Exploring Various State-of-the-Art Techniques in Diffusion Models

In this study, we discuss and analyze various state-of-the-art works for diffusion models. From our research, we can see that diffusion models are continously being improved frequently. In addition, we found that previous works help inspire new works, pushing the bounds of diffusion models even further. With this blog article, we hope to inspire some interest and enthusiasm in the blooming field of diffusion models.

- 0. Introduction

- 1. Background: Understanding the Foundations

- 2. Stable Diffusion (Dec 2021) [8]:

- 3. Stable Diffusion 3 (Mar 2024) [9]:

- 4. REPA: Representation Alignment (Oct 2024) [10]

- 5. REPA-E: End-to-End Representation Alignment (Apr 2025) [12]

- 6. Comparing Methods

- 7. Conclusion

- 8. References

0. Introduction

As our world becomes intertwined with AI, we are witnessing more and more technological breakthroughs at a fast pace. One field that has exploded in popularity is generative AI, where diffusion models are used to generate realistic images, voices, videos, and other types of digital data. While current diffusion models are generating very impressive results, they still suffer from high computational resources, unstable training, hallucinations, and poor visual representation. For example, recently Google announced Veo-3, a new video AI generator model that creates very controllable photo-realistic videos with audio. Even though the new model pushes the boundaries of video generation, it still suffers from common issues such as maintaining consistency and generating complex motion [1]. Thus, it’s imperative for researchers to continue to explore and discover new methods of improving diffusion models so that we can reach new heights in the field of generative AI.

The focus of this study blog is to delve into and analyze the various state-of-the-art techniques used in diffusion models today. We want to highlight some interesting recent works and give a preview on what is coming out.

1. Background: Understanding the Foundations

1.1 What Are Diffusion Models?

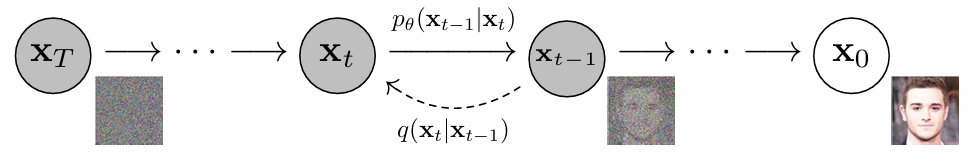

Figure from DDPM paper [2].

Diffusion models are a type of generative AI model that generate images by gradually reversing a noising process from a noisy image. During pre-training, real-world images are passed to the model. In the forward process, Gaussian noise is incrementally added to the images until they become solely noise. Then, in the backward process, the model attempts to predict the noise at each step to denoise the input, ultimately reconstructing the original image. During inference, the diffusion models start with a completely random noisy image and are tasked with predicting the noise to denoise the image. Some diffusion models also take in text input to help guide and control the generations as well. Ultimately, there are many variations of diffusion models, but their main goal is to generate realistic images by predicting noise in noisy images.

While diffusion models are highly effective and can generate incredible results, they are computationally demanding due to the large number of iterative steps, size of model, and unstable training. However, researchers are constantly discovering new ways of improving diffusion models in both performance and efficiency.

1.2 UNet: The Original Workhorse

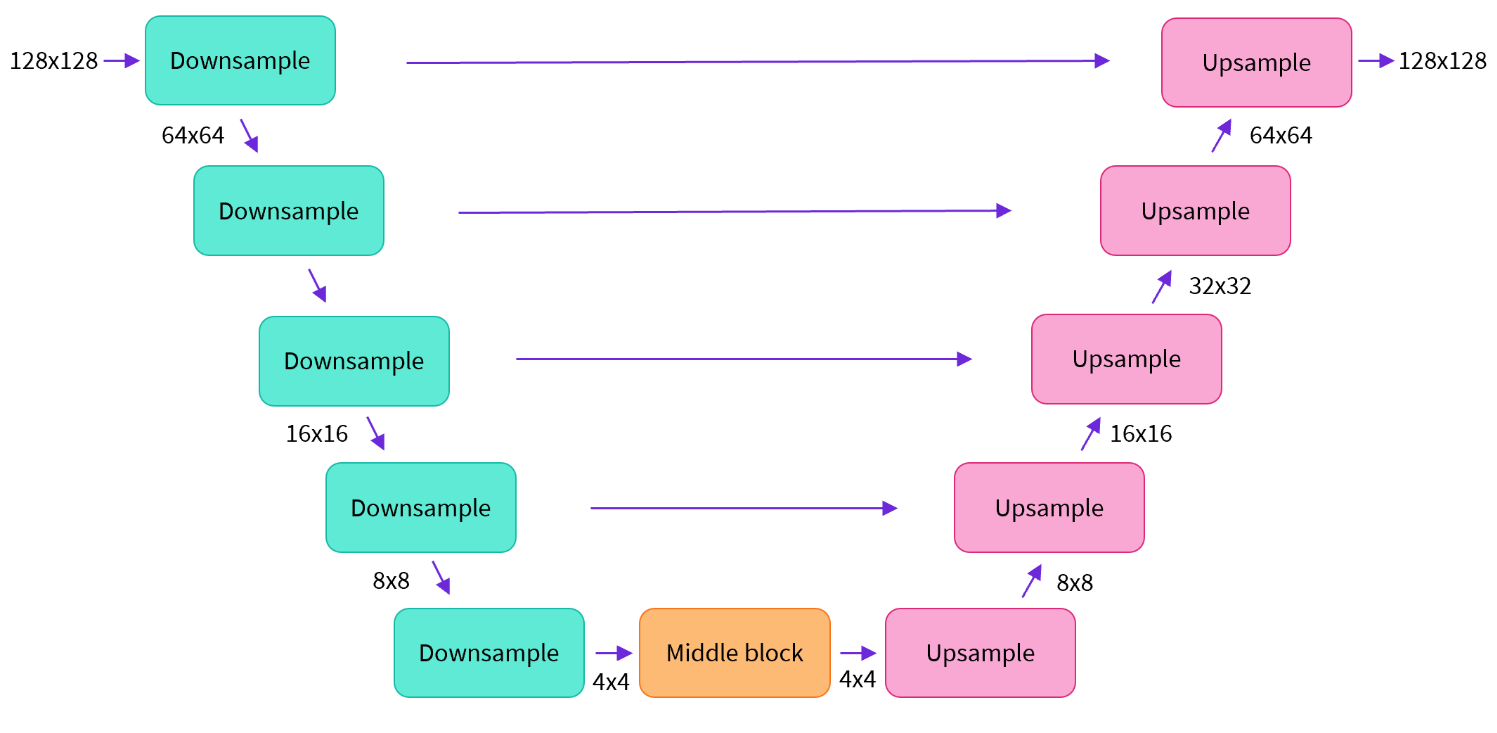

Figure from HuggingFace Diffusion Course

The UNet architecture has played a central role in the development of early diffusion models. It follows an encoder-decoder structure with skip connections, which allows it to capture both high-level and detailed spatial information. This works well in diffusion models since the dual capture allows the models to combine both visual semantics as well as fine-grained image detail to generate high quality images.

While effective in generating images, UNet has limitations in scalability and flexibility, especially when incorporating textual input. Its high memory usage and lack of modularity make it less suitable for handling multimodal interactions.

1.3 Latent Transformer-based Advances: DiT, Cross-DiT, SiT

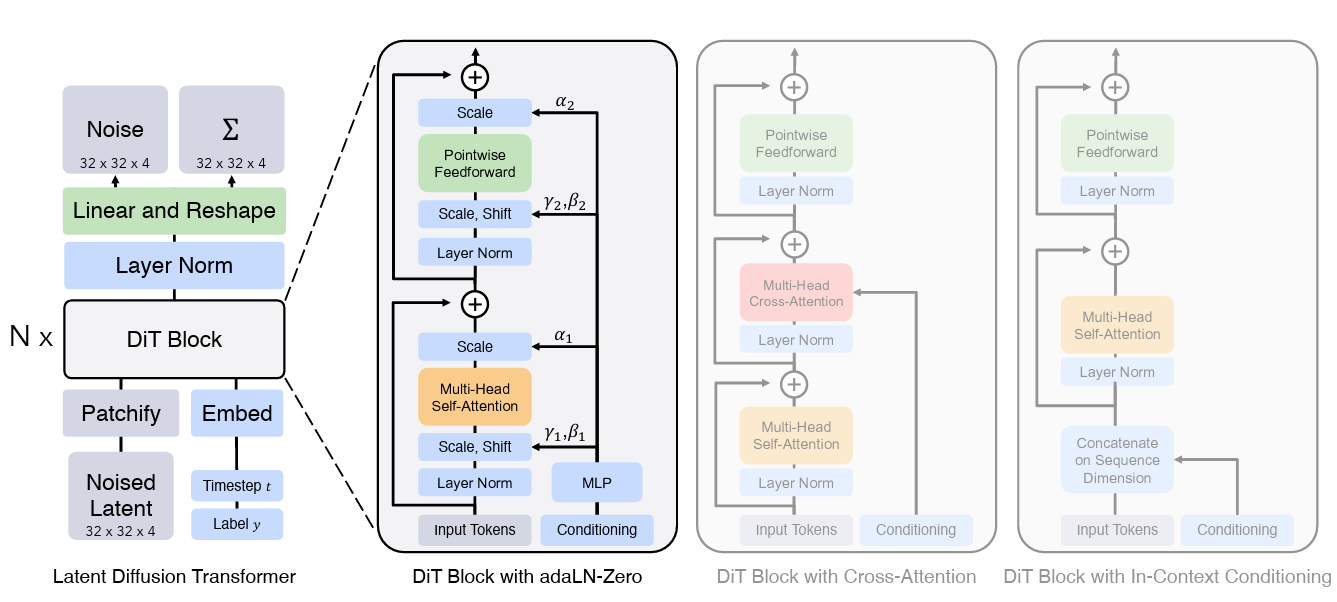

Figure from DiT paper [3].

To overcome the limitations of UNet, researchers attempted to replace the convolutional backbones of diffusion models with transformers, giving rise to the transformer-based diffusion model. One of the very first well-performing models, DiT (Diffusion Transformer, 2023), replaces the main backbone with a Vision Transformer (ViT) architecture [3]. Their results showed very good scalability as well as superior performance compared to most state-of-the-art diffusion models during that time. As such, many future papers on diffusion models reference and utilize DiT quite frequently. Another work, Cross-DiT, extends this idea by introducing cross-attention layers, enabling textual information to influence the image generation process. Lastly, in 2024, a new type of transformer-based diffusion model, SiT, built upon the DiT backbone architecture in terms of learning, objective function, and sampling. Instead of predicting noise at each time step, it predicts the trajectories between the noise and data, improving robustness and stability. Their results showed that SiT surpasses DiT uniformly with the same model structure and number of parameters [4]. Since then, SiT remained one of the top state-of-the-art diffusion models utilized in research.

