Neural Game Engine

This report explores recent advances in neural game engines, with a focus on generative models that simulate interactive game environments. Based on the prior presentation of GameNGen, a diffusion-based video model trained on DOOM, I review and compare several state-of-the-art approaches including DIAMOND, MineWorld, IRIS, GameGAN, and the original World Models. I also analyze their differences in architecture, visual fidelity, speed, and controllability, highlighting the trade-offs each design makes. Finally I conclude with a discussion on future directions for building responsive, efficient, and generalizable neural simulators for reinforcement learning and interactive media.

Introduction

In the earlier presentation, we have explored the GameNGen together, a neural game engine built using a diffusion-based video model. The goal of GameNGen is to generate realistic gameplay sequences from pixel inputs, simulating game environments without relying on traditional physics or rule-based engines. One of the key ideas was to use a powerful video diffusion model that could produce rich and coherent game visuals, allowing agents to interact with imagined worlds in a way that looks visually convincing.

Before these recent advances, earlier models like World Models, GameGAN, and IRIS laid the foundation by either simulating in compact latent spaces or using GANs and transformers for visual prediction. However, they struggled with long-term consistency, visual detail, or speed—motivating the newer generation of neural game engines I focus on in this report.

While GameNGen showed promising results, especially in terms of visual quality, it also brought up some important limitations. For example, it struggled with speed due to the heavy diffusion process (achieved approximately 20 FPS), and had trouble maintaining long-term consistency in gameplay. These issues sparked a lot of interest in the community, and several newer models have tried to tackle these challenges from different angles.

One of these new attempts is DIAMOND, which also uses diffusion for world modeling. But this model focuses more on action-conditioning and control. It shows that adding extra loss terms and guiding the model through better conditioning can help it generate more meaningful sequences, not just pretty. DIAMOND also runs experiments in classic environments like Atari games and demonstrates measurable improvements in decision-making performance, thanks to the improved visual details.

Besides, MineWorld goes in a different direction. Instead of diffusion, it uses an autoregressive transformer model to simulate future frames. In the Q&A part of my presentation, we discussed the diffculties for extending GameNGen to AAA games like Minecarft or Apex. Suprisingly, MineWorld has achieved this goal. Compared with DOOM for GameNGen, Mineworld simulates in Minecraft, which is much more complex. It takes both visual frames and player actions, turns them into discrete tokens, and feeds them into a transformer that predicts what happens next. Based on a parallel decoding strategy, MineWorld can generate multiple frames per second, which makes it much more usable for real-time interactions.

All these models — GameNGen, DIAMOND, MineWorld — are part of a growing trend where generative models are being used not just to produce content, but to simulate interactive environments. This shift has major implications for reinforcement learning, robotics, and even game development. In this report, I will explore how these models differ in terms of architecture, speed, visual quality, and controllability.

Prior Works

The idea of learning a model to simulate environments, also known as world modeling, has been explored for years in reinforcement learning and generative modeling. Early work like Ha and Schmidhuber’s World Models (2018) introduced a framework that combined a variational autoencoder (VAE), a recurrent world model, and a controller, allowing agents to learn entirely within their own imagination. While this approach was conceptually powerful, it relied heavily on low-dimensional latent states, which means that much of the visual richness and contextual information was lost during compression. Later efforts such as IRIS (2022) built on this by introducing discrete latents via vector quantization and modeling sequences with Transformers, achieving strong results on Atari with limited data. However, these models still suffered from the trade-off between visual fidelity and computational efficiency, often missing important details like small sprites or dynamic elements critical to gameplay decisions.

Personally I would say that the introduction of GameGAN (2020) could be a milestone, which used a GAN-based approach to learn how to simulate entire environments directly from visual observations and player actions. While impressive for its time, GameGAN still lacked generalization capabilities and tended to fail on relatively long horizon rollouts or 3D environments. That’s where GameNGen entered the scene. Instead of compressing the environment into a minimal latent space or relying on GANs, GameNGen employed diffusion models, which was originally designed for high-quality image synthesis, to generate video game frames in an autoregressive fashion. By training on gameplay data from DOOM and leveraging a modified Stable Diffusion model, GameNGen could generate realistic, temporally coherent frames based on previous context and action inputs. It introduced several techniques to stabilize the generation process, including noise augmentation during training and decoder fine-tuning for UI elements. The result was a neural “game engine” capable of producing video sequences at a surprisingly high quality, even reaching up to 20 FPS on a TPU. However, its main limitations were relatively high computational costs and limited memory, which affected both real-time interaction and long-horizon consistency.

