A Survey of LERF-TOGO and Related Works

In this article, we examine LERF-TOGO, a zero-shot task-oriented grasper, meaning it can grasp unseen objects at the correct part depending on what its task is. We first conduct an overview of two previous state of the art approaches. Then, we discuss the various foundation models that were used to construct the LERF-TOGO pipeline. Afterwards, we assess the advantages and limitations of LERF-TOGO. Finally, we briefly discuss trends that can be seen throughout the years of research efforts in task-oriented grasping - namely, the increasing prominence of advanced foundation models in the development of novel task-oriented grasping models.

- Introduction

- Task-oriented Grasping with Semantic and Geometric Scene Understanding (Detry, et al., 2017)

- Same Object, Different Grasps: Data and Semantic Knowledge for Task-Oriented Grasping (Murali, et al., 2020)

- Preliminaries to LERF-TOGO

- Language Embedded Radiance Fields for Zero-Shot Task-Oriented Grasping (Rashid, et al., 2023)

- Comparison Across Time

- References

Introduction

Imagine that in the distant future, you ask your helper robot to fetch you the flowers from the evening before. You’re excited to examine this gift from your loved one and reminisce about them. As your robot turns the corner, you’re aghast to find your robot grasped the flowers by the bud, crushing them in the process! Your robot cheerily reports, “Task completed!”

Clearly, this is not how we want our robots to behave. It is already a challenge to train our robots to identify and grab objects at all. However, accomplishing even this feat is not sufficient for deployment, as demonstrated by the scenario above. Although the story was fictitious, it is more realistic than we may think. Therefore, there is a need for improvements in task-oriented grasping. Let’s start by surveying the development of task-oriented grasping models from the past few years.

Task-oriented Grasping with Semantic and Geometric Scene Understanding (Detry, et al., 2017)

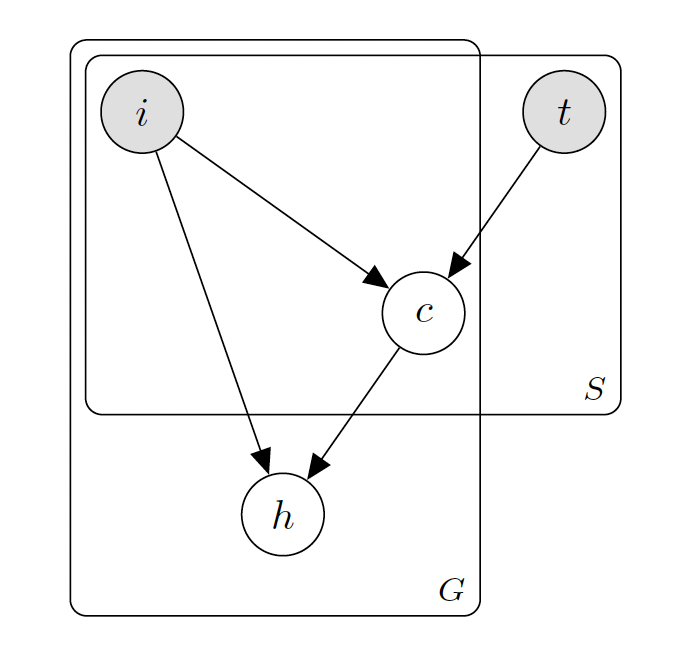

This paper takes a more classical and mathematical approach in formulating the model for task object grasping. Below is a schematic of the model:

Schematic of Detry el al.’s task oriented grasper model (Detry, et al.)

The model is composed of two parts: the semantic model and the geometric model.

The semantic model receives a task input from the user (t) and “sees” the scene using a depth sensor (i). It then checks if there are any parts of the scene that might be suitable for the task that the user specified.

How does the model do this? Well, computers can take the inputs it receives (which are in the form of many numbers) and perform math (usually matrix multiplications and simple element-wise activation functions) to get a useful output. We call a system that does this a “neural network” due to their neurological inspiration. CNNs (convolutional neural networks) are neural networks that are particularly good at looking at an image and aggregating information from regions that are physically close to each other. This makes them a popular choice for tasks like looking at an image and deciding what category it belongs to (image classification).

The semantic model uses CNNs to determine what object parts in the image would be good to grasp to achieve a given task. The semantic model has four CNNs for each of the available tasks: transport, handover, pour, and open.

