Pong on Fire: Evaluating LLaVA's Potential as a Gaming Adversary

In this study, I take a deep dive into LLaVA—a state-of-the-art large vision-action language model with robust general purpose visual and language understanding in a chat context—and its capabilities in Pong to extrapolate the potential of using generalist LMMs as gaming agents. This firstly involves an investigation into LLaVA’s general purpose capabilities, followed by an exploration of LLaVA family models, with a focus on LLARVA, a LLaVA-inspired model for robot learning. Upon examination, it is clear that LLaVA demonstrates great capabilities across a variety of domains, and LLaVA-inspired models similary demonstrate enhanced capabilities when further designed around and fine-tuned for downstream tasks. I thus evaluate LLaVA on its ability to provide accurate inputs for the video game Pong based on a set of frames of gameplay. I successfully used a pre-trained LLaVA model to provide action responses when prompted, and though compute resources and time constrained my ability to generate more test data, a manual evaluation of the results demonstrated that LLaVA had the capability to correctly assess where to move its paddle and additionally reason about why it made the action it did. While these results are not definitive, this work showcases the potential for vision language models to be performant at tasks involving a variety of stimuli and complex control.

- Introduction

- Prior Works

- Problem Formulation

- Experimental Methods and Evaluation

- Results

- Discussion

- Conclusion

- Links

- References

Introduction

Over the past few years, large language models (LLMs) have taken the world by storm, with OpenAI reporting that ChatGPT has hundreds of millions of actively users monthly. In that time, LLMs have not only significantly improvied their performance and accuracy with a variety of tasks, but they’ve also evolved to handle a wider variety of complex tasks involving language, from machine translation to coding assistance and even therapy. Naturally, as these models became more powerful, research has also attempted to develop models that we can interact with in modes beyond simply language. These models, known broadly as large multimodal models, can take a variety of types of input, such as images, video, audio, and text, and generate content involving one or multiple of these modes.

Vision-action language models, in particular, are a subset of large multimodal models (LMMs) specifically trying to cohesively combine computer vision capabilities with the robust language capabilities of large language models. Recent advances in LLM capabilities have coincided with greater LMM capabilities, with new versions of existing LLMs such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini gaining significant multimodal functionality. While these models are certainly powerful and present a step above LLMs, they currently are still a pretty nascent technology, meaning that there is a variety of research and methods exploring possibilities for improving LMMs.

LLaVA[1] was one of the first end-to-end, open source LMMs, fine-tuned specifically for instructions involving visual context. End-to-end in this case means that the model was developed to handle visual and language from input to output, by specifically utilizing a two-pronged architecture combining a vision encoder with an LLM for its general purpose vision and language understanding. Users can interact with a LLaVA model via chat capabilities in a similar fashion to models like ChatGPT. Importantly, as the model is open source, it allows members of the public such as myself to train and fine-tune the model on my own. Models such as and inspired by LLaVA have been utilized on a variety of downstream tasks.

To evaluate its capabilities and explore the use of LMMs in tasks involving visual stimuli and complex controls, I test LLaVA’s capabilities at providing actions for Pong. Atari’s Pong has long been used as a task for evaluating Reinforcement Learning algorithms as part of OpenAI’s baselines. While my evaluation of LLaVA’s capabilities at playing Pong are not fully comprehensive, they provide a meaningful first step towards demonstrating the capability of LMMs at playing video games.

