Human Mesh Recovery

WHAM: Reconstructing World-grounded Humans with Accurate 3D Motion. Human Mesh Recovery (HMR) is a computer vision task that involves reconstructing a detailed 3D mesh model of the human body using 2D images or videos. In the 2D realm, we have seen solutions to extract 2D key points. Now, HMR aims to go a step further by capturing the shape and pose of the human body.

Introduction

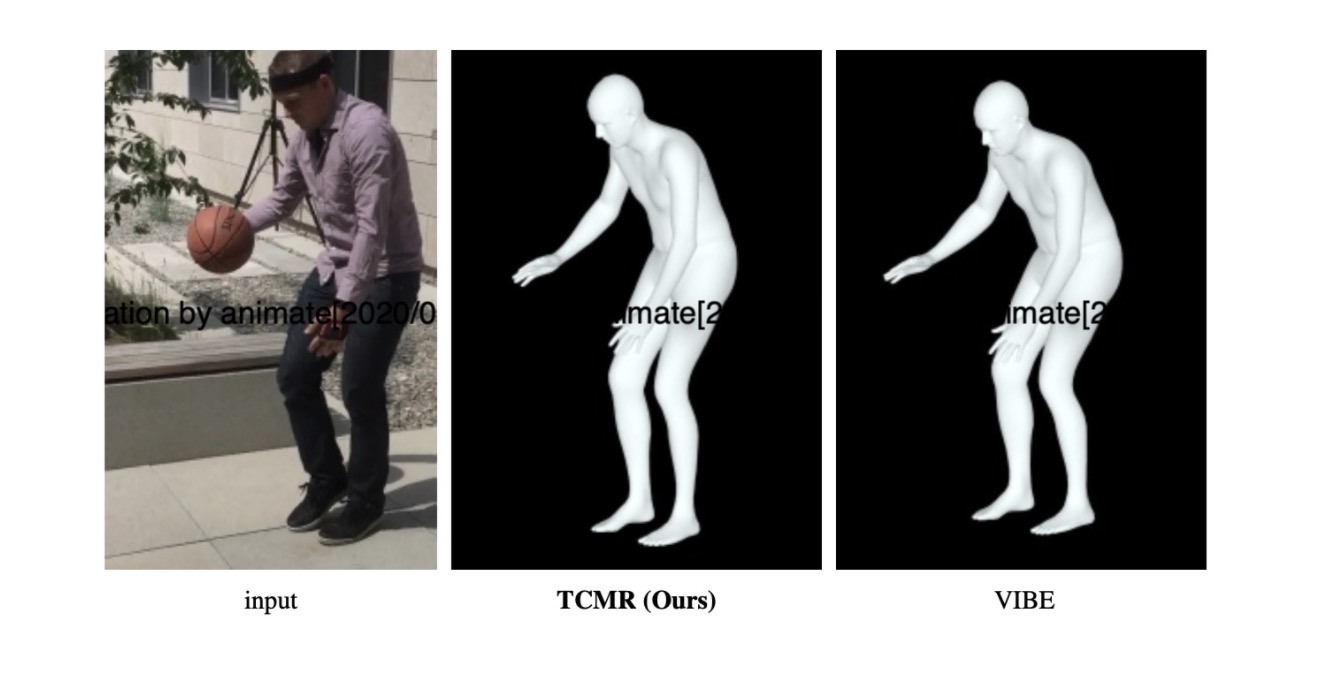

Human Mesh Recovery (HMR) is a computer vision task that involves reconstructing a detailed 3D mesh model of the human body using 2D images or videos. In the 2D realm, we have seen solutions to extract 2D key points. Now, HMR aims to go a step further by capturing the shape and pose of the human body. Solutions such as TCMR and SLAHMR introduced novel methods to capture these meshes and employ them in videos. However, they are limited by their slow inference time and inflexible requirements for input videos. We will conclude by discussing the WHAM architecture which improves on the prior models’ shortcomings through a novel foot-ground contact predictor.

