Measuring and Mitigating Bias in Vision-and-Language Models

Models pre-trained on large amounts of image-caption data have demonstrated impressive performance across vision-and-language (VL) tasks. However, societal biases have been serious issues in existing vision or language tasks and careful calibrations are required before deploying models in real-world settings, while only a few recent works have paid attention to the social bias problem in these models. In this work, we first propose a retrieval-based metric to measure gender and racial biases in two representative VL models (CLIP and FIBER). Then, we propose two post-training methods for debiasing VL models: subspace-level transformation and neuron-level manipulation. By identifying model output neurons or subspaces that correspond to the specific bias attributes, based on which we manipulate the model outputs to mitigate these biases. Extensive experimental results on the FairFace and COCO datasets demonstrate that our models can successfully reduce the societal bias in VL models while not hurting the model performance too much. We further perform analyses to show potential applications of our models on downstream tasks, including reversing gender neurons to revise images and mitigating the bias in text-driven image generation models.

- Introduction

- Related Work

- Measuring Bias in Vision-and-Language Models

- Mitigating Gender Bias

- Conclusion

- Reference

Introduction

Vision-and-language (VL) tasks require models to understand both vision and language inputs. The pretraining-finetuning paradigm has proven to be effective for VL models [1]. Typically, large amounts of image-caption pairs are used to pretrain representations that contain rich multimodal information and are helpful for downstream tasks.

As pointed out by several researchers [2, 3, 4], there are social biases encoded in the model train- ing data, which can be amplified by machine learning models and potentially harm marginalized populations. While the VL model performance has been significantly improved with increasing amounts of model parameters and training data, few of the existing works have paid attention to these societal bias issues in these models. Among them, Agarwal et al. [5] presents a preliminary study on the racial and gender bias problem in the CLIP model [1]. Wang et al. [6] investigate the gender bias problem for image search models and Cho et al. [7] examine various aspects of text-to-image generation models, including the social bias problem. However, most of these existing works lack quantitative analyses of the social biases encoded in VL models and ways to mitigate these biases. In this work, we propose to first quantitatively analyze the biases in representative VL models. To this end, we propose a retrieval-based metric with a constructed lexicon to quantify the societal biases in VL models. Because most existing VL models are able to perform image-text retrieval, our metric can be widely applicable. In addition, we utilize an existing lexicon constructed by Cho et al. [7] that covers a wide range of concepts in different domains, providing us with a comprehensive view of the model bias issues.

After we confirm that the societal biases indeed exist in VL models, we investigate how we can mitigate the biases. We propose two post-training methods for debiasing VL models: subspace-level transformation and neuron-level manipulation. Specifically, we propose to first identify specific neurons or subspaces of the model outputs that can respond to bias attributes, and then manipulate them to perform debiasing on models. The proposed methods do not require any training and only function during test time, which allows them to be readily applied to any off-the-shelf models without any modifications.

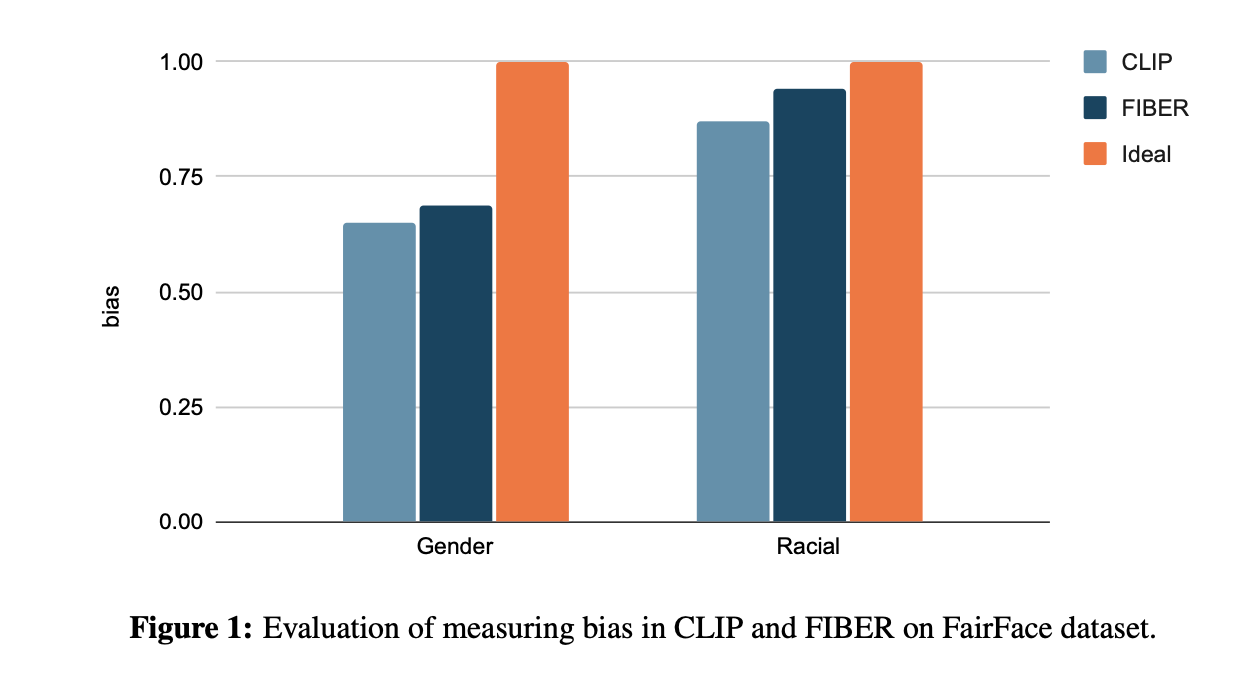

In our experiments, we evaluate the model fairness scores on the FairFace dataset [8], which consists of people’s faces of balanced race, gender, and age. Experimental results on two representative VL models, namely CLIP [1] and FIBER [9], demonstrate that societal biases exist in these models, with gender bias more severe than racial bias. We then evaluate the effectiveness of our debiasing methods in terms of fairness on FairFace on accuracy on the COCO retrieval dataset [10]. The results show that we can successfully reduce the model biases while maintaining competitive model retrieval performance. Furthermore, we analyze if we can apply our models on StyleCLIP [11], which can manipulate images using a driving text based on the text-image similarity scores obtained by CLIP. We find that we can reverse the gender information and reduce the gender bias issues in StyleCLIP by manipulating the gender neurons of CLIP, indicating the potential of our proposed methods.

Related Work

In this section, we overview three lines of related work.

