Table Structure Recognition

In this work, we will explore ways to improve LaTeX table structure recognition. The task involves generating latex code for input table image. This will be useful in making LaTeX more accessible to everyone. We also get to understand some of the challenges involved in applying deep learning techniques, normally developed for natural images, to a different domain, specifically table images.

Introduction

LaTeX is a document preparation system for generating high quality papers. It is most often used for scientific and technical documents. It is a powerful and general tool for document creation, but this also means it has numerous features and a long learning curve that can be unintuitive to learn quickly. Automatic LaTeX generation is one way that writing and utilization of LaTeX can be made more convenient and easier for new users.

In this paper we focus on the generation of LaTeX code specifically for the creation of tables. LaTeX uses a particular syntax to create tables in its documents. This task can be broken down into 2 categories: Table Content Recognition and Table Structure Recognition (TSR). In this paper we focus on TSR, because it fulfills the needs of the new user to generate a template of LaTeX code that will compile into a table. The template has “dummy” cell contents that users can then populate with their desired data.

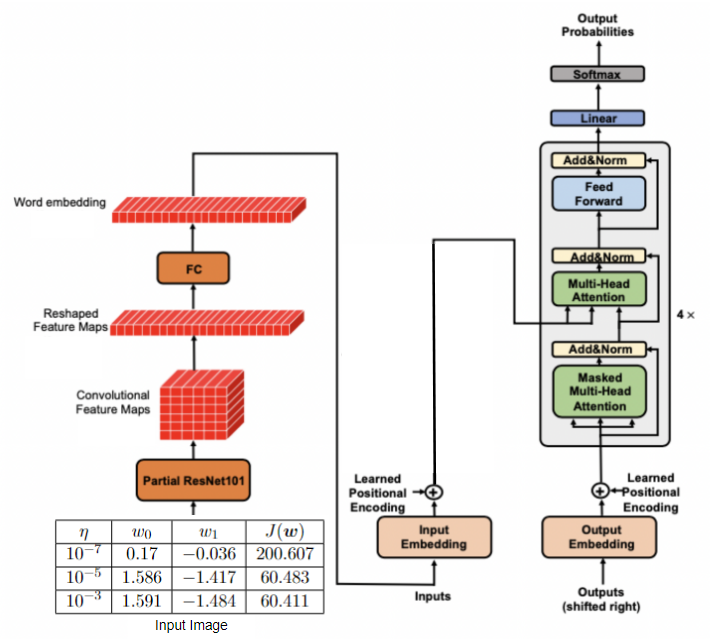

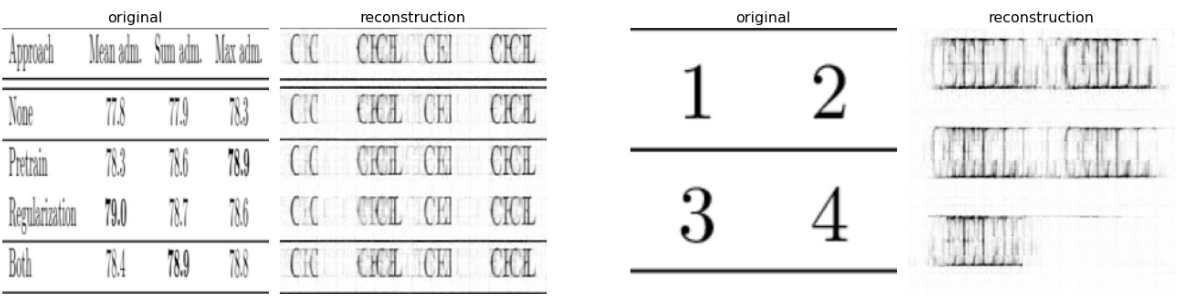

Fig 1: Table Content Reconstruction and Table Structure Recognition.