Approaches

TCMR

Overview

Since previous methods are image-based, there is a strong dependency on static features. With video, there is a new problem of linking a single motion across multiple frames. TCMR (temporally consistent mesh recovery) focuses on temporal information from surrounding frames instead of just the current static feature from the current frame. It uses PoseForecast, a temporal encoder that takes in two frames and generates an intermediate frame. In doing so, the 3D pose and shape accuracy are also greatly improved.

Methodology and Architectural Details

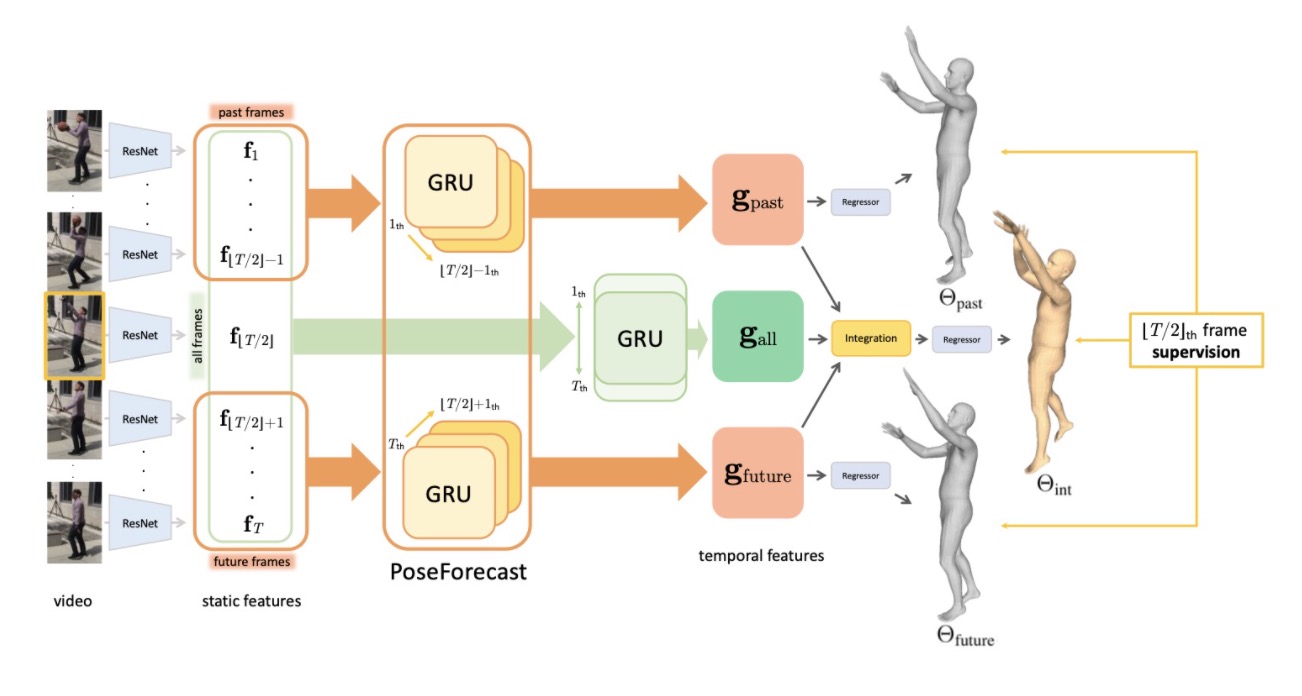

The pipeline is as follows: first, frames of the video are fed through ResNet to extract static features. Features from the past and future frames are then inputted into PoseForecast, a temporal encoder that figures out temporal features. The current frame is also fed through its own temporal encoder and combined with the other frames, finally creating the frames.

To create features, all frames start off by going into a pretrained ResNet network. Global average pooling is then done to the outputs to get the final features. The temporal encoding for the current frame is done via a bi-directional GRU, with one direction extracting the new features going forwards and the other extracting features going backwards. Each GRU’s states are recurrently updated by aggregating static features from the following frames, starting at the furthest frames and finally ending at the current frame.

