SketcHTML - An interactive sketch to HTML converter

The area of Web-UI design continues to evolve , often reqiuring a balance of effort between designers and developers to come up with a suitable user interface. One of the key challenges in standard Web UI development involves reaching an interface between desginers and developers, in being able to convert designs to code. To this end, several works in recent years have taken atempts to try and automate this task, or provide for easy conversion from design to code. Works such as Microsoft sketch2code and pix2code , provide automation by converting sketches and screenshots respectively to code. However, there still remains room for further work in this domain, such as including more element types, encoding more information in the sketch and allowing for more variablity. This project seeks to improve upon the Sketch-to-Code framework, by first constructing an enriched dataset of Web-UI samples and then allowing user manipulation of the generated web-page through an interactive user interface as well as allowing custom generated images using GANs.

Introduction

The standard pipeline in a web-development process today involves drawing up a design, and then hiring a developer to realise this design into an actual HTML page. This requires a significant investment of both money and effort on the part of the user. Furthermore, inspite of this investment, there is not always a clear consensus between the designers, developers and clients, and they often do not receive the interface they actually desire. The developer thus serves as an extra link between the user's sketches and the creation of computer code.

This project seeks to attempt to automate the role of the developer in this pipeline. Aiming to serve as a "no-code" tool, the project seeks to take in a hand-drawn sketch of a HTML page, and convert it into HTML code, rendered for the user to see. We seek to improve and extend upon existing sketch-to-code applications, by allowing more variations in the layouts generated and an interactive tool for styling and manipulation. In particular, the contributions of the project can be described as below:

- To utilize and extend software that can generate Web-UI images to generate an enhanced dataset comprised of sketches and layout files referred to as gui files.

- To utilize and improve on an existing model architecture to generate HTML code using a two-stage pipeline from image to code.

- To develop an interactive user-interface that allows for uploading sketches, generating corresponding HTML pages, and manipulting these pages with styling on the fly to create a desired HTML output.

- To leverage the power of a text-to-image GAN to allow users to add caption-generated images to the website.

The rest of this report is divided as follows. The Introduction is followed by a description of the Related work, followed by a Video Demonstration of the tool. We then describe in detail the Methodology in moving from sketch to code , followed by a Results section that provides qualitative and quantitative analysis. Finally, the report provides an insight into Future Work in this domain.

Related Work

Automated Web-UI development continues to be an active area of research. This task is demonstrably difficult, given the nuances of understanding the layout information from the given sketch or input, including the relative spacing and latent information embedded in the sketch, as well as allowing for stark variations in generated outputs. This section seeks to shed light on some of the notable approaches taken towards attempting to achieve this goal.

Datasets

The discussion towards automated Web-UI generation begins with a discussion on the datasets. One of the fundamental problems in addressing this task is the lack of a publicly available dataset suitable for training. While works such as Microsoft sketch2Code[1] only publicly release their validation dataset (comprised of about ~150 samples), other works , such as pix2Code[2], the project by Ashwin Kumar[3] and other attempts[4],[5] all make use of the pix2Code dataset. This dataset, which provides the underlying base structure for our dataset, is comprised of an image and its corresponding layout(gui) file. Applications such as [3] and [4] leveraged this dataset by manipulating the CSS of the webpages in the HTML screenshots to make them look like sketches. A key issue of this dataset however, is that it is constrained to one layout, as shown in Figure 1 below. This forces all models and applications trained on this dataset to conform to producing outputs according to this layout.

Fig 1. The samples from the pix2code dataset[2] all conform to the above layout format[3]

In contrast to the Web-UI space, mobile application design generation tasks have better dataset coverage including sources such as Google Material Design[6] and RICO [7]. These datasets provide extensive examples suited for various tasks, and thus support better generalization towards developing effective app-design generation models.

A notable mention is the Web Generator tool [8]. This tool allows for the random generation of Web-UI images and HTML codes, allowing users to specify layout specific proabilities such as presence/absence of a header/sidebar, number of components etc. Our project leverages and extends this tool , as will be seen in the methodology section, to generate our enhanced dataset.

Applications

Several notable attempts have been made to automate the task of web-UI generation, using different starting points. While some applications such as [1],[3],[4] and [5], similar to our use-case, convert hand-drawn sketches to code, applications [2] and [9]convert images/screenshots to code. Our project is based off of the work done in [3] which converts the problem to one of an image-captioning[11]problem, where the image is the hand-drawn sketch, and the corresponding caption is the layout(gui) file. These models work well on their "element set", which by nature of the problem at hand, is limited to the tags present in the created dataset and restricted to the limited layout forms in the training dataset. However, the projects in [4] and [5] suffer from poor generalization because of the aformentioned constrained layout in the underlying dataset. Microsoft's sketch2code[1], hosted on their website, remains a key player in this space, with the additional power of using OCR to add handwritten text to the generated output as well. However, the workings of the model as embedded within the Azure framework, and as can be visualised on their website, even this model is not free from errors. Some other works on this task also include drag-and-drop tools such as Sketch[14] and Bubble[15]

