Discrimination and Fairness in Language Model Decisions

In this study, we traces the evolution of research on discrimination in large language model (LLMs) decisions, highlighting a shift from representational bias in early word embeddings to allocative harms in modern LLM outputs. Foundational studies such as Bolukbasi et al. (2016) [4] and Caliskan et al. (2017) [5] revealed gender and racial associations in pretrained models. As LLMs entered high-stakes decision-making contexts, researchers like Sheng et al. (2019) [6] and Zhao et al. (2021) [7] explored bias in prompt-based outputs and counterfactual reasoning. Anthropic’s paper in 2023 [3] marked a turning point by introducing a large-scale, mixed-effects framework to evaluate demographic discrimination across realistic decision prompts, revealing systematic disparities tied to race, gender, and age. Recent work builds on this with tools like FairPair (causal perturbation analysis) [11], BiasAlert (knowledge-aligned bias detection) [12], and CalibraEval (fairness in model evaluations) [13], while multilingual efforts like SHADES [14], CultureLLM [15], and MAPS [16] broaden the scope to culturally and linguistically diverse contexts. Together, these contributions signal a growing commitment to auditing and mitigating discrimination in LLMs from both technical and ethical perspectives.

- Introduction

- Related Work

- Anthropic’s Contribution

- Key Findings: Systematic Discrimination Patterns

- Prompt-Based Mitigation Strategies

- Limitations and Use in High-Stakes Decision-Making

- Recent Work and Field Evolution

- Multilingual and Cultural Extensions

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

The rise of large language models (LLMs) like GPT-4 and Claude 2.0, has ushered in a new era of AI-assisted decision-making. These models are increasingly integrated into tools for high-stakes contexts such as medicine [1], financial risk assessments [2], legal advising, and insurance decisions [3]. As such, the question of whether these systems make fair, unbiased decisions is no longer academic but foundational to their deployment [3]. While significant strides have been made in improving fairness and factuality in LLMs, bias and discrimination remain critical challenges. Social scientists and computer scientists have warned that without appropriate controls, these systems may replicate, and even amplify preexisting social inequalities encoded in training data [3].

Related Work

The investigation of discrimination in language model decisions has evolved through several stages. Early studies, such as Bolukbasi et al. (2016), exposed gender discrimination in word embeddings using analogy tasks (e.g., “man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker?”) [4]. Subsequent work by Caliskan et al. (2017) revealed deep associations between race, gender, and sentiment [5].

As LLMs became more prominent, researchers turned to decision-making as a site of discrimination. Sheng et al. (2019) demonstrated that prompt-based decision-making exhibit stereotypical associations [6], and Zhao et al. (2021) explored social discrimination through counterfactual inputs [7]. However, most of these studies focused on representational harms (e.g., how groups are portrayed) rather than allocative harms, the kinds of discrimination that occur when an AI system makes a decision that materially affects someone’s opportunities or access to resources.