Given an input size of \(T\) frames (window size), the current frame would be \(T/2\), and so one direction will extract features from \(1, \ldots, T/2\) while the other direction will extract features from \(T, \ldots, T/2\). \(T\) can be increased to capture a larger window of temporal features, or decreased (\(T=1\) behaves as if there were no temporal features at all). Thus, the end result is at the current frame, and that becomes the current temporal feature in the network. In order to reduce the dependency on the current frame’s static features, there are no residual connections between the static features and temporal features.

In addition, PoseForecast adds temporal features from the past and future frames. Past frames are frames from \(1, \ldots, T/2-1\) and future frames are frames from \(T/2+1, \ldots, T\). Going forwards, frame 1’s hidden state is initialized as a zero tensor, and then as the frame increases, the hidden state is recurrently updated. The final hidden state represents the temporal features from the past frames. Going backwards, the process is similar, with a zero tensor for frame \(T\) and the hidden state being recurrently updated.

At this point, we have temporal features from all frames \(g_\text{all}\), past frames \(g_\text{past}\), and future frames \(g_\text{future}\). Each of these are passed through layers (ReLU, FC, resize, FC, and softmax) to create attention values for feature integration. These attention values \alpha represent how much weight should be put into past and future features. By multiplying the three attentions with the corresponding features and adding everything together, the final temporal features is obtained. Loss is calculated via the 2D and 3D joint coordinates.

\[g'_\text{int} = \alpha_\text{all} g'_\text{int} + \alpha_\text{past} g'_\text{past} + \alpha_\text{future} g'_\text{future}\]For TCMR, a value of \(T=16\) was used for videos of 30 frames per second. Weights were updated using the Adam optimizer with a mini-batch size of 32. Frames were also cropped and occluded with various objects for data augmentation. This augmentation was effective in reducing pose and acceleration errors. When training, the learning rate was decreased by a factor of 10 when 3D pose accuracy did not improve after every 5 epochs.

Summary

TCMR solves the issue of temporal consistency by employing two key elements. First, the residual connection between the static and temporal features is removed to reduce dependency on static features. Second, the introduction of PoseForecast predicts the current temporal feature based on past and future frames.