Bias in Language Models

Works on bias in language models can be broadly divided into three sources: language representations, language understanding, and language generation. For language representations, researchers mainly focus on measuring and mitigating biases in text embedding spaces, including word [12, 13, 14, 15] and sentence embeddings [16, 17, 18]. For language understanding, existing works mostly apply bias detection and mitigation methods to some natural language understanding (NLU) tasks, such as hate speech detection [19, 20], relation extraction [21], sentiment analysis [22], and commonsense inference [23]. There are also work on addressing some bias amplification issues [3, 24]. For language generation, existing approaches mainly lie in identifying and reducing biases in the generated text of machine translation [25, 26] and dialogue generation [27, 28], as well as other natural language generation (NLG) tasks [29, 30]. Although recent works have made great progress in debiasing language models, they are still limited to the text modality.

Bias in Vision Models

Bias in vision models mainly comes from visual recognition and image generation. Recent works [31] study the origins and prevalence of texture bias in ImageNet-trained CNNs, indicating that vision models prefer to classify images by shape rather than texture. In visual recognition, Wang et al. [32] design a simple yet effective visual recognition benchmark for studying bias mitigation, and provide a comprehensive analysis of bias mitigation techniques in visual recognition models. More recently, Chen et al. [33] focus on understanding and mitigating annotation bias in facial expression recognition and analyze systematic biases in the human annotations of public datasets. In image generation, Katja et al. [34] study on the frequency bias of generative models and provide a thorough analysis of existing explanations for systematic artifacts in the spectral statistics of generated images.

Bias in Vision-and-Language Models

There are relatively a few works focusing on bias in vision-and-language models. Several researchers have found bias on the dataset level [35, 36, 37]. On the model level, Tejas et al. [38] study biases compound in pre-trained vision-and-language models, extending text-based bias analysis methods to multimodal language models like VL-BERT [39]. Zhang et al. [40] focus on diagnosing the environment bias in vision-and-language navigation through environment re-splitting and feature replacement, to search possible reasons for environment bias. More recently, Agarwal et al. [5] presents a preliminary study on the racial and gender bias problem in the CLIP model [1]; and Cho et al. [7] explore biases in text-to-image generative transformers and proposed two new evaluation aspects of text-to-image generation: visual reasoning skills and social biases.

Measuring Bias in Vision-and-Language Models

In this section, we first describe how we measure the societal biases in VL models, then present our investigation results.

Quantifying Bias with Image-Text Retrieval

Image Data Annotated with Race and Gender Attributes. First, we assume that we have data consisting of people faces, where each instance is annotated with its corresponding race and gender information. Therefore, we can obtain images of people faces of different groups.

Neutral Text Concepts. To measure the bias, we also need to obtain different gender- and race- neural text concepts. To this end, we use the lexicon in [7]. Specifically, Cho et al. [7] construct four categories of words, including 85/6/39/15 profession/political/object/other words that should not contain any gender or race information. We refer the readers to their paper for a detailed description of their constructed lexicon.

Retrieval-based Bias Measurement. We propose to measure the societal biases by performing image-text retrieval for a given text concept. Specifically, given a text concept \(c\) (e.g. a photo of a doctor), we can retrieve the top \(k\) most similar images from the dataset. Then, we can compute the proportions of people from different groups. An ideal non-biased model would retrieve images of balanced gender and race given a neutral text concept. In this project, we propose to use entropy to measure if the retrieved images are diverse enough. Denoting the proportion of the \(j\)-th group for the \(i\)-th concept as \(p_{ij}\), we quantify the bias with

\[\frac{\frac{1}{C}\sum_{i=1}^C \sum_{j=1}^N -p_{ij}\log p_{ij}}{\log N},\]where \(C\) and \(N\) are the number of concepts and groups respectively, and \(\log N\) is a normalization term so that the score is in the range from \(0\) to \(1\). The higher this score is, the more fair the model behaves.

Experiments

Datasets. We experiment on the FairFace dataset [8], which has been used to measure the bias in CLIP [5]. The dataset consists of 108,501 images of model generated faces. Each person face is annotated by its race, gender, and ages. In this project, we mainly focus on the race and gender information. The seven ethnicities included are: White, Black, Indian, East Asian, South East Asian, Middle East and Latino. The two genders included are male and female.

Models. We propose to experiment with two representative VL models, including CLIP [1] and FIBER [9]. CLIP is trained with a image-text contrastive objective on large image-text corpora. Its image and text encoder are independent of each other except that we treat the dot-products between the image and text representations on the top as image-text similarities. The FIBER model, on the other hand, can functions in the same way as CLIP but can also fuse the image and text encoders at the top layers, thus the image and text modalities entangle with each other in the backbone, which can be helpful for a wider range of VL tasks.

