Image Captioning with CLIP

Image captioning is a fundamental task in vision-language understanding, which aims to provide a meaningful and valid caption for a given input image in a natural language. Most existing image captioning model rely on pre-trained visual encoder. CLIP is a neural network which demonstrated a strong zero-shot capability on many vision tasks. In our project, we want to further investigate the effectiveness of CLIP models for image captioning.

- Introduction

- Related work

- Experiment

- Human in the Loop

- Methods

- Case Study

- Conclusion and Future Work

- Reference

Introduction

Image captioning is a fundamental task in vision-language understanding, which aims to provide a meaningful and valid caption for a given input image in a natural language. The general pipeline is composed of a visual encoder and a language model. Visual encoders should provide an effective representation of the visual content and the goal of language models is to predict the probability of a given sequence of words to occur in a sentence. Most existing methods rely on pre-trained visual encoders. From existing Vision and Language models and experiments, we observed that large-scale pre-training usually can lead to an improvement in generalization performance of the model. The recently proposed large-scale pre-trained neural network, CLIP[1], has demonstrated a strong zero-shot capability on many vision tasks. As a result, we propose to use CLIP’s image encoder as the visual encoder in the image captioning task to further investigate the effectiveness of CLIP pretrained encoder on extracting visual information.

In our project, we have experimented with two image captioning frameworks, CLIP-ViL[2] and ClipCap[3] which all use CLIP as visual encoder. From our experiment results, we showed that image captioning with CLIP visual encoder can outperform some of the state-of-art image captioning models which use object detection networks as visual encoders. The experiment results show that CLIP visual features can be as representative as the strong in-domain region-based features. We also develop a human in the loop image captioning model which can control the content of the captions by specifying start words.

