Recent Developments in GUI Web Agents

Web agents are a new class of agents that can interact with the web. They are able to navigate the web, search for information, and perform tasks. They are a type of multi-modal agent that can use text, images, and other modalities to interact with the web. Since 2024, we have seen a surge in the development of web agents, with many new agents being developed and released. In this blog post, we survey the recent developments in the field of web and particularly GUI agents, and provide a comprehensive overview of the state of the art. We review core benchmarks - WebArena, VisualWebArena, Mind2Web, and AssistantBench — that have enabled systematic measurement of these capabilities. We discuss the backbone vision-language models that power these agents, as well as the recent advancement in reasoning.

- Introduction

- Background: From Text-Based to Multi-modal Web Agents

- Core Benchmarks

- Backbone Vision-Language Models and UI Grounding

- Architectures and Methods: Enhancing Reasoning in GUI Agents

- [Extra Credit Attempt] Running the RealWebAssist Benchmark with Qwen-2.5-VL

- Conclusion

- References

Introduction

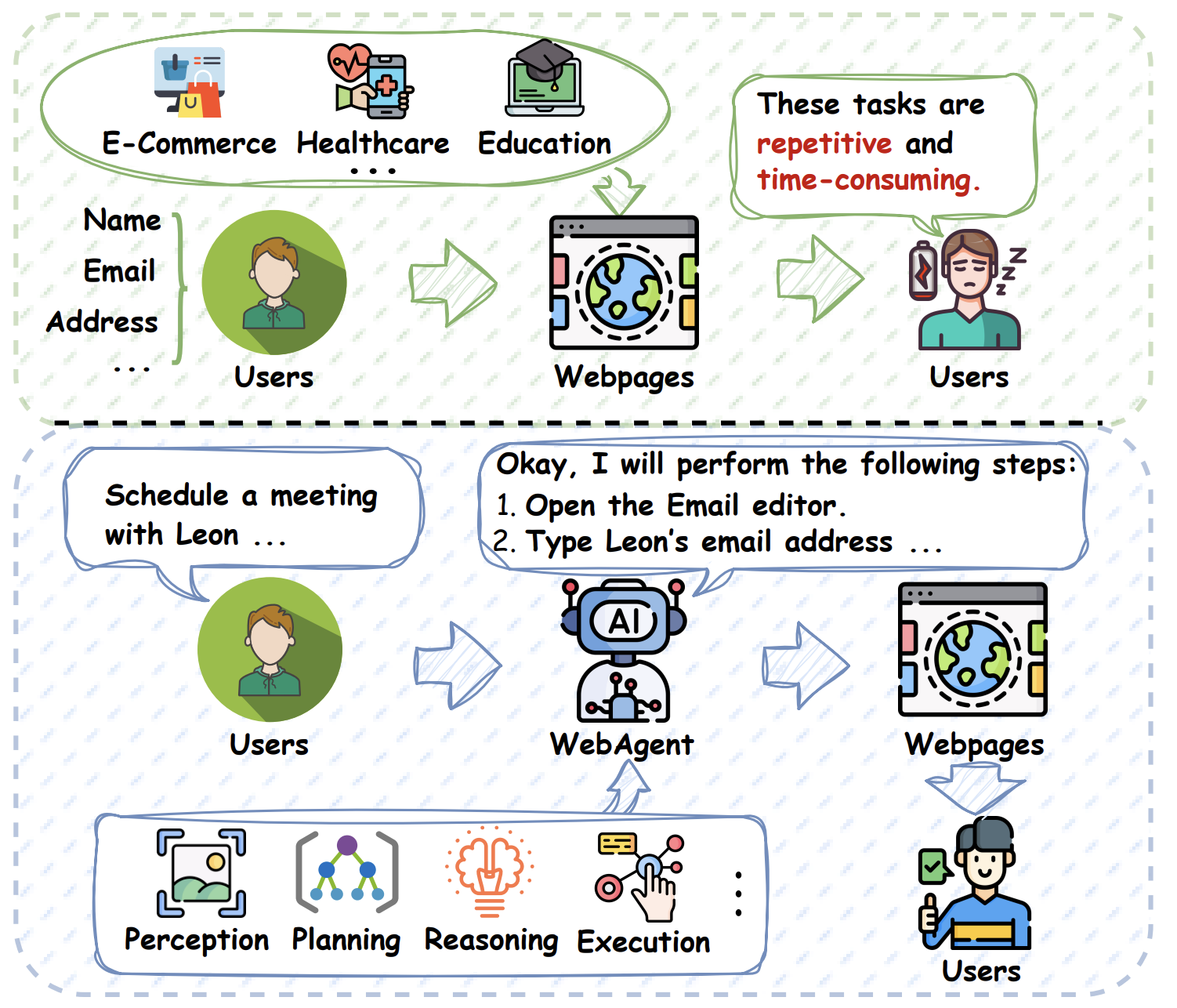

Graphical User Interface (GUI) web agents are autonomous agents that interact with websites much like a human user – by clicking, typing, and reading on web pages. In recent years, there has been rapid progress in developing general-purpose GUI web agents powered by large (multimodal) language models (LLMs). These agents aim to follow high-level instructions (e.g. “Find the cheapest red jacket on an online store and add it to the cart”) and execute various tasks across different websites.

Over the past two years, we have witnessed an extraordinary leap in the development of web agents: intelligent systems capable of navigating, perceiving, and interacting with websites on behalf of users. Moving beyond traditional API-based or text-only interfaces, a new wave of GUI (Graphical User Interface) web agents has emerged, powered by multimodal foundation models that can “see” and “act” in complex digital environments. These agents now demonstrate the potential to complete multi-step, visually grounded tasks across domains like e-commerce, travel booking, and social media management.

A key challenge driving current research is reasoning capability: GUI agents must plan multi-step actions, handle dynamic web content, hop between different web pages, and sometimes recover from mistakes or unexpected outcomes. Unlike their text-based predecessors, GUI agents must coordinate vision, language, and action to succeed in dynamic, high-variance web environments. They must plan ahead, adapt to evolving page structures, recover from failures, and make context-sensitive decisions in real time. As a result, recent advances have not only focused on expanding model capability, but also on enhancing reasoning paradigms—introducing reflection, branching, rollback, and deliberative planning as first-class citizens in agent design. In this post, we provide a comprehensive survey of recent progress in GUI web agents, with a particular emphasis on how reasoning has been incorporated into the latest architectures. We trace this evolution across key benchmarks, vision-language foundation models, UI grounding techniques, and learning paradigms—highlighting both the engineering innovations and scientific insights that have shaped the state of the art. Special attention is given to applications in e-commerce, where the demands of visual search, product comparison, and transactional planning make this a particularly challenging and instructive testbed for intelligent agents.

An illustration of basic web tasks and the pipeline of Web and GUI web agents. Given the user instruction, GUI web agents complete tasks by perceiving the environment, reasoning about the action sequences, and executing actions autonomously. Source: [32]

Background: From Text-Based to Multi-modal Web Agents

Early “web agents” were often text-based, interfacing with the web via textual inputs/outputs or APIs rather than through a visual GUI. For example, a text-based agent might read the HTML or use a browser’s accessibility layer to get page text, then choose an action like following a link or submitting a form by ID. Notable early systems included OpenAI’s WebGPT (2021) [1] for web question-answering and various reinforcement learning (RL) agents on simplified web environments. These text-based agents relied on parsing textual content and often used search engine APIs or DOM trees. Their reasoning largely resembled traditional NLP tasks – e.g. retrieving relevant information or doing reading comprehension – and they did not need to reason about layout or visual elements.