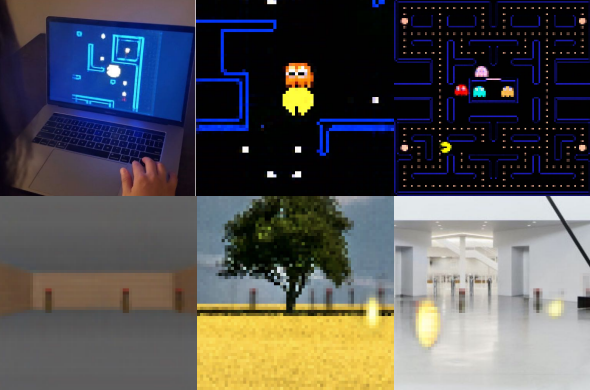

Figure 1. GameGAN: If you look at the person on the top-left picture, you might think she is playing Pacman of Toru Iwatani, but she is not! She is actually playing with a GAN generated version of Pacman. In this paper, GameGAN was introduced that learns to reproduce games by just observing lots of playing rounds. Moreover, the model can disentangle background from dynamic objects, allowing us to create new games by swapping components as shown in the center and right images of the bottom row.

Building on the foundation laid by GameNGen, newer models such as DIAMOND (2024) extended the idea of diffusion-based world modeling while directly addressing some of these limitations. DIAMOND uses a more optimized sampling process based on the Elucidated Diffusion Models (also called “EDM”) framework, which reduces the number of denoising steps needed for generating a frame. This leads to significant speedups without sacrificing visual fidelity. More importantly, DIAMOND emphasized the importance of preserving visual detail for reinforcement learning agents: even small improvements in pixel accuracy translated to better decision-making in agents trained purely in simulation. It also introduced an action-conditioned training setup that enabled better controllability, allowing the model to generate scenes that actually respond to input actions. DIAMOND outperformed all previous approaches on the Atari 100K benchmark and even demonstrated impressive results on a real-world FPS game (CS:GO), showing that diffusion-based world models could scale beyond 2D arcade games. Together, these works reflect a major evolution in learned simulators—from basic frame predictors to highly detailed, interactive neural environments that blur the line between video generation and game engine functionality.

Figure 2. Images captured from people playing with keyboard and mouse inside DIAMOND’s diffusion world model. This model was trained on 87 hours of static Counter-Strike: Global Offensive (CS:GO) gameplay (Pearce and Zhu, 2022) to produce an interactive neural game engine for the popular in-game map, Dust II. Best viewed as videos at https://diamond-wm.github.io.

Comparison

Methodology

Since this report focuses on a literature-based review without running code or experiments, the comparison of models is conducted through a conceptual and technical analysis of their published papers, reported results, and architectural designs. Specifically, I analyze each model across the following key dimensions:

- Architecture: The type of model used (e.g., VAE-RNN, GAN, Transformer, Diffusion) and its general structure.

- Visual Quality: The realism and coherence of the generated frames, often judged via FVD scores, human evaluation, or qualitative inspection.

- Speed and Efficiency: The reported or estimated inference speed, often measured in FPS or number of frames generated per second.

- Controllability: How well the model responds to agent actions and whether it supports meaningful interaction.

- Generalization: The model’s ability to work across varied game environments or settings, beyond the specific domains it was trained on.

- Use Case Fit: Whether the model is better suited for reinforcement learning simulation, visual imitation, real-time play, or offline rollout.

I rely on each paper’s empirical results, qualitative demos, and architectural insights to draw these comparisons, aiming for a high-level yet grounded evaluation of where each model stands.

Comparison Table

| Model | Architecture | Visual Quality | Speed / FPS | Controllability | Generalization | Use Case Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Models [1] | VAE + RNN + Controller | Low (latent-only) | Fast | Weak (abstract input) | Low (simple tasks) | Latent planning, early imagination |

| GameGAN [2] | GAN-based video model | Moderate (GAN artifacts) | Medium | Weak–Moderate | Moderate (2D games) | Visual imitation, offline simulation |

| IRIS [3] | VQ-VAE + Transformer | Moderate (token-based) | Fast | Moderate | Moderate (Atari) | Efficient Atari world modeling |

| GameNGen [4] | Diffusion (video) | High (DOOM-level detail) | Slow (~20 FPS) | Weak–Moderate | Limited (mostly DOOM) | High-fidelity simulation |

| DIAMOND [5] | Diffusion + EDM | High (Atari + CS:GO) | Medium–Slow | Strong (action-guided) | High (2D + 3D) | RL rollout, controllable simulation |

| MineWorld [6] | Tokenized Transformer | Moderate–Good (MCraft) | Fast | Strong | High (open-world envs) | Real-time interaction, Minecraft AI |