Related work

CLIP

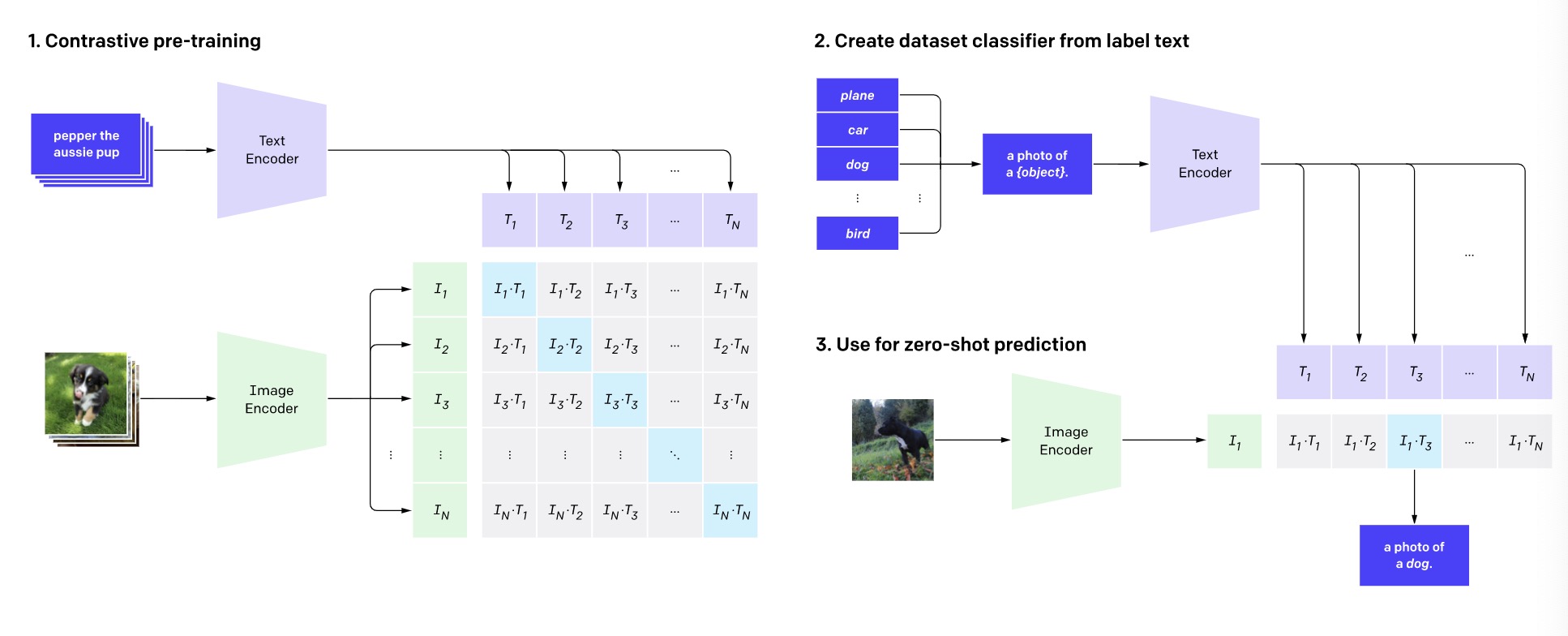

CLIP is a neural network which efficiently learns visual concepts from natural language supervision resulting in rich semantic latent space shared by both visual and textual data.It is trained on 400M image-text pairs crawled from the Internet which required little human annotation. It demonstrated a strong zero-shot capability on vision tasks, and was popularly adopted in many vision and language models. The pretrained text and image encoder in CLIP can generate useful image and text representation. In our project, we use rich semantic embedding of CLIP pretrained image encoder as a visual encoder to extract visual information from the images.

Fig 1. CLIP pre-trains an image encoder and a text encoder to predict which images were paired with which texts in our dataset. We then use this behavior to turn CLIP into a zero-shot classifier. We convert all of a dataset’s classes into captions such as “a photo of a dog” and predict the class of the caption CLIP estimates best pairs with a given image.