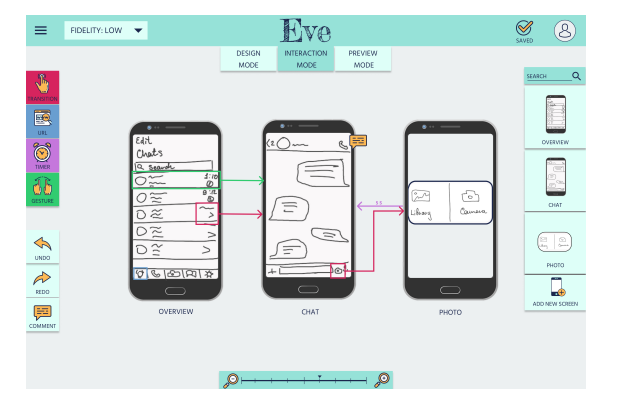

Fig 2. The EVE tool[10]

A notable mention is the tool Eve [10], which generates high-level code for app design from sketches, while allowing for custom styling and flexibility. This application performs color and other detailing on the tool and requires sketching to be done on the tool. In contrast, our project aims to allow for any hand-drawn / tablet-drawn sketch to be uploaded into the tool, allowing for flexiblity. The tool also does not expose any code/results apart from a single set of screenshots, which limits the study of its extensiveness.

Video Demo

Methodology

The methodology of the proposed project is described as follows. We begin with a discussion on the dataset generation, involving the generation of sketches and gui files. We then descibe the model architecture to move from sketch to output in detail. Finally, we provide some information on the interactive tool development.

Dataset Generation

The first step in the process involved generating a custom dataset. As discussed in the previous sections, one of the key issues with existing datasets in this space is the restriction to a fixed layout. In order to remedy this and allow the develpoment of a model that can predict well on several layouts, we first undertake the generation of a new dataset.