SLAHMR

Overview

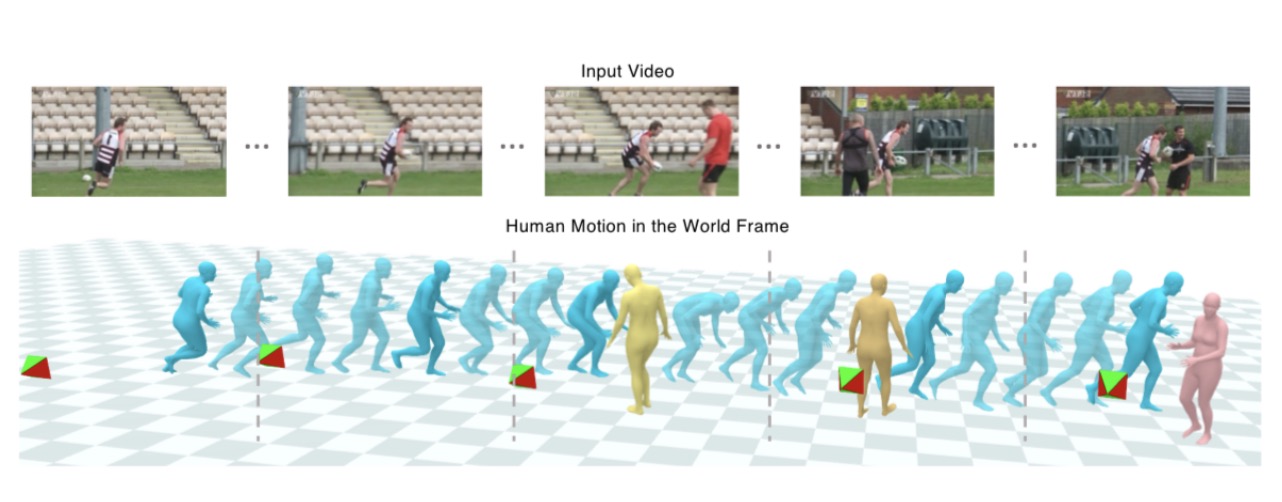

SLAHMR (Simultaneous Localization and Human Mesh Recovery) was another novel method released in 2023 that infers 4D human motion from videos - a 3D mesh in a world coordinate space with motion relative to time. SLAHMR was able to separate camera motion from human motion and thus project the 3D mesh into world coordinates. Previously existing methods would often either infer motion from the camera motion, modeling the mesh from the point of view of the camera, or inferring the scene via the backgrounds. Furthermore, SLAHMR is able to also derive the motion of multiple people in one shot.

Methodology

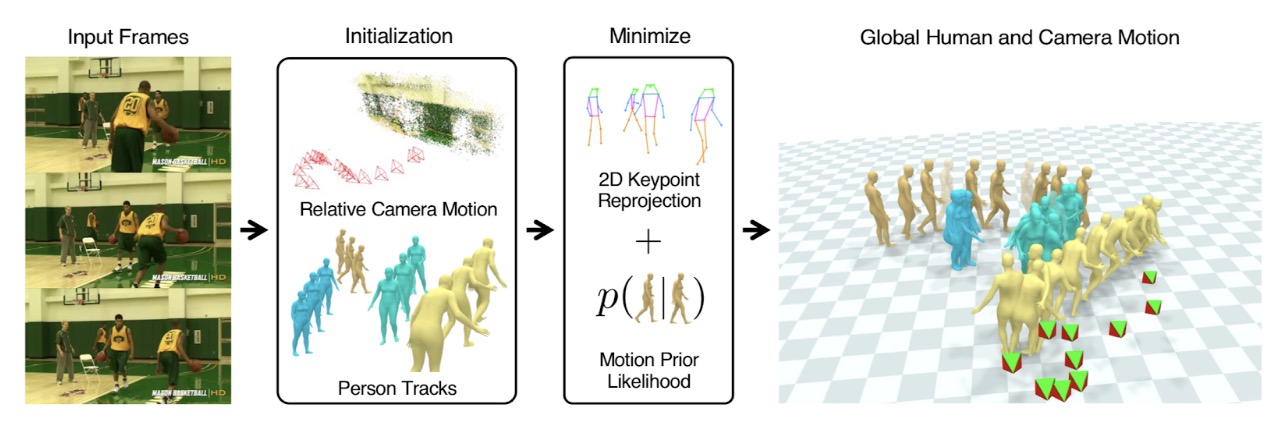

SLAHMR takes in an RGB video as input and uses a SLAM-based architecture to model the camera motion from the motion of pixels in the video. This camera motion is then used to optimize a global trajectory of the motion. They denoted two key insights in their model that enabled this optimization - using “scene parallax” to reasonably estimate scene reconstruction, as well as learned priors for human motion using EgoBody, “a new dataset of videos” defining human motion. Like WHAM, which we will discuss later, as well as other 3D human mesh reconstruction models, SLAHMR similarly takes inspiration from the existing SMPL model in their architecture. They also utilize aspects of the PHALP architecture, which is used to predict 3D poses of the humans within a scene. The pipeline is as follows, where DROID-SLAM and PHALP are used to estimate the camera motion and human poses, upon which they use prior likelihoods and reprojections to generate the SMPL-based meshes:

Summary

SLAHMR proved significant improvements upon state of the art models using the EgoBody dataset, namely PHALP, VIBE, and GLAMR, with significantly lower error and greater efficacy in terms of its trajectory generation and pose estimation. Though SLAHMR still demonstrated room for improvement in multi-pose 3D mesh generation, it proved an effective model for both generating multiple poses as well as generating trajectories of 3D meshes in a world coordinate space through its novel approach in decoupling the camera motion from the human motion of a video.