CLIP-VIL

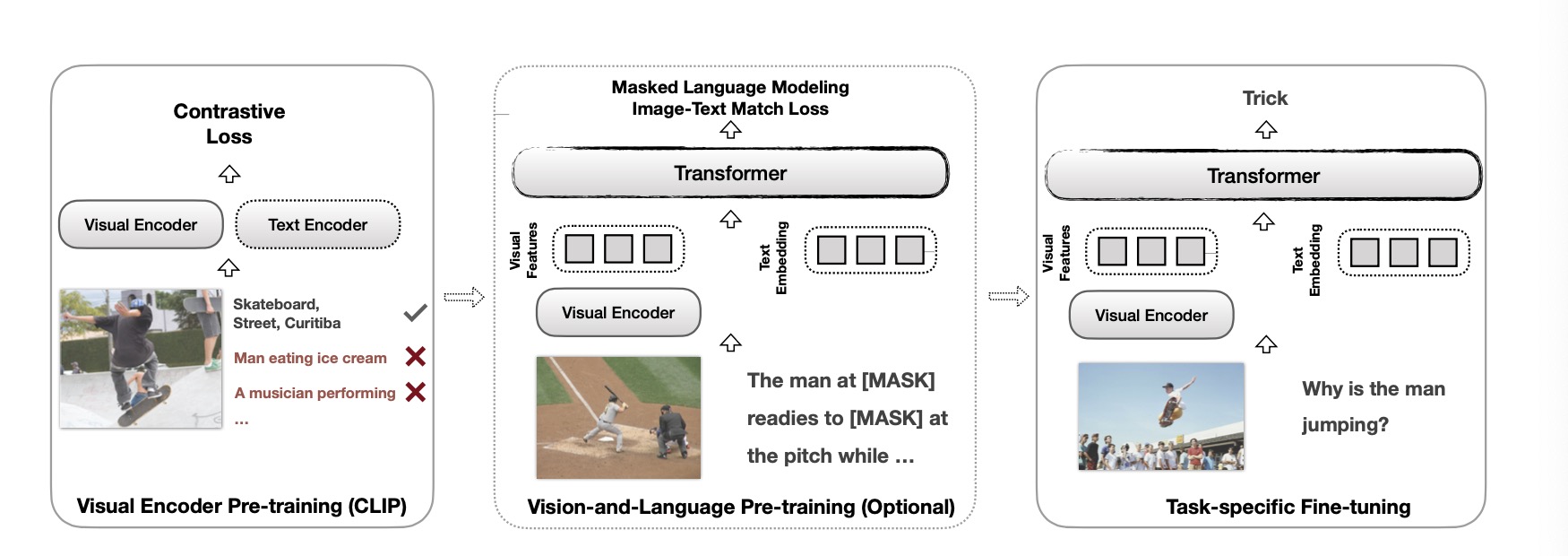

CLIP-VIL uses CLIP as the visual encoder in various V&L models in two typical scenarios: 1) plugging CLIP into task-specific fine-tuning; 2) combining CLIP with V&L pre-training and transferring to downstream tasks. The architecture consists of visual feature extraction from the pretrained CLIP image encoder, and a single transformer as language model taking the concatenation of visual features and text embeddings as inputs during training, as the architecture and training procedure shown in following the figure. In this paper, the author experiments the effectiveness of the CLIP model for image captioning with a variant of self-critical sequence training[6], which is a reinforcement-learning-based image captioning method. The authors of CLIP-ViL only experiment with one transformer which is the most basic transformer from the paper “attention is all you need”[4]. In our experiments, we will also follow the self-critical sequence training procedure used in this paper and compare the results using two types of transformers as language models.

Fig 2. The training process of a V&L model typically consists of three steps.