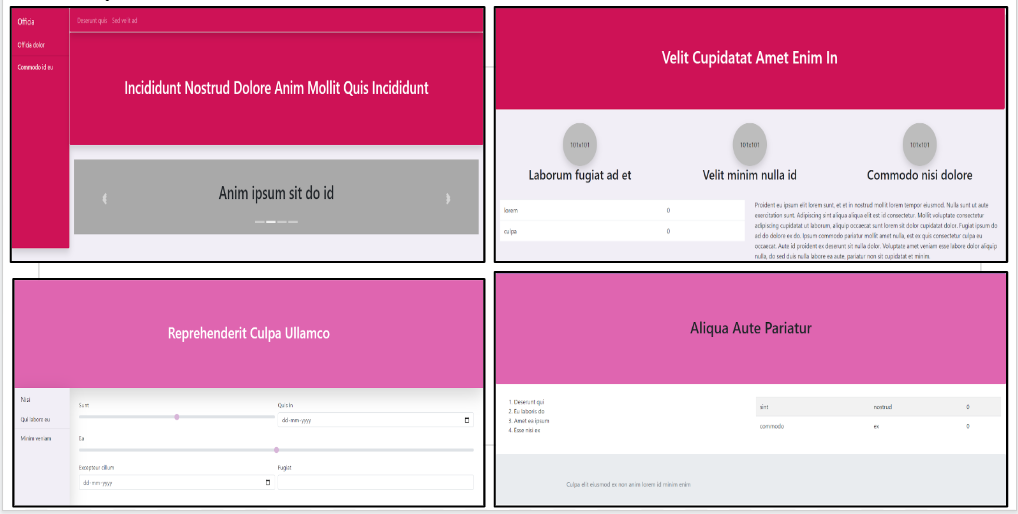

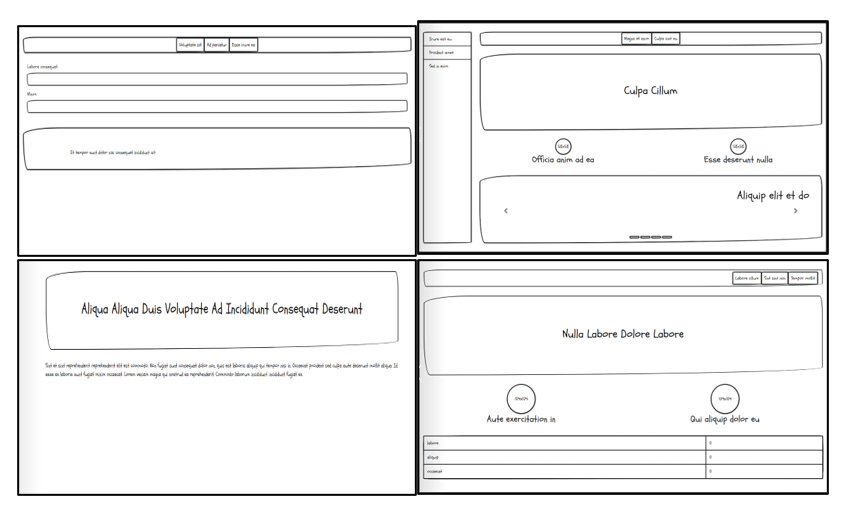

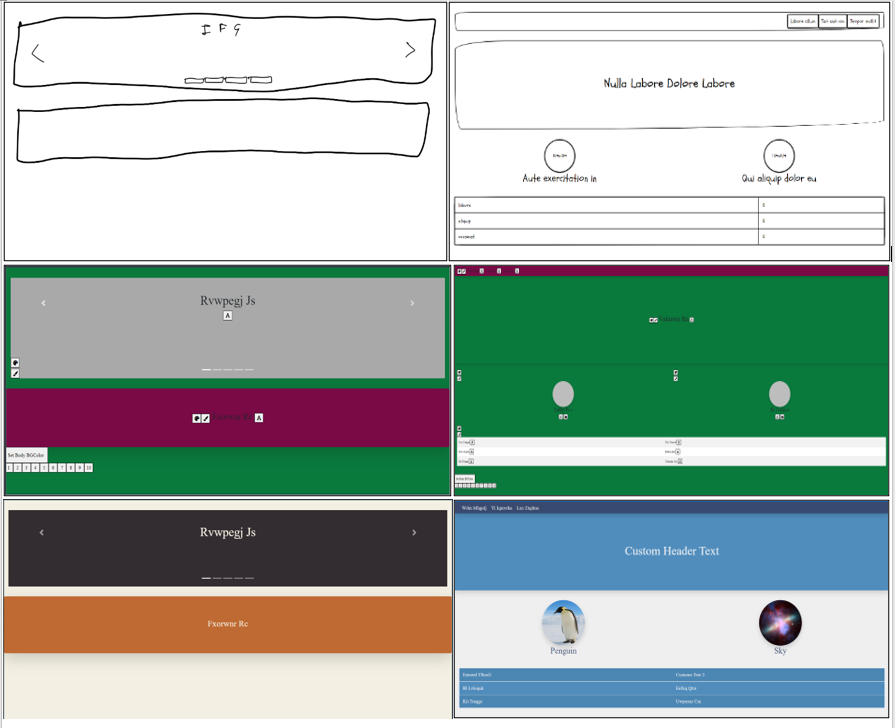

Fig 3. Samples generated using the Web-Generator tool

To this end, we make use of the Web-Generator tool[8]. As shown in Figure 3, this tool can be used to randomly generate Web-UI screenshots. However, the expected dataset in our use-case is of the form (sketch, gui file). Thus, we incorporate the generation of these two components in the above tool.

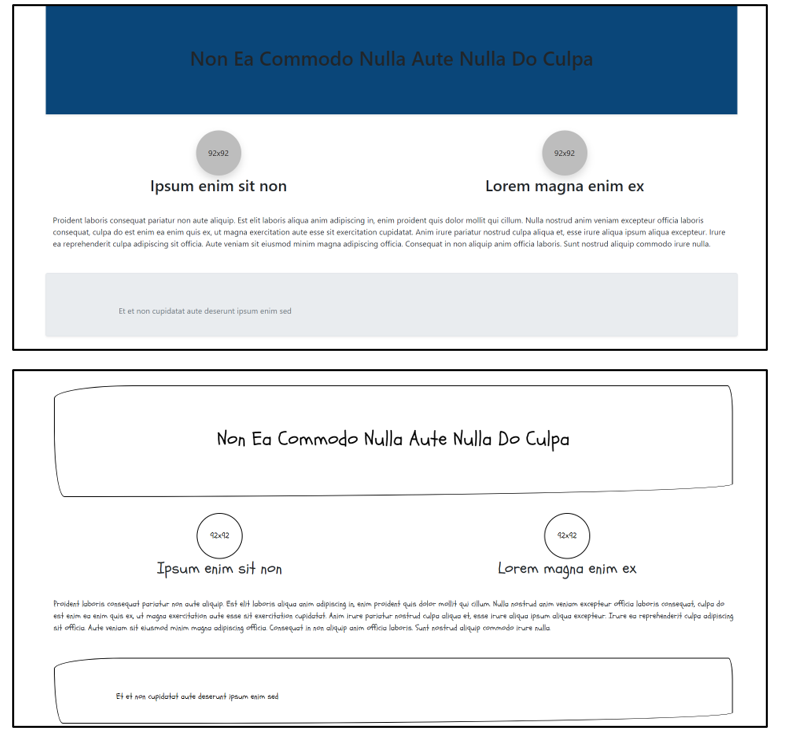

In order to generate the sketches, we make use of CSS manipulation as hinted at in [3], modifying properties such as the box-shadow, border-radius and font-family of the HTML code to make it look sketch like. Figure 4 demonstrates the conversion of a HTML webpage to its corresponding sketch view. Through the process of repeated trial-and-error, we were able to obtain the required CSS to allow the outputs to look as sketch-like as possible. We also extend on this principle and create multiple variations of the CSS with different rouding and shadowing to introduce random variations, in order to account for the random variations traditionally associated with human drawn sketches.

Fig 4. Conversion of UI screenshot to its corresponding sketch form

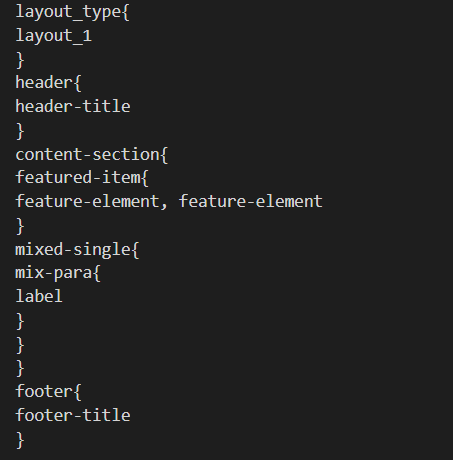

In order to generate the gui files, we embed the collection of the various components as the website is being generated. In this manner, while the code generates the website image, it also creates a record of the various components in the website and their relative hierarchy and ordering. This information is then used to create a layout file, henceforth refered to as gui file. Figure 5 demonstrates a sample GUI file for an image.

