Module 3 Survey: On the Emergence and Elimination of Biases in Artificial Intelligence

While being applied to a broader and broader range of scenarios, artificial intelligence algorithms can still be less helpful or even potentially harmful in many aspects, like social equity or the reliability of essential services in our society. Therefore, we hereby conduct a broad-ranged survey of existing analyses of such and try to compile the underlying ideas into a systematic understanding of the problem to facilitate future research.

- How AI Biases Emerge from Mis-estimating the correlations of factors.

- Existing Efforts in AI De-biasing

- Essentially addressing the AI Bias problem?

- Reference

How AI Biases Emerge from Mis-estimating the correlations of factors.

In the classical understanding, people use the term “AI bias” to describe two major classes of existing problems: dataset bias and the algorithmic bias (sometimes as the consequence of the former one)

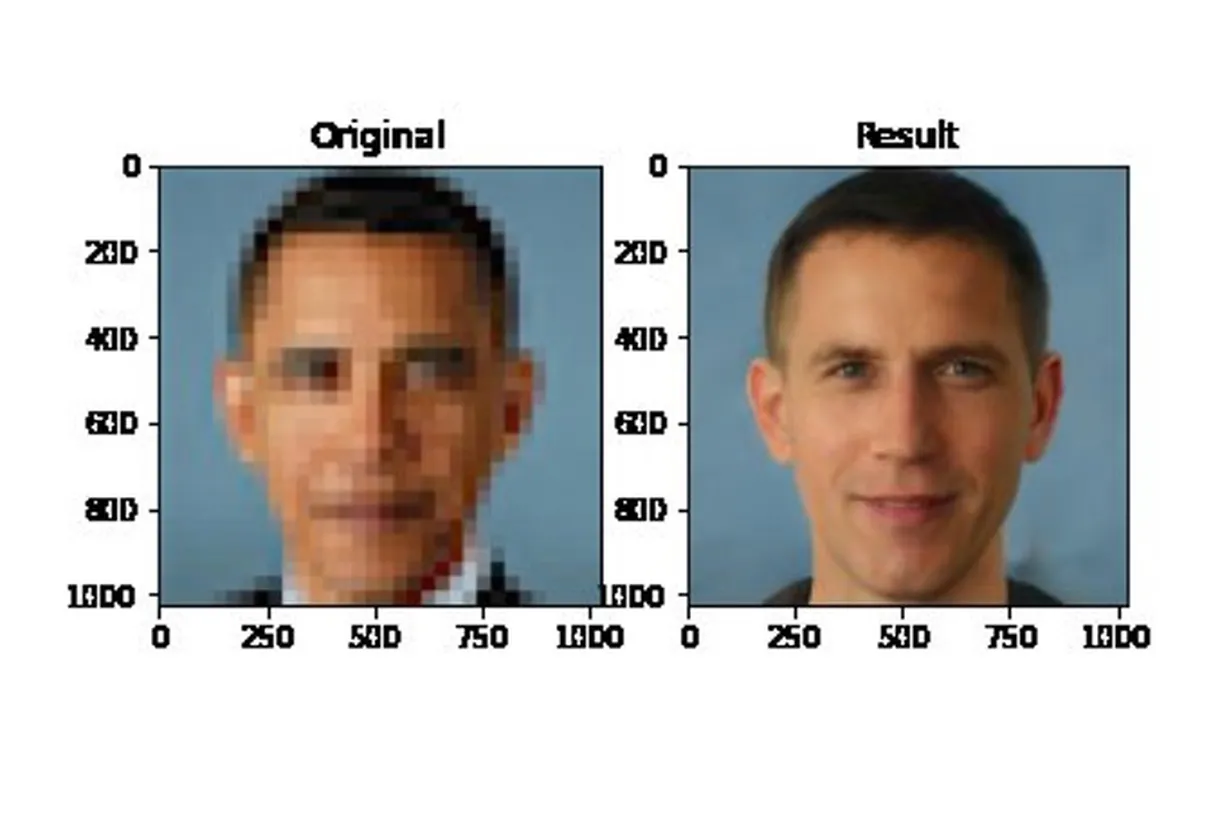

For dataset bias, the most worrisome (and common) case is that the model over-constructs the logical correlations between different factors in the data based purely on the observed co-occurrences. For example, some recent reports show an overly-constructed racial bias in superresolution models [2], indicating a bigger, under-explored problem. See Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Superresolution models overfit Caucasian faces. When applied to African-American people like former President Obama, the model fails to produce the correct/near-correct result but a white man’s face.