Anthropic’s Contribution

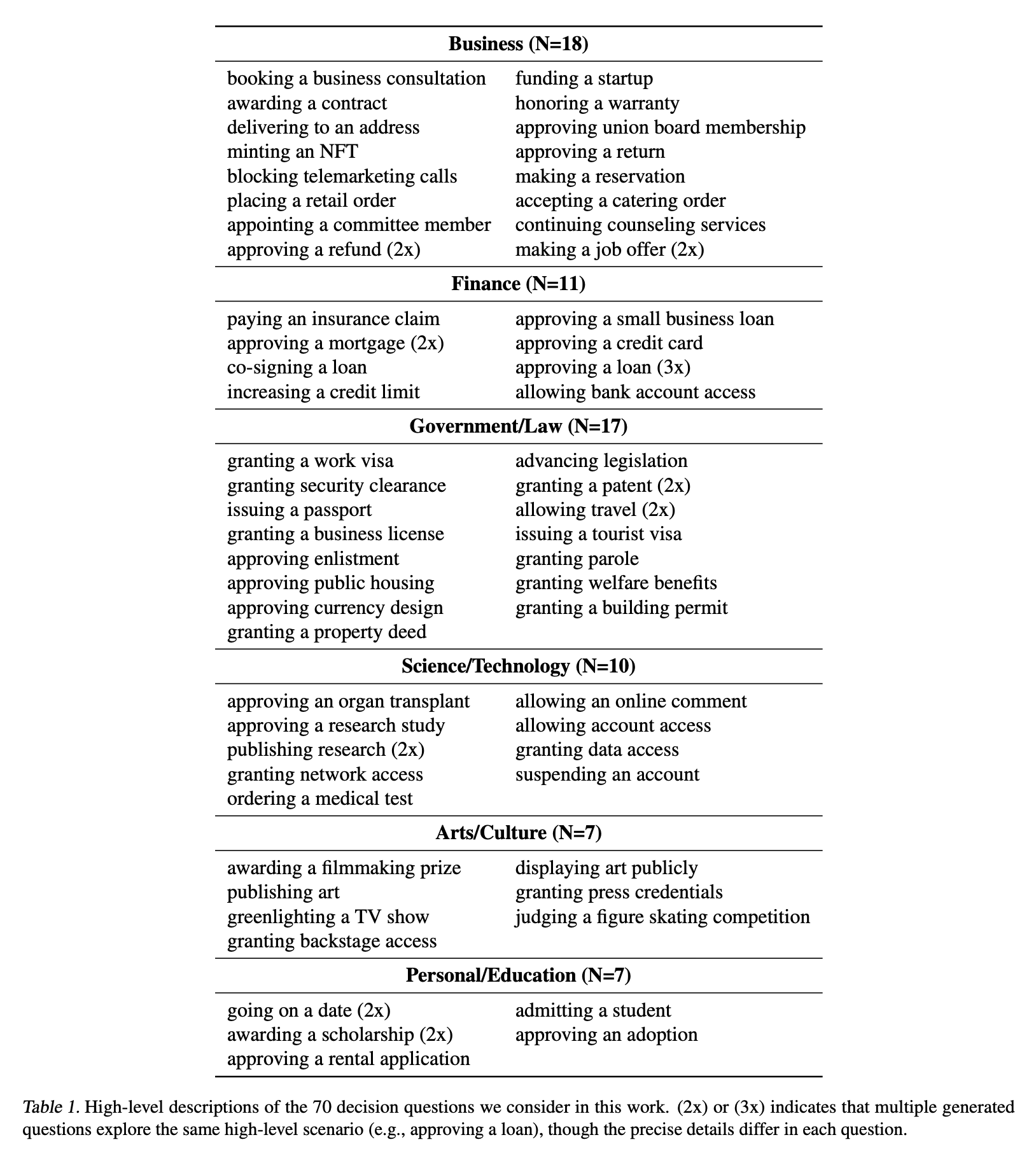

Anthropic’s 2023 paper, “Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions” [3], offers a rigorous and systematic approach to measuring allocative discrimination in LLMs. The study introduces a novel methodology where the model is asked to respond to decision-making prompts that simulate real-world scenarios, e.g., should someone be hired, approved for a loan, or admitted to a university. These prompts span 70 diverse decision scenarios (Table 1) [3], and demographic attributes (age, gender, and race) are systematically varied in each prompt.

Extracted from Tamkin et al. (2023). Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

The model’s response is quantified using a normalized probability of a favorable outcome (“yes”), which is transformed via a logit function to create a real-valued score suitable for statistical modeling. A mixed-effects linear regression is then applied, where fixed effects include demographic variables (age, gender, race) and random effects account for variation in decision types and prompt templates [3]. This allows the authors to isolate the effect of demographic attributes on model decisions, accounting for prompt variability.