Prior Works

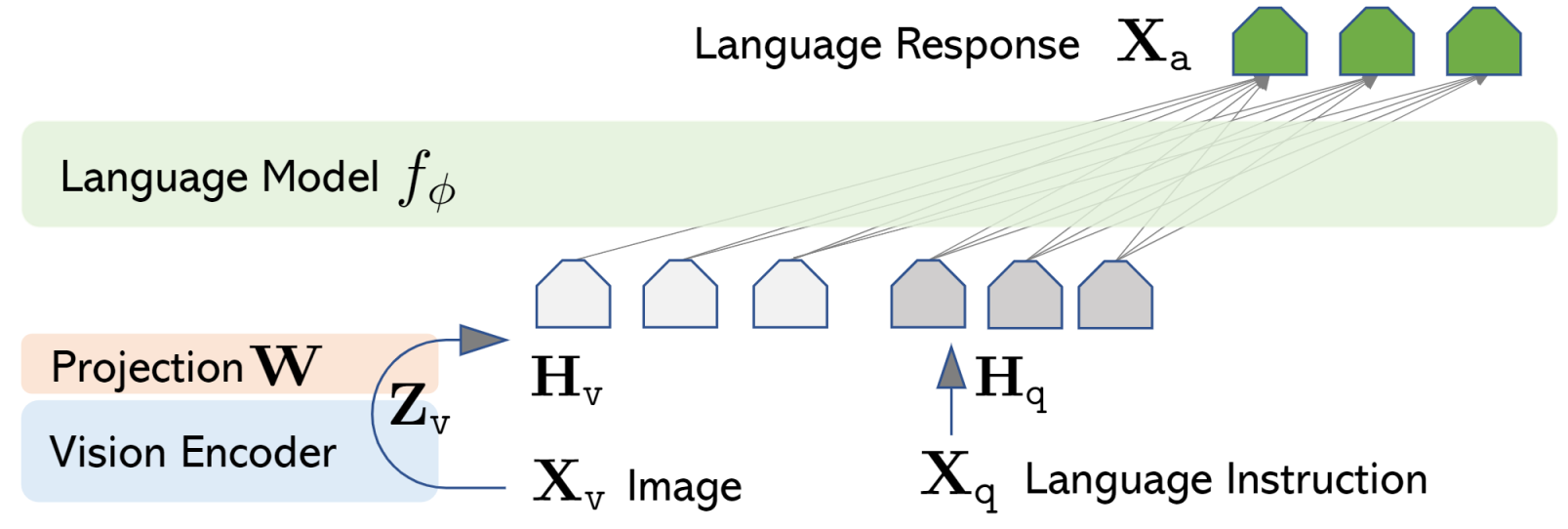

LLaVA

As mentioned previously, LLaVA[1] is an end-to-end, open source large multimodal model. LLaVA connects two open-source models, the CLIP visual encoder and Vicuna large language model, via a projection matrix. Image inputs are processed by the visual encoder before being projected into a shared language space alongside text input. These combined inputs are then processed by the language model to provide a visual context-aware language response. This is their core innovation, which they call “visual instruction tuning,” essentially utilizing the image input as a direct input to the large language model. The projection matrix is pre-trained on a large multimodal dataset, before being fine-tuned towards two use scenarios: Visual Chat, a general-purpose instruction-following application for responses to user prompts akin to GPT-like models, and Science QA, dedicated for multimodal reasoning in the science domain.

Fig. 1, Architecture of LLaVA

My work primarily takes advantage of LLaVA’s capabilities in Visual Chat. By providing a structured prompt alongside visual input, LLaVA demonstrates an ability to reason through complex tasks, including playing Pong. While other models have a variety of additional capabilities or may be more robust in their capabilities, LLaVA was relatively lightweight (enough to run on locally on my machine), which made it suitable for the simple Pong task.

LLARVA

LLARVA[2] is a robot learning model built around LLaVA’s visual instruction tuning architecture, taking it a step further with what they called “vision-action instruction tuning.” Using a structured prompt, they were able to extend upon LLaVA’s visual visual instruction tuning by embedding key information into their prompting: robot model, control mode, robot task, proprioceptive information, and number of predicted steps. This additional information helps them develop a 2-D visual trace, which is used by the model to guide the end effector arm of a robot towards its end goal.

Fig. 2, Vision-Action Instruction Tuning in LLARVA

The LLARVA architecture similarly utilizes a visual and language input which are mapped to the same projection space, according to LLaVA 1.5’s implementation[3]. Their addition of structured prompts inspired my use of a less complex, but still structured prompt which provides additional information and reasoning to tune LLaVA’s response to Pong frames. Initially, I wanted to run a more robust experiment using LLARVA, however the compute power, memory, and time necessary to run my own experiments with LLARVA exceeded the resources I had available with my machine.