The geometric model then takes in the graspable object parts (c) from the semantic model and determines the best strategy for grasping this shape. It does this by maintaining a dictionary of object shapes and the instructions for the robot arm to grasp that shape. It then feeds in these instructions to the robot for execution.

This model is impressive for its modularity and performance, especially for the time. Its success rate for grasping objects was 88% for single-object scenes and 82% for multi-object scenes. One can appreciate its mathematical rigor, which is not often found in today’s papers.

However, the limitations are evident. For one, the semantic model can only process one of the four tasks that it has trained for. Although the four task categories are general enough such that the model can perform a variety of grasps, its is inconvenient to have to give your instruction in terms of the four tasks (eg: we couldn’t say “give me the bag of chips” but rather need to say “handover the bag of chips.”). Moreover, the model will not understand novel categories of tasks such as “cut the dough in half” (the task here being “cut”). A similar limitation exists in the geometry model; the model only knows how to grasp previously seen shapes. The paper specifically notes that the model has trouble generalizing to unseen geometries.

Same Object, Different Grasps: Data and Semantic Knowledge for Task-Oriented Grasping (Murali, et al., 2020)

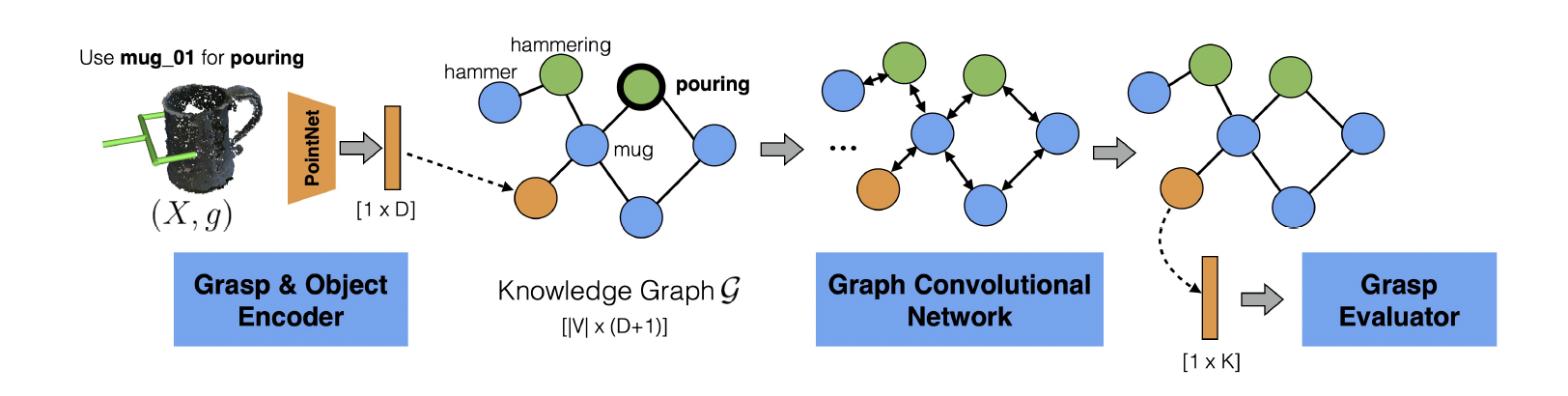

Outline of Murali, et al.’s architecture (Murali, et al.)

Murali, et al. formulate the observations and task as a graph and use a graph convolutional network (GCN) to determine the best grasp. The model starts off with a knowledge graph (G) that represents the relationships between related objects and tasks. The model then inputs this graph to a GCN, which is a type of a graph neural network (GNN).

GNNs are neural networks whose inputs are graphs. The graphs are represented by two matrices: (1) a feature matrix where each row encodes features of each node, and (2) an adjacency matrix that encodes which nodes are connected to each other. A GCN is a type of GNN which is designed so that adjacent nodes can communicate to each other and impact its feature values.

As seen in the figure above, an encoding of the object is produced using a pretrained neural network and added to this knowledge graph. Then, the GCN is run for some number of iterations, allowing adjacent nodes to communicate with each other. Note that among the nodes in the graph are also task nodes, and as the model trains, it will learn what it grasped to successfully accomplish that task.

We can see improvements over the model that Detry el al. presented three years prior. Interestingly, the GCN does not need the user to specify what the task is; it only needs to know what to grasp. It can infer how to best grasp this object from its experience of having grasped similar objects. However, this feature could also be an impediment, as a single object may be used for different tasks and grasped differently for each of them (eg: a pair of glasses for wearing vs. wiping the lenses).

