Module 2: Unsupervised appraoches for latent space interpretaion of GANs

Since the first GAN model[1] proposed by Ian GoodFellow, there has been a significant improvement in GANs to generate photorealistic images. However the domain of understanding and controlling the images being generated was not widely explored. Recently there are few different appraoches that have surfaced to interpret the image generation in deep generative models. Such approaches can be broadly categorized into supervised and unsupervised approaches. Supervised appraoches have come first and there was lot of analysis done on them. In contrast, this survey focuses on summarizing the very recent works done on unsupervised interpretation of GANs. We will discuss about identifying and editing the human intepretable concepts hidden in the image generation process of GANs. We will briefly discuss the unsupervised methods GANSpace[2], SeFa[3] and LatentCLR[4] to understand the recent works in this domain.

Introduction

Generative Adversarial Networks have been widely succesful in generating varied images. Various GAN architectures like PGGAN[6], StyleGAN[6], BigGAN[7], StyleGAN2[8] have become popular for different kind of tasks. Most of these GANs generate images from random input latent vectors. Every GAN gains understanding of the kind of image to be generated based on the provided random input. So inherently, the input vectors holds the information needed by GAN to generate the corresponding image. It has been found [9,10,11] that when learning to generate images, the GANs represent multiple interpretable attributes in the latent space such as gender for face synthesis, lighting condition for scene synthesis etc. By understanding these interpretable dimensions we can modulate them later to control the image generation process. And also similar techniques can be extended to other deep generative models like VAE.

There exists both supervised and unsupervised interpretaion methods for GANs. Supervised methods focus on generating lots of images and hand labeling them to different categories and then train models to classify latent space. GANDissection[12] is one of the earliest such interpretion method where individual convolutional filters in the network mapped to the segmented objects in the output image are identified and then controlling the object placement by varying the individual units in the network. Later similar supervised interpretaion methods have been developed like InterfaceGAN[13] to edit facial attributes, Steerability of GAN attributes[10] etc. Major concern of supervised approaches involves in annotation of output images to various attribuets. To learn the latent representation of each attribute, the data has to be labeled and trained again. Even though we can learn very accurate latent semantics for various attributes, labeling overhead is critical with supervised approaches. In this paper, we won’t go into the specifics on supervised approaches. Rather we analyse various unsupervised interpretation methods which doesn’t require any labeling. Specifically we focus on three methods GANSpace, Semantic Factorization and LatentCLR. GANSpace is an approach based on Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and data sampling while SeFa takes a closer look at the weight matrix to analyse the latent directions. LatentCLR tried a different approach using contrastive learning to identify diverse interpretable directions of GANs.

GANSpace

The key principles used in this approach includes using Principal Component Analysis to determine important directions in GAN latent spaces for StyleGAN[15], and using feature space for BigGAN[17]. While the mechanisms are fundamental, the controls that they lead to are quite powerful and dictate image attributes ranging from simple properties like pose and shape to subtle attributes like landscape, facial features, and image lighting.

The most basic GAN comprises a probability distribution p(z), from which a latent vector z is sampled, and a neural network G(z) that produces an output image I:z~p(z), I = G(z). The network can be further decomposed into a series of L intermediate layers \(G_1...G_L\). In a StyleGAN model[15, 16], the first layer takes a constant input \(y_0\). Instead, the output is controlled by a non-linear function of z as input to intermediate layers:

\[y_i = G_i(y_{i-1}, w)\]with w = M(z) where M is an 8-layer multilayer perceptron. Normally, the vectors w controlling the synthesis at each layer are all equal; the authors demonstrate that allowing each layer to have its own \(w_i\) enables powerful style mixing.

GANSpace[18] helps us in finding useful directions as the prior distribution p(z) does not indicate the useful directions. Since in the higher dimensions the pixel space is complex this method suggests that for the early layer of GANs the principal components of feature tensors represents important factors of variations. A new image defined by w can be edited by varying PCA coordinates x before it’s feeded to the synthesis network

\[w_0 = w + Vx\]where each entry \(x_k\) of x is a separate control parameter. The entries xk are initially zero until modified by a user.