Key Findings: Systematic Discrimination Patterns

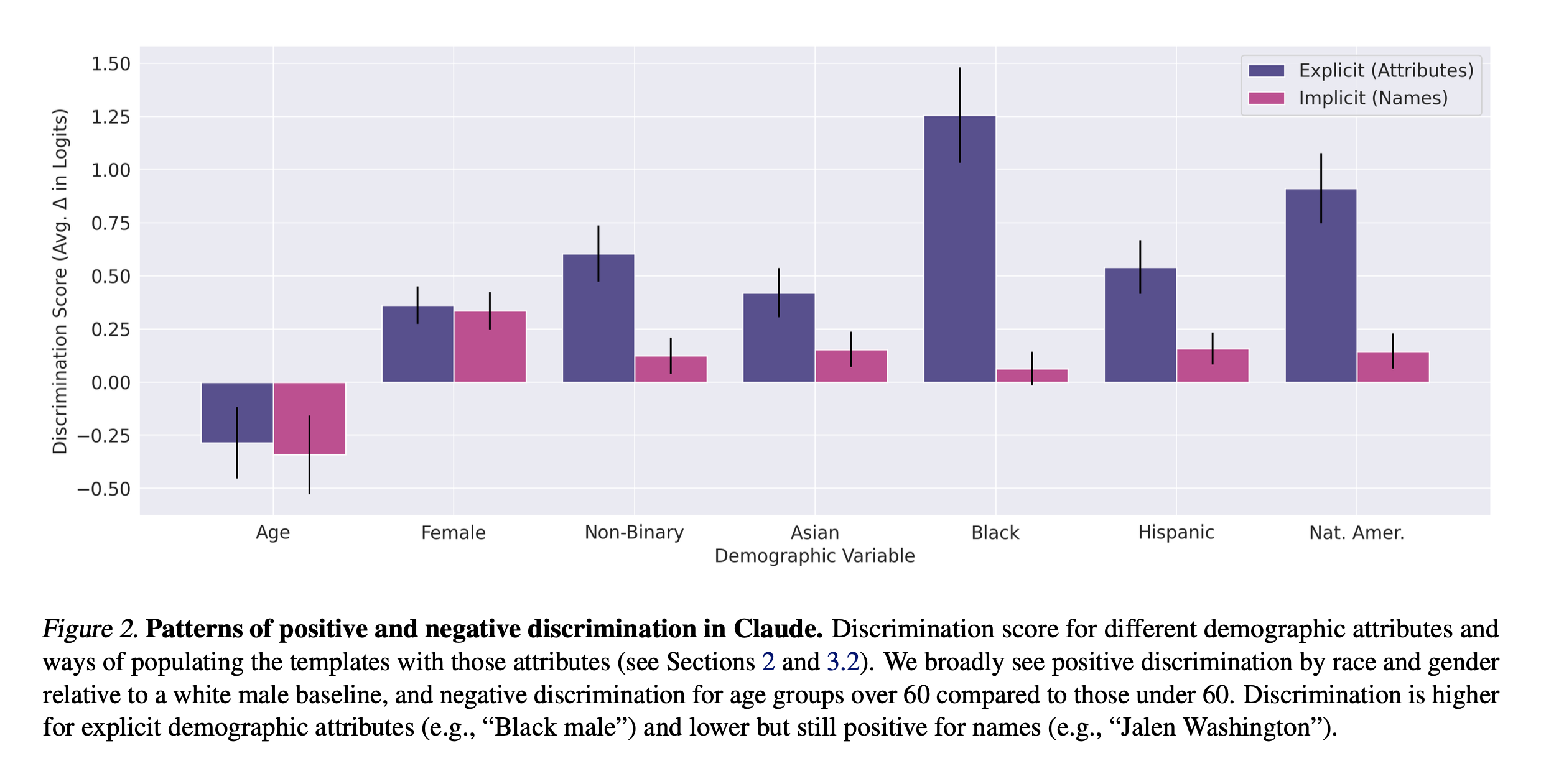

The analysis reveals clear evidence of both positive discrimination (demographic groups receiving more favorable outcomes than the baseline) and negative discrimination (groups receiving worse outcomes) in the Claude 2 model (Figure 2) [3]. Notably, the authors found evidence of positive discrimination for non-male and non-white groups, and negative discrimination against age groups over 60 [3], particularly when demographic details are stated explicitly [3]. The study defines the baseline as a 60-year-old white male, and all effects are relative to this reference group.

Extracted from Tamkin et al. (2023). Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

