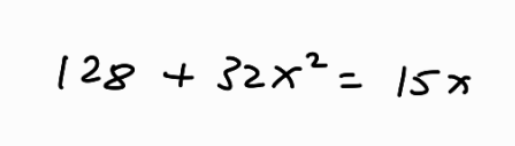

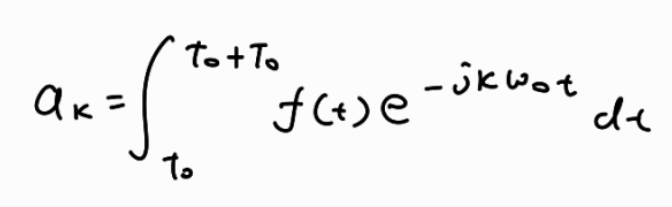

The model also showed high performance in generalizing to handwritten LaTex, both in the validation dataset as well as our own handwritten images. In Figures 5 and 6, we see examples of fully correct (and mostly correct) rendered LaTex outputs. This demonstrates that our model has surprisingly good generalization capabilities. It might be an interesting future project to deploy it for use for real-world equation scanning!

Discussion & Insights

From our preliminary testing, we saw that BLIP’s performance on OCR tasks compared to TrOCR, which makes sense because image captioning is a completely different task compared to optical character recognition, which is extracting text from an image. Thus, a pre-trained BLIP model on captioning image scenes likely would not transfer well to transcribing equations into LaTex code, as that involves more extracting the equation from the image, which is closer to OCR.

We also discovered that pretraining naively on the Im2LaTeX dataset caused a few problems. The model was biased towards more complex equations (it often preferred to produce chi instead of x ). While it was able to achieve almost perfect validation accuracy on the rendered image dataset, it generalized poorly to the handwritten one, achieving only 1/8 accuracy on our out-of-distribution handwritten evaluation sample set. Adding aggressive augmentation to the Im2LaTeX dataset via occlusion, affine transformations, and color jitter — as shown in figure 1 — increased perplexity on the Im2LaTeX validation dataset by a factor of 5 but decreased perplexity on the handwritten validation dataset by a factor of 3. In the end, we were able to achieve 4/8 accuracy on our own handwritten validation set, although it’s worth mentioning that the equations that the model got wrong were admirably close (see figure 6, right).

In the future, we hope to combine our RCNN model with our OCR model in an inference pipeline for near real-time evaluation. Our model currently sits at a hefty 558M parameters, making edge deployment difficult. Future steps to make this project a reality include:

- Model distillation and quantization to improve memory and compute requirements.

- Various tricks to improve model validation performance further (stochastic weight averaging, self-distillation, bootstrapping with pseudo-labels).

- Pipelining and deployment.

We notice that the model has significant issues with details in subscripts or superscripts. Perhaps the image patching mechanism decreases the effective resolutions that our model can distinguish between, which we can test by examining the relationship between patch size and performance. Using a SWIN transformer with a hierarchical feature representation may alleviate this issue.

Figures

Figure 1: Augmented Rendered LaTeX image-label pairs. Note that occlusion augmentation was manually implemented to improve model performance on equations written on line paper.

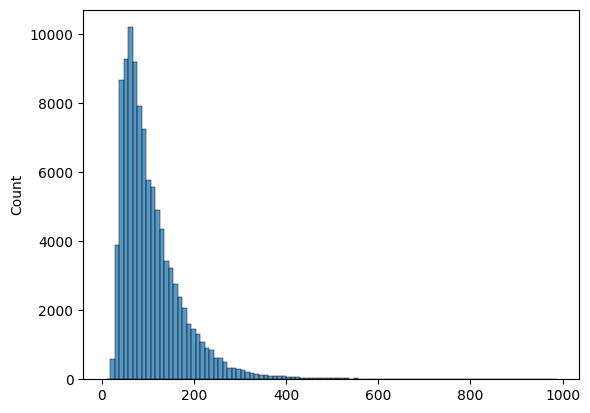

Figure 2: Distribution of rendered LaTeX label lengths (in tokens). Note that the mean label length is significantly longer than even the max label length in the handwritten validation dataset (max length = 182 tokens).