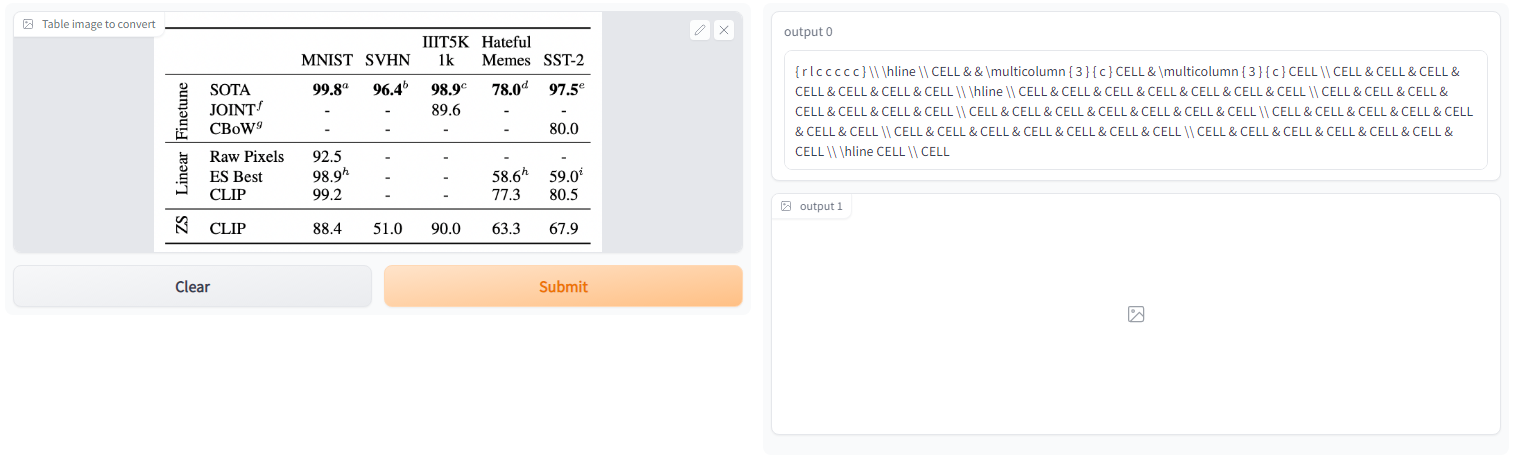

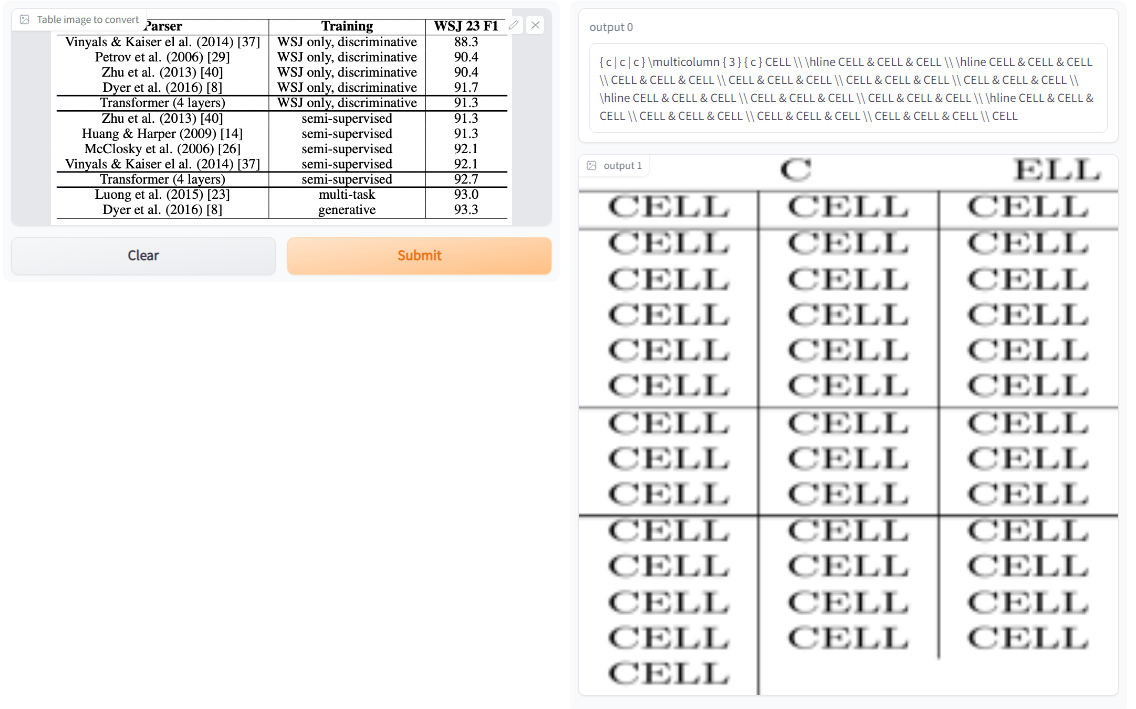

The final user interface that we present is an environment where a user can take a screenshot of a table from a scientific paper and submit it to the user interface. The image gets processed by our pipeline and outputs the LaTeX code according to the TSR task. The output is also compiled into a visualization to demonstrate that the output does successfully compile into a table that has the same structure as the input table without the cell contents.

Fig 2: User Interface with example input, output and visualization.

We approach this task using an encoder-decoder framework, using an image encoder and a text decoder. The model training requires a dataset of images of tables and the corresponding LaTeX code that generates those images. With this setup, we obtain a baseline model and explore various methods of improving the model performance. All of this is elaborated upon in the paper.

Related work

Scientific table recognition to Latex code as a task was proposed in the International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR) 2021 competition [1]. There are other related works that attempt a similar task for different documents and different programming languages/markup languages. There have been works on generating HTML code from corresponding table image [2]. Scientific table recognition can be broadly categorized as a part of document AI, which has seen a lot of interest recently [3]. There have been works to extract information from visualizations such as bar graph, pie charts etc [4].

[5] provides a solution to the table structure recognition task that we are working on. Their main focus is to improve the solution via architecture improvements using highly optimized version of MASTER work, different types of augmentations etc. However, we take a complementary approach and try to apply different pre-training techniques for the task. Document-level pre-training has been explored [6] but it is not clear which pre-training objective is suitable for image encoder [7]. We also face a similar challenge while adapting self-supervised approaches for scientific table images. In this process, we come up with a way to utilize task-specific knowledge which we describe in detail below. We also note that our findings can be combined with the findings in [5] for a superior solution.

