VQPy

Video analytics has been gaining popularity in recent years, due to easier production of videos as well as development in computer vision algorithms and computing hardware. Traditional video analytics pipelines require developers to spend a lot of time on model optimizations, and can be difficult to reuse. Efforts such as SQL-like languages have tried to approach this problem, but only solved part of it, due to restrictions such as limited expressiveness. We propose to implement a Python dialect called VQPy, as an attempt to make video queries easier even for people with no CV-related knowledge, with flexible and customizable interfaces, and transparent query optimizations.

Introduction

Video analytics applications have been ubiquitous nowadays. Millions of cameras are recording around the world, and diverse analytics programs are running in the background to achieve different functionalities. For example, speeding vehicles can be automatically detected from road surveillance videos, and the administration staff can send speeding tickets to vehicle owners based on the number badge; fall detection can recognize people potentially falling, so medical professionals can take earliest actions to prevent injuries [1]; also, train stations and airports can utilize video analytics to find unattended luggages for travelers [2].

A video analytics application usually includes several different tasks organized in a certain order. Take speeding detection as example, it needs object detection to recognize vehicles and badges, uses object tracking to track speed of the vehicles, and utilize text recognition to identify badge numbers based on badge images. Most of the individual tasks are achieved by trained deep learning models, which heavily use tensor computation. And some components may also involve application-specific logics, implemented by general-purpose languages.

Python has become a de facto standard language to develop video analytics application. Its high-level semantics and dynamic features help to easily build prototypes by “gluing” different components. More importantly, the whole ecosystem of deep learning built upon Python, which means there are plenty of Python libraries as low hanging fruits.

The flexibility of Python gives users freedom to write code based on their own preference. However, given the lack of certain language standard and constraints, these applications can expose various forms of interfaces of modules, which compromises reusability. It is usually requires export knowledge to fully understand a standalone Python module, before integration. And even worse, when certain modules require replacement, for example, upgrade to new framework version or use more recent deep learning models, the Python code that gluing these components may need be rewritten.

There are some efforts that tries to improve the reusability of Python-based video analytics application. One of the typical examples are FrameQL [3]. FrameQL treats camera frames as relation tables, and allows users to use SQL-like syntax to query frames which satisfy certain conditions. An example of query written in FrameQL is shown below.

SELECT FCOUNT(*)

FROM taipei

WHERE class = 'car'

FrameQL does support some degree of modularity and reusability. Complex queries can be constructed with simple queries. Also, it relieves the burden of users to understand the implementation details. Instead, the user simply declare its goal. All procedures to select and generate the model pipeline is done by the SQL executor. Various optimizations can be made in the background for optimal performance.

However, SQL-like languages come with limited expressiveness. When these languages treats different frames in a video as different records in a relation table, it is easy to query information on each frame, but is much harder to express queries which needs information from different frames, such as tracking an object. Moreover, it is hard to support customization, as FrameQL only provides several pre-defined properties and limited interface to user-defined functions.

Language Design

The motivation of VQPy is to get the benefits of declarative language, including reusability and performance, but still provide a Python-like syntax for users to write code in a flexible way. A straw-man approach would be use the a python wrapper around FrameQL. For example, we can provide a few Python class including VObj for objects of interest on each frame, with a few properties, such as cls for object class and feature for the feature vector output by the object detection method.

class VObj:

def __init__():

self.timestamp: float

self.cls: str

self.trackid: str

self.mask: List[Tuple[float,float]]

self.features: List[float]

class Frame:

def objs() -> VObj: ...

We can provide a frame-based API for user to define the query. The equivalent Python code for the above FrameQL example is shown below. In this manner, we hide the details of object detector and provide user with a high-level properties to manipulate. Note as this is Python, so we can use all the syntax sugars to simplify our code, but here we only show a long version for explanation.

class Query:

def __call__(frame: Frame) -> int: ...

count = 0

for obj in frame.objs():

if obj.cls == 'car':

count += 1

return count

video = Video('taipei')

count = 0

for result in Query(video):

count += result

result = count / len(video)

This Python snippet is much more intuitive for user to understand and debug, especially model developer and data scientist, who heavily use Python, compared against SQL. We can also let user to easily use self-defined functions. In this example, the user defines a color function to get the color of an object and uses dynamic binding to bind color as a property member of VObj to make the code more consistent.

def color(obj: VObj) -> str: ...