Fig 5. GUI file for the layout shown in figure 4

In this manner, we completely overhaul the Web-Generator tool to serve our purpose of dataset generation, shifting it from generating screenshots to a combination of sketches and gui files. Additionally, the nature of the tool allows to specify probabilities for the various aspects of the generated UI samples, such as layout probability, probaility of particular components occuring etc. This allows for sufficient randomness in the samples present in the dataset, as shown in figure 6. A great advantage of this approach also lies in its extensibility, in adding more components, layout styles etc.

Fig 6. Randomness and variation in the dataset samples

Model Architecture: GUI file generation

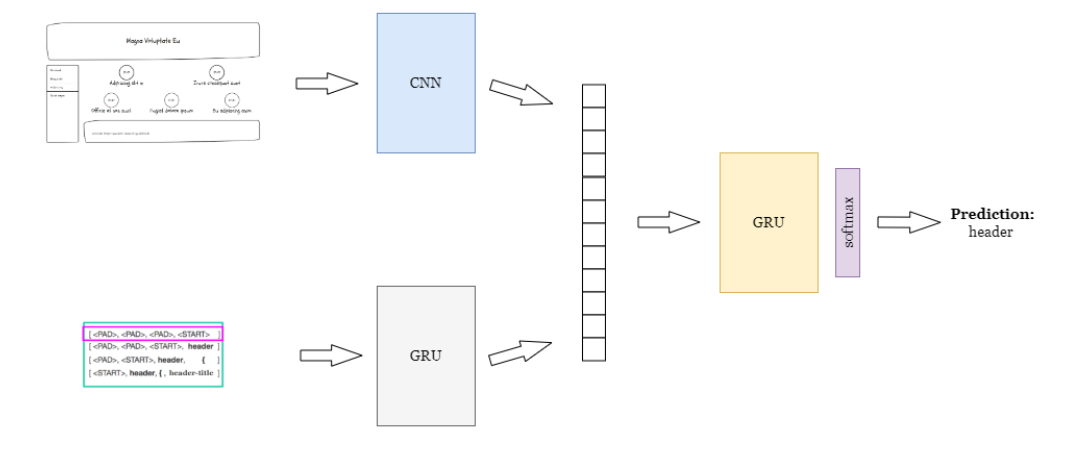

Using the created dataset, we train an encoder-decoder[12] architecture in order to generate the required outputs. The base architecture is derived from the work done in [3]. Figure 7 below shows high level design of the model.