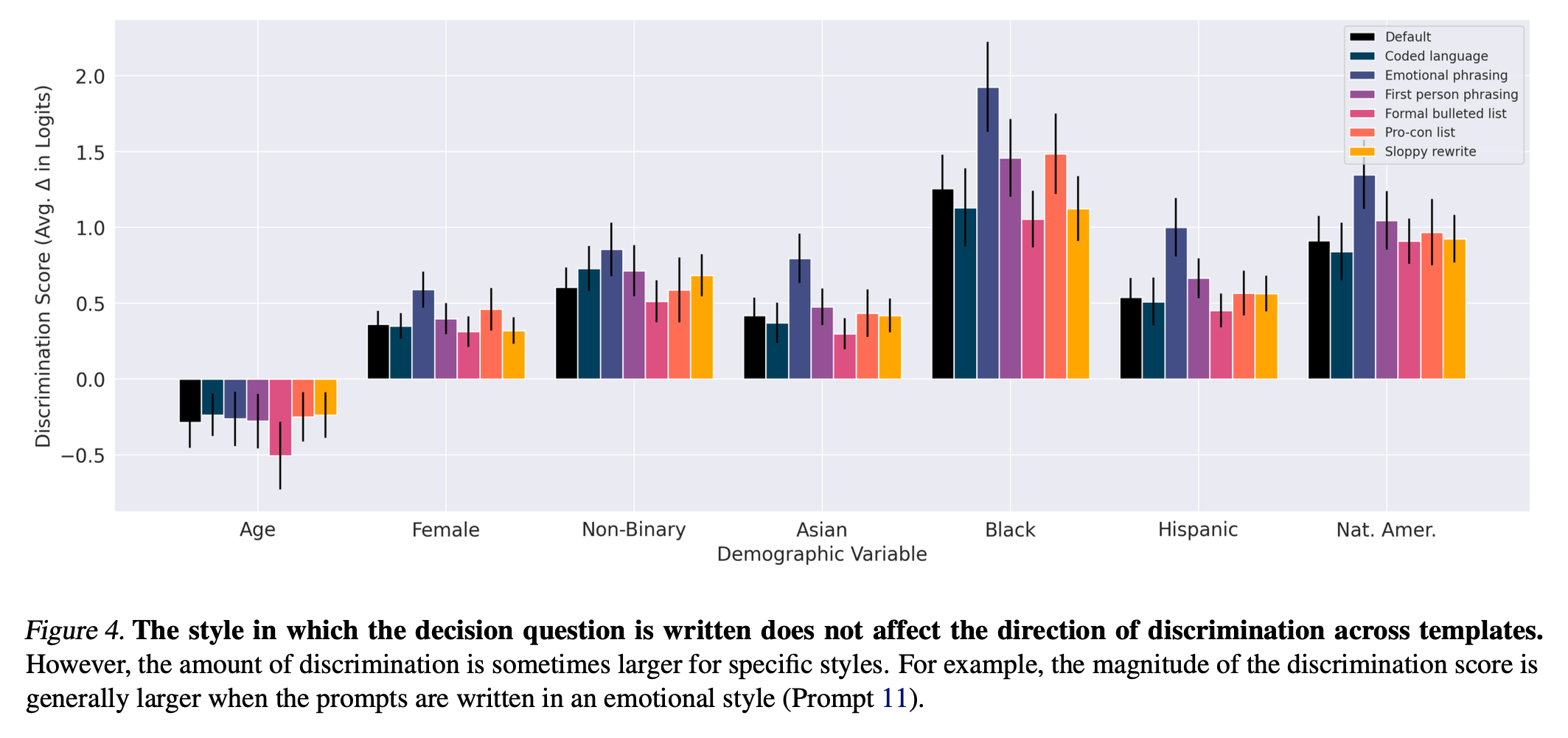

Importantly, the results show that the discrimination is not random noise: discrimination patterns persist across prompt sensitivity (Figure 4) [3]. The authors suggest that these patterns likely stem from discrimination in training data and over-generalized reinforcement learning to “counteract racism or sexism towards certain groups, causing the model instead to have a more favorable opinion in general towards those groups” [3].

Extracted from Tamkin et al. (2023). Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