WHAM

Introduction

World-Grounded Humans with Accurate Motion (WHAM) is a recent approach that estimates 3D human motion and trajectory more accurately and quickly than current state-of-the-art models. Unlike other computer vision solutions, WHAM projects the camera to global coordinates, removing camera view dependence. WHAM also uses foot-ground contact probability to more accurately model the subject’s movements off the ground (ex: climbing up a set of stairs).

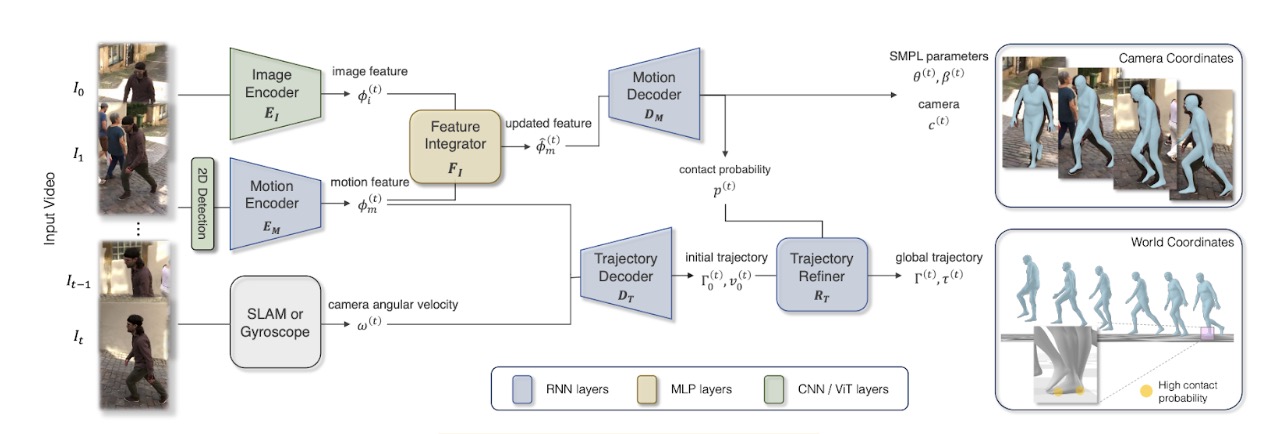

As shown in the figure above, WHAM performs 2 main tasks: estimating motion and trajectory.

Estimating Motion

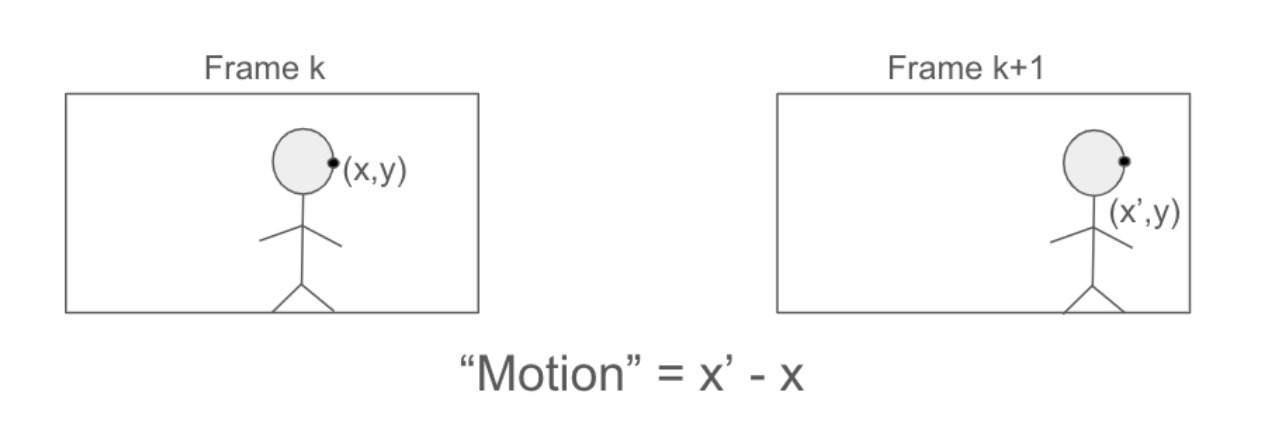

WHAM first detects 2D key points in the video frames using ViTPose. These points will be useful for motion feature extraction later on in the pipeline. Because of object rotation and movement between frames, the key points are then normalized to a bounding box around the person. Now motion context can be derived from them.