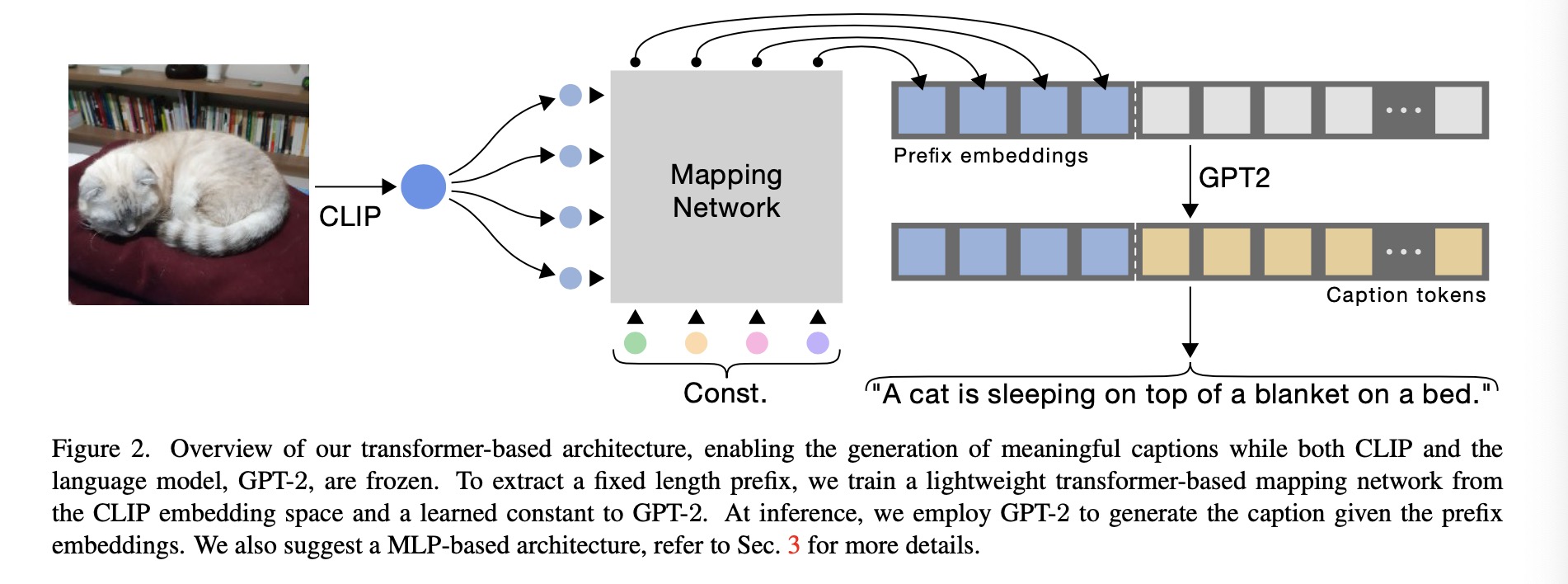

CLIP-Cap

The key idea of this paper is to use the rich semantic embedding of CLIP to extract visual information from image, then employ a mapping network to map the CLIP embedding to prefix embedding in GPT-2. After getting the prefix embedding, they feed the language model with the prefix-caption concatenation during training. In this paper, the authors have experiments on two types of mapping network: multilayer perceptron and transformer. In our case study at the later part, we will also have a comparison between the image captioning results using different mapping networks.

Experiment

Training details

CLIP image encoder will extract visual features from input images as visual encoder, and we have experimented with two types of transformer, one is the basic transformer that the reference paper CLIP-ViL use, another one is called AoANet which is from the paper called “attention on attention for image captioning”[5].

For the experiments, we follow the training procedure from the CLIP-ViL paper. The training is divided into two phrases. First phrase will train the model with cross entropy loss, and the second phrase will train the models with cider optimization using self critical sequence training. Self critical sequence training is a reinforcement learning algorithm and the goal of training is to minimize the negative expected reward. In cider optimization, the reward is the cider score of the generated sentence.

Dataset

MS COCO

The MS COCO (Microsoft Common Objects in Context) dataset is a large-scale object detection, segmentation, key-point detection, and captioning dataset. The dataset consists of 328K images. COCO Captions contains over one and a half million captions describing over 330,000 images. For the training and validation images, five independent human generated captions are be provided for each image.

Metrics

By referencing from the Clip-ViL paper, we will use the standard automatic evaluation metrics including CIDEr[5], BLEU[6], and METEOR[7].