VObj.color = property(lambda self: color(self))

class Query:

def __call__(frame: Frame) -> int: ...

count = 0

for obj in frame.objs():

if obj.cls == 'car' and obj.color == 'red':

count += 1

return count

So far, we only covered properties from a single frame. Cross-frame properties are also commonly seen, such as speed. To support cross-frame property, we need a object tracker to decide which detected objects on different frames belong to the same entity. From the abstraction level, we need a stateful context to save cross-frame variables. Following is an example design, where we save centers of the same entity in a context using a stateful decorator.

import numpy as np

class VObj:

def __init__():

self.center: Tuple[float,float] # center coordinate of bounding box

@stateful(centers)

def speed(obj: VObj) -> float:

centers.append(obj.center)

return np.linalg.norm(np.array(obj.center) - np.array(centers[-1]))

VObj.speed = property(lambda self: speed(self))

Structural Binding

This Python-based design achieves all features of FrameQL, and even go further for user-defined cross-frame properties. But it is still far from our goal. For example, what if user want to use a sequence of frames to calculate object’s speed. This is common demands, especially for sequential models. Following the same principle by not letting user rewrite any query logic, we should not let user to write a special snippet of code to “glue” these sequential models. Instead, we want to develop a method similar to how we use dynamic binding for simple properties.

The proposed solution is called “structural binding”. As shown in the following example, we bind the speeds function to all members of a sequence of VObj from a iterator. The way to understand this special syntax should be build an iterator of all VObj cross frames but belong to the same entity and use this iterator as argument for function speeds.

def speeds(objs: Iterator[VObj]) -> Iterator[float]:

center = []

for obj in objs:

...

Iterator[VObj.speed] = property(lambda self: speeds(self))

This feature is actually quite powerful. First of all, we open the space for users to write a wide spectrum of self-defined cross-frame properties, some may even include retrospective patterns [4]. Moreover, users don’t need to make single line of code change for speed property in query specification. And finally, users can switch between stateful context and structural binding, to meet their needs to integrate models with different interfaces.

Note structural binding syntax is not valid in Python. To simplify our implementation, we could also use system-level mapping to manage these bindings.

from vqpy import bindings

bindings['Iterator[VObj.speed]'] = property(lambda self: speeds(self))

One more thing to notice is that structural binding assumes that all frames should be ready for read. This is a safe assumption for offline applications such as video database. However, it is unsafe for online applications with streaming data.

Method Interception

Right now, we only discussed about user-defined properties. There are certain amount of “default” behaviors of this query, including the objection detection and tracking. It could happen that users want to bring their own object detector and tracker.

Using the idea of dynamic binding as an “interception” to existing methods, we can provide some known methods for users to bind. For example, (multiple) object tracker depends on a predicate that whether two objects on different frames are actually the same, which should have a type VObj, VObj -> bool. So users can bind a function with the same type to intercept the object tracker, using their own feature and distance functions:

from model import feature, distance

def match(a: VObj, b: VObj) -> bool:

return distance(feature(a), feature(b)) < 0.1

VObj.__eq__ = match

If we combine the idea with structural binding, we can also various other interfaces, such as an interface for Hungarian matching algorithm:

def match(a: List[VObj], b: List[VObj]) -> List[List[bool]]: ...

bindings['__match(List[VObj], List[VObj]) -> List[List[bool]]'] = match

Note we define this binding in a quite different way, by specifying the symbol of match function and its type. How to design a more unified binding expression is still a open question in project.

Query Optimization

It is obvious that tha above Python query imposes a high computational complexity, including a nested loop, first on all frames and another one of all objects on a frame. For standard video in 1080p and 30fps, this complexity is unacceptable. To get better performance without any code change, we aim to leverage programming language techniques, including code analysis and generation.

One of the most important optimizations for video data is frame filtering - instead of running an expensive object detection model on every frame, we only run it on dominant frames, which show distinguishable differences along neighboring frames, which could lead to different query results. The succeeding question is how to select dominant frames. We uses the method proposed in Reducto [5] to make the decision. Our frame-based query interface actually abstract user away from the access to individual frame. So we can potentially skip some frames without breaking the any assumption provided by language. This observation still hold for stateful context and structural binding.

Frame filtering helps to solve the complexity of the outer loop, for the inner loop, we can use dynamic batching [6]. The idea to batch a bundle of objects into a model for inference, which can better leverage the parallel computation units on accelerators. To transparently use dynamic batching, we need code analysis for the frame.objs loop. Specially, we need a control flow graph of all objects inside this loop and batch the objects in the path together. Note stateful context and structural binding is orthogonal to this optimization, as they only deal with cross-frame VObj of the same entity.