To compute the principal componenets N random vectors are sampled from Z and their corresponding \(w_i\) is computed using \(w_i = M(z_i)\). The PCA values are then computed from these \(w_1:N\) values which forms the basis V for W and is used to make edits in the image. This technique also provides layerwise control through intermediate latent vectors \(w_i\). For doing the layerwise edits, the modification of \(w_i\) inputs is done only to the range of layers and other layers are left unchanged. For BigGAN[17] as well the image edits are suggested using the similar approach. BigGAN does not have the built-in layerwise control mechanism. But the similar behaviour can be produced by varying the Skip-z inputs \(z_i\) seperately from the latent \(z: y_i = G(y_{i-1}; zi)\)

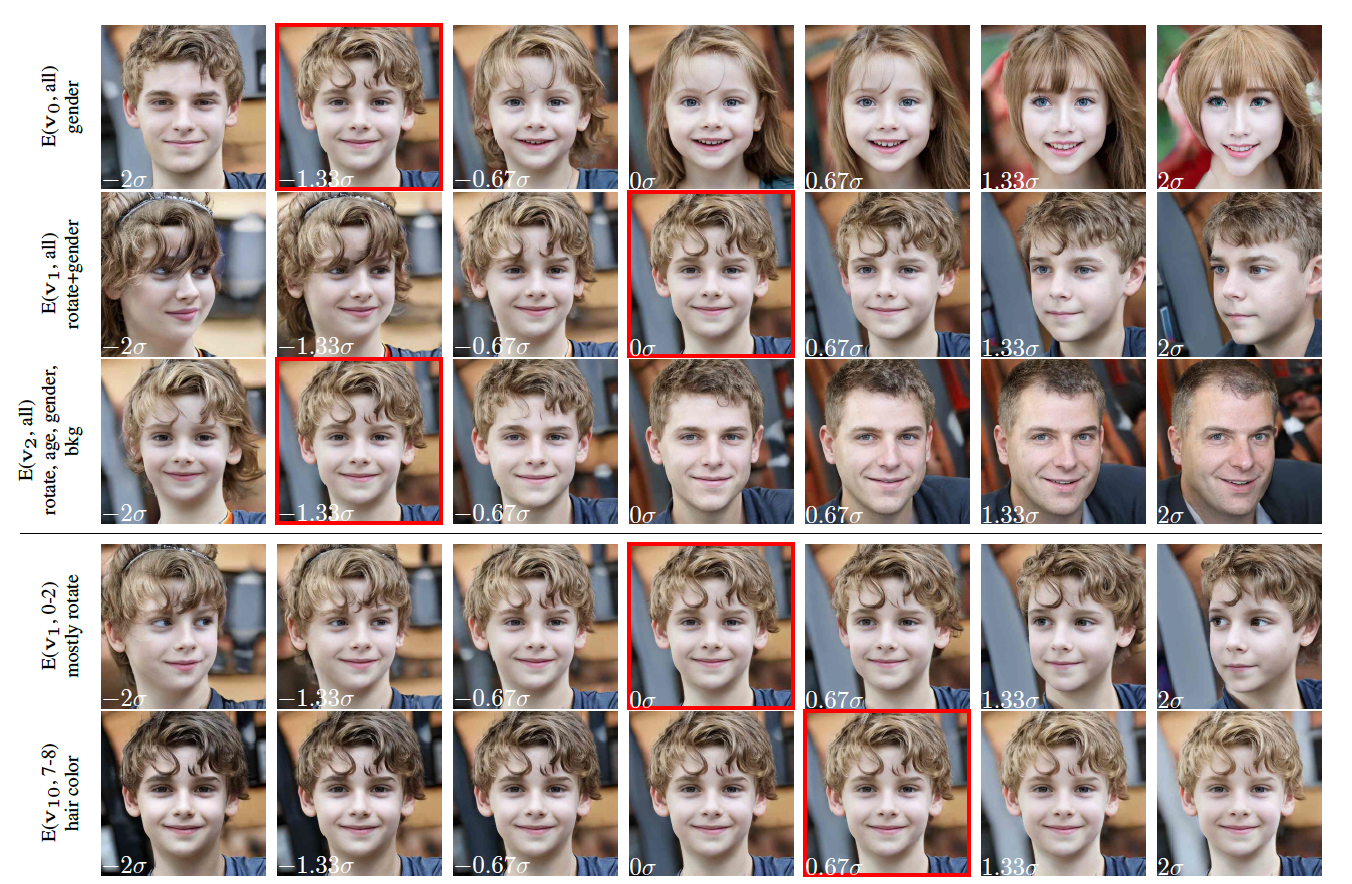

The results obtained using this method is shown below. This method demonstrates simple but powerful ways to create images with existing GANs.