Experiment result

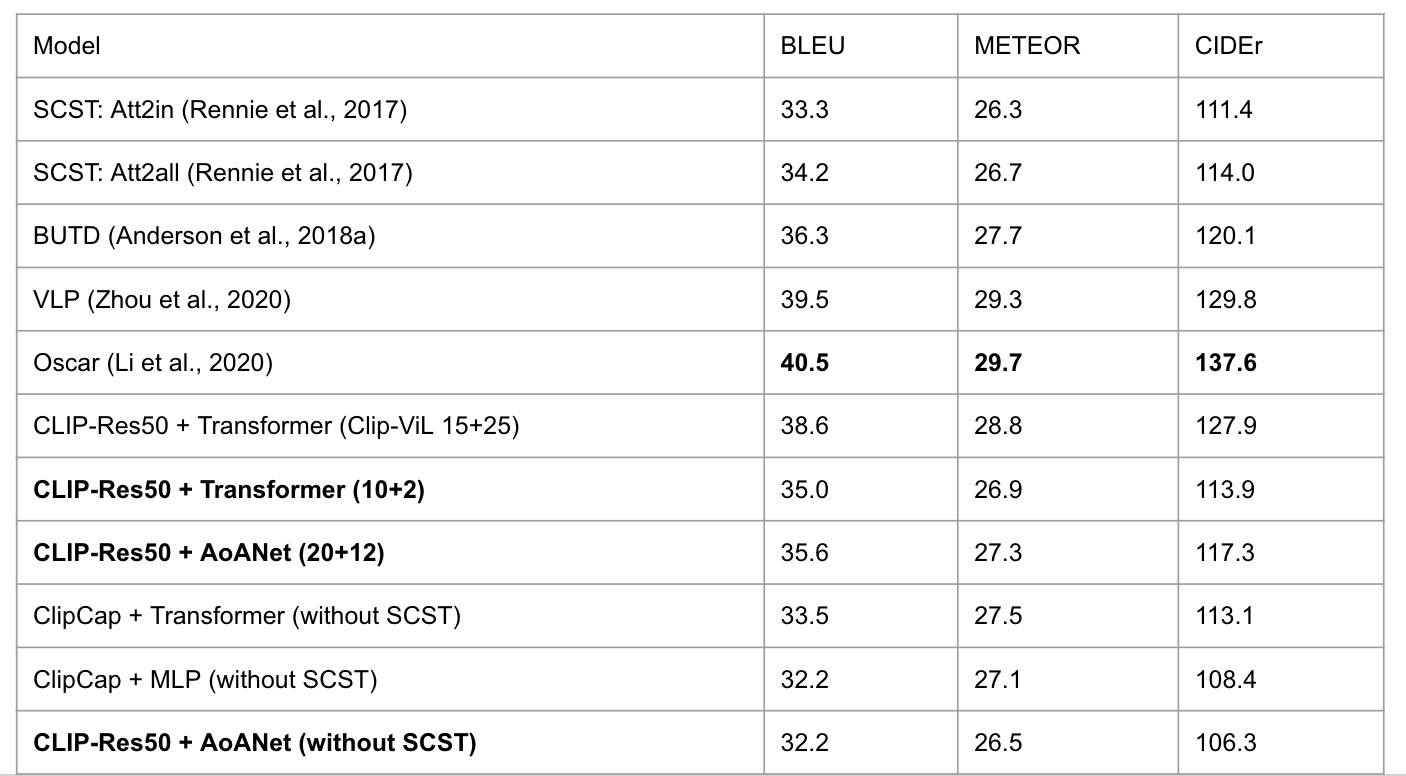

We compare our experiments with other state-of-the-art image captioning works: Att2in and Att2all models from self critical sequence training[6], BUTD[10], Vision-Language Pre-training model (VLP) [11], and Oscar[12]. These models first produce visual features using an object detection network. BUTD then utilizes an LSTM to generate the captions, while VLP and Oscar employ a transformer as language model.

Due to limited computational resources, we can only run limited number of trainining epochs so we can not get the performance that is presented in paper. However, our current model with limited training epoches can beat the two baseline transformers from SCST and achieve comparative results with the result in BUTD, which suggest that CLIP visual features can be as representative as the strong in-domain region-based feature from BUTD. The last three models do not use the cider optimization for high efficiency, so they achieve relatively lower cider scores compared to other models. Even without cider optimization, we can see that the experiment result of the ClipCap model can achieve comparable results with the state-of-art models, which also show that CLIP visual features are very powerful.

Human in the Loop

Human in the loop (HITL) is defined to induce human interaction into artificial intelligence models. It usually includes human feedback and human guidance during results generation and fine tuning.

In this project, the task of captioning generation is very human-related. In previous sections of conducting experiments, we noticed our trained models did not always produce the results in accordance to human intuition. More specifically, the models tend to use the objects taking the center or the most of the image as the subject noun of the captioning result, instead of describing other factors that might catch more interests of the user. Therefore, we decided to take advantage of human-in-the loop in our experiments for achieving a more useful and practical model.

Methods

Among the two previously studied projects using CLIP features in captioning models, we selected ClipCap as our backbone. Though ClipCap did not achieve as high scores as Clip-Vil did in automatic evaluation metrics, the dominant reason of using ClipCap for human-in-the-loop implementation was the less training time and easy inference of its implementation codes.

We used the two pretrained mapping models, one is transformer based and the other MLP based, provided by the authors of ClipCap, for the job of mapping the output of CLIP’s image encoder into the embedding space of a pre-trained language model, GPT-2 in our experiments. Then, we added an upload portal for users to upload captioning images by their choice, and also a start-word input box for them to decide the leading part of the generated captions.

For achieving the results of fixed prefix of generated sentences, we send the start word to a pre-trained GPT-2 tokenizer that translates the words into GPT-2 embedding space, and concat the embedding to the output of the original ClipCap mapping models taking in the input image. Then, we feed the concatenation into the pre-trained GPT-2 language model, which will complete the remaining sentence based both on the input image and the start word of the user’s choice.