Dataset

We use the dataset from ICDAR 2021 challenge for table structure recognition. It provides three splits: training, validation, and test sets. Training set contains around 43K image-code pairs. Validation and test sets do not contain target code sequences. Therefore, we split training set into 90:10 ratio to create train and validation set for our experiments. We use validation set to adapt learning rate schedule and for final testing of the model performance. We use word-level tokenization for the target sequence due to closed and small vocabulary. There are only 30 tokens/words in the final vocabulary. The input image has fixed resolution of 400x400. Some sample images from the training set are shown below. We find that fixing the resolution severely distorts many images and therefore it may not be ideal pre-processing. Also, the dataset is not a high quality dataset. We observe some label noise as well. Specifically, many target sequences don’t compile. We evaluate our models using word-level accuracy and sentence accuracy.

Fig 3: Good image (left), Distorted image (center), Noisy image, rows are not obvious (right).

Our Approach

We first discuss the baseline model. Then we discuss several improvements that we tried to boost the baseline accuracy. Our results are summarized in the results section.

Baseline

Given an input image containing latex table with data, the task is to generate corresponding latex code. This problem can be thought of as image captioning task and can be tackled using classic encoder-decoder framework. We first use ResNet18 as image encoder. Using transformer encoder layers on top of this, similar to scene text recognition in [8], did not improve. We leave this out for the remainder of the experiments. Our baseline model has 3 transformer layers in decoder and all but the last block of ResNet18 as encoder. The downsampling is 16x. Input image size is 400x400. Therefore, decoder input has 25x25=625 tokens. We also tried to remove the pooling layer in ResNet18 but it degraded the accuracy possibly because this significantly increases the number of tokens to 50x50=2500. Sentence accuracy for the baseline model trained for 10 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0001 and AdamW optimizer is 22%.