In addition, to reduce the input size passed into the transformers, researchers utilize a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to encode input to a smaller latent space and decode output back to the original image dimensions (will be discussed further). This can be simply added to existing transformer diffusion models to improve their efficiency significantly. As a result, these types of diffusion models are termed latent diffusion models and are used in many papers such as REPA.

While transformer-based diffusion models have experienced rapid attention and improvement, they still suffer from some limitations. For example, when incorporating text or other modalities into these diffusion models, they usually merge the embeddings together into a single image embedding. This means that textual input attends to image features while modalities utilize shared weights, stripping the modalities of a lot of information. As a result, the expressiveness of the diffusion models are significantly limited.

1.4 Evaluating Diffusion Models

When evaluating diffusion models, there are various performance metrics to pay attention to. Usually, many diffusion model papers focus on generation quality to compare the models. The better the generation, the better the model. A mainstay metric used to evaluate generation quality for diffusion models is called the Frechet Inception Distance (FID) metric [5]. The basic idea is that we pass both the real image as well as the associated generated image into a pre-trained inception network to obtain feature vectors for both images. Then, we use the distance between the two vectors as a score to judge the similarity between the real image and the generated image. The smaller the score, the closer the generation is to the real image. Usually, many papers will utilize ImageNet, an image dataset, to calculate the FID score. Lastly, there was a future work that improved FID, called sFID, which was stated to more accurately measure the performance/differences between the real and generated feature vectors [6].

While FID is used as the main metric when comparing the performance of diffusion models, there are also other metrics used as well to compare generation variance and visual representation. For instance, Linear Probing is often used as a metric to judge how well a diffusion model’s internal visual representations are. While diffusion models are focused on generating realistic images, researchers have noticed that diffusion models also slightly learn visual semantics. Thus, to see how strong these representations are, we can use linear probing to freeze the output layer of the diffusion model and see how well the output embeddings can be classified in a pre-determined dataset (usually ImageNet) using a simple 3-layer neural network. If the classification accuracy is high, then the diffusion model has learned very strong visual representations and can differentiate images very well. Besides learning probing, researchers also utilize Inception Score (IS) to judge the generation diversity and quality of a diffusion model [7]. Similar to FID, the generated images are sent through an inception model to output a feature embedding. Then, they see if the feature embeddings can be used to easily classify images as well as how see many image classes are covered. The higher the IS score, the better the generation quality and diversity.

2. Stable Diffusion (Dec 2021) [8]:

This paper, “High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models” (https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.10752v2), addresses the high computational cost and slow inference of traditional diffusion models (DMs) while aiming to democratize high-resolution image synthesis.

2.1 Motivation

Diffusion models have achieved remarkable success in image synthesis. However, they typically operate directly in pixel space, which is computationally very demanding. Training these models can take hundreds of GPU days, and inference is slow due to the sequential nature of the generation process. This high cost limits their accessibility and practical application. The authors aim to reduce these computational demands significantly without sacrificing the quality and flexibility of DMs.

2.2 Method

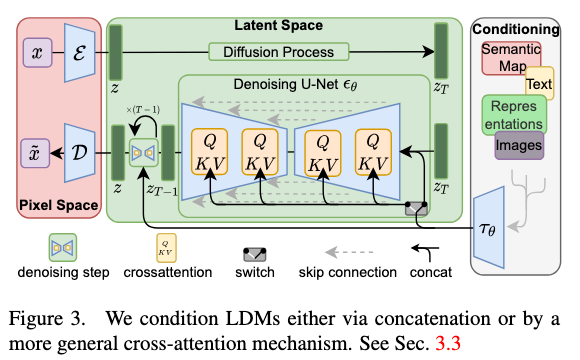

The core innovation is to apply diffusion models in a lower-dimensional latent space learned by a powerful pretrained autoencoder, terming this approach Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs). This method effectively decouples the perceptual compression from the generative learning process:

- First, an autoencoder is trained to learn a compressed latent representation of images that is perceptually equivalent to the pixel space but computationally much more efficient. This stage handles the high-frequency details and provides a compact representation.

- Second, a diffusion model is then trained in this learned latent space to generate new data. This two-stage approach allows the diffusion model to focus on the semantic and conceptual composition of the data within a more manageable space. To enable versatile conditioning, the authors integrate cross-attention mechanisms into the DM’s U-Net backbone. This allows the model to be conditioned on various inputs like text, semantic maps, or other images, making it suitable for tasks such as text-to-image synthesis, layout-to-image, and super-resolution. A key advantage is that the autoencoder is trained only once and can be reused for training multiple diffusion models for different tasks.

2.3 Results

The proposed Latent Diffusion Models demonstrate significant improvements in efficiency and achieve strong performance across various image synthesis tasks:

- Reduced Computational Cost: LDMs dramatically lower the training and inference costs compared to pixel-based DMs. For instance, they show that LDMs with downsampling factors of 4 to 8 (LDM-4, LDM-8) achieve a good balance between computational efficiency and high-fidelity image generation, significantly outperforming pixel-based DMs (LDM-1) trained with comparable compute.

- State-of-the-Art Performance: LDMs achieve new state-of-the-art results in tasks like class-conditional image synthesis (e.g., on ImageNet) and image inpainting. They also show highly competitive performance in text-to-image synthesis (e.g., on LAION-400M and MS-COCO), unconditional image generation, and super-resolution.

- Flexibility and Scalability: The cross-attention mechanism allows LDMs to handle diverse conditioning inputs effectively. The models can also generalize to generate images at higher resolutions than seen during training (e.g., up to 1024x1024 pixels) through convolutional sampling for spatially conditioned tasks.

- Qualitative and Quantitative Improvements: On datasets like CelebA-HQ, LDMs outperform previous likelihood-based models and GANs in terms of FID scores. The text-to-image models are shown to be on par with much larger contemporary models while using fewer parameters.

2.4 Analysis:

This paper introduces a method to make high-resolution image synthesis more computationally efficient. The key idea is to apply diffusion models (DMs) in a compressed latent space of a pretrained autoencoder, rather than directly in pixel space. This approach, termed Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs), significantly reduces computational demands for training and inference while preserving the quality and flexibility of DMs. The authors demonstrate that by training DMs on this latent representation, they can achieve a near-optimal balance between complexity reduction and detail preservation. Furthermore, they incorporate cross-attention layers into the model architecture, enabling LDMs to function as powerful and versatile generators for various conditioning inputs like text or bounding boxes, achieving state-of-the-art results on tasks such as image inpainting, class-conditional image synthesis, and text-to-image synthesis.

3. Stable Diffusion 3 (Mar 2024) [9]:

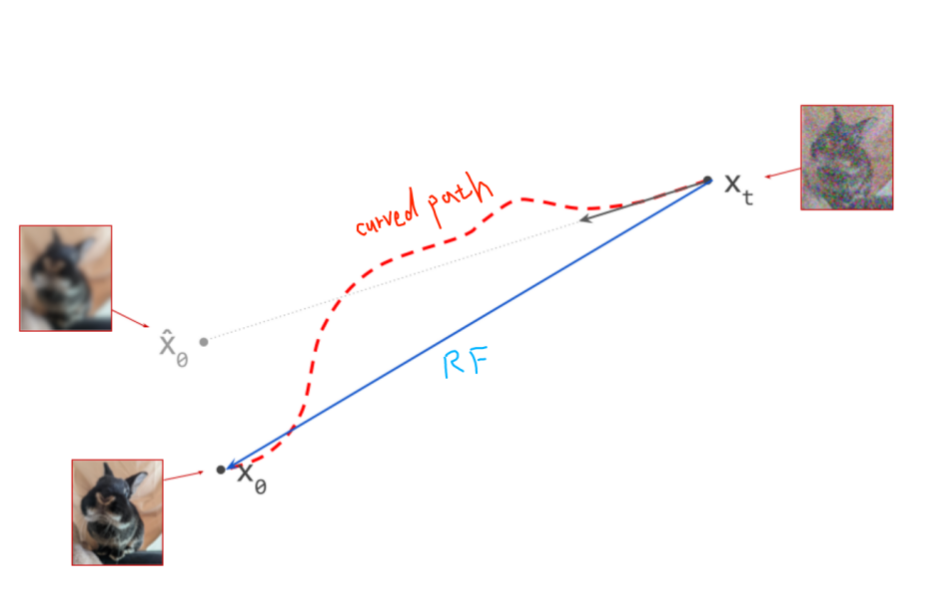

3.1 Diffusion Process: Curved Path and Its Drawbacks

Figure from The Paradox of Diffusion Distillation (https://sander.ai/2024/02/28/paradox.html).

Traditional diffusion models follow a curved transition path between the noise distribution and the data distribution. This non-linear mapping requires a large number of sampling steps, resulting in slow generation speeds and increased chances of error accumulation. These limitations restrict the practical scalability of diffusion-based image synthesis.

3.2 Rectified Flow: A Straighter Path

Stable Diffusion 3 addresses these limitations by introducing Rectified Flow (RF), a method that defines the diffusion trajectory as a straight-line interpolation between noise and data.

This modification significantly speeds up sampling and reduces the likelihood of cumulative errors.

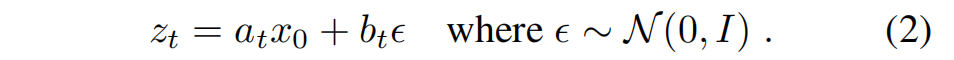

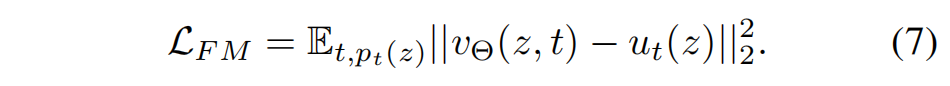

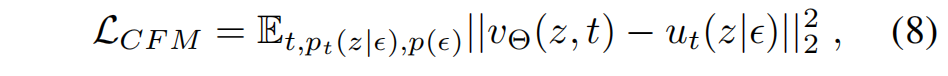

Training Objective

Initially, the model is trained to predict the velocity vector along this path and the flow matching objective is:

Later, the objective is reformulated as a noise prediction task, making training more tractable and efficient. The final conditional flow matching objective becomes:

where it measure the distance between predicted noise and true noised added in the forward pass.