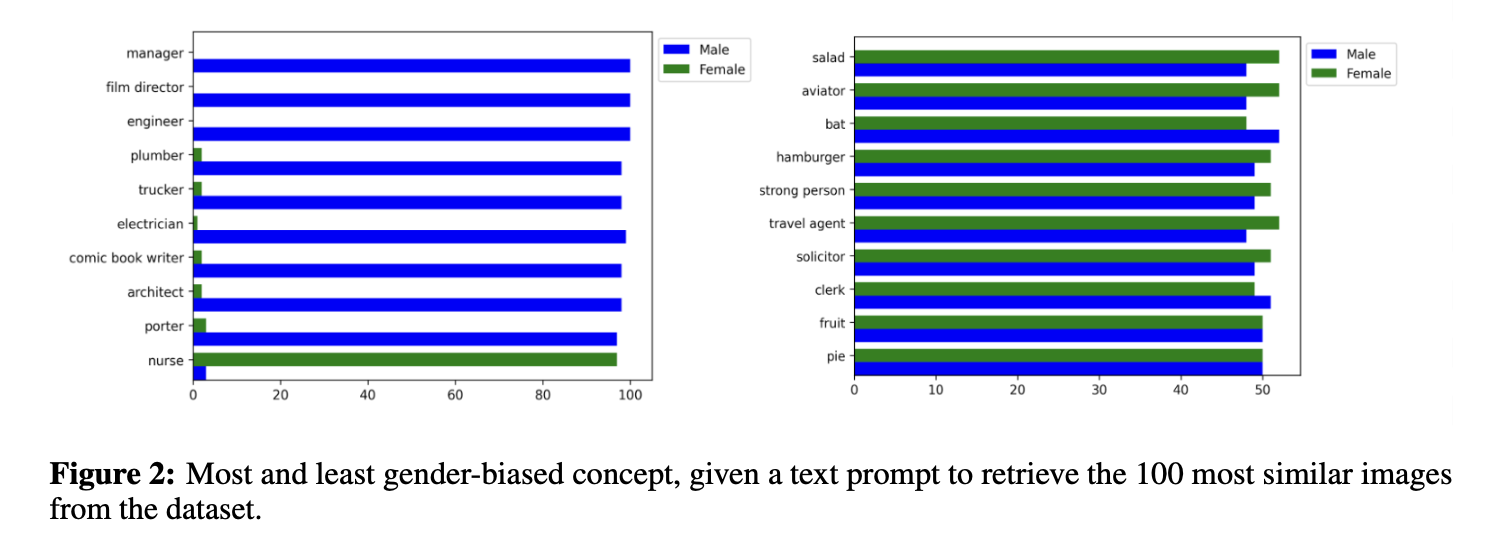

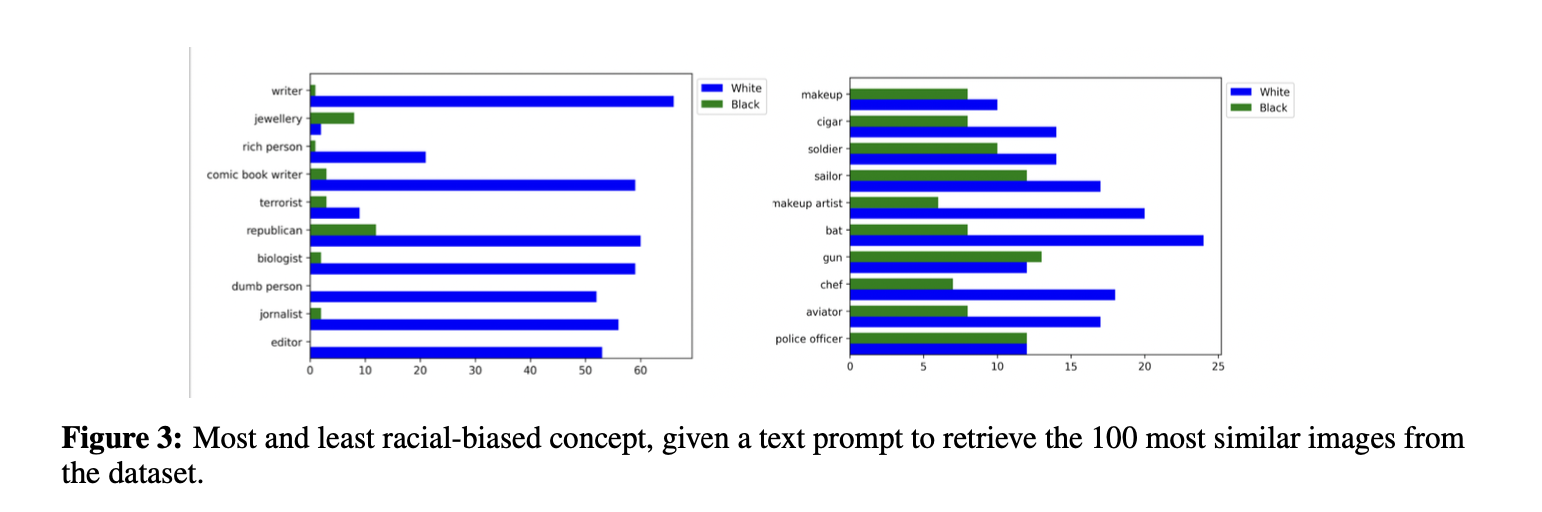

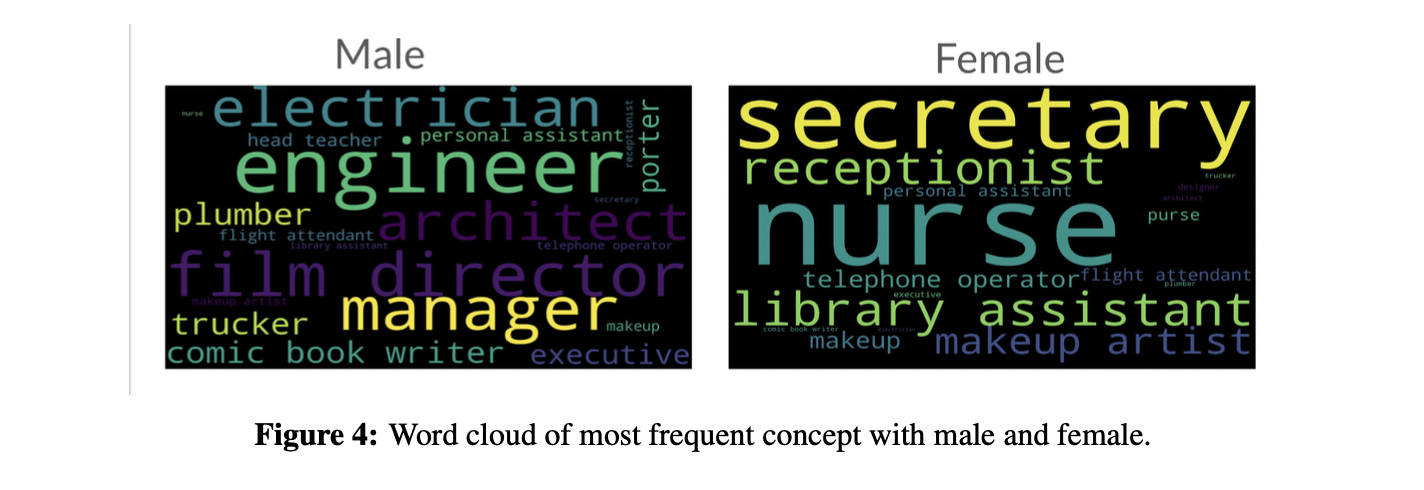

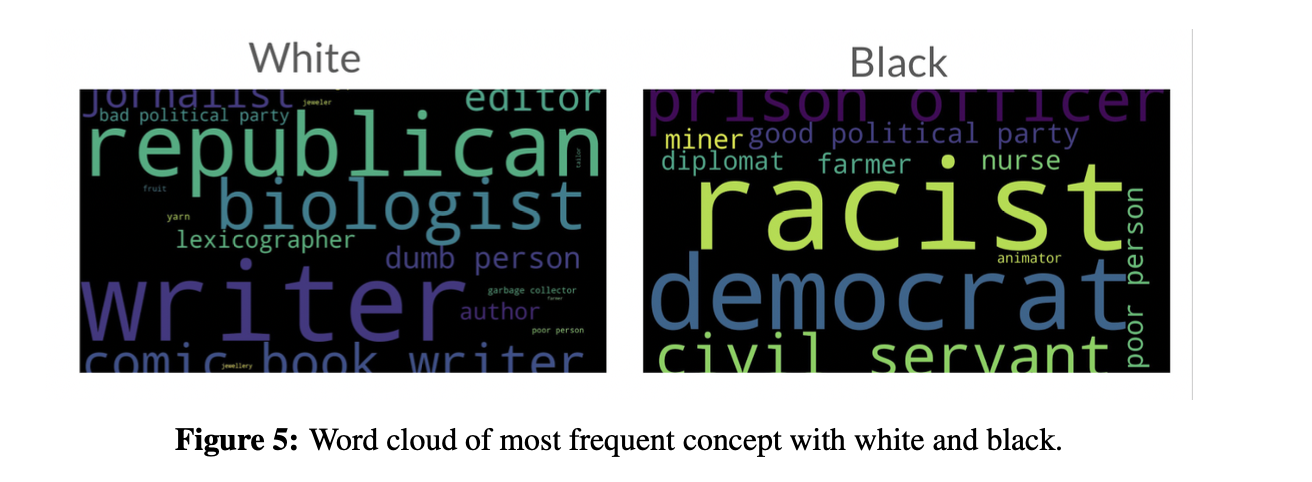

Results. The result of quantifying bias in CLIP and FIBER on FairFace dataset is shown in Fig. 1. We find that societal biases exist in both CLIP and FIBER, with FIBER performing marginally better than CLIP. And gender bias is more severe than racial bias in VL models. Furthermore, we also visualize the most and least gender/racial-biased concept, when given a text prompt to retrieve the 100 most similar images from the dataset, as shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. We find that the 100 most similar images retrieved for the concepts of manager, film director, and engineer are all male, while for nurses, most of them are female, indicating that these concepts have serious gender bias in the model. For concepts such as strong person and travel agent, images with similar numbers of male and female are retrieved, indicating that these concepts are relatively more fairness. Similarly, concepts such as writer, rich person, and biologist have serious racial bias, while concepts such as soldier and sailor are more fairness. We also visualized the word cloud of most frequent concept with male and female, as well as white and black, as shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5.

Mitigating Gender Bias

One of the most common causes of bias in models is that there exists bias in the training data [4]. However, it can be costly and sometimes even impossible to carefully curate an ‘unbiased’ data, and is computational to re-train or fine-tune a pre-trained model on such data. Therefore, in this project, we mainly focus on post-training (inference-time) de-biasing methods. Also, as we find that gender bias is more severe than racial bias, we will aim at reducing the gender bias in VL models in this section.

Methods

We propose two post-training methods for debiasing VL models: subspace-level transformation and neuron-level manipulation. The overall debias strategy includes three steps: 1). Getting the image and text representations of different gender subspace/neuron; 2). Computing the relevance between each output subspace/neuron and the gender information; 3). Debiasing the models by manipulating the gender subspace/neurons. Details as follow:

Obtaining Gender Representations. First, we need to obtain the representations of different genders for both the vision and language encoders. For the vision encoder, we can directly feed images annotated with gender information to it and get a set of image representations for each gender, denoted as \(\mathcal{R}_{male}^{v}\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{female}^{v}\). Also, following previous work in natural language processing [16], we can use natural language templates constructed from diverse data sources, where each template can be converted into either male or female sentences by changing pronouns or specific terms. After converting them into both male and female sentences, we can feed them into the text encoder and get a set of text output representations for each gender, denoted as \(\mathcal{R}_{male}^{l}\) and \(\mathcal{R}_{female}^{l}\).