Figure 1. Superresolution models overfit Caucasian faces. When applied to African-American people like former President Obama, the model fails to produce the correct/near-correct result but a white man’s face.

While we can tell and probably name some of such overly-constructed correlations, some other important classes of problems are even more hot potatoes: for example, the lack of diversity in how each dataset presents the world. Datasets with such problems hinder effective cross-dataset generalization and introduce irrelevant, anonymous factors that affect models’ compositional generalizability. Four experiments are conducted in the paper unbiased look at data bias[3] to show that diversity within the same label affects model performance.

The authors first verify that:

- 1) different models vary in their abilities to classify different datasets, and

- 2) different computer vision datasets have their own preferences.

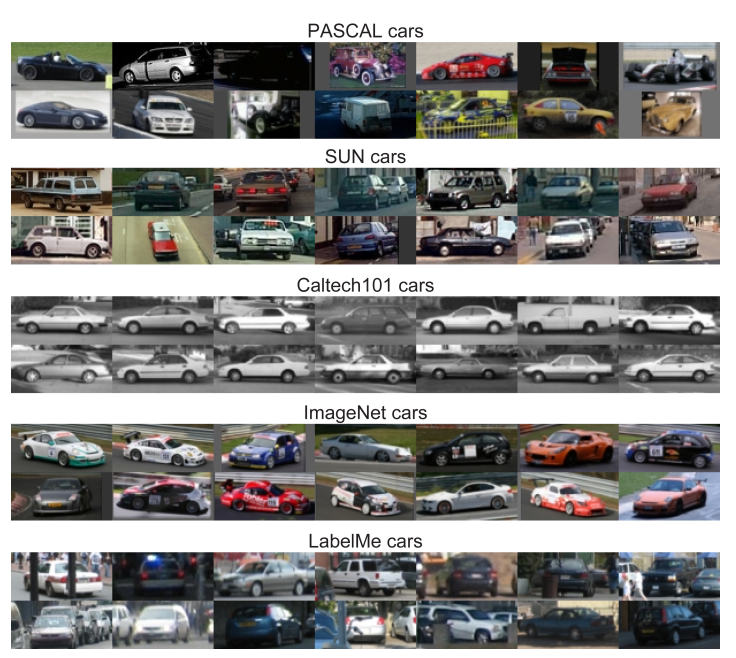

As an example, the authors select “car” images in different datasets and show that the “car” images differ in many aspects, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Images of cars in different datasets vary in poses, colors, resolutions, etc. However, images from the same dataset can still severely lack such diversity.

Figure 2. Images of cars in different datasets vary in poses, colors, resolutions, etc. However, images from the same dataset can still severely lack such diversity.

