Vision, Language, Action - The Robotics Trifecta Leveling Up AI Control

Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models have advanced robotic control by integrating multimodal understanding with action generation. This report systematically examines five representative VLA models—RT-1, RT-2, OpenVLA, TinyVLA, and diffusion-based policies—focusing on their architectures, datasets, and inference strategies. We highlight their strengths and limitations in areas such as real-time control, generalization, and scalability. Drawing on a comparative analysis, we identify ongoing challenges including data diversity, hierarchical reasoning, and safety evaluation. Finally, we propose future directions to improve VLA models’ robustness, efficiency, and applicability in real-world robotics. Our synthesis provides a roadmap for researchers aiming to develop scalable, interpretable, and reliable embodied AI systems.

- Introduction

- Background and Related Work

- Model Review: From RT1 to Diffusion Based policies

- 4. Model Breakdown

- 5. Challenges and Future Directions

- 6. Additional Resources

- 7. References

Introduction

Recent advances in robotics increasingly favor unified models that integrate perception, reasoning, and control into a single framework. Traditional robotic pipelines rely on modular components—object detectors, planners, and controllers—that are independently engineered. While modularity offers flexibility, it often leads to error propagation, limited generalization, and costly system integration.

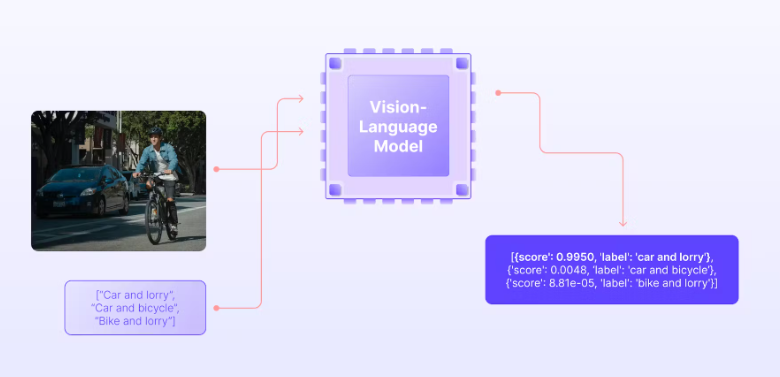

Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models address these challenges by directly mapping raw sensory inputs and natural language instructions to robot actions end-to-end. Leveraging Transformer-based architectures trained on large datasets, these models generalize across diverse tasks, robots, and environments. This approach builds on successes in vision-language models (VLMs) and large language models (LLMs) in areas such as image captioning, vision-language pretraining, and instruction-following.

Image Credit: Encord

The RT series pioneered this field, with RT-1 demonstrating large-scale behavior cloning from over 130,000 robot episodes, establishing a strong multi-task baseline. RT-2 advanced this by co-training on web-scale vision-language data and robotic control, enabling emergent abilities like object attribute reasoning and compositional generalization beyond the robot data alone.

Despite their breakthroughs, RT models remain closed-source and computationally demanding. OpenVLA responded by releasing an open-source, instruction-following VLA trained on nearly a million robot demonstrations across multiple embodiments, offering an accessible and modular foundation for research and deployment.

Simultaneously, resource-efficient alternatives like TinyVLA and diffusion-based policies (e.g., π₀) focus on real-time, high-frequency control without sacrificing generalization. This survey comprehensively compares RT-1, RT-2, OpenVLA, TinyVLA, and Diffusion-VLA, supplemented by an OpenVLA demo to highlight practical capabilities and design trade-offs in embodied AI.

Background and Related Work

To understand the advances in Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models, it is important to review the foundational concepts and prior research that have shaped this field. Traditional robotics pipelines established the modular approach to perception, planning, and control, while behavior cloning introduced early end-to-end learning techniques for robot control. More recently, breakthroughs in vision-language models (VLMs) and embodied instruction-following agents have expanded the capabilities of robots to interpret and act upon natural language instructions in complex environments. The availability of large-scale multimodal robotics datasets has been critical in enabling the training and evaluation of generalist VLA models. This section surveys these key developments to provide the necessary context for the models analyzed in this work.

2.1 Classical Robotics Pipelines

Traditional robotics systems are typically constructed as modular pipelines composed of three stages: perception, planning, and control. The perception module extracts semantic information from visual or sensor data; the planner generates symbolic or geometric plans; and the controller executes the trajectory on hardware. While this approach enables structured reasoning and human interpretability, it requires extensive system engineering and manual tuning for each domain. Moreover, the modular separation makes these systems brittle to distribution shifts and multi-task generalization [18].