By contrast, GUI web agents operate on the actual rendered web interface (like a human using a browser). This introduces new challenges and differences in reasoning.

The first one is Perception and Grounding: GUI agents must interpret the visual layout and GUI elements. They may receive a DOM tree or a rendered screenshot of the page. For instance, a task might involve recognizing a “red BUY button” or an image of a product. Text-only models struggle with such visual cues. Thus, GUI agents often incorporate vision (to understand images, colors, iconography) in addition to text. Reasoning for GUI agents often means linking instructions to the correct GUI element or image – a form of grounded reasoning not present in purely text agents.

The second one is Action Space & Planning: A text-based agent’s actions can be abstract (e.g. “go to URL” or “click link by name”), whereas a GUI agent deals with low-level events (mouse clicks, typing) on specific coordinates or element IDs. This requires more procedural reasoning: the agent must plan a sequence of GUI operations to achieve the goal. Often the agent must navigate through multiple pages or UI states, which demands long-horizon planning. For example, buying a product involves searching, filtering results, clicking the item, adding to cart, and possibly checkout – multiple steps that must be reasoned about and executed in order. Modern GUI agents leverage LLMs’ ability to plan by breaking down goals into sub-goals, sometimes explicitly writing out multi-step plans [2]. In comparison, text-based agents typically handle shorter-horizon tasks (like finding a specific fact on Wikipedia) with simpler sequential reasoning.

The third one is Dynamic Interaction and Uncertainty: Web GUIs are dynamic – pages can change or have pop-ups, and incorrect actions can lead the agent astray. GUI agents need robust error recovery strategies. This has led to new reasoning techniques like reflection and rollback. For example, an agent might try an action, realize it led to an irrelevant page, and then go back and try an alternative – a capability highlighted as essential in recent work [3]. Text agents, while they also handle some dynamic choices (e.g. picking the next link to click), typically operate in a more static information space and have less need for such UI-specific recovery reasoning.

GUI web agents require visual understanding, sequential decision-making, and error-aware reasoning that goes beyond what text-based agents historically needed. These differences have encouraged new research directions to equip GUI agents with better reasoning skills. Before diving into those developments, we next overview the benchmarks and environments that have been created to train and evaluate modern GUI web agents.

Core Benchmarks

In recent years, several benchmarks and agent frameworks have been proposed to evaluate and advance autonomous agents that can interact with websites through a graphical user interface (GUI). These systems combine natural language understanding, web page vision/DOM parsing, and action execution (clicking, typing, etc.) to follow instructions on real or simulated websites. In this section, we review five notable recent projects – VisualWebArena, Mind2Web, Online-Mind2Web, WebVoyager, and RealWebAssist – focusing on their core ideas, evaluation methodologies (tasks, datasets, metrics), key results, and the strengths/limitations of each approach.

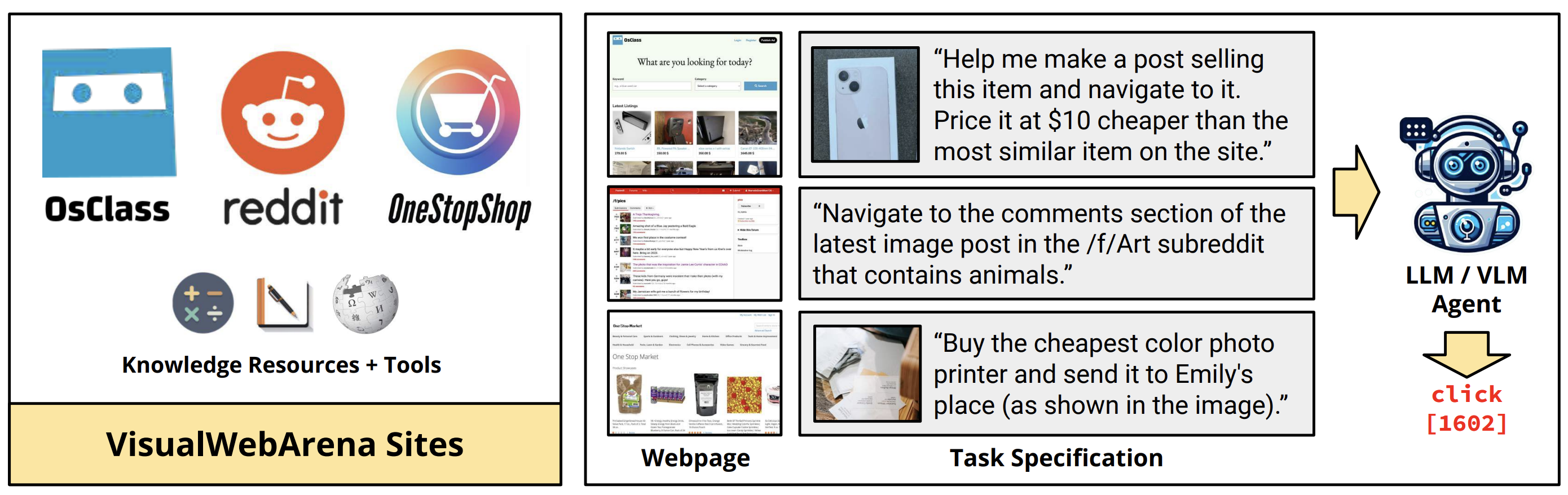

VisualWebArena

VisualWebArena (VWA) is a benchmark designed to test multimodal web agents on realistic tasks that require visual understanding of web content [4]. Prior web agent benchmarks mostly used text-only information, but VWA includes images and graphical elements as integral parts of the tasks. The goal is to evaluate an agent’s ability to process image-text inputs, interpret natural language instructions, and execute actions on websites to accomplish user-defined objectives. This benchmark builds on the WebArena framework (a realistic web environment) by introducing new tasks where visual content is crucial (e.g. identifying items by images or interpreting graphical page elements).

VWA comprises 910 diverse tasks in three web domains: an online Classifieds site (newly created with real-world data), an e-Shopping site, and a Reddit-style forum. Tasks range from purchasing specific products (which may require recognizing product images) to navigating forums with embedded media. Agents interact with webpages that are self-hosted for consistency. Success is measured by whether the agent achieves the correct end state on the website (functional task completion). Human performance on these tasks is about 88–89% success, indicating the tasks are feasible for people but non-trivial. An example task is: “Find a listing for a red convertible car on the classifieds site and report its price” – requires the agent to visually identify the car’s image/color on the page (beyond just text).

The benchmark supports various agent types. The authors evaluated state-of-the-art large language model (LLM) based agents, including text-only agents and vision-enabled agents (e.g. GPT-4 with vision, open-source vision-language models). Agents observe either a DOM-derived accessibility tree (textual interface) or the rendered webpage image (for vision models), sometimes augmented with image captions (generated by a tool like BLIP-2) for text models. Agents produce actions such as clicking UI elements or entering text. Some experiments also used a Set-of-Mark (SoM) [5] approach – a method to highlight possible interactive elements for the agent to consider – to aid decision making.