Case Study

Generation by Different Mapping Type: Transformer vs MLP

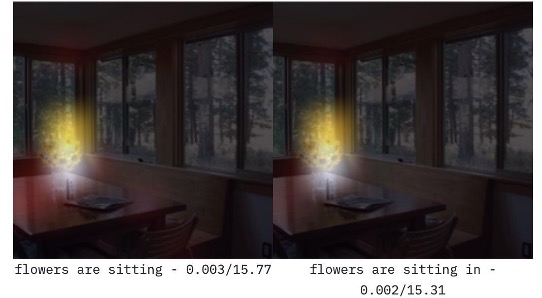

Fig 3. CoCo Dataset sample 1 with start word “flowers”. From our experiments, we observed that different mapping models in the ClipCap’s procedure of captioning generation can sometimes produce very different and surprising results. For example, we fed the start word “flowers” and Fig. 3 into both ClipCap models with transformer and MLP based mappings and achieved the following output:

Transformer: Flowers are sitting on a table next to a window. MLP Mapping: Flowers are blooming in a window sill overlooking a wooded area.

From the above outputs, we could see that the transformer based model produced a more accurate description of positioning of the flowers in the image. Instead, MLP mapping produces a very poetic and mature captioning result. One possible reason can be the linear nature of MLP mapping, so it preserved more of the original languages in the training samples of the language model. On the other hand, the attention modules of transformer architecture make it capable of describing more of the positioning in the images.

Generation by Different Start Word (COCO Image)

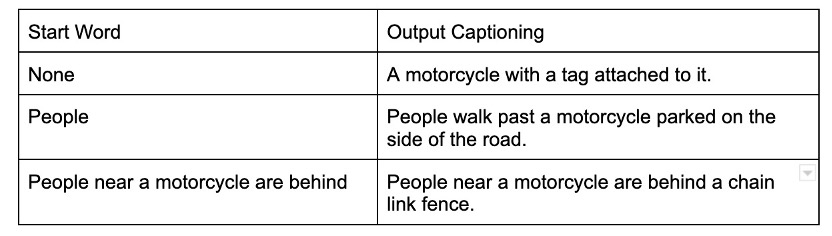

Fig 4. CoCo Dataset sample 2 with different start word choice.

After the implementation of human control start word, we noticed the outputs of the model change rapidly. Here is an example of using Fig 4 from CoCo validation dataset with different start words in the captioning model:

From the above case study, we can see that the introduction of human control significantly influenced the results of the captioning model. When a different subject is assigned, the model will also shift the entire perspective as generating the result sentence.

Other Generation Example

Fig 5. Random Image from Internet search of UCLA.

To test out the generalization capability of our implementation, we randomly downloaded an image Fig 5 from the Internet, and got the following result:

No start word: A large teddy bear standing in front of a crowd. Start word “UCLA”: UCLA basketball player with a teddy bear standing in front of a arena.

We can see that with an assigned start word, the model would generate a more relevant result in human perception. Therefore, the implementation of human-in-the-loop in the captioning model better captures the ability of CLIP-feature based captioning models.

Visualization

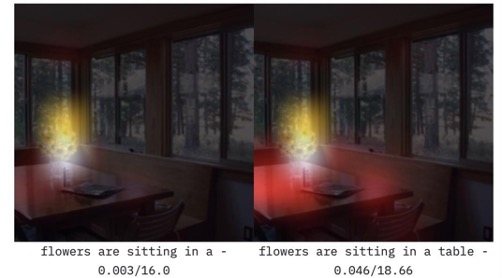

Fig 6. GradCam Visualization of captioning generation of Fig 1.

To better interpret the generation process of the captioning model, we used GradCam to visualize the generation text by text. Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) is the technique of using the gradients of the target part of language, flowing into the final layer to produce a coarse localization map highlighting important regions in the image for predicting the corresponding language concept. In this project, we used MiniClip, which is a package that enables Grad-CAM on CLIP. The above Fig 6 is an example of visualization of the generated caption in the original image.