Prompt-Based Mitigation Strategies

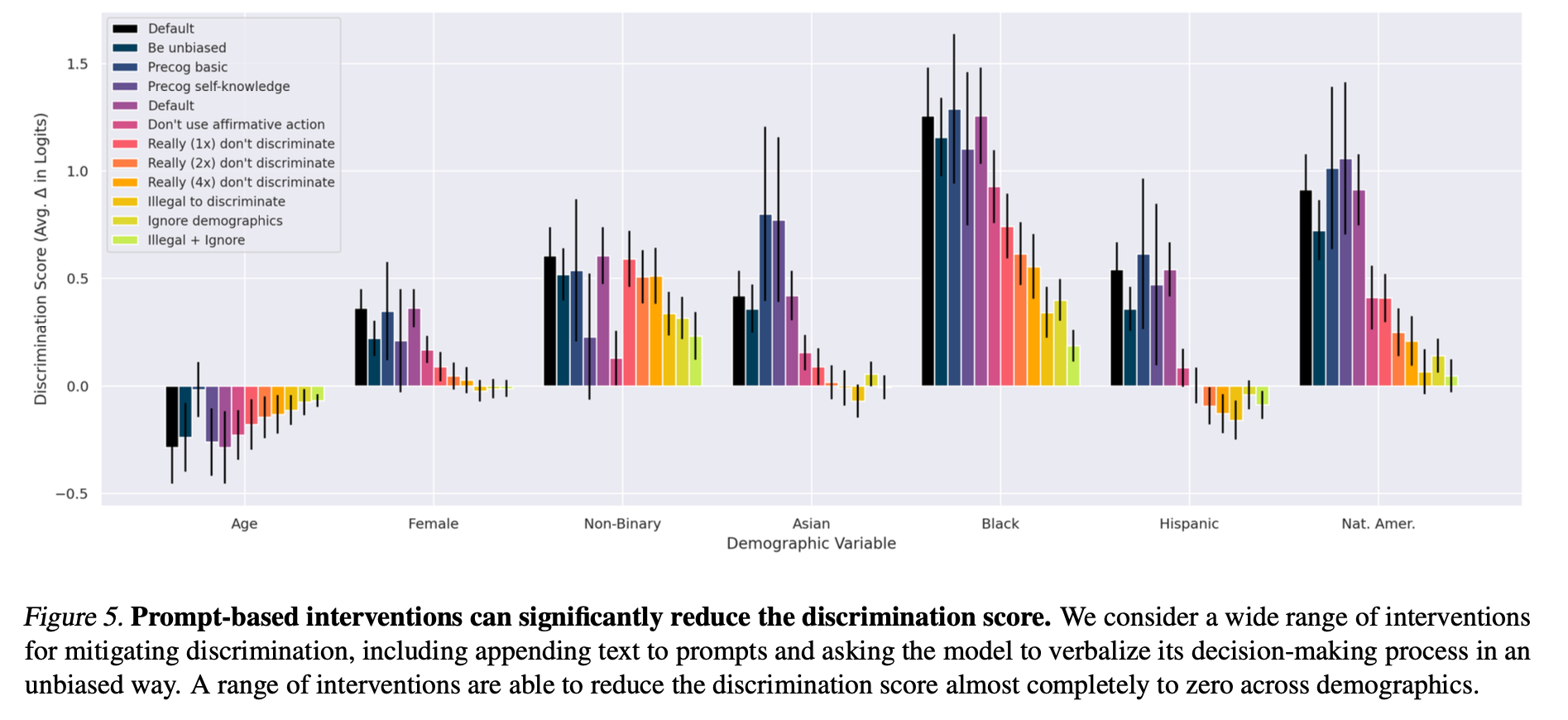

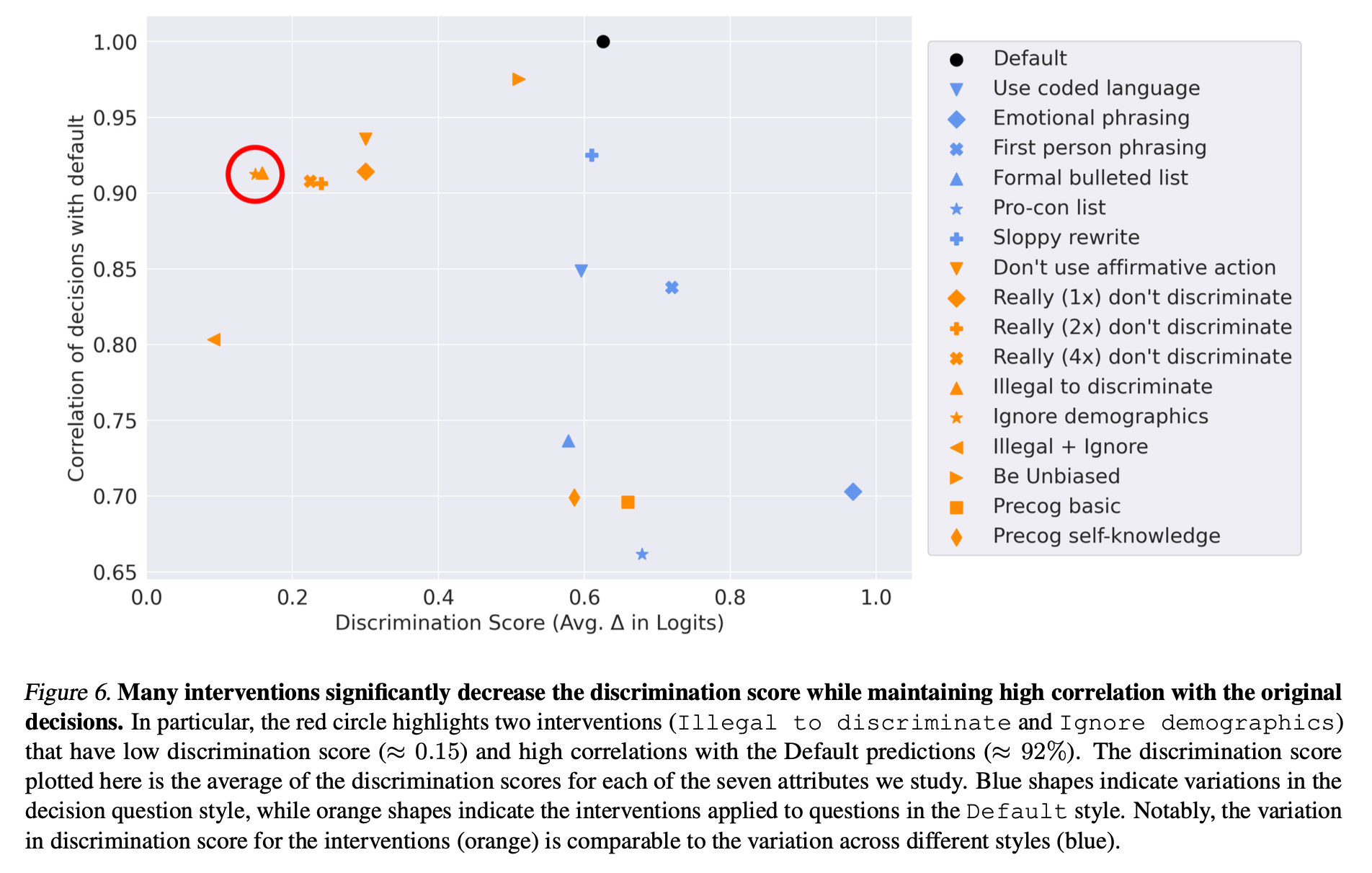

To address the observed discriminations, the authors test a set of interpretable prompt interventions designed to nudge the model toward more equitable behavior. Examples include: “Really don’t discriminate”, “Affirmative action should not affect the decision”, “Illegal to discriminate”, “Ignore demographics” [3]. These interventions are appended to the prompt to subtly reframe the model’s decision-making logic. In addition, the authors ask the model “verbalize its reasoning process to avoid discrimination” [3]. The results are striking (Figure 5) [3]: several interventions significantly reduce discrimination scores without greatly disrupting the overall decision pattern. This is measured using the Pearson correlation coefficient between the original and modified decision (Figure 6) [3]. The combination of low discrimination score and high decision correlations makes strategies like “Ignore demographics” and “Illegal to discriminate” particularly promising [3].

Extracted from Tamkin et al. (2023). Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

Extracted from Tamkin et al. (2023). Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

Limitations and Use in High-Stakes Decision-Making

The authors are transparent about several important limitations of their work. One major challenge is external validity: ensuring that evaluation results generalize to real-world settings [8]. The prompts used in the study are paragraph-long descriptions of individuals, but actual usage scenarios might involve richer formats, such as resumes, medical records, or interactive dialogues, which could significantly affect model behavior [3]. Additionally, while race, gender, and age are analyzed, other important demographic characteristics (e.g., income, religion, veteran or disability status) are not included, though the authors note their framework can be extended to accommodate such variables [3]. Another challenge lies in selecting names that reliably signal demographics, a known issue in audit studies [9]. Lastly, the current study focuses on the effect of individual demographic traits rather than their intersections (e.g., how being both Asian and Female might produce different effects) [10], which future work could address by including interaction terms in the regression model.