Fig 4: Baseline Model Architecture.

Pre-training Decoder

A common technique is to initialize decoder weights with LM trained on similar task. We use ground truth target sequences in training data to train transformer LM and use it to initialize decoder weights. The pre-training is done for 10 epochs. We transfer the LM weights to decoder and train for 10 epochs which results in more than 10% increase in sentence accuracy.

Pre-train Encoder

How do we pre-train image encoder for table structure recognition? We only have access to table images. Non-contrastive and generative self-supervised methods can be used. However, the former makes use of two different views of same image and minimizes distance between them. The problem with this approach for our task is that two random crops from same table image do not have any semantic similarity. Therefore, we use a different approach to obtain image pairs with same table structure. We compile the ground truth target sequences to obtain dummy tables. These tables differ from original tables in term of content only as shown below. The newly generated image and its original image can be considered as two different views. Now we can use the non-contrastive approaches. We do not experiment with contrastive methods due to their requirement of large batch size for hard negative mining. We discuss all the pre-training methods below.

Fig 5: Example original table and dummy table.

Curriculum Learning

We hypothesized that dummy table images are easy examples of table images due to simplicity of table content. This is in contrast with original table images whose content is not relevant for the task but can vary a lot. Therefore, we can leverage this in curriculum learning framework by first training the entire model end-to-end using dummy table images and ground truth sequences. Then the learned weights are trained again on original table images and target sequences. However, it does not work since the accuracy of the final model is same as in the case where image encoder is randomly initialized before training on original dataset. The reason can be the difference in input data distribution. It would be interesting to see if the exact opposite holds, i.e. does pre-training the network on the original images improve structure recognition of dummy table images?

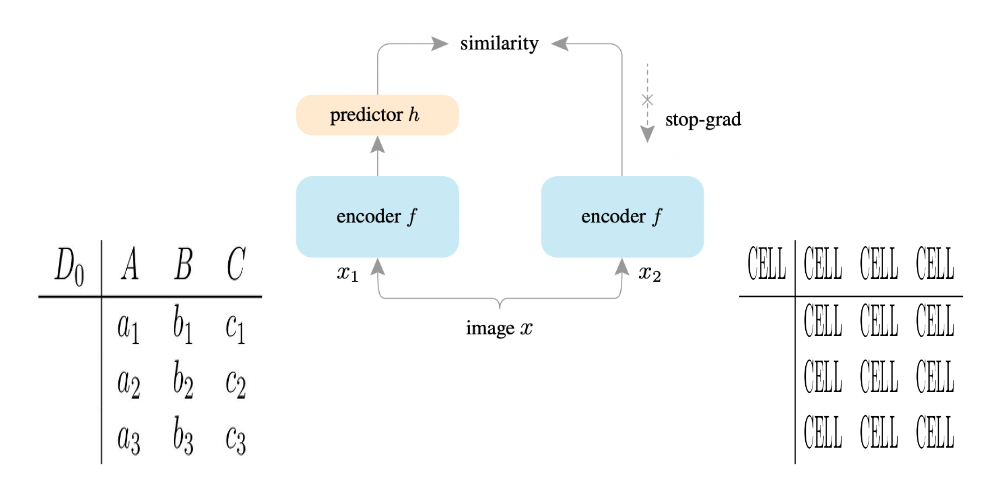

Non-contrastive Pre-training with SimSiam

Although contrastive/non-contrastive pre-training heavily depends on image augmentation, we still experiment with one such approach despite limited data augmentation available for our task. We explore SimSiam [9] due to its simple and effective approach in unsupervised representation learning. As discussed earlier, we can use dummy table and corresponding original table images as two views. We try to minimize their distance in some latent space as shown below. The network is trained with negative cosine similarity loss. However, we find that the loss reaches around minimum value of -1 after few epochs indicating that the image encoder collapses to a degenerate solution. There could be multiple reasons for this: limited dataset, no augmentation, inherent difficulty of task. We found other users facing similar challenges when pre-training on different datasets.

Fig 6: SimSiam approach.