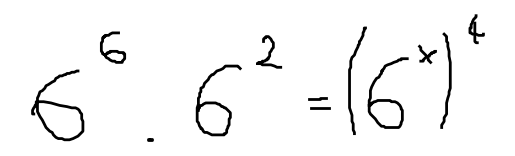

Figure 3: Handwritten LaTeX dataset image-label pair example.

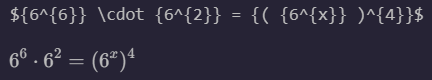

Figure 4: Model performance on the validation subset of rendered LaTeX images. From top to bottom (bottom images): GT, LaTeX of GT, Prediction, Predicted LaTeX.

Figure 5: Model performance on the validation subset of handwritten LaTeX images.

Figure 6: Model performance on out-of-distribution handwritten images (handwritten by us on a tablet).

Figure 7. Pretraining loss curves, with the pretraining dataset being the Im2LaTeX-100k.

Figure 7: Finetuning loss curves, with the fine-tuning dataset being the CROHME subset of the Kaggle Handwritten Mathematical Expressions Dataset. Note the decreased per-token perplexity compared to the pretraining loss curves.

Figure 8: Training sample for the RCNN model. The blue dots represent the extrema of each bounding box.

Codebase

Our Github repository can be found here: https://github.com/leonlenk/LaTeX_OCR/tree/main.

Weights for the latest fine-tuned TrOCR model can be found here: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1tQHq0stWY6BXwvoFaWAGnVG4EYVltxPs?usp=sharing

Citations / References

[1] Junnan Li, Dongxu Li, Caiming Xiong, and Steven C. H. Hoi. BLIP: bootstrapping language-image pre-training for unified vision-language understanding and generation. CoRR, abs/2201.12086, 2022.

[2] Minghao Li, Tengchao Lv, Lei Cui, Yijuan Lu, Dinei A. F. Florˆencio, Cha Zhang, Zhoujun Li, and Furu Wei. Trocr: Transformer-based optical character recognition with pre-trained models. CoRR, abs/2109.10282, 2021

[3] Alec Radford, Jong Wook Kim, Chris Hallacy, Aditya Ramesh, Gabriel Goh, Sandhini Agarwal, Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Pamela Mishkin, Jack Clark, Gretchen Krueger, and Ilya Sutskever. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. CoRR, abs/2103.00020, 2021.

[4] Shaoqing Ren, Kaiming He, Ross B. Girshick, and Jian Sun. Faster R-CNN: towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. CoRR, abs/1506.01497, 2015.

[5] Alexey Dosovitskiy, Lucas Beyer, Alexander Kolesnikov, Dirk Weissenborn, Xiaohua Zhai, Thomas Unterthiner, Mostafa Dehghani, Matthias Minderer, Georg Heigold, Sylvain Gelly, Jakob Uszkoreit, and Neil Houlsby. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. CoRR, abs/2010.11929, 2020.

[6] Mouchère H., Viard-Gaudin C., Garain U., Kim D. H., Kim J. H., “CROHME2011: Competition on Recognition of Online Handwritten Mathematical Expressions”, Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, ICDAR 2011, China (2011) (PDF)

[7] Mouchère H., Viard-Gaudin C., Garain U., Kim D. H., Kim J. H., “ICFHR 2012 - Competition on Recognition of Online Mathematical Expressions (CROHME2012)”, Proceedings of the International Conference on Frontiers in Handwriting Recognition, ICFHR 2012, Italy (2012) (PDF)

[8] Mouchère H., Viard-Gaudin C., Zanibbi R., Garain U., Kim D. H., Kim J. H., “ICDAR 2013 CROHME: Third International Competition on Recognition of Online Handwritten Mathematical Expressions”, Proceeding of the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition - International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition, USA (2013)

[9] Yuntian Deng, Anssi Kanervisto, and Alexander M. Rush. What you get is what you see: A visual markup decompiler. CoRR, abs/1609.04938, 2016