Fig 7. High Level overview of the model architecture

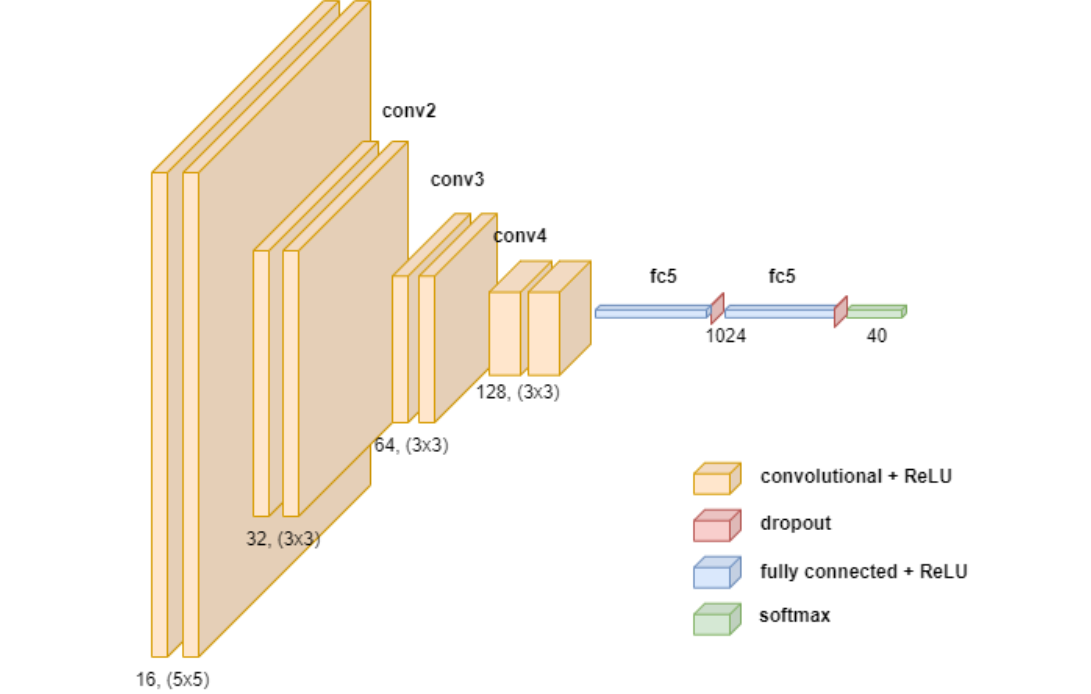

This model is inspired by the image captioning model[11]. First, a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) is used to extract image features from the source image. This serves as the image encoder in the architecture. The architecture derives off of the VGG[13] architecture, with slight modifications as shown in Figure 8. Most notably, the initial layers make use of a 5x5 kernel instead of a 3x3 kernel, in order to detect larger features at the start. Similar to [3], the architecture also does not use any max-pooling layers, and instead the last layer at each convolution size uses a stride of 2 to downsample the image. We also add an additional 128 channel layer as opposed to [3] in order to facilitate better feature learning, given the extra amount of detail and variation present in our train dataset.

Fig 8. Detailed architecture for the CNN

Parallely, a language encoder is created using a Gated Recurrent Unit and an Embedding Layer, in order to encode sequences of the source code tokens. The language encoder makes use of a pre-defined vocabulary , which includes the various element types described in the previous section. This is then followed by a a decoder model again comprised of GRU units, which takes in the output from the previous two steps as its input, and predicts the next token in the sequence, using a softmax prediction on one of 'n' classes, where 'n' is the size of the vocabulary.

To train the model, the source code is broken down into token sequences. Each of these sequences serve as a single input for the model, along with the input image, and its label is the next token in the document. The loss function for the model is the cross-entropy cost, which compares the model's next token prediction to the actual next token.

When the model is charged with producing code from scratch during inference, the approach is slightly different. The CNN network is still used to process the image, but the text process is just given a starting sequence. Each step adds the model's prediction for the next token in the sequence to the current input sequence, which is then fed into the model as a new input sequence. This approach is repeated until the model predicts an "END" token or the number of tokens per document reaches a predetermined limit.

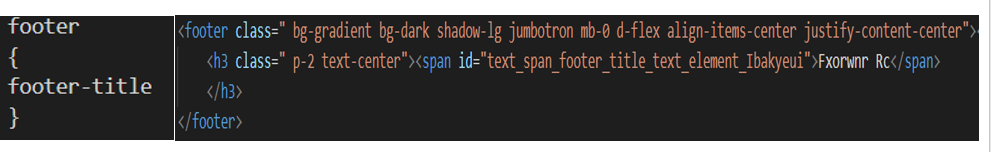

Model Architecture: Generating HTML from GUI

The encoder-decoder model previously described outputs a layout(gui) file, comprised of the various components present in the page. We then use a compiler code in order to convert each of these tokens into their corresponding HTML components. The process involves generating a tree-like structure based on the hierarchy defined in the gui file, where for each level in the tree, the element is replaced with the corresponding HTML text, defined in a seperate json mapping file. In doing so, we also dynamically embed the required JavaScript and CSS information needed to make the generated output interactive. Figure 9 below denotes a sample GUI , and its corresponding converted HTML code.

Fig 9. A snippet of gui code and its corresponding HTML

The base logic for the compiler is dervied from [3], however it is heavily altered and enhanced to reflect the new task at hand.The compiler uses layout information encoded in the gui file to determine the relative placing of components by including the necessary CSS classes as required. Additionally, each of these components are provided a dynamic id in order to ensure interactivity, which is also produced through the compiler output. Once the entire gui file has been converted, the compiler adds the necessary post-processing and text-processing the convert the code to a readable format.

Experimental Settings

In this section, we provided a brief description of the experimental settings. The training purposes involved using a dataset that contained 3000 examples with a train-test split of 85% / 15%. Additionally, while the model defined in [3] used the RMSProp optimizer, we observed better results using the Adam optimizer, as demonstrated in the following results section. The model was trained using Google Colab Pro on a Tesla P100 GPU for 75 epochs, with an adaptive learning rate. The first 50 epochs used a learning rate of 1x10-4 and the remaining epochs used a learning rate of 1x10-5M. The images are resized to a size of 256x256 before being fed to the image-encoder model. Additionally, the model uses a vocabulary of size 40.