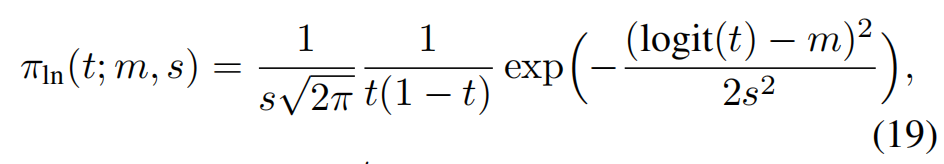

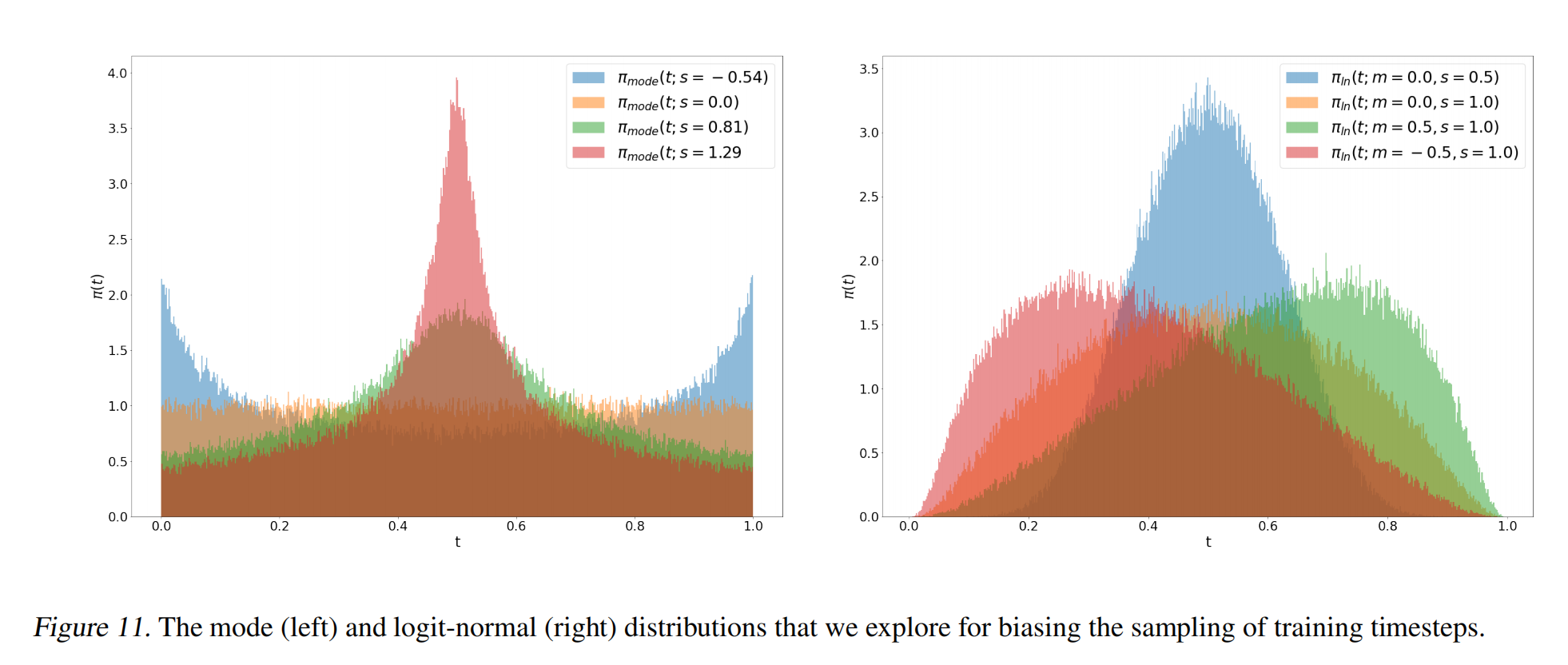

3.3 Logit-Normal Sampling

Instead of sampling timesteps uniformly, SD3 uses a logit-normal distribution to select timesteps during training:

This strategy emphasizes the intermediate timesteps—those that are more challenging and informative—while reducing focus on the endpoints, which are easier to denoise.

This targeted learning approach enhances both the efficiency and generalization capability of the model.