2.2 Behavior Cloning and End-to-End Learning

End-to-end robot learning emerged to address these challenges by directly mapping raw observations to actions using neural networks. Behavior Cloning (BC), where models are trained via supervised learning on expert demonstrations, was one of the earliest paradigms for imitation learning [17]. Though simple and effective, BC often struggles with covariate shift in long-horizon tasks and lacks sample efficiency.

2.3 Vision–Language Models (VLMs)

Recent breakthroughs in Vision–Language Models (VLMs) such as CLIP [8] and BLIP-2 [9] have significantly improved the ability to ground textual instructions in visual context. These models are typically pretrained on large-scale web data and fine-tuned for downstream multimodal tasks, such as VQA, captioning, and image retrieval. Their strong representational capabilities and compositional reasoning have inspired their adaptation to the robotics domain.

2.4 Embodied Instruction-Following Agents

Embodied instruction-following tasks aim to connect language and visual understanding with agent behaviors in simulated or real environments. Early benchmarks include ALFRED [10] and Habitat [11], which involve agents navigating and manipulating environments based on natural language goals. These simulations have served as testbeds for language-conditioned policies and policy transfer, but they lack the physical realism of robotics control.

2.5 Multimodal Robotics Datasets

The success of large-scale VLA models depends on the availability of diverse, high-quality datasets. The RT-1 dataset [1] introduced over 130k robot episodes across multiple tasks. More recently, the Open X-Embodiment dataset [4] unified demonstrations from 22 different robot platforms, enabling large-scale pretraining across diverse morphologies. Other benchmarks such as LIBERO [12] and Maniskill2 [13] continue to push toward standardized, open-access training and evaluation platforms for generalist robots.

Model Review: From RT1 to Diffusion Based policies

This section reviews five influential Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models—RT-1, RT-2, OpenVLA, TinyVLA, and Diffusion-VLA / π₀—summarizing their architectures, training data, key strengths and limitations, and appropriate use cases.

3.1 RT‑1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control

RT-1 [1] was the first large-scale Transformer-based model trained end-to-end on real robot demonstrations. It processes images and instructions to predict discrete low-level robot actions, showing strong generalization despite task-specific vocabularies.

- Architecture: Transformer encoding fused visual and language tokens; outputs quantized low-level robot actions.

- Training Data: Over 130,000 teleoperated robot episodes covering 13 distinct tasks.

- Performance: Demonstrated good zero-shot generalization to unseen task configurations and objects.

- Limitations: Requires significant task-specific data and vocabularies; limited reasoning ability.

- When to Choose: Suitable for real-world robot control tasks with ample domain-specific data and when modular pipelines are infeasible.

3.2 RT‑2: Bridging Vision–Language and Action

RT-2 [2] integrates large pretrained vision-language models with robot control policies, enabling emergent reasoning abilities and compositional instruction following by co-training on web-scale image-text and robot data.

- Architecture: Frozen Vision Transformer (ViT) encoder; co-trained autoregressive decoder producing action tokens.

- Training Data: Combination of internet-scale image-text pairs (e.g., LAION) and real robot demonstrations.

- Performance: Exhibits emergent capabilities such as object attribute reasoning and chain-of-thought action sequences.

- Limitations: Very large (~55B parameters), high inference latency, and closed-source.

- When to Choose: Best for research requiring state-of-the-art reasoning and generalization but with ample compute and no need for open-source access.

3.3 OpenVLA: The First Open-Source VLA Model

OpenVLA [3] offers a smaller, fully open-source VLA model trained on a massive multi-robot dataset, balancing performance, modularity, and accessibility.

- Architecture: Combines pretrained vision encoders (DINOv2, SigLIP) with an LLaMA-2-7B language model core policy.

- Training Data: ~970,000 episodes from 22 robot embodiments and 527 diverse tasks.

- Performance: Outperforms larger RT-2-X on multiple benchmarks despite smaller size.

- Fine-Tuning: Supports parameter-efficient fine-tuning (PEFT) and quantization (e.g., QLoRA) for deployment.

- Limitations: Lacks web-scale pretraining; slower on high-frequency control compared to diffusion-based models.

- When to Choose: Ideal for open research, real-world deployments needing multi-robot generalization and fine-tuning capabilities.

3.4 TinyVLA: Lightweight and Fast Instruction-Following

TinyVLA [5] targets resource-constrained environments by prioritizing model compactness and fast inference, sacrificing some generalization for real-time responsiveness.