Evaluation

In this section, we will mainly evaluate the performance of VQPy.

These query optimizations mentioned above require a soruce-to-source compiler, with basci code analysis and generation functionalities. We use Python’s AST as our intermediate representation. Python’s ast library is our starting point. We also use code from pasta for code generation and mypy for type checking.

We chose 3 applications:

- Turning violation: detect vehicles that make turn when there are pedestrians crossing

- Speeding ticket: show license plate of speeding vehicle

- Fall detection: alarm when people fall to the ground

For turning violation and speeding ticket, we use Jackson Hole live stream. For speeding ticket , we use Newark live stream. Figure 1 shows a snapshot of these two videos. For fall detection, we use fall-up dataset.

Figure 1. Jackson Hole and Newark stream

And we use following models:

- YOLOX for object detection

- ByteTracker for object tracking

- HybridNets for lane detection, used in turning violation

- LPRNet for license plate recognition, used in speeding ticket

- KeypointRCNN for human post estimation, used in elderly fall detection

All our experiments are running on AWS g4dn.2xlarge, with 16 cores, 64 GB memory, and one Nvidia T4 GPU. We use the overall query runtime spend on the our video clips as the metric.

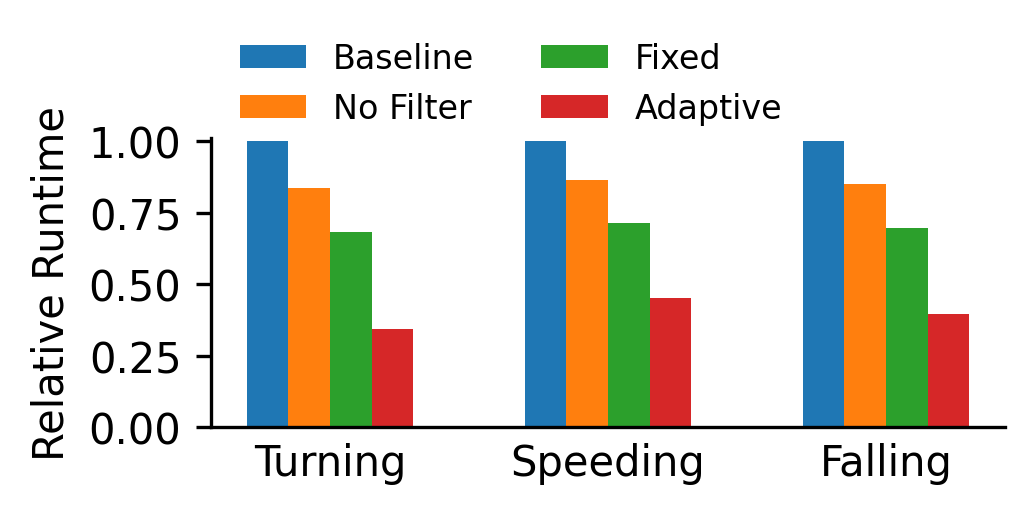

Figure 2 shows the performance comparison with various filtering methods. “No Filtering” means we don’t filter any frame. The performance gain comes from a optimized tracking implementation. “Fixed” means fixed threshold filtering. We choose the lowest frame rate without changing 90% of query results. “Adaptive” is the Reducto [5] style filtering, where we use offline profiling to determine the best threshold selection policy.