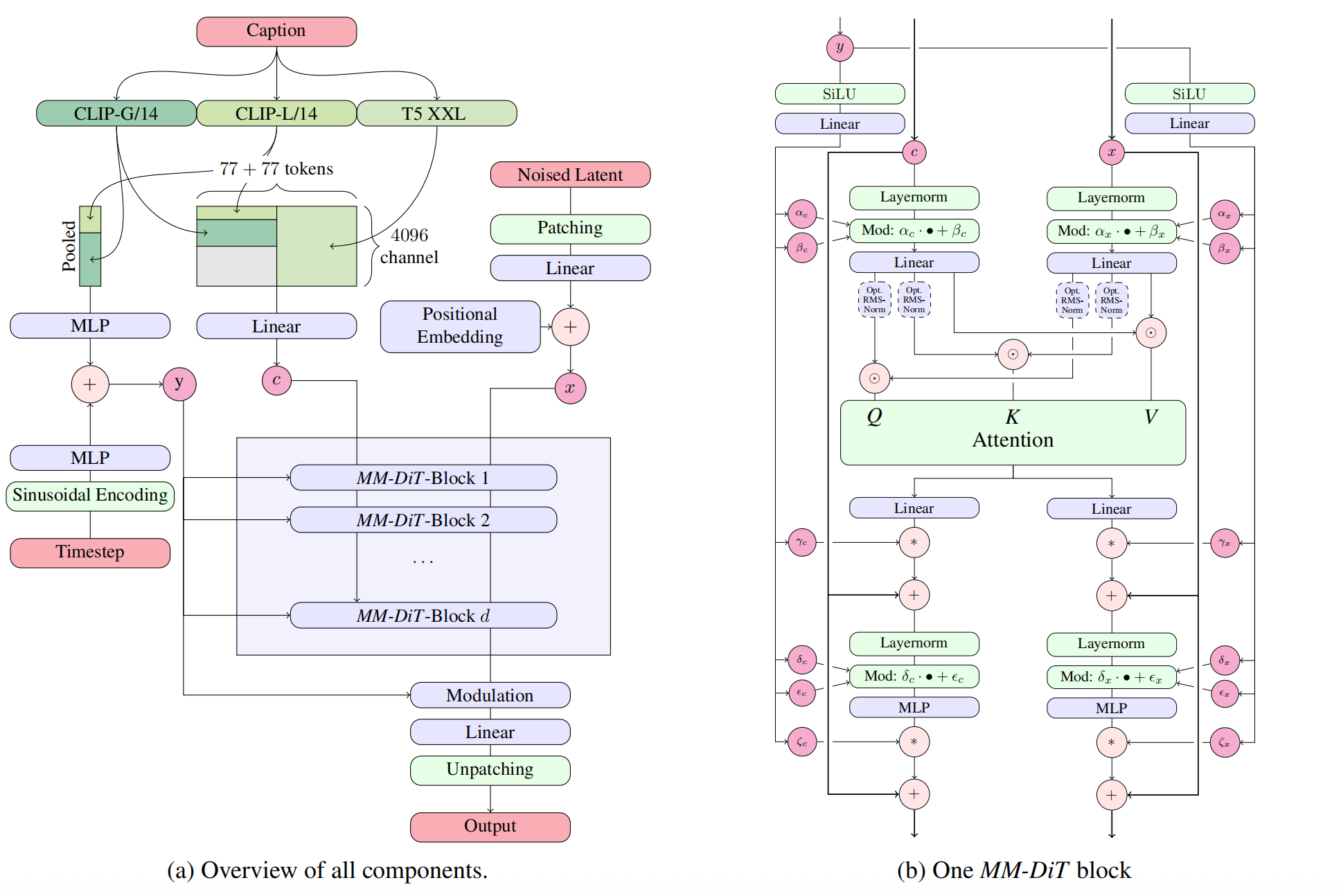

3.4 Architecture Overview

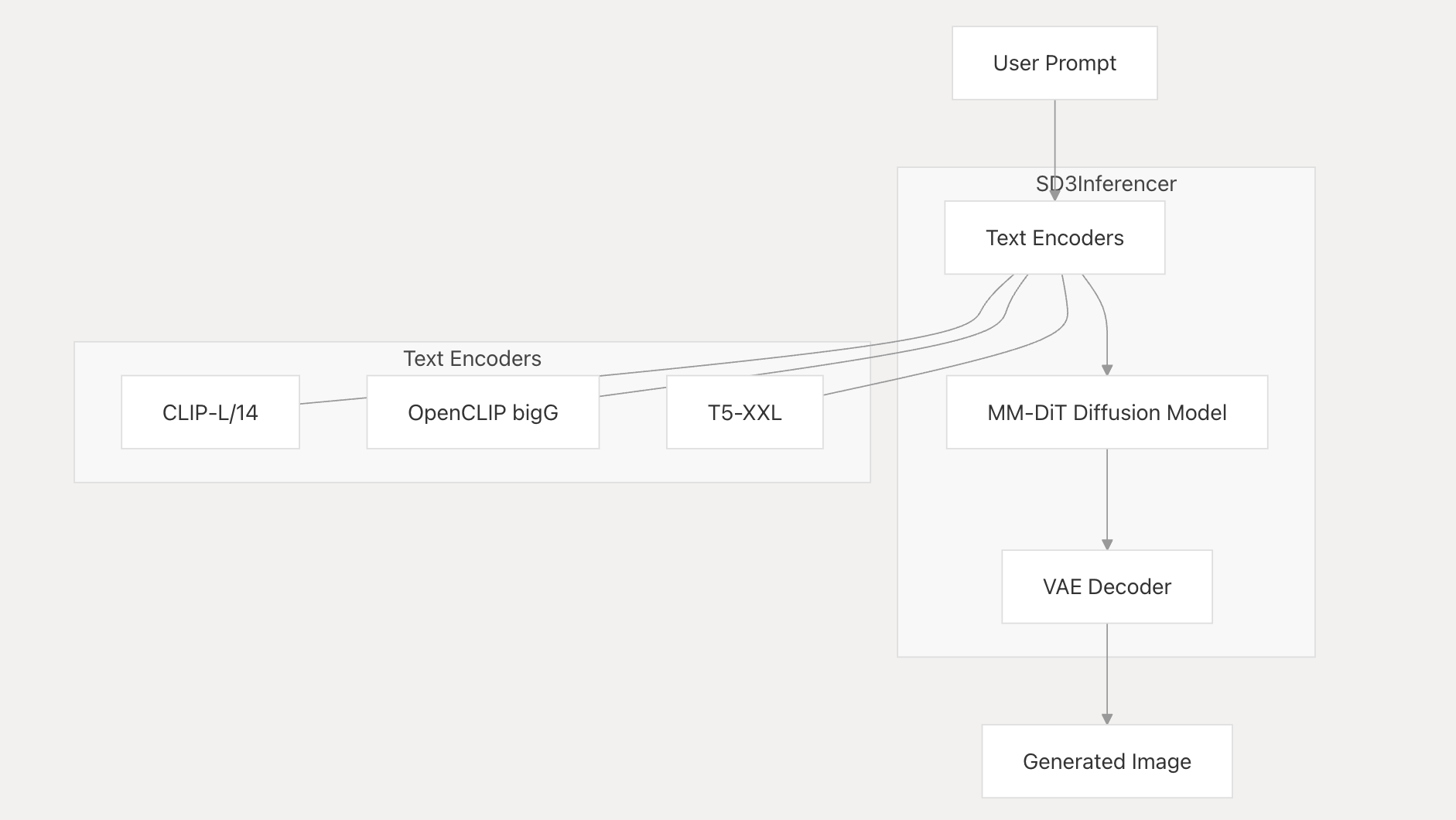

Figure from Stable Diffusion 3 paper (https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.03206).

The architecture of SD3 introduces several key components that enable effective multimodal generation:

-

Text Input: Text captions are processed using three encoders—CLIP L/14, OpenCLIP bigG/14, and T5 XXL. These produce two types of text representations: a coarse pooled output vector and a fine-grained channel-wise context tensor.

-

Image Input: The input image, after being encoded into a latent representation by a pre-trained autoencoder, is downsampled using 2x2 patches, flattened, and embedded into a token sequence with positional encodings.

-

MM-DiT Block: Text and image streams are processed using separate transformer weights. These modalities are combined by concatenating their token sequences and applying joint self-attention. Additionally, learnable modulation parameters derived from the text input are used to scale and shift intermediate representations.

-

Final Output: After passing through multiple MM-DiT blocks, the joint representation is transformed via linear layers, reshaped (unpatched), and used to predict the noise component.

3.5 Training Strategy

The training of SD3 follows a structured pipeline:

-

Data Preprocessing: The training dataset includes images from ImageNet and CC12M. Filters are applied to remove sexual content, low-quality images, and duplicates. Captions are a mix of 50% original human-written and 50% synthetic text generated by CogVLM.

-

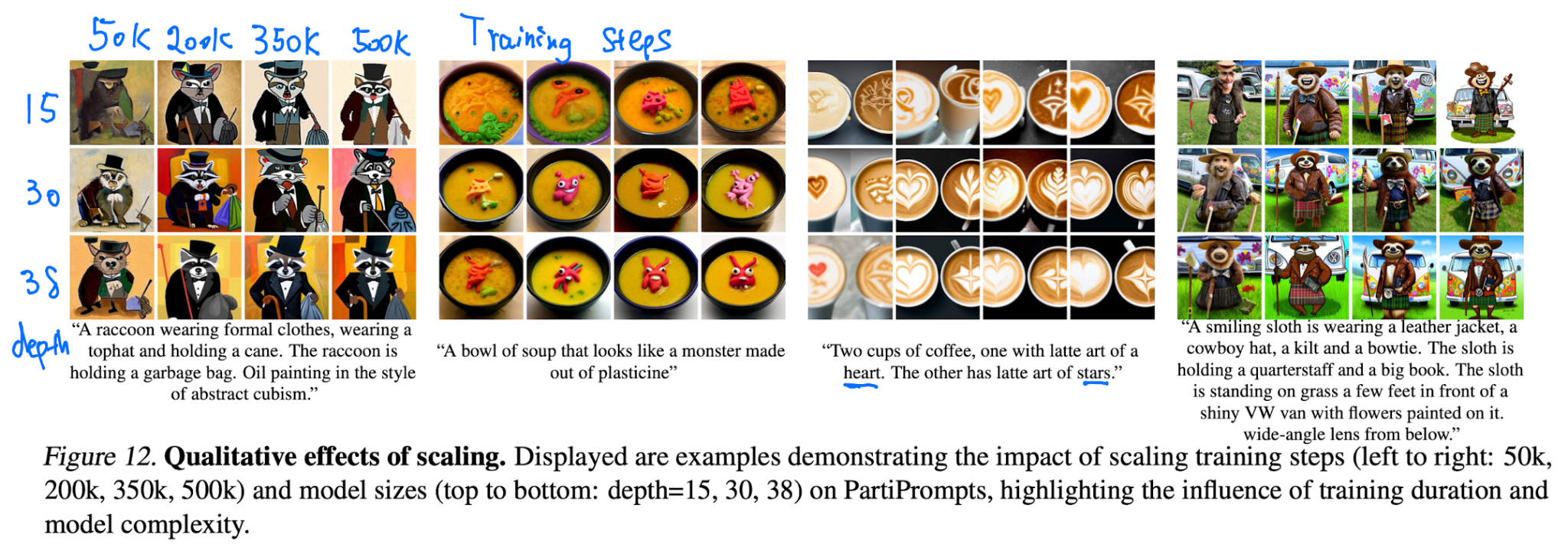

Pretraining: Initial training is conducted on low-resolution (256×256) images. Extensive scaling studies show consistent performance improvements as the number of parameters increases, reaching up to 8 billion.

-

Fine-tuning: The model is further trained on high-resolution images (1024×1024) with mixed aspect ratios. Techniques like mixed precision training, QK-Normalization, and adaptive positional encoding ensure stability and efficiency. Resolution-dependent timestep shifting is applied to balance denoising difficulty across different scales.

-

Alignment: Final alignment is achieved using Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) and Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA), which enhance visual quality and prompt fidelity, including better spelling and compositional alignment.

3.6 Evaluation and Insights

SD3’s performance was rigorously evaluated using both standard quantitative metrics like CLIP score, FID, T2I-CompBench, and GenEval, as well as human preference ratings.

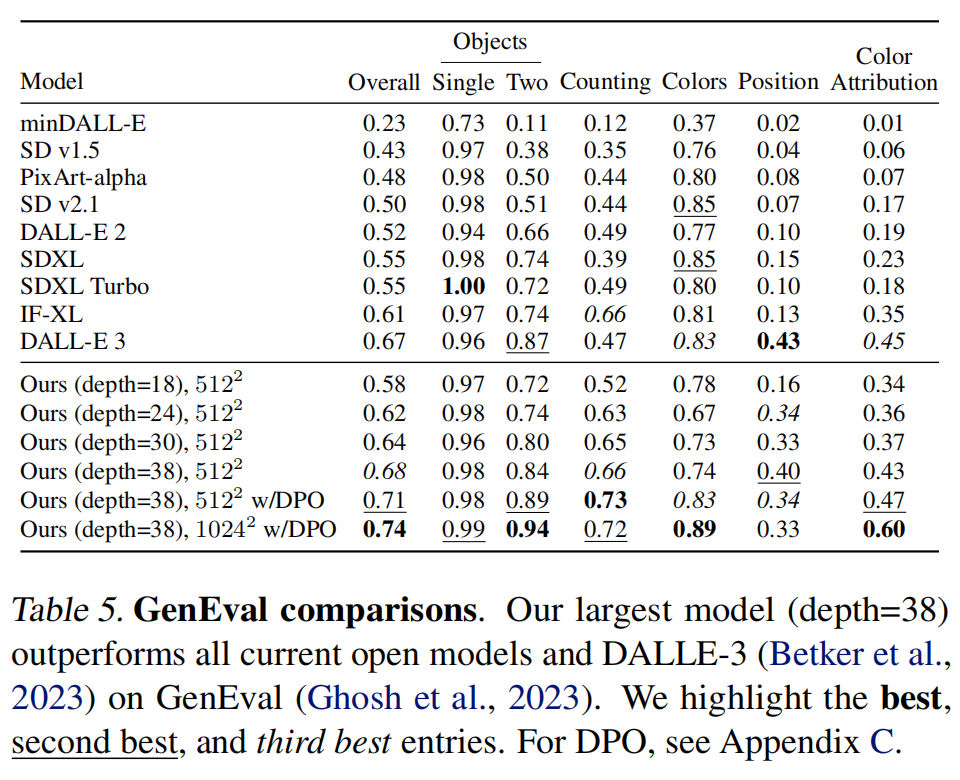

3.6.1 Benchmark Result

The largest variant of SD3 (depth=38 with DPO) achieves state-of-the-art performance across all major benchmarks, outperforming both open-source and closed models such as DALLE-3. Evaluation metrics include CLIP score, FID, T2I-CompBench, and GenEval.