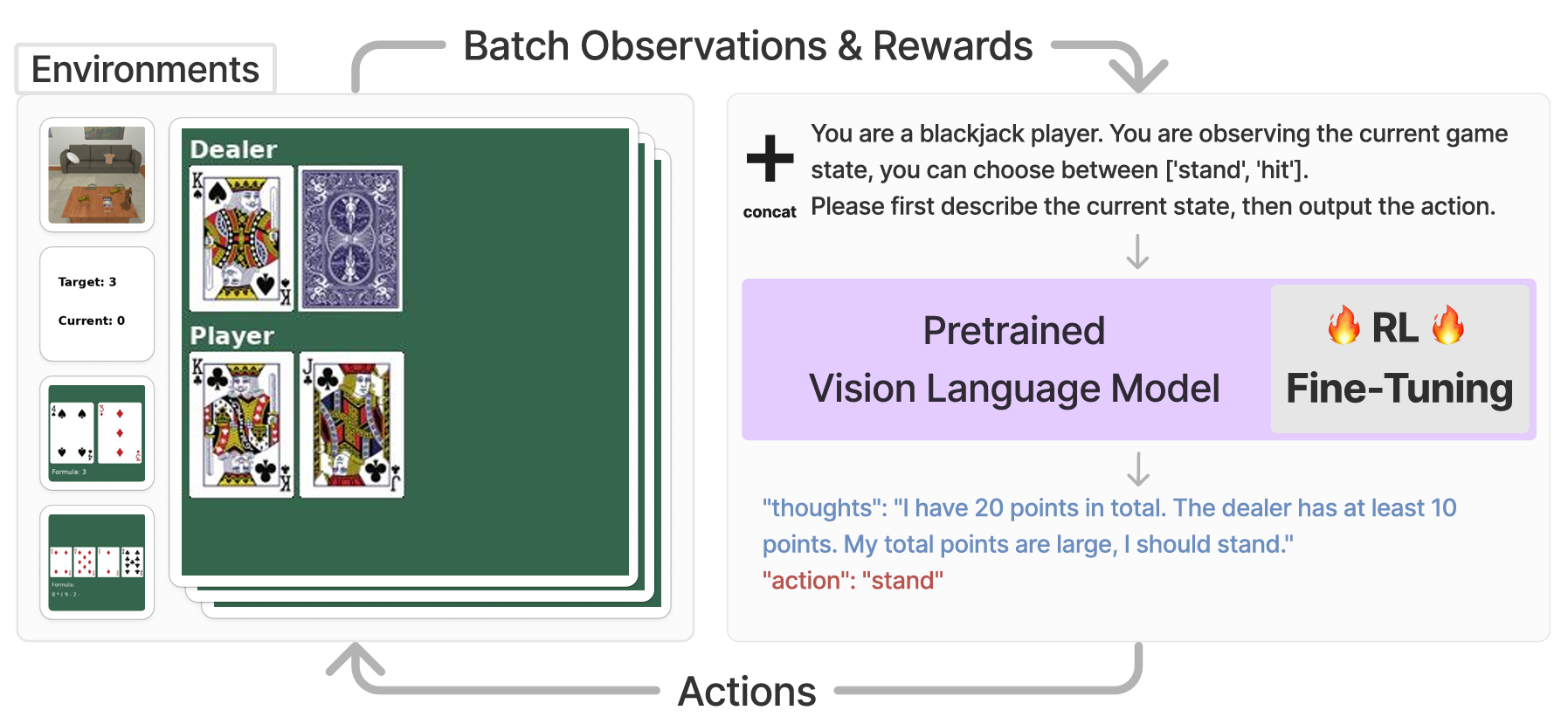

Vision-Language Models as Decision Making Agents via Reinforcement Learning

A previous paper utilizing vision-language models and reinforcement learning[4] demonstrated a proof-of-concept framework that enabled vision-language models to interact with an environment to make decisions in a game setting such as for playing card games such as Blackjack. They discovered that chain-of-thought reasoning proved critical in improving performance beyond base versions of commercial models such GPT-4 or Gemini. While I did not utilize reinforcement learning or chain-of-thought reasoning directly in my evaluation, this paper demonstrates another method of utizing a large multimodal model for decision making in games.

Fig. 3, VLM-RL Decision Making Agent Method Overview

These chain-of-thought reasoning models, as well as other approaches, similarly present viable options for future work in decision making agents. However, chain-of-thought models, similar to LLARVA, would have been too heavyweight to train and run locally, and they additionally would not be as feasible for faster decision making in a video game environment like Pong. While I ultimately did not use real-time action inference, prompting a chain-of-thought model for Pong actions, while likely more accurate, would have taken significantly longer.

Problem Formulation

I contribute a novel downstream task utilization for LLaVA as an extension of its general-purpose capabilities to video game control. Using a structured prompt and frames of Pong gameplay as input, I test whether the LLaVA model can successfully reason about where to move its paddle in order to hit the ball back and hopefully score a point.