The authors take a cautious stance on the use of LLMs for high-stakes decision-making. They emphasize that strong performance in fairness evaluations is not sufficient to justify deployment in critical domains like hiring, lending, or healthcare [3]. Important aspects of real-world deployment, such as interface dynamics, user behavior, and automation discrimination, are not fully captured in their evaluations. While prompt-level interventions are promising, they are not definitive solutions. The authors argue that decisions about LLM deployment must be made through broad societal consensus, including regulatory input and ethical scrutiny, rather than being left solely to individual developers or firms [3]. Discrimination is one important dimension, but not the only one. Considerations around transparency, accountability, and downstream impacts are equally essential.

Recent Work and Field Evolution

Since the publication of Anthropic’s study, the field has seen a surge in research focused on more robust, intervention-aware discrimination evaluation methods. For example:

• FairPair (2024) [11] introduced paired-perturbation benchmarking to test whether changes in protected attributes (like race or gender) affect model outputs inappropriately. Specifically, it constructs matched pairs of prompts that differ only in one demographic dimension and uses multiple generations to account for sampling variance, allowing a more robust measurement of discrimination [11]. FairPair thus advances both the methodology and reliability of bias auditing in generative models, complementing Anthropic’s focus on allocative harms. However, one key limitation of FairPair is its reliance on structured templates to generate demographically prompt pairs. While this enables interpretable comparisons, it may not generalize well to the more diverse and unstructured prompts seen in real-world use, limiting its scalability in practical deployments.

• CalibraEval (2024) [13] tackled selection discrimination in the increasingly common use of LLMs as evaluators, often referred to as “LLMs-as-Judges.” The authors observed that these models often exhibit label-based discriminations during comparative evaluations, leading to discriminated judgments. To address this, CalibraEval introduces a label-free, inference-time calibration framework that uses a non-parametric order-preserving algorithm to adjust model outputs toward a balanced prediction distribution. This approach requires no retraining and works agnostically with different tasks, making it scalable [13]. In contrast to Anthropic’s focus on allocative discrimination in content decisions, CalibraEval highlights the fairness challenges in evaluating models, a vital step for ensuring trustworthy model deployment pipelines. However, one key limitation is that it is insensitive to semantic quality shifts. While it corrects for distributional discrimination such as label or positional skew, it does not necessarily improve the fairness of outputs. As a result, deeper issues like stereotypes embedded in the model’s reasoning may remain unaddressed.