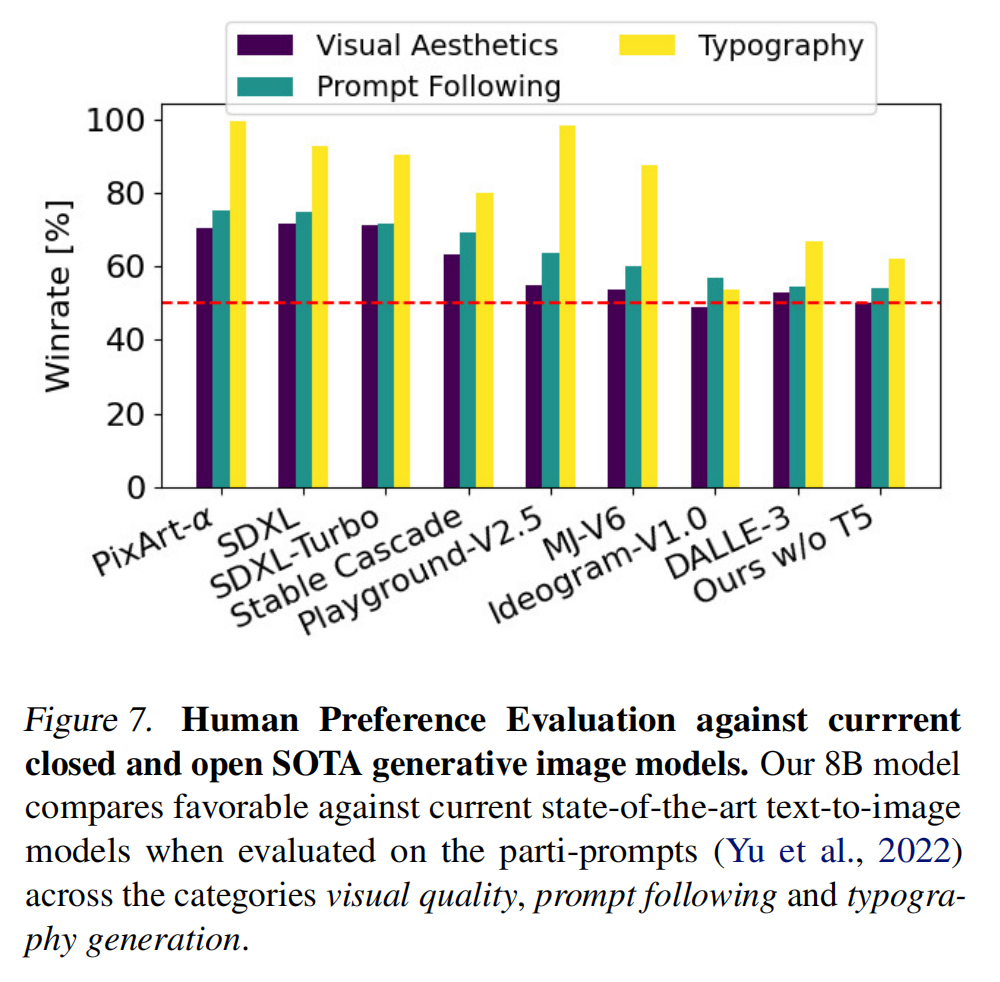

3.6.2 Human Evaluation

In blind pairwise comparisons, human raters preferred SD3-generated images more than 50% of the time across various prompts. SD3 showed particular improvements in color accuracy, spatial coherence, and semantic relevance to text prompts.

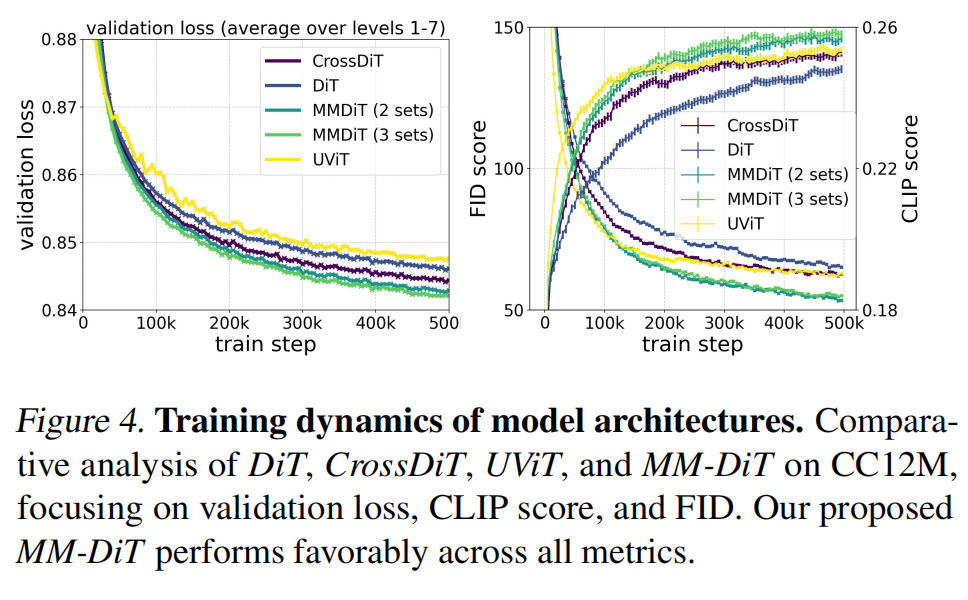

3.6.3 Architecture Insights

Empirical studies reveal that increasing the number of latent channels (e.g., to 16) significantly improves image fidelity and reconstruction. MM-DiT consistently outperforms previous transformer-based architectures like DiT, CrossDiT, and UViT. Furthermore, QK-Normalization plays a crucial role in preventing instability in attention logits, thus enabling reliable training under mixed precision.

3.6.4 Sampling Efficiency and Scaling

Larger SD3 models not only generate higher-quality outputs but also require fewer sampling steps due to better alignment with the rectified flow objective. Increasing both model depth and training duration correlates with reduced validation loss and improved perceptual quality.

3.7. Community Impact and Future Work

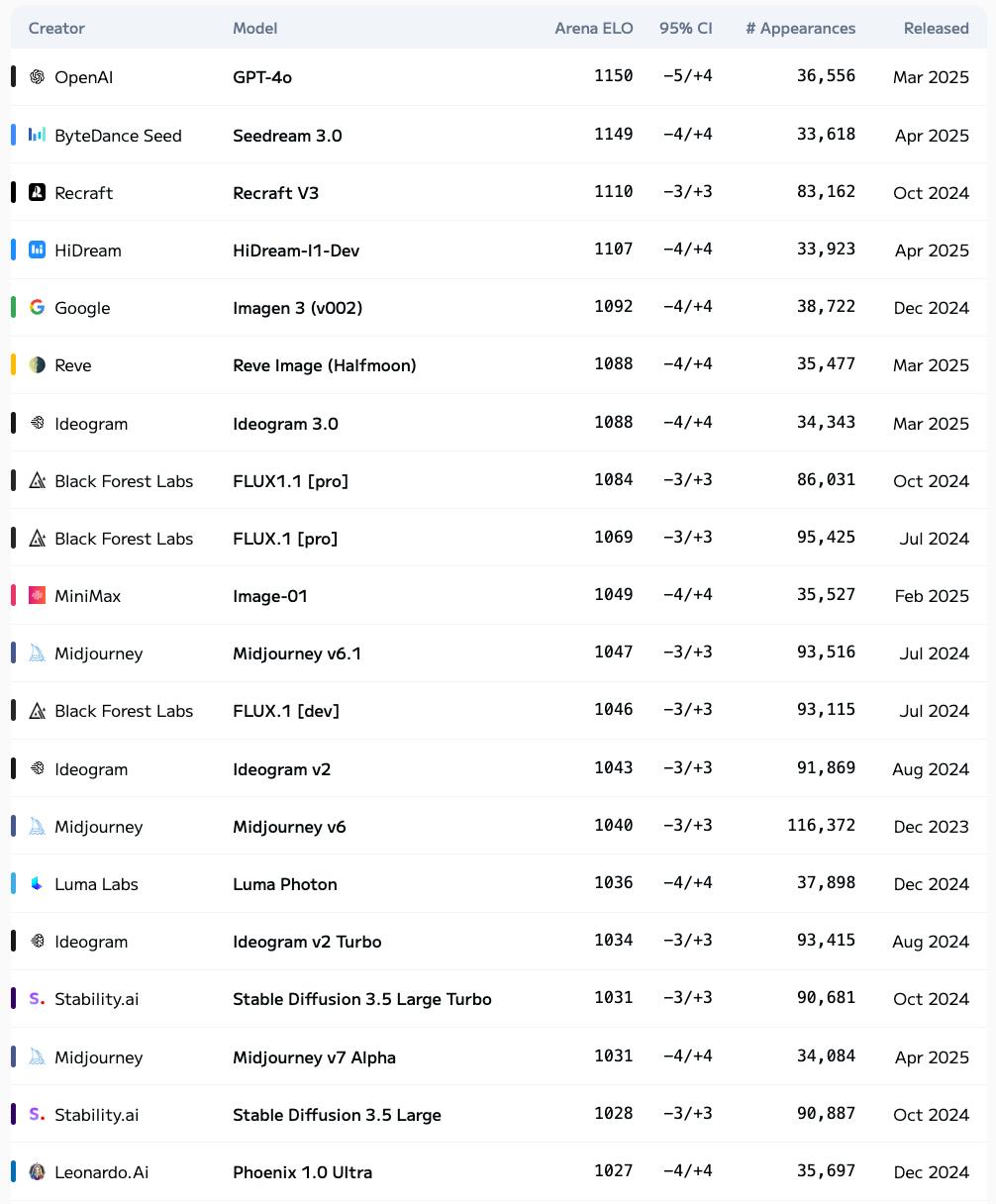

3.7.1 SD3 in 2025

As of May 2025, SD3.5 (released in October 2024) ranks 17th on the Hugging Face text-to-image leaderboard. Despite the growing dominance of closed-source models, SD3’s open-source release remains a cornerstone for transparency and research reproducibility in generative AI.

3.7.2 Multimodal Extensions

MM-DiT is well-suited for expansion into other multimodal tasks such as text-guided image editing, inpainting, and video generation. These tasks present challenges such as aligning multiple modalities (e.g., audio, video, text) and maintaining temporal consistency in sequential content.

Potential solutions include adding dedicated temporal transformer layers, enforcing frame-to-frame coherence through explicit losses, and using low-rank adapters to efficiently adapt pretrained models.

3.8 Analysis

A key strength of this work lies in its systematic approach to scaling. The researchers demonstrate that their MM-DiT architecture exhibits predictable scaling trends, meaning that increasing model size and training data leads to consistent improvements in image quality and prompt adherence. Their largest 8-billion parameter model is shown to outperform prominent open-source and proprietary models on several benchmarks, including human preference evaluations, particularly in areas like typography and complex prompt understanding. The paper also details several crucial technical innovations, such as improved autoencoders, the use of synthetically generated captions to enrich training data, and QK-normalization for stabilizing training at high resolutions.

Furthermore, the study provides valuable insights into the practical aspects of training large-scale generative models. The authors address data preprocessing meticulously, including filtering undesirable content and employing deduplication techniques to mitigate training data memorization. They also explore methods like Direct Preference Optimization (DPO) for fine-tuning, and introduce flexible text encoder usage at inference time, allowing a trade-off between performance and computational resources. The comprehensive nature of the experiments and the public release of code and model weights contribute significantly to the open research landscape in generative modeling.

3.9 Code Implementation

Stability AI released implementation code for inference. The link is https://github.com/Stability-AI/sd3-ref.