- Architecture: Smaller vision backbones combined with diffusion-based decoder generating action trajectories.

- Training Data: Trained on smaller datasets optimized for efficiency.

- Performance: High inference speed optimized for real-time tasks like grasping.

- Limitations: Slight reduction in task generalization compared to larger VLA models.

- When to Choose: Suitable for embedded or edge deployments requiring low latency and fast control with limited compute.

3.5 Diffusion-VLA / π₀: High-Frequency and Robust Control

Recent efforts like Diffusion-VLA [7] and π₀ [6] explore generative policies that generate smooth, continuous action sequences for high-frequency closed-loop control, excelling in complex, dexterous manipulation.

- Architecture: Generative diffusion or flow-matching decoders conditioned on vision and language inputs.

- Training Data: Large datasets covering multi-step, continuous action tasks.

- Performance: Achieves inference rates up to 82 Hz; robust long-horizon control with smooth trajectories.

- Limitations: Complex training and inference with denoising schedules; potential training instability.

- When to Choose: Best for high-speed, dexterous robotic control where smoothness and robustness are critical.

4. Model Breakdown

4.1 Comparison Table

The below table compares five key Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models across size, data requirements, decoder type, inference speed, and strengths. RT‑1 showed that large-scale behavior cloning could work in the real world. RT‑2 built on this with web-scale training, enabling better reasoning but requiring far more compute. OpenVLA offers a middle ground—it’s open-source, smaller, and still achieves strong performance. TinyVLA and π₀ focus on fast, smooth control using diffusion-based decoders, which makes them ideal for real-time tasks on edge devices. These models reflect different design priorities: some aim for accuracy and generalization, while others prioritize speed and efficiency. This table helps identify which models make sense depending on deployment goals, available compute, and the nature of the task.

| Model | Parameters | Data Size | Decoder | Inference Speed | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT‑1 | ~1–5B | 130k demos | Discrete | Moderate | Strong multi-task baseline |

| RT‑2 | ~55B | Web-scale + real-world demos | Discrete / Sequential | Low | Web-scale knowledge, symbolic reasoning |

| OpenVLA | 7B | 970k demos (22 robot types) | Discrete | Moderate | Open-source, strong generalization |

| TinyVLA | <7B | Small-scale real-world demos | Diffusion-based | High | Compact, efficient, fast inference |

| Diffusion-VLA / π₀ | 2–72B | Large pretraining + fine-tuning | Diffusion / Continuous | Very High (50–82 Hz) | Smooth trajectories, dexterous control |

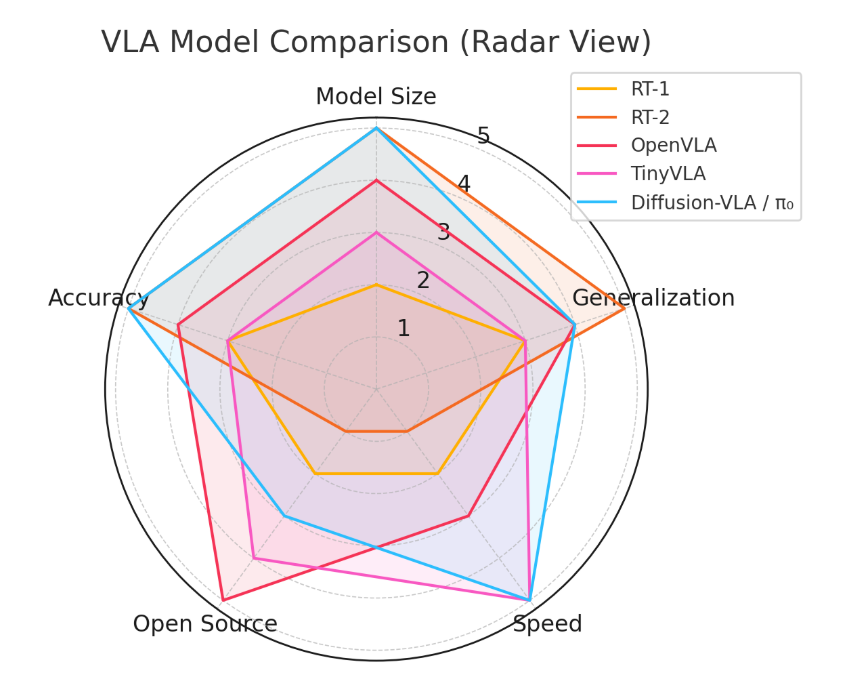

4.2 Radar Plot: Qualitative Comparison

The radar chart below compares all five models on five normalized axes: model size efficiency, generalization, inference speed, open-source availability, and task accuracy. Figure 1: Radar-style comparison of five VLA models on qualitative metrics. Values are normalized for interpretability (higher is better).