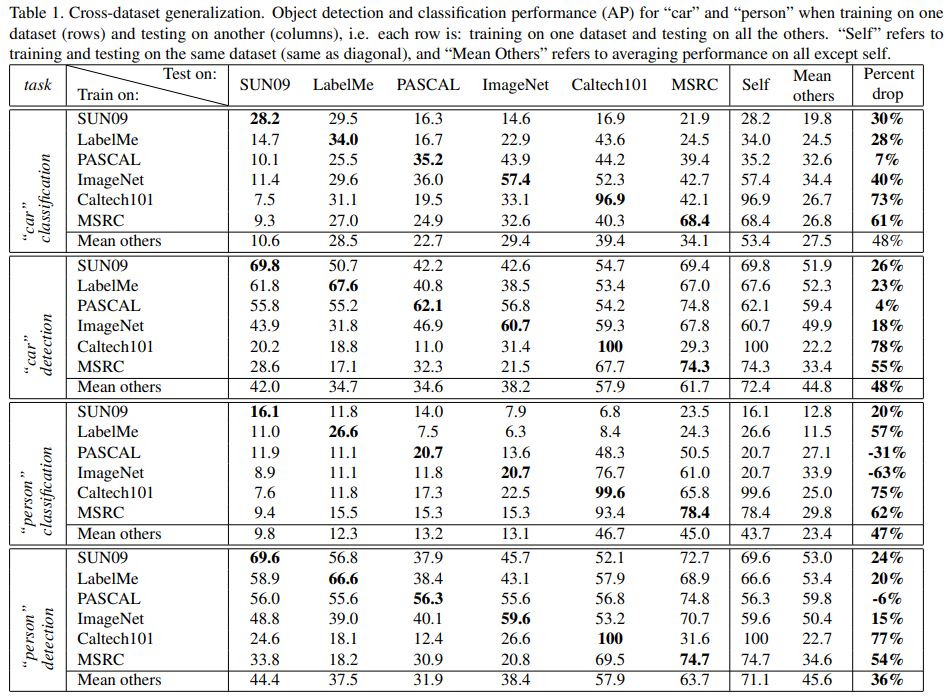

Such differences (and lack of diversity in how the objects are presented) can be easily captured and overfitted by simple machine learning models. To measure the impact of this biased preference on models’ performance in multiple test cases, researchers then train each model on one dataset and test it on other datasets. In particular, they present results for “person” and “car” classification. See Table 1.

The results show that (see Table 1), even if keeping the labels the same but testing models on a different dataset, the model can still suffer from a significant inner-distribution discrepancy and hence degenerate severely in performance. As a comprehensive study, they try to vary negative samples during training/inference and find that whether the negative sample is representative and diverse can also highly affect the model performance. With training data being very different from the inference/validation one, much more data (typically, 5 times more) would be necessary than the vanilla case where the i.i.d. assumption holds well.

In the paper’s conclusion, the authors provide some suggestions for this particular issue. The authors relate the issue to selection bias, capture bias and negative set bias, and provide their proposals of possible solutions:

- Selection bias: the authors suggest obtaining data from multiple sources (multiple countries, multiple search engines) and starting with a large collection of unannotated images. They argue this is better than finding a specific type of image intentionally.

- Capture bias: the authors recommend applying different kinds of augmentations and transformations to reduce model overfitting in one type of environment.

- Negative set bias: the authors recommend adding negatives from different kinds of datasets and mining hard negatives samples if possible.

But still, algorithm-wise, regardless of all these concerns, ever after connectionism methods re-conquered the mainstream of AI, data-driven methods with connectionism philosophy have been producing impressive milestone-level results, refreshing people’s understanding and expectations of which. There is no doubt that data-driven methods do have their merits and are usually the ones with the best practical rationality. Moreover, R.Sutton states his understanding of best practices in methodology in his famous blog post The Bitter Lesson[4].

Figure 3. Imagine how heartbroken the man was when Richard Sutton, the very pioneer and grand master in cybernetics, reinforcement learning and the general field of machine learning, wrote these.

Figure 3. Imagine how heartbroken the man was when Richard Sutton, the very pioneer and grand master in cybernetics, reinforcement learning and the general field of machine learning, wrote these.

In general, while artificially crafted, symbolism-flavored AI systems are appealing in many aspects like explainability and bias control, the history of AI development confirms the supremacy of data-driven, scalable, high-capacity AI models over their seemingly appealing, unscalable kin. This is understandable under necessary assumptions, as such methods try to reflect what the data indicate honestly. When the test cases are similar (or as formally defined as the independent and identically distributed/i.i.d. assumption), such faithful reflection of data directly contributes to model performance. However, without proper inductive bias, the usage of highly data-driven logic is doomed to limit models’ general ability to transfer. Unlike in cases where typical model performance discrepancies come from misconstrued beliefs between almost identical factors, the transferability to new domains sets up a higher standard for models. This is because the actual situation could be testing how belief is well-constructed also for varied group of factors (depending on the relative complexity of the source/target domains).

As part of the results of our compromise between effective practice and well-established theory, AI Bias is a natural, inevitable problem in most data-driven models that we can think of. It is not something we can easily locate within how we design the methodology and eliminate from the root trivially. A better practice would be to admit them and resolve the emerging ones in response.

Existing Efforts in AI De-biasing

Data-level AI De-biasing

Expanding upon our discussion in the previous section, we hereby discuss existing works that try to address and mitigate dataset bias by constructing balanced datasets and incorporating more attributes/features which were historically underrepresented. As a typical one of them:

Gender Shades: Intersectional Accuracy Disparities in Commercial Gender Classification

This work was the first of its kind comprehensive study of the performance of commercially available computer vision models on various intersectional categories in existing datasets and the extent to which a Computer Vision model amplifies bias in an unbalanced dataset. The authors highlight the point that since more and more decisions in various areas like hiring, granting loans, and recidivism scores are handled by AI, it is of paramount importance to accept and expand upon the progress in bias identification and mitigation. This is in alignment with the concerns that we are trying to address in this module survey.