Advantages and Disadvantages

World Models (Ha & Schmidhuber, 2018) introduced a foundational framework that combined a variational autoencoder (VAE), a recurrent world model (RNN), and a simple controller to allow agents to learn entirely within a compressed simulation. The biggest strength of this approach was its simplicity and efficiency—it could represent complex visual environments like car racing in a compact latent space, enabling fast simulation and lightweight training. However, the trade-off was a loss in visual fidelity. Because the model learned to represent only abstract latent features rather than full-resolution frames, it often missed small but important visual cues. This made it less suitable for tasks where detailed spatial information or pixel-level feedback was crucial.

GameGAN (Kim et al., 2020) took a different approach by directly learning to generate game frames using GANs, conditioned on previous frames and player actions. This allowed the model to learn game mechanics visually, without being explicitly programmed. It was a breakthrough in terms of realism for simple arcade-style games like Pac-Man. The major advantage was its end-to-end frame generation, which made it more intuitive and visual than latent-based approaches. However, GameGAN faced several limitations. It struggled to generalize to more complex or 3D environments, produced visual artifacts under longer rollouts, and often failed to capture longer-term game dynamics, making it unreliable for extended agent interaction.

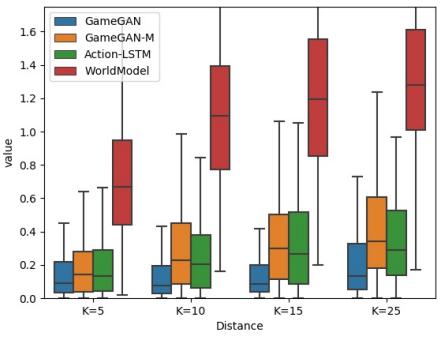

Figure 3. Comparison from GameGAN: Box plot for Come-back-home metric. Lower is better. As a reference, a pair of randomly selected frames from the same episode gives a score of 1.17 ± 0.56.

IRIS (2022) improved upon earlier world modeling efforts by combining discrete latent tokenization (via VQ-VAE) with an autoregressive Transformer architecture to predict future observations. This method proved to be very sample-efficient, achieving strong performance on Atari with limited training data. Its key strengths were in planning and sequence modeling—the Transformer could reason over long horizons better than RNNs, and the tokenized representations kept the input compact and manageable. Still, IRIS inherited a core limitation from its discretization step: subtle visual details often got lost or blurred, which could affect tasks where pixel accuracy matters, such as tracking small objects or UI elements in games.

GameNGen (2024) represented a leap forward by introducing diffusion models into the world modeling space. Unlike earlier models that worked with compressed latent spaces or low-res visuals, GameNGen was trained to directly generate high-resolution game frames (from DOOM) using a video diffusion pipeline. This gave it a huge boost in visual quality—even human observers had difficulty distinguishing generated frames from real gameplay. It also incorporated techniques like noise-augmented training to improve rollouts and added decoder fine-tuning for in-game UI clarity. However, diffusion models are notoriously slow, and GameNGen was no exception. Despite achieving ~20 FPS on a TPU, its computational demands make it impractical for lightweight or real-time settings. It also lacked a robust memory mechanism, which sometimes caused inconsistencies over longer sequences.

DIAMOND (2024) followed GameNGen but aimed to make diffusion-based simulation more practical and controllable. By switching to EDM (Elucidated Diffusion Models), DIAMOND significantly reduced the number of denoising steps needed during frame generation, speeding up inference while maintaining high visual quality. It also emphasized the importance of preserving visual details for reinforcement learning, showing that better visuals could directly translate into better policy learning. DIAMOND incorporated action-conditioning more explicitly, making its predictions more responsive and meaningful. It achieved top performance on Atari benchmarks and even scaled to more complex environments like CS:GO. However, it still required substantial computational resources, and its real-time interactivity—while improved—was not yet on par with faster autoregressive models.