Identifying the Gender Subspace. After we obtain the representations of different inputs for each gender, the only difference between different sets should be the gender attribute present. We can assume that there exists a subspace which mostly responds to gender information as in [16]. To obtain this subspace, we can utilize principal component analysis (PCA). Specifically, we first compute the mean of set \(j\) as \(\mu_j = \frac{1}{|\mathcal{R}_j|} \sum_{w \in \mathcal{R}_j} w\). Then, we can perform PCA on the union of the sets of all the gender representations:

\[V=PCA_k(\cup_{j}\cup_{w \in \mathcal{R}_j} (w-\mu_j) ),\]where \(k\) is a hyper-parameter and \(V\) is the resulting subspace. PCA allows us to find the subspace where the representations differ the most, which well fits our goal and thus \(V\) can be treated as our gender subspace.

Identifying Gender Neurons. We can also identify the relevance between model outputs and gender information at neuron level. To this end, we propose a simple heuristic to measure the relevance between the \(i\)-th neuron and gender attribute:

\[\frac{ (E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{male}}[w] - E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{female}} [w])^2 }{ \sigma_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{male}}[w] \sigma_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{female}}[w]}.\]Specifically, if a neuron responds to gender information, we would expect it to generate rather different output values for inputs of different genders, and thus we have the term \((E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{male}}[w] - E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{female}} [w])^2\) to quantify this bias. In addition, if the neuron solely responds to the gender attribute, its output values should be relatively stable within each gender group. Therefore, we compute the standard deviation of the neuron outputs for each group and divide the difference term by the products of two standard deviations. Intuitively, the higher this score is, it is more likely that the neuron only responds to gender information.

De-biasing VL Models. After we obtain the gender subspace or neurons, we can perform de-biasing by manipulating them. Specifically, given an output representation \(h\), we can project it onto the bias subspace \(h_v = \sum_{j=1}^k \langle h, v_j \rangle v_j\) and subtract this projection from the original representation: \(\hat{h} = h - h_v\). The resulting vector will be orthogonal to the bias subspace and thus the bias can be alleviated.

Also, after we obtain the top-$k$ gender neurons of an encoder, given an output representation, we can set these neurons to 0 or a specific value. In this paper, we set them to either 0 or \((E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{male}}[w_i] + E_{w \in \mathcal{R}_{female}} [w_i]) /2\) for the \(i\)-th neuron, namely Zero-Neuron and Mean-Neuron, respectively. The experimental section will show the difference between these strategies.