The authors mention that commercially available gender classification models have been provided by various top companies without proper documentation and peer review. Hence there is limited information as to the exact technologies they are using for such models. These models will be used by lots of people as they are commercially available, and trust in these large companies is high. So their study is of great significance. In this regard, they propose a new face dataset which they claim to be balanced based on skin and gender types. They also conduct a thorough analysis of the performance of such models on intersectional categories like light males, light females, dark males and dark females. They use 3 commercially available models for this purpose, which we will discuss in the upcoming sections.

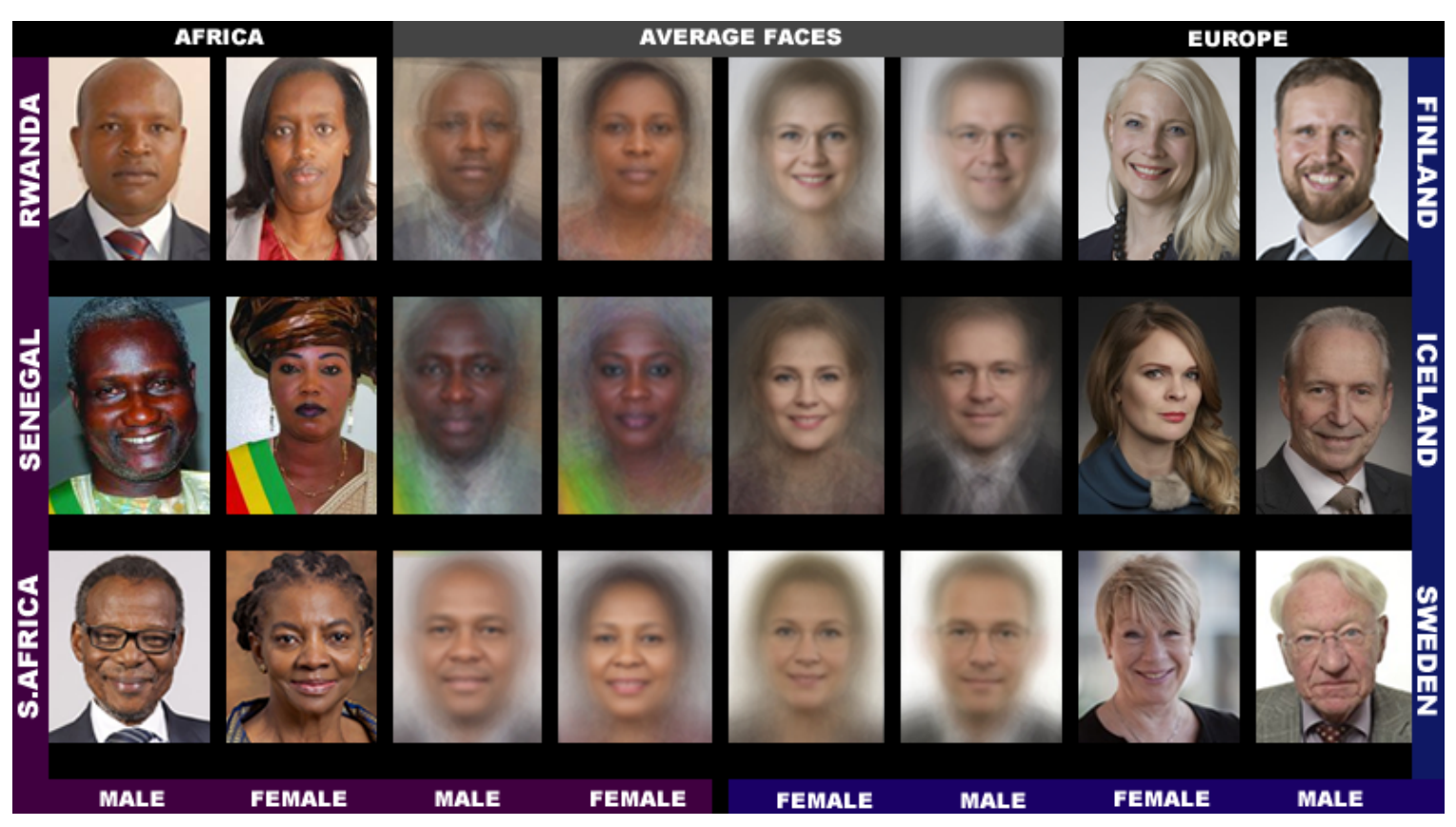

A key component of the paper deals with proposing a new dataset called PPB (Pilot Parliaments Benchmark) and discussing its collection, annotation and processing of balancing. The dataset consists of two gender classification labels (Male/Female) and a 6 point Fitzpatrick labeling system to show skin type. The type of 6 point Fitzpatrick label is determined according to the reaction of a person’s skin to Ultraviolet Radiation (UVR). Dermatologists use this as a standard for skin classification and determining skin cancer risk. They also classify the labels (I - III) as White and (IV-VI) as Black.

Figure 4. The images in PPB are constrained with relatively little variation in pose.

Figure 4. The images in PPB are constrained with relatively little variation in pose.

Coming to statistics of PPB (see Figure 4), it consists of 1270 parliamentarians from 6 countries – 3 African countries (Rwanda, Senegal and South Africa) and 3 European countries (Iceland, Finland and Sweden). It is a highly constrained dataset, i.e. the pose is relatively fixed, illumination is constant, and expressions are neutral or smiling. Coming to labelling, 3 annotators and the authors provided gender and Fitzpatrick skin type labels for PPB Dataset. They also took help from an ABS board-certified surgical dermatologist who provided the definitive labels for the Fitzpatrick skin type. The overall intersectional statistics of the dataset are below (the dataset is balanced across different categories) :

| Demography | n | F | M | Darker | Lighter | DF | DM | LF | LM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Subjects | 1270 | 44.6% | 55.4% | 46.4% | 53.6% | 21.3% | 25.0% | 23.3% | 30.3% |

| Africa | 661 | 43.9% | 56.1% | 86.2% | 13.8% | 39.8% | 46.4% | 4.1% | 9.7% |

| Europe | 609 | 45.5% | 54.5% | 3.1% | 96.9% | 1.3% | 1.8% | 44.2% | 52.7% |

Now coming to commercial gender classification models, the authors pick 3 commercial gender classification models:

- Microsoft’s Cognitive Services Face API

- IBM’s Watson Visual Recognition API

- Face ++

All models lacked technical details and what training data was used, but all of them used some sort of deep learning. The results of the models on the PPB dataset revealed that their overall accuracies were very good, ranging from 88% - 94%. However, all classifiers had a performance gap of 8.1% − 20.6% on male faces over females and a gap of 11.8% − 19.2% on lighter faces over darker faces. Also, all of them performed worst on darker female faces (20.8% - 34.7%). This shows that even though the PPB dataset is balanced, the models had some bias over male and lighter faces and failed significantly on darker females. As a limitation of the work, we would like to highlight that even though the authors claim that the PPB dataset is balanced, it is not balanced over different skin type labels from I - VI. However, the impact of the work was very significant, leading to a lot of different future studies.

Model-level AI De-biasing

A natural thought would be to blame all the things on the problematic data. Some would argue that data could be nothing but a sincere reflection of the world and that the AI bias, at the end of the day, is essentially OUR bias.

Moving beyond the idea of “algorithmic bias is a data problem

While this could be arguably correct in philosophy, in practice, recent discussions gradually led to a more practical conclusion that we need to move beyond the idea of “algorithmic bias is a data problem” due to multiple reasons[5]:

- Machine learning models can and do amplify undesirable biases in aspects like race, gender and geo-diversity, etc. The previous Obama example is exactly one concrete example of such. [5] also lists some related comprehensive study like [12].

- De-biasing the data is costly and hinge on

- Knowing a priori what sensitive features are responsible for the undesirable bias

- Having comprehensive labels for protected attributes and all proxy variables

For the latter, satisfying both are often infeasible. This is primarily due to the high dimensionality and large size of the actual data we deal with (e.g. image, language, even videos, etc.). It is hard to guarantee all features are comprehensively labeled and can hardly be alleviated with even a limited number of attributes.

Even if we could, it would still raise more problems than it resolves. Forbidden labels, like gender/races, can actually be implicitly reconstructed by leveraging proxy variables (those that we use to mask out the bias-introducing factors). This could be worse than just letting the model learn from the original data. Also, inappropriate corruption of the data can lead to noisy and/or incomplete labels.