Preliminaries to LERF-TOGO

We now arrive at the discussion of the main model of this article: LERF-TOGO. LERF-TOGO uses many foundation models to achieve its high performance. Foundation models are models that were trained with lots of data and time, which is usually much too expensive for most people and organizations to do. These advanced models can then be repurposed (and potentially fine-tuned) for new tasks, forming the foundation of these new models.

LERF-TOGO uses many foundation models: NeRF (Mildenhall, et al.), CLIP (Radford, et al.), and DINO (Caron, et al.). We will briefly look at each of these models.

NeRF: Neural Radiance Fields

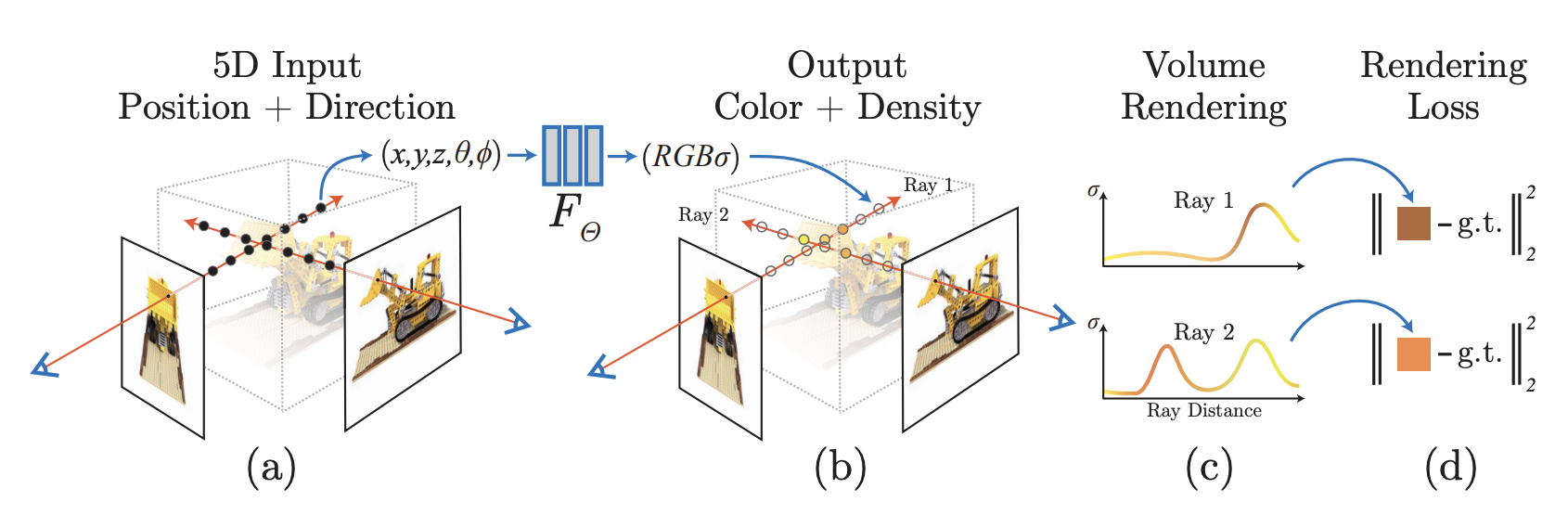

Schematic for NeRF (Mildenhall, et al.)

NeRF takes a field of 2D pictures (and the camera’s position) of a single scene and generates a 3D reconstruction of the scene. It then compares the actual 2D images with the view of the 3D reconstruction from the same camera position and compares these two images. The difference between these two images helps NeRF tweak itself to get an even more accurate reconstruction. Because the entire process of synthesizing a new view is differentiable, NeRF can train directly from the image differences (rather than using a proxy measure that might be imprecise).

Many thoughtful design details help NeRF achieve greater photorealism at various camera positions. NeRF outputs the RGB values and the density of each position. The density is akin to opacity, meaning objects can allow colors behind them to partially pass through. Moreover, the color is modeled as a 256 dimensional feature vector that is combined with the camera angle to determine its color. This means the same point can look different depending on from where we are viewing it, which is true of objects we observe in real life, especially specular ones.