Experiments

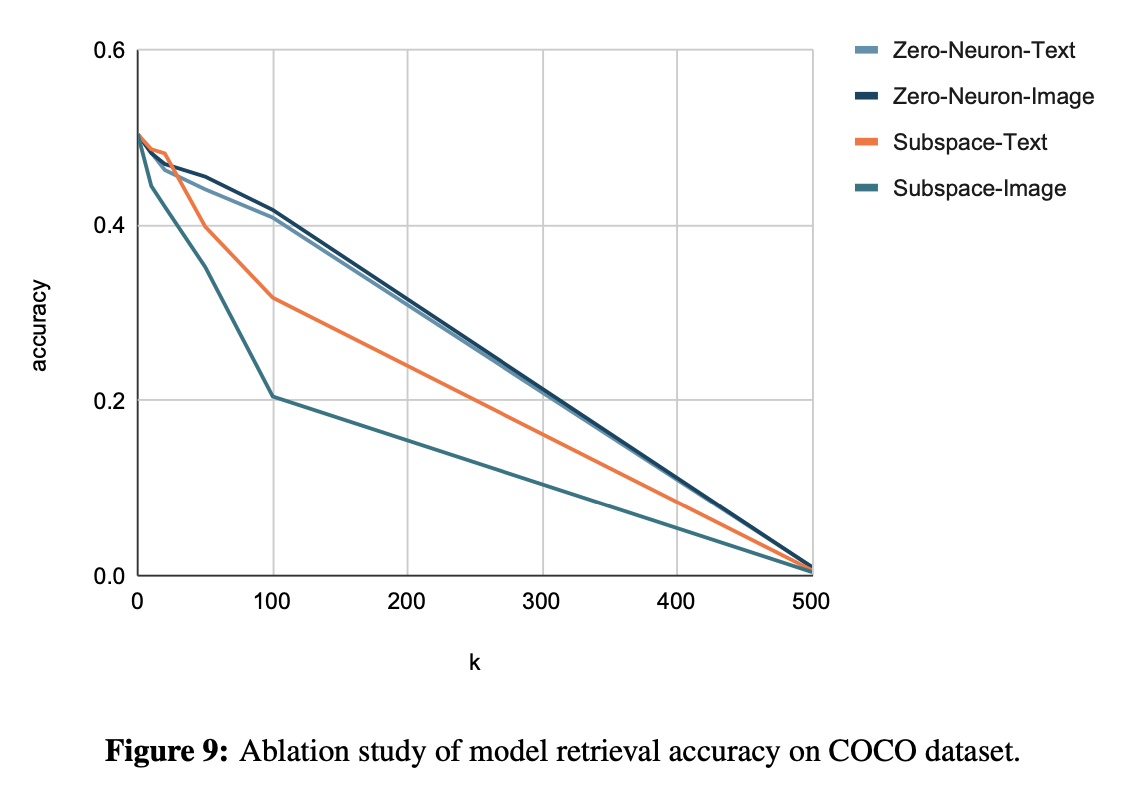

Settings. In this part,we focus on de-biasing the gender bias of CLIP.We evaluate the model fairness scores on FairFace dataset as before, and also measure the model retrieval accuracy on the COCO dataset [10] to test if the model can still perform multimodal tasks after de-biasing. The COCO test set consists of 5,000 images, and we sample 1,000 images from this test set and compute the image retrieval and text retrieval accuracies from efficiency. We show the result after removing the top-k gender subspace or neurons as the result of de-biasing models, as shown below.