Figure 2. Runtime performance comparison with frame filtering

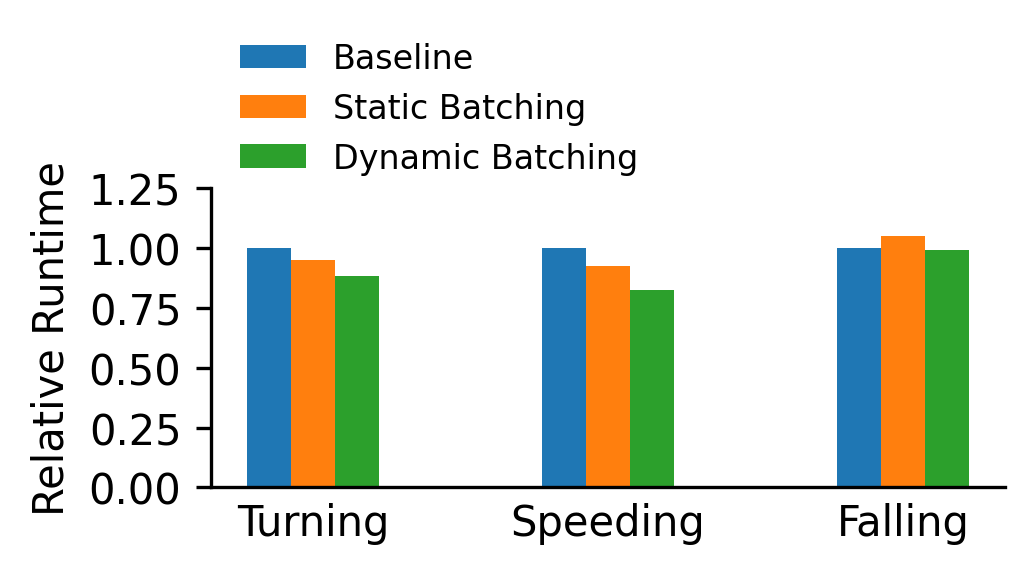

Figure 3 shows the performance comparison with various batching methods. “Static batching” means a padding-based batching, where we use the same batch size across frames. While in “dynamic batching”, the batch is determined by the number of objects of interest in each frame. Note for falling detection, static batching even gives worst performance and dynamic batching shows no performance gain. This is because the rare occurrence of falling event.

Figure 3. Runtime performance comparison with object batching

These two experiments show we can achieve up to 2.89 times performance gain with adaptive filtering, and up to 1.21 times performance gain with dynamic batching.

Future Work

One of the interesting questions we found when designing the language is how to give user a better way to define special properties. Our existing solution based on dynamic binding lets users to specify a external function call or write a snippet of Python code. We are considering a more human-center, whether we can use natural language to describe these properties.

An example is shown below. The second argument to obj.get is a natural language description of this getter method. A smart compiler should this sentence to synthesize the corresponding program. We also need to specify various other language hints, such as type annotations.

class SpeedingTicketQuery(Query):

def __call__(frame: Frame) -> List[str]:

plates = []

for obj in frame.objs:

if obj.cls == "Car" and obj.get("speed", "speed in mile per hour",

stateful=True, typ=float) > 75:

plates.append(obj.get("plate", "license plate of a car", typ=str))

return plates

We found a line of work called natural language specification [7], which is quite to similar to our proposal. We think this may be a potential future work, which will dramatically change software development.

Conclusion

In this work, we designed a new domain-specific language, VQPy, trying to eliminate language limitations of current video analytics applications. We combined the benefits Python and SQL-live languages, by providing a flexible Python-like interface for query specification and build a source-to-source compiler to transparently implement frame filtering and batching techniques. We evaluated these optimizations on various applications and showed a considerable performance improvement.

References

- Rougier, C., Meunier, J., St-Arnaud, A., & Rousseau, J. (2011). Robust video surveillance for fall detection based on human shape deformation. IEEE Transactions on circuits and systems for video Technology, 21(5), 611-622.

- Unattended Baggage Detection Using Deep Neural Networks in Intel® Architecture, https://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/artificial-intelligence/solutions/unattended-baggage-detection-using-deep-neural-networks.html

- Kang, D., Bailis, P., & Zaharia, M. (2018). Blazeit: Optimizing declarative aggregation and limit queries for neural network-based video analytics. arXiv preprint arXiv:1805.01046.

- Kocur, V. (2019). Perspective transformation for accurate detection of 3d bounding boxes of vehicles in traffic surveillance. In Proceedings of the 24th Computer Vision Winter Workshop (Vol. 2, pp. 33-41).

- Li, Y., Padmanabhan, A., Zhao, P., Wang, Y., Xu, G. H., & Netravali, R. (2020, July). Reducto: On-camera filtering for resource-efficient real-time video analytics. In Proceedings of the Annual conference of the ACM Special Interest Group on Data Communication on the applications, technologies, architectures, and protocols for computer communication (pp. 359-376)

- Zha, S., Jiang, Z., Lin, H., & Zhang, Z. (2019). Just-in-Time Dynamic-Batching. arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.07421.

- Campagna, G., Xu, S., Moradshahi, M., Socher, R., & Lam, M. S. (2019, June). Genie: A generator of natural language semantic parsers for virtual assistant commands. In Proceedings of the 40th ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation (pp. 394-410).