VisualWebArena is a benchmark suite of 910 realistic, visually grounded tasks on self-hosted web environments that involve web navigation and visual understanding Source: [4]

Key Results: Text-Only vs Multimodal: A GPT-4 based agent using only text (no vision) achieved under 10% success on VWA tasks (≈7% in one setting). In contrast, GPT-4V (Vision-enabled GPT-4) achieved roughly 15% overall success, more than doubling the success rate by leveraging page images. Even augmenting a text agent with image captions improved success to ~12.8%, but fell short of a true vision model. This underscores that visual context is often critical: purely text-based agents miss cues that are obvious to multimodal agents (e.g. recognizing a product from its photo). The evaluation showed text-only LLM agents often fail when tasks involve identifying visual attributes (colors, shapes, etc.) or non-textual cues. VisualWebArena is the first benchmark to focus on visually-grounded web tasks in a realistic setting. It provides a controlled environment with reproducible websites, enabling rigorous comparison of agents. It highlights the importance of vision in web agents: many real-world web tasks (shopping for an item of a certain style, recognizing icons/buttons, etc.) cannot be solved by text parsing alone.

Mind2Web

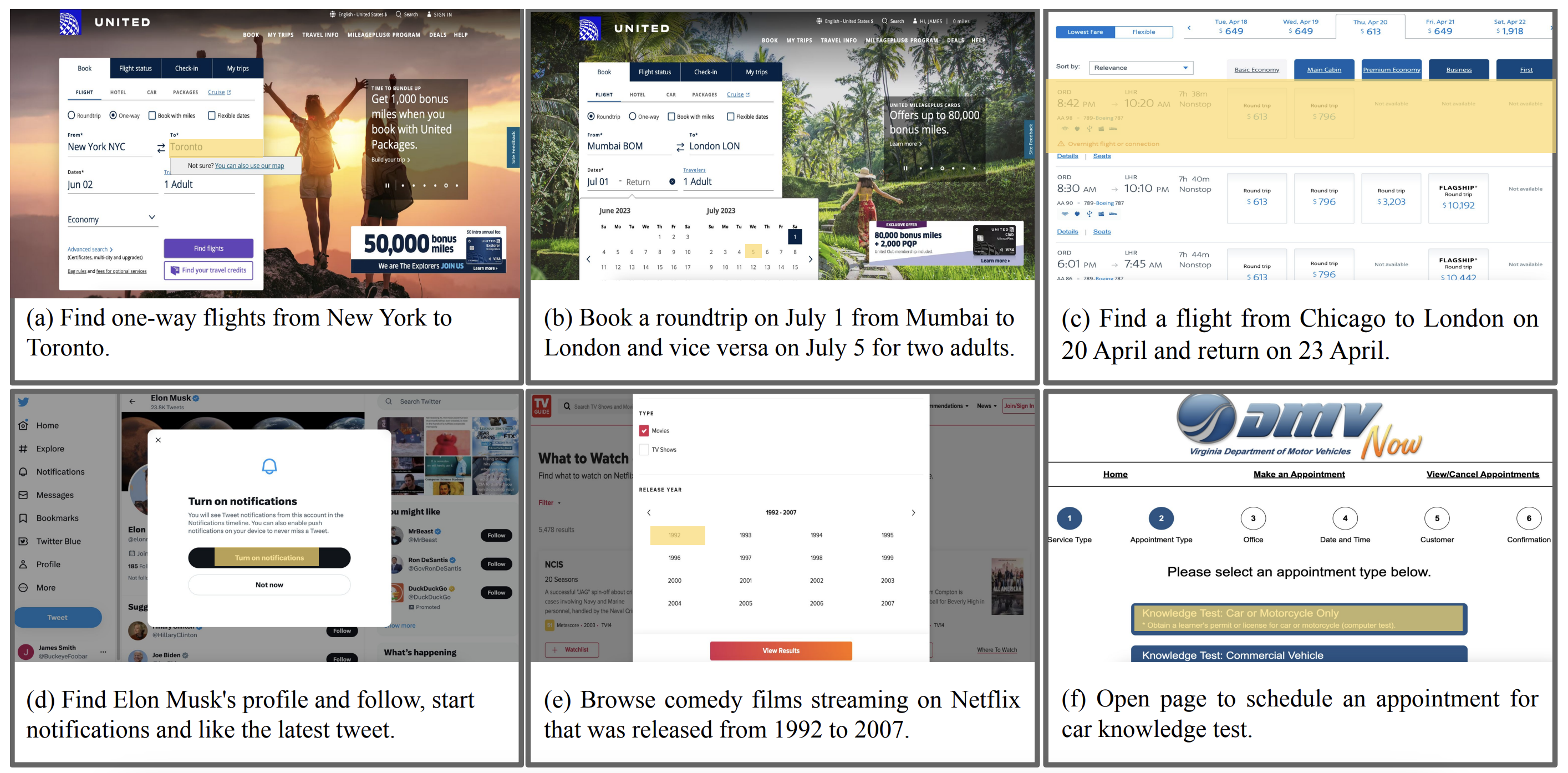

Mind2Web is introduced as the first large-scale dataset for developing and evaluating a “generalist” web agent – one that can follow natural language instructions to complete complex tasks on any website [6]. Prior benchmarks often used either simulated web pages or a limited set of websites/tasks, which risked overfitting. Mind2Web instead emphasizes breadth and diversity: it contains over 2,000 tasks collected from 137 real-world websites spanning 31 domains (e-commerce, social media, travel, etc.). Each task is open-ended (expressed in natural language) and comes with a human-crowdsourced action sequence demonstrating how to complete it, providing both a goal specification and a ground-truth solution path.

Sample tasks and domains featured in mind2web. Source: [6]

Online-Mind2Web

Online-Mind2Web is a follow-up benchmark that addresses a critical question: Are web agents as competent as some benchmarks suggest, or are we seeing an illusion of progress? [7] The authors of this study argue that previously reported results might be overly optimistic due to evaluation on static or simplified environments. Online-Mind2Web instead evaluates agents in a live web setting, where they must perform tasks on actual, up-to-date websites – thus exposing them to real-world variability and unpredictability. It consists of 300 diverse tasks spanning 136 popular websites, collected to approximate how real users would instruct an agent online. This includes tasks across domains like shopping, travel, social media, etc., similar in spirit to Mind2Web’s diversity but executed on the real web.

The authors developed an LLM-as-a-Judge system called WebJudge to automatically evaluate whether an agent succeeded in a given task, with minimal human labor. WebJudge uses an LLM to analyze the agent’s action history and the resulting web states (with key screenshots) to decide if the goal was achieved. This method achieved about 85% agreement with human evaluators on success judgments, substantially higher consistency than prior automatic metrics, substantially higher consistency than prior automatic metrics.

WebVoyager

WebVoyager [8] has a set of tasks that are open-ended user instructions that require multi-step interactions. For example, tasks might include “Book a hotel room in New York for next weekend on Booking.com” or “Find and compare the prices of two specific smartphones on an e-commerce site”. The tasks are meant to reflect practical web goals (searching, form-filling, navigating multi-page flows, etc.) and often require combining information gathering with action execution. Because evaluating success on such open tasks can be tricky, WebVoyager’s authors used an automatic evaluation protocol leveraging GPT-4V (similar in spirit to WebJudge). They had GPT-4V examine the agent’s outcome (e.g., final page or sequence of pages visited) and compare it to the intended goal, achieving about 85% agreement with human judgment of success.

Its benchmark and results validated that multimodal agents can substantially outperform text-only agents on real-world websites. Another strength is the introduction of an automatic evaluation metric with GPT-4V to reduce reliance on slow human evaluation

RealWebAssist

RealWebAssist [9] is a benchmark aimed at long-horizon, sequential web assistance with real users. Unlike one-shot tasks (e.g. “buy X from Amazon”), this benchmark considers scenarios where a user interacts with an AI assistant over an extended session comprising multiple interdependent instructions. The key idea is to simulate a personal web assistant that can handle an evolving to-do list or goal that unfolds through conversation. RealWebAssist addresses several real-world complexities not covered in prior benchmarks. It extends the challenge to interactive, personalized assistance, highlighting the significant gap between current AI capabilities and the full vision of a personal web assistant that can handle ambiguous, evolving user needs over long sessions.