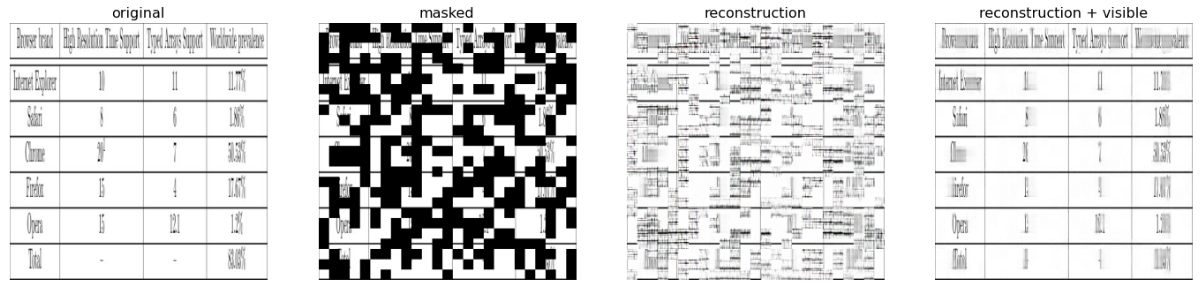

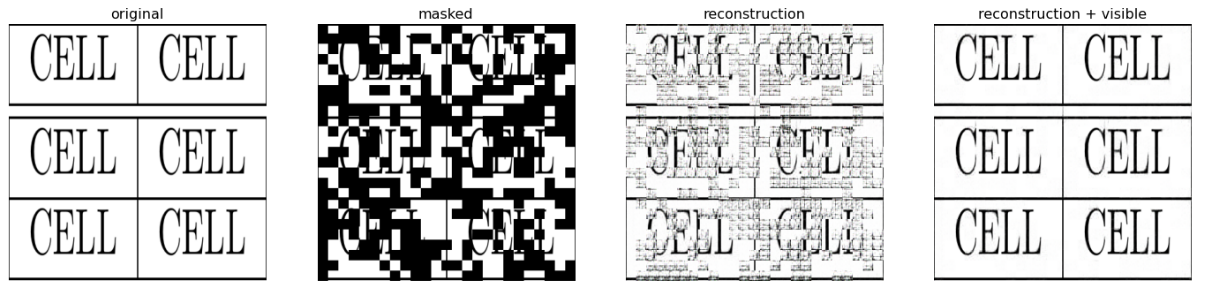

Generative Pre-training with MAE

We can use masked autoencoder (MAE) [10] for pre-training. Conceptually, algorithms based on MAE should not be useful for our task despite being able to successfully reconstruct the table structure (content may be difficult to reconstruct with limited data). The reason being MAE makes the assumption that the masked regions can be filled using global knowledge of what object is present in the image as well as local information such as color etc. Here, we want the model to learn global semantics of table structure. But there is no way to force the model to learn to do so because table structure, i.e. horizontal and vertical lines can be filled in the masked region with local knowledge itself. The content of the table is difficult to reconstruct with limited data. We observe these in the experiments also. If we simplify the table content by using dummy table images, we find that the model is able to almost perfectly reconstruct the input image as shown below. Similarly with the original images, model is able to reconstruct the horizontal and vertical lines. However, it does not bring any performance gain for our task.

Fig 7: MAE reconstruction of actual table image.

Fig 8: MAE reconstruction of dummy table image.

Pix2Pix Style Generative Pre-training with ConvMAE

We can force the model to reconstruct the dummy image given original table image as input. This should help to learn the global table structure present in the original image. Why does this make sense? This is because there is no straightforward relationship between pixels of the two images which can be exploited for this reconstruction task. The only way we can reconstruct the dummy table is by knowing the table structure of original image, i.e. focusing on rows and columns. This is in contrast with the previous approach. The caveat here is that model may find it difficult to reconstruct the dummy image perfectly with limited training as shown below. It is not clear if the model learns table structure or some spurious correlations.

Fig 9: ConvMAE reconstruction of actual table image.

Fig 10: ConvMAE reconstruction of dummy table image.