In practice, we just can’t guarantee zero-bias data. Considering the fact that “The overall harm in a system is a product of the interactions between the data and our model design choices.”, de-biasing at the model level seems an essential solution.

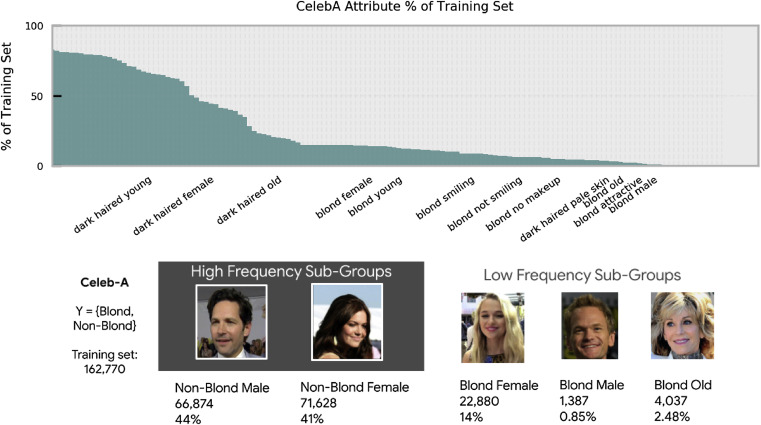

For our audience curious about how the author strengthens his point, the author actually presents it by analyzing a concrete case on the Celeb-A human face dataset (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Datasets like CelebA can be very unbalanced for different subgroups of people. This is essentially causing a large proportion of the AI bias problems.

Figure 5. Datasets like CelebA can be very unbalanced for different subgroups of people. This is essentially causing a large proportion of the AI bias problems.

Detailed explanation can diverge a little bit from this survey paper of ours, thus we won’t be further extend the description here. If you feel very eager about how the author tackles the analysis, we encourage you to refer to the original blog post (which is also a survey paper).