For example, a user might start with “I need a gift for my mother’s birthday”, then later add “She likes gardening” – the agent must adjust its plan. The benchmark includes such evolving goals. The agent might need to learn or keep track of a particular user’s preferences/routines. E.g., “Order my usual Friday takeout” implies knowing what “usual” means for that user. Instructions come from real users (not annotators inventing them), so they reflect personal language quirks and context assumptions.

As with other GUI agents, the assistant must interface with actual web pages (click buttons, fill forms). RealWebAssist emphasizes aligning instructions with the correct GUI actions – e.g., if the user says “open the second result,” the agent must translate that to clicking the second item on the page.

The benchmark consists of sequential instruction episodes collected from real users. For evaluation, the authors consider the following evaluation metrics:

- Task success rate: Measures whether the web agent successfully executes all instructions in a given task sequence.

- Average progress: Calculates what percentage of instructions the agent completes correctly before making its first mistake in a task.

- Step success rate: Evaluates the agent’s performance in a controlled setting where it only needs to handle one instruction at a time, with all previous steps assumed to be completed successfully.

Backbone Vision-Language Models and UI Grounding

Multimodal LLMs have become the core enablers of GUI agents. Since 2024, a new generation of such models has been adapted to interact with digital interfaces using vision and language. Notably, closed-source giants like OpenAI’s GPT‑4 and Google’s Gemini [17] are pushing capability boundaries. OpenAI’s developed a Computer-Using Agent (CUA) to drive an autonomous GUI agent named Operator [18]. This system can visually perceive screens and perform mouse/keyboard actions without specialized APIs. Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 [19] has also gained a “Computer Use” capability, enabling it to “view” a virtual screen and emulate mouse/keyboard interactions. Meanwhile, the community has introduced strong open-source multimodal models to democratize GUI agents. Notably, Alibaba’s Qwen-2.5-VL [20] has delivered impressive visual understanding – e.g. it can handle very large image inputs and precise object localization. Similarly, the ChatGLM family has spawned AutoGLM [21], a specialized multimodal agent model. AutoGLM augments a ChatGLM-based LLM with vision and is trained via reinforcement learning for GUI tasks.

UI Grounding - Aligning Perception and Action

Achieving fluent GUI automation requires “grounding” the model in the actual UI – i.e. linking the model’s linguistic plans to on-screen elements and executable actions. Recent research has made substantial progress in perception, UI understanding, and action grounding for GUI agents.

Agents must convert a raw GUI (pixels or DOM data) into a form the model can reason about. Two common approaches emerged: (a) leveraging the model’s own multimodal abilities, and (b) inserting an intermediate perception module. The first approach is exemplified by GPT-4V and similar LMMs that directly take screenshots as input. For instance, SeeAct [22] simply feeds the webpage screenshot to GPT-4V and lets it describe and decide actions. The second approach uses computer vision techniques to explicitly identify UI components before involving the LLM. An example is the framework by Song et al. [23], which includes a YOLO-based detector to find UI elements (buttons, text fields, etc.) and read their text via OCR, prior to invoking GPT-4V for high-level planning. Similarly, AppAgent V2 [24] improved over a pure-LLM baseline by integrating OCR and object detection to recognize on-screen widgets, rather than relying on a brittle DOM parser. Microsoft’s UFO agent [25] uses a dual-agent design: one “vision” agent inspects the GUI visually, while another “control” agent queries the app’s UI hierarchy. Agent S [26] likewise feeds both the rendered pixels and the accessibility tree of desktop apps into its LLM module.

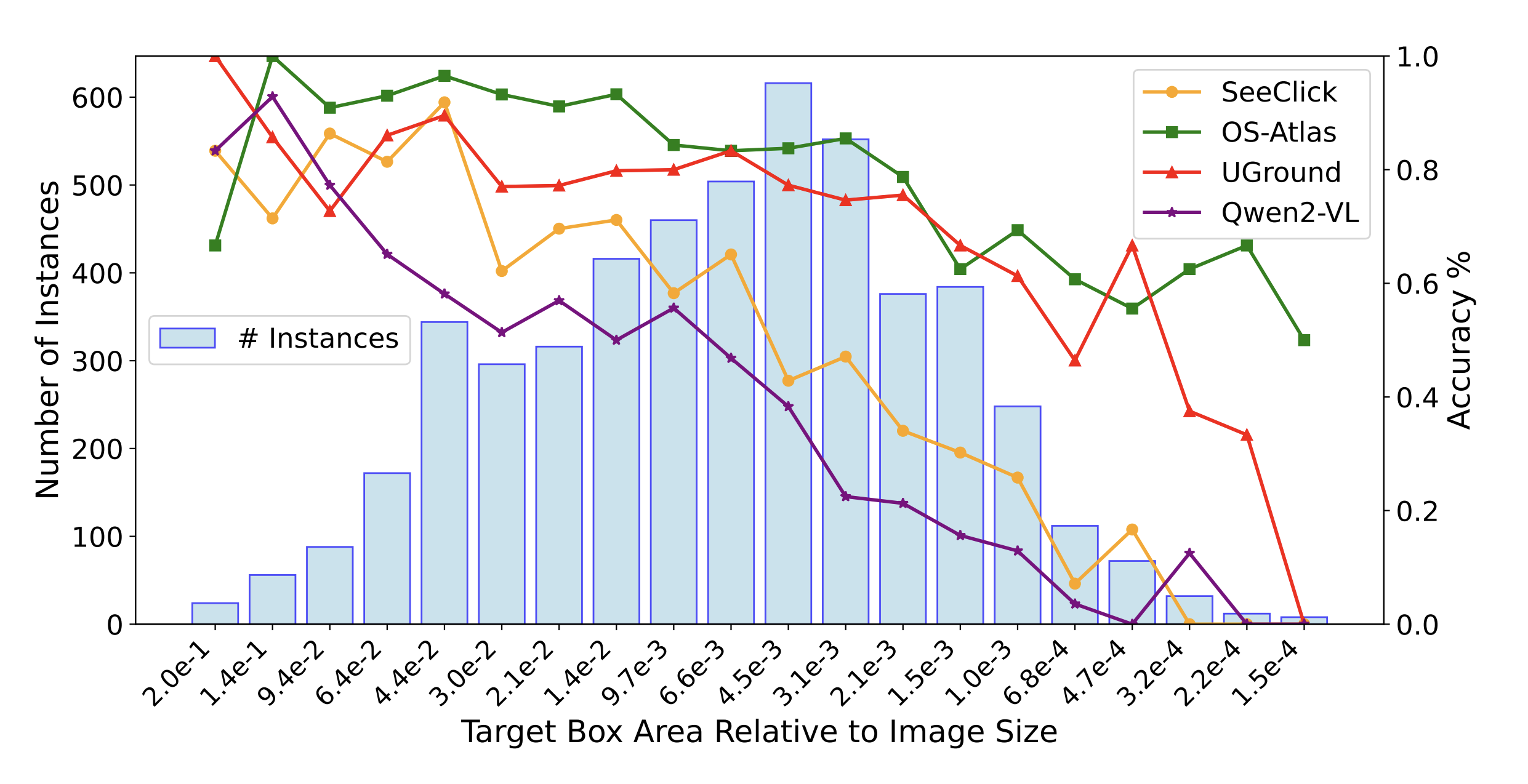

Performance of the expert GUI grounding models on the ScreenSpot-v2 GUI grounding benchmark. The elements on the x-axis are arranged in logarithmically decreasing order, representing their relative size in the entire image. There is a universal decrease in accuracy as the target bounding box size becomes smaller Source: [29]

After perception, a key challenge is mapping the model’s textual plan (e.g. “Click the OK button, then type the name”) to actual interface actions. SeeAct tested a set-of-candidates prompting strategy where GPT-4V would be asked to mark on the image which element to click. A more robust solution is to instrument the UI with tags or coordinates that the model can reference. Several web agents now render numeric labels next to clickable elements in the screenshot and supply the list of those elements (with their HTML attributes) to the LLM. The LLM’s output can then include the label of the intended element, making execution unambiguous. On mobile UIs, others have used XML UI trees and asked the LLM to match text in the tree; AppAgent V2’s use of detected text tokens is another form of aligning visual info with semantic targets.