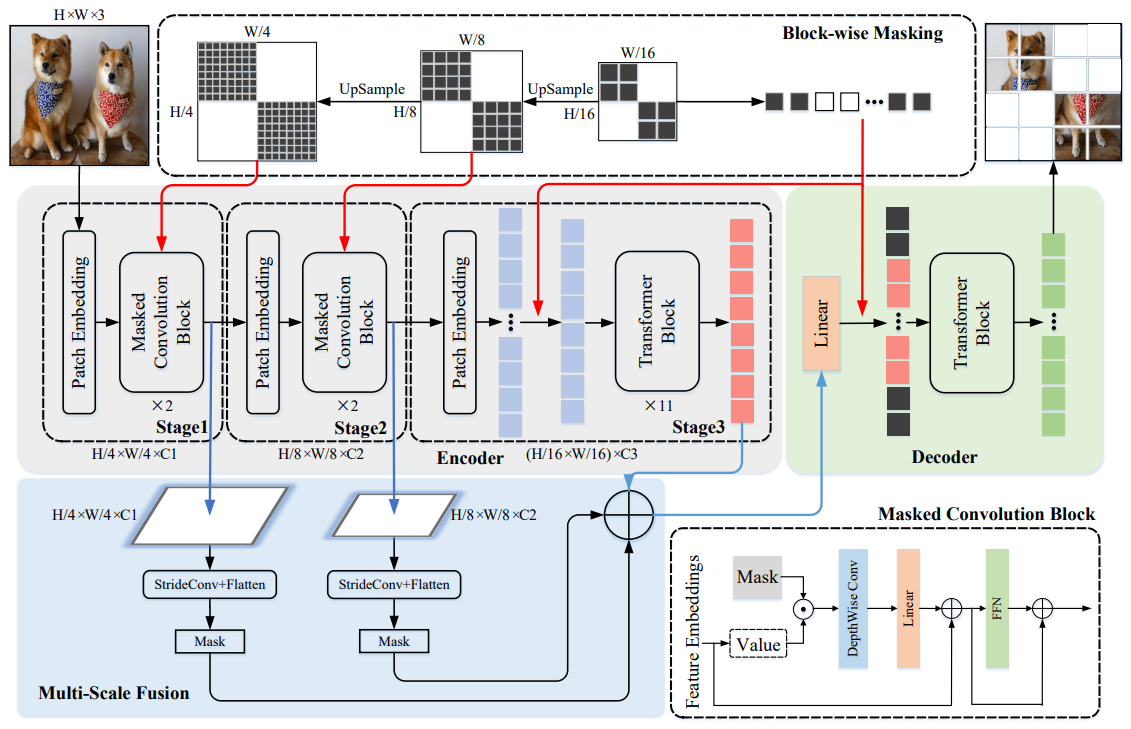

We make an extra change. We use ConvMAE [11] instead of MAE because of its multi-scale hybrid convolution-transformer architecture, which has shown improved performance over the MAE architecture. In our experiments, we use the base configuration. It uses image size of 224 with a progressive downsampling of 16x. Therefore, we have around 32x downsampling if we compare with the original resolution of 400x400. We tried to use the original resolution but it increases per epoch training time from 30 minutes to around 2 hours, which makes training for even 10 epochs impractical. There are 15 encoder blocks and 8 decoder blocks. Encoder transformer blocks use 12 attention heads whereas decoder transformer blocks use 16 heads. More details about the architecture can be found at the official GitHub implementation [12].

Fig 11: ConvMAE Architecture [6].

We pre-train the image encoder for 40 epochs. For finetuning, we use three variations mainly in the decoder block: 1. 8 pre-trained decoder blocks 2. 4 pre-trained decoder blocks 3. 4 pre-trained + 4 randomly initialized decoder blocks. The entire network contains more than 100M parameters and is trained with learning rate of 0.0001 for 20 epochs. We find that all three variations achieve same validation loss after 20 epochs but the first variation has lower sentence accuracy than the other two cases. Nonetheless, this pre-training performs much better than the other two self-supervised pre-training strategies discussed above in terms of improving over corresponding randomly initialized model. Finetuning pre-trained ConvMAE has 8% better sentence accuracy than ConvMAE trained from scratch (row 5 vs row 7 in results table below). Also, the best performing convMAE has sentence accuracy very close to the baseline architecture with pretrained decoder and trained for extra 10 epochs (row 3). However, it is difficult to draw conclusion due to different encoder architectures and model sizes.