The architecture of the codebase is below:

The SD3 implementation consists of the following key components:

- Text Encoders: Three separate models process text prompts:

- OpenAI CLIP-L/14: Processes text prompt for general understanding

- OpenCLIP bigG: Similar to SDXL’s text encoder for enhanced comprehension

- Google T5-XXL: Provides additional text understanding capabilities

- MM-DiT (MultiModal DiT): The core diffusion model that generates image latents

- VAE Decoder: Transforms latent representations into visible images (16 channels, similar to previous SD models but without postquantconv)

An sample code for forward process in MM-DiT is shown below:

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor, t: torch.Tensor,

y: Optional[torch.Tensor] = None,

context: Optional[torch.Tensor] = None) -> torch.Tensor:

"""

Forward pass of DiT.

x: (N, C, H, W) tensor of spatial inputs (images or latent representations of images)

t: (N,) tensor of diffusion timesteps

y: (N,) tensor of class labels

"""

hw = x.shape[-2:]

x = self.x_embedder(x) + self.cropped_pos_embed(hw)

c = self.t_embedder(t, dtype=x.dtype) # (N, D)

if y is not None:

y = self.y_embedder(y) # (N, D)

c = c + y # (N, D)

context = self.context_embedder(context)

x = self.forward_core_with_concat(x, c, context)

x = self.unpatchify(x, hw=hw) # (N, out_channels, H, W)

return x

Explanation:

The forward pass through MM-DiT follows these steps:

- Input latents are embedded into patches and positional embeddings are added

- Timestep is embedded and combined with class embeddings if present

- Context is processed through the context embedder

- The embeddings pass through a series of transformer blocks with context mixing

- The final layer processes the output with additional conditioning

- The result is unpatchified back to the original spatial dimensions

For detailed explanation on the codebase, you can check out DeepWiki at https://deepwiki.com/Stability-AI/sd3-ref

In addition, I prepare a inference demo code on Google Colab which you can also take a look:

https://colab.research.google.com/drive/1TGiPaS8PDBbc-lZon1X_zR7M4Xv7PFSY#scrollTo=NZ00MJeYnTnE

4. REPA: Representation Alignment (Oct 2024) [10]

REPA is a simple regularization technique utilized during pre-training to align the visual representations of latent transformer-based diffusion models to the visual representations of pre-trained unsupervised vision transformers. Even though the technique is simple, it improves the generation quality and convergence speed of transformer-based diffusion models significantly, performing better than most state-of-the-art diffusion models. After publication, REPA has achieved moderate success, being cited and utilized as benchmarks in various papers.

4.1 Motivation

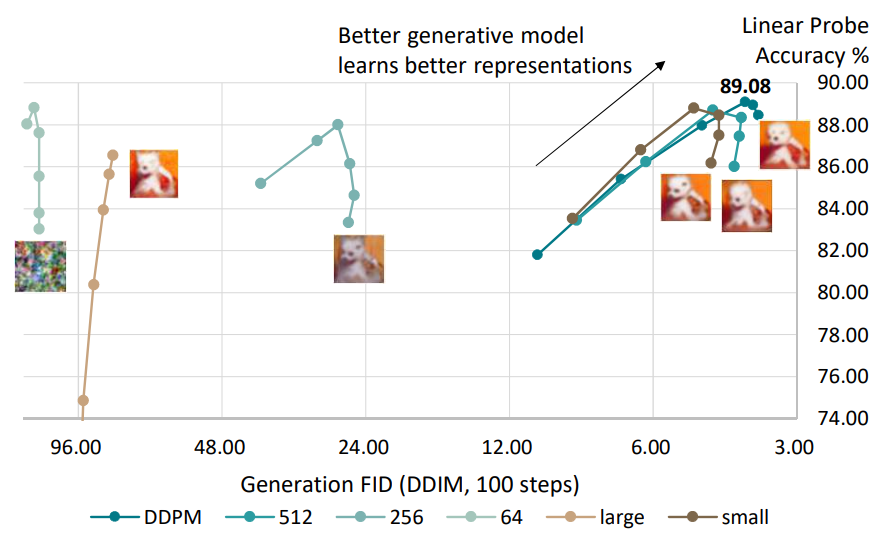

When analyzing the characteristics of diffusion models, the authors discovered a paper that uncovered an interesting correlation between generation quality and internal visual representation. This paper, titled Denoising Diffusion Autoencoders are Unified Self-supervised Learners, found that diffusion models learn discriminative features in hidden states similar to vision encoders [11]. However, because diffusion models are trained to optimize generation rather than vision representation, these hidden states are not as strong. In addition, they found that models with better generation had better vision representation. This led the REPA authors to observe that “The main challenge in training diffusion models stems from the need to learn a high-quality internal representation h”.

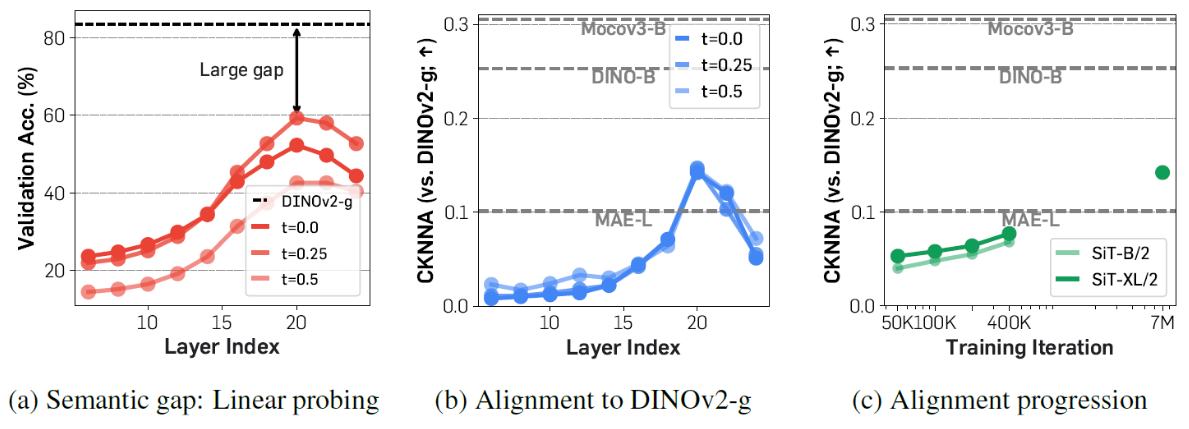

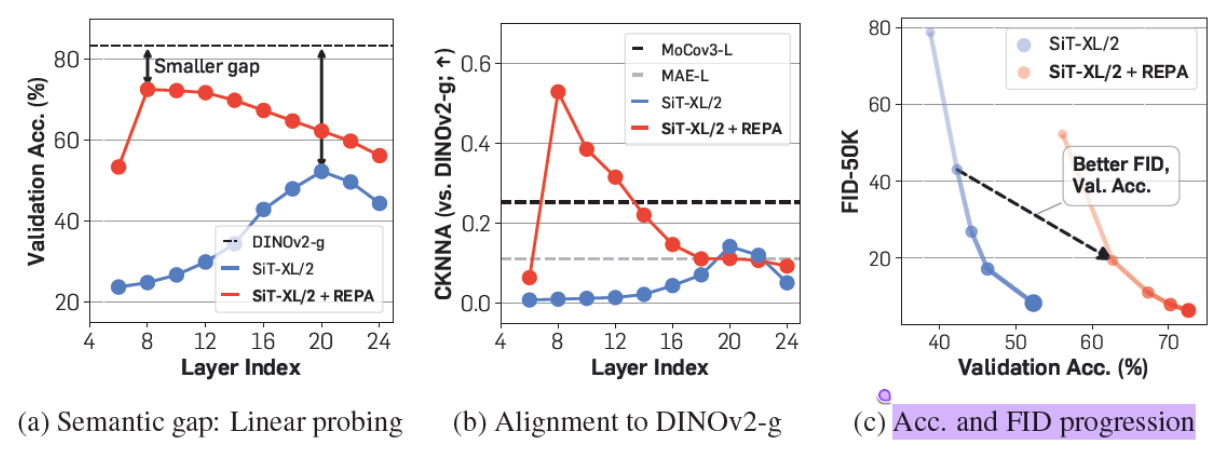

If the diffusion model’s internal representations have high vision representation, then their performance will improve significantly. To ground their hypothesis, the authors first observed how the internal representations of current state-of-the-art diffusion models (such as SiT) compared to the representations of the best vision transformers (such as DINOv2). Vision transformers are self-supervised and trained to focus on having good vision representation and classify images, making them a good comparison to test vision representation. From their brief survey, the authors found a significant gap between the vision representations, with SiT having very poor representation compared to DINOv2. While longer training sessions resulted in slightly better representation, diffusion models in general had poor vision representation compared to vision transformers.

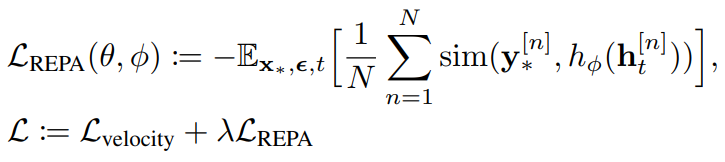

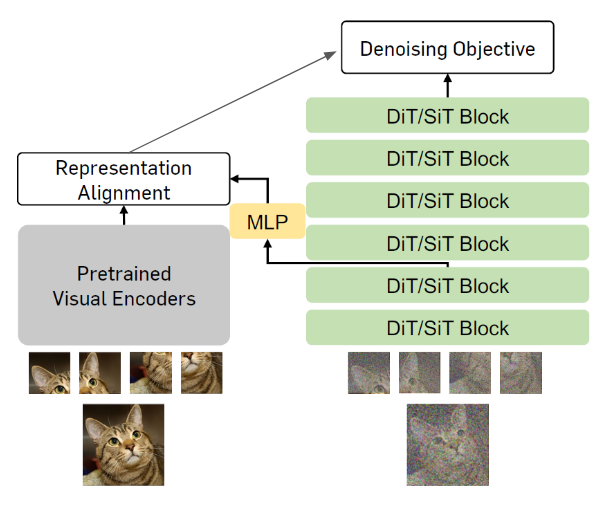

4.2 Approach

From their study, the authors’ main goal was to improve the internal vision representation of diffusion models. To do this, they proposed REPA, a pre-training regularization technique that encourages diffusion models to improve their vision representation. The idea is to calculate the similarity between the image embeddings of a pre-trained vision transformer and the internal representations of each layer of the diffusion model to regularize the objective function. Of course, the two embeddings are in different dimensions at first. Thus, the authors pass the internal representation through a MLP to give the embedding the same dimensionality as the external embedding. Then, they utilize a simple similarity function such as cosine-similiarity or cross-entropy to compare the two before adding it to the final objective function.