Despite this progress, UI grounding remains a core challenge. The consensus in recent literature is that while today’s agents can handle simple cases, complex interfaces still pose problems.

Architectures and Methods: Enhancing Reasoning in GUI Agents

Developing a general-purpose GUI web agent requires innovation on multiple fronts: how the agent’s policy is represented (LLM-based, reinforcement learned, etc.), how it integrates vision and text, and how it plans and reasons about its next actions. Recent works have explored a spectrum of approaches:

Prompt-Based Planning and Chain-of-Thought

Large Language Models, especially since GPT-4 [10] and their open-source equivalents, have become the “brains” of many web agents. Given an instruction and the current page (as text or description of GUI), the LLM can be prompted to output an action (e.g. click(“Add to Cart”)). Early attempts simply used zero-shot or few-shot prompting with GPT-4, but these often lacked deep reasoning for multi-step tasks. To address this, researchers introduced chain-of-thought (CoT) strategies for web agents: the model is encouraged to generate a step-by-step rationale before choosing each action. This was inspired by the ReAct paradigm [11], which interleaves reasoning text (“I need to find a search bar on the page…”) with explicit actions. By reasoning explicitly, the LLM can plan several steps ahead or consider contingencies.

A recent development in 2025 is WebCoT [3], which identifies key reasoning skills for web agents and trains models to use them. WebCoT emphasizes reflection & lookahead, branching, and rollback as three crucial abilities. Instead of relying on an LLM to implicitly learn these, they reconstruct training trajectories with rich rationales that demonstrate, for example, branching (considering multiple possible paths) and rollback (recovering from a bad click) in the chain-of-thought. By fine-tuning an LLM on these augmented trajectories, WebCoT achieved notable gains on WebVoyager, and on tasks like Mind2Web-live and web search QA.

Similarly, other works have looked at incorporating planning abilities directly into the model’s action space. AgentOccam [2] by Amazon researchers is one such approach: it introduces special actions like branch and prune which allow the agent to explicitly create and manage a tree of sub-plans. For example, an e-commerce task might require information from two different pages; the agent can branch its plan into two parallel subgoals, gather results, then prune away completed branches. By simplifying the action space (removing distracting or seldom-used actions) and adding these planning operations, AgentOccam achieved a strong performance baseline on the WebArena benchmark.

Another notable result of incorporating better reasoning came from LASER (2024), which tackled WebShop tasks. LASER reframed the web task for the LLM as an explicit state-space exploration problem [12]. Instead of having the LLM treat every step as unrelated to the next, LASER defines distinct states (e.g. “search results page” or “product page”) and allowed actions from each state, enabling the model to backtrack and explore alternatives. This approach acknowledged that an LLM agent may make a mistake, but it can recover by returning to a previous state and trying a different path (much like a human clicking the back button and trying the next link). The impact of this reasoning-aware formulation was striking on e-commerce tasks – LASER nearly closed the gap with human performance on WebShop [13].

Reinforcement Learning

While prompting and supervised fine-tuning have seen success, another thread of research focuses on learning from experience to improve GUI agents. The idea is that by actually trial-and-error interacting with the environment, an agent can learn a policy that is more robust than one purely imitated from limited data. However, applying RL to large language model-based agents is non-trivial (due to huge action spaces, long horizons, and the expense of running many trials). Recent work has made progress on this front:

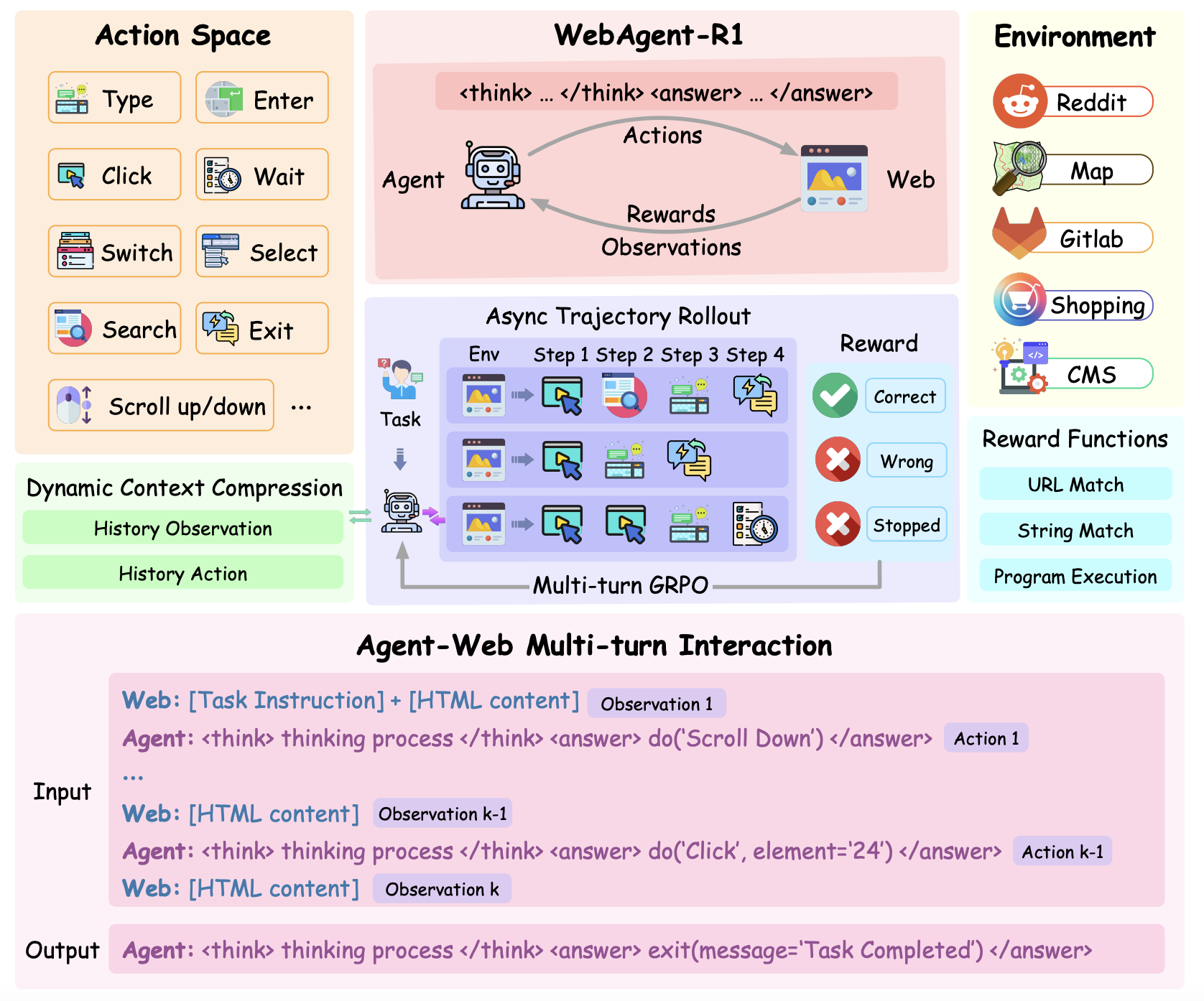

WebAgent-R1 (2025) [14] is an end-to-end RL framework that achieved state-of-the-art performance on WebArena by carefully adapting RL algorithms to LLM agents. The authors designed a reward function that encourages the agent to complete the task at hand while also exploring the web. They also introduced a method to handle the sparse and delayed reward signal present in web navigation tasks. One innovation in WebAgent-R1 is a dynamic context compression mechanism: as an episode proceeds through dozens of pages, the text observation can become thousands of tokens long (exceeding model limits). WebAgent-R1 dynamically truncates or compresses less relevant context from earlier steps to keep the input size manageable. Another contribution is extending GRPO [15] to multi-turn settings (called M-GRPO) and using asynchronous parallel browsing to collect experiences faster.

Overview of the end-to-end multi-turn RL training framework used in WebAgent-R1. We show an input/output example of agent–web interaction at the k-th step. The interaction continues until either the maximum number of steps is reached or the agent generates an exit() action to signal task completion. Source: [14]

Another angle of learning from experience is self-improvement via trajectory relabeling or self-play. Researchers have explored letting an LLM agent run on many tasks, then analyzing its failures and successes to generate additional training data [16]. The agent would attempt tasks, then (using the LLM’s own evaluation or a heuristic) identify where it went wrong, and synthesize corrected trajectories or critiques. These synthetic trajectories, added to a finetuning dataset, boosted the task completion rate by ~31% over the base model on WebArena. Such self-refinement approaches are appealing because they mitigate the need for large human-labeled datasets – the agent essentially learns from its mistakes. However, they also require careful validation to ensure the agent doesn’t reinforce bad behaviors.

In more recent literature, Agent Q [27] couples Monte-Carlo Tree Search with an LLM policy, augments each node with AI-feedback self-critique to densify sparse web rewards, and finally distills both winning and failing branches through Direct Preference Optimization; this “search-and-learn” loop boosts WebShop success to roughly 50 % and raises real-world OpenTable booking from 18 % to 81–95 %, surpassing GPT-4o and human baselines. InfiGUI-R1 [28] moves GUI agents from reactive clicking to deliberative reasoning via a two-stage Actor2Reasoner pipeline: Spatial Reasoning Distillation first implants explicit cross-modal reasoning traces, then RL-based Deliberation Enhancement rewards sub-goal planning and error recovery, producing a 3 B-parameter agent that matches or outperforms far larger models on ScreenSpot [29] grounding and long-horizon AndroidControl [31] tasks. Complementing these, UI-R1 [30] shows that a lean rule-based reinforcement fine-tuning regime—with a novel action-type/argument/format reward and GRPO on just 136 hard examples—can lift a 3 B Qwen-2.5-VL model by +22 pp on ScreenSpot and +12 pp on AndroidControl [31], rivaling much larger SFT models and even demonstrating that explicit reasoning can be skipped for simple grounding without loss of accuracy.

[Extra Credit Attempt] Running the RealWebAssist Benchmark with Qwen-2.5-VL

In this session, we integrated the Qwen-2.5-VL model into the latest open-source RealWebAssist benchmark for evaluation. We began by exploring the repository structure and understanding the existing evaluation pipeline. The evaluate.py script is the main entry point for running evaluations, and it imports various model scripts from the model_scripts directory. Each model script implements a get_coordinate function, which is called during evaluation to predict the coordinates of user interactions on web pages.

To integrate the Qwen-2.5-VL model, we created a new script named qwen_vl_baseline.py in the model_scripts directory. This script loads the Qwen-2.5-VL model using the transformers library and processes input data using the AutoProcessor and process_vision_info functions. The get_coordinate function in this script takes configuration data, history, base directory, and output directory as inputs. It constructs messages for the model, including the instruction and image path, and performs inference to generate output text. The output text is then parsed to extract the predicted coordinates.

We modified the evaluate.py script to include the Qwen-2.5-VL model by adding a block that imports the qwen_vl_baseline script and assigns its get_coordinate function. This function is called for each interaction in the dataset during evaluation. The script processes each episode, loading questions and history data, and calls the get_coordinate function to predict coordinates for click actions. The results are compared against ground truth bounding boxes to calculate accuracy and other metrics.

Results

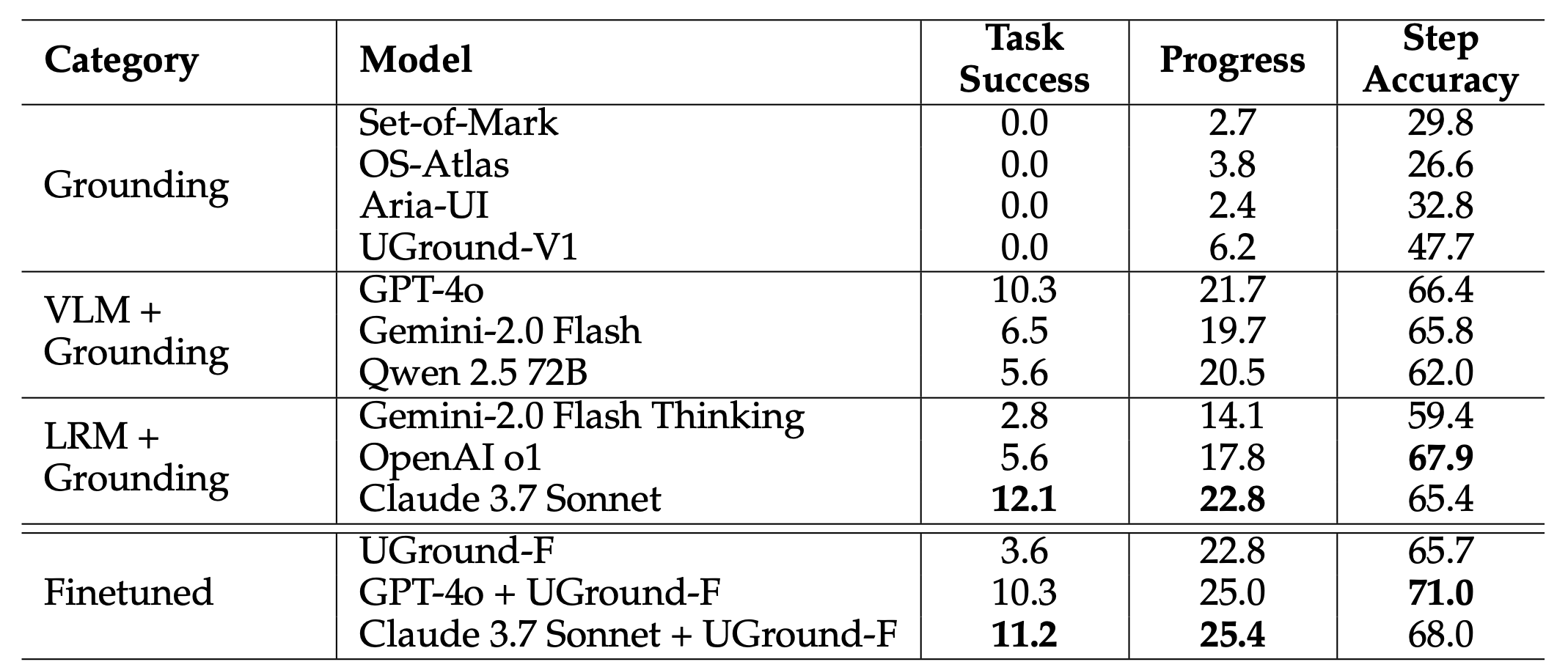

After setting up the evaluation pipeline, we ran the evaluation on episode 1 of the dataset. The dataset contains 225 interactions, of which 111 are click actions that require coordinate predictions. The evaluation results show that the Qwen-2.5-VL model correctly predicted 1 out of 111 click actions, resulting in an accuracy of approximately 0.9%. The average distance between predicted and actual coordinates was 516.14 pixels, and the task success rate was 0%, indicating that the model struggled to accurately predict the required coordinates for the tasks. The results highlight areas for potential improvement in the model’s performance on this benchmark. Due to limitations in our local compute resources, we were unable to run the evaluation on the entire dataset or with larger models. However, the authors of the RealWebAssist benchmark do provide results on some closed-source models.