Post Processing

Sometimes the model outputs LaTeX code that does not compile. Upon analysis it was found that this happens when there is a mismatch in the number of table columns expected by 2 different parts of the LaTeX code.

We resolve this by performing post processing on the output. By checking every row of the code, we count the number of columns it expects. We set the mode of all the number of columns expected as the true number of columns expected. Then, we check if any part of the code does not match with the true number of columns expected. If there is a part of the code that does not match, we correct it and update the output.

By performing this post-processing we were able to correct many common test images that output code that did not compile properly. This post-processing is essential because helping new users to adopt LaTeX means that we must provide them with code that is compiling successfully rather provide them with code that does not compile and needs to be debugged.

Results

| Model | Validation Loss | Word Accuracy | Sentence Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (ResNet18 + 3 transformer decoder layers) | — | — | 22% |

| + Decoder Pre-training | — | — | 32% |

| + 10 epochs | 0.076 | 92.1% | 49.1% |

| MAE | 0.140 | — | — |

| ConvMAE Baseline (Random initialization) | 0.119 | 90.0% | 40.0% |

| ConvMAE (8 pre-trained decoder blocks) | 0.107 | 90.9% | 44.1% |

| ConvMAE (4 pre-trained decoder blocks) | 0.109 | 92.6% | 48.7% |

| ConvMAE (4 pre-trained + 4 randomly initialized decoder blocks) | 0.107 | 91.9% | 48.2% |

Demo

Our best performing model is hosted here on HuggingFace spaces. Interested readers can navigate to the page and input desired tables to see model’s outputs.

Fig 12: Recording of a sample image being input to the model and generating the corresponding output code and output table.

Error Analysis

The model performs poorly on particular test images. Below we analysis certain modes of failure.

White Space Bordering

We find that the model makes mistake when white spaces are bordering the input image. This is because the training data contains tightly cropped images. Removing the white space corrects some of the issues.

Fig 13: Table image with white space border generates code that does not compile.