Radar-style comparison of five VLA models on qualitative metrics. Values are normalized for interpretability (higher is better)

4.3 Key Takeaways

👉 RT‑2 remains the most capable model in terms of reasoning and generalization. By combining robot demonstrations with web-scale vision–language pretraining, it can follow complex instructions and infer abstract goals. However, its large size (~55B parameters), lack of open-source availability, and heavy computational requirements make it harder to deploy or adapt in practical settings.

👉 OpenVLA strikes a strong balance between performance and accessibility. It is open-source, significantly smaller than RT‑2, and still matches or surpasses its performance on several test tasks. This makes it highly suitable for both academic research and scalable deployment in applied systems.

👉 TinyVLA and π₀ shift the focus from large-scale generalization to fast, responsive control. They use lightweight architectures and diffusion-based decoding to support high-frequency inference, which is critical for real-time robotics tasks on constrained hardware. Their speed and efficiency make them attractive for edge applications, although they may trade off some task generality.

👉 Diffusion-based policies like Diffusion-VLA and π₀ also offer smooth and robust trajectory generation, especially useful for dexterous manipulation or long-horizon tasks where consistency and stability are essential.

Overall, no single model dominates across all axes. Each system represents different trade-offs among accuracy, inference speed, data scale, and resource cost. These trade-offs remain central to ongoing research in building more capable and deployable VLA systems.

5. Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the rapid progress in Vision–Language–Action (VLA) models, several challenges remain before these systems can be deployed reliably in real-world robotics. These issues span inference efficiency, data diversity, generalization, and safe deployment. Addressing them is key to unlocking scalable, generalist robotic agents.

5.1 Real-Time Inference and Hardware Efficiency

Large-scale VLA models like RT‑2 and OpenVLA leverage transformer architectures and autoregressive decoders, introducing significant inference latency. This latency becomes a bottleneck in closed-loop control tasks where sub-second decision-making is essential. For example, RT‑2 must generate multiple tokens per action step, limiting its control frequency to under 5 Hz [1]. In contrast, diffusion-based models such as π₀ achieve inference rates between 50–82 Hz, enabling real-time dexterous control [6].

Future directions may include compact model designs, use of efficient attention mechanisms, and deployment optimizations such as model pruning, quantization (e.g., QLoRA [16]), or parameter-efficient tuning strategies (e.g., LoRA [15]) to support fast inference on edge hardware.

5.2 Data Diversity and Embodiment Generalization

While datasets like Open X-Embodiment [4] span a broad range of tasks and morphologies, most demonstrations rely on teleoperated trajectories and have limited language variation. This restricts the language-action grounding diversity required for robust generalization. Additionally, models trained on specific robot embodiments often fail to transfer effectively across unseen morphologies or sensors.

Improving cross-platform generalization may require domain adaptation techniques, skill abstraction layers, or multi-view policy alignment. Simulation-to-real transfer remains a promising but open area, especially for rare or unsafe real-world tasks [20].

5.3 Compositional Generalization and Hierarchical Planning

Most current VLA models operate at the level of low-level action prediction. While RT‑2 demonstrates early capabilities in object-based reasoning, it lacks a notion of explicit subgoal structuring or multi-step planning. Without compositional or hierarchical abstraction, long-horizon tasks remain brittle and require extensive demonstrations.

One promising direction involves integrating LLMs for high-level symbolic planning, while keeping low-level controllers focused on actuation and precision. Architectures such as LLaRA [7] and Code-as-Policies [19] explore this split between semantic and physical layers, allowing planning in natural language or code, followed by grounding in motor space.

5.4 Evaluation and Safety Standards

There is no universally adopted benchmark for evaluating VLA models across varied robot platforms, real-world scenarios, and safety criteria. Current evaluations are often based on custom task suites and controlled lab setups, which may not reflect deployment challenges. Benchmarks like LIBERO [12], Calvin [14], and ManiSkill2 [13] provide early steps toward standardization, but remain limited in scope or realism.