Results from the RealWebAssist benchmark for closed-source models. Source: [32]

As we can see, even the state-of-the-art closed-source models like claude-3.7-sonnet struggled to achieve more than 11% accuracy on this benchmark. This is a very challenging benchmark and we believe that larger or finetuned versions of Qwen-2.5-VL model could perform better. We leave this as an open question for future work.

This is the raw json file for the results on episode 1 of qwen-2.5-vl-3b-instruct:

{

"overall": {

"total": 111,

"correct": 1,

"skipped": 114,

"accuracy": 0.9009009009009009,

"average_distance": 516.140350877193,

"average_progress": 0.6944444444444444,

"task_success_rate": 0.0

},

"episodes": {

"1": {

"total": 111,

"correct": 1,

"skipped": 114,

"accuracy": 0.9009009009009009,

"average_distance": 516.140350877193,

"average_progress": 0.6944444444444444,

"task_success_rate": 0.0

}

}

}

We attach the full code that we implemented for the Qwen-2.5-VL eval script here:

import torch

from transformers import Qwen2_5_VLForConditionalGeneration, AutoTokenizer, AutoProcessor

from qwen_vl_utils import process_vision_info

from PIL import Image

import re

import os

# Load model and processor globally

model = Qwen2_5_VLForConditionalGeneration.from_pretrained(

"Qwen/Qwen2.5-VL-32B-Instruct",

torch_dtype=torch.bfloat16,

attn_implementation="flash_attention_2",

device_map="auto",

)

# The default range for the number of visual tokens per image in the model is 4-16384.

min_pixels = 256*28*28

max_pixels = 1280*28*28

processor = AutoProcessor.from_pretrained("Qwen/Qwen2.5-VL-3B-Instruct", min_pixels=min_pixels, max_pixels=max_pixels)

count = 0

def parse_coordinates(output_text):

"""Parse coordinates from model output text."""

if isinstance(output_text, list):

output_text = " ".join(output_text)

# Look for various coordinate patterns: (x, y), [x, y], x,y, etc.

patterns = [

r"[\(\[](\d+),\s*(\d+)[\)\]]", # (x, y) or [x, y]

r"(\d+),\s*(\d+)", # x, y

r"x:\s*(\d+).*?y:\s*(\d+)", # x: 123, y: 456

r"x=(\d+).*?y=(\d+)", # x=123, y=456

]

for pattern in patterns:

match = re.search(pattern, output_text, re.IGNORECASE)

if match:

x, y = map(int, match.groups())

return (x, y)

# If no pattern matches, try to find any two numbers

numbers = re.findall(r'\d+', output_text)

if len(numbers) >= 2:

return (int(numbers[0]), int(numbers[1]))

raise ValueError("No valid coordinates found in the output text.")

def get_coordinate(config_data, history, base_dir, output_dir):

"""Main function that returns coordinates for the given instruction and image."""

global count

count += 1

try:

instruction = config_data.get("instruction", "")

image_path = config_data.get("final_image", "")

bounding_box_data = config_data.get("bounding_box", [])

if not bounding_box_data:

print(f"No bounding box data")

return None, None

print(f"Processing item {count}")

print(f"Image: {image_path}")

print(f"Instruction: {instruction}")

# Build the full image path

full_image_path = image_path # Path is already complete from config_data

if not os.path.exists(full_image_path):

print(f"Image not found: {full_image_path}")

return None, None

# Prepare the messages for the model

messages = [

{

"role": "user",

"content": [

{

"type": "image",

"image": full_image_path,

},

{

"type": "text",

"text": f"In this web page screenshot, I need to {instruction}. Please identify the exact pixel coordinates (x, y) where I should click to perform this action. Return the coordinates as (x, y)."

},

],

}

]

# Add history context if available

if history and history.strip():

messages[0]["content"].append({

"type": "text",

"text": f"Here is the previous interaction history for context:\n{history}"

})

# Preparation for inference

text = processor.apply_chat_template(

messages, tokenize=False, add_generation_prompt=True

)

image_inputs, video_inputs = process_vision_info(messages)

inputs = processor(

text=[text],

images=image_inputs,

videos=video_inputs,

padding=True,

return_tensors="pt",

)

inputs = inputs.to("cuda")

# Inference: Generation of the output

generated_ids = model.generate(**inputs, max_new_tokens=128)

generated_ids_trimmed = [

out_ids[len(in_ids) :] for in_ids, out_ids in zip(inputs.input_ids, generated_ids)

]

output_text = processor.batch_decode(

generated_ids_trimmed, skip_special_tokens=True, clean_up_tokenization_spaces=False

)

print(f"Raw model output: {output_text}")

# Parse coordinates from output

try:

coordinates = parse_coordinates(output_text[0] if output_text else "")

print(f"Parsed coordinates: {coordinates}")

return coordinates[0], coordinates[1]

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Failed to parse coordinates: {e}")

return None, None

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error in get_coordinate: {e}")

return None, None

Conclusion

GUI web agents are quickly becoming an important part of how we interact with the internet. Unlike earlier agents that only worked with text, these new agents can see and use websites much like a human would. They can click buttons, fill out forms, and follow instructions to complete real tasks online. But building a smart web agent isn’t just about giving it eyes and hands—it also needs a brain. It must be able to think ahead, make decisions, and fix mistakes when things go wrong. That’s why reasoning is such an important part of recent progress. Developers are finding better ways to help these agents plan, learn from experience, and solve harder tasks.

In this report, we explored how GUI web agents have become more advanced in recent years. We started by comparing them to earlier text-based agents and explained how working with images, layouts, and dynamic websites makes GUI agents much more complex. We then reviewed key benchmarks that help test and train these agents on realistic tasks, like browsing stores or navigating websites. We also looked at the powerful vision-language models that support these agents and the techniques used to connect what the agent sees to what it needs to do. Finally, we discussed how reasoning—planning steps, dealing with errors, and learning over time—is at the heart of making web agents truly useful. There’s still a long way to go before web agents can fully match human flexibility. But the progress so far shows real promise. With better tools, smarter models, and more realistic training, we’re getting closer to agents that can truly help people online—whether it’s shopping, searching, or assisting with everyday tasks.

References

[1] Nakano, Reiichiro, Jacob Hilton, Suchir Balaji, Jeff Wu, Long Ouyang, Christina Kim, Christopher Hesse et al. “Webgpt: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.09332 (2021).