CLIP: Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training

CLIP embeds images and language to the same latent space, meaning the semantic meaning of these can easily be compared to each other despite their differing modality. CLIP learns how to do this through a contrastive learning objective, where the model tries to encode related inputs similarly and unrelated inputs differently. All the model needs to train are pairs of words and images which are related to each other, which is relatively easy to scrape from the internet. OpenAI has spent significant resources to scrape such data and train the model, making it a valuable foundation model for robustly embedding images and language.

One use case for CLIP is to look at an image and determine how similar it is to a given word. We could also partition the image to many parts and run the similarity comparisons for each part. This would help us see which part of the image is most similar to the given word. We will further explore this approach in our discussion about LERF.

DINO: Self-distillation with No Labels

DINO is the result of distilling self-supervised vision transformers. An emergent property is that DINO is very good at object segmentation. Specifically, self-attention heads at the last layer of the distilled model outlines the boundary of objects in response to the [CLS] token, a global representation of the image. Needless to say, DINO is a foundation model for object segmentation.

Examples of last layer self attention maps that show emergent object segmentation properties (Caron, et al.).

LERF: Language Embedded Radiance Fields (Kerr, et al.)

LERF combines the models above to embed language into 3D scenes. We briefly describe how all the components work together:

- NeRF generates the 3D reconstruction: NeRF takes in RBG images taken from different angles which form a hemisphere. It then generates a realistic 3D reconstruction.

- However, a key realization is that we’re not restricted to inputting just RBG images into NeRF. We could very well input other information about the 2D scene for NeRF to reconstruct into 3D.

- So, we compute the CLIP embeddings of different partitions of each 2D view. We add these to the RGB inputs so that NeRF is now receiving RGB+CLIP as its input. When NeRF learns to recreate 3D reconstructions, it’ll learn to incorporate CLIP embeddings into the 3D space as well. We call this “3D CLIP embeddings”.

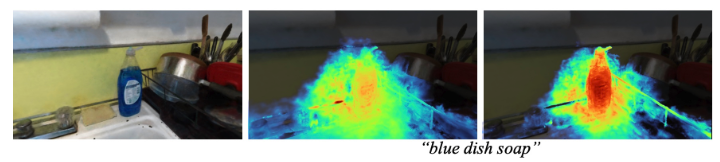

It now appears that we are ready to query our reconstruction with natural language. However, the model at this point doesn’t have a good idea of where objects start and end, so it’ll give a smudged and patchy output (see middle frame of the figure below).

Frames showing (left) a 2D RGB view of a scene, (middle) relevancy field for “blue dish soap” without DINO regularization, (right) relevancy field with DINO regularization (Kerr, et al.).

Fortunately, we have yet another foundation model that’s good at solving precisely this issue of object segmentation:

- Much like how we added CLIP embeddings, we can give each 2D view to DINO and ask it to segment objects. This gives us DINO embeddings for each point of the 2D view. We can then give this information to NeRF, and NeRF will include it in its reconstruction (much like what it did for CLIP). As the model learns both the CLIP and DINO embeddings at the same time, it helps the CLIP embeddings follow the object boundaries given by the DINO embeddings.

Now, our relevancy fields are bound much better to the pertinent objects! This 3D reconstruction with language embeddings give us a useful backbone for our final task-oriented grasper:

Language Embedded Radiance Fields for Zero-Shot Task-Oriented Grasping (Rashid, et al., 2023)