In the visualization, we can see that the captioning generation process firstly focused on the subject itself, then as the generation progressed, the captioning generation mechanism focused more on the background positioning related to the object. The visualization demonstrates the incredible capability of CLIP’s understanding of image and confirms the strong results of captioning models using CLIP’s features.

Conclusion and Future Work

In this project, we discovered the incredible capability of CLIP’s understanding of images, and the magical chemistry between CLIP’s features and captioning tasks with human-in-the-loop. In the first part of the project, we played around many existing frameworks that utilized CLIP in captioning tasks. We aimed at reproducing their results and improving the evaluation scores upon them. Our attempts included using more advanced captioning models and introducing optimization techniques. However, due to the limitation of training time and computing resources, our results remained close to but not as high as the other state-of-the-art results. In the future, we can try other approaches, including data augmentation, to improve our results.

For the second part of the project, we implemented the human-in-the-loop feature on top of one of the current captioning models with CLIP’s feature induced (ClipCap). The experiment results and case studies reflect a very strong improvement of the models’ results after the addition of human interaction. In the future, we could improve the interaction experience by providing more controls of the generated texts.

Reference

[1] A. Radford, J. W. Kim, C. Hallacy, A. Ramesh, G. Goh, S. Agarwal, G. Sastry, A. Askell, P. Mishkin, J. Clark, G. Krueger, and I. Sutskever, “Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.00020, 2021.

[2] S. Shen, L. H. Li, H. Tan, M. Bansal, A. Rohrbach, K.-W. Chang, Z. Yao, and K. Keutzer, “How Much Can CLIP Benefit Vision-and-Language Tasks?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2107.06383, 2021.

[3] Ron Mokady, Amir Hertz, and Amit H. Bermano. Clipcap: Clip prefix for image captioning. ArXiv, abs/2111.09734, 2021.

[4] Ashish Vaswani, Noam Shazeer, Niki Parmar, Jakob Uszkoreit, Llion Jones, Aidan N Gomez, Łukasz Kaiser, and Illia Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. In Advances in neural information processing systems, pages 5998–6008, 2017.

[5] L. Huang, W. Wang, J. Chen, and X.-Y. Wei, ‘‘Attention on attention for image captioning,’’ in Proc. IEEE Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., Oct. 2019, pp. 4634–4643.

[6] Steven J Rennie, Etienne Marcheret, Youssef Mroueh, Jerret Ross, and Vaibhava Goel. 2017. Self-critical sequence training for image captioning. In Proceed- ings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7008–7024.

[7] Peter Anderson, Basura Fernando, Mark Johnson, and Stephen Gould. 2016. Spice: Semantic proposi- tional image caption evaluation. In European confer- ence on computer vision, pages 382–398. Springer.

[8] Kishore Papineni, Salim Roukos, Todd Ward, and Wei- Jing Zhu. 2002. Bleu: a method for automatic eval- uation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Compu- tational Linguistics, pages 311–318.

[9] Alon Lavie and Abhaya Agarwal. 2007. Meteor: An automatic metric for mt evaluation with high levels of correlation with human judgments. In Proceed- ings of the second workshop on statistical machine translation, pages 228–231.

[10] Peter Anderson, Xiaodong He, Chris Buehler, Damien Teney, Mark Johnson, Stephen Gould, and Lei Zhang. 2018a. Bottom-up and top-down attention for image captioning and visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 6077–6086.

[11] Luowei Zhou, Hamid Palangi, Lei Zhang, Houdong Hu, Jason Corso, and Jianfeng Gao. 2020. Uni- fied vision-language pre-training for image caption- ing and vqa. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 34, pages 13041– 13049.

[12] Xiujun Li, Xi Yin, Chunyuan Li, Pengchuan Zhang, Xi- aowei Hu, Lei Zhang, Lijuan Wang, Houdong Hu, Li Dong, Furu Wei, et al. 2020. Oscar: Object- semantics aligned pre-training for vision-language tasks. In European Conference on Computer Vision, pages 121–137. Springer.