[2] Yang, Ke, Yao Liu, Sapana Chaudhary, Rasool Fakoor, Pratik Chaudhari, George Karypis, and Huzefa Rangwala. “Agentoccam: A simple yet strong baseline for llm-based web agents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.13825 (2024).

[3] Hu, Minda, Tianqing Fang, Jianshu Zhang, Junyu Ma, Zhisong Zhang, Jingyan Zhou, Hongming Zhang, Haitao Mi, Dong Yu, and Irwin King. “WebCoT: Enhancing Web Agent Reasoning by Reconstructing Chain-of-Thought in Reflection, Branching, and Rollback.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.20013 (2025).

[4] Koh, Jing Yu, Robert Lo, Lawrence Jang, Vikram Duvvur, Ming Chong Lim, Po-Yu Huang, Graham Neubig, Shuyan Zhou, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, and Daniel Fried. “Visualwebarena: Evaluating multimodal agents on realistic visual web tasks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13649 (2024).

[5] Yang, Jianwei, Hao Zhang, Feng Li, Xueyan Zou, Chunyuan Li, and Jianfeng Gao. “Set-of-mark prompting unleashes extraordinary visual grounding in gpt-4v.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.11441 (2023).

[6] Deng, Xiang, Yu Gu, Boyuan Zheng, Shijie Chen, Sam Stevens, Boshi Wang, Huan Sun, and Yu Su. “Mind2web: Towards a generalist agent for the web.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (2023): 28091-28114.

[7] Xue, Tianci, Weijian Qi, Tianneng Shi, Chan Hee Song, Boyu Gou, Dawn Song, Huan Sun, and Yu Su. “An illusion of progress? assessing the current state of web agents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.01382 (2025).

[8] He, Hongliang, Wenlin Yao, Kaixin Ma, Wenhao Yu, Yong Dai, Hongming Zhang, Zhenzhong Lan, and Dong Yu. “WebVoyager: Building an end-to-end web agent with large multimodal models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13919 (2024).

[9] Ye, Suyu, Haojun Shi, Darren Shih, Hyokun Yun, Tanya Roosta, and Tianmin Shu. “Realwebassist: A benchmark for long-horizon web assistance with real-world users.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.10445 (2025).

[10] Achiam, Josh, Steven Adler, Sandhini Agarwal, Lama Ahmad, Ilge Akkaya, Florencia Leoni Aleman, Diogo Almeida et al. “Gpt-4 technical report.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 (2023).

[11] Yao, Shunyu, Jeffrey Zhao, Dian Yu, Nan Du, Izhak Shafran, Karthik Narasimhan, and Yuan Cao. “React: Synergizing reasoning and acting in language models.” In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR). 2023.

[12] Ma, Kaixin, Hongming Zhang, Hongwei Wang, Xiaoman Pan, Wenhao Yu, and Dong Yu. “Laser: Llm agent with state-space exploration for web navigation.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.08172 (2023).

[13] Yao, Shunyu, Howard Chen, John Yang, and Karthik Narasimhan. “Webshop: Towards scalable real-world web interaction with grounded language agents.” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (2022): 20744-20757.

[14] Wei, Zhepei, Wenlin Yao, Yao Liu, Weizhi Zhang, Qin Lu, Liang Qiu, Changlong Yu et al. “WebAgent-R1: Training Web Agents via End-to-End Multi-Turn Reinforcement Learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16421 (2025).

[15] Zhihong Shao, Peiyi Wang, Qihao Zhu, Runxin Xu, Junxiao Song, Xiao Bi, Haowei Zhang, Mingchuan Zhang, YK Li, Y Wu, and 1 others. 2024. Deepseekmath: Pushing the limits of mathematical reasoning in open language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.03300.

[16] Patel, Ajay, Markus Hofmarcher, Claudiu Leoveanu-Condrei, Marius-Constantin Dinu, Chris Callison-Burch, and Sepp Hochreiter. “Large language models can self-improve at web agent tasks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.20309 (2024).

[17] Team, Gemini, Rohan Anil, Sebastian Borgeaud, Jean-Baptiste Alayrac, Jiahui Yu, Radu Soricut, Johan Schalkwyk et al. “Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.11805 (2023).

[18] OpenAI. 2024. Introducing Operator. https://openai.com/index/introducing-operator/

[19] Anthropic. 2024. Anthropic’s new Claude 3.5 Sonnet model is now available. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-5-sonnet

[20] Bai, Shuai, Keqin Chen, Xuejing Liu, Jialin Wang, Wenbin Ge, Sibo Song, Kai Dang et al. “Qwen2. 5-vl technical report.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13923 (2025).

[21] Liu, Xiao, Bo Qin, Dongzhu Liang, Guang Dong, Hanyu Lai, Hanchen Zhang, Hanlin Zhao et al. “Autoglm: Autonomous foundation agents for guis.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.00820 (2024).

[22] Zheng, Boyuan, Boyu Gou, Jihyung Kil, Huan Sun, and Yu Su. “Gpt-4v (ision) is a generalist web agent, if grounded.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01614 (2024).

[23] Yunpeng Song, Yiheng Bian, Yongtao Tang, and Zhongmin Cai. 2023. Navigating Interfaces with AI for Enhanced User Interaction. ArXiv:2312.11190

[24] Yanda Li, Chi Zhang, Wanqi Yang, Bin Fu, Pei Cheng, Xin Chen, Ling Chen, and Yunchao Wei. 2024b. Appagent v2: Advanced agent for flexible mobile interactions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.11824.

[25] Zhang, Chaoyun, Liqun Li, Shilin He, Xu Zhang, Bo Qiao, Si Qin, Minghua Ma et al. “Ufo: A ui-focused agent for windows os interaction.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.07939 (2024).

[26] Agashe, Saaket, Jiuzhou Han, Shuyu Gan, Jiachen Yang, Ang Li, and Xin Eric Wang. “Agent s: An open agentic framework that uses computers like a human.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.08164 (2024).

[27] Putta, Pranav, Edmund Mills, Naman Garg, Sumeet Motwani, Chelsea Finn, Divyansh Garg, and Rafael Rafailov. “Agent q: Advanced reasoning and learning for autonomous ai agents.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.07199 (2024).

[28] Liu, Yuhang, Pengxiang Li, Congkai Xie, Xavier Hu, Xiaotian Han, Shengyu Zhang, Hongxia Yang, and Fei Wu. “Infigui-r1: Advancing multimodal gui agents from reactive actors to deliberative reasoners.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.14239 (2025).

[29] Li, Kaixin, Ziyang Meng, Hongzhan Lin, Ziyang Luo, Yuchen Tian, Jing Ma, Zhiyong Huang, and Tat-Seng Chua. “Screenspot-pro: Gui grounding for professional high-resolution computer use.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.07981 (2025).

[30] Lu, Zhengxi, Yuxiang Chai, Yaxuan Guo, Xi Yin, Liang Liu, Hao Wang, Han Xiao, Shuai Ren, Guanjing Xiong, and Hongsheng Li. “Ui-r1: Enhancing action prediction of gui agents by reinforcement learning.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.21620 (2025).

[31] Li, Wei, William Bishop, Alice Li, Chris Rawles, Folawiyo Campbell-Ajala, Divya Tyamagundlu, and Oriana Riva. “On the effects of data scale on computer control agents.” arXiv e-prints (2024): arXiv-2406.

[32] Ning, Liangbo, Ziran Liang, Zhuohang Jiang, Haohao Qu, Yujuan Ding, Wenqi Fan, Xiao-yong Wei et al. “A survey of webagents: Towards next-generation ai agents for web automation with large foundation models.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.23350 (2025).