The figure above gives an example of motion feature extraction from key point comparison between frames. The movement of the key point on the person’s face captures their rightward movement. The difference in the x coordinates between the key point instances quantifies this movement. The motion encoder in Figure 1 is responsible for encoding this movement into a motion feature 𝜙m(t), where m represents the feature index and t represents the frame number.

However, displacement of 2D key points isn’t enough to understand the subject’s 3D pose. The solution is to use an image encoder that extracts visual information from the scene. The visual cues \(\phi_i^{(t)}\) enrich the motion information to effectively generate the subject’s 3D pose. The feature integrator FI combines the motion context \(\phi_m^{(t)}\) and visual context \(\phi_i^{(t)}\) into enriched motion features using a simple residual connection:

\[\hat{\phi}_m^{(t)} = \phi_m^{(t)} + F_I \left( \text{concat} \left(\phi_m^{(t)}, \phi_i^{(t)} \right)\right)\]Finally, the motion decoder recovers Skinned Multi-Person Linear parameters which capture the subject’s shape and pose. THe decoder also provides the weak-perspective camera translation \(c\) and foot-ground contact probability \(p\). This probability is used to refine the trajectory generated by the model’s trajectory decoder.

Estimating Trajectory

The model architecture in Figure 1 outlines a 2-stage pipeline to estimate trajectory: trajectory decoding and refinement. The Trajectory Decoder \(D_T\) predicts the global root orientation \(\Gamma_0^{(t)}\) and root velocity \(v_0^{(t)}\) from the motion feature \(\phi_m^{(t)}\). However, since the motion features are extracted from the frame which resides in camera space, it is hard to decouple the human and camera information from these features. Thus, the camera’s angular velocity is appended to the motion feature to create a camera-independent motion context. The final global orientation and velocity can now be accurately computed:

\[\left(\Gamma_0^{(t)}, v_0^{(t)} \right) = D_T \left(\phi_m^{(0)}, \omega^{(0)}, \ldots, \phi_m^{(t)}, \omega^{(t)} \right)\]While most human motion and trajectory models stop here, WHAM uses a trajectory refiner that allows it to avoid foot sliding and generalize motion to beyond flat ground planes. For foot sliding, if the foot-ground probability \(p\) calculated by the motion decoder is greater than some threshold, an additional velocity \(v_f^{(t)}\) is introduced. This velocity is the average velocity of the toes and heels in the world coordinate. The final root velocity is then calculated as follows:

\[\tilde{v}^{(t)} = v_0^{(t)} - \left(\Gamma_0^{(t)}\right)^{-1} \bar{v}_f^{(t)}\]Finally, the global translation is computed using a roll-out operation:

\[\begin{align*} \left(\Gamma^{(t)}, v^{(t)} \right) &= R_T \left(\phi_m^{(0)}, \Gamma_0^{(0)}, \tilde{v}^{(0)}, \ldots, \phi_m^{(t)}, \Gamma_0^{(t)}, \tilde{v}^{(t)} \right) \\ \tau^{(t)} &= \sum_{i=0}^{t-1} \Gamma^{(i)} v^{(i)} \end{align*}\]Training

WHAM is trained in two distinct steps. First, the model is trained with synthetic data from the AMASS dataset. This helps the model learn to extract motion context from keypoint sequences while also teaching the decoders to map this motion context to the 3D realm. Second, the model gets fine tuned from real world video datasets which contain less ground truth data. This helps train the feature integration which combines motion and image context together.