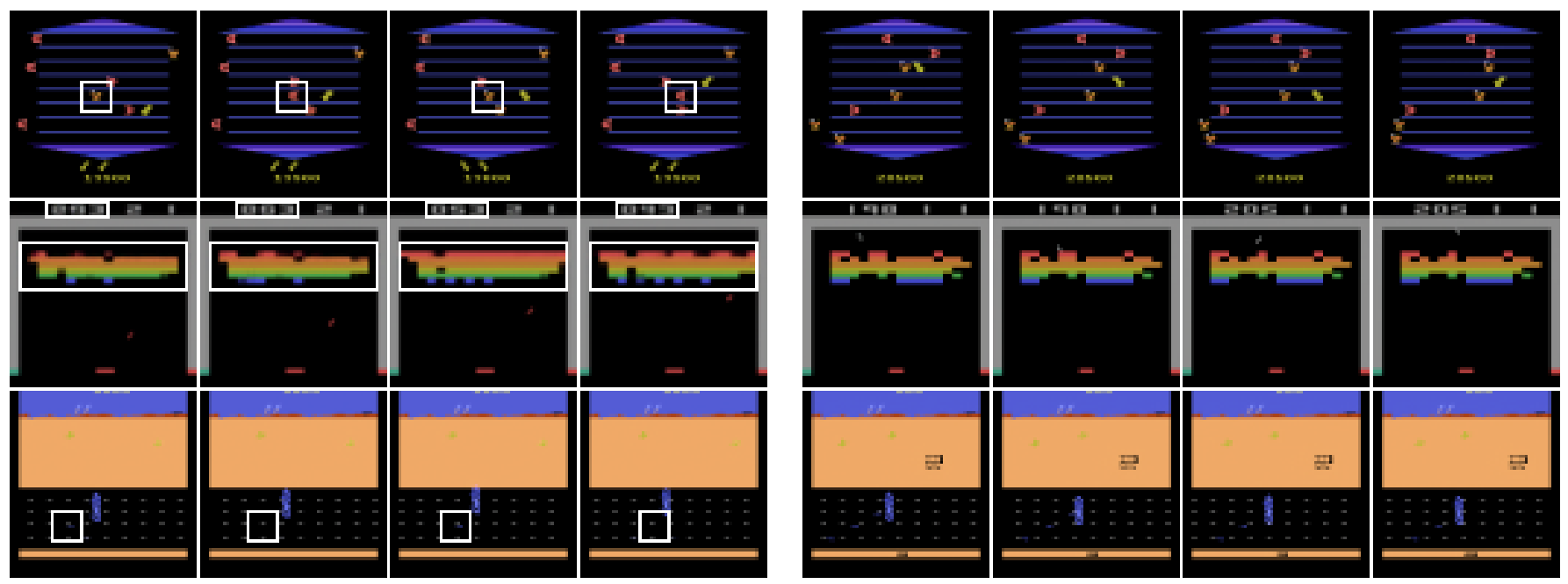

Figure 4. Consecutive frames imagined with IRIS (left) and DIAMOND (right). The white boxes highlight inconsistencies between frames, which we see only arise in trajectories generated with IRIS. In Asterix (top row), an enemy (orange) becomes a reward (red) in the second frame, before reverting to an enemy in the third, and again to a reward in the fourth. In Breakout (middle row), the bricks and score are inconsistent between frames. In Road Runner (bottom row), the rewards (small blue dots on the road) are inconsistently rendered between frames. None of these inconsistencies occur with DIAMOND. In Breakout, the score is even reliably updated by +7 when a red brick is broken.

MineWorld (2025) tackled the problem from the opposite direction. Instead of focusing on high-fidelity image generation, it aimed for real-time, controllable simulation using an autoregressive Transformer trained on Minecraft gameplay. By tokenizing both visual and action data, MineWorld created a compact representation that could be processed quickly in parallel, achieving interactive speeds of several frames per second. This made it ideal for real-time agent interaction, especially in open-ended environments like Minecraft. The model was also open-source and included useful metrics to evaluate controllability and action alignment. However, its visual output was less detailed than diffusion models, and the heavy reliance on Minecraft-specific discretization raised questions about generalization to other environments or tasks with more complex visuals.

Discussion

Looking across the models I have reviewed, including World Models, GameGAN, IRIS, GameNGen, DIAMOND, and MineWorld, a few key patterns and trade-offs may be emerged. One of the most important is the balance between visual fidelity and computational efficiency. Models like GameNGen and DIAMOND prioritize generating highly detailed and realistic frames using diffusion processes. This level of realism is important for agent decision-making in environments where small visual cues can change outcomes, such as spotting an enemy or a power-up. However, these benefits come at a cost. Diffusion-based models require iterative sampling, which slows down generation significantly. Even with optimization tricks like the ones DIAMOND uses, they still lag behind autoregressive models in terms of speed and usability for real-time interaction.

On the other side of the trade-off are models like IRIS and MineWorld. These transformer-based architectures tokenize input data and process it sequentially or in parallel, allowing for much faster inference. Specifically, MineWorld is designed with real-time interaction in mind, decoding multiple spatial tokens in parallel to reach playable frame rates. This makes it far more suitable for live environments, such as interactive simulations or multi-agent games. However, the drawback is that these tokenized models often lack the richness of full-frame diffusion outputs. They abstract away some details at the level of pixel, which might be acceptable for planning but could be a limitation in tasks requiring high visual precision.