Creating the interactive tool

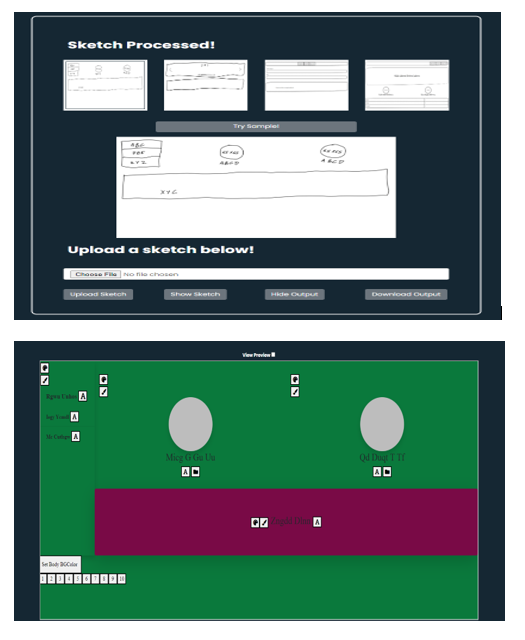

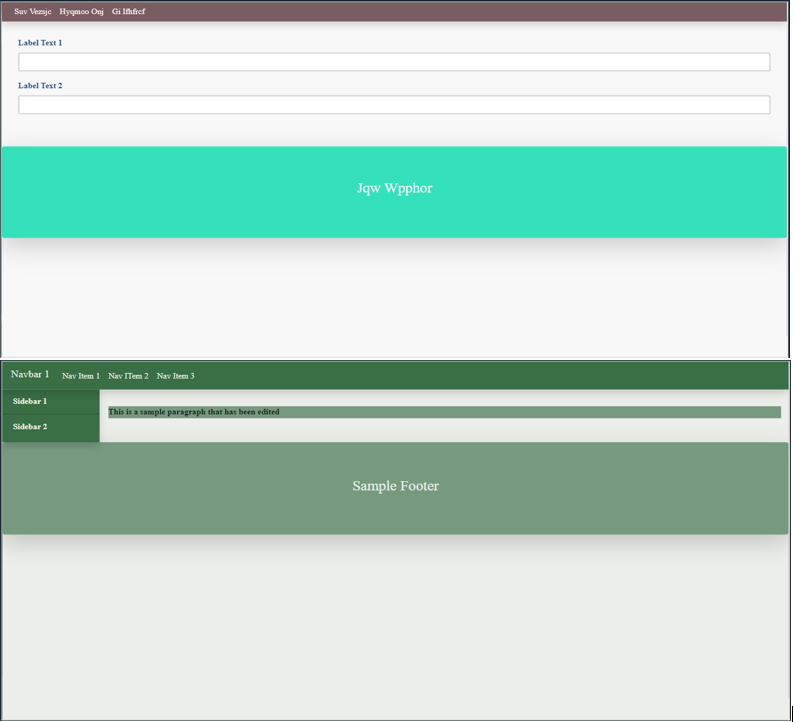

A key charge of this tool in making it human-centric , was to serve it up as an interactive tool. We make use of the Flask API tooling[14] provided by Python in order to facilitate this. Specfiically, the application is conveted into a client-server application. Figure 10 demonstrates a view of the user-interface.

Fig 10. UI for the tool. Top: Modal to choose/upload sketch image. Bottom: Interactive HTML generated.

As demonstrated in the video demo, the user can choose one of the pre-defined sketch examples, or upload their own. When the "Upload Image" button is pressed, the client makes a call to the back-end Python server, which internally takes the image and calls the model prediction on it. Once the model makes its prediction and the compiler creates and saves the corresponding HTML file, the server returns this file path to the client, which then renders to corresponding interactive HTML to the user.

The interactive features provided by the tool include:

- Uploading a pre-defined sample or custom sketch

- Viewing the generated interactive HTML in the tab below, with a “View Preview” option that allows to toggle off the interactive buttons and view how the final HTML file looks like.

- Modify the Background Color and Foreground Color for every element in the generated HTML. Additionally, the tool also provides “presets” for setting this properties. The color properties for the presets are based off of [17].

- Modifying the randomly generated text for every text field in the webpage.

- Modifying the images present in the webpage

- Downloading the modified HTML along with its corresponding CSS, Javascript and images as a complete zip, so that it can e used in other downstream tasks.

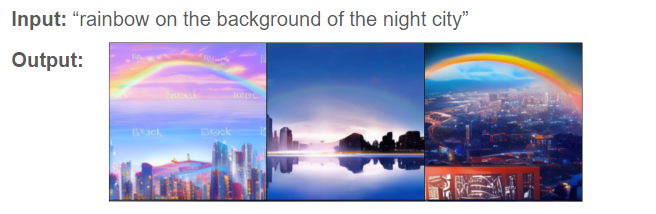

We also make a note of the GAN used to allow custom image generation for the various image components on the webpage. If the webpage contains a image component, the user can either select and upload an image or input a text and generate images using a GAN. We have leveraged an existing text-to-image generation GAN (Ru-Dalle[14]), with an emphasis on response time. Figure 11 demonstrates a sample output of text-to-image generation using the GAN.

Fig 11. Sample ru-Dalle GAN output

Results

In this section , we describe the results of the overall project. We begin with a quantitaive analysis on the project, and follow this up by demonstrating some qualitative results.