Figure1: GANspace results on StyleGAN2.

Figure1: GANspace results on StyleGAN2.

Semantic Factorization

Semantic Factorization (SeFa) is a closed-form unsupervised method to discover interpretable dimensions in GANs. SeFa method doesn’t involve any training and sampling of latent vectors like the GANSpace method, instead it takes a deeper look into the generation mechanism of GANs to understand the steerable directions in latent space. This method identifies the semantically meaningfully directions in the latent space by efficiently decomposing the model weights. Let G(.) be the generator function of the GAN which maps an input d-dimensional to an RGB image. G(.) consists of multiple layers and each learns a transformation from one to another. Let the first layer’s output of GAN be G1 as shown below:

If we manipulate the input vector along the direction n, the output of first layer (y’) will be updated as below:

From above equation we can observe that manipulation process is instance independent, i.e given any latent vector z and a manipulation direction n, the manipulation effect can be obtained by adding the term to the output of the first layer. From this observation, this model confirms that A contains the essential knowledge of the image variation. As projection of direction vector n onto A results in variations of the image, finding the directions which results in large variations could be the most semantically meaningful directions learned by the GAN. Solving the below optimization problem will result in the top k meaningful directions:

Using above solution, this method shows a beautiful result which says that semantically meaningful directions can be obtained by finding the eigen vectors of the weight matrix A. Thus this method doesn’t need both training and sampling. But we need human intervention to map the directions to corresponding human interpretable dimensions. As discussed before, annotation of discovered dimensions is the main challenge of unsupervised approaches. Also, the dimensions found could include entaglements of multiple interpretable elements and thus might not be useful for editing. Disentaglement of those dimensions is one of gaols of research in this direction.

Figure2: Semantic Factorization method results on StyleGAN and PGGAN.

Figure2: Semantic Factorization method results on StyleGAN and PGGAN.

LatentCLR

Recently there was a new paper which proposes a different unsupervised approach to discover interpretable directions in the latent space of pre-trained GAN models such as StyleGAN2 and BigGAN. They have showed the method finding distinct and fine grained directions on a variety of datasets. This method proposes a contrastive learning-based approach to discover semantic directions in the latent space of pre-trained GANs in a self-supervised manner. Contrastive learning has recently become popular due to leading state-of-the-art results in various unsupervised representation learning tasks. It aims to learn representations by contrasting positive pairs against negative pairs, and learning goal is to move the representations of similar pairs near and dissimilar pairs far. Let us first take a look at SimCLR[13] to understand constrastive loss function. Given a random mini-batch of N samples, SimCLR generates N positive pairs using specified data augmentation method. Let f be the representation of all 2N samples and z be the projections of these samples. The average loss over all positive pairs would be defined as below:

\[h_i = f(x_i) \forall i \\ z_i = g(h_i) \forall i \\ l(x_i,x_j) = -log \frac{exp(sim(z_i,z_j)/\tau)}{\sum_{k=1}^{2N}\mathbf{1}_{[k\neq i]}exp(sim(z_i,z_k)/\tau)} \\ \text{where } \; sim(u,v) = \frac{u^Tv}{\left\| u \right\|\left\| v \right\|} \;\; \text{(cosine similarity)}\]The above loss function constrains the projections of positive pairs to be similar while the projections of negative samples to be dissimilar. This forms the crux of contrastive learning methods. Now let’s see how this is being used to learn the interpretable latent directions in LatentCLR method. Let’s take N sample input latent vectors \((z_1,z_2,...z_N)\). Now we can apply different kinds of direction models like Global, Linear or Non-linear on these input vectors to obtain edited latent vectors \((y_1,y_2,...y_N)\). We can apply the same direction model with changing its internal parameter K times to obtain K edited latent vectors set similar to \((y_1,y_2,...y_N)_k\). The choice of direction model depends on the order of complexity of edit functions we would like to learn (Global being the most simple one). Then for every k, we can compute the feature divergences of N samples as below:

\[f_i^{k} = G_f(z_i^{k}) - G_f(z_i) \\ \text{where } G_f \text{is the feed-forward of GAN upto target layer f.}\]loss function for each edited latent code \(z_i^{k}\):

\[l(z_i^{k}) = -log \frac{\sum_{j=1}^{N} \mathbf{1}_{[j\neq i]} exp(sim(f_i^{k},f_j^{k})) / \tau}{\sum_{j=1}^{N}\sum_{l=1}^{K} \mathbf{1}_{[l\neq k]} exp(sim(f_i^{k},f_j^{l})) / \tau}\]The intuition behind the objective function is that all feature divergences obtained with the same edit operation 1 \(\leq\) k \(\leq\) K, i.e each of \(f_1^{k},f_2^{k},...f_N^{k}\) are considered as positive pairs and contribute to the numerator. All other pairs are considered as negative pairs and contribute to the denominator. With this generalized contrastive loss, the method was able to enforce latent edit operations to have orthogonal effects on the features. In contrast to SeFa, this method additionally can fuse the effects of all selected layers into the target feature layer due to its flexible optimization-based objective.

Figure3: LatentCLR method results on StyleGAN2 and BigGAN.

Figure3: LatentCLR method results on StyleGAN2 and BigGAN.

Comparision

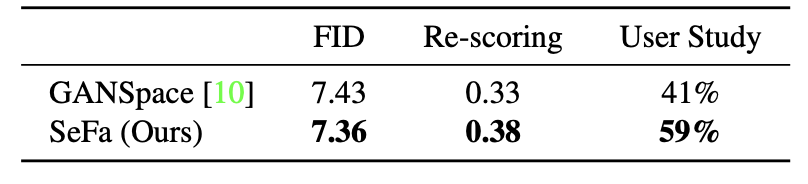

GANSpace is one of the first attempts to do unsupervised learning of interpretable directions on GANs. As GANSpace method includes sampling, the learned latent vector directions only pertain to the scope of sampled images. This is one of the drawbacks of the GANSpace method. SeFa overcomes this by directly analysing the weight matrix. Below are the qualitative and quantitative comparisions between SeFa and GANSpace. It has been identified that SeFa better preserves the identity and skin color of the person in the image while editing.

Figure4: Qualitative comparision between (a) GANSPace and (b) SeFa.

Figure4: Qualitative comparision between (a) GANSPace and (b) SeFa.

Figure5: Quantitative comparision between GANSPace and SeFa(ours).

Figure5: Quantitative comparision between GANSPace and SeFa(ours).