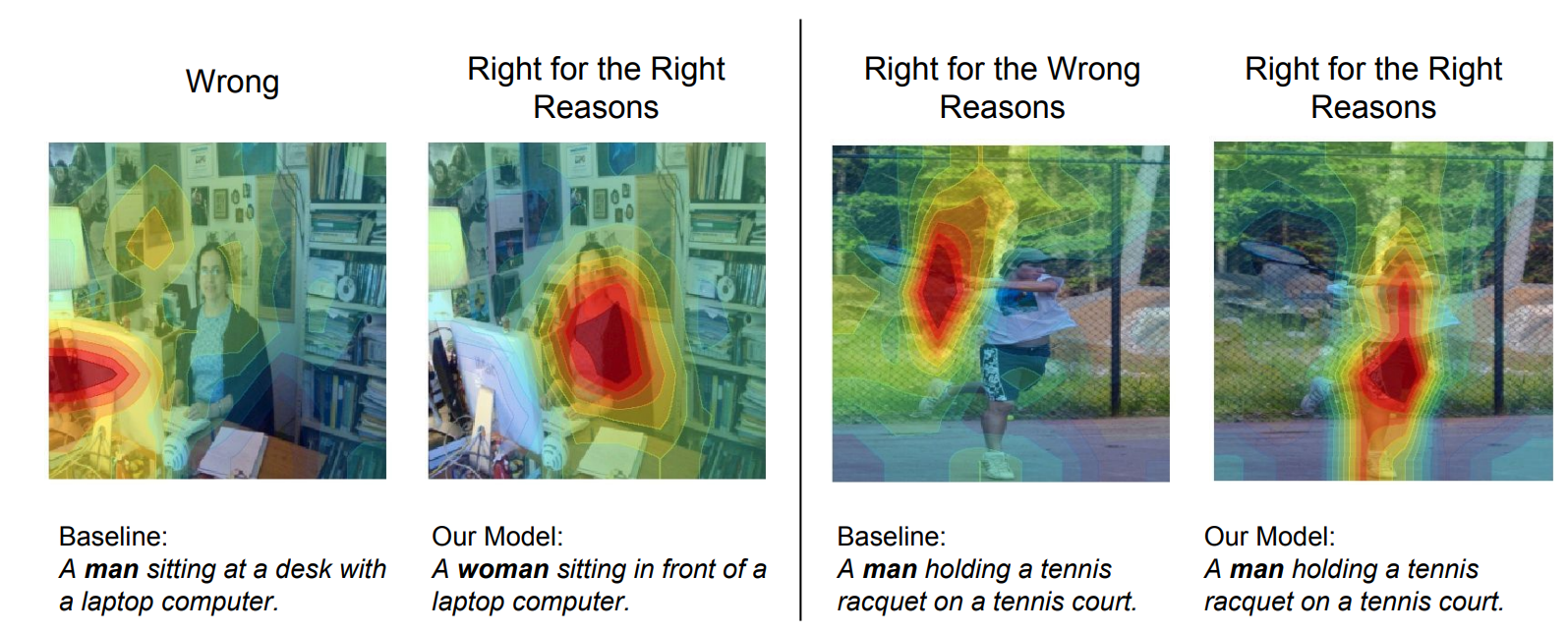

The Equalizer Model: Reduce Bias Amplification in Captioning Models

Some well-founded approaches have been achieved following this way of thinking in the past few years. For example, one work [6] discussed in detail how such de-biasing can be achieved (at least by a large margin) in caption generation models. In this work, the authors proposed a novel Equalizer model that could reduce gender bias in the caption generation model by forcing the model to look at the proper evidence of the target image. The authors believe that the generality of their work allows the model to be expanded to other common protected attributes, such as race and ethnicity, making it a universal approach to overcoming bias in captioning models.

Figure 6. Illustration of the Equalizer model.

Figure 6. Illustration of the Equalizer model.

The key point of the Equalizer model (see Figure 6) is to introduce two complementary loss terms additional to the base loss, which are the Appearance Confusion Loss and the Confident Loss so that they could restrict the model to only focus on the appropriate gender evidence on the target image. Appearance Confusion Loss allows the description model to be confused when the gender evidence of the description target does not appear on the image. Formally, the Appearance Confusion Loss is defined as,

which is the average confusion value (\(\mathcal{C}\)) of the gendered words in one image description, where the confusion of a gendered word is measured by,

\[\mathcal{C} (\tilde{w_t}, I') = | \sum_{ g_w \in \mathcal{G_w} } p( \tilde{w_t} = g_w | w_{0:t-1}, I') - \sum_{ g_m \in \mathcal{G_m} } p( \tilde{w_t} = g_w | w_{0:t-1}, I') |\]Intuitively, given a set of women-gendered words (\(\mathcal{G_w}\)), and a set of men-gendered words (\(\mathcal{G_m}\)), the confusion of a description word is the difference of probability that the word is in a specific group, conditioned on the previous sequence and a mask of the original image which only contains the direct gender evidence. On the other hand, the Confident Loss encourages the model to be confident when gender information is observed. The Confident loss is defined as the average confidence of the predicted gendered words in the description of one image, which is,

\[\mathcal{L}^{Con} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{n=0}^{N} \sum_{t=0}^{T} (\mathbb{1}(w_t \in \mathcal{G_w}) \mathcal{F}^W(\tilde{W_t},I) + \mathbb{1}(w_t \in \mathcal{G_m})\mathcal{F}^W(\tilde{W_t},I) )\], where the confidence (\(\mathcal{F}\)) of a predicted gender word is measured by the quotient between predicted probabilities of the word belonging to each gender group, conditioned on the previous sequence and the input image. For instance, the confidence in the women group is,

\[\mathcal{F}^W (\tilde{w_t},I) = \frac{\sum_{g_m \in \mathcal{G_m} } p( \tilde{w_t} = g_m | w_{0:t-1}, I) }{\sum_{g_w \in \mathcal{G_w} } p( \tilde{w_t} = g_w | w_{0:t-1}, I) + \epsilon}\]The final Equalizer is a linear combination of the the Appearance Confusion Loss(\(\mathcal{L}^{AC}\)), the Confident Loss(\(\mathcal{L}^{Con}\)), and the standard cross-entropy loss(\(\mathcal{L}^{CE}\)). The two complementary loss terms work together to force the description model to focus on the appearance of gender information, other than the unrelated or stereotyped context when producing a gendered description word.

After training and testing on the MS-COCO dataset, the experiment result illustrated the ability of the Equalizer model to reduce outcome divergence between the majority and the minority groups, mitigating the bias amplification issue. Moreover, applying explanation methods to the caption results, it is proved that the equalizer model is able to focus on the gender clue of the individuals from the target image other than the unrelated context when describing their gender. However, this method also comes with drawbacks. Firstly, the authors also mentioned a small drop in performance on standard description metrics, possibly because the regularized model is more conservative, so it uses gender-neutral terms to describe appearance with little gender evidence. Also, proper gender evidence needs to be provided for training images, making applying this method to abstract features harder.