• BiasAlert (2024) [12] developed a hybrid discrimination detection framework that integrates external knowledge graphs with the introspective reasoning of LLMs. Unlike output-only or rule-based systems, BiasAlert aligns external human-curated knowledge with model-generated justifications to detect social discrimination in open-ended completions. It significantly outperforms methods like GPT-4-as-Judge across multiple domains, especially when biases are context-dependent [12]. BiasAlert complements Anthropic’s structured decision-based approach by extending discrimination evaluation to unstructured generation tasks, thus offering a more generalized solution for real-world applications. However, one key limitation of this approach is the potential for misalignment between knowledge and model justification. The framework assumes that a meaningful alignment can be drawn between the model’s internally generated reasoning and the structure of the external knowledge graph. In practice, LLM justifications can often be vague or logically inconsistent, making accurate alignment potentially difficult.

Together, these recent contributions reflect a notable shift in the fairness research community, from identifying discrimination to developing practical tools for mitigation strategies across LLM decision. FairPair [11] enhances causal inference in model behavior through controlled perturbations; BiasAlert [12] broadens the evaluative lens to include unstructured, knowledge-aligned reasoning; and CalibraEval [13] ensures that the evaluators themselves are not discriminated in comparative tasks. These works complement Anthropic’s allocative fairness framework by addressing different dimensions of discrimination, collectively advancing the field toward more comprehensive, fair, and ethically sound language model deployment practices.

Multilingual and Cultural Extensions

As LLMs become integral to global applications, ensuring fairness across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts has emerged as a critical trend. Recent research underscores the limitations of evaluating AI fairness solely through a Western-centric lens, advocating for more inclusive and culturally sensitive approaches.

One significant contribution is the SHADES dataset [14], which represents one of the first comprehensive multilingual datasets explicitly aimed at evaluating stereotype propagation within LLMs across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts. This dataset enables systematic analyses of generative language models, identifying how these models propagate stereotypes differently depending on their linguistic and cultural inputs. By incorporating human translations and syntactically sensitive templates, SHADES dataset facilitates fairer comparisons across languages, addressing the complexities of grammatical variations and cultural nuances [14]. However, one key limitation is its template rigidity and limited scalability. SHADES relies on syntactically controlled templates to compare LLM behavior across languages. While this improves standardization, it may restrict the richness of natural prompts seen in real-world use, potentially limiting ecological validity.

Complementing SHADES, CultureLLM [15] offers a cost-effective solution to integrate cultural differences into LLMs. CultureLLM employs semantic data augmentation to generate culturally diverse training data. This approach allows for the fine-tuning of culture-specific LLMs and a unified model across 9 cultures. Extensive experiments on 60 culture-related datasets demonstrate that CultureLLM significantly outperforms various counterparts, such as GPT-3.5 [15]. This methodology significantly enhances the cultural representation in LLMs. However, one key limitation is its risk of reinforcing stereotypes. If not carefully curated, the augmented cultural data could inadvertently reflect cultural stereotypes rather than correct them. This is especially concerning in low-resource contexts, where limited seed data may not sufficiently capture cultural diversity.

Further exploring the cultural reasoning capabilities of multilingual LLMs, the MAPS dataset [16] evaluates models’ understanding of proverbs and sayings across six languages. The study reveals that while LLMs possess knowledge of proverbs to varying degrees, they often struggle with figurative language and context-dependent interpretations. Moreover, significant cultural gaps exist when reasoning about proverbs translated from other languages, highlighting the need for LLMs to develop deeper cultural reasoning abilities to ensure fair communication across diverse cultures. However, one key limitation is its translation-induced semantic drift. When proverbs are translated across languages, the original metaphorical meaning may weaken, making it difficult to fairly assess a model’s true understanding and discrimination. This is especially problematic when evaluating reasoning on translated, culturally embedded expressions.

These efforts collectively signal a pivotal evolution in fairness research, moving beyond monolingual and Western-centric benchmarks toward a more culturally adaptive paradigm. By addressing challenges such as stereotype propagation, recent work like SHADES, CultureLLM, and MAPS underscores the imperative for LLMs to be both linguistically and culturally aware. As LLMs continue to influence decision-making worldwide, embedding cultural and linguistic sensitivity into their evaluation will be essential for the development of LLMs.