In safety-critical domains, such as assistive or collaborative robotics, it is crucial to embed reliability, calibration, uncertainty estimation, and fallback strategies. Yet integrating these into end-to-end policies—especially those derived from web-scale pretraining—remains an unsolved challenge.

5.5 Open Research Directions

Several emerging directions could shape the next wave of progress in VLA systems:

- Multimodal Memory: Leveraging persistent, context-aware memory to support multi-turn tasks and lifelong learning.

- Few-shot / Zero-shot Adaptation: Adapting to unseen tasks via prompts, language sketches, or minimal interaction.

- Social Reasoning: Understanding human intentions, emotions, and contextual cues for better human-robot collaboration.

- Cloud–Robot Collaboration: Using hybrid architectures where large models run in the cloud and edge devices handle latency-sensitive components.

- Self-improving Loops: Enabling continuous improvement through online learning, reward distillation, or feedback-informed policy shaping.

These challenges reflect not just technical bottlenecks but fundamental design trade-offs in building capable, safe, and adaptable robotic systems.

6. Additional Resources

For readers interested in exploring the Vision–Language–Action models further, here are official project pages for detailed documentation:

7. References

[1] Brohan, A., Brown, N., Chebotar, Y., et al. (2022). RT-1: Robotics Transformer for Real-World Control at Scale. arXiv:2212.06817.

[2] Brohan, A., Ichter, B., Lee, J., et al. (2023). RT-2: Vision-Language-Action Models Transfer Web Knowledge to Robotic Policies. arXiv:2307.15818.

[3] Yan, L., Liu, S., Xie, A., et al. (2024). OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model. OpenVLA Project Website. https://openvla.github.io/.

[4] Duan, Y., Levine, S., Lynch, C., et al. (2023). Open X-Embodiment: Robotic Learning Datasets and Benchmarks at Scale. arXiv:2309.16610.

[5] Kim, J., Sermanet, P., Abbeel, P., et al. (2024). TinyVLA: Towards Fast, Data-Efficient Vision-Language-Action Models. arXiv:2403.09711.

[6] Singh, R., Xu, D., Zeng, A., et al. (2023). π₀: A Policy for Dexterous Manipulation with Flow-Matching. arXiv:2312.00841.

[7] Xie, A., Wang, B., Yan, L., et al. (2024). Diffusion Policies for Robotic Manipulation. arXiv:2210.05695.

[8] Radford, A., Kim, J., Hallacy, C., et al. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision (CLIP). arXiv:2103.00020.

[9] Li, J., Hu, K., Lin, Z., et al. (2023). BLIP-2: Bootstrapping Language-Image Pre-training with Frozen Image Encoders and Large Language Models. arXiv:2301.12597.

[10] Shridhar, M., Manuelli, L., and Fox, D. (2020). ALFRED: A Benchmark for Interpreting Grounded Instructions for Everyday Tasks. arXiv:1911.01774.

[11] Savva, M., Chang, A. X., Dosovitskiy, A., et al. (2019). Habitat: A Platform for Embodied AI Research. arXiv:1904.01201.

[12] Yao, T., Batra, D., Zhu, Y., et al. (2023). LIBERO: Benchmarking Knowledge Transfer for Robotic Manipulation. arXiv:2309.06683.

[13] Gu, S., Li, H., Lin, K., et al. (2023). ManiSkill2: A Unified Benchmark for Generalizable Manipulation Skills. arXiv:2304.14459.

[14] Mees, O., Lampert, C. H., and Burgard, W. (2022). CALVIN: A Benchmark for Language-Conditioned Policy Learning for Long-Horizon Robot Manipulation Tasks. arXiv:2204.01995.

[15] Hu, E., Shen, Y., Wallis, P., et al. (2022). LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models. arXiv:2106.09685.

[16] Dettmers, T., Pagnoni, A., Holtzman, A., and Zettlemoyer, L. (2023). QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs. arXiv:2305.14314.

[17] Pomerleau, D. (1989). ALVINN: An Autonomous Land Vehicle in a Neural Network. NIPS 1989.

[18] Sutton, R. (2019). The Bitter Lesson. Essay. http://www.incompleteideas.net/IncIdeas/BitterLesson.html.

[19] Liang, J., Huang, W., and Xia, F., et al. (2022). Code as Policies: Language Model Programs for Embodied Control. arXiv.2209.07753.

[20] Peng, X., Andrychowicz, M., and Zaremba, W., et al. (2018). Sim-to-Real Transfer of Robotic Control with Dynamics Randomization. arXiv.1710.06537