AI De-biasing practices and policies from the Industry

As the importance of AI de-biasing has been brought to the attention of the industry, a group of leaders from the academic disciplines and industry sectors has gathered together to draw upon the insight of identifying and mitigating AI-bias in real-world applications. First of all, it is never enough to emphasize how much harm a biased decision system could do to the minority group. AI decisions must be trustworthy and ethical to ensure that the users of the application could enjoy equal benefits from the system. Different notions of fairness (e.g., equality of odds, demographic parity) have been proposed as metrics to define and measure the fairness of a decision system. However, it is still hard to come up with a comprehensive standard to define an ethical and trustworthy automated decision system. After all, fairness is not merely a mathematical notion or metric. It is more of a shared value and an ethical belief of human beings. Therefore, the authors of [7] proposed a discipline that the developers should consider before they could publish their work for public usage.

Firstly, Operators of algorithms must develop a bias impact statement to guide them through the design, implementation, and application of the AI system. Such a statement contains questions to ask about themselves, which help the developers to better regularize the unfairness in their work. Some template questions could be: identifying the group of users, especially those minority groups who are more liked to experience unfair decisions. What metrics will be used to properly measure the potential unfairness of the system? How to compensate for the harm that the unfair decision could do? Questions should be asked, and actions should be taken for all participants in this system, including the stakeholders, the developers, and all others who will be impacted by the decision.

On the other hand, formal and regular auditing of algorithms to check for bias is another best practice for detecting and mitigating bias. Operators of algorithms must rely upon cross-functional work teams and expertise to review and detect blind spots that could be missed from a single perspective. Lastly, black-box models lack the self-explanation ability to proclaim the validity of their decision. The subjects of automated decisions need better algorithmic literacy, such as the occurrence of bias, to be more actively participating in spotting any potential bias.

In general, mitigating the AI bias on multiple levels has been granted more and more attention. As the solutions stabilize with more developed regularizations, it’s definitely more than just hope to hear from a less unfortunate accident from an unfair automated decision system in the future.

Essentially addressing the AI Bias problem?

Unfortunately, up to now, addressing the AI Bias problem is still beyond the best of our ability. However, more and more studies with a relaxed assumption of training/inference data beyond the classical i.i.d. assumption have been conducted [8,9,10]. While they are no essential solutions, step by step, they still shed light on how we can improve the model robustness towards (harmful) biases, and possibly defend the AI Bias-related consequences as a dynamic solution (rather than a static, ideal, essential solution).

Reference

[1] Redmon, Joseph, et al. “You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2016.

[2] Vincent, James. “What a machine learning tool that turns Obama white can (and can’t) tell us about AI bias.” Retrieved October 28 (2020): 2021.

[3] Torralba, Antonio, and Alexei A. Efros. “Unbiased look at dataset bias.” CVPR 2011. IEEE, 2011.

[4] Sutton R. The bitter lesson[J]. Incomplete Ideas (blog), 2019, 13: 12.

[5] Hooker, Sara. “Moving beyond “algorithmic bias is a data problem”.” Patterns 2.4 (2021): 100241.

[6] Hendricks, Lisa Anne, et al. “Women also snowboard: Overcoming bias in captioning models.” Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV). 2018.

[7] Lee, Nicol Turner, Paul Resnick, and Genie Barton. “Algorithmic bias detection and mitigation: Best practices and policies to reduce consumer harms.” Brookings Institute: Washington, DC, USA (2019).

[8] Mao, Jiayuan, et al. “The neuro-symbolic concept learner: Interpreting scenes, words, and sentences from natural supervision.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1904.12584 (2019).

[9] Johnson, Justin, et al. “Clevr: A diagnostic dataset for compositional language and elementary visual reasoning.” Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2017.

[10] Lu, Sidi, et al. “Neurally-guided structure inference.” International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2019.

[11] Buolamwini, Joy, and Timnit Gebru. “Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification.” Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency. PMLR, 2018.

[12] Barocas, Solon, Moritz Hardt, and Arvind Narayanan. “Fairness in machine learning.” Nips tutorial 1 (2017): 2.