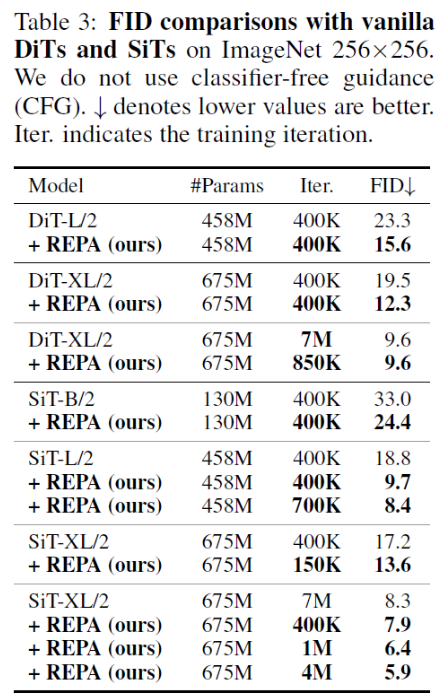

4.3 Evaluation

The authors evaluated REPA by pre-training latent transformer diffusion models (mainly DiT and SiT) with various different vision transformers that provide the external representations for REPA. From their results, they found that REPA significantly improves the vision representation of diffusion models in general, surpassing most state-of-the-art models.

In addition, both generation quality and convergence improve significantly, with models requiring only around 25% of the original amount of training to reach the same performance.

4.4 Conclusion and Future Works

The appeal of REPA is not only in its performance boost, but also its flexibility and simplicity. It can be used with any vision transformer and transformer diffusion model, making it very accessible and usable. In addition, the regularization can be customized and applied to as many or as few layers as possible. Overall, it’s a simple technique with enormous benefits.

After the paper was released at the end of 2024, REPA has received decent success, as it has been cited by 83 papers (based on Google Scholar). Many of these papers reference it in their related works, with others utilizing it as a state-of-the-art benchmark for their work. In addition, various researchers stated that when they attempted to replicate the REPA paper’s results, they found that REPA performed even better than what was reported. Overall, it seems like REPA is slowly being adopted and utilized in the academic field of transformer diffusion models.

4.5 Analysis

With such a simple regularization strategy, REPA can improve the performance of transformer diffusion models significantly. This poses the question: Why does REPA improve the performance so much? Within the paper, the authors used empirical evidence as their motivation, but are also unsure of the effects vision representation have on diffusion models. Our opinion is that the authors of REPA may have happened to find a critical component of transformer diffusion models. Somehow, vision representation plays a very crucial role within diffusion models in generation quality. Perhaps it improves the initial layers of the transformer, giving the model much clearer coherent high-level semantics and information. This then translates to fine-level detail, which diffusion models already perform well at.

In addition, REPA can probably be utilized in other modalities for generation AI as well. For example, the authors of the paper suggested using REPA for video generation. In addition, we could probably use REPA in other applications such as audio generation and multi-modal diffusion models. However, it is imperative to first check if good representation is equivalent to good generation for these modalities, as this might only be a characteristic for image generation. Perhaps for other modalities like audio, the internal representations are formed differently. Regardless, utilizing REPA for other modalities is a very interesting idea for future works.

While the REPA paper thouroughly discusses the impressive results REPA has, it doesn’t state any limitations or weaknesses of REPA. One obvious weakness is that the use of REPA will require additional resources due to the use of an additional vision transformer. However, this is all done during pre-training, so REPA will not impact inference time or resource consumption whatsoever. Another weakness of REPA was mentioned in another paper (REPA-E), that stated that REPA is bottle-necked by the latent space features of the VAE [12]. Because these VAEs are pretrained and frozen, there exists a limit to how much better the vision representation can become. The paper then discusses their own solution to this problem, which will be addressed in the next section of this technical blog. Lastly, REPA requires us to have a good pre-trained vision transformer to use. However, if we were dealing with out-of-distribution data or poorly supported fields, then there might not be a vision transformer for us to use. Despite these flaws, there doesn’t seem to be any signifcant negatives to REPA. The paper showed many impactful results and released working code for other researchers to use. However, when experimenting with the code in Google Cloud Platform, we did not have enough resources to run REPA and test its generations.

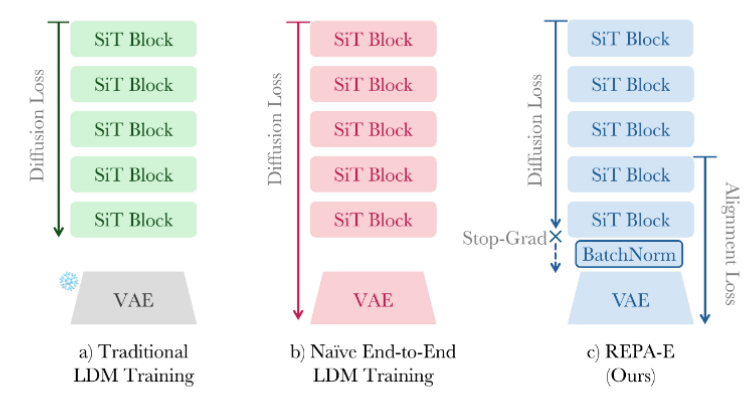

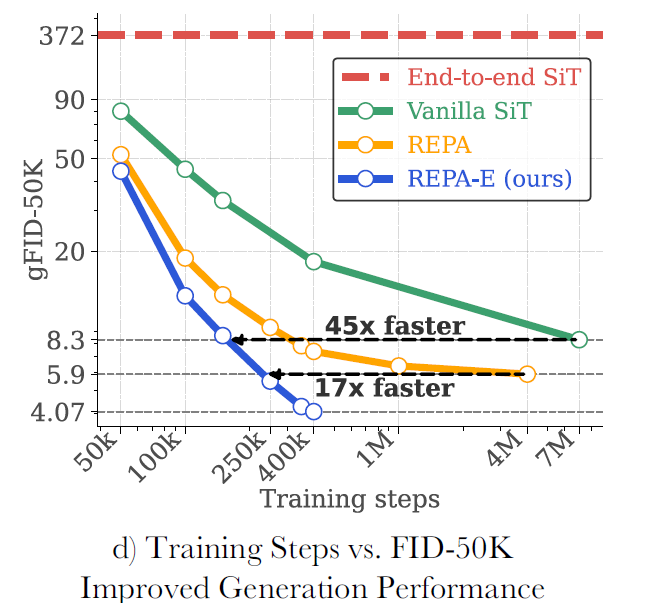

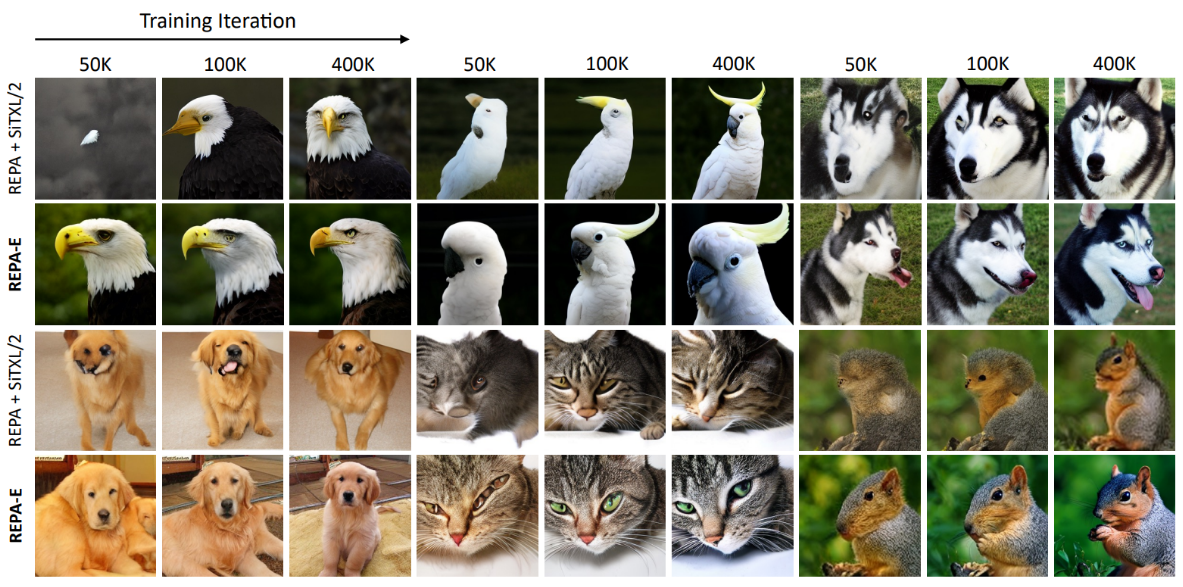

5. REPA-E: End-to-End Representation Alignment (Apr 2025) [12]

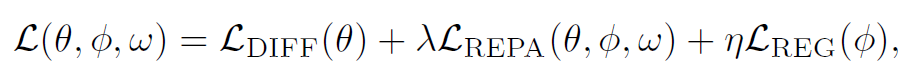

REPA-E is a recently published paper that builds upon REPA to enable end-to-end learning for latent transformer-based diffusion models by training the VAE as well as the diffusion model at the same time. Their results show even greater performance, achieving 17x faster convergence than REPA and setting a new state-of-the-art.

5.1 Motivation

Traditionally, latent diffusion models are trained with a pre-trained VAE, which only updates the generator network. Although end-to-end training is preferred in most deep learning scenarios, previous results showed that naiively training both the diffusion model and VAE together yields poor results. The authors suggest this is due to the model making the VAE latent space simpler to minimize the objective function, hurting the generation quality of the model. Lastly, as mentioned in the REPA section, they found that REPA was bottlenecked by the pre-trained VAE latent space features. When the authors backpropagated the REPA-loss, they noticed that the vision representation of the VAE improved by around 25%. Motivated by these findings, the authors proposed to perform end-to-end training using REPA loss instead of purely using diffusion loss.

5.2 Approach

The authors’ approach is to train both the diffusion model and VAE at the same time using the original diffusion loss plus REPA loss and VAE regularization loss. While REPA was originally only applied to the diffusion models, the authors apply it to the VAE to update its parameters as well. In addition, they add regularization loss to the VAE to ensure that the end-to-end training process does not degrade its performance. By adding more regularization, the authors allow the VAE model to train along the diffusion model. This means that not only will the diffusion model have higher visual representation (which equates to better performance), but the VAE will also have expressive latent space features that are optimized for generation tasks.