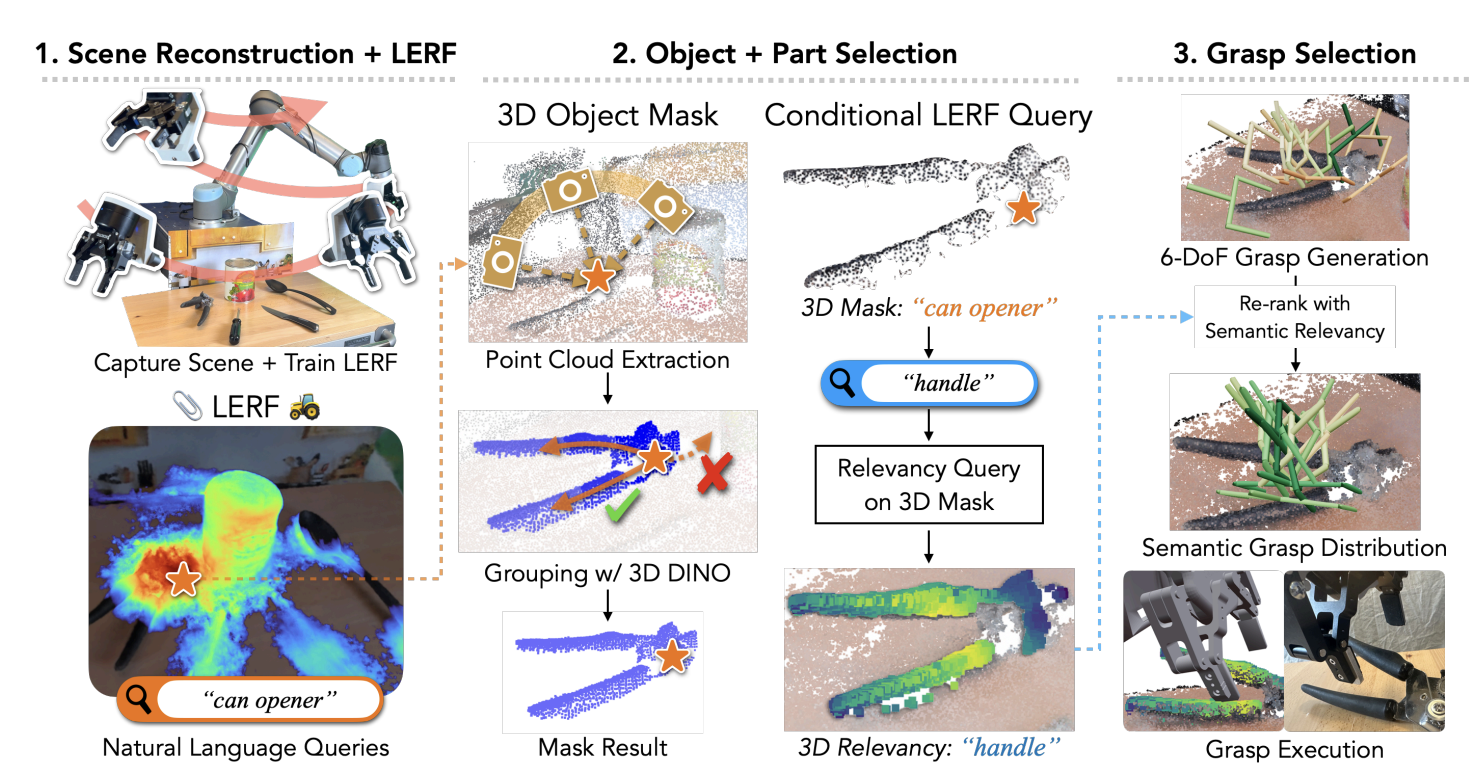

Schematic overview of LERF-TOGO (Rashid, et al.).

We now arrive at a point where we train our robot to avoid disastrous scenarios like the one in the beginning of this article!

First, let’s consider the queries that are given to LERF-TOGO. LERF-TOGO needs to know what the object it is trying to grab as well as what part it should grab it by. In the example above, the object is “can opener” and the part is “handle”. When a user gives a natural language prompt (eg: “scrub the dishes”), LERF-TOGO employs a prompt-constrained LLM to decide what the object and part are (eg: “dish brush; handle”).

With this preprocessing in mind, we examine how the LERF-TOGO pipeline is constructed. LERF-TOGO first starts by taking the hemisphere of pictures to train a LERF of the scene. Now, we can query our object (eg: “can opener”) in the LERF to get a relevancy field. If we perform a weighted average of the relevancy field, we can get a single point that is the center of that object.

From this center, we can find all the adjacent points that have a similar DINO embedding. At a high level, this means we’re finding the entire object that the center point belongs to. Once we have this mask, we can now query the part (eg: “handle”) on just the object. In our example, this means that we’ll only look at the handle that is a part of the can opener; we’ll ignore the handles of different objects (like a saucepan) that might be present in a different part of the scene. The result of this process is a relevancy field that highlights where we should grasp our object by.

We then get an off the shelf grasp generation network that gives us potential grasps from looking at just the object geometry. We then take these possible grasps and rerank them by whether the proposed grasps would hold the regions highlighted by our relevancy field. We then take the best of the reranked grasps and execute it.