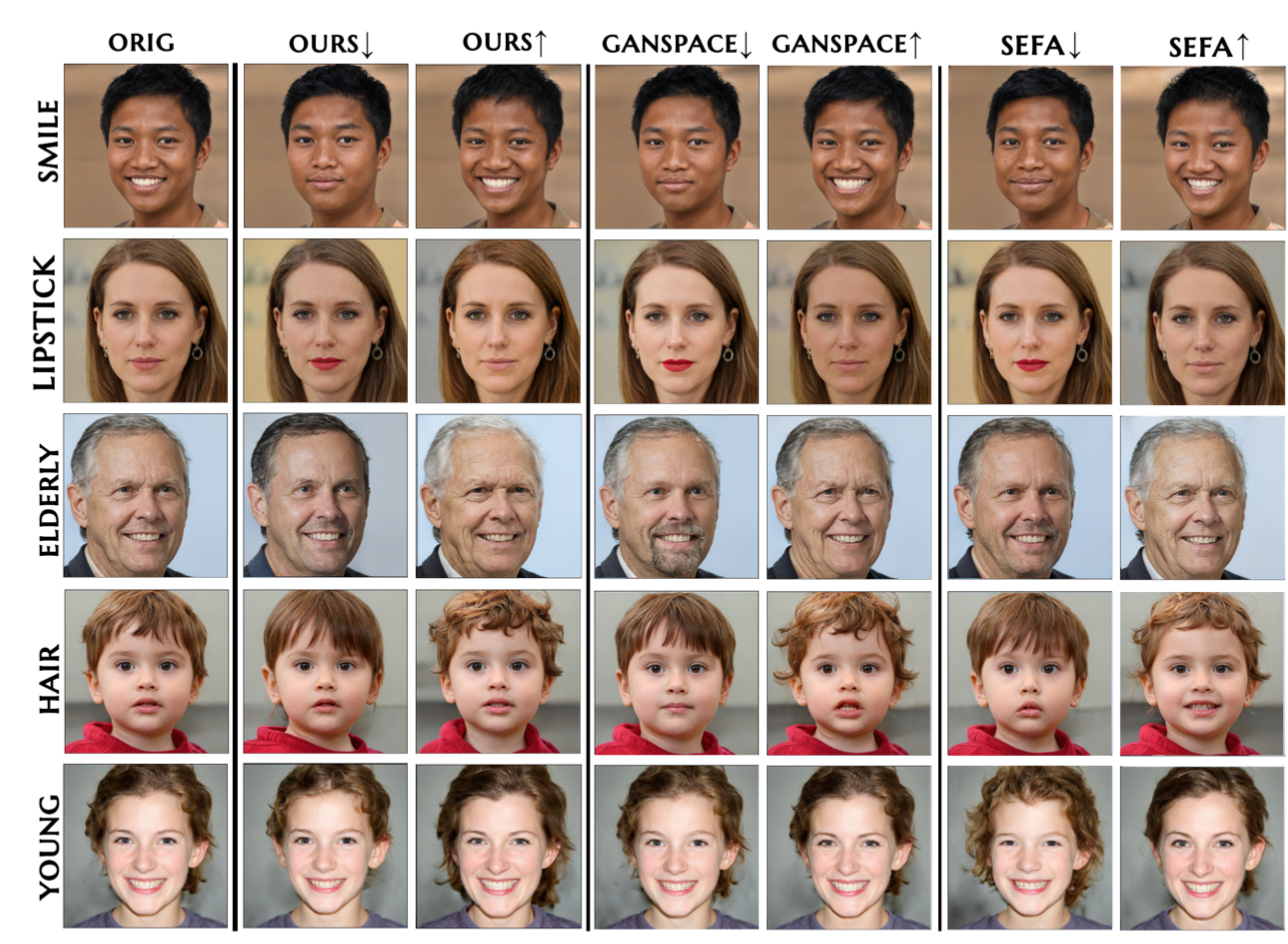

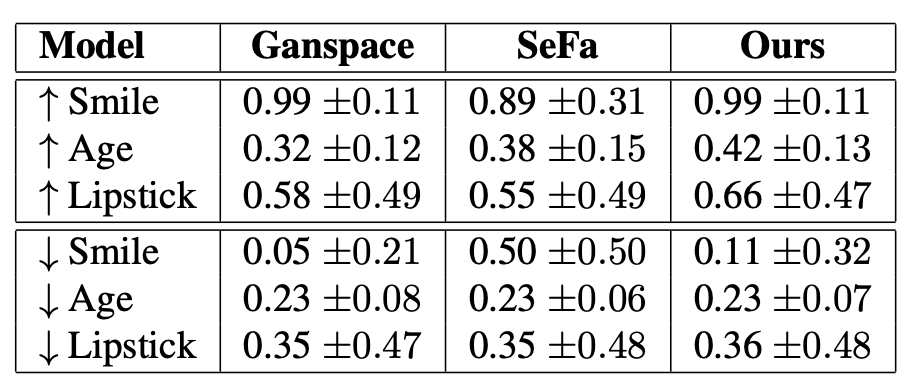

When we compare all the three methods, each method shows its dominance in some of the directions. For example, in below figure we can see that reducing age is better handled by LatentCLR as compared to GANSpace and SeFa. And also, the difference between these methods increase when latent directions are moved in the negative direction but all methods perform similar when moved in the positive directions (compared on Smile, Age and Lipstick). The Quantitative results attached below also confirms the same pattern.

Figure6: Qualitative comparision between LatentCLR(ours), GANSPace and SeFa.

Figure6: Qualitative comparision between LatentCLR(ours), GANSPace and SeFa.

Figure7: Quantitative comparision between LatentCLR(ours), GANSPace and SeFa.