Comparisons

Quantitative Comparisons

Test Data

The datasets are tested using three different benchmarks: 3DPW, RICH, and EMDB datasets. Global trajectory is only measured on the EMDB dataset which contains ground truth global motion with camera coordinates.

Evaluation Metrics

These models are compared using four evaluation metrics to measure per-frame accuracy and inter-frame smoothness: Mean Per Join Position Error (MPJPE), Procrusted-aligned MPJPE (PA-MPJPE), Per Vertex Error (PVE), and Acceleration error (Accel, \(\text{m/s}^2\)).

MPJPE measures the average distance between the predicted and ground truth human joint positions. PA-MPJPE first aligns the predicted pose to the ground truth pose using a Procrustes transformation which accounts for translation, rotation, and scaling differences between both poses before conducting the same MPJPE evaluation. PVE measures the discrepancy between the estimated 3D model vertices and the ground truth vertices. Finally, acceleration error measures the smoothness of the reconstructed motion.

Global trajectory estimation is evaluated by breaking the input into 100 frame chunks and aligning the output with the ground truth using either the first two frames or the entire 100-frame dataset, W-MPJPE \(_{100}\) and WA-MPJPE \(_{100}\), respectively. Error for the entire trajectory is also calculated to account for drift during long videos. This is achieved by evaluating the Root Orientation Error (ROE), Root Translation Error (RTE), and Ego-centric Root Velocity Error (ERVE).

ROE measures the angular error between the orientation of the root joint in the estimated mesh and the ground truth. RTE measures the translational error for the root joint across individual frames. Finally, the ERVE metric measures the error in predicting the velocity of the root joint with the perspective centered around the individual.

Comparison

For the following metrics, we will consider the WHAM-B (ViT) model. This model used the BEDLAM dataset with video SMPL parameters used as ground truth. Additionally, the image features are extracted via a ViT model. All metrics are given in mm except for Accel which is measures as \(\text{m/s}^2\).

Errors for TRACE, SLAHMR, WHAM-B on the 3DPW dataset.

| PA-MPJPE | MPJPE | PVE | Accel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRACE | 50.9 | 79.1 | 95.4 | 28.6 |

| SLAHMR | 55.9 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| WHAM-B | 37.2 | 59.4 | 71.0 | 6.9 |

Errors for TRACE, SLAHMR, WHAM-B on the RICH dataset.

| PA-MPJPE | MPJPE | PVE | Accel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRACE | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| SLAHMR | 52.5 | N/A | N/A | 9.4 |

| WHAM-B | 44.7 | 82.6 | 93.2 | 5.6 |

Errors for TRACE, SLAHMR, WHAM-B on the EMDB dataset.

| PA-MPJPE | MPJPE | PVE | Accel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRACE | 70.9 | 109.9 | 127.4 | 25.5 |

| SLAHMR | 69.5 | 93.5 | 110.7 | 7.1 |

| WHAM-B | 48.8 | 80.7 | 93.7 | 5.9 |

Despite some missing data, one should observe WHAM’s stronger performance across the multiple datasets.

Below are the global motion estimation errors between the different models. Here, WHAM uses a gyroscope on the video camera to calculate the camera angular velocity. RTE is measured in \(m\), ROE in degrees, and ERVE in \(mm/\text{frame}\).

| PA-MPJPE | W-MPJPE100 | WA-MPJPE100 | RTE | ROE | ERVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TRACE | 58.0 | 2244.9 | 544.1 | 18.9 | 72.7 | 370.7 |

| SLAHMR | 61.5 | 807.4 | 336.9 | 13.8 | 67.9 | 19.7 |

| WHAM | 41.9 | 436.4 | 165.9 | 7.1 | 26.3 | 14.8 |

Runtime

WHAM can quickly generate human meshes for videos compared to other models. For instance, the authors tested WHAM and SLAHMR with video footage containing 1000 frames. They observed that WHAM would take 4.3 seconds to extract image features and 0.7 seconds to process motion and trajectory, bringing the total runtime to 5.0 seconds. This data excludes basic feature identification which have existing real-time solutions. It also excludes running SLAM since this could be replaced with gyroscope data. For the same dataset, SLAHMR took 260 minutes to generate its human mesh. Due to its efficiency by running over 3000x faster than similar models, WHAM can be used as a practical tool while other models would be lagging in throughput.