The environment is a simple Pong game, where the user controls the leftmost orange paddle, and the LLaVA model is tasked to play as the rightmost green paddle. In Pong, there are essentially 3 possible actions at any given timestep—move up, move down, or don’t move at all. The expectation is that given a set of frames from a random section of Pong gameplay, the LLaVA model should develop an understanding of which direction the ball is moving, and thus determine whether its paddle needs to move up, down, or stay still in order to hit the ball back to the user. This understanding is evaluated via the additional reasoning the LLaVA model is prompted to provide in addition to its chosen action.

This work contributes to the growing evaluation of downstream applications of large language models, as well as to utilizations for the growing family of LLaVA models.

Experimental Methods and Evaluation

I utilized the SOTA LLaVA 1.5 model[3] with 7 billion parameters and load its pre-trained weights locally to my machine. To generate the frames, I utilize the Arcade Learning Environment[5] to emulate a game of Pong. I then sample 3 frames of gameplay at 20 timestep intervals 25 times, for a total of 75 frames. Each of these 25 groups of frames are then provided as the visual input for the LLaVA model.

Fig. 4, A group of frames of Pong gameplay

For the language input, my main insight involves using a structured prompt in a similar fashion to LLARVA’s structured prompt, albeit with less key information. To interact with the LLaVA model, I set up a two-fold prompt, with the first prompt being a system prompt detailing to the model the setup of the game environment and its task to try to hit the ball back towards the player. I then prompt the the model to respond with one of three different possible actions—“up”, “down”, or “none”—and provide a reasoning for why it chose the action.

You are an AI Pong Player using keyboard controls who also provides reasoning after each input.

The task is to hit the ball back to the opponent (the user, who is playing with orange on the left side),

not letting the ball hit your side of the screen (you are the player are on the right side in green).

You can move up or down to hit the ball. You will be shown a series of 3 frames from the game by the user.

Respond to the user's images and analyze each frame and provide a two-part response:

First, respond in with which action you will take in the frame after the last of the 3 frames:

- "up" to move the paddle up

- "down" to move the paddle down

- "none" to stay in place

Secondly, explain why you chose "up", "down", or "none".

My system prompt for LLaVA

Then, I prompt the model through a user chat with one of the groups of Pong gameplay frames and ask the model for its response. Each response took around 30 seconds to a minute on my local machine.

messages = [

{

"role": "system",

"content": [

{"type": "text", "text": ...prompt from above...}

]

},

{

"role": "user",

"content": [

{"type": "text", "text": f"""I will provide you with

3 frames from the game. What is your next move?

"""},

{"type": "image", "path": ...path_to_frame_1...},

{"type": "image", "path": ...path_to_frame_2...},

{"type": "image", "path": ...path_to_frame_3...}

]

}

]

Multimodal chat input

I then store the image frames and their corresponding LLaVA model outputs within an output folder for evaluation. I then manually parsed each of the 25 outputs for my evaluation to provide a ground truth and compare the model’s actions choice versus my own.

While this method is the final method that I settled upon, I had tried a few other methods to less success. My initial attempt utilized no system prompt and only a user prompt asking for one of 3 actions based on only one frame of gameplay. I discovered that this initial method led to pretty erratic results, and realized that I needed some idea of ball trajectory in order to better improve the model, which is what inspired using 3 frames of gameplay per prompt. Furthermore, variations of the user prompt would either inconsistently yield one word responses of the action the model would take, without any reasoning, or long-winded responses with no clear action. Shifting the setup portion of the prompt to a system prompt instead provided greater consistency in the responses.

Results

Generally, I discovered that the LLaVA model was typically successful at determining the correct action to take, making a correct or plausible action on 16 of 25 frame groups. This isn’t spectacular performance, but given the relatively minimal setup, I believe it demonstrates a positive starting point for the model, along with significant room for improvement. Fig. 5 and Resp. 1 indicate an ideal response given the input.

Fig. 5, A group of frames of Pong gameplay

In the first frame, the paddle is positioned above the ball. In the second frame, the

paddle is moving down to hit the ball. In the third frame, the paddle is about to make

contact with the ball. Based on these frames, my next move would be to move the paddle

down to hit the ball, aiming to return it to the opponent's side of the screen.