Another dimension of comparison is controllability—how well a model can respond to specific player or agent actions. GameGAN and early latent-based models tended to blur this relationship, generating plausible but sometimes unrelated frames. In contrast, DIAMOND and MineWorld both place a strong emphasis on action-conditioning, ensuring that generated outcomes align more closely with inputs. This is especially important for reinforcement learning or agent-based tasks where the quality of feedback directly affects learning. Action-aware training objectives, like the ones used in DIAMOND, have proven to significantly improve this aspect.

I also noticed differences in how well these models generalize to more complex or diverse environments. Earlier models were usually tested on simple settings like Atari or 2D arcade games. GameNGen moved to DOOM, a more dynamic and visually rich environment, while MineWorld tackled the challenge of Minecraft, which is both open-ended and visually complex. This progression reflects growing confidence in these architectures, but also highlights how scaling up introduces new challenges—especially around long-term memory, scene coherence, and temporal consistency.

Overall, there’s no single model that “wins” in every category. Each represents a different point along the spectrum of speed, quality, and control. For applications like agent training in offline simulators, slower but richer models like DIAMOND may be more useful. For interactive settings or games, MineWorld’s transformer-based design is a better fit. These trade-offs are likely to remain central as the field continues to explore what the ideal neural game engine should look like.

Conclusion and Future Work

In this report, I examined the evolution of learned world models and neural game engines, starting from early latent-based simulators like World Models and IRIS, to more visually sophisticated generators like GameNGen and DIAMOND, and finally to real-time transformer-based systems like MineWorld. Each model reflects a different design philosophy and set of trade-offs between visual quality, generation speed, controllability, and generalization. GameNGen and DIAMOND showed how diffusion models can deliver high-fidelity visuals and boost agent performance, but they remain limited by their computational demands and relatively slow inference. On the other hand, models like MineWorld prioritize usability and speed, making them more practical for interactive or online applications, even if they compromise on pixel-level detail.

Across all these models, one theme stands out: the growing ambition to build neural simulators that are not just generative, but interactive, responsive, and reliable. Whether the goal is to train reinforcement learning agents, generate synthetic training data, or build immersive game environments, the requirements go far beyond simple frame prediction. We now need models that can reason over time, respond meaningfully to input actions, and scale to diverse, dynamic worlds. While current architectures have taken big steps in this direction, challenges like long-term memory, cross-domain generalization, and efficient conditioning still remain open problems.

Looking ahead, promising directions include hybrid models that combine the realism of diffusion with the speed of token-based transformers, memory-augmented agents that can retain state over long episodes, and modular systems that separate world dynamics from rendering or control. Another key area is improving action controllability without sacrificing sample efficiency—potentially using auxiliary objectives, disentangled representations, or contrastive methods. As this field matures, we expect the boundary between learned models and traditional engines to blur even further, opening up exciting opportunities not just in AI, but in game design, robotics, and interactive media more broadly.

References

[1] D. Ha and J. Schmidhuber, World Models, arXiv:1803.10122, 2018. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.10122

[2] S. Kim, Y. Choi, J. Yu, J. Kim, J. Ha, and B. Zhang, Learning to Simulate Dynamic Environments with GameGAN, arXiv:2005.12126, 2020. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2005.12126

[3] V. Micheli, E. Grefenstette, and S. Racanière, Transformers are Sample-Efficient World Models, arXiv:2209.00588, 2022. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2209.00588

[4] Y. Valevski, O. Sharir, A. Gordon, M. Tal, A. Bar, A. Azaria, N. Shenfeld, Y. Meshulam, J. Berant, and S. Shalev, Diffusion Models Are Real-Time Game Engines, arXiv:2408.14837, 2024. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2408.14837

[5] M. Alonso, A. Ramesh, Y. B. Kim, M. G. Azar, M. Janner, P. Agrawal, Y. Chebotar, and Y. Tassa, Diffusion for World Modeling: Visual Details Matter in Atari, arXiv:2405.12399, 2024. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.12399

[6] J. Fang, Y. Wang, W. Shao, Y. Zhao, Z. Wang, M. Yang, W. Zhan, B. Dai, H. Shi, C. Liu, B. Zhou, and J. Wang, MineWorld: A Real-Time and Open-Source Interactive World Model on Minecraft, arXiv:2505.14357, 2025. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14357