Advantages of LERF-TOGO

LERF-TOGO enjoys the advancements made by its foundation models which have seen explosive growth in the past few years. For instance, we recall that the work by Detry, et al. (2017) gave the user only four options for instructing the robot on which task to perform. Due to the advanced language abilities of the GPT LLM used in LERF-TOGO, users can provide the model with essentially an arbitrarily formatted natural language instruction, and GPT will distill the semantic information into a format that is compatible with the model. Moreover, rather than relying on prototypical geometries to determine how to grasp for a given task, LERF-TOGO discerns what part of the specified object is most suitable for the task. All in all, LERF-TOGO has much better semantic reasoning abilities thanks to the GPT foundation model, resulting in a more intuitive user experience.

There is also the advantage that, thanks to the pretraining done on CLIP and DINO, only the LERF (which is essentially just a 3D reconstruction) needs to be trained. Capturing the semantic meaning of objects throughout the scene is well-executed by these foundation models.

Limitations of LERF-TOGO

Perhaps the most glaring difficulty of LERF-TOGO is that it must perform a LERF reconstruction for each new scene. The process of capturing the entire hemisphere of views and training the LERF model to reconstruct the scene takes a few minutes, making it highly cumbersome for real world use and impossible to incorporate into real-time pipelines. It also presumes that the scene has enough free space surrounding it such that the robot could perform the hemispheric sweep, which would not hold in settings such as a stovetop with a wall behind it.

Moreover, the LERF reconstruction is not updated after a task is completed. Thus, if we move an object to a different location, the model does not update its LERF to match that. Therefore, if the robot tried to grab an object that has moved since the last scan, it would foolishly grasp where the object formerly was.

Furthermore, generating the semantic relevancy field can be a finicky process. For one, CLIP can be highly sensitive to minor variations in phrasing, resulting in varying grasp locations that might not match human preference. This difficulty is especially pronounced when an LLM infers the object-part pair. LLM-provided parts result in an 11% decrease in correct part grasp accuracy compared to when a human supplies the part. Even when a human supplies the part, the part accuracy is 82%. Note that the paper by Detry, et al. from six years before achieved a correct part grasp accuracy score of 78~82%, although their testing environments and generalizabilities are different.

Comparison Across Time

Over time, developers have relied increasingly on pretrained “black box” foundation models to formulate their models. Examining the papers from 2017, 2020, and 2023 reveal this trend. Detry, et al. (2017) lay forth mathematical justification for their models, and their entire model is trained from scratch. In Murali, et al. (2020), some previous work (i.e. PointNet) is used to embed the object, but the main engine of their grasp generation (GCNGrasp) was original and trained from scratch.

Conversely, LERF-TOGO (Rashid, et al., 2023) is essentially a strategic concatenation of various pretrained foundation models, with the only parameter training done for scene reconstruction with LERF. Moreover, the explanation of each component is given almost exclusively at a qualitative level. This is not to diminish the intellectual contributions of Rashid, et al. but rather to observe a trend in the development of novel models. Indeed, it is precisely this trend that likely has inspired courses such as the one I am writing this article for (CS 269: Seminar on AI Agents and Foundation Models).

References

- M. Caron, H. Touvron, I. Misra, H. J´egou, J. Mairal, P. Bojanowski, and A. Joulin. Emerging properties in self-supervised vision transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pages 9650–9660, 2021.

- R. Detry, J. Papon, and L. Matthies. Task-oriented grasping with semantic and geometric scene understanding. In 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), pages 3266–3273. IEEE, 2017.

- J. Kerr, C. M. Kim, K. Goldberg, A. Kanazawa, and M. Tancik. Lerf: Language embedded radiance fields. ICCV, 2023.

- B. Mildenhall, P. P. Srinivasan, M. Tancik, J. T. Barron, R. Ramamoorthi, and R. Ng. NeRF: Representing scenes as neural radiance fields for view synthesis. In European Conference on Computer Vision, pages 405–421. Springer, 2020.

- A. Murali, W. Liu, K. Marino, S. Chernova, and A. Gupta. Same object, different grasps: Data and semantic knowledge for task-oriented grasping. In Conference on Robot Learning, 2020.

- A. Radford, J. W. Kim, C. Hallacy, A. Ramesh, G. Goh, S. Agarwal, G. Sastry, A. Askell, P. Mishkin, J. Clark, G. Krueger, and I. Sutskever. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision, 2021.

- A. Rashid, S. Sharma, C. M. Kim, J. Kerr, L. Y. Chen, A. Kanazawa, and K. Goldberg. Language embedded radiance fields for zero-shot task-oriented grasping. In Conference on Robot Learning, 2023.