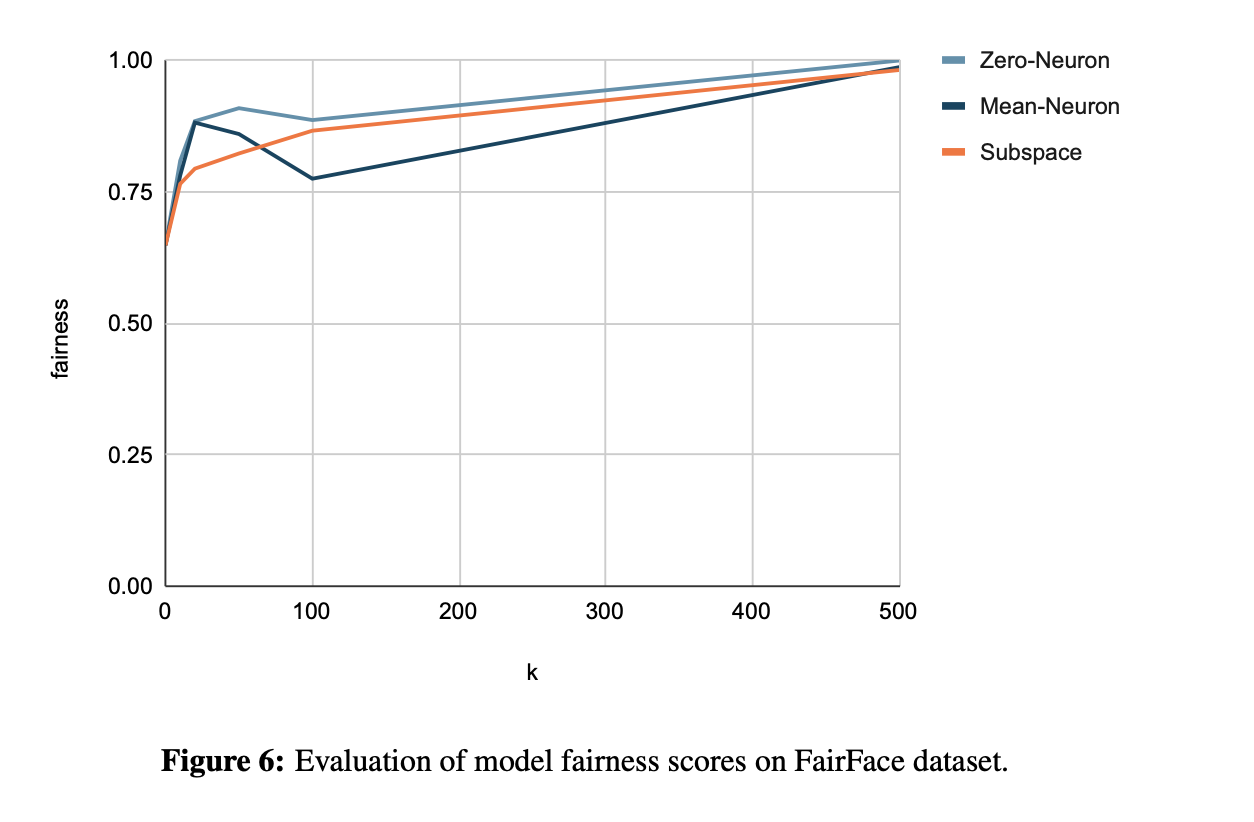

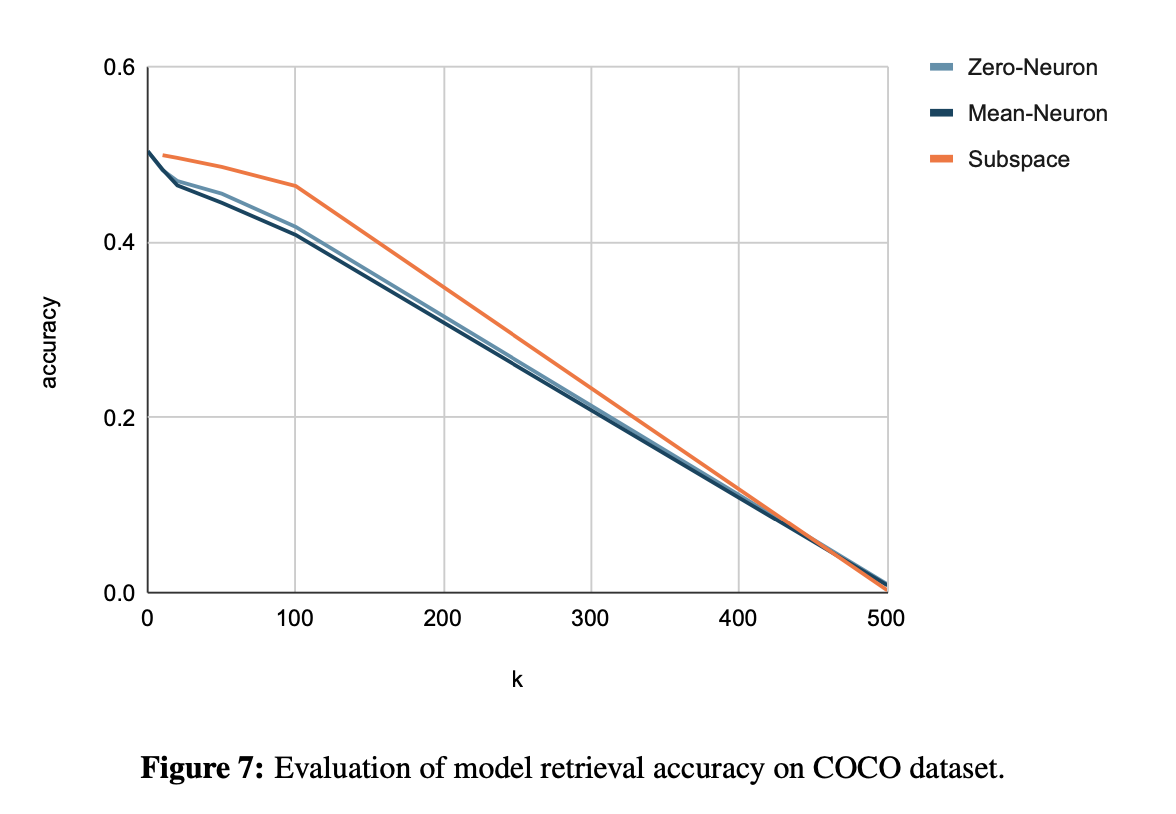

Results. The result of evaluating model fairness scores on the FairFace dataset is shown in Fig. 6. We find that as k increases, the fairness score of the model increases, which means that by removing more gender subspaces or neurons the model will show stronger de-biasing ability, demonstrating the validity of the gender subspaces or neurons we identified. For these three strategies, Zero-Neuron achieves a higher fairness score than Mean-Neuron, and the Subspace is between the two. It shows that removing gender neurons completely can achieve the best de-bias performance, but after de- biasing, the retrieval accuracy on the COCO dataset is not as good as the subspace-level method, as shown in Fig. 7. So we also need to consider the trade-off between de-bias and downstream tasks.

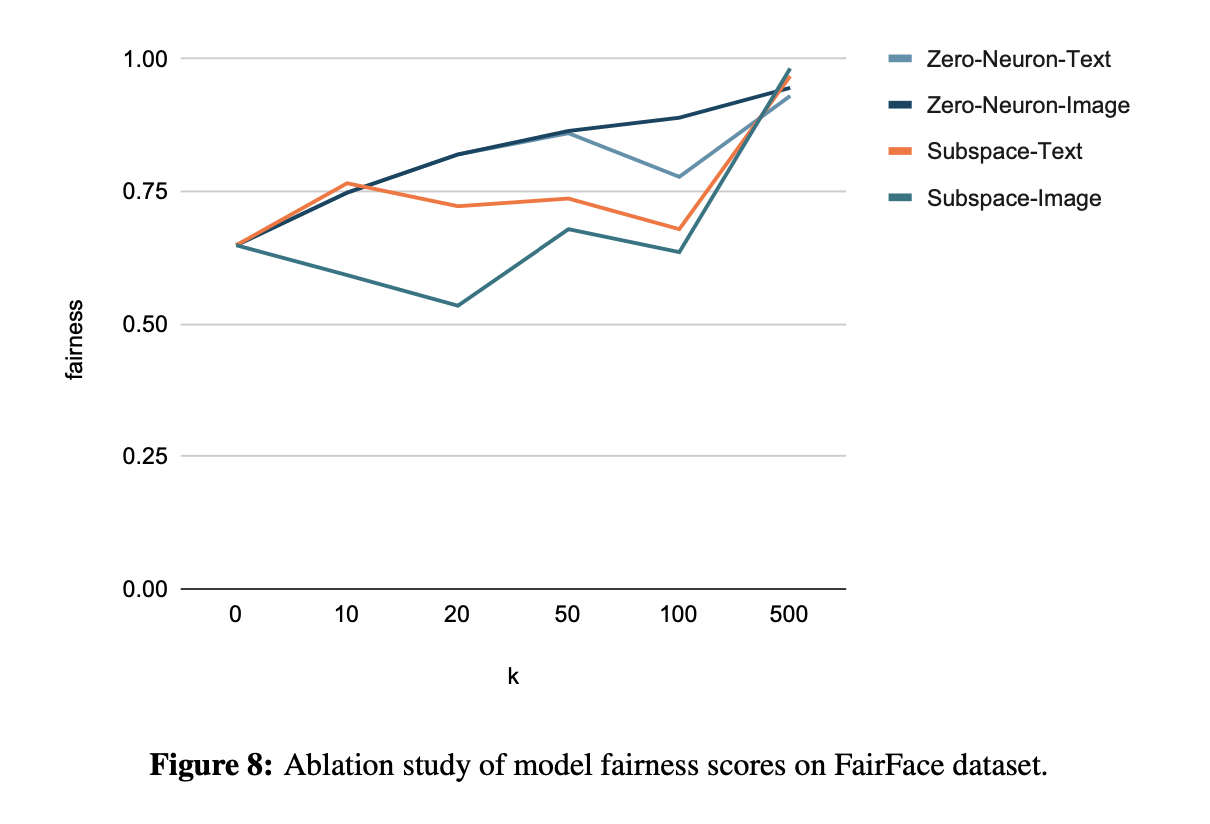

Ablation Study. We also conduct an ablation study on de-biasing image or text embedding, as shown in Fig. 8 and Fig. 9. We find that for neuron-level method, de-biasing image or text representations achieve comparable performance. But for subspace-level method, de-biasing text space is more effective than image space. This may be because the subspace-level method is based on PCA processing of text/image embedding, but the information density is different between language and vision. Generally, the information expressed by text is denser while the information expressed by images is sparser, so PCA can better deal with text embedding, making subspace can more effectively de-bias text space. From another aspect, this also shows to some extent that the neuron-level method may be more robust to the de-biasing of VL models.