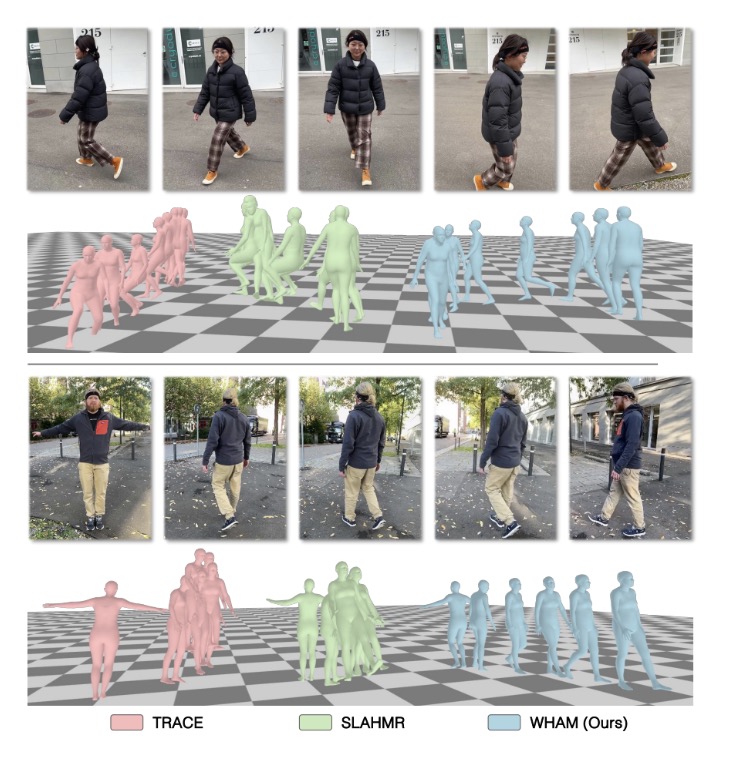

Qualitative Comparisons

This example highlights WHAM’s ability to manage the global position of the user using its insight on foot-ground contact and incorporating that into its global trajectory calculation. On the other hand, both TRACE and SLAHMR do a poor job at maintaining an accurate interpretation of the person’s location.

Our Own Videos

In addition to the paper’s comparions and demo videos, we also tried running our own video on SLAHMR and WHAM. The following is the output from SLAHMR:

The whole thing took approximately 4 hours to run on Google Colab T4. Around 2 hours were used to download all the required files and another 2 hours were used to generate the video. Note that the original video is 19 seconds long but the SLAHMR output is only 6 seconds long; part of the video was not processed. There were also some errors in the notebook that had to be fixed before the output could be generated.

The following is the output from WHAM:

WHAM was much, much quicker, only taking 10 minutes to generate the video. Additionally, all 19 seconds of the video were generated. Due to the simplicity of movements, there was not much difference between the two models. Low contrast in the video between the walls and person made some limbs inaccurate, but they stayed on the human subject well for the most part. One key part where WHAM performed better was the foot liftoff, where the heel would noticeably leave the ground when taking steps around the room. Compared to SLAHMR, in which the feet would glide slightly with the walking, WHAM looks noticeably better anchored and realistic looking.

References

- WHAM: Reconstructing World-grounded Humans with Accurate 3D Motion; arXiv:2312.07531 [cs.CV]

- Beyond Static Features for Temporally Consistent 3D Human Pose and Shape from a Video; arXiv:2011.08627 [cs.CV]

- Decoupling Human and Camera Motion from Videos in the Wild; arXiv:2302.12827 [cs.CV]

- A survey on real-time 3D scene reconstruction with SLAM methods in embedded systems; arXiv:2309.05349 [cs.RO]