5.3 Evaluation

To evaluate REPA-E, the authors mainly use SiT and its varying model sizes as their main diffusion model. As for the external representation encoders for REPA, they chose to utilize DINOv2 for most of their experiments. Finally, they used SD-VAE as their VAE. From their results, the authors showed that REPA-E outperformed REPA substantially, with FID (generation quality, lower = better) being reduced by at least 40% and convergence being 17 times faster. In addition, using different represention encoders yielded consistent performance improvements.

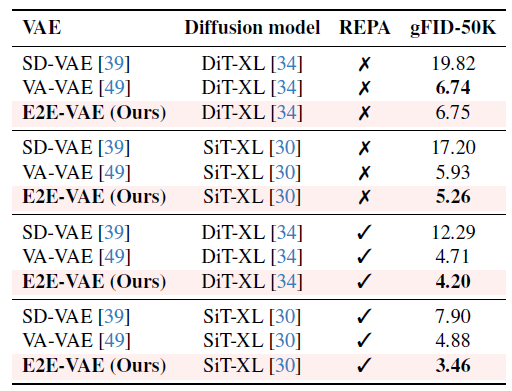

Besides the diffusion model, the authors also found that the tuned VAE also performed very well. While tuning a pretrained VAE does improve performance slightly, REPA-E can train a VAE and diffusion model by scratch and still outperform REPA. They then focused on evaluating the performance of their tuned VAE, which they named E2E-VAE. One thing they noticed was that once tuned, E2E-VAE could be used as a drop-in replacement for traditional diffusion model training. By freezing the VAE and training only the diffusion model, the authors found that the diffusion models trained with E2E-VAE outperformed diffsion models trained with state-of-the-art VAEs.

Then, when comparing the downstream generation performance of E2E-VAE to other state-of-the-art VAEs, they found that E2E-VAE consistently performed the best over a variety of metrics. From their results, the authors confidently concluded that they have achieved a new state-of-the-art for both latent diffusion models and VAEs.

5.4 Conclusion and Future Works

By expanding REPA to train both the diffusion model and the VAE, the authors achieved superior performance and convergence at a very low cost. In addition, they published their code and uploaded their checkpoints onto HuggingFace for researchers to replicate their results. However, similar to REPA, we do not have enough GCP resources to experiment with REPA-E. Although the authors don’t mention any future works, it’s clear that REPA-E will have a big impact in the future of latent diffusion models.

5.5 Analysis

Overall, REPA-E improves upon REPA and yields impressive results. The authors evaluated their work really well, testing different VAEs and representation encoders, comparing REPA-E with current state-of-the-art models, and having very clear results. A problem with the paper is that it doesn’t discuss limitations and future works. The authors should have stated some future works that could inspire further research. For example, expanding REPA-E for different modalities such as image-text and audio input would be interesting to see (similar to what was done for REPA).

In addition, it might be worth exploring why REPA-E further improves the performance of latent diffusion models. While better latent features spaces and vision representation emperically gives better results, it’s still not really understood why this is happening exactly. Does REPA-E improve both VAE and diffusion model performance, or does it only significantly improve the VAE’s performance, which improves the performance of the model in general? If this research of representation alignment continues to grow, it’s imperative to analyze and understand what exactly is happening to further improve it. Our opinion is that before, pretrained VAEs might not align well with the denoising task of diffusion models. By adding it into the training process, we can tune it to allow the transformer network to achieve superior vision representation. So while REPA-E unlocks the true potential of latent diffusion models, the REPA regularization is doing a lot of the heavy lifting. However, at this point, there might not be any more extensions to exploit diffusion model vision representation. Perhaps targetting the pretrained vision transformer to focus on generation-based vision representation might be a future work. Lastly, since this paper was only recently published, it would be interesting to see if the authors will add future addendums to add onto their work.

6. Comparing Methods

The evolution of diffusion models discussed in this report reveals distinct philosophical approaches to advancing generative AI. By comparing these methods, we can trace a clear trajectory from foundational architectural shifts to more nuanced, fundamental optimizations.

Initially, Stable Diffusion marked a pivotal moment by introducing the Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to operate in a compressed latent space. This fundamental shift away from the computationally intensive pixel space addressed critical issues of inference speed and resource cost. While the original U-Net backbone has since been largely superseded, the latent space concept established by Stable Diffusion remains a cornerstone of modern, efficient diffusion models, including DiT and SiT.

The next wave of innovation saw a divergence in architectural design. While Stable Diffusion 3 and SiT both build upon a transformer backbone, their objectives differ. SD3 introduces a complex, multimodal architecture (MM-DiT) and a new diffusion trajectory (Rectified Flow) to master text-to-image synthesis and improve sampling speed. It represents a large-scale effort to broaden the model’s capabilities. In contrast, SiT focuses on refining the unimodal DiT framework, optimizing the learning objective and sampling to enhance the core generative performance. They represent two branches of progress: one expanding functionality, the other perfecting the core engine.

Most recently, REPA and REPA-E introduce a paradigm-shifting approach that is orthogonal to architectural reinvention. Instead of redesigning the model, these methods focus on the training process itself. By aligning the model’s internal visual representations with those of powerful, pre-trained vision encoders, REPA surgically enhances the learning process. This simple regularization technique yields dramatic improvements in generation quality and convergence speed across different transformer-based models. It is not a new architecture, but a universal technique to make existing architectures learn better.

This distinction can be framed with an analogy: while works like SD3 and SiT are focused on building a better, more specialized hammer, REPA and REPA-E are akin to discovering a new, more effective way to swing any hammer. The former involves concrete design choices like loss functions and network modules, while the latter leverages a fundamental insight into the model’s nature—the critical link between representation and generation. This highlights the immense value of understanding the underlying principles of these models, as a single, well-placed “surgical” improvement can unlock performance gains that rival or even surpass years of architectural iteration.

7. Conclusion

The journey through the evolution of diffusion models, from the foundational work on U-Nets to the sophisticated transformer-based architectures of today, reveals a field in constant and rapid advancement. Our exploration of key milestones like Stable Diffusion, which democratized high-resolution synthesis by moving to a latent space, and Stable Diffusion 3, which introduced a multimodal, transformer-based architecture with rectified flow for faster sampling, highlights a clear trajectory toward more efficient, powerful, and versatile models.

A pivotal theme emerging from recent works like REPA and REPA-E is the profound impact of internal representation alignment. The discovery that enhancing a model’s visual understanding capabilities directly translates to superior generative quality marks a significant conceptual leap. Instead of solely focusing on architectural tweaks or novel loss functions, these methods “surgically” target the core of the model’s knowledge, yielding substantial improvements in performance and convergence speed with minimal changes. This underscores a deeper understanding of the “black box,” suggesting that the future of generative modeling may lie as much in interpretation and alignment as in architectural innovation.

Looking ahead, the landscape of generative AI is poised for even more transformative changes. Research presented in 2025 already points towards several exciting frontiers. The principles of representation alignment are being extended beyond images to other modalities like audio and video, promising synchronized, high-fidelity multimodal experiences. Innovations in native-resolution synthesis are breaking the long-standing constraints of fixed-size outputs, allowing single models to generate content at arbitrary scales and aspect ratios. Furthermore, new techniques are providing unprecedented levels of control, enabling users to personalize models, dictate precise layouts, and guide generation with a finesse that was previously unattainable.

As these technologies mature, the focus will undoubtedly expand from pure generation quality to practical usability, safety, and ethical deployment. The challenge will be to build models that are not only powerful but also controllable, interpretable, and aligned with human values. The continued synergy between open-source contributions and industrial research, exemplified by models like Stable Diffusion and the open publication of works like REPA-E, will be crucial in navigating this complex and exciting future. The techniques discussed in this report, from latent space diffusion to representation alignment, are not just incremental improvements; they are foundational steps toward a new era of intelligent, collaborative, and truly creative AI.

8. References

[1] “Veo 3 Model Card,” 2025. Accessed: Jun. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://storage.googleapis.com/deepmind-media/Model-Cards/Veo-3-Model-Card.pdf

[2] J. Ho, A. Jain, and P. Abbeel, “Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.11239, Jun. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.11239

[3] W. Peebles and S. Xie, “Scalable Diffusion Models with Transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.09748, Dec. 2022. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2212.09748

[4] N. Ma, M. Goldstein, M. S. Albergo, N. M. Boffi, E. Vanden-Eijnden, and S. Xie, “SiT: Exploring Flow and Diffusion-Based Generative Models with Scalable Interpolant Transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.08740, Jan. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2401.08740

[5] M. Heusel, H. Ramsauer, T. Unterthiner, B. Nessler, and S. Hochreiter, “GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.08500, Jun. 2017. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.08500

[6] X. Ding, Y. Wang, Z. Xu, W. J. Welch, and Z. J. Wang, “Continuous Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks: Novel Empirical Losses and Label Input Mechanisms,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2011.07466, Nov. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.07466

[7] T. Salimans, I. Goodfellow, W. Zaremba, V. Cheung, A. Radford, and X. Chen, “Improved Techniques for Training GANs,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2016, pp. 2234–2242.

[8] R. Rombach, A. Blattmann, D. Lorenz, P. Esser, and B. Ommer, “High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.10752, Dec. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2112.10752

[9] P. Esser, S. Kulal, A. Blattmann, R. Entezari, J. Müller, H. Saini, Y. Levi, D. Lorenz, A. Sauer, F. Boesel, D. Podell, T. Dockhorn, Z. English, K. Lacey, A. Goodwin, Y. Marek, and R. Rombach, “Scaling Rectified Flow Transformers for High-Resolution Image Synthesis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.03206, Mar. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.03206

[10] S. Yu, S. Kwak, H. Jang, J. Jeong, J. Huang, J. Shin, and S. Xie, “Representation Alignment for Generation: Training Diffusion Transformers Is Easier Than You Think,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.06940, Oct. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.06940

[11] W. Xiang, H. Yang, D. Huang, and Y. Wang, “Denoising Diffusion Autoencoders are Unified Self-supervised Learners,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.09769, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.09769

[12] X. Leng, J. Singh, Y. Hou, Z. Xing, S. Xie, and L. Zheng, “REPA-E: Unlocking VAE for End-to-End Tuning with Latent Diffusion Transformers,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10483, Apr. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.10483