Quantitative Analysis

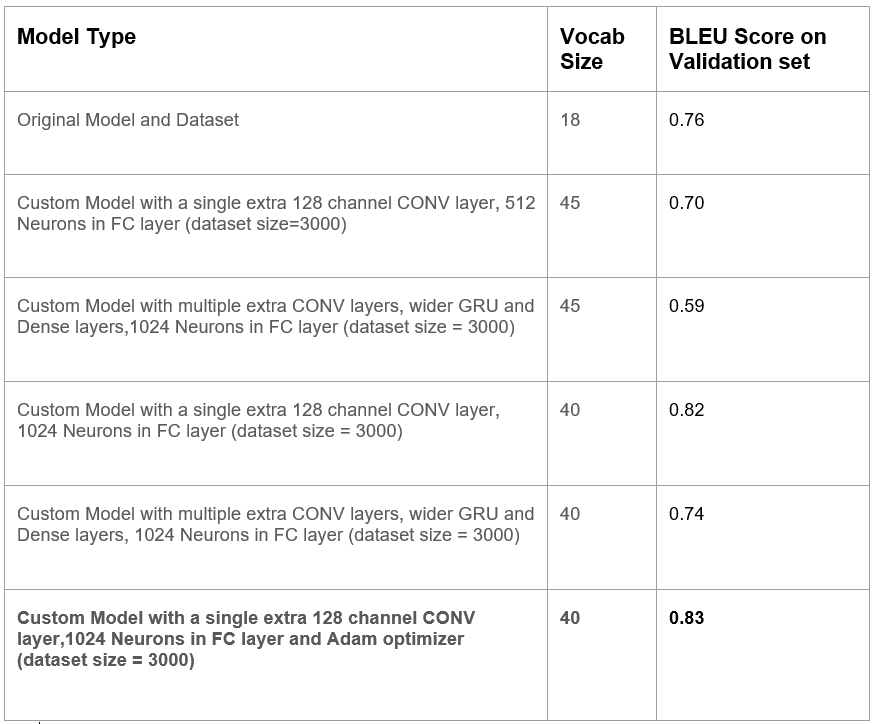

The model is evaluated using the BLEU score[16]. This is a typical statistic used in machine translation projects to determine how closely a machine-generated text resembles what a person would have produced given the identical input. To construct a modified version of precision, the BLEU analyses n-gram sequences from both the created and reference text. The measure serves as an ideal metric for this project because it takes into account the actual items in the output HTML, as well as their relative positions. Table 1 demonstrates the demonstrates the evolution of the evaluation metric, BLEU score, across various model attempts.

Table 1. BLEU score evolution across experiments

As we see from the above table, our best performing model, which is utilised by the tool,is able to generate an overal BLEU score of 0.83 on the validation set. While we acknowledge that this cannot be directly compared against the 0.82 BLEU score of [3] on its dataset, the metric helps us to determine our improved performance on a far more diverse dataset as opposed to [3], which demonstrates better model robsutness.

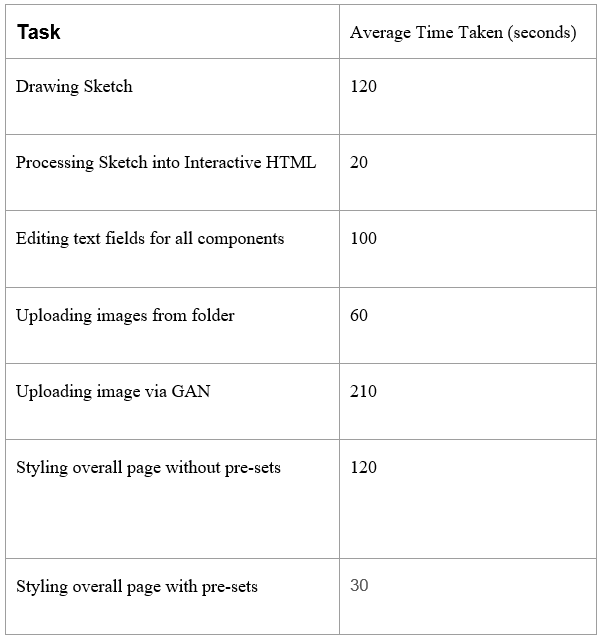

We also perform a timing analysis as shown in Table 2. The average values were obtained based on multiple attempts made by the two contributors to this project, to try and develop an overall webpage from a sketch. From the table , we notice that on average, it could take about 6 minutes to completely generate a stylised HTML page from a sketch, with a worst case of about 12 minutes for even more complex sketches. This toy example thus demonstrates the potential of developing such a "no-code" application.

Table 2. Timing analysis done based on the 2 project contributors

Qualitative Analysis

In this section we demonstrate certain qualitative results for our project. Figures 12 and 13 demonstrates several use cases where our model was able to succesfully predict the individual components. It also demonstrates the output post various styling modifications to demonstrate the flexibility in obtaining output with the proposed tool.

Figure 12. Demo outputs for successful cases. Top: Sketch, Middle: Interactive HTML, Bottom: Sample Stylised HTML

Figure 13. Some other sample outputs

As we see from these results, the model is able to generate succesful outputs on several components. Moroever, we observe that despite there be no fixed position for these components, or no fixed presence or an of the components, the tool is still able to produce an accurate output. This demonstrates one of the improvements of the tool over [3], in its ability to generalise across random variations.