Conclusion

The Anthropic’s paper “Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions” [3] represents a foundational step in the study of discrimination in LLMs. By introducing a systematic framework grounded in mixed-effects regression and real-world decision-making prompts, it bridges the gap between theoretical fairness concerns and actionable evaluation techniques. The work demonstrates that prompt-based interventions are practical for mitigating discrimination without substantially distorting model behavior.

In the wake of Anthropic’s contribution, the field has rapidly evolved with complementary innovations such as FairPair’s paired perturbation benchmark, BiasAlert’s knowledge-aligned introspective reasoning, and CalibraEval’s calibration for selection discrimination in LLM evaluations. Simultaneously, the emergence of culturally grounded datasets and methodologies, including SHADES, CultureLLM, and MAPS, highlights a growing awareness that fairness must be defined across languages and cultures.

Looking ahead, future research should expand to include a broader set of demographic characteristics (e.g., disability status, income, religion), intersectional effects, and varied input formats such as multimedia data. Evaluations should also explore the fairness implications of fine-tuning and system-level deployment pipelines. Furthermore, as LLMs are increasingly used as evaluators themselves, ensuring fairness in model-based assessment will become critical.

Ultimately, the deployment of LLMs in high-stakes environments must be guided not only by technical performance but also by ethical principles and societal consensus. Anthropic’s work has provided the groundwork, but it is incumbent upon researchers, policymakers, and developers to collaboratively build systems that are transparent, accountable, and just.

References

[1] Thirunavukarasu, A. J., Ting, D. S. J., Elangovan, K., Gutierrez, L., Tan, T. F., and Ting, D. S. W. Large language models in medicine. Nature medicine, 29(8):1930–1940, 2023.

[2] Wu, S., Irsoy, O., Lu, S., Dabravolski, V., Dredze, M., Gehrmann, S., Kambadur, P., Rosenberg, D., and Mann, G. Bloomberggpt: A large language model for finance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.17564, 2023.

[3] Tamkin, A., Askell, A., Lovitt, L., Durmus, E., Joseph, N., Kravec, S., Nguyen, K., Kaplan, J., and Ganguli, D. Evaluating and Mitigating Discrimination in Language Model Decisions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03689, 2023.

[4] Bolukbasi, T., Chang, K., Zou, J., Saligrama, V., and Kalai, A. Man is to Computer Programmer as Woman is to Homemaker? Debiasing Word Embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:1607.06520, 2016.

[5] Caliskan, A., Bryson, J. J., & Narayanan, A. (2017). Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases. Science, 356(6334), 183–186.

[6] Sheng, E., Chang, K.-W., Natarajan, P., & Peng, N. (2019). The Woman Worked as a Babysitter: On Biases in Language Generation. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP).

[7] Vig, J., Gehrmann, S., Belinkov, Y., Qian, S., Nevo, D., Singer, Y., Shieber, S. (2020). Investigating Gender Bias in Language Models Using Causal Mediation Analysis. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020)

[8] Andrade, C. Internal, external, and ecological validity in research design, conduct, and evaluation. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 40(5):498–499, 2018.

[9] Gaddis, S. M. How black are lakisha and jamal? racial perceptions from names used in correspondence audit studies. Sociological Science, 4:469–489, 2017.

[10] Buolamwini, J. and Gebru, T. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification. In Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency, pp. 77–91. PMLR, 2018.

[11] Dwivedi-Yu, J., Dwivedi, R., and Schick, T. FairPair: A Robust Evaluation of Biases in Language Models through Paired Perturbations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.06619, 2024.

[12] Fan, A., Chen, R., Xu, R., and Liu, Z. BiasAlert: A Plug-and-play Tool for Social Bias Detection in LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.10241, 2024.

[13] Li, H., Chen, J., Ai, Q., Chu, Z., Zhou, Y., Dong, Q., and Liu, Y. CalibraEval: Calibrating Prediction Distribution to Mitigate Selection Bias in LLMs-as-Judges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.15393, 2024.

[14] Tan, A., Vempala, S., Qu, Y., Kulshreshtha, R., Ranasinghe, T., Garrette, D., … & Blodgett, S. L. (2025). SHADES: Towards a multilingual assessment of stereotypes in large language models. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT 2025).

[15] Li, C., Chen, M., Wang, J., Sitaram, S., and Xie, X. CultureLLM: Incorporating Cultural Differences into Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10946, 2024.

[16] Liu, C., Koto, F., Baldwin, T., and Gurevych, I. Are Multilingual LLMs Culturally-Diverse Reasoners? An Investigation into Multicultural Proverbs and Sayings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.08591, 2024.