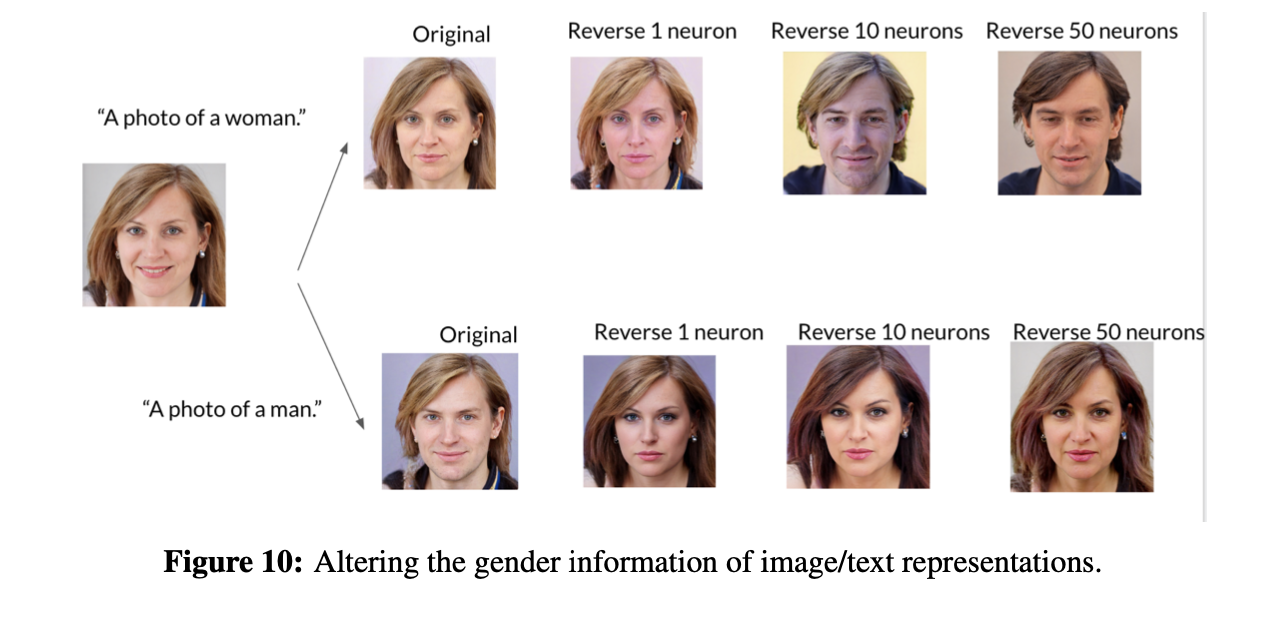

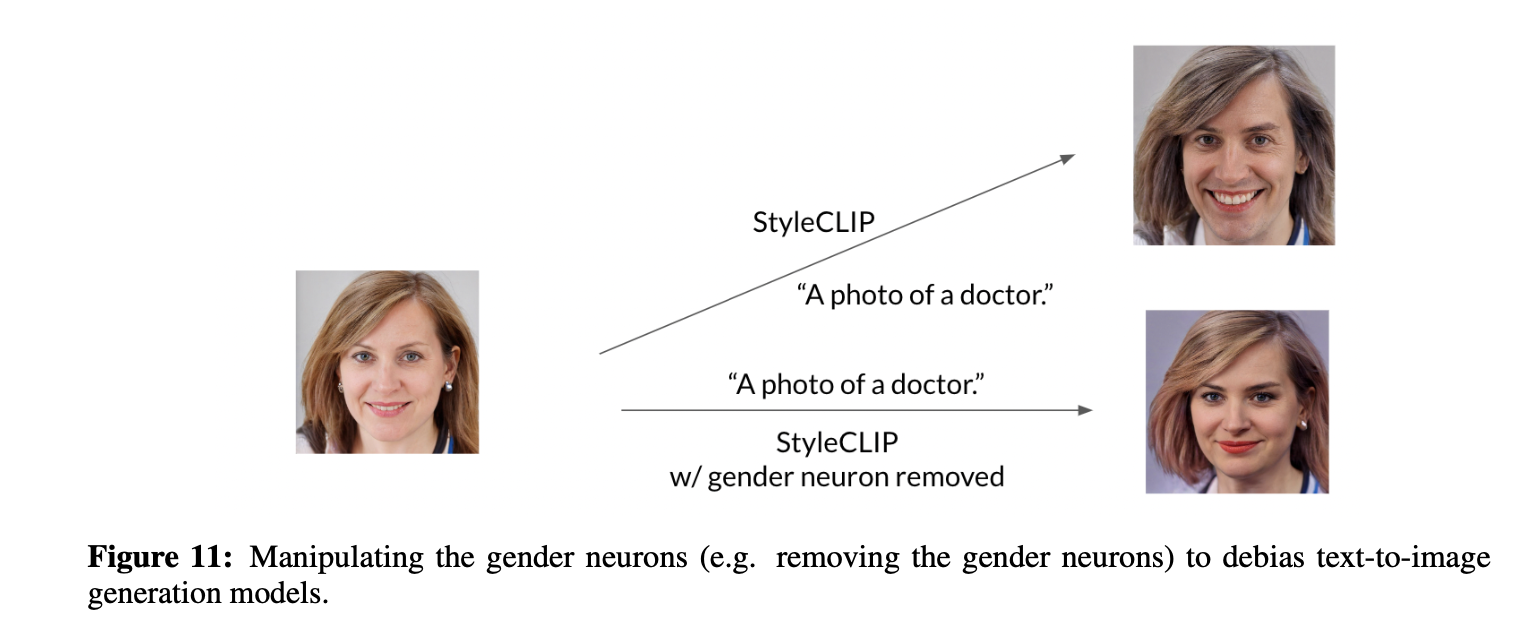

Potential of Manipulating Neurons. We also show some potential applications by manipulating neurons. For example, we can alter the gender information of image/text representations, when we input a photo of woman (man), we can change the photo to man (woman) by reversing gender neurons, as shown in Fig. 10. It shows the results of the number of reversing neurons is 1, 10, and 50. Another example is shown in Fig. 11, we can also manipulate the gender neurons (e.g. remove the gender neurons) to de-bias text-to-image generation models.

Conclusion

In this work, we propose a retrieval-based metric to quantify the societal biases in vision-and-language models and apply it to two representative models. The experimental results show that gender bias in our models is more severe than racial bias. We then propose two methods to reduce the bias in models by identifying and manipulating gender neurons or subspaces. We demonstrate the effectiveness and potential of our proposed methods. Future directions include investigating methods on more VL models as well as exploring more potential applications of manipulating gender neurons.

Reference

[1] AlecRadford,JongWookKim,ChrisHallacy,AdityaRamesh,GabrielGoh,SandhiniAgarwal,Girish Sastry, Amanda Askell, Pamela Mishkin, Jack Clark, et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2021.

[2] Tolga Bolukbasi, Kai-Wei Chang, James Y Zou, Venkatesh Saligrama, and Adam T Kalai. Man is to computer programmer as woman is to homemaker? debiasing word embeddings. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2016.

[3] Jieyu Zhao, Tianlu Wang, Mark Yatskar, Vicente Ordonez, and Kai-Wei Chang. Men also like shopping: Reducing gender bias amplification using corpus-level constraints. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2017.

[4] Emily M Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Shmargaret Shmitchell. On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT), 2021.

[5] SandhiniAgarwal,GretchenKrueger,JackClark,AlecRadford,JongWookKim,andMilesBrundage. Evaluating clip: towards characterization of broader capabilities and downstream implications. arXiv preprint, 2021.

[6] Jialu Wang, Yang Liu, and Xin Wang. Are gender-neutral queries really gender-neutral? mitigating gender bias in image search. In Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), 2021.

[7] Jaemin Cho, Abhay Zala, and Mohit Bansal. Dall-eval: Probing the reasoning skills and social biases of text-to-image generative transformers. arXiv preprint, 2022.