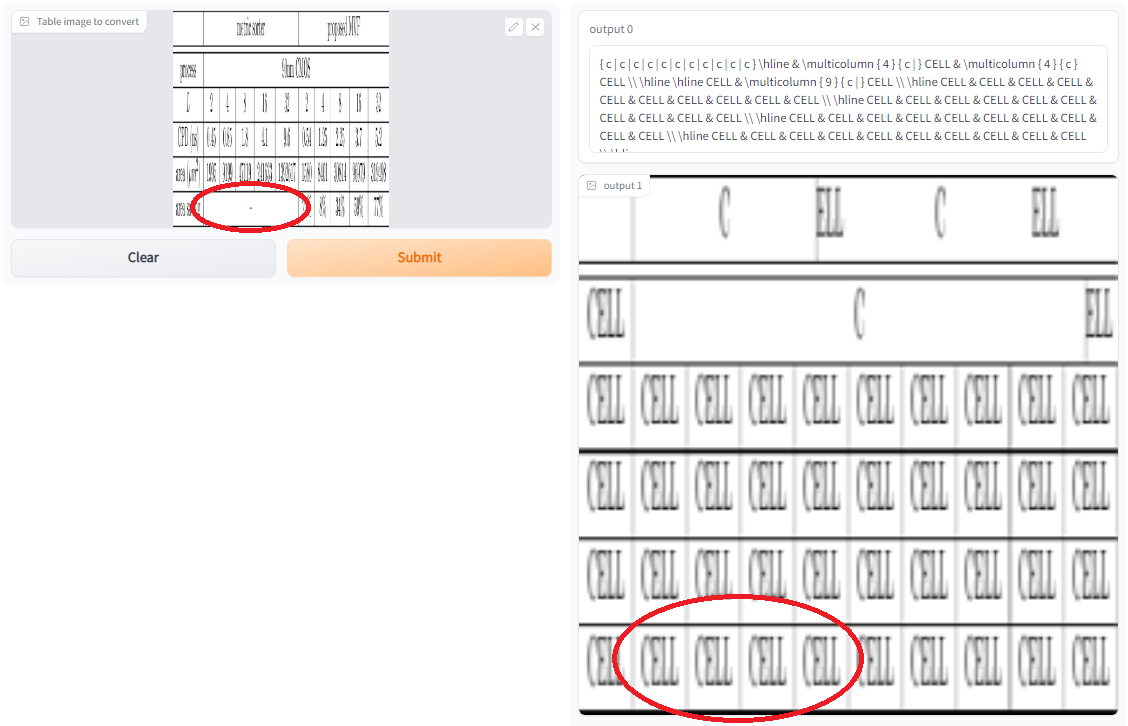

Multicolumn entries

Multicolumn entries are also hard to detect for the model and difficult to reproduce.

Fig 14: Multicolumn entry in table image did not get detected, see circled in red.

Multiline rows

Not all rows of a table are followed by a horizontal line. Some rows consist of multiple lines. In such situations, the model makes mistakes and can get the row boundaries wrong.

Fig 15: Table image with unexpected row boundaries does not get output correctly.

Future Work

- 95% Exact Match Metric - So far we have been using word accuracy and sentence accuracy to evaluate the model. However, these metrics are not perfect. In sequence to sequence generation, 95% exact match is a common metric used in research to measure model performance. Our model is a good use case where that metric would be insightful and also beneficial for analysis.

- Beam search decoding - Currently we are using the greedy search decoder. A beam search decoder is likely to be slower but more accurate in performance.

- Artificial dataset - We have been using the dataset from the ICDAR 2021 challenge. This dataset has noisy images and distorted images. We could construct our own artificial image dataset by randomly changing the number of rows, columns and other features in LaTeX code and rendering multiple different table images.

Conclusion

Identifying table structure from images is a non-trivial task. We find that the baseline model performs decently. However, it is difficult to apply pre-training techniques directly to a different domain. We identified some critical shortcomings in adapting algorithms developed for natural images to table images and provided plausible alternatives. Our solution requires parallel data but it is relatively easy to obtain as compared to other computer vision tasks. It is possible that we may see even larger benefits of the proposed pre-training scheme if we perform the experiments with a large dataset and train much longer.

References

[1] Kayal, Pratik et al. “ICDAR 2021 Competition on Scientific Table Image Recognition to LaTeX.” ArXiv abs/2105.14426 (2021)

[2] Nassar, Ahmed Samy et al. “TableFormer: Table Structure Understanding with Transformers.” ArXiv abs/2203.01017 (2022)

[3] https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/document-ai

[4] Zhou, Fangfang et al. “Reverse-engineering bar charts using neural networks.” Journal of Visualization 24 (2021): 419-435.

[5] He, Yelin et al. “PingAn-VCGroup’s Solution for ICDAR 2021 Competition on Scientific Table Image Recognition to Latex.” ArXiv abs/2105.01846 (2021)

[6] Li, Junlong et al. “DiT: Self-supervised Pre-training for Document Image Transformer.” ArXiv abs/2203.02378 (2022)

[7] Huang, Yupan et al. “LayoutLMv3: Pre-training for Document AI with Unified Text and Image Masking.” ArXiv abs/2204.08387 (2022)

[8] Feng, Xinjie et al. “Scene Text Recognition via Transformer.” ArXiv abs/2003.08077 (2020)

[9] Chen, Xinlei and Kaiming He. “Exploring Simple Siamese Representation Learning.” 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) (2021)

[10] He, Kaiming et al. “Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners.” ArXiv abs/2111.06377 (2021)

[11] Gao, Peng et al. “ConvMAE: Masked Convolution Meets Masked Autoencoders.” ArXiv abs/2205.03892 (2022)

[12] https://github.com/Alpha-VL/ConvMAE