Figure7: Quantitative comparision between LatentCLR(ours), GANSPace and SeFa.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the three methods aim to discover control directions in an unsupervised way for different GAN models. These work suggests considerable future opportunity to analyze these image representations and discover richer control techniques in these spaces. GANspace uses an unsupervised method through PCA to find principal directions in latent space. It relies on taking existing general-purpose image representations and discovers techniques to control them instead of training a new model for each task and successfully creates images using existing GANs. It does not perform any training on images, just takes an existing GAN as input. Closed-Form Factorization technique examines the internal representations learned by GANs and in an unsupervised manner, reveals the underlying variation factors. Various versatile, meaningful semantics can be identified from different types of GAN models using this method which relies on directly decomposing the model weights and , and the performance is comparable to supervised methods. LatentCLR, on the other hand, uses contrastive learning to learn unsupervised directions. Unlike GANspaces and Closed-Form Factorization methods which discover fixed directions, this method can also discover nonlinear directions in pre-trained models and generates multiple distinct, transferrable and semantically meaningful directions. Going ahead, challenges that needs to be addressed by unsupervised methods for GANs interpretation include disentaglement of directions, annotating each discovered dimension and extending to real images using GAN inversion.

Reference

[1] Ian Goodfellow, Jean Pouget-Abadie, Mehdi Mirza, Bing Xu, David Warde-Farley, Sherjil Ozair, Aaron Courville, and Yoshua Bengio. Generative adversarial nets. In Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2014.

[2] Erik Harkonen, Aaron Hertzmann, Jaakko Lehtinen, and Sylvain Paris. Ganspace: Discovering interpretable gan controls. In Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2020.

[3] Yujun Shen, Bolei Zhou. Closed-Form Factorization of Latent Semantics in GANs. Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021

[4] Oğuz Kaan Yüksel, Enis Simsar, Ezgi Gülperi Er, Pinar Yanardag. LatentCLR: A Contrastive Learning Approach for Unsupervised Discovery of Interpretable Directions. ICCV 2021

[5] TeroKarras,TimoAila,SamuliLaine,andJaakkoLehtinen. Progressive growing of GANs for improved quality, stability, and variation. In Int. Conf. Learn. Represent., 2018.

[6] Tero Karras, Samuli Laine, and Timo Aila. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recog., 2019.

[7] Andrew Brock, Jeff Donahue, and Karen Simonyan. Large scale GAN training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. In Int. Conf. Learn. Represent., 2019.

[8] Tero Karras, Samuli Laine, Miika Aittala, Janne Hellsten, Jaakko Lehtinen, and Timo Aila. Analyzing and improving the image quality of stylegan. In IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recog., 2020.

[9] LoreGoetschalckx,AlexAndonian,AudeOliva,andPhillip Isola. Ganalyze: Toward visual definitions of cognitive image properties. In Int. Conf. Comput. Vis., 2019.

[10] Ali Jahanian, Lucy Chai, and Phillip Isola. On the ”steerability” of generative adversarial networks. In Int. Conf. Learn. Represent., 2020.

[11] Yujun Shen, Jinjin Gu, Xiaoou Tang, and Bolei Zhou. Inter- preting the latent space of gans for semantic face editing. In IEEE Conf. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recog., 2020.

[12] Bau, D., Zhu, J.Y., Strobelt, H., Zhou, B., Tenenbaum, J.B., Freeman, W.T., Torralba, A.: Gan dissection: Visualizing and understanding generative adversarial networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (2018)

[13] Shen, Y., Yang, C., Tang, X., Zhou, B.: Interfacegan: Interpreting the disentangled face representation learned by gans. IEEE Trans. on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence (2020)

[14] Ting Chen, Simon Kornblith, Mohammad Norouzi, and Ge- offrey Hinton. A simple framework for contrastive learning of visual representations. In International conference on ma- chine learning, pages 1597–1607. PMLR, 2020.

[15] T. Karras, S. Laine, and T. Aila. A style-based generator architecture for generative adversarial networks. In Proc. CVPR, 2019.

[16] T. Karras, S. Laine, M. Aittala, J. Hellsten, J. Lehtinen, and T. Aila. Analyzing and improving the image quality of StyleGAN. In Proc. CVPR, 2020.

[17] A. Brock, J. Donahue, and K. Simonyan. Large scale GAN training for high fidelity natural image synthesis. In Proc. ICLR, 2019.

[18] Erik H¨ark¨onen, Aaron Hertzmann, Jaakko Lehtinen, and Sylvain Paris. Ganspace: Discovering interpretable gancontrols. In Adv. Neural Inform. Process. Syst., 2020. 2