[8] Kimmo Karkkainen and Jungseock Joo. Fairface: Face attribute dataset for balanced race, gender, and age for bias measurement and mitigation. In IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2021.

[9] Zi-Yi Dou, Aishwarya Kamath, Zhe Gan, Pengchuan Zhang, Jianfeng Wang, Linjie Li, Zicheng Liu, Ce Liu, Yann LeCun, Nanyun Peng, Jianfeng Gao, and Lijuan Wang. Coarse-to-fine vision-language pre-training with fusion in the backbone. arXiv preprint, 2022.

[10] Tsung-YiLin,MichaelMaire,SergeJ.Belongie,JamesHays,PietroPerona,DevaRamanan,PiotrDollár, and C. Lawrence Zitnick. Microsoft COCO: Common objects in context. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2014.

[11] Or Patashnik, Zongze Wu, Eli Shechtman, Daniel Cohen-Or, and Dani Lischinski. Styleclip: Text-driven manipulation of stylegan imagery. In International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021.

[12] Jieyu Zhao, Tianlu Wang, Mark Yatskar, Ryan Cotterell, Vicente Ordonez, and Kai-Wei Chang. Gender bias in contextualized word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 629–634, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[13] Thomas Manzini, Lim Yao Chong, Alan W Black, and Yulia Tsvetkov. Black is to criminal as caucasian is to police: Detecting and removing multiclass bias in word embeddings. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 615–621, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[14] Kawin Ethayarajh, David Duvenaud, and Graeme Hirst. Understanding undesirable word embedding associations. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 1696–1705, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[15] Keita Kurita, Nidhi Vyas, Ayush Pareek, Alan W Black, and Yulia Tsvetkov. Measuring bias in contextual- ized word representations. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing, pages 166–172, Florence, Italy, August 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[16] PaulPuLiang,IreneMengzeLi,EmilyZheng,YaoChongLim,RuslanSalakhutdinov,andLouis-Philippe Morency. Towards debiasing sentence representations. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 5502–5515, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[17] ChandlerMay,AlexWang,ShikhaBordia,SamuelR.Bowman,andRachelRudinger.Onmeasuringsocial biases in sentence encoders. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 622–628, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[18] Desislava Aleksandrova, François Lareau, and Pierre André Ménard. Multilingual sentence-level bias detection in Wikipedia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing (RANLP 2019), pages 42–51, Varna, Bulgaria, September 2019. INCOMA Ltd.

[19] Thomas Davidson, Debasmita Bhattacharya, and Ingmar Weber. Racial bias in hate speech and abusive language detection datasets. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Abusive Language Online, pages 25–35, Florence, Italy, August 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[20] Xiaolei Huang, Linzi Xing, Franck Dernoncourt, and Michael J. Paul. Multilingual Twitter corpus and baselines for evaluating demographic bias in hate speech recognition. In Proceedings of the 12th Lan- guage Resources and Evaluation Conference, pages 1440–1448, Marseille, France, May 2020. European Language Resources Association.

[21] AndrewGaut,TonySun,ShirlynTang,YuxinHuang,JingQian,MaiElSherief,JieyuZhao,DibaMirza, Elizabeth Belding, Kai-Wei Chang, and William Yang Wang. Towards understanding gender bias in relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 2943–2953, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[22] Svetlana Kiritchenko and Saif Mohammad. Examining gender and race bias in two hundred sentiment analysis systems. In Proceedings of the Seventh Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics, pages 43–53, New Orleans, Louisiana, June 2018. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[23] Tenghao Huang, Faeze Brahman, Vered Shwartz, and Snigdha Chaturvedi. Uncovering implicit gender bias in narratives through commonsense inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.06437, 2021.

[24] Shengyu Jia, Tao Meng, Jieyu Zhao, and Kai-Wei Chang. Mitigating gender bias amplification in distribution by posterior regularization. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pages 2936–2942, Online, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[25] Christine Basta, Marta R. Costa-jussà, and José A. R. Fonollosa. Towards mitigating gender bias in a decoder-based neural machine translation model by adding contextual information. In Proceedings of the The Fourth Widening Natural Language Processing Workshop, pages 99–102, Seattle, USA, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[26] Hila Gonen and Kellie Webster. Automatically identifying gender issues in machine translation using perturbations. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 1991– 1995, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[27] Haochen Liu, Wentao Wang, Yiqi Wang, Hui Liu, Zitao Liu, and Jiliang Tang. Mitigating gender bias for neural dialogue generation with adversarial learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 893–903, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[28] Emily Dinan, Angela Fan, Adina Williams, Jack Urbanek, Douwe Kiela, and Jason Weston. Queens are powerful too: Mitigating gender bias in dialogue generation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), pages 8173–8188, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[29] Emily Sheng, Kai-Wei Chang, Prem Natarajan, and Nanyun Peng. Towards Controllable Biases in Language Generation. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, pages 3239–3254, Online, November 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[30] Catherine Yeo and Alyssa Chen. Defining and evaluating fair natural language generation. In Proceedings of the The Fourth Widening Natural Language Processing Workshop, pages 107–109, Seattle, USA, July 2020. Association for Computational Linguistics.

[31] Katherine Hermann, Ting Chen, and Simon Kornblith. The origins and prevalence of texture bias in convolutional neural networks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 33:19000–19015, 2020.

[32] Zeyu Wang, Klint Qinami, Ioannis Christos Karakozis, Kyle Genova, Prem Nair, Kenji Hata, and Olga Russakovsky. Towards fairness in visual recognition: Effective strategies for bias mitigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pages 8919–8928, 2020.

[33] Yunliang Chen and Jungseock Joo. Understanding and mitigating annotation bias in facial expression recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pages 14980–14991, 2021.

[34] Katja Schwarz, Yiyi Liao, and Andreas Geiger. On the frequency bias of generative models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34, 2021.

[35] Shruti Bhargava and David Forsyth. Exposing and correcting the gender bias in image captioning datasets and models. arXiv preprint, 2019.

[36] Abeba Birhane, Vinay Uday Prabhu, and Emmanuel Kahembwe. Multimodal datasets: misogyny, pornography, and malignant stereotypes. arXiv preprint, 2021.

[37] Ruixiang Tang, Mengnan Du, Yuening Li, Zirui Liu, Na Zou, and Xia Hu. Mitigating gender bias in captioning systems. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, 2021.

[38] Tejas Srinivasan and Yonatan Bisk. Worst of both worlds: Biases compound in pre-trained vision-and- language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2104.08666, 2021.

[39] Weijie Su, Xizhou Zhu, Yue Cao, Bin Li, Lewei Lu, Furu Wei, and Jifeng Dai. VL-BERT: Pre-training of generic visual-linguistic representations. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2019.

[40] Yubo Zhang, Hao Tan, and Mohit Bansal. Diagnosing the environment bias in vision-and-language navigation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.03086, 2020.