Resp. 1, LLaVA's response

There are a few notable observations I had when comparing my desired actions with the

model’s actions. In cases where the model could have chosen a “none” action, the model

never did, instead favoring an up or down action regardless. In 6 instances, moving as

well as not moving would have both been valid responses, so I considered these instances

plausible actions. Additionally, there were 2 responses where the model misinterpreted

the visual inputs and as a result hallucinated a response that didn’t include one of

the actions that I prompted it for. Fig. 6 and Resp. 2 give an example of what a

hallucinated response looked like. While the model did successfully identify correct

actions more often than not, there were times when the reasoning provided did not

exactly line up with the input frames as well or the model did not provide full

reasoning for its action, which can be see in Fig. 7 and Resp. 3.

Fig. 6, A group of frames of Pong gameplay

In the first frame, the paddle is positioned at the top left corner of the screen. In

the second frame, the paddle is at the top right corner of the screen. In the third

frame, the paddle is at the bottom left corner of the screen. Based on these frames, I

will move the paddle to the bottom right corner of the screen in the next frame.

Resp. 2, LLaVA's hallucinated response

Fig. 7, A group of frames of Pong gameplay

Based on the three frames provided, I will move the paddle up to hit the ball.

Resp. 3, LLaVA's response, missing sufficient reasoning

Discussion

My work presents a proof-of-concept application of the LLaVA model to the Pong task. The experiment results demonstrate that LLaVA has the capabilities to take in visual input such as those from frames of Pong gameplay and correctly determine as well as provide reasoning for future actions.

However, my experiment is not without its limitations. Firstly, compute times of around a minute for each inference would not be possible for live Pong gameplay. That being said, this could be mitigated through sufficient fine-tuning on Pong gameplay and more powerful hardware than a single local machine. Furthermore, while my results do show that LLaVA has the capability to provide correct actions for Pong, these results are by no means conclusive nor comprehensive. It’s responses were somewhat erratic despite producing correct actions on the majority of inputs, with incorrect reasonings and occasional hallucinations.

I do believe, however, that my results and experimentation represent a meaningful work in demonstrating a downstream application for LLaVA that could be further explored. LMMs will continue to improve and their applications will continue to broaden. Making complex decisions and actions in video games in live time could be a reasonable future step for LMMs and LLaVA family models in particular. As further extrapolation, LMMs that are able to make complex real-time decisions like those in video games could additionally be applied to other complex decision making tasks or towards powerful generalist agents.

Conclusion

I present Pong on Fire, an application of LLaVA for the Pong game task. I successfully create an environment to generate frames of Pong gameplay and load a LLaVA model to generate actions in response to these frames. Through my experimentation, I’m able to demonstrate a first step towards an LMM-based gaming agent capable of reasoning through actions in games like Pong.

Future Work

Future work could focus on more directly fine-tuning LLaVA for the Pong tasks or other Atari games, OpenAI baseliness, or Gymnasium environments. Fine-tuning for the action space in these environments should drastically improve upon the model’s success and reasoning. The prompt structure that I use could also be improved, but fine-tuning will likely make a greater difference.

Additionally, advancements in chain-of-thought reasoning could further be applied to LMM-based approaches to developing gaming agents. This additional reasoning could provide greater accuracy, but would lead to slower compute time.

Regardless of method, future models in this space should be evaluated not only on their ability to generate correct actions but also their ability to explain why. As I demonstrated, although LLaVA was correct more often than not, it did not always provide a sensible reasoning.

Overall, I see my work as a meaningful first step towards applying LMMs towards video games. Future work should be able to expand significantly on the capabilities and performance of models, while also encouraging more intelligent reasoning.

Links

References

[1] Liu, H., Li, C., Wu, Q., & Lee, Y. J. (2023). Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv [cs.CV]. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.08485

[2] Niu, D., Sharma, Y., Biamby, G., Quenum, J., Bai, Y., Shi, B., … & Herzig, R. (2024). LLARVA: Vision-Action Instruction Tuning Enhances Robot Learning. arXiv [cs.RO] Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.11815

[3] Liu, H., Li, C., Li, Y., & Lee, Y. J. (2024). Improved Baselines with Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv [cs.CV]. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.03744

[4] Zhai, S., Bai, H., Lin, Z., Pan, J., Tong, P., Zhou, Y., … & Levine, S. (2024). Fine-Tuning Large Vision-Language Models as Decision-Making Agents via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv [cs.AI] Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.10292

[5] M. G. Bellemare, Y. Naddaf, J. Veness and M. Bowling. The Arcade Learning Environment: An Evaluation Platform for General Agents, Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, Volume 47, pages 253-279, 2013. https://github.com/Farama-Foundation/Arcade-Learning-Environment