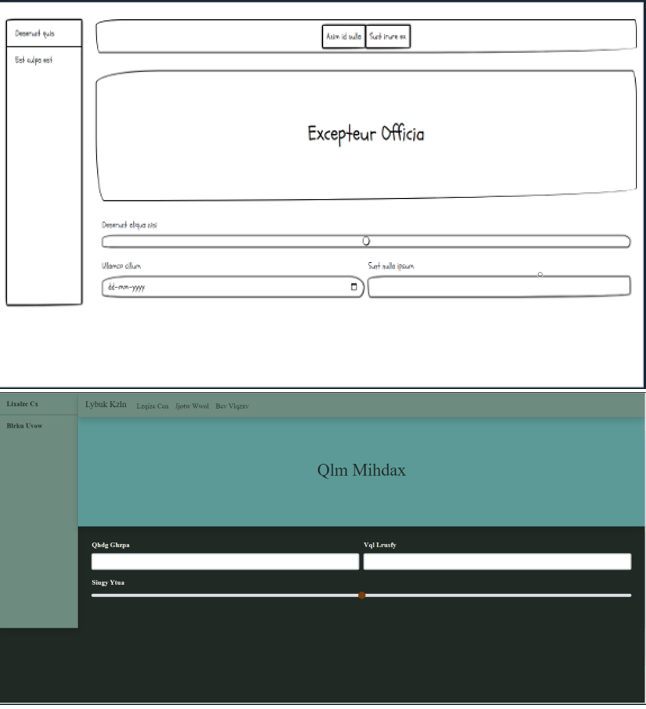

However, the model is not immune from errors. In Figure 14, we demonstrate a case where the model fails to make the exact prediction.

Figure 14. Sample Failure Case

As we can see, in these cases, the model was not able to differentiate between the individual components in the sketch accordingly. Based on a qualitative analysis, we identify two main situations where the mode sees a difficulty in making predictions:

- The model finds it difficult to distinguish between the “text”,”date” and “range” form components on the same form.

- The model finds it difficult to distinguish between “paragraph” and “list” components on the same form.

In both these cases, we notice a common aspect is that the model finds it difficult to distinguish between components that have very smal differntiate factors. The three form components look structurally similar to each others, with minute differences such as an extra icon. Similiarly, the paragraph and the list components look quite similar to each other barring minute differences such as numbers or bullets. This helps cement the analysis that one line of study towards improving this model would involve improving the image-encoder portion of the architecture, through methods such as using a deeper network, increasing the number of training samples and allowing for larger image inputs to the image-encoder model.

Conclusion and Future Work

In this project, we seek to develop an interactive human-centric tool that allows for any designer to create a HTML web-page within the span of few minutes. The tool provides a "no-code" approach towards developing HTML pages from hand-drawn sketches, while allowing for creative input and modifications. As demonstrated in the results, the tool was able to succesfully generate suitable outputs for the provided sketches, and provided a sizeable amount of modifying features to generate several variations of the webpage. Future lines of work for this project could involve further improving the performance and generalization of the model, generating more realistic UI by scraping actual websites for a train dataset, and ultimately realising the goal of generating web-pages without any visual cues from the user, through advanced tools such as Condtional GANs towards fully automated Webpage generation. The code can be found here

References

[1] Microsoft Corporation, Sketch2Code : https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/ai/ai-lab-sketch2code

[2] Tony Beltramelli. 2018. Pix2code: Generating Code from a Graphical User Interface Screenshot. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCHI Symposium on Engineering Interactive Computing Systems (EICS ‘18). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Article 3, 1–6. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3220134.3220135

[3] SketchCode, Ashwin Kumar, https://github.com/ashnkumar/sketch-code

[4] sketch2code, Anchen, https://github.com/mzbac/sketch2code

[5] Sketch2code using Visual Attention & LSTM Decoder, Vincent Kieuvongngam, https://vincentk1991.github.io/sketch2code/

[6] Google Material Design, https://material.io/

[7] Biplab Deka, Zifeng Huang, Chad Franzen, Joshua Hibschman, Daniel Afergan, Yang Li, Jeffrey Nichols, and Ranjitha Kumar. 2017. Rico: A Mobile App Dataset for Building Data-Driven Design Applications. In Proceedings of the 30th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST ‘17). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 845–854. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3126594.3126651

[8] Andrés Soto, Héctor Mora, Jaime A. Riascos,Web Generator: An open-source software for synthetic web-based user interface dataset generation,SoftwareX,Volume 17,2022,100985,ISSN 2352-7110,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.softx.2022.100985.

[9] Emil Wallner, https://blog.floydhub.com/turning-design-mockups-into-code-with-deep-learning/?source=techstories.org

[10] Sarah Suleri, Vinoth Pandian Sermuga Pandian, Svetlana Shishkovets, and Matthias Jarke. 2019. Eve: A Sketch-based Software Prototyping Workbench. In Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ‘19). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, Paper LBW1410, 1–6. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3290607.3312994

[11]Vinyals, Oriol & Toshev, Alexander & Bengio, Samy & Erhan, Dumitru. (2015). Show and tell: A neural image caption generator. 3156-3164. 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298935.

[12]Kyunghyun Cho, Bart van Merriënboer, Caglar Gulcehre, Dzmitry Bahdanau, Fethi Bougares, Holger Schwenk, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. Learning Phrase Representations using RNN Encoder–Decoder for Statistical Machine Translation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 1724–1734, Doha, Qatar. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[13]Simonyan, Karen and Zisserman, Andrew. “Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition.” CoRR abs/1409.1556 (2014)

[14]Sketch,https://www.sketch.com/

[15]Bubble,https://bubble.io/

[16]Kishore Papineni, Salim Roukos, Todd Ward, and Wei-Jing Zhu. 2002. BLEU: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th Annual Meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL ‘02). Association for Computational Linguistics, USA, 311–318. https://doi.org/10.3115/1073083.1073135

[17